Abstract

The 2005 federal Deficit Reduction Act made proof of citizenship a requirement for Medicaid eligibility. We examined the effects on visits to Oregon’s Medicaid family planning services eighteen months after the citizenship requirement was implemented. We analyzed 425,381 records of visits that occurred between May 2005 and April 2008 and found that, compared to the eighteen-month period before the mandate went into effect, visits declined by 33 percent. We conclude that Medicaid citizenship documentation requirements have been burdensome for Oregon Family Planning Expansion Project patients and costly for health care providers, reducing access to family planning and preventive measures and increasing the strain on the safety net.

Under Section 1115 of the Social Security Act, the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has the authority to grant Medicaid waivers. These allow states to test novel service delivery systems, alter eligibility criteria, and change the scope of coverage for eligible recipients. Twenty-seven states, including Oregon, have been granted Section 1115 waivers to expand Medicaid eligibility for family planning services to people who do not meet the eligibility requirements for regular Medicaid.1 Through these waivers, states serve an estimated two million women and families in need every year, while also generating sizable savings for federal and state governments.2,3

The momentum of waiver programs may have been stalled or reversed by federal regulations stemming from the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005 that required states to collect proof of citizenship from all Medicaid applicants.

Background

The Deficit Reduction Act mandated that states collect “satisfactory documentary evidence” of citizenship from Medicaid applicants, to qualify for federal matching funds for services provided.4 Previously, it had been sufficient for Medicaid applicants to attest to their U.S. citizenship under penalty of perjury, and there was little evidence of citizenship-related fraud.5,6 Ironically, the Deficit Reduction Act also added new requirements to the Medicaid application process after states had spent several years simplifying enrollment processes to reduce enrollment barriers for eligible people.7–10

Reports suggest that federal citizenship documentation requirements may be counteracting efforts by states to simplify the Medicaid application process. Nine months after the DRA requirements took effect, twenty-two states reported that Medicaid enrollment had declined as a result of the requirements.11 States also reported increases in the amount of time needed to process applications, despite specific state efforts designed to minimize the regulations’ impact.11

Data from a July 2008 survey of state Medicaid directors corroborate earlier observations: About half of states continued to report longer processing times, and an increased number of applicants were denied Medicaid coverage.12 Most published reports have not quantified the requirements’ effects on the enrollment and utilization patterns of individual recipients.

OREGON’S FAMILY PLANNING EXPANSION PROJECT

Oregon’s 1115 family planning waiver began in 1999 and is known as the Family Planning Expansion Project. Covered services include cervical cancer screening, physical exams, and counseling and education about birth control and reproductive health. Clients, the vast majority of whom are uninsured, typically use the waiver to access recommended annual exams and up to one year’s supply of their chosen method of birth control. The Family Planning Expansion Project allows women and their families to avoid pregnancies they don’t want and plan for ones they do. The project also provides access to preconception services, cancer screening, and measures to prevent or detect sexually transmitted infections.

Adults and teens with family incomes under 185 percent of the federal poverty level are eligible for these services. Teens’ eligibility can be determined based on their individual incomes if they do not know their families’ income, and cannot find out the answer without compromising their ability to obtain family planning services confidentially. As is customary for family planning services delivered to all Medicaid clients, the federal government pays 90 percent of the cost of services billed to it by the Oregon Family Planning Expansion Project and prohibits any cost-sharing requirements for enrollees.

To maximize access to the program, Family Planning Expansion Project clients are enrolled at the point of service, typically a clinic. Clients are served through a network of about 160 local clinics operated by county health departments, federally qualified health centers, Planned Parenthood, and private providers. More than two-thirds of the sites can be considered family planning safety-net clinics by virtue of their status as federally qualified health centers, rural health centers, or Title X grant recipients. (Title X is a federal family planning program enacted in 1970.) These designations require clinics to serve anyone seeking reproductive health care, regardless of insurance status or ability to pay.

Before 2006, eligibility for services through Oregon’s Family Planning Expansion Project was based on just three criteria: Oregon residency, income under 185 percent of poverty, and U.S. citizenship or lawful permanent residency. No documentation was required for these criteria until the 2005 Deficit Reduction Act went into effect. For the Family Planning Expansion Project, implementation of the federal citizenship documentation requirements coincided with two other eligibility changes required by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Under these changes, teen applicants were required to provide their Social Security numbers, and applicants of any age who had so-called creditable insurance coverage were no longer considered eligible for services through the Family Planning Expansion Project.

Prior to 2006, collection of Social Security numbers from teen applicants was encouraged but not mandatory, and the Family Planning Expansion Project could be billed secondary to private insurance. In addition, a state law requiring insurers to offer coverage for prescription contraceptives when other prescription drugs are covered in the policy went into effect in January 2008, more than a year after DRA implementation. Because the mandate occurred late in the study period and affected fewer than 10 percent of Oregonians, we did not believe that it would interact significantly with the policies under examination here.

Oregon’s Family Planning Expansion Project represents an interesting case study of the impact of citizenship documentation regulations because of the relative ease of enrollment in the state’s program prior to 2006. Further, the case study provides the opportunity for analysis of a unique state effort to mitigate the impact of the citizenship documentation requirements on the population served by the project.

Oregon’s family planning program offered “one-time exception” visits, at which all usual family planning services were available and clients were given the opportunity and assistance to acquire needed documentation for full-time participation in the program. These “one-time exception” visits were designed to preserve same-day access to family planning services for clients, and to ensure consistent reimbursement for participating health care providers.

Consistent reimbursement is important for these providers because many are obligated by law to offer care even without compensation. Access to affordable family planning services is critical to women’s ability to plan and space their pregnancies as desired. It is estimated that rates of unintended pregnancy and abortion among low-income women would double in the absence of publicly funded family planning services.13 Use of the “one-time exception” visits is an indication of demand for family planning services that would have been unmet without extraordinary state-level efforts.

Study Data And Methods

The primary objectives of this study were to determine whether service use and provider reimbursement patterns changed after citizenship documentation and other eligibility restrictions went into effect in 2006, and how these patterns were affected by the state one-time exception policy. We also aimed to assess whether the new requirements were affecting any subgroups of clients or providers disproportionately.

In particular, we were interested in whether changes in use of services differed for Hispanic and non-Hispanic clients. Because the majority of Oregon’s undocumented population is thought to be Hispanic,14 the citizenship documentation requirements would be expected to have a stronger impact on Hispanic clients if fraudulent use of Medicaid benefits had in fact been occurring before 2006.

Finally, we sought to examine the effects of the teen Social Security number requirement and the restriction on eligibility for insured people on the relevant subgroups.

DATA

The data set for this study consisted of service data from the family planning waiver collected by Oregon’s Public Health Division from 1 May 2005 to 30 April 2008 (eighteen months pre- and post-DRA implementation). Approximately 160 clinics affiliated with the division submit a standard set of data elements for every family planning visit, which number about 200,000 annually.

Data received by the division include the following: patient demographics and reproductive health measures; medical and counseling services provided at the visit; and the visit payment source. The Family Planning Expansion Project is only one of several possible payers. Others include patient fees, either full or partial; the Oregon Health Plan, which is Oregon’s general Medicaid program; and private insurance. At most clinics, uninsured patients who are not eligible for Medicaid are charged on a sliding fee scale, with no charge for those with incomes below 100 percent of the federal poverty level. When visits are coded as “no charge”—which occurs with about 20 percent of all visits—clinics receive no direct reimbursement and must attempt to underwrite the cost of services with other funds, such as Title X grants and county general funds.

METHODS

Using bivariate methods, we analyzed the 425,381 records for Family Planning Expansion Project–billed visits that occurred between May 2005 and April 2008, comparing visit volume and demographic characteristics of clients before and after the Deficit Reduction Act was implemented. Because many of the participating Family Planning Expansion Project clinics also submit data from visits for which reimbursement through the project is not claimed, we had an additional 273,451 non–Family Planning Expansion Project visit records. This made it possible to track clients who may have lost coverage from the program when the Deficit Reduction Act was implemented but who continued to receive services at a participating clinic under a different payment source.

Finally, we conducted subanalyses to assess the impact of the Social Security number and insurance requirements that were implemented along with the citizenship documentation regulations. Teens with Family Planning Expansion Project visits in the eighteen months before the new requirements took effect were divided into two groups: those who had voluntarily provided their Social Security number, a group that constituted about 80 percent of teens, and those who had not.

Similarly, all clients were separated into those with and without insurance coverage for a Family Planning Expansion Project visit in the eighteen months prior to November 2006. We then compared the proportion of each group that returned for a Family Planning Expansion Project visit in the following eighteen months. Where relevant, bivariate tests of significance were conducted.

Results

POPULATION CHARACTERISTICS

Among 698,832 records for family planning visits between May 2005 and April 2008, approximately 61 percent were billed to the Family Planning Expansion Project (Exhibit 1). Almost 30 percent of visits were by clients under age 20, and an additional 34 percent were by clients ages 20–24.

EXHIBIT 1.

Summary Of Visits For Family Planning Analyzed, Oregon Family Planning Expansion Project And Other Payers, May 2005–April 2008

| Total visits

|

Family Planning Expansion Project–billed visits

|

Other visits (not billed to project)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| AGE | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| All ages | 698,832 | 100.0 | 425,381 | 60.9 | 273,451 | 39.1 |

| Under 18 | 99,069 | 14.2 | 59,974 | 14.1 | 39,095 | 14.3 |

| 18–19 | 103,733 | 14.8 | 74,737 | 17.6 | 28,996 | 10.6 |

| 20–24 | 233,996 | 33.5 | 161,501 | 38.0 | 72,495 | 26.5 |

| 25–29 | 129,607 | 18.5 | 69,823 | 16.4 | 59,784 | 21.9 |

| 30+ | 132,427 | 18.9 | 59,346 | 14.0 | 73,081 | 26.7 |

|

| ||||||

| SEX | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Female | 677,945 | 97.0 | 418,278 | 98.3 | 259,667 | 95.0 |

| Male | 20,887 | 3.0 | 7,103 | 1.7 | 13,784 | 5.0 |

| RACE | ||||||

| White | 572,183 | 81.9 | 374,396 | 88.0 | 197,787 | 72.3 |

| African American | 18,079 | 2.6 | 6,456 | 1.5 | 11,623 | 4.3 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 18,380 | 2.6 | 11,263 | 2.6 | 7,117 | 2.6 |

| Other | 25,539 | 3.7 | 14,938 | 3.5 | 10,601 | 3.9 |

| Unknown/not reported | 64,617 | 9.2 | 18,300 | 4.3 | 46,317 | 16.9 |

|

| ||||||

| ETHNICITY | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Hispanic | 143,771 | 20.6 | 37,641 | 8.9 | 106,130 | 38.8 |

| Non-Hispanic | 554,941 | 79.4 | 387,634 | 91.1 | 167,307 | 61.2 |

|

| ||||||

| POVERTY LEVEL | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Under 100% | 516,299 | 73.9 | 318,004 | 74.8 | 198,295 | 72.5 |

| 100%–185% | 157,658 | 22.6 | 105,049 | 24.7 | 52,609 | 19.2 |

| Above 185% | 24,849 | 3.6 | 2,315 | 0.5 | 22,534 | 8.2 |

SOURCE Oregon Family Planning Clinic visit records. NOTES 185 percent of poverty is the upper threshold for Family Planning Expansion Project eligibility, but eligibility is granted for one year, and clients who fluctuate above 185 percent of poverty during that year are not disenrolled. Ethnicity information was missing for 120 visits; race information was missing (in addition to the unknown category) for 34; and poverty-level information was missing for 26.

Although both men and women are eligible for family planning services, 97 percent of visits were by women. Overall, about 21 percent of visits were by Hispanic patients; however, only 9 percent of visits billed to the project were for Hispanic clients, compared to 39 percent of visits not billed to the project. More than 80 percent of visits were by patients describing themselves as white, and almost 74 percent were by clients with below-poverty incomes.

DECLINES IN VISITS

We compared Family Planning Expansion Project visits in the eighteen months after citizenship documentation and other eligibility restrictions were implemented with the number of visits in the eighteen months before implementation. We found that the number of visits declined by 33 percent, versus 10 percent for non–Family Planning Expansion Project visits (Exhibit 2). (Statistically, the p value of this calculation is less than 0.01, which means that it is unlikely to be due to chance.) The drop in Family Planning Expansion Project visits was greater among clients under age eighteen; visits declined by 47 percent among clients under age eighteen, compared with 31 percent among those ages eighteen and older (p value less than 0.01, also unlikely to be due to chance).

EXHIBIT 2.

Family Planning Visits In Oregon, By Time Period And Payer, Oregon Family Planning Expansion Project And Other Providers, May 2005–April 2008

| 18 months pre-DRA

|

18 months post-DRA

|

Change (post-DRA—pre-DRA)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Project

|

Other

|

|||||||

| Project | Other | Project | Other | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| AGE | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| All ages | 254,639 | 143,881 | 170,742 | 129,570 | −83,897 | −32.9 | −14,311 | −9.9 |

| Under 18 | 39,079 | 18,108 | 20,895 | 20,987 | −18,184 | −46.5 | 2,879 | 15.9 |

| 18–19 | 46,032 | 14,926 | 28,705 | 14,070 | −17,327 | −37.6 | −856 | −5.7 |

| 20–24 | 95,527 | 39,933 | 65,974 | 32,562 | −29,553 | −30.9 | −7,371 | −18.5 |

| 25–29 | 39,222 | 32,745 | 30,601 | 27,039 | −8,621 | −22.0 | −5,706 | −17.4 |

| 30+ | 34,779 | 38,169 | 24,567 | 34,912 | −10,212 | −29.4 | −3,257 | −8.5 |

|

| ||||||||

| SEX | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Female | 248,349 | 136,149 | 169,929 | 123,518 | −78,420 | −31.6 | −12,631 | −9.3 |

| Male | 6,290 | 7,732 | 813 | 6,052 | −5,477 | −87.1 | −1,680 | −21.7 |

|

| ||||||||

| RACE | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| White | 224,912 | 104,691 | 149,484 | 93,096 | −75,428 | −33.5 | −11,595 | −11.1 |

| African American | 4,260 | 5,859 | 2,196 | 5,764 | −2,064 | −48.5 | −95 | −1.6 |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 6,699 | 3,834 | 4,564 | 3,283 | −2,135 | −31.9 | −551 | −14.4 |

| Other | 8,953 | 5,933 | 5,985 | 4,668 | −2,968 | −33.2 | −1,265 | −21.3 |

| Unknown/not reported | 9,792 | 23,560 | 8,508 | 22,757 | −1,284 | −13.1 | −803 | −3.4 |

|

| ||||||||

| ETHNICITY | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Hispanic | 22,742 | 55,348 | 14,899 | 50,782 | −7,843 | −34.5 | −4,566 | −8.2 |

| Non-Hispanic | 231,817 | 88,520 | 155,817 | 78,787 | −76,000 | −32.8 | −9,733 | −11.0 |

|

| ||||||||

| POVERTY LEVEL | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Under 100% | 191,413 | 102,476 | 126,591 | 95,819 | −64,822 | −33.9 | −6,657 | −6.5 |

| 100%–185% | 62,164 | 27,524 | 42,885 | 25,085 | −19,279 | −31.0 | −2,439 | −8.9 |

| Above 185% | 1,054 | 13,875 | 1,261 | 8,659 | 207 | 19.6 | −5,216 | −37.6 |

SOURCE Oregon Family Planning Clinic visit records. NOTES 185 percent of poverty is the upper threshold for Family Planning Expansion Project eligibility, but eligibility is granted for one year, and clients who fluctuate above 185 percent of poverty during that year are not disenrolled. Ethnicity information was missing for 120 visits; race information was missing (in addition to the unknown category) for 34; and poverty-level information was missing for 26. All changes for project versus other were significant at p < 0.01. DRA is Deficit Reduction Act.

There was also a disproportionate, statistically significant reduction in usage of services among African Americans (49 percent), compared to other racial minorities (33 percent; p < 0.01, unlikely to be due to chance). Family Planning Expansion Project visits among Hispanic clients declined by 34.5 percent, as compared with a decline of 32.8 percent among non-Hispanics; this small difference was not statistically significant. Visits among those with incomes below 100 percent of poverty declined slightly more than among patients at 100–185 percent of poverty (34 percent versus 31 percent, p < 0.01, also unlikely to be due to chance).

EFFECT OF ONE-TIME VISIT FUNDING

In the eighteen months after DRA citizenship documentation requirements were implemented, 23,470 patients made use of Oregon’s one-time exception visit, representing 11 percent of total Family Planning Expansion Project visits during that time. Without these state-funded exceptions, the overall decline in Family Planning Expansion Project visits would have been 42 percent (as compared to the 33 percent decline that included exceptions). These one-time visits were especially crucial for minors. Visits by teens under age eighteen would have dropped by 57 percent overall, as compared to the 47 percent drop that included the state-funded exceptions.

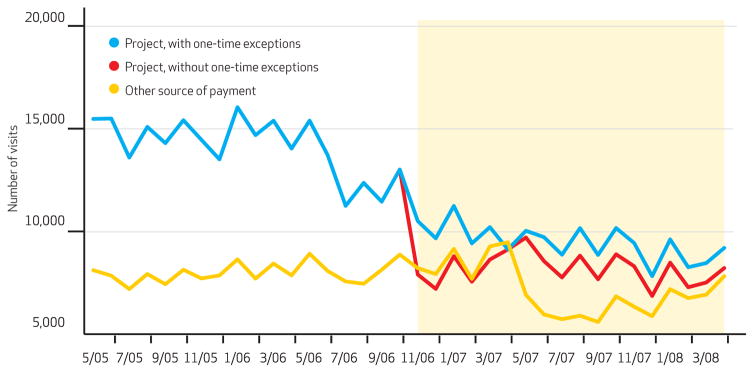

Because of funding limitations, the one-time exception option was temporarily suspended for seven weeks in April and May 2007. As shown in Exhibit 3, the result was that non–Family Planning Expansion Project visits outnumbered Family Planning Expansion Project–paid visits for the month of April 2007.

EXHIBIT 3.

Oregon Family Planning Clinic Visits, By Month And Payment Source, With And Without One-Time Exceptions, May 2005–April 2008

SOURCE Oregon Family Planning Clinic visit records. NOTES Shaded area denotes the implementation period of the Deficit Reduction Act and other federally mandated eligibility changes. In June 2006, citizenship documentation rules were announced. State funding for one-time exception visits was not available from 1 April through 21 May 2007; see text for details. Sample sizes are as follows. Project without one-time exceptions: n = 401, 911. Project with one-time exceptions: n = 425, 381. Other source of payment: n = 273, 451.

About 67 percent of clients with one-time exception visits subsequently confirmed their U.S. citizenship, either by returning voluntarily with the needed documents or by authorizing project staff to acquire electronic or physical copies of their birth certificates. Such visits provided more than $3.4 million in revenue for family planning safety-net provider sites that would otherwise have received almost no direct reimbursement for these crucial services.

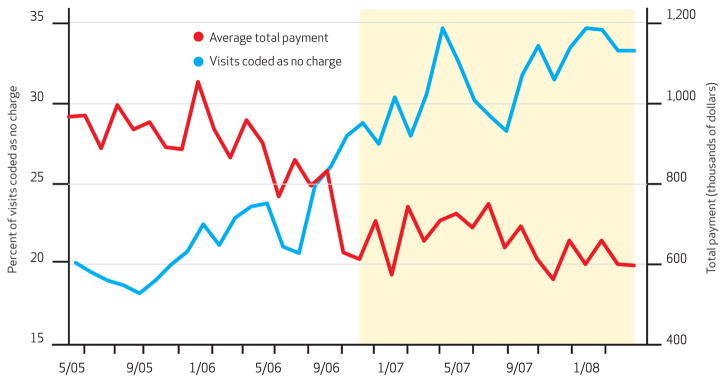

Nevertheless, the proportion of “no-charge” visits at these sites rose from 22 percent in the eighteen months before DRA implementation to 32 percent in the eighteen months afterward (p < 0.01, unlikely to be due to chance). Family Planning Expansion Project payments to these providers dropped by 27 percent, from approximately $895,000 per month to $656,000 per month (p < 0.01, unlikely to be due to chance; Exhibit 4).15

EXHIBIT 4.

Proportion Of Oregon Family Planning Visits Coded As No Charge And Average Total Family Planning Expansion Project Payment At Safety-Net Sites, May 2005–April 2008

SOURCE Oregon Family Planning Clinic visit records. NOTES Blue line (representing percentage of visits coded as no charge) relates to the left-hand y axis. Red line (representing average total payment) relates to the right-hand y axis. Shaded area denotes the implementation period of the Deficit Reduction Act and other federally mandated eligibility changes. In June 2006, citizenship documentation rules were announced. General Family Planning Expansion Project per visit payment was raised to $140 during March–April 2007; however, per visit payment to some high-volume federally qualified health centers declined at the same time. State funding for one-time exception visits was not available from 1 April through 21 May 2007; see text for details.

EFFECTS OF SOCIAL SECURITY NUMBER REQUIREMENT ON TEENS

Exhibit 5 presents the results of subanalyses of Family Planning Expansion Project clients most likely to be affected by the policy changes implemented concurrently with the Deficit Reduction Act. We restricted the analysis to the 40,880 teens who had a Family Planning Expansion Project–paid visit in the eighteen months before the CMS mandated collection of Social Security numbers.

EXHIBIT 5.

Subanalyses Of Groups Affected By Oregon Family Planning Expansion Project Eligibility Restrictions Implemented Along With The Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) Of 2007

| No. of clients with project visit in 18 months pre-DRA | No. of clients with project visit in 18 months post-DRA | Return rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teens (under age 20) | 40,880 | 20,433 | 50.0 | |

| Volunteered Social Security number before required | 30,912 | 16,678 | 54.0 | Ref. |

| Did not volunteer Social Security number | 9,968 | 3,755 | 37.7 | –a |

|

| ||||

| All clients | 121,479 | 52,846 | 43.5 | |

| No insurance payment at pre-DRA visit | 116,365 | 50,618 | 43.5 | Ref. |

| Some insurance payment at pre-DRA visit | 5,114 | 2,228 | 43.6 | |

SOURCE Oregon Family Planning Clinic visit records.

Return rate is significantly different from referent group at p < 0.01.

We found that teens who were not able to provide their Social Security numbers prior to the mandatory requirement were significantly less likely than their peers to return for a Family Planning Expansion Project–paid visit after the new requirement went into effect.

No such differences were found for Family Planning Expansion Project clients who had another insurance payment source prior to November 2006. When compared with the vast majority of clients who reported no outside insurance source prior to the Deficit Reduction Act (Exhibit 5), clients with outside insurance returned at an equal rate in the eighteen months following implementation of the CMS rule denying Family Planning Expansion Project eligibility to people with creditable insurance.

Discussion

The implementation of the DRA citizenship documentation requirements was directly associated with a sharp drop in use of Oregon’s Family Planning Expansion Project services. Use of services dropped most among clients under age eighteen. This is a troubling finding in light of recent evidence that teen pregnancy rates are beginning to plateau or creep upward after a decade or more of declines.16

A provision in the Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA) of 2009 allowing states to verify Social Security numbers in lieu of collecting citizenship documentation may be an option for mitigating the decline in use of family planning services.17 However, the disproportionately low return rate among Family Planning Expansion Project teen clients who did not disclose their Social Security numbers before doing so became a condition of enrollment suggests that even the requirement to provide Social Security numbers may be an insurmountable burden for teens seeking confidential services.

A second policy-relevant finding was the absence of a statistically significant difference in changes in usage by ethnicity (Hispanic versus non-Hispanic). Estimates suggest that the bulk of undocumented U.S. residents are Hispanic.14 This finding thus casts doubt on the assertion that the citizenship documentation requirements were necessary to combat fraudulent use of Medicaid benefits by noncitizens.18

Rather, the Deficit Reduction Act was associated with precipitous declines in provider reimbursement, in concert with the drop in use of Family Planning Expansion Project services and the increase in no-charge visits. One-time exception visits, funded by the state, appeared to have mitigated the law’s effects on clients’ access to services and may have also provided some partial stabilization of reimbursement for safety-net providers facing large numbers of clients with no payment source.

Although the drop in use of Family Planning Expansion Project services resulted in lower federal spending in the short term, it is possible that these savings will result in more costly health care needs over the longer term. For families forced to forgo family planning care or to resort to less reliable methods of birth control, it is likely that pregnancy rates increased. Given that pregnancy-related care is much more expensive than providing contraception, even a relatively small increase in the number of pregnancies among Oregon’s Family Planning Expansion Project population will require large increases in federal and state health care spending.

Project-eligible clients also had to delay or forgo other essential services, such as screening for cervical cancer and sexually transmitted infections. Delayed diagnoses and treatment of such medical conditions could result in increased rates or severity of illness.

Additional studies are needed to assess the extent to which a loss of Family Planning Expansion Project coverage may have affected former clients’ access to family planning services, effective use of contraception, and use of screening and treatment services for preventable medical conditions.

In addition to directly affecting individuals, the decline in Family Planning Expansion Project usage and reimbursement appeared to strain an already vulnerable system of safety-net providers, which could indirectly compromise their ability to provide other services. There is anecdotal evidence that the loss of revenue from the Family Planning Expansion Project has forced Oregon’s Medicaid family planning service providers to reduce hours, eliminate walk-in appointments, cut staffing levels, or even close down. These changes jeopardize access to care for everyone. If Medicaid clients are forced to go hospital emergency departments because they are finding it more difficult to get services from their safety-net clinic, both federal and state governments will shoulder increased costs.

Limitations

These findings must be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, the analytic methods show an association but cannot definitively demonstrate a causal relationship between the implementation of citizenship documentation requirements and the decline in use of waiver services. Nevertheless, the timing and scale of the observed decline are significant.

Potential alternative or additional explanations for the changes in Family Planning Expansion Project use include concurrent pressures on the delivery system that may have reduced the availability of services.

It is also unclear whether clients who lost Family Planning Expansion Project coverage were able to obtain services outside the network of providers participating in the program or whether such clients chose to substitute over-the-counter methods of contraception.

Survey and qualitative research with both the Family Planning Expansion Project provider and client populations would help clarify these unknowns. The findings in this paper represent the experience of one family planning waiver program in one state; they might not be applicable to other programs or contexts. In particular, the simplicity of Oregon’s Family Planning Expansion Project enrollment process prior to the DRA implementation and the waiver renewal in 2006 were unusual among Medicaid programs. However, California’s family planning waiver had a similar operation, and the state faced threats of losing federal approval for its waiver as a result of delays in implementing the citizenship documentation requirements.19

Finally, because family planning providers in Oregon have up to one year from the date of service to submit reimbursement claims, and the data presented here were obtained in February 2009, they cannot be considered complete. However, more than 99 percent of claims are submitted within ten months of the date of service, so additional data would be unlikely to change the findings substantially.

Conclusion

Medicaid citizenship documentation requirements have been burdensome for Oregon Family Planning Expansion Project patients and costly for health care providers who participate in the program. The results have been reduced access to family planning services and preventive health care for thousands of Oregon families and greater strain on the safety-net system. The policy has been most harmful for the youngest clients and for African Americans; no significant differential was observed between Hispanic and non-Hispanic clients. If the Deficit Reduction Act does achieve its stated aim of reducing the federal budget deficit, evidence from the Family Planning Expansion Project suggests that it will do so by delaying or denying care for many people who are truly eligible and by shifting costs to state- and local-level providers.

Acknowledgments

Jennifer DeVoe’s time on this project was partially supported by Grant no. 1-K08-HS16181 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and by the Oregon Health and Science University Department of Family Medicine Research Division. The authors thank the Oregon Health Research and Evaluation Collaborative and the Family Planning Expansion Project Workgroup. They also thank David Dowler, Nurit Fischler, and Collette Young for their contributions.

Footnotes

An earlier version of this analysis was presented at the 2008 AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting in Washington, D.C.

Contributor Information

Lisa Angus, Email: lisa.angus @state.or.us, The time of this research, a policy and research analyst at the Oregon Public Health Division in Portland.

Jennifer DeVoe, Assistant professor of family medicine at the Oregon Health and Science University in Portland.

NOTES

- 1.Guttmacher Institute. State Policies in Brief Series. New York (NY): Guttmacher Institute; 2010. Feb, State Medicaid family planning eligibility expansions [Internet] [cited 2010 Feb 17]. Available from: http://www.alanguttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_SMFPE.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson Gold R. Breaking new ground: ingenuity and innovation in Medicaid family planning expansions. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2008;11(2):7–12. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benson Gold R, Richards CL. Issue Brief. Menlo Park (CA): Kaiser Family Foundation; 2007. Oct, Medicaid’s role in family planning [Internet] [cited 2009 Mar 30]. Available from: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/IB_medicaidFP.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deficit Reduction Act of 2005, PL 109–171, 120 Stat. 4 (2006 Feb 8).

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector General. Self-declaration of US citizenship for Medicaid [Internet] Washington (DC): OIG; 2005. Jul, [cited 2008 Jul 3]. Available from: http://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-03-00190.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicaid program; citizenship documentation requirements. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2007 Jul 13;72(134):38662–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haber SG, Khatutsky G, Mitchell JB. Covering uninsured adults through Medicaid: lessons from the Oregon Health Plan. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;22(2):119–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gauthier AK, Gates VS, Helms WD. State coverage expansions: learning from research and practice. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(1):33–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kronebusch K, Elbel B. Simplifying children’s Medicaid and SCHIP. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(3):233–46. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross DC, Cox L, Marks C. Resuming the path to health coverage for children and parents: a 50-state update on eligibility rules, enrollment and renewal procedures, and cost-sharing practices in Medicaid and SCHIP in 2006 [Internet] Washington (DC): Kaiser Family Foundation; 2007. Jan, [cited 2007 Apr 30]. Available from: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/7608.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Government Accountability Office. States reported that citizenship documentation requirement resulted in enrollment declines for eligible citizens and posed administrative burdens [Internet] Washington (DC): GAO; 2007. Jun, [cited 2007 Aug 17]. Available from: http://www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?GAO-07-889. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Smith V, Gifford K, Ellis E, Rudowitz R, O’Malley M, Marks C. Headed for a crunch: an update on Medicaid spending, coverage, and policy heading into an economic downturn: results from a 50-state Medicaid budget survey for state fiscal years 2008 and 2009 [Internet] Washington (DC): Kaiser Family Foundation; 2008. Sep, [cited 2008 Oct 19]. Available from: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/7815.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benson Gold R, Sonfield A, Richards CL, Frost JJ. Next steps for America’s family planning program: leveraging the potential of Medicaid and Title X in an evolving healthcare system [Internet] New York (NY): Guttmacher Institute; 2009. [cited 2010 Feb 17]. Available from: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/NextSteps.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Passel JS, Cohn D. A portrait of unauthorized immigrants in the United States. Washington (DC): Pew Hispanic Center; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Some of this decline is attributable to unrelated Family Planning Expansion Project reimbursement changes in March and April 2007, as a result of which payments to federally qualified health centers declined by an average of about $35 per visit.

- 16.Guttmacher Institute. US teenage pregnancies, births, and abortions: national and state trends and trends by race and ethnicity [Internet] New York (NY): Guttmacher Institute; c2010. [updated 2010 Jan 26; cited 2010 Mar 2]. Available from: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/USTPtrends.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured [Internet] Fact Sheet. Washington (DC): Kaiser Family Foundation; c2009–10. Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA) [Internet] [updated 2009 Feb 12; cited 2009 Feb 17]. Available from: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/7863.cfm. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levine S, Otto M. Washington Post. 2006. Jun 30, Medicaid rule called a threat to millions; proof of citizenship needed for benefits; p. A1. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rau J. Los Angeles Times. 2008. Oct 3, Dispute imperils California family planning program for the poor; p. B1. [Google Scholar]