Abstract

Proper transmission of genetic information requires correct assembly and positioning of the mitotic spindle, responsible for driving each set of sister chromatids to the two daughter cells, followed by cytokinesis. In case of altered spindle orientation, the spindle position checkpoint inhibits Tem1-dependent activation of the mitotic exit network (MEN), thus delaying mitotic exit and cytokinesis until errors are corrected. We report a functional analysis of two previously uncharacterized budding yeast proteins, Dma1 and Dma2, 58% identical to each other and homologous to human Chfr and Schizosaccharomyces pombe Dma1, both of which have been previously implicated in mitotic checkpoints. We show that Dma1 and Dma2 are involved in proper spindle positioning, likely regulating septin ring deposition at the bud neck. DMA2 overexpression causes defects in septin ring disassembly at the end of mitosis and in cytokinesis. The latter defects can be rescued by either eliminating the spindle position checkpoint protein Bub2 or overproducing its target, Tem1, both leading to MEN hyperactivation. In addition, dma1Δ dma2Δ cells fail to activate the spindle position checkpoint in response to the lack of dynein, whereas ectopic expression of DMA2 prevents unscheduled mitotic exit of spindle checkpoint mutants treated with microtubule-depolymerizing drugs. Although their primary functions remain to be defined, our data suggest that Dma1 and Dma2 might be required to ensure timely MEN activation in telophase.

INTRODUCTION

Faithful chromosome segregation requires the mitotic spindle to be correctly positioned with respect to the cell division axis. Cytokinesis must take place only after this task is achieved and the two sets of chromosomes are sufficiently far apart. Unscheduled cytokinesis before proper chromosome segregation would, in fact, lead to formation of anucleate and polyploid cells. Eukaryotic cells prevent these harmful events by a surveillance mechanism, called spindle position checkpoint, that delays cytokinesis in the presence of mispositioned or misoriented spindles until errors are corrected. This control is particularly critical for organisms, such yeasts and higher plants, that specify the site of cytokinesis before spindle assembly.

In the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the mitotic spindle first gets positioned close to the bud neck, the constriction where cytokinesis will take place later on, and then crosses the neck to enter the bud, dragging the nucleus along. Spindle positioning and orientation involve a search- and-capture process and occur in two steps, which depend on two partially overlapping pathways (Schuyler and Pellman, 2001). During the first step cytoplasmic microtubules (cMTs) try to find and interact with specific sites on the bud neck cortex. The EB1/Bim1 protein, localized at the plus end of cMTs, is directly involved in searching cortical sites by promoting cMTs dynamicity (Tirnauer et al., 1999). Nuclear positioning also requires the cortical protein Kar9, with which Bim1 interacts (Miller and Rose, 1998; Korinek et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2000); the septin ring, which also specifies the site for cytokinesis (Kusch et al., 2002); the kinesin Kip3 (Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997; DeZwaan et al., 1997); and other proteins required for Kar9 localization, such as actin (Cottingham et al., 1999), the formin Bni1 (Lee et al., 1999), and myosin V (Beach et al., 2000; Yin et al., 2000). During the second step, dynein (Dyn1) and its regulators dynactin and PacI mediate lateral interactions between cMTs and the cortical protein Num1, thus helping the nucleus to be pulled inside the bud (Adames and Cooper, 2000; Heil-Chapdelaine et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2003; Sheeman et al., 2003).

The spindle position checkpoint is well characterized in S. cerevisiae and requires the Bub2 and Bfa1 proteins (Bardin et al., 2000; Bloecher et al., 2000; Pereira et al., 2000), which form a two-component GTPase-activating protein inhibiting the G protein Tem1 (Geymonat et al., 2002), which is in turn required to activate the mitotic exit network (MEN) in telophase (Simanis, 2003). Tem1-dependent activation of the MEN leads to the release from the nucleolus of the Cdc14 protein phosphatase, which is crucial to promote inactivation of cyclinB-dependent CDKs at the end of mitosis (Visintin et al., 1998). Inhibition of such CDKs is an essential prerequisite for spindle disassembly and cytokinesis at the end of the cell cycle and is obtained in budding yeast by both anaphase promoting complex (APC)-mediated proteolysis of their cyclin subunits and accumulation of the CDK inhibitor Sic1 (Zachariae and Nasmyth, 1999). In addition to its role in MEN activation, however, Tem1 also has been implicated in a MEN-independent cytokinetic process, leading to septin ring splitting into an hourglass-shaped structure (Lippincott et al., 2001). The MEN has a similar structural organization to fission yeast septation initiation network (SIN), which is required for cytokinesis but not for mitotic exit (Simanis, 2003). Unlike budding yeast Bub2, its fission yeast homologue Cdc16 performs an essential cell cycle function, and its inactivation leads to unscheduled formation of septa, generating multinucleate cells. In addition, Cdc16, like Bub2, is involved in the spindle checkpoint (Fankhauser et al., 1993).

Several aspects of MEN regulation and its connections with mitotic exit and cytokinesis control are still obscure, and new players in these important processes still await discovery. In this article, we provide the first characterization of the budding yeast open reading frames YHR115c and YNL116w, which we renamed DMA1 and DMA2, based on the homology of their gene products with that of the fission yeast dma1+ gene, which was originally isolated as multicopy suppressor of the temperature-sensitive growth phenotype caused by cdc16 mutations (Murone and Simanis, 1996). Schizosaccharomyces pombe Dma1 is required for SIN inhibition in the presence of spindle damage (Murone and Simanis, 1996; Guertin et al., 2002) and is homologous, like S. cerevisiae Dma1 and Dma2, to human Chfr, which is missing in several cancer cell lines and has been shown to be a component of a stress-induced mitotic checkpoint (Scolnick and Halazonetis, 2000). All these proteins share a forkhead-associated domain and a ring finger motif, the latter being typical of ubiquitin ligase subunits (Joazeiro and Weissman, 2000). We show here that S. cerevisiae Dma1 and Dma2, which seem to be functionally redundant, are involved in proper septin ring positioning and cytokinesis. The simultaneous lack of Dma1 and Dma2 leads to spindle mispositioning and defects in the spindle position checkpoint. Conversely, overexpression of DMA2 causes cytokinetic defects that are partially suppressed by either BUB2 deletion or TEM1 overexpression, consistently with a lack of proper Tem1 activation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, Media, and Reagents

All yeast strains (Table 1) were derivatives of or were backcrossed at least three times to W303 (ade2-1, trp1-1, leu2-3112, his3-11,15, ura3, ssd1). Cells were grown in YEP medium (1% yeast extract, 2% bactopeptone, 50 mg/l adenine) supplemented with 2% glucose (YEPD), 2% raffinose (YEPR), or 2% raffinose and 1% galactose (YEPRG). Unless otherwise stated, α-factor was used at 2 μg/ml, nocodazole at 15 μg/ml, and hydroxyurea at 100 mM. Synchronization experiments were carried out at 25°C, and unless otherwise stated, galactose was added 0.5 h before release from either α-factor or nocodazole.

Table 1.

Strains used in this study

| Name | Relevant genotype |

|---|---|

| ySP324 | MATa, cdc5-2 |

| ySP601 | MATa, leu2::LEU2::tetR-GFP, ura3::URA3::336XtetO |

| ySP939 | MATa, cdc5::CDC5-HA3::URA3 |

| ySP1034 | MATa, his3::HIS3::GAL1-CDC5 |

| ySP1125 | MATa, pds1::PDS1-myc18::LEU2, leu2::LEU2::tetR-GFP, ura3::URA3::336XtetO |

| ySP1152 | MATa, leu2::LEU2::tetR-GFP, ura3::URA3::336XtetO, mad2::TRP1, bub2::HIS3 |

| ySP1241 | MATa, bni1::URA3 |

| ySP1242 | MATa, bim1::URA3 |

| ySP1370 | MATa, swe1::LEU2 |

| ySP1402 | MATa, dyn1::URA3 |

| ySP1569 | MATa, dma1::KITRP1, dma2::KILEU2 |

| ySP1605 | MATa, dma1::KITRP1, dma2::KILEU2, leu2::LEU2::tetR-GFP, ura3::URA3::336XtetO |

| ySP1778 | MATa, spc42::LEU2, his3::3X HIS3-SPC42-GFP |

| ySP1791 | MATa, his3::HIS3-TUB1-GFP |

| ySP1958 | MATa, leu2::LEU2::tetR-GFP, BMH1::336XtetO::URA3 |

| ySP1978 | MATa, mad2::TRP1, leu2::LEU2::tetR-GFP, BMH1::336XtetO::URA3 |

| ySP2402 | MATα, dma1::KITRP1, dma2::KILEU2, bni1::URA3 |

| ySP2403 | MATa, dma1::KITRP1, dma2::KILEU2, dyn1::URA3 |

| ySP2406 | MATa, dma1::KITRP1, dma2::KILEU2, bim1::URA3 |

| ySP2529 | MATa, dma1::KITRP1, dma2::KILEU2, pds1::PDS1-myc18::LEU2, leu2::LEU2::tetR-GFP, ura3::URA3::336XtetO |

| ySP2925 | MATa, dma1::KITRP1, dma2::KILEU2, his3::HIS3-TUB1-GFP |

| ySP2940 | MATa, dma1::KITRP1, dma2::KILEU2, spc42::LEU2, his3::3X HIS3-SPC42-GFP |

| ySP3016 | MATa, ura3::1X URA3::GAL1-DMA2 |

| ySP3018 | MATa, ura3::4X URA3::GAL1-DMA2 |

| ySP3076 | MATa, cla4::kanMX4 |

| ySP3138 | MATa, bub2::HIS3 |

| ySP3174 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), bub2::HIS3 |

| ySP3175 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(m), bub2::HIS3 |

| ySP3318 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(m), cdc5::CDC5-HA3::URA3 |

| ySP3355 | MATa, dma1::KITRP1, dma2::KILEU2, cdc5::CDC5-HA3::URA3 |

| ySP3402 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), mad2::TRP1, leu2::LEU2::tetR-GFP, BMH1::336XtetO::URA3 |

| ySP3413 | MATa, dyn1::URA3, bub2::HIS3 |

| ySP3417 | MATa, tem1::URA3, tem1-3 (on Ycplac111) |

| ySP3423 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(m), his3::HIS3::GAL1-CDC5 |

| ySP3428 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(m), leu2::LEU2::tetR-GFP, BMH1::336XtetO::URA3 |

| ySP3433 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), leu2::LEU2::tetR-GFP, BMH1::336XtetO::URA3 |

| ySP3524 | MATa, cla4::kanMX4, cla4-75 (on Ycplac22) |

| ySP3535 | MATa, lte1::kanMX4 |

| ySP3616 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-TEM1 |

| ySP3656 | MATa, DMA2::GAL1-DMA2(s)::URA3 |

| ySP3657 | MATa, DMA2::GAL1-DMA2(m)::URA3 |

| ySP3721 | MATa, DMA2::GAL1-DMA2(m)::URA3, ura3::URA3::GAL1-TEM1 |

| ySP3748 | MATa, DMA2::GAL1-DMA2(m)::URA3, bub2::HIS3 |

| ySP3779 | MATa, cdc5::kanMX4, trp1::TRP1::cdc5-1-HA3 |

| ySP3833 | MATa, amn1::kanMX4 |

| ySP3962 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(m), amn1::kanMX4 |

| ySP4000 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), cla4::kanMX4, bub2::HIS3 |

| ySP4001 | MATα, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), cla4::kanMX4 |

| ySP4006 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), lte1::kanMX4, bub2::HIS3 |

| ySP4008 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), lte1::kanMX4 |

| ySP4010 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), cdc5::kanMX4, trp1::TRP1::cdc5-1-HA3, bub2::HIS3 |

| ySP4011 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), cdc5::kanMX4, trp1::TRP1::cdc5-1-HA3 |

| ySP4013 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), cdc5-2, bub2::HIS3 |

| ySP4014 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), cdc5-2 |

| ySP4023 | MATa, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(m), swe1::LEU2 |

| ySP4133 | MATα, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), tem1::URA3, tem1-3 (on Ycplac111) |

| ySP4154 | MATα, dma1::KITRP1, dma2::KILEU2, cla4::kanMX4, cla4-75 (on Ycplac22) |

| ySP4155 | MATa, dma1::KITRP1, dma2::KILEU2, cla4::kanMX4, cla4-75 (on Ycplac22) |

| ySP4156 | MATα, ura3::URA3::GAL1-DMA2(s), tem1::URA3, tem1-3 (on Ycplac111), bub2::HIS3 |

Plasmid Constructions and Genetic Manipulations

Standard techniques were used for genetic manipulations (Sherman, 1991; Maniatis et al., 1992). To clone DMA2 under the GAL1–10 promoter (plasmid pSP185), a XbaI PCR product containing the DMA2 coding region was cloned in the XbaI site of a GAL1–10-bearing YIplac211 vector. pSP185 integration was directed either to the URA3 locus by EcoRV digestion (strains ySP3016 and ySP3018) or to the DMA2 locus by HpaI digestion (strains ySP3656 and ySP3657). Copy number of the integrated plasmid was verified by Southern blot analysis. Because this analysis did not allow to assess the precise number of integrated plasmids for all the transformants, we generically indicated as multiple integrants the strains with an integrated plasmid copy number higher than three (ySP3018 and ySP3657). All strains carrying multiple copies of the GAL1-DMA2 construct (GAL1-DMA2 m) at either the URA3 or DMA2 locus are meiotic segregants derived from the parental strains ySP3018 or ySP3657, respectively, and therefore carry the same number of pSP185 integrated copies as the corresponding parental strain. Gene deletions were generated by one-step gene replacement (Wach et al., 1994).

Protein Extracts, Western Blot Analysis, and Kinase Assays

For Western blot analysis, protein extracts were prepared according to Surana et al. (1993). For Clb2/Cdk1 kinase assays, protein extracts were prepared as described previously (Schwob et al., 1994), and 50 μg of extract was used for measuring kinase activity on histone H1 (Surana et al., 1993) and for Western blot analysis. Proteins transferred to Protran membranes (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) were probed with 12CA5 monoclonal antibodies for hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged Cdc5, and with polyclonal antibodies against Swi6, Clb2, and Sic1 (kind gifts from K. Nasmyth (Institute of Molecular Pathology, Vienna, Austria), W. Zachariae (Max Planck Institute & Molecular Cell Biology, Dresden, Germany), and Mike Tyers (University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada), respectively). Secondary antibodies were from Amersham Biosciences (Piscataway, NJ), and proteins were detected by an enhanced chemiluminescence system according to the manufacturer.

Fluorescence Microscopy, Image Analysis, and Measurements

Nuclear division was scored with a fluorescent microscope on cells stained with propidium iodide. In situ immunofluorescence of microtubules was performed according to Fraschini et al. (1999) by using the YOL34 monoclonal antibody (Serotec, Oxford, United Kingdom) followed by indirect immunofluorescence with rhodamine-conjugated anti-rat antibody (1:100; Pierce Chemical, Rockford, IL). Detection of Cdc3-green fluorescent protein (GFP), Spc42-GFP, and tetR-GFP dots to score sister chromatid separation was carried out on ethanol-fixed cells, upon wash with water and sonication. Digital images were taken with a Leica DC350F charge-coupled device camera mounted on a Nikon Eclipse 600 and controlled by the Leica FW4000 software. To measure distance between spindle and bud neck, sets of three to four fluorescent images in Z-focal planes 0.3 μm apart were combined into single two-dimensional projection. Distances were measured between the proximal end of either metaphase spindles or spindle poles (on Spc42-GFP–expressing cells) and the bud neck on 100–200 cells by using the Leica FW4000 software. Comparisons of statistical significance were done by Student's t-test.

Other Techniques

Flow cytometric DNA quantitation was determined according to Fraschini et al. (1999) on a BD Biosciences FACScan. Percentage of cells with 2C DNA contents was measured with the CELLQuest software.

RESULTS

Lack of Dma1 and Dma2 Affects Spindle Positioning

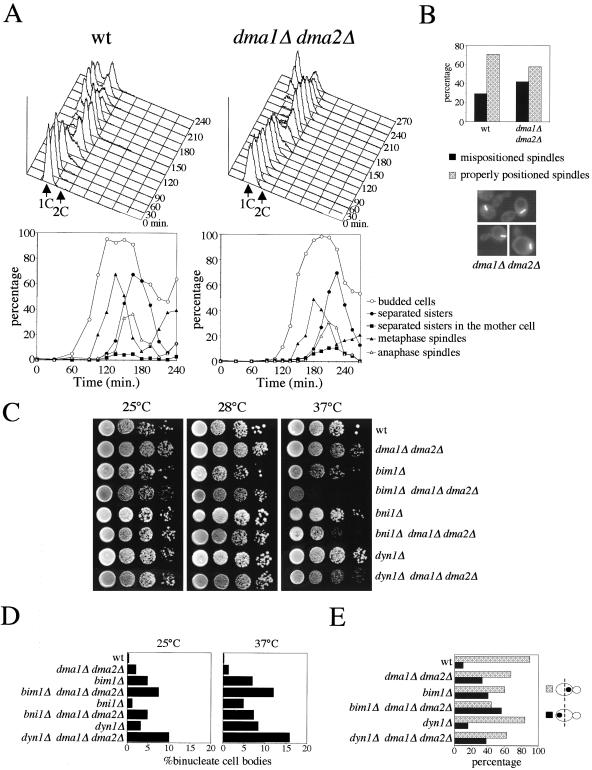

Two homologues of human Chfr, which we renamed Dma1 and Dma2, are found to be encoded by the S. cerevisiae uncharacterized open reading frames YHR115c and YNL116w, respectively. They show 58% of amino acid identity with each other and >40% with S. pombe Dma1, whereas homology with Chfr is less extensive but still significant. To functionally characterize Dma1 and Dma2, we first deleted each single open reading frame and found no detectable effects of the single deletions on either cell cycle progression, cell viability, or spindle checkpoint response (our unpublished data). Because these results, together with the high degree of homology between the two gene products, suggested a possible functional redundancy, we constructed a double dma1Δ dma2Δ strain, which turned out to be viable and therefore suitable for further analysis. To investigate the role of Dma1 and Dma2 in the yeast cell cycle, we then deleted both genes in a haploid yeast strain carrying the tetO/tetR-GFP constructs to monitor sister chromatid separation at arms of chromosome V (Michaelis et al., 1997). Small unbudded cells were purified by elutriation and released into fresh medium at 25°C to monitor at different time points the kinetics of budding, DNA replication, bipolar spindle assembly and elongation, and sister chromatid separation. Despite that we did not find major differences in any of these parameters between dma1Δ dma2Δ cells and wild type (Figure 1A), we noticed that two GFP-separated dots, indicative of chromosome V sister separation, could be found within the same cell body in a higher fraction of dma1Δ dma2Δ cells than wild type (Figure 1A). This suggests that the lack of Dma1 and Dma2 might affect, among other processes, spindle positioning, because the presence of mispositioned spindles does not prevent the onset of anaphase in budding yeast (Sullivan and Huffaker, 1992). Accordingly, when we measured directly the average distance between bud necks and the proximal end of metaphase spindles at the time of their highest percentage (135′ for wild-type and 180′ for dma1Δ dma2Δ cells), we found a slight but statistically significant increase in the value found for dma1Δ dma2Δ spindles (1.35 ± 0.39 vs. 1.14 ± 0.36 μm, p < 0.0001). To confirm that lack of Dma1 and Dma2 affects spindle positioning, we also measured the average distance between the bud neck and the proximal spindle pole body (SPB), as well as the average angle between the short bipolar spindle and the mother-bud axis, in either cycling wild-type or dma1Δ dma2Δ cells expressing the structural SPB component Spc42 fused to GFP and displaying two GFP dots facing each other in the same cell body, indicative of a preanaphase stage. Again, the average distance between the proximal SPB and the bud neck was higher in dma1Δ dma2Δ than in wild-type cells (0.8 ± 0.39 vs. 0.65 ± 0.37 μm, p = 0.004), whereas the mean angle seemed to be not significantly affected (38.6 ± 24.1 vs. 35.6 ± 22.7°, p = 0.3). When we compared spindle orientation in dma1Δ dma2Δ versus wild-type cells expressing α tubulin fused to GFP (Tub1-GFP), we found that indeed the lack of Dma1 and Dma2 caused a slight increase (13%) in the percentage of cells that displayed short bipolar spindles pointing away from the bud neck (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Dma1 and Dma2 are required for proper spindle positioning. (A) Small unbudded wild-type (ySP1125) and dma1Δ dma2Δ cells (ySP2529) were purified by elutriation and allowed to progress in the cell cycle in fresh YEPD medium at 25°C (time 0). At the indicated time points cell samples were collected for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of DNA contents (top) and to score microscopically kinetics of budding, sister chromatid separation, bipolar spindle assembly, and elongation (bottom). (B) Percentage of correctly positioned and mispositioned short metaphase spindles was scored in logarithmically growing cell cultures of wild-type and dma1Δ dma2Δ strains expressing a TUB1-GFP fusion (n ≥ 200). The photograph shows examples of short metaphase spindles in dma1Δ dma2Δ cells. (C) Serial dilutions of strains with the indicated genotypes were spotted on YEPD plates and incubated for2dat either 25 or 37°C. (D) Logarithmically growing cultures of strains with the indicated genotypes were shifted from 25 to 37°C for 4 h. The percentage of binucleate cell bodies over total number of cells was scored after sonication and nuclear staining with propidium iodide (n ≥ 500). (E) The uninucleate budded cells grown at 25°C from D) were scored for nuclear position with respect to the middle (dotted line) of the mother cell (n ≥ 200).

Wild-type cells treated with hydroxyurea (HU) display penetration of the nucleus into the bud, whereas the spindle is confined in the mother cell. This process is defective when spindle positioning is compromised (Yeh et al., 1995). We therefore asked what was the behavior of dma1Δ dma2Δ cells in these conditions and found that, whereas in HU a significant fraction of wild-type cells (39.5%) displayed stretched nuclei across the neck, only 11.8% of dma1Δ dma2Δ cells did so (Table 2), suggesting that proper spindle positioning requires Dma1 and/or Dma2. Conversely, spindle alignment along the mother-bud axis was similar in HU-treated wild-type and dma1Δ dma2Δ cells (mean angle 39.9 ± 25.4° for wild type and 39.9 ± 25° for dma1Δ dma2Δ).

Table 2.

Nuclear distribution in HU-arrested cells

The position of the nucleus relative to the bud and neck was determined on propidium iodide-stained cells. n, cells scored.

We therefore looked for synthetic effects between the double DMA1/DMA2 deletion and mutations in genes implicated in nuclear positioning and/or spindle orientation, such as kip1Δ, kip3Δ, kar3Δ, bim1Δ, kar9Δ, dyn1Δ, bni1Δ, and cla4Δ. The dma1Δ dma2Δ cla4Δ combination turned out to be lethal at 25°C (see below), whereas dma1Δ dma2Δ bim1Δ, dma1Δ dma2Δ bni1Δ, and dma1Δ dma2Δ dyn1Δ strains were temperature sensitive for growth at 37°C (Figure 1C), although to different extents. No obvious synthetic growth defects were found by combining dma1Δ dma2Δ with the remaining tested mutations (our unpublished data). We then asked whether the observed synthetic growth defects correlated with additive effects caused by the above-mentioned mutations on spindle positioning. For this purpose, we measured the percentage of binucleate cell bodies, arising from anaphase taking place in the mother cell, in strains lacking Bim1, Bni1, or Dyn1 either alone or in combination with dma1Δ dma2Δ. As shown in Figure 1D, the absence of Dma1 and Dma2 caused by itself a modest increase in the percentage of binucleate cell bodies, which was additive with that caused by deletion of BIM1, BNI1, or DYN1. The increment in the fraction of binucleate cell bodies in the triple mutants compared with the single mutants was already apparent at 25°C and became more evident after incubation for 4 h at 37°C, due to the stronger effect of BIM1, BNI1, and DYN1 deletions on spindle positioning at this temperature (Figure 1D). Finally, we analyzed nuclear positioning in some of the above-mentioned mutants grown at 25°C, by measuring the amount of budded cells where the nucleus was away from the bud neck with respect to those where the nucleus was correctly positioned. We excluded from this analysis bni1Δ mutants because of their marked clumpiness, which made very difficult to establish the position of the bud necks. DMA1/DMA2 deletion increased by itself the amount of cells with mispositioned nuclei by more than threefold compared with wild type, and slightly increased nuclear positioning defects of bim1Δ and dyn1Δ mutants (Figure 1E). Together, these data suggest that Dma1 and Dma2 participate to spindle positioning.

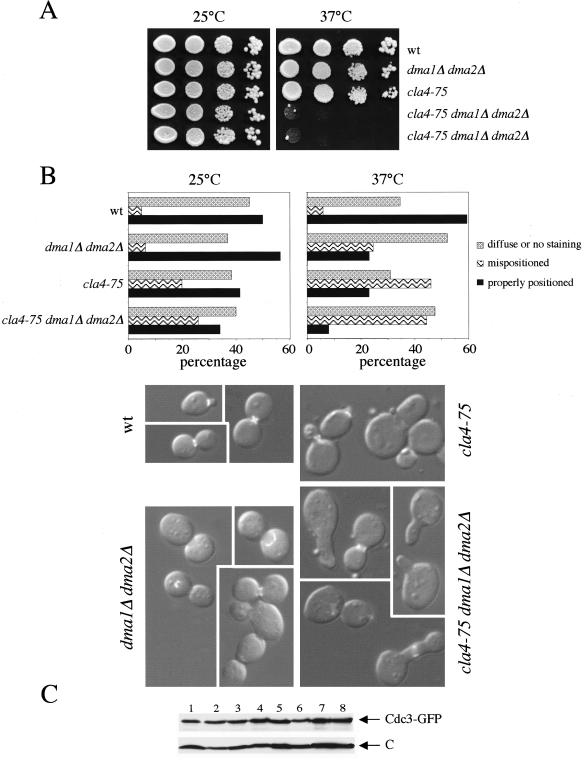

Dma1 and Dma2 Are Required for Correct Septin Ring Assembly

The synthetic lethality caused by the simultaneous lack of Cla4, Dma1, and Dma2 suggested that these proteins might be involved in the same process and prompted us to test whether Dma1 and Dma2 could be involved in septin ring deposition. In fact, the Cla4 PAK kinase has been implicated in the correct assembly of the septin ring at the bud neck at the onset of budding (Cvrckova et al., 1995) and the septin ring is in turn required for correct nuclear positioning (Kusch et al., 2002). By using the temperature-sensitive cla4-75 allele (Cvrckova et al., 1995), we first constructed a cla4-75 dma1Δ dma2Δ triple mutant, which was viable at 25°C but could not grow at 37°C, whereas cla4-75 cells grew normally at 37°C (Figure 2A) due to the functional redundancy between Cla4 and the PAK kinase Ste20 (Cvrckova et al., 1995). Cultures of wild-type, dma1Δ dma2Δ, cla4-75, and cla4-75 dma1Δ dma2Δ cells, all expressing the septin ring component Cdc3 fused to GFP (Cdc3-GFP), were grown at 25°C and then shifted to 37°C for 3 h. As shown in Figure 2B, upon temperature shift the lack of either Cla4 or Dma1 and Dma2 reduced the percentage of cells with a correctly assembled septin ring from 60 to 23 and 32% respectively, whereas it markedly increased the fraction of cells with either mislocalized rings or diffuse unlocalized GFP signal, despite that Cdc3-GFP protein levels remained unchanged (Figure 2C). Strikingly, the simultaneous lack of all the above-mentioned proteins dramatically compromised septin ring deposition, allowing this process to take place correctly in only 8% of the cells. In addition, cla4-75 dma1Δ dma2Δ cells were often misshapen or with wide bud necks (Figure 2B) and mostly arrested with 2C DNA contents and undivided nuclei (our unpublished data), suggesting that the morphogenesis checkpoint might be active in these conditions (Lew and Reed, 1995). Thus, Dma1 and Dma2 participate, like Cla4, to proper septin ring deposition.

Figure 2.

Synthetic effects between dma1Δ dma2Δ and cla4-75 on cell growth and septin ring deposition. (A) Serial dilutions of logarithmically growing cultures of strains with the indicated genotypes were spotted on YEPD plates and incubated for2dat25and37°C. Two independent cla4-75 dma1Δ dma2Δ meiotic segregants from the same heterozygous diploid are shown. (B) Cultures of the indicated strains, all carrying a CDC3-GFP–bearing low copy number plasmid, were grown in selective medium to maintain the plasmid at 25°C and then shifted to 37°C for 3 h. The percentage of cells with either correctly deposited or mispositioned septin ring, as well as diffuse unlocalized signal, was scored by monitoring the septin ring marker Cdc3-GFP (graph, n ≥ 300). The photographs show examples of Cdc3-GFP localization at 37°C in wild-type (wt), dma1Δ dma2Δ, cla4-75, and cla4-75 dma1Δ dma2Δ cells. (C) Same amounts of protein extracts from the cell cultures used for B were analyzed by Western blot with anti-GFP antibodies to monitor protein levels of Cdc3-GFP. 1, wt 25°C; 2, wt 37°C; 3, dma1Δ dma2Δ 25°C; 4, dma1Δ dma2Δ 37°C; 5, cla4-75 25°C; 6, cla4-75 37°C; 7, cla4-75 dma1Δ dma2Δ 25°C; and 8, cla4-75 dma1Δ dma2Δ 37°C. C, loading control.

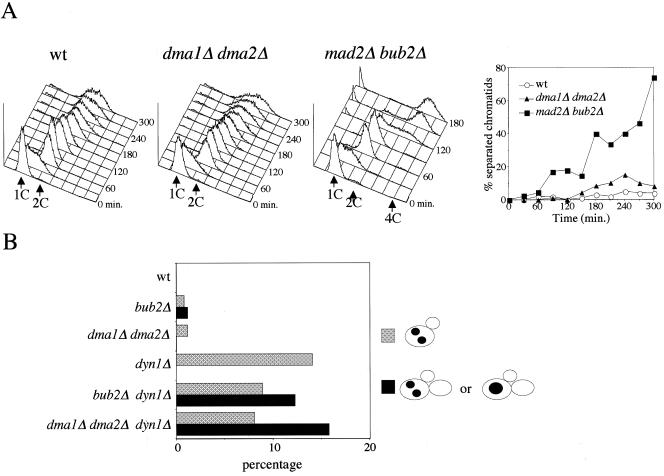

Dma1 and Dma2 Participate to the Spindle Position Checkpoint

Both S. pombe Dma1 and human Chfr have been shown to be involved in mitotic checkpoint responses (Murone and Simanis, 1996; (Scolnick and Halazonetis, 2000). To verify whether Dma1 and Dma2 could themselves function in the spindle assembly checkpoint, we arrested in G1 by α factor and released in the presence of nocodazole dma1Δ dma2Δ cells, as well as wild-type and mad2Δ bub2Δ double mutant cells, all carrying the tetO/tetR-GFP constructs to monitor sister chromatid separation at arm regions of chromosome V (Michaelis et al., 1997). Whereas mad2Δ bub2Δ cells separated sister chromatids and rereplicated their genome very efficiently, being completely checkpoint deficient (Alexandru et al., 1999; Fesquet et al., 1999; Fraschini et al., 1999), wild-type and dma1Δ dma2Δ mutant cells arrested mostly in metaphase with 2C DNA contents (Figure 3A), suggesting that Dma1 and Dma2 are not required for the checkpoint activated by spindle disassembly.

Figure 3.

Dma1 and Dma2 are involved in the spindle position checkpoint. (A) Isogenic strains with the indicated genotypes, all carrying the tetO/tetR-GFP constructs, were arrested in G1 by α factor and released in the presence of nocodazole to measure at different time points DNA contents by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis (left) and sister chromatid separation at arms of chromosome V (right). (B) Cultures of strains with the indicated genotypes were grown at 25°C and shifted at time 0–37°C for 7 h. Percentages of the different cell types, drawn on the right side of the figure, were determined after sonication and nuclear staining with propidium iodide.

We then asked whether Dma1 and Dma2 could instead be involved, like Bub2 and Bfa1, in the spindle orientation checkpoint, that delays MEN activation in response to spindle mispositioning. To address this question, we deleted DMA1 and DMA2 in a strain lacking the dynein-encoding gene DYN1. In the absence of dynein spindles are mispositioned, and as a consequence, a small fraction of cells undergo anaphase and nuclear division in the mother cell (Yeh et al., 1995). In spite of that, cells fail to exit mitosis and divide, due to a Bub2/Bfa1-dependent checkpoint (Figure 3B; Bardin et al., 2000). Because dyn1Δ mutants accumulated binucleate cell bodies at 37°C (Figure 1D) and the dma1Δ dma2Δ dyn1Δ triple mutant was temperature sensitive (Figure 1C), we scored failures in the spindle position checkpoint after 7 h at 37°C, by monitoring the percentage of cells with more than one bud, which had either one undivided nucleus or two separated nuclei within the same cell body and therefore had not undergone a proper anaphase. In fact, the emergence of a second bud in such cells is a marker of unscheduled mitotic exit, no longer coupled to nuclear division. Under these conditions, 14% of dyn1 cells underwent anaphase in the mother cell due to spindle misorientation, but neither rebudded (Figure 3B) nor rereplicated DNA (our unpublished data). Similarly to BUB2 deletion, the lack of Dma1 and Dma2 caused 16% of dyn1 cells to bud again before proper nuclear division (Figure 3B) and to enter a new round of DNA replication, accumulating with DNA contents higher than 2C (our unpublished data), suggesting that these proteins are required to delay mitotic exit in the presence of mispositioned spindles.

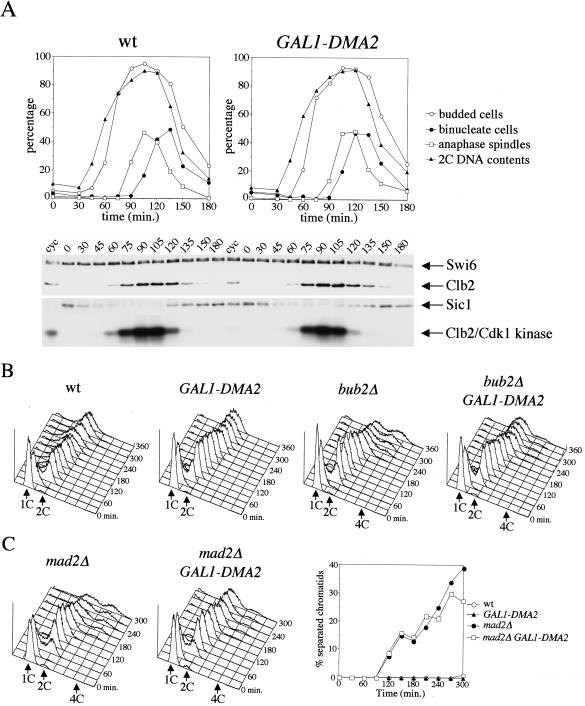

DMA2 Overexpression Prevents Mitotic Exit in Nocodazole-treated bub2Δ and mad2Δ Cells

Because S. pombe dma1+ was isolated as multicopy suppressor of the temperature sensitivity of cdc16 mutant cells (Murone and Simanis, 1996), we asked whether overexpression of one of its budding yeast homologues could rescue the checkpoint defects of cells lacking Bub2, the budding yeast counterpart of Cdc16. To address this question, the DMA2 coding sequence was cloned under the control of the galactose-inducible GAL1 promoter (GAL1-DMA2) and integrated in single copy into the yeast genome. We first compared the kinetics of mitotic exit in GAL1-DMA2 versus wild-type cells in synchronized cultures grown in raffinose-containing medium (GAL1 promoter off), arrested in G1 with α factor and then released in the presence of galactose (GAL1 promoter on). No major differences could be seen between the two strains in the kinetics of Clb2 degradation, Sic1 accumulation, Clb2/Cdk1 kinase inactivation, and spindle disassembly (Figure 4A), suggesting that overproduction of Dma2 from the GAL1 promoter does not interfere with mitotic exit during an unperturbed cell cycle. To ask whether overexpression of DMA2 could rescue spindle checkpoint defects, wild-type and bub2Δ cells, either lacking or carrying the GAL1-DMA2 fusion, were treated as described above and then released from the G1 arrest in the presence of galactose and nocodazole, to depolymerize microtubules. As expected, in these conditions wild-type cells arrested in metaphase with 2C DNA contents, irrespective of the presence of GAL1-DMA2, and bub2Δ cells exited mitosis and entered into a new round of budding and DNA replication, accumulating 4C DNA contents. Conversely, DMA2 overexpression in bub2Δ cells mostly prevented them from rereplicating their DNA (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Overexpression of DMA2 prevents mitotic exit in nocodazole treated spindle checkpoint mutants. (A) Cultures of wild-type cells either lacking (wt) or carrying (GAL1-DMA2) one single copy of the GAL1-DMA2 fusion integrated at the URA3 locus were grown in YEPR, arrested in G1 by α factor, and released in YEPRG. When the percentage of budded cells was >90% (t = 105′) α factor was readded at the concentration of 10 μg/ml. Cells were harvested at the indicated times for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis (FACS) of DNA contents, kinetics of budding, nuclear division, and spindle elongation after immunostaining of α tubulin. At the same time points, cell samples were collected also for Western blot analysis with anti-Clb2 and anti-Sic1 (Swi6, loading control) and for Clb2/Cdk1 immunoprecipitations followed by kinase assays by using histone H1 as substrate. (B) Cultures of isogenic strains with the indicated genotypes, either lacking or carrying one copy of the GAL1-DMA2 fusion integrated at the URA3 locus and logarithmically growing in YEPR were arrested in G1 by α factor and released in YEPRG containing nocodazole (time 0). At the indicated times, DNA contents were analyzed by FACS. (C) Wild-type, GAL1-DMA2 (our unpublished data), mad2Δ, and mad2Δ GAL1-DMA2 strains, all carrying the tetO/tetR-GFP constructs to measure sister chromatid separation at subtelomeric regions, were treated as in A. At the indicated times, cell samples were collected for FACS analysis of DNA contents (left) and kinetics of sister chromatid separation (right).

Whereas Bub2 and Cdc16 inhibit mitotic exit and cytokinesis through similar pathways (Simanis, 2003), Mad2 belongs to a different branch of the mitotic checkpoint, which prevents sister chromatid separation and MEN activation via a different route (Gardner and Burke, 2000). It was therefore interesting to verify whether DMA2 overexpression also could suppress the checkpoint defects of cells lacking Mad2. To this end, wild-type, GAL1-DMA2, mad2Δ, and mad2Δ GAL1-DMA2 strains carrying the tetO/tetR-GFP constructs to monitor separation of sister chromatids at subtelomeric regions (Alexandru et al., 2001) were treated as described above. Upon spindle disassembly by nocodazole, wild-type and GAL1-DMA2 cells arrested with unseparated sister chromatids (Figure 4C) and 2C DNA contents (our unpublished data), whereas mad2Δ cells, as expected, lost sister chromatid cohesion and underwent a second round of DNA replication (Figure 4C). Overexpression of DMA2 in the latter cells could not prevent the onset of anaphase, but mostly inhibited rereplication (Figure 4C), suggesting that Dma2 does not influence the ability of Mad2 to inactivate Cdc20/APC, which in turn promotes sister chromatid separation (Musacchio and Hardwick, 2002), but rather intervenes more downstream in the pathway. Thus, high levels of Dma2 can prevent both mad2Δ and bub2Δ cells from exiting mitosis and entering into a new cell cycle, indicating that they might affect MEN activation under certain conditions.

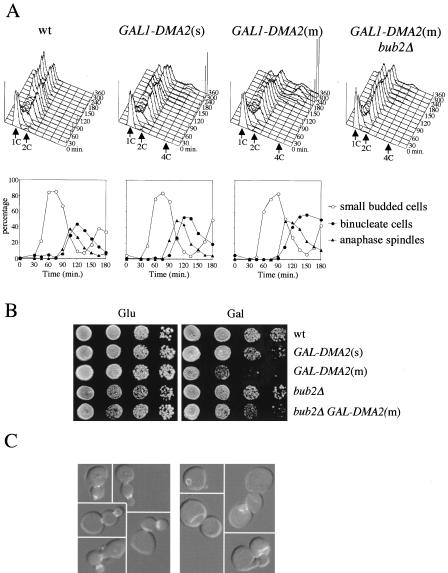

Overexpression of DMA2 Causes Cytokinetic Defects Partially Suppressed by BUB2 Deletion

To gain insights into the molecular mechanisms leading to suppression of mitotic checkpoint defects by DMA2 overexpression, we analyzed the effects of Dma2 high dosage during an unperturbed cell cycle. For this purpose, we monitored cell cycle progression under galactose-induced conditions of otherwise wild-type cells carrying either none, one single (s) or multiple tandem copies (m) of GAL1-DMA2 integrated in the genome. G1 synchronized cell cultures were released in the presence of galactose, and kinetics of DNA replication, budding, spindle assembly/breakdown, and nuclear division were monitored on fixed cells at different times after release. As shown in Figure 5A, wild-type cells could complete one division cycle within 120 min, as indicated by the reappearance of cells with 1C DNA contents after nuclear division and disassembly of anaphase spindles. Expression of GAL1-DMA2(s), as observed previously (Figure 4A), had only modest effects on cell cycle progression, causing at most a 15-min delay in spindle disassembly and cell division. However, compared with wild type, a higher percentage of GAL1-DMA2(s) cells with 2C DNA contents persisted throughout the course of the experiment and a small fraction of undivided cells occurred at later time points, accumulating as chains of cells with DNA contents higher than 2C (Figure 5A). These effects were magnified by expression of GAL1-DMA2(m), which allowed very few cells with 1C DNA contents to reaccumulate, whereas ∼30% of the cells occurred as rebudded, multinucleated cells with DNA contents higher than 2C at 240 min after induction (Figure 5A). Most of these cells could not be separated after cell wall digestion with zymolase (our unpublished data), suggesting that they arose from a cytokinetic failure. These cytokinetic defects did not correlate with inability to exit mitosis. In fact, GAL1-DMA2(m) cells could not only rebud and enter into a new round of DNA replication but also could disassemble their spindles, albeit more slowly than wild-type cells (Figure 5A), suggesting that high levels of Dma2 can, at most, delay mitotic exit, while more severely affecting cytokinesis.

Figure 5.

Overexpression of DMA2 interferes with cytokinesis and septin ring disassembly. (A) Cultures of wild-type cells, either untransformed (wt) or carrying one (s) or multiple (m) copies of the GAL1-DMA2 fusion integrated at the DMA2 locus, were grown in YEPR, synchronized in G1 with α factor, and released into YEPRG at time 0. Samples were withdrawn at the indicated time points for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis (FACS) analysis of DNA contents (top) and to score kinetics of budding, nuclear division and spindle elongation (bottom). Cell cycle progression of a bub2Δ GAL1-DMA2(m) cell culture under the same conditions was followed in parallel by FACS analysis. (B) Serial dilutions of the indicated cell cultures, either lacking or carrying a single (s) or multiple (m) copies of the GAL1-DMA2 fusion integrated at the DMA2 locus were spotted on YEPD (Glu) and YEPRG (Gal) plates and incubated for 3 d at 23°C. (C) Wild-type (W303) and GAL1-DMA2(m) (ySP3018) cells expressing a Cdc3-GFP fusion were grown in YEPR, synchronized with α factor, and released into YEPRG. At the time cells entered S phase of the second cell cycle (150′, as determined by FACS analysis), cells with two Cdc3-GFP rings or mispositioned GFP signals were scored (see text for details). Photographs show examples of GAL1-DMA2 cells that either deposit a new septin ring before disassembly of the previous one (left) or show mislocalized Cdc3-GFP signal (right).

By analogy to SIN inhibition by S. pombe Dma1 (Guertin et al., 2002), it was possible that the phenotypic effects caused by DMA2 overexpression were due to partial MEN inactivation. We therefore asked whether deletion of BUB2, encoding a well-characterized MEN inhibitor (Simanis, 2003), could restore normal cell cycle progression in cells expressing high Dma2 levels. Strikingly, the cytokinetic defects of GAL1-DMA2(m) cells could be almost totally rescued by inactivation of Bub2. In fact, GAL1-DMA2(m) bub2Δ cells were almost completely able to divide and reaccumulate with 1C DNA contents (Figure 5A). Furthermore, deletion of BUB2 partially rescued the lethality caused by GAL1-DMA2(m) overexpression (Figure 5B). We also analyzed whether the cytokinetic defects of GAL1-DMA2(m) cells could be rescued by inactivation of other mitotic inhibitors, such as the mitotic CDK inhibitory kinase Swe1 (Booher et al., 1993) and the Tem1 inhibitor Amn1 (Wang et al., 2003). In contrast to BUB2 deletion, neither AMN1 nor SWE1 deletion could alleviate the cytokinetic defects caused by DMA2 overexpression (Figure S1A, supplementary data).

To investigate in further detail the reasons for the cytokinetic failure observed upon overexpression of DMA2, we analyzed whether the septin ring was correctly positioned in GAL1-DMA2(m) cells compared with wild-type. In fact, a septin ring, which is an essential prerequisite for cytokinesis, is assembled at the G1/S transition at the site of bud emergence (Longtine et al., 1996) and is normally disassembled during mitotic exit in a Tem1-dependent manner (Lippincott et al., 2001). We found that indeed overproduction of Dma2 caused remarkable differences in the kinetics of septin ring disassembly compared with wild type. In fact, after release in the presence of galactose of G1 synchronized cultures of wild-type and GAL1-DMA2(m) cells carrying the Cdc3-GFP fusion, no cells with two septin rings were seen among >300 wild-type cells, whereas 17% of GAL1-DMA2(m) cells showed a new septin ring at the site of bud emergence before disassembly of the old one (Figure 5C, left) at 150 min after release from G1, when cells entered into a new round of budding and DNA replication. Interestingly, these cells rebudded only from the previous bud and never from the mother cell, consistently with a role of the septin ring in creating a physical barrier to the diffusion of cell polarity determinants through the bud neck (Barral et al., 2000). A fraction of GAL1-DMA2(m) cells (14 vs. 1.2% of wild-type cells) showed also aberrant septin ring deposition (Figure 5C, right). Together, these data suggest that overexpression of DMA2 affects normal septin ring deposition and disassembly, thus causing cytokinetic defects.

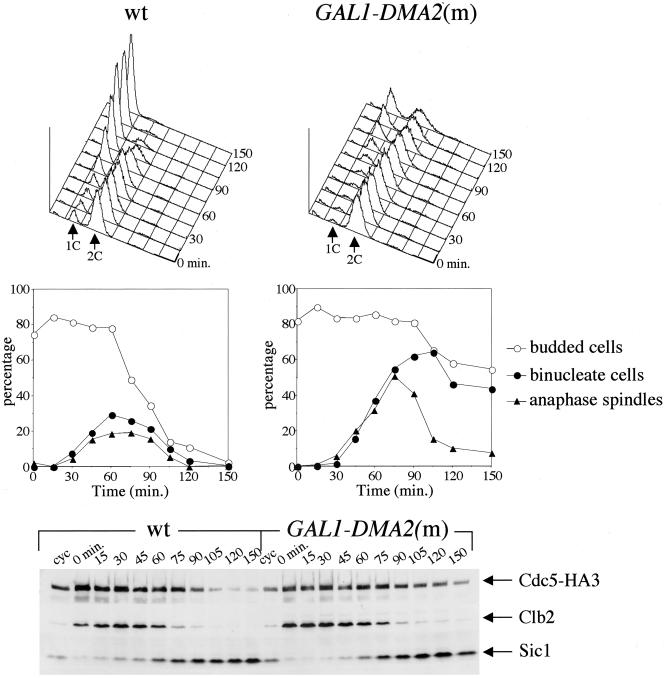

Because we found that spindle disassembly was somewhat delayed in DMA2-overexpressing cells (Figure 5A), we also analyzed more accurately to what extent mitotic exit could be compromised in such cells by checking directly MEN activation in late mitosis. As a readout, we analyzed by Western blot degradation of two APC substrates, the Polo kinase Cdc5 and the main mitotic cyclin Clb2, as well as reappearance of the CDK inhibitor Sic1, both events depending on MEN-dependent activation of the Cdc14 phosphatase at the end of mitosis (Shirayama et al., 1998; Visintin et al., 1998). Wild-type and GAL1-DMA2(m) cells were arrested in metaphase by nocodazole treatment and then released in the presence of galactose and α factor, to arrest them in the next G1 phase. Consistently with a cytokinetic defect, cell division kinetics was very slow in GAL1-DMA2(m) cells, and DMA2 overexpression caused accumulation of cells with long anaphase spindles compared with wild type, suggesting that spindle disassembly was transiently delayed (Figure 6). However, spindles eventually disassembled between 90 and 120 min. Similarly, Clb2 was degraded and Sic1 reappeared with ∼15-min delay with respect to wild type (Figure 6). Proteolysis of a HA-tagged version of Cdc5 was more dramatically affected and was not completed by the end of the experiment (150 min) in GAL1-DMA2(m) cells, whereas it was already apparent at 105 min in wild-type cells under the same conditions. Therefore, Dma2 high levels seem to interfere with some aspects of mitotic exit.

Figure 6.

Mitotic exit upon DMA2 overexpression. Wild-type (wt, ySP939) and GAL1-DMA2m (ySP3318) cells expressing HA-tagged Cdc5 (Cdc5-HA3) were grown in YEPR, synchronized in metaphase by nocodazole treatment (5 μg/ml), and released at time 0 into YEPRG containing α factor to arrest cells in the next G1. Cell samples were withdrawn at the indicated times for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of DNA contents (top); kinetics of budding, nuclear division, and spindle elongation (middle); and Western blot analysis of Cdc5-HA3, Clb2, and Sic1 (bottom).

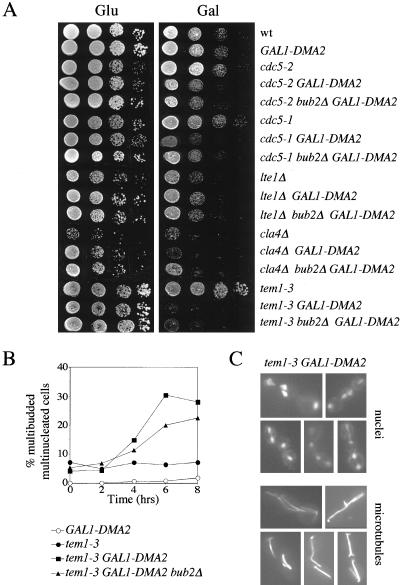

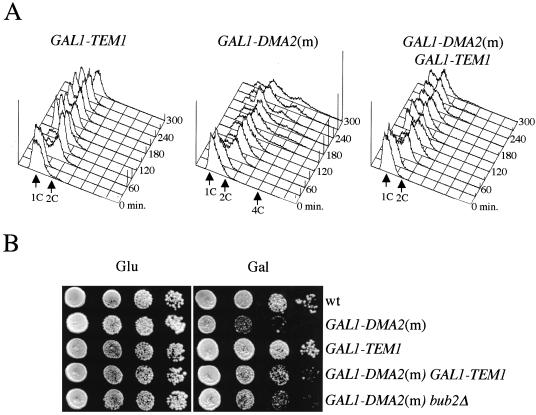

Overexpression of DMA2 Interferes with Tem1 Activation

Because the data so far suggested that Dma1 and Dma2 could impinge on the same pathway as Bub2, we asked whether their target might be the MEN, and looked for genetic interactions between MEN components and Dma2. To this end, we analyzed the effects of GAL1-DMA2(s) expression, which has only minor effects on cell proliferation of otherwise wild-type cells, in some mutants defective at the top of the MEN cascade, such as cdc5-1, cdc5-2, lte1Δ, cla4Δ, and tem1-3. In all mutants, except for lte1Δ, we could see a toxic effect on cell proliferation caused by ectopic DMA2 expression even at 25°C, permissive temperature for the above-mentioned mutants. Therefore, high levels of Dma2 are deleterious when the MEN is partially compromised (Figure 7). In two mutants, cdc5-1 and cla4Δ, synthetic growth effects caused by GAL1-DMA2 could be partially rescued by BUB2 deletion. The tem1-3 mutant was the most sensitive to DMA2 overexpression, and upon galactose induction accumulated cells rebudding from the previous bud and eventually containing multiple nuclei and mitotic spindles (Figure 7, B and C). This phenotype can also be seen in a low percentage of tem1-3 cells at the permissive temperature (Figure 7B), allowing to speculate that Dma2 might act close to Tem1 in the MEN. If this were the case, we would expect overexpression of TEM1 to counteract the cytokinetic defects caused by high levels of Dma2, like BUB2 deletion does (Figure 5A). Indeed, TEM1 overexpression from the GAL1 promoter allowed cells expressing GAL1-DMA2(m) to undergo cytokinesis with wild-type kinetics (Figure 8A), suggesting that Tem1 might become limiting for promoting mitotic exit and cytokinesis in DMA2-overexpressing cells. In addition, GAL1-TEM1 expression also could restore cell viability in Dma2 overproducing cells more efficiently than BUB2 deletion (Figure 8B). Because S. pombe Dma1 was proposed to antagonize the polo kinase (Guertin et al., 2002), we wondered whether overproduction of the polo kinase Cdc5 could restore proper cell division in cells containing high Dma2 levels. However, overexpression of CDC5, unlike that of TEM1, did not suppress either cytokinetic defects or cell lethality of GAL1-DMA2(m) cells (Figure S1, A and B, supplementary data).

Figure 7.

DMA2 overexpression is toxic for MEN mutants. (A) Serial dilutions of the indicated cell cultures, lacking or carrying one copy of the GAL1-DMA2 fusion integrated at the URA3 locus, were spotted on either YEPD (Glu) or YEPRG (Gal) plates and incubated for two days at 25°C. (B) Cultures of the indicated strains were grown in YEPR at 25°C and induced with 1% galactose at time 0. Cell samples were withdrawn every 2 h for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of DNA contents (our unpublished data), kinetics of accumulation of multinucleate cells (graph) and in situ immunostaining of α tubulin (our unpublished data). (C) Examples of nuclei and microtubules of tem1-3 GAL1-DMA2 multinucleated cells from the experiment in B) after 4 h of galactose induction are shown.

Figure 8.

TEM1 overexpression rescues cytokinetic and growth defects caused by Dma2 high levels. (A) Cultures of isogenic strains with the indicated genotypes (ySP3616, ySP3657, and ySP3721), logarithmically growing in YEPR, were arrested in G1 by α factor and released in YEPRG at time 0. Cell samples were withdrawn at the indicated times for fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis of the DNA contents. (B) Serial dilutions of the indicated cell cultures were spotted on YEPD (Glu) or YEPRG (Gal) plates and incubated for 3 d at 23°C.

DISCUSSION

A Role for Dma1 and Dma2 in Septin Ring Assembly

The first step in nuclear positioning occurs through migration of the spindle toward the bud neck and requires a Kar9-dependent pathway that involves, besides the cortical determinant Kar9 (Miller and Rose, 1998), the plus-end microtubule binding protein Bim1, that interacts with Kar9 (Korinek et al., 2000; Lee et al., 2000); the Bni1 protein, required for Kar9 proper localization (Miller et al., 1999); and the microtubule motor Kip3 (Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997; DeZwaan et al., 1997). A second pathway, leading to insertion of the spindle through the bud neck, depends on cytoplasmic dynein (Cottingham and Hoyt, 1997; DeZwaan et al., 1997) and on the cortical protein Num1 (Heil-Chapdelaine et al., 2000). The two pathways are presumably functionally redundant, because inactivation of any gene of one pathway in the absence of any component of the second pathway is often lethal or severely deleterious. Recently, septins also have been implicated in spindle positioning by providing a cortical cue for microtubule capture, and based on genetic interactions have been proposed to act in the nuclear positioning Kar9 pathway (Kusch et al., 2002). We now show that Dma1 and Dma2 might have a direct role in septin ring deposition and might therefore control spindle positioning. In fact, lack of both Dma1 and Dma2 compromise septin ring assembly and have additive effects with cla4 mutations. In addition, overexpression of Dma2 delays septin ring disassembly at the end of mitosis. We find that the lack of Dma1 and Dma2 does not cause synthetic growth defects when combined with deletion of either KAR9 or KIP3 (our unpublished data), whereas it confers a temperature-sensitive growth phenotype to dyn1Δ cells, which would suggest that Dma1 and Dma2 might act in the Kar9-dependent pathway. However, the finding that DMA1/DMA2 deletion causes additive defects on spindle positioning when combined with the lack of either Bim1 or Bni1 argues against this simple view, suggesting that Dma1 and Dma2 might act in a novel spindle positioning pathway. This is still an open question, since genetic interactions do not always reflect the complex functional interactions taking place between components of the spindle positioning/orientation pathways, because other exceptions to the above-mentioned simple genetic rule have been previously observed. For example, deletion of BIM1 is lethal in kip3Δ cells, despite Bim1 and Kip3 supposedly belong to the same spindle positioning pathway (Tong et al., 2001). In addition, despite that Cla4 also should participate to the Kar9-dependent pathway by virtue of its involvement in septin ring organization (Cvrckova et al., 1995), it is essential in a bni1Δ background (Goehring et al., 2003).

How Dma1 and Dma2 regulate septin ring organization is unknown at the moment. Septins undergo different posttranslational modifications, including covalent attachment of the ubiquitin-related peptide SUMO between the onset of anaphase and cytokinesis (Johnson and Blobel, 1999). Multiple mutations in septin sumoylation sites prevents the disappearance of septin rings from old bud sites, leading to the proposal that sumoylation of septins promotes disassembly of the septin ring, either directly or indirectly, by preventing/inducing other posttranslational modifications, such as ubiquitination (Johnson and Blobel, 1999). Based on the failure of DMA2-overexpressing cells to timely disassemble septin rings, and on the notion that Dma1 and Dma2 are RING finger-containing proteins, and therefore possibly part of an E3 ubiquitin-ligase (Joazeiro and Weissman, 2000), an attractive hypothesis that is worth further investigation is that Dma1 and Dma2 might directly mediate septins' ubiquitination or sumoylation.

The MEN as a Target of Dma1/Dma2

Fission yeast Dma1 has been found to prevent activation of the SIN, thereby inhibiting cytokinesis, and to interfere with the correct localization of the Polo kinase Plo1 and other SIN regulators (Guertin et al., 2002). In addition, its human homologue Chfr is a ubiquitin ligase that ubiquitinates the Polo-like kinase Plk1 in Xenopus cell extracts (Kang et al., 2002). The following lines of evidence suggest that the mitotic exit network could be a target of Dma1 and Dma2 regulation in budding yeast: 1) moderate DMA2 overexpression can suppress the ability of spindle checkpoint mutants to exit mitosis in the presence of nocodazole; 2) increased levels of Dma2 that are perfectly tolerated by wild-type cells are extremely toxic specifically for some MEN mutants; and 3) strong DMA2 overexpression causes mitotic exit and cytokinesis defects that can be rescued by either deletion of BUB2 or simultaneous overexpression of TEM1. Indeed, all these data could be consistent with a model where Dma1 and Dma2 antagonize the activity of the Polo kinase Cdc5, because one important function of Cdc5 in the MEN is to down-regulate the GTPase-activating protein Bub2/Bfa1, thus allowing Tem1 activation (Hu et al., 2001). However, so far we have been unable to find any correlation between Dma1/Dma2 activation and Cdc5 regulation. In fact, Cdc5 protein levels are unaltered in dma1Δ dma2Δ cells (Figure S2A, supplementary material) and more stable, rather than more labile, in DMA2-overexpressing cells (Figure 6). Moreover, high levels of Dma2 do not interfere with separation of sister telomeres (Figure S2B, supplementary material), which depends upon Cdc5 activity (Alexandru et al., 2001). Finally, cytokinetic defects caused by DMA2 overexpression are not rescued by high Cdc5 levels (Figure S1A, supplementary material).

Another possibility is that the MEN inhibitory function of Dma1/Dma2 is to inhibit Tem1 through the GAP Bub2/Bfa1. However, we think this is not the case, because BUB2 deletion only partially counteracts the deleterious effects on cytokinesis of Dma2 high levels and mostly does not suppress their lethal effects in MEN mutants. Moreover, DMA1/DMA2 deletion dramatically increases the benomyl sensitivity of bub2Δ cells (our unpublished observations), suggesting that Dma1/Dma2 and Bub2 might operate in different pathways. Accordingly, DMA2 overexpression can suppress the spindle checkpoint defects of bub2Δ cells. Therefore, we rather suspect that Dma1 and Dma2 might impinge more directly on Tem1 activation. In fact, TEM1 overexpression can partially counteract the inhibitory effects on cytokinesis and the toxicity on growth caused by high levels of Dma2. In addition, depletion of Tem1 in conditions that allow mitotic exit causes defects in septin ring disassembly (Lippincott et al., 2001) that are remarkably similar to those observed in DMA2-overexpressing cells.

Despite our efforts, how Tem1 inhibition by Dma1/Dma2 could be achieved has not yet been elucidated. In fact, Tem1 protein levels, localization at SPBs or interaction with Cdc15 (another MEN component) seemed to be unaffected by either DMA1/DMA2 deletion or DMA2 overexpression (our unpublished data). Accordingly, deletion of AMN1, which inhibits Tem1/Cdc15 interaction and MEN activation (Wang et al., 2003), did not rescue the deleterious effects caused by high levels of Dma2 (Figure S1A/B, supplementary material), suggesting that Dma2 acts independently of Amn1. Because DMA2 overexpression seems to affect cytokinesis more than mitotic exit, it is also possible that only a special pool of Tem1 is regulated by Dma1/Dma2 or that the latter proteins and Tem1 antagonistically act in parallel to regulate downstream MEN components. It is now well established that MEN components have cytokinetic functions independent of Cdc14 release from the nucleolus and inactivation of mitotic CDKs (Shou et al., 1999; Lippincott et al., 2001; Park et al., 2003). Further experiments will be required to clarify these points. Being Dma1 and Dma2 possibly part of an E3 ubiquitin ligase, the identification of their substrates will be critical to understand their possible role in MEN regulation. Interestingly, a high-throughput mass spectrometric analysis indicates that Dma1 and Dma2, besides interacting with each other, physically associate with a F-box protein (the gene product of YNL311), which in turn interacts with ubiquitin (Ho et al., 2002), further supporting their possible involvement in a ubiquitination pathway.

Dma1/Dma2 and the Spindle Position Checkpoint

S. pombe Dma1 is required to delay mitotic exit and septum formation when spindle function is compromised (Murone and Simanis, 1996). Its human homologue Chfr is instead part of a mitotic stress checkpoint that delays metaphase entry upon transient treatment with drugs interfering with microtubule dynamics (Scolnick and Halazonetis, 2000). Accordingly, Chfr was also found to inhibit the Cdc2 kinase at the G2/M transition by prolonging its inhibitory tyrosine 15 phosphorylated state (Kang et al., 2002). We showed that DMA2 overexpression interferes with mitotic exit and cytokinesis, but apparently not with the onset of anaphase. In addition, the deleterious effects caused by high Dma2 levels are not rescued, but rather enhanced, by deletion of SWE1 (Figure S1A, supplementary material) that encodes the Wee1-like inhibitory kinase responsible for tyrosine 15 phosphorylation of mitotic CDKs (Booher et al., 1993). Therefore, Dma1 and Dma2 seem to have functions closer to their fission yeast, rather than human, counterpart.

The concomitant lack of Dma1 and Dma2 impairs the spindle position checkpoint. A striking correlation can be drawn between the involvement of Dma1/Dma2 in this checkpoint and their role in septin ring assembly. In fact, septins have recently been shown to prevent inappropriate mitotic exit when cytoplasmic microtubules do not interact properly with the bud neck (Castillon et al., 2003). Unlike S. pombe Dma1, S. cerevisiae Dma1 and Dma2 are not required to delay cell cycle progression in the presence of nocodazole. In addition, whereas lack of Dma1 and Dma2 allows unscheduled mitotic exit in dynein mutants, it does not have any effect in the absence of Kar9 (our unpublished observations), suggesting that Dma1 and Dma2 are required to respond only to some kinds of spindle misposition signals. In this respect, Dma1 and Dma2 share remarkable similarities with Bim1, which is involved in spindle positioning/orientation (Tirnauer et al., 1999), and also has been implicated in a checkpoint that delays cytokinesis in the presence of mispositioned spindles specifically caused by dynactin mutation (Muhua et al., 1998). The surprising observation that bim1Δ cells do not necessarily undergo premature cytokinesis in the presence of spindles mispositioned by other means (Tirnauer et al., 1999; Adames et al., 2001), together with our similar observation on dma1Δ dma2Δ cells, suggests that defects in dynein/dynactin might generate different signals from those arising by other kinds of spindle positioning errors.

Interestingly, human Chfr is missing in several tumor cell lines (Scolnick and Halazonetis, 2000), whereas the Bim1 homologue EB1 is associated with the tumor suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli protein (Su et al., 1995), suggesting that perhaps these proteins are crucial to maintain genome stability. A detailed characterization of the errors they detect might therefore help to shed light on the processes at the basis of tumor progression.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Tony Hyman, John Kilmartin, Kyung Lee, Kim Nasmyth, Mike Tyers, and Wolfgang Zachariae for providing strains and reagents; to Alessia Beretta for performing some preliminary experiments on dma1Δ dma2Δ mutants; and to Maria Pia Longhese for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by grants from Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro to S.P., and Cofinanziamento 2003 Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca-Università di Milano-Bicocca, Fondo per gli investimenti della Ricerca di Base, and Progetto Strategico Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca-Legge 449/97 to G.L.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0094. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04-02-0094.

Online version of this article contains supporting material. Online version is available at www.molbiolcell.org.

References

- Adames, N.R., and Cooper, J.A. (2000). Microtubule interactions with the cell cortex causing nuclear movements in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 149, 863-874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adames, N.R., Oberle, J.R., and Cooper, J.A. (2001). The surveillance mechanism of the spindle position checkpoint in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 153, 159-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandru, G., Uhlmann, F., Mechtler, K., Poupart, M., and Nasmyth, K. (2001). Phosphorylation of the cohesin subunit Scc1 by Polo/Cdc5 kinase regulates sister chromatid separation in yeast. Cell 105, 459-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandru, G., Zachariae, W., Schleiffer, A., and Nasmyth, K. (1999). Sister chromatid separation and chromosome re-duplication are regulated by different mechanisms in response to spindle damage. EMBO J. 18, 2707-2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardin, A.J., Visintin, R., and Amon, A. (2000). A mechanism for coupling exit from mitosis to partitioning of the nucleus. Cell 102, 21-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barral, Y., Mermall, V., Mooseker, M.S., and Snyder, M. (2000). Compartmentalization of the cell cortex by septins is required for maintenance of cell polarity in yeast. Mol. Cell. 5, 841-851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach, D.L., Thibodeaux, J., Maddox, P., Yeh, E., and Bloom, K. (2000). The role of the proteins Kar9 and Myo2 in orienting the mitotic spindle of budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 10, 1497-1506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloecher, A., Venturi, G.M., and Tatchell, K. (2000). Anaphase spindle position is monitored by the BUB2 checkpoint. Nat. Cell Biol. 2, 556-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booher, R.N., Deshaies, R.J., and Kirschner, M.W. (1993). Properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae wee1 and its differential regulation of p34CDC28 in response to G1 and G2 cyclins. EMBO J. 12, 3417-3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillon, G.A., Adames, N.R., Rosello, C.H., Seidel, H.S., Longtine, M.S., Cooper, J.A., and Heil-Chapdelaine, R.A. (2003). Septins have a dual role in controlling mitotic exit in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 13, 654-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottingham, F.R., Gheber, L., Miller, D.L., and Hoyt, M.A. (1999). Novel roles for saccharomyces cerevisiae mitotic spindle motors. J. Cell Biol. 147, 335-350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cottingham, F.R., and Hoyt, M.A. (1997). Mitotic spindle positioning in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is accomplished by antagonistically acting microtubule motor proteins. J. Cell Biol. 138, 1041-1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cvrckova, F., De Virgilio, C., Manser, E., Pringle, J.R., and Nasmyth, K. (1995). Ste20-like protein kinases are required for normal localization of cell growth and for cytokinesis in budding yeast. Genes Dev. 9, 1817-1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeZwaan, T.M., Ellingson, E., Pellman, D., and Roof, D.M. (1997). Kinesin-related KIP3 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is required for a distinct step in nuclear migration. J. Cell Biol. 138, 1023-1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fankhauser, C., Marks, J., Reymond, A., and Simanis, V. (1993). The S. pombe cdc16 gene is required both for maintenance of p34cdc2 kinase activity and regulation of septum formation: a link between mitosis and cytokinesis? EMBO J. 12, 2697-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fesquet, D., Fitzpatrick, P.J., Johnson, A.L., Kramer, K.M., Toyn, J.H., and Johnston, L.H. (1999). A Bub2p-dependent spindle checkpoint pathway regulates the Dbf2p kinase in budding yeast. EMBO J. 18, 2424-2434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraschini, R., Formenti, E., Lucchini, G., and Piatti, S. (1999). Budding yeast Bub2 is localized at spindle pole bodies and activates the mitotic checkpoint via a different pathway from Mad2. J. Cell Biol. 145, 979-991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, R.D., and Burke, D.J. (2000). The spindle checkpoint: two transitions, two pathways. Trends Cell Biol. 10, 154-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geymonat, M., Spanos, A., Smith, S.J., Wheatley, E., Rittinger, K., Johnston, L.H., and Sedgwick, S.G. (2002). Control of mitotic exit in budding yeast. In vitro regulation of Tem1 GTPase by Bub2 and Bfa1. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 28439-28445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goehring, A.S., Mitchell, D.A., Tong, A.H., Keniry, M.E., Boone, C., and Sprague, G.F., Jr. (2003). Synthetic lethal analysis implicates Ste20p, a p21-activated protein kinase, in polarisome activation. Mol. Biol. Cell 14, 1501-1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guertin, D.A., Venkatram, S., Gould, K.L., and McCollum, D. (2002). Dma1 prevents mitotic exit and cytokinesis by inhibiting the septation initiation network (SIN). Dev. Cell 3, 779-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil-Chapdelaine, R.A., Oberle, J.R., and Cooper, J.A. (2000). The cortical protein num1p is essential for dynein-dependent interactions of microtubules with the cortex. J. Cell Biol. 151, 1337-1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y., et al. (2002). Systematic identification of protein complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by mass spectrometry. Nature 415, 180-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, F., Wang, Y., Liu, D., Li, Y., Qin, J., and Elledge, S.J. (2001). Regulation of the Bub2/Bfa1 GAP complex by Cdc5 and cell cycle checkpoints. Cell 107, 655-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joazeiro, C.A., and Weissman, A.M. (2000). RING finger proteins: mediators of ubiquitin ligase activity. Cell 102, 549-552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.S., and Blobel, G. (1999). Cell cycle-regulated attachment of the ubiquitin-related protein SUMO to the yeast septins. J. Cell Biol. 147, 981-994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, D., Chen, J., Wong, J., and Fang, G. (2002). The checkpoint protein Chfr is a ligase that ubiquitinates Plk1 and inhibits Cdc2 at the G2 to M transition. J. Cell Biol. 156, 249-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korinek, W.S., Copeland, M.J., Chaudhuri, A., and Chant, J. (2000). Molecular linkage underlying microtubule orientation toward cortical sites in yeast. Science 287, 2257-2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusch, J., Meyer, A., Snyder, M.P., and Barral, Y. (2002). Microtubule capture by the cleavage apparatus is required for proper spindle positioning in yeast. Genes Dev. 16, 1627-1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L., Klee, S.K., Evangelista, M., Boone, C., and Pellman, D. (1999). Control of mitotic spindle position by the Saccharomyces cerevisiae formin Bni1p. J. Cell Biol. 144, 947-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L., Tirnauer, J.S., Li, J., Schuyler, S.C., Liu, J.Y., and Pellman, D. (2000). Positioning of the mitotic spindle by a cortical-microtubule capture mechanism. Science 287, 2260-2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, W.L., Oberle, J.R., and Cooper, J.A. (2003). The role of the lissencephaly protein Pac1 during nuclear migration in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 160, 355-364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew, D.J., and Reed, S.I. (1995). A cell cycle checkpoint monitors cell morphogenesis in budding yeast. J. Cell Biol. 129, 739-749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippincott, J., Shannon, K.B., Shou, W., Deshaies, R.J., and Li, R. (2001). The Tem1 small GTPase controls actomyosin and septin dynamics during cytokinesis. J. Cell Sci. 114, 1379-1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longtine, M.S., DeMarini, D.J., Valencik, M.L., Al-Awar, O.S., Fares, H., De Virgilio, C., and Pringle, J.R. (1996). The septins: roles in cytokinesis and other processes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 8, 106-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maniatis, T., Fritsch, E.F., and Sambrook, J. (1992). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press.

- Michaelis, C., Ciosk, R., and Nasmyth, K. (1997). Cohesins: chromosomal proteins that prevent premature separation of sister chromatids. Cell 91, 35-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R.K., Matheos, D., and Rose, M.D. (1999). The cortical localization of the microtubule orientation protein, Kar9p, is dependent upon actin and proteins required for polarization. J. Cell Biol. 144, 963-975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, R.K., and Rose, M.D. (1998). Kar9p is a novel cortical protein required for cytoplasmic microtubule orientation in yeast. J. Cell Biol. 140, 377-390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhua, L., Adames, N.R., Murphy, M.D., Shields, C.R., and Cooper, J.A. (1998). A cytokinesis checkpoint requiring the yeast homologue of an APC-binding protein. Nature 393, 487-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murone, M., and Simanis, V. (1996). The fission yeast dma1 gene is a component of the spindle assembly checkpoint, required to prevent septum formation and premature exit from mitosis if spindle function is compromised. EMBO J. 15, 6605-6616. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musacchio, A., and Hardwick, K.G. (2002). The spindle checkpoint: structural insights into dynamic signalling. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 3, 731-741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.J., Song, S., Lee, P.R., Shou, W., Deshaies, R.J., and Lee, K.S. (2003). Loss of CDC5 function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae leads to defects in Swe1p regulation and Bfa1p/Bub2p-independent cytokinesis. Genetics 163, 21-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G., Hofken, T., Grindlay, J., Manson, C., and Schiebel, E. (2000). The Bub2p spindle checkpoint links nuclear migration with mitotic exit. Mol. Cell 6, 1-10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuyler, S.C., and Pellman, D. (2001). Search, capture and signal: games microtubules and centrosomes play. J. Cell Sci. 114, 247-255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwob, E., Bohm, T., Mendenhall, M.D., and Nasmyth, K. (1994). The B-type cyclin kinase inhibitor p40SIC1 controls the G1 to S transition in S. cerevisiae [see comments] [published erratum appears in Cell 1996 Jan 12;84(1):following 174]. Cell 79, 233-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolnick, D.M., and Halazonetis, T.D. (2000). Chfr defines a mitotic stress checkpoint that delays entry into metaphase. Nature 406, 430-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheeman, B., Carvalho, P., Sagot, I., Geiser, J.R., Kho, D., Hoyt, M.A., and Pellman, D. (2003). Determinants of S. cerevisiae dynein localization and activation: implications for the mechanism of spindle positioning. Curr. Biol. 13, 364-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, F. (1991). Getting started with yeast. Methods Enzymol. 194, 3-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirayama, M., Zachariae, W., Ciosk, R., and Nasmyth, K. (1998). The Polo-like kinase Cdc5p and the WD-repeat protein Cdc20p/fizzy are regulators and substrates of the anaphase promoting complex in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 17, 1336-1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou, W., Seol, J.H., Shevchenko, A., Baskerville, C., Moazed, D., Chen, Z.W., Jang, J., Charbonneau, H., and Deshaies, R.J. (1999). Exit from mitosis is triggered by Tem1-dependent release of the protein phosphatase Cdc14 from nucleolar RENT complex. Cell 97, 233-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simanis, V. (2003). Events at the end of mitosis in the budding and fission yeasts. J. Cell Sci. 116, 4263-4275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su, L.K., Burrell, M., Hill, D.E., Gyuris, J., Brent, R., Wiltshire, R., Trent, J., Vogelstein, B., and Kinzler, K.W. (1995). APC binds to the novel protein EB1. Cancer Res. 55, 2972-2977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, D.S., and Huffaker, T.C. (1992). Astral microtubules are not required for anaphase B in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 119, 379-388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surana, U., Amon, A., Dowzer, C., McGrew, J., Byers, B., and Nasmyth, K. (1993). Destruction of the CDC28/CLB mitotic kinase is not required for the metaphase to anaphase transition in budding yeast. EMBO J. 12, 1969-1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirnauer, J.S., O'Toole, E., Berrueta, L., Bierer, B.E., and Pellman, D. (1999). Yeast Bim1p promotes the G1-specific dynamics of microtubules. J. Cell Biol. 145, 993-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.H., et al. (2001). Systematic genetic analysis with ordered arrays of yeast deletion mutants. Science 294, 2364-2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin, R., Craig, K., Hwang, E.S., Prinz, S., Tyers, M., and Amon, A. (1998). The phosphatase Cdc14 triggers mitotic exit by reversal of Cdk-dependent phosphorylation. Mol. Cell 2, 709-718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach, A., Brachat, A., Pohlmann, R., and Philippsen, P. (1994). New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10, 1793-1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y., Shirogane, T., Liu, D., Harper, J.W., and Elledge, S.J. (2003). Exit from exit: resetting the cell cycle through Amn1 inhibition of G protein signaling. Cell 112, 697-709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh, E., Skibbens, R.V., Cheng, J.W., Salmon, E.D., and Bloom, K. (1995). Spindle dynamics and cell cycle regulation of dynein in the budding yeast, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Cell Biol. 130, 687-700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, H., Pruyne, D., Huffaker, T.C., and Bretscher, A. (2000). Myosin V orientates the mitotic spindle in yeast. Nature 406, 1013-1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae, W., and Nasmyth, K. (1999). Whose end is destruction: cell division and the anaphase-promoting complex. Genes Dev. 13, 2039-2058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.