Abstract

Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are important in tumor angiogenesis. Stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) and its receptor C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) are key in stem cell homing. Melittin, a component of bee venom, exerts antitumor activity, however, the underlying mechanisms remain to be elucidated. The present study aimed to assess the effects of melittin on EPCs and angiogenesis in a mouse model of osteosarcoma. UMR-106 cells and EPCs were treated with various concentrations of melittin and cell viability was determined using the MTT assay. EPC adherence, migration and tube forming ability were assessed. Furthermore, SDF-1α, AKT and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 expression levels were detected by western blotting. Nude mice were inoculated with UMR-106 cells to establish an osteosarcoma mouse model. The tumors were injected with melittin, and its effects were assessed by immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence. Melittin decreased the viability of UMR-106 cells and EPCs. In addition, it decreased EPC adhesion, migration and tube formation when compared with control and SDF-1α-treated cells. Melittin decreased the expression of phosphorylated (p)-AKT, p-ERK1/2, SDF-1α and CXCR4 in UMR-106 cells and EPCs when compared with the control. The proportions of cluster of differentiation (CD)34/CD133 double-positive cells were 16.4±10.4% in the control, and 7.0±4.4, 2.9±1.2 and 1.3±0.3% in tumors treated with 160, 320 and 640 µg/kg melittin per day, respectively (P<0.05). At 11 days, melittin reduced the tumor size when compared with that of the control (control, 4.8±1.3 cm3; melittin, 3.2±0.6, 2.6±0.5, and 2.0±0.2 cm3 for 160, 320 and 640 µg/kg, respectively; all P<0.05). Melittin decreased the microvessel density, and SDF-1α and CXCR4 protein expression levels in the tumors. Melittin may decrease the effect of osteosarcoma on EPC-mediated angiogenesis, possibly via inhibition of the SDF-1α/CXCR4 signaling pathway.

Keywords: melittin, osteosarcoma, stromal cell-derived factor-1α, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4, endothelial progenitor cells, angiogenesis

Introduction

Osteosarcomas are malignant tumors arising from mesenchymal cells (1). They are the second most common primary bone malignancy, after multiple myeloma, and represent 15% of all bone tumors (1). Men are more commonly afflicted than women (ratio, 1.5:1) and 75% of patients are aged 15–25 years (1). Risk factors include retinoblastoma, ionizing radiation and germline p53 mutations (1). Treatment strategies include combinations of surgery, chemotherapy and radiation; with chemotherapy increasing the 2- and 25-year survival rates (1–3). Osteosarcomas predominantly metastasize to the lungs, liver and brain (1), and overall survival is ~56% at 5 years and ~52% at 10 years (4). Angiogenesis is important in the progression of malignant tumors, evolution and metastasis (5,6). Endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) are pluripotent stem cells that have the potential to differentiate into mature endothelial cells (7). They possess a strong capacity for multiplication and colony formation (7). EPCs are present in the bone marrow and in the peripheral blood (derived from the bone marrow) (8). Peripheral blood EPCs are important in active revascularization by differentiating into mature endothelial cells to form new blood vessels (9,10). Mukai et al (11) used an in vivo 3D model using Matrigel to demonstrate that EPCs form tubular structures. In addition, previous studies have indicated that osteosarcoma cells have the potential to enhance angiogenesis (12–14).

Previous studies have demonstrated that the stromal cell-derived factor-1α (SDF-1α) and its receptor, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4 (CXCR4) are important in stem cell homing and tumor metastasis (15,16). The SDF-1α/CXCR4 signal transduction pathway is also important in tumor angiogenesis (17,18). SDF-1α is expressed in hypoxic tissues, such as tumors and damaged tissues, and is the primary chemokine that mobilizes pro-angiogenic cells (19). CXCR4 is expressed on EPCs, where it mediates the specific homing of EPCs to hypoxic tissues to initiate angiogenesis (19).

Melittin is the main compound found in bee venom (20). Modern pharmacology studies have observed that melittin exerts various antitumor effects by inhibiting tumor cell growth (21,22), promoting tumor cell apoptosis (23–25), and inhibiting tumor angiogenesis (26) and migration (27,28). However, the effect of melittin on EPCs remains unknown.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine the effects of melittin on EPCs and on osteosarcoma-induced angiogenesis, and to investigate the underlying mechanisms of these effects. The current study hypothesized that melittin exerts its effects by modulating SDF-1α/CXCR4 signaling.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male BALB/c nu/nu nude mice (n=24), aged 4–6 weeks and weighing 18–20 g, were bought from Shanghai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Mice were housed in separate cages at the Animal Experiment Centre of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Guangxi, China) in a specific pathogen-free environment and were maintained under a 12-h light/dark cycle, with access to food and water ad libitum. Mice were acclimatized to their environment for one week prior to experiments. All procedures and animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

Cell culture

The UMR-106 rat osteoblastic osteosarcoma cell line was obtained from the Institute of Orthopedics of the Fourth Military Medical University (Xi'an, China). UMR-106 cells were cultured in Gibco Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with Gibco 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Isolation, culture and identification of EPCs

EPCs were obtained using previously described methods (29,30). The femur and tibia were removed under sterile conditions. Metaphyseal bone forceps were used to remove the bone ends to expose the medullary cavity. M199 medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was injected from one end of the bone, and the bone marrow washing out was collected on the other end. Mononuclear cells were isolated by density gradient centrifugation. Following two washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Labest Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), mononuclear cells were suspended in M199 medium with 10% FBS, 10 ng/ml vascular endothelial growth factor (Prospec-Tany TechnoGene Ltd., East Brunswick, NJ, USA) and 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (Prospec-Tany TechnoGene Ltd.). Mononuclear cells were inoculated in Petri dishes pre-coated with rat fibronectin (RFN; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and incubated at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The medium was replaced after 4 days, and subsequently every 3 days. Cells at passage 3 were stained with rabbit anti-rat cluster of differentiation (CD)34 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), rabbit anti-rat CD133 (Abcam), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (Ig)G (Yingrun Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Changsha, China) and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Yingrun Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). The double-positive expression of CD34 and CD133, indicating EPCs (31,32), was observed using a BX51 fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Non-specific anti-rat antibodies served as an isotype control.

Effect of melittin on cell viability

UMR-106 cells and EPCs (1,000 cells/well) were plated in 96-well plates for 24 h. Blank control wells contained medium without cells. Following 24 h, the culture medium was replaced with DMEM containing 5% FBS to synchronize the cells for 6 h. The cells were treated with various concentrations (0, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 µg/ml dissolved in 0.9% saline) of melittin (>98% purity; Sigma-Aldrich) for 48 h. MTT (10 µl; 5 mg/ml; Ameresco, Inc., Framingham, MA, USA) was added and the incubation continued for 4 h. The medium containing MTT was discarded, 200 µl dimethyl sulfoxide (Haoran Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) was added and the plates were agitated for 10 min. A Model 500 Microplate Reader (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA) was used to measure the optical density (OD) at a wavelength of 490 nm. The percentage of cell viability was calculated according to the following formula: Cell viability (%) = (average OD of the experimental group)/(average OD of the control group) × 100, where average is the optical density obtained from three independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Adhesion of EPCs

EPCs (1×105 cells/well) were plated in 12-well RFN-coated plates. EPCs were divided into four groups: Control (untreated); 10 ng/ml SDF-1α (Prospec-Tany TechnoGene Ltd.); 1 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α; and 3 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α. At these concentrations melittin was determined to have low toxicity in preliminary experiments. Following 2 h, the culture medium was discarded, the EPCs were washed twice with PBS, and fixed with 95% alcohol for 30 min. Cells were washed twice with PBS, stained with 0.1% crystal violet (200 µl; Haoran Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 15 min and washed twice with PBS. The plates were dried and observed using the IX70 inverted optical microscope (Olympus Corporation). Images of five randomly selected fields were captured (magnification, ×100). Adherent EPCs were counted by two independent observers who were blinded to the experimental conditions.

Migration of EPCs

The migration ability of EPCs was assessed using 24-well Transwell plates (pore size, 8 µm; Corning Incorporated, Corning, NY, USA). M199 medium containing 2% FBS (control) and the treatments (10 ng/ml SDF-1α; 1 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α; and 3 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α) was placed in the lower chamber and served as a chemoattractant. M199 culture medium (200 µl) containing 1×105 EPCs was placed in the upper chamber. Following 6 h, the cells on the upper surface of the filter were removed by gently wiping with a cotton swab. The cells that had migrated were fixed with 95% alcohol for 30 min and stained with 0.1% crystal violet. Migrated cells were visualized using the inverted optical microscope. Images of five randomly selected fields were captured (magnification, ×100) and the number of migrated cells was counted by two independent observers blinded to the experimental conditions.

Tube formation assay

Matrigel (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) was added to 48-well plates to a total volume of 120 µl/well. Wells were divided into four groups: Control (untreated); 10 ng/ml SDF-1α, 1 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α; and 3 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α. Gel was allowed to polymerize for 30 min at 37°C and EPCs (5×104 cells/well) were inoculated on the Matrigel. Following 23 h of incubation, at 37°C in 5% CO2, the area covered by the tube network was determined using the inverted optical microscope (magnification, ×100).

Western blot analysis of CXCR4, SDF-1α, phosphorylated (p)-AKT, AKT, p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2 in UMR-106 cells and EPCs

Cells were lysed using a total protein lysis buffer (Shanghai Pufei Biotech Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) and centrifuged at 8000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Protein concentrations were determined using a BCA kit (Shanghai Pufei Biotech Co., Ltd.). Equal quantities of proteins were isolated by 8% SDS-PAGE (run at 110 Volts for 90 min) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Membranes were blocked for 2 h in 5% dried milk at room temperature, and washed in Tris-buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBST) three times for 10 min each time. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies as follows: rabbit polyclonal CXCR4 (1:200; Abcam; cat. no. ab74012), SDF-1α (1:200; Yuan Mu Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China; cat. no YM-XQ4938P); p-AKT (1:200; Abcam; cat. no. ab38449); AKT (1:200; Abcam; cat. no. ab79360); p-ERK1/2 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; cat. no. sc-101760); ERK1/2 (1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.; cat. no. sc-292838); mouse monoclonal β-actin (1:200; Abcam; cat. no. ab6276). Membranes were washed with TBST three times for 10 min each time, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with polyclonal HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000; GenScript Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China; cat. no. A00098) and polyclonal HRP-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (1:1,000; Wuhan Boster Biological Technology, Ltd., Wuhan, China; cat. no. BA1050) secondary antibodies. Following three further washes in TBST, for 10 min each time, membranes that contained the relevant protein bands were observed by enhanced chemiluminescence using the BeyoECL Plus hypersensitive ECL chemiluminescence kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Nanjing, China). Images were captured and analyzed.

UMR-106 osteosarcoma xenograft mouse model

The mouse model of osteosarcoma was established using a previously described method (33). Male nude mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of 1% sodium pentobarbital (70 mg/kg) and inoculated with UMR-106 cells (2×105/20 µl) in the left hind leg tibial plateau. Intra-tumor multipoint local injections were administered when the tumors grew to ~0.5×0.5 cm. In the negative control group (n=6), tumors were injected with normal saline in a total volume of 200 µl, once a day. For the low, moderate and high melittin groups (n=6/group), mice received a local injection of 160, 320 and 640 µg/kg melittin, respectively, once a day, for 5 days. The mice were treated for two 5-day periods with one day between the two periods. Following each injection, the major and minor axes of the tumors were measured. The size of the tumors was calculated using the following formula: Tumor volume (mm3) = major axis × minor axis2/2 (34). Mice were sacrificed on the day after the second period of treatment.

Immunofluorescence staining for CD34 and CD133

Mouse tumor tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutralized formalin (Haoran Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), dehydrated, embedded in paraffin and sliced into 4-µm sections. The sections were dewaxed, endogenous peroxidase was neutralized with 3% H2O2 and antigen retrieval was performed by incubating the sections in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0; Labest Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) for 40 min at 92°C, and in normal goat serum (Wuhan Amyjet Scientific Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China) for 20 min at 37°C. The sections were incubated with rabbit polyclonal CD34 (1:100; Abcam; cat. no. ab185732), rabbit polyclonal CD133 (1:100; Otwo Biotech Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China; cat. no. 251149), FITC-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500; Walan Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China; cat. no. AS011) and Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500; Sanying Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuhan, China; cat. no. 00009-2) in the dark, at 37°C for 30 min. Sections were washed 3 times in PBS, glycerophosphoric acid buffer solution (Labest Biotechnology Co., Ltd.) was added, and observed under IX70 inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus Corporation). The double-positive area was quantified as the percentage of the total area using Image Pro Plus software, version 5.0 (Media Cybernetics, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA). The quantity of EPCs was evaluated.

Immunohistochemical detection of CXCR4, SDF-1α and microvessel density (MVD)

Expression levels of CD105, CXCR4 and SDF-1α were detected by immunohistochemistry. Sections were dewaxed, endogenous peroxidase was neutralized with 3% H2O2 and antigen retrieval was conducted by incubating the sections in 0.01 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 40 min at 92°C, and in normal goat serum for 20 min at 37°C. Sections were incubated with rabbit polyclonal CD105 (1:200; Abcam; cat. no. ab107595), rabbit polyclonal CXCR4 (1:200) and rabbit polyclonal SDF-1α (1:200) overnight at 4°C. The sections were washed 3 times in PBS and incubated with polyclonal HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1,000) secondary antibody at 37°C. Sections were revealed by 3,3′-diaminobenzadine (DAB) (Haoran Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), counterstained with hematoxylin (Haoran Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), dehydrated and mounted with neutral balsam (Noble Ryder Beijing Science and Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). The positive areas were quantified as the percentage of the total area using Image Pro Plus 5.0. A negative control was obtained using PBS rather than a primary antibody.

MVD

MVD was assessed by immunohistochemistry according to the method by Weidner et al (35) using CD105-positive cells. Each EPC or cluster of EPCs that could be separated from surrounding vessels, tumor cells and other connective tissues were counted as a single capillary. As long as the microvascular structure was not continuous, the branch structure was also counted as a vessel. Capillaries were not assessed according to the presence of erythrocytes or by the presence of a lumen. Capillaries with a lumen area >8 erythrocytes in diameter and with a thick muscular layer were not counted, furthermore, capillaries in fibrotic areas and in areas with scarce tumor cells were not counted. The five areas with the highest MVD were photographed under an inverted optical microscope (magnification, ×400). MVD was evaluated by two independent observers blinded to the experimental conditions. The average value of the five areas (mean ± standard deviation) was taken as the MVD value of the tumor.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are presented as means ± standard deviation from three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance was conducted with the least significant difference for post hoc tests. SPSS 15.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

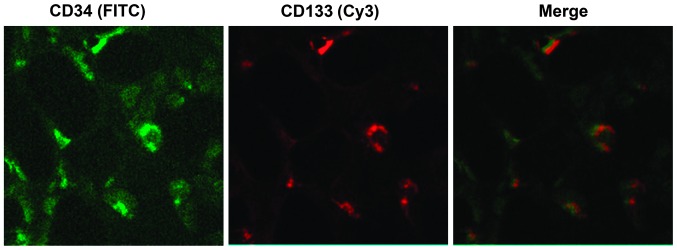

EPCs were successfully isolated

As presented in Fig. 1, cells with a green fluorescence signal are CD34-positive cells, and cells with a red fluorescence signal are CD133-positive cells. The merge indicates the CD34/CD133 double-positive cells, which demonstrate the EPCs (31,32).

Figure 1.

Identification of endothelial progenitor cells using the cell surface markers, CD34 and CD133. Expression of CD34 (green, FITC) and CD133 (red, Cy3) was detected by fluorescence microscopy (magnification, ×200). The merge demonstrated the CD34/CD133 double-positive cells; endothelial progenitor cells. CD, cluster of differentiation; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; Cy3, cyanine 3.

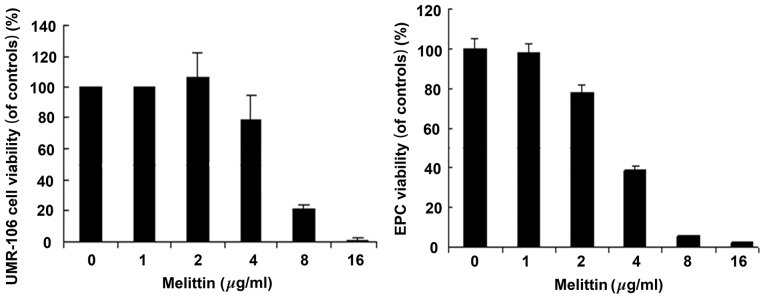

Melittin decreases the viability of UMR-106 cells and EPCs

Fig. 2 demonstrates that melittin decreased the viability of UMR-106 cells and EPCs in a dose-dependent manner. The half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) values for UMR-106 cells and EPCs were 6.33 and 4.51 µg/ml, respectively.

Figure 2.

Effects of melittin on the viability of UMR-106 cells and EPCs. UMR-106 cells and EPCs were treated with 0, 1, 2, 4, 8 and 16 µg/ml melittin for 48 h. Cell viability was determined by MTT. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation. *P<0.05 vs. control. EPC, endothelial progenitor cell.

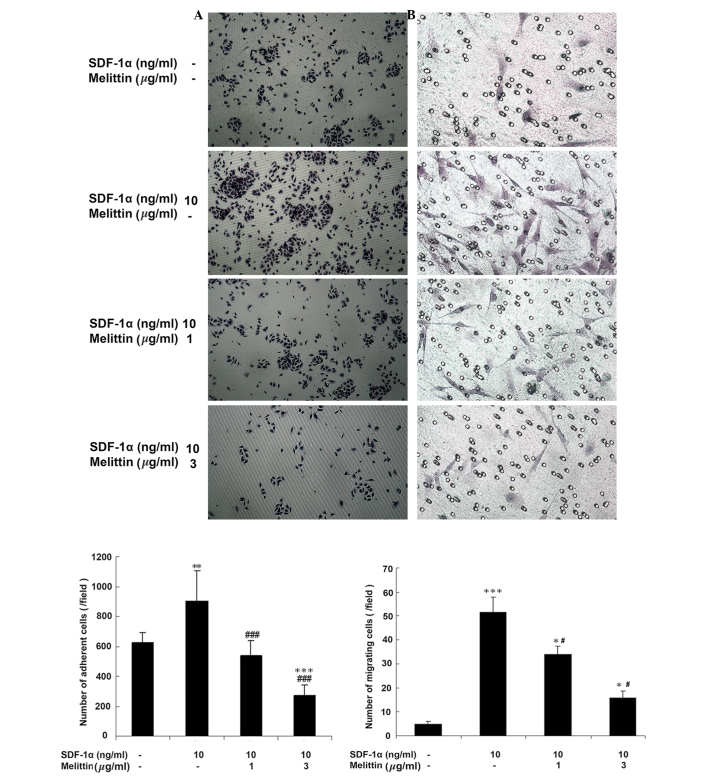

SDF-1α increases EPCs adhesion, which is decreased by melittin

Fig. 3A indicates that melittin decreased the adherence of EPCs, which was facilitated by SDF-1α. The number of adherent cells was 620.8±19.6 in the control, 900.6±16.2 in cells treated with 10 ng/ml SDF-1α (P<0.01 vs. control), 532.4±5.6 in cells treated with 1 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α (P<0.001 vs. SDF-1α) and 270.2±1.5 in cells treated with 3 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α (P<0.001 vs. control; P<0.001 vs. SDF-1α).

Figure 3.

Effects of SDF-1α and melittin on EPC adhesion and migration. EPCs were divided into four groups: Control (untreated), 10 ng/ml SDF-1α, 1 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α, and 3 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α. (A) Following 2 h of treatment, adhesion of EPCs was determined (magnification, ×100). (B) Following 6 h of treatment, migration of EPCs was determined by Transwell migration assay (magnification, ×200). Data are presented as means ± standard deviation. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. controls; #P<0.05, ###P<0.001 vs. SDF-1α. SDF-1α, stromal cell-derived factor-1α; EPC, endothelial progenitor cell.

SDF-1α increases EPCs migration, which is decreased by melittin

Fig. 3B demonstrates that melittin decreased the number of migrating EPCs, which was facilitated by SDF-1α. The number of cells that had migrated was 4.8±6.4 in the control, 51.5±3.5 in cells treated with 10 ng/ml SDF-1α (P<0.001 vs. control), 34.1±3.0 in cells treated with 1 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α (P<0.05 vs. the control; P<0.05 vs. SDF-1α) and 15.7±1.8 in cells treated with 3 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α (P<0.05 vs. control; P<0.05 vs. SDF-1α).

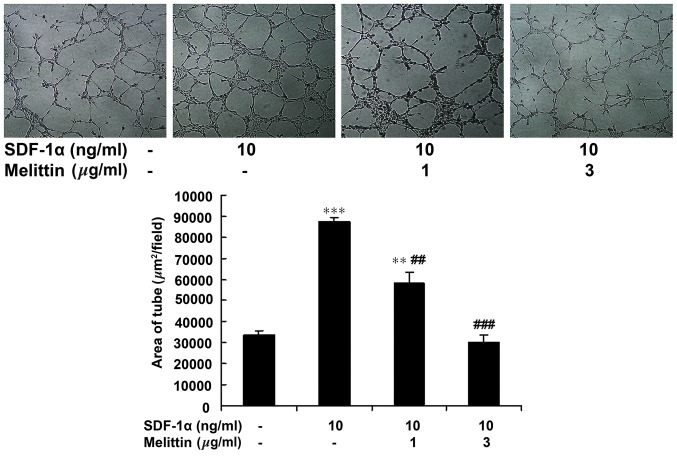

SDF-1α increases EPCs tube formation, which is decreased by melittin

Fig. 4 indicates that melittin decreased the tube forming ability of EPCs, which was facilitated by SDF-1α. The area of the tubes was 33,806±1,703 µm2/field in the control, 87,504±2,102 µm2/field in cells treated with 10 ng/ml SDF-1α (P<0.001 vs. control), 58,401±4,857 µm2/field in cells treated with 1 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α (P<0.01 vs. control; P<0.01 vs. SDF-1α) and 30,165±3,430 in cells treated with 3 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α (P<0.001 vs. SDF-1α).

Figure 4.

Effect of SDF-1α and melittin on EPC tube formation ability. EPCs were divided into four groups: Control (untreated), 10 ng/ml SDF-1α, 1 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α, and 3 µg/ml melittin + 10 ng/ml SDF-1α. Following 23 h of treatment, tube formation was determined (magnification, ×100). Data are presented as means ± standard deviation. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. controls; ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs. SDF-1α. SDF-1α, stromal cell-derived factor-1α; EPC, endothelial progenitor cell.

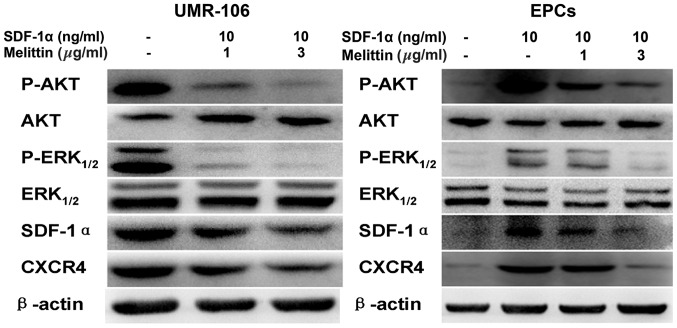

Melittin decreased the protein expression levels of p-AKT, p-ERK1/2, SDF-1α and CDCR4 in the UMR-106 cells and EPCs

Fig. 5 presents the western blots of CXCR4, SDF-1α, p-AKT, AKT, p-ERK1/2, and ERK1/2 expression in UMR-106 cells and EPCs following treatment with SDF-1α and melittin. Compared with the control, melittin decreased the expression of p-AKT, p-ERK1/2, SDF-1α and CXCR4 in UMR-106 cells and EPCs.

Figure 5.

Effects of SDF-1α and melittin on the expressions of p-AKT, AKT, p-ERK1/2, ERK1/2, SDF-1α, CXCR4 in UMR-106 cells and EPCs. Protein expression was determined by western blot analysis and β-actin served as an internal control. SDF-1α, stromal cell-derived factor-1α; EPC, endothelial progenitor cell; p, phosphorylated; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; CXCR4, C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4.

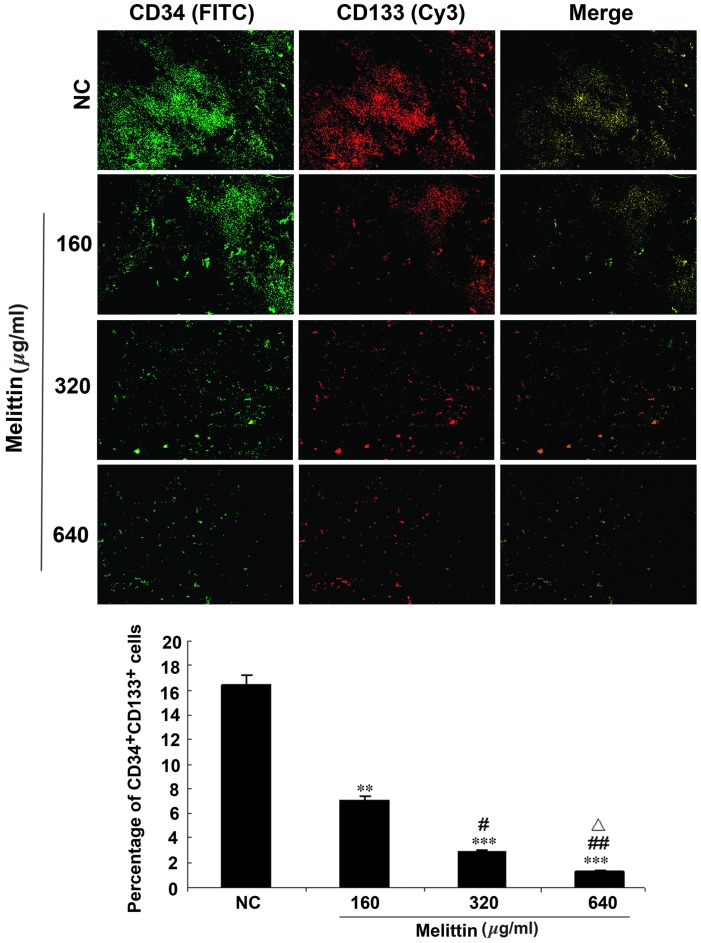

Melittin decreases the proportion of CD34/CD133 cells in an osteosarcoma xenograft mouse model

A mouse model of osteosarcoma was established using UMR-106 cells and tumors were injected with various doses of melittin. Intra-tumor EPCs were detected by immunofluorescence (Fig. 6). The proportion of CD34/CD133 double-positive cells was 16.4±10.4% in the control, 7.0±4.4% in tumors treated with 160 µg/kg melittin per day (P<0.01 vs. control), 2.9±1.2% in tumors treated with 320 µg/kg melittin per day (P<0.001 vs. control and P<0.05 vs. 160 µg/kg melittin), and 1.3±0.3% in tumors treated with 640 µg/kg melittin per day (P<0.001 vs. control, P<0.01 vs. 160 µg/kg melittin, and P<0.05 vs. 320 µg/kg melittin).

Figure 6.

Effects of melittin on the proportion of CD34/CD133 double-positive cells in the mouse model of UMR 106 osteosarcoma. Intra-tumor multipoint local injections were administered when the tumors grew to ~0.5×0.5 cm. For the NC group, tumors were treated with a local injection of normal saline (total volume, 200 µl) once a day. Tumors were treated with local injections of 160, 320 or 640 µg/kg melittin, once a day, for a treatment period of 5 days. Mice were treated for two 5-day periods, with one day between the two periods. CD34 (green, FITC) and CD133 (red, Cy3) expression in the tumor tissue samples was detected using fluorescence microscopy (magnification, ×100). The proportions of CD34/CD133 double-positive cells are presented as means ± standard deviation (n=6/group). **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. NC; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 vs. 160 µg/kg melittin; △P<0.05 vs. 320 µg/kg melittin. CD, cluster of differentiation; NC, negative control; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; Cy3, cyanine 3.

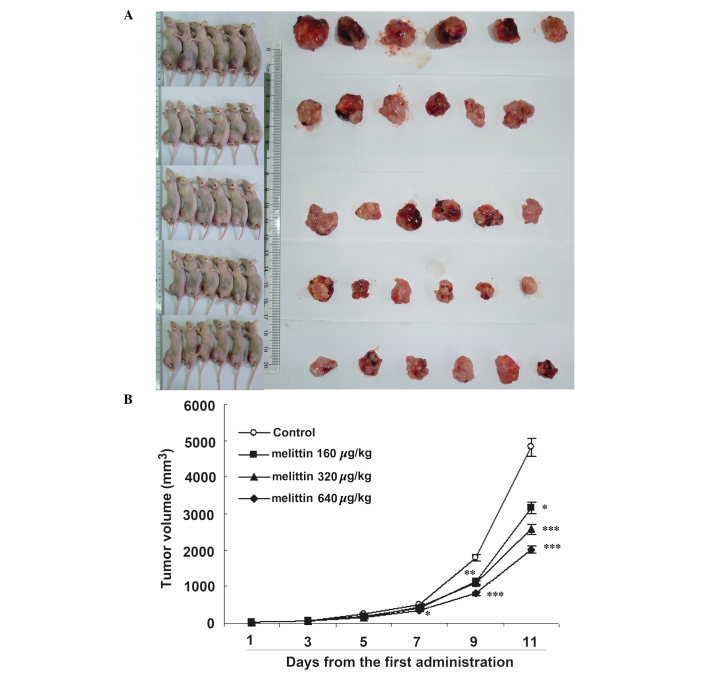

Melittin decreases tumor size in vivo

Fig. 7 demonstrates that melittin decreased osteosarcoma growth. Curves began to separate at 7 days following onset of treatment. At 11 days, the three doses of melittin resulted in smaller tumors compared with the control (control, 4.8±1.3 cm3; 160 µg/kg melittin, 3.2±0.6 cm3; 320 µg/kg melittin, 2.6±0.5 cm3; and 640 µg/kg melittin, 2.0±0.2 cm3; all P<0.05 vs. the control).

Figure 7.

Effects of melittin on tumor volume in the UMR-106 osteosarcoma-bearing mouse model. (A) Gross appearance of tumors harvested from the mice. (B) Tumor volume was determined every other day from the first administration of melittin, and presented as means ± standard deviation (n=6/group). *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 vs. controls.

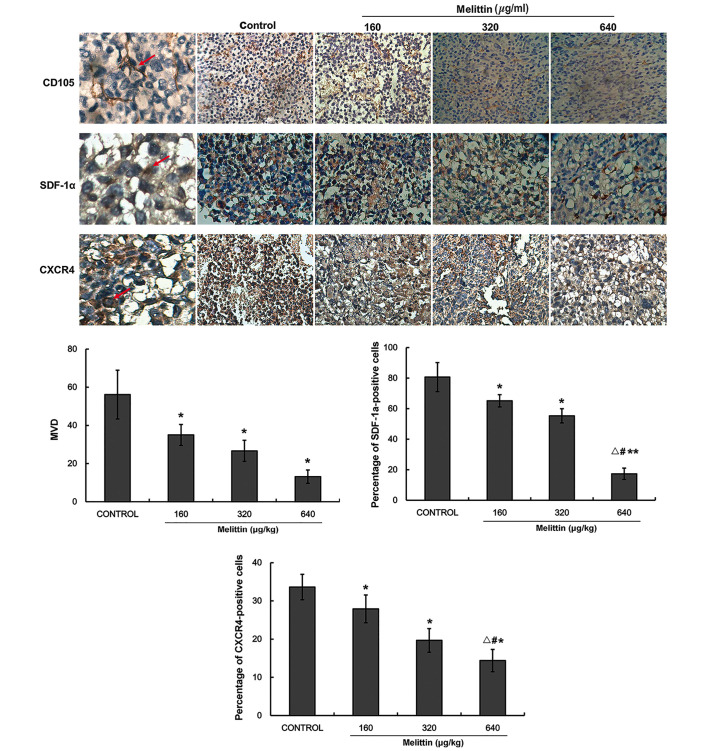

Melittin decreases MDV, CXCR4 and SDF-1α protein expression levels

CD105 immunohistochemistry was performed to determine MVD. Fig. 8 indicates that MVD decreased with melittin administration in a dose-dependent manner (control, 56.2±12.8; 160 µg/kg melittin, 35.0±5.5; 320 µg/kg melittin, 26.7±5.5; and 640 µg/kg melittin, 13.2±3.5 cm3; all P<0.05 vs. control).

Figure 8.

Effect of melittin on CD105, SDF-1α and CXCR4 protein expression levels in the tumors of the UMR-106 osteosarcoma xenograft mouse model. CD105, SDF-1α and CXCR4 protein expression levels were determined by immunohistochemistry. CD105 was used to assess MVD (magnification, ×400). Positive cells are represented by red arrows. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (n=5/group). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 vs. the negative control; #P<0.05 vs. 160 µg/kg melittin; △P<0.05 vs. 320 µg/kg melittin. CD, cluster of differentiation; SDF-1α, stromal cell-derived factor-1α; CXCR4, C-X-C chemo-kine receptor type 4; MVD, microvessel density (number of microvessels/field).

Fig. 8 indicates that SDF-1α expression decreased with melittin in a dose-dependent manner (control, 80.7±9.5; 160 µg/kg melittin, 65.2±4.0; 320 µg/kg melittin, 55.3±4.6; and 640 µg/kg melittin, 17.3±3.7; all P<0.05 vs. control).

CXCR4 expression levels decreased with melittin in a dose-dependent manner (control, 33.6±3.3; 160 µg/kg melittin, 27.9±3.6; 320 µg/kg melittin, 19.7±3.1; and 640 µg/kg melittin, 14.4±2.9; all P<0.05 vs. control; Fig. 8).

Discussion

EPCs are important in tumor angiogenesis, SDF-1α and its receptor, CXCR4, are key in stem cell homing, and melittin (a component of bee venom) exerts antitumor activity, although its underlying mechanisms remain unknown. Furthermore, osteosarcomas maintain a tumor microenvironment, which stimulates angiogenesis (12). Therefore, the aim of the present study was to examine the effects of melittin on EPCs and angiogenesis, and investigate the underlying mechanisms of these effects.

Melittin exposure decreased the viability of UMR-106 cells and EPCs, with IC50 values of 6.33 and 4.51 µg/ml, respectively. Furthermore, melittin decreased EPC adhesion, migration and tube formation when compared with the control and SDF-1α-treated cells. Compared with the control. In addition, the expression levels of p-AKT, p-ERK1/2, SDF-1α and CXCR4 in UMR-106 cells and EPCs were decreased by melittin administration. The proportions of CD34/CD133 double-positive cells were 16.4±10.4% in the control cells, and 7.0±4.4, 2.9±1.2 and 1.3±0.3% in tumors treated with 160, 320 and 640 µg/kg melittin per day, respectively (all P<0.05). At 11 days, melittin reduced the tumor size compared with the control (control, 4.8±1.3 cm3; melittin, 3.2±0.6, 2.6±0.5, and 2.0±0.2 cm3 for 160, 320 and 640 µg/kg, respectively; all P<0.05). Furthermore, melittin decreased MVD, and SDF-1α and CXCR4 protein expression levels in tumor tissue samples.

EPCs migrate to tumor tissues and are involved in tumor angiogenesis; thus they present as a potential target in treatment strategies against tumor angiogenesis. Numerous stages of the process could be targeted, such as EPC mobilization, recruitment and/or differentiation. As osteosarcomas are tumors that actively promote angiogenesis (12), EPC targeting may provide a novel approach for osteosarcoma therapy (36).

EPCs are pluripotent stem cells, which have the potential to differentiate into mature endothelial cells (37). However, the exact role of the SDF-1α/CXCR4 signaling pathway in EPC-mediated angiogenesis in osteosarcomas remains unclear. In the present study, melittin significantly inhibited the angiogenesis ability of EPCs, which is induced by SDF-1α. The present study demonstrates that this inhibition is mediated by the melittin-induced inhibition of AKT and ERK1/2 phosphorylation. Therefore, the results suggest that melittin inhibits angiogenesis in EPCs via inhibiting the SDF-1α/CXCR4 signaling pathway. Results from the in vivo experiment further suggest that melittin may be administered to control the growth of osteosarcomas. The local injection approach decreased the likelihood of inducing a systemic reaction. In addition, previous studies have indicated that melittin exerts certain beneficial effects against cancer, such as decreased tumor invasion and decreased expression of proteins involved in tumor progression and invasion (38,39).

As with white blood cell homing to inflammatory tissues, EPC homing to tumors is dependent on SDF-1α and its receptor, CXCR4. The activation of the SDF-1α/CXCR4 signaling pathway is important in EPC migration and angiogenesis in tumors (19). The activation of CXCR4 by SDF-1α stimulates various downstream signaling pathways, such as phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT and mitogen-activated protein kinase/ERK1/2 (40–43). EPC homing and migration are improved by the upregulation of CXCR4 (44), as well as by the improvement of signaling pathways that are mediated by CXCR4 (45). Furthermore, tumor and stromal cells are the predominant source of SDF-1α in the tumor microenvironment (46).

CXCR4 is expressed on EPCs (47,48) and directs the cells toward tumors to induce angiogenesis (49). In addition, CXCR4 has been involved in osteosarcoma growth and metastases (50,51). The present study indicated that melittin may decrease the levels of p-AKT and ERK1/2 via reduced expression of CXCR4 on EPCs. A previous study demonstrated that melittin inhibits the PI3K/AKT/mechanistic target of rapamycin signaling pathway in breast cancer cells (52). However, further studies are required to elucidate the precise mechanisms involved.

In the present study, in vivo experiments demonstrated that melittin may reduce the number of CD34/CD133 double-positive cells in a mouse tibial tumor in situ. CD34/CD133 double-positive cells are considered to be EPCs (53). The melittin-treated tumors were also observed to have a lower MVD when compared with that of the controls. MVD is assessed using CD105, which is a vascular endothelial cell proliferation marker (54). CD105 is more effective than other endothelial cell markers (such as CD31 CD34, factor VIII-related antigen) as it is expressed only in the vascular endothelial cells of tumor tissues and not in the vessels of healthy tissues (55). This characteristic allows only the angiogenesis process in tumors to be assessed. The present study demonstrated that melittin may effectively reduce osteosarcoma-induced angiogenesis.

There were certain limitations of the present study. It was performed in animals and further studies in animals are required prior to eventual clinical trials. In addition, the present study was not designed to determine the exact mechanisms underlying EPC-modulated angiogenesis in osteosarcoma. However, the current study may aid in the design of novel studies to address this issue.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that the SDF-1α/CXCR4 signaling pathway is important in EPC-modulated tumor angiogenesis. Melittin decreased EPC viability, migration and tube formation, and decreased the expression levels of p-AKT and ERK1/2. Further studies are required to assess the effects of melittin on angiogenesis modulated by EPCs in osteosarcoma.

Acknowledgments

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 30873275).

References

- 1.Picci P. Osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma) Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eilber F, Giuliano A, Eckardt J, Patterson K, Moseley S, Goodnight J. Adjuvant chemotherapy for osteosarcoma: A randomized prospective trial. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:21–26. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernthal NM, Federman N, Eilber FR, Nelson SD, Eckardt JJ, Eilber FC, Tap WD. Long-term results (>25 years) of a randomized, prospective clinical trial evaluating chemotherapy in patients with high-grade, operable osteosarcoma. Cancer. 2012;118:5888–5893. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whelan JS, Jinks RC, McTiernan A, Sydes MR, Hook JM, Trani L, Uscinska B, Bramwell V, Lewis IJ, Nooji MA, et al. Survival from high-grade localised extremity osteosarcoma: Combined results and prognostic factors from three European Osteosarcoma Intergroup randomised controlled trials. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:1607–1616. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pluda JM. Tumor-associated angiogenesis: Mechanisms, clinical implications, and therapeutic strategies. Semin Oncol. 1997;24:203–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Bont ES, Guikema JE, Scherpen F, Meeuwsen T, Kamps WA, Vellenga E, Bos NA. Mobilized human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells enhance tumor growth in a nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient mouse model of human non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7654–7659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan HX, Cheng LM, Wang J, Hu LS, Lu GX. Angiogenic potential difference between two types of endothelial progenitor cells from human umbilical cord blood. Cell Biol Int. 2006;30:1018–1027. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, Kalka C, Pastore C, Silver M, Kearne M, Magner M, Isner JM. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res. 1999;85:221–228. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.85.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kryczek I, Wei S, Keller E, Liu R, Zou W. Stroma-derived factor (SDF-1/CXCL12) and human tumor pathogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;292:C987–C995. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00406.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vajkoczy P, Blum S, Lamparter M, Mailhammer R, Erber R, Engelhardt B, Vestweber D, Hatzopoulos AK. Multistep nature of microvascular recruitment of ex vivo-expanded embryonic endothelial progenitor cells during tumor angiogenesis. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1755–1765. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mukai N, Akahori T, Komaki M, Li Q, Kanayasu-Toyoda T, Ishii-Watabe A, Kobayashi A, Yamaguchi T, Abe M, Amagasa T, Morita I. A comparison of the tube forming potentials of early and late endothelial progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:430–440. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Uehara F, Tome Y, Miwa S, Hiroshima Y, Yano S, Yamamoto M, Mii S, Maehara H, Bouvet M, Kanaya F, Hoffman RM. Osteosarcoma cells enhance angiogenesis visualized by color-coded imaging in the in vivo Gelfoam® assay. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:1490–1494. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mueller SM, Mizuno S, Gerstenfeld LC, Glowacki J. Medium perfusion enhances osteogenesis by murine osteosarcoma cells in three-dimensional collagen sponges. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:2118–2126. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.12.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumarasuriyar A, Murali S, Nurcombe V, Cool SM. Glycosaminoglycan composition changes with MG-63 osteosarcoma osteogenesis in vitro and induces human mesenchymal stem cell aggregation. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:501–511. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonig H, Priestley GV, Oehler V, Papayannopoulou T. Hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPC) from mobilized peripheral blood display enhanced migration and marrow homing compared to steady-state bone marrow HPC. Exp Hematol. 2007;35:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Müller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, McClanahan T, Murphy E, Yuan W, Wagner SN, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim J, Mori T, Chen SL, Amersi FF, Martinez SR, Kuo C, Turner RR, Ye X, Bilchik AJ, Morton DL, Hoon DS. Chemokine receptor CXCR4 expression in patients with melanoma and colorectal cancer liver metastases and the association with disease outcome. Ann Surg. 2006;244:113–120. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217690.65909.9c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun YX, Schneider A, Jung Y, Wang J, Dai J, Wang J, Cook K, Osman NI, Koh-Paige AJ, Shim H, et al. Skeletal localization and neutralization of the SDF-1(CXCL12)/CXCR4 axis blocks prostate cancer metastasis and growth in osseous sites in vivo. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:318–329. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petit I, Jin D, Rafii S. The SDF-1-CXCR4 signaling pathway: A molecular hub modulating neo-angiogenesis. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oren Z, Shai Y. Selective lysis of bacteria but not mammalian cells by diastereomers of melittin: Structure-function study. Biochemistry. 1997;36:1826–1835. doi: 10.1021/bi962507l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kubo H, Loegering DA, Adolphson CR, Gleich GJ. Cytotoxic properties of eosinophil granule major basic protein for tumor cells. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1999;118:426–428. doi: 10.1159/000024154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazarev VN, Parfenova TM, Gularyan SK, Misyurina OY, Akopian TA, Govorun VM. Induced expression of melittin, an antimicrobial peptide, inhibits infection by Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma hominis in a HeLa cell line. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19:133–137. doi: 10.1016/S0924-8579(01)00479-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li B, Gu W, Zhang C, Huang XQ, Han KQ, Ling CQ. Growth arrest and apoptosis of the human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line BEL-7402 induced by melittin. Onkologie. 2006;29:367–371. doi: 10.1159/000094711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yeo SW, Seo JC, Choi YH. Induction of the growth inhibition and apoptosis by bee venom in human breast carcinoma MCF-7 cells. J Kor Acup Mox Soc. 2003;20:45–62. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jang MH, Shin MC, Lim S, Han SM, Park HJ, Shin I, Lee JS, Kim KA, Kim EH, Kim CJ. Bee venom induces apoptosis and inhibits expression of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA in human lung cancer cell line NCI-H1299. J Pharmacol Sci. 2003;91:95–104. doi: 10.1254/jphs.91.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huh JE, Baek YH, Lee MH, Choi DY, Park DS, Lee JD. Bee venom inhibits tumor angiogenesis and metastasis by inhibiting tyrosine phosphorylation of VEGFR-2 in LLC-tumor-bearing mice. Cancer Lett. 2010;292:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho HJ, Jeong YJ, Park KK, Park YY, Chung IK, Lee KG, Yeo JH, Han SM, Bae YS, Chang YC. Bee venom suppresses PMA-mediated MMP-9 gene activation via JNK/p38 and NF-kappaB-dependent mechanisms. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;127:662–668. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu S, Yu M, He Y, Xiao L, Wang F, Song C, Sun S, Ling C, Xu Z. Melittin prevents liver cancer cell metastasis through inhibition of the Rac1-dependent pathway. Hepatology. 2008;47:1964–1973. doi: 10.1002/hep.22240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo W, Feng JM, Yao L, Sun L, Zhu GQ. Transplantation of endothelial progenitor cells in treating rats with IgA nephropathy. BMC Nephrol. 2014;15:110. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-15-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Quaranta P, Antonini S, Spiga S, Mazzanti B, Curcio M, Mulas G, Diana M, Marzola P, Mosca F, Longoni B. Co-transplantation of endothelial progenitor cells and pancreatic islets to induce long-lasting normoglycemia in streptozotocin-treated diabetic rats. PLoS One. 2014;9:e94783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Massa M, Rosti V, Ramajoli I, Campanelli R, Pecci A, Viarengo G, Meli V, Marchetti M, Hoffman R, Barosi G. Circulating CD34+, CD133+, and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2-positive endothelial progenitor cells in myelofibrosis with myeloid metaplasia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5688–5695. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fritzenwanger M, Lorenz F, Jung C, Fabris M, Thude H, Barz D, Figulla HR. Differential number of CD34+, CD133+ and CD34+/CD133+ cells in peripheral blood of patients with congestive heart failure. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14:113–117. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-14-3-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fisher JL, Mackie PS, Howard ML, Zhou H, Choong PF. The expression of the urokinase plasminogen activator system in metastatic murine osteosarcoma: An in vivo mouse model. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:1654–1660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai KX, Tse LY, Leung C, Tam PK, Xu R, Sham MH. Suppression of lung tumor growth and metastasis in mice by adeno-associated virus-mediated expression of vasostatin. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:939–949. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weidner N, Semple JP, Welch WR, Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis and metastasis--correlation in invasive breast carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199101033240101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ta HT, Dass CR, Choong PF, Dunstan DE. Osteosarcoma treatment: State of the art. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:247–263. doi: 10.1007/s10555-009-9186-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu S, Wen H, Jiang H. Urotensin II promotes the proliferation of endothelial progenitor cells through p38 and p44/42 MAPK activation. Mol Med Rep. 2012;6:197–200. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2012.899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Park JH, Jeong YJ, Park KK, Cho HJ, Chung IK, Min KS, Kim M, Lee KG, Yeo JH, Park KK, Chan YC. Melittin suppresses PMA-induced tumor cell invasion by inhibiting NF-kappaB and AP-1-dependent MMP-9 expression. Mol Cells. 2010;29:209–215. doi: 10.1007/s10059-010-0028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fan Q, Hu Y, Pang H, Sun J, Wang Z, Li J. Melittin protein inhibits the proliferation of MG63 cells by activating inositol-requiring protein-1α and X-box binding protein 1-mediated apoptosis. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:1365–1370. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2014.1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gao H, Priebe W, Glod J, Banerjee D. Activation of signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 and focal adhesion kinase by stromal cell-derived factor 1 is required for migration of human mesenchymal stem cells in response to tumor cell-conditioned medium. Stem Cells. 2009;27:857–865. doi: 10.1002/stem.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Huang CY, Lee CY, Chen MY, Yang WH, Chen YH, Chang CH, Hsu HC, Fong YC, Tang CH. Stromal cell-derived factor-1/CXCR4 enhanced motility of human osteosarcoma cells involves MEK1/2, ERK and NF-kappaB-dependent pathways. J Cell Physiol. 2009;221:204–212. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petit I, Goichberg P, Spiegel A, Peled A, Brodie C, Seger R, Nagler A, Alon R, Lapidot T. Atypical PKC-zeta regulates SDF-1-mediated migration and development of human CD34+ progenitor cells. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:168–176. doi: 10.1172/JCI200521773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu DY, Tang CH, Yeh WL, Wong KL, Lin CP, Chen YH, Lai CH, Chen YF, Leung YM, Fu WM. SDF-1alpha up-regulates interleukin-6 through CXCR4, PI3K/Akt, ERK, and NF-kappaB-dependent pathway in microglia. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;613:146–154. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smadja DM, Bièche I, Uzan G, Bompais H, Muller L, Boisson-Vidal C, Vidaud M, Aiach M, Gaussem P. PAR-1 activation on human late endothelial progenitor cells enhances angiogenesis in vitro with upregulation of the SDF-1/CXCR4 system. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:2321–2327. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000184762.63888.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walter DH, Haendeler J, Reinhold J, Rochwalsky U, Seeger F, Honold J, Hoffman J, Urbich C, Lehmann R, Arenza-Seisdesdos F, et al. Impaired CXCR4 signaling contributes to the reduced neovascularization capacity of endothelial progenitor cells from patients with coronary artery disease. Circ Res. 2005;97:1142–1151. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000193596.94936.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maksym RB, Tarnowski M, Grymula K, Tarnowksa J, Wysoczynski M, Liu R, Czerny B, Ratajczak J, Kucia M, Ratajczak MZ. The role of stromal-derived factor-1--CXCR7 axis in development and cancer. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;625:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.04.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamaguchi J, Kusano KF, Masuo O, Kawamoto A, Silver M, Murasawa S, Bosch-Marce M, Masuda H, Losordo DW, Isner JM, Asahara T. Stromal cell-derived factor-1 effects on ex vivo expanded endothelial progenitor cell recruitment for ischemic neovascularization. Circulation. 2003;107:1322–1328. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000055313.77510.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Loetscher M, Geiser T, O'Reilly T, Zwahlen R, Baggiolini M, Moser B. Cloning of a human seven-transmembrane domain receptor, LESTR, that is highly expressed in leukocytes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:232–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis. In: Holland JF, Bast RC, Morton DL, editors. Cancer Medicine. 4th edition. Williams & Wilkins; Baltimore: 1997. pp. 181–204. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lin F, Zheng SE, Shen Z, Tang LN, Chen P, Sun YJ, Zhao H, Yao Y. Relationships between levels of CXCR4 and VEGF and blood-borne metastasis and survival in patients with osteosarcoma. Med Oncol. 2011;28:649–653. doi: 10.1007/s12032-010-9493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang P, Dong L, Yan K, Long H, Yang TT, Dong MQ, Zhou Y, Fan QY, Ma BA. CXCR4-mediated osteosarcoma growth and pulmonary metastasis is promoted by mesenchymal stem cells through VEGF. Oncol Rep. 2013;30:1753–1761. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jeong YJ, Choi Y, Shin JM, Cho HJ, Kang JH, Park KK, Choe JY, Bae YS, Han SM, Kim CH, Chang HW, Chang YC. Melittin suppresses EGF-induced cell motility and invasion by inhibiting PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in breast cancer cells. Food Chem Toxicol. 2014;68:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2014.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu G, Song M, Wang H, Zhao G, Yu Z, Yin Y, Zhao X, Huang L. Young environment reverses the declined activity of aged rat-derived endothelial progenitor cells: involvement of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. Ann Vasc Surg. 2009;23:519–534. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brewer CA, Setterdahl JJ, Li MJ, Johnston JM, Mann JL, McAsey ME. Endoglin expression as a measure of microvessel density in cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:224–228. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)00864-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wikström P, Lissbrant IF, Stattin P, Egevad L, Bergh A. Endoglin (CD105) is expressed on immature blood vessels and is a marker for survival in prostate cancer. Prostate. 2002;51:268–275. doi: 10.1002/pros.10083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]