Abstract

Smith–Magenis syndrome (SMS) and Potocki–Lupski syndrome (PTLS) are reciprocal contiguous gene syndromes within the well-characterized 17p11.2 region. Approximately 3.6 Mb microduplication of 17p11.2, known as PTLS, represents the mechanistically predicted homologous recombination reciprocal of the SMS microdeletion, both resulting in multiple congenital anomalies. Mouse model studies have revealed that the retinoic acid–inducible 1 gene (RAI1) within the SMS and PTLS critical genomic interval is the dosage-sensitive gene responsible for the major phenotypic features in these disorders. Even though PTLS and SMS share the same genomic region, clinical manifestations and behavioral issues are distinct and in fact some mirror traits may be on opposite ends of a given phenotypic spectrum. We describe the neurobehavioral phenotypes of SMS and PTLS patients during different life phases as well as clinical guidelines for diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach once diagnosis is confirmed by array comparative genomic hybridization or RAI1 gene sequencing. The main goal is to increase awareness of these rare disorders because an earlier diagnosis will lead to more timely developmental intervention and medical management which will improve clinical outcome.

Keywords: congenital heart disease, autism, intellectual disability, mirror traits, gene dosage

Introduction

The proximal short arm of chromosome 17 is a genomic region that is prone to rearrangements which have been extensively characterized elsewhere.1 2 Several distinct genomic disorders map to this region including the autosomal dominant peripheral neuropathies such as Charcot–Marie–Tooth disease type 1A (CMT1A, MIM#118220) and hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP, MIM#162500), the chromosomal microduplication/microdeletion syndromes, Potocki–Lupski syndrome (PTLS, MIM#610883), and Smith–Magenis syndrome (SMS, MIM#182290), as well as the newly described PMP22-RAI1 duplication syndrome (Yuan et al, unpublished data, 2015).

Although haploinsufficiency of the single retinoic acid–induced gene (RAI1) is responsible for much of the phenotype in SMS,3 4 both SMS and PTLS are examples of contiguous gene syndromes (CGS), as the clinical features of each are due to abnormal dosage and variation of physically contiguous yet functionally unrelated genes in the 17p11.2 genomic region.5 The mechanism leading to genomic rearrangements in common microdeletion syndromes was first elucidated in SMS.6 Interestingly, the clinical syndrome associated with duplication 17p11.2 (now known as PTLS) was initially defined based on the shared molecular structure among patients, the duplication representing the mechanistically predicted homologous recombination reciprocal of the SMS microdeletion.7 The prevalence for SMS and PTLS is approximately 1 in 25,000.2 8

SMS and PTLS were the first reported reciprocal CGS, associated with a common approximately 3.6 Mb deletion and duplication, respectively, due to many low copy repeats in the region; however, uncommon deletions and duplication also occur.6 7 9 Even though PTLS and SMS share the same genomic region, clinical manifestations and behavioral issues are distinct and in fact some traits may be on opposite ends of a given phenotypic spectrum. Other genomic regions which are prone to reciprocal rearrangements include 1q21.2, 7q11.23 (Williams-Beuren region), and 16p11.2. In all of these reciprocal syndromes, some clinical features may appear as opposing traits in the deletion versus the duplication patient (or mouse model). The term mirror traits is used to describe this intriguing phenomenon.10 Evaluating SMS and PTLS patients, and studying mouse models, has helped elucidate the function of the genes within the region and their role in the phenotype of these disorders.

Before the broad utilization of array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) in the clinical laboratory, the diagnosis of SMS and PTLS relied upon clinical suspicion and high-resolution G-banded chromosome analysis in conjunction with specific fluorescent in situ hybridization studies. In the past, many patients were undiagnosed due to the poor resolution of G-banded chromosome analysis to detect microdeletion and microduplication in this region. Currently, routine aCGH (also known as chromosomal microarray) will detect all common and uncommon SMS deletions and PTLS duplications. Sequence analysis of RAI1 is necessary to detect point mutations as seen in the minority of persons with SMS.

Smith–Magenis Syndrome

SMS was first described in two male infants with congenital cardiovascular disease and palatal clefts who both harbored a visible cytogenetic deletion of 17p11.2.11 Since that time more than 100 patients have been described in the medical literature and the phenotypic, cognitive, and neurobehavioral features have been well characterized. SMS is a multiple congenital anomalies disorder and is often recognized in infancy or early childhood because of dysmorphic craniofacial features (Fig. 1), hypotonia, and developmental delay. Congenital cardiovascular disease (e.g., septal defects, tetralogy of Fallot), which is present in approximately 35% of patients,12 13 14 often prompts early testing with aCGH. Renal and central nervous system (CNS) anomalies are less frequently observed. Other common comorbid features include refractive errors (typically myopia), frequent otitis media, hearing impairment (conductive, sensorineural, or mixed), short stature, scoliosis, obesity (in late childhood and adulthood), and seizures.15 16 17 18 If the diagnosis is not apparent by these physical and systemic features, it will be obvious by the striking neurobehavioral characteristics, specifically severe sleep and behavioral disturbances, which begin to manifest by the second or third year of life. Once the diagnosis of SMS is established by aCGH, a multidisciplinary approach to medical, developmental, and behavioral therapy is recommended.

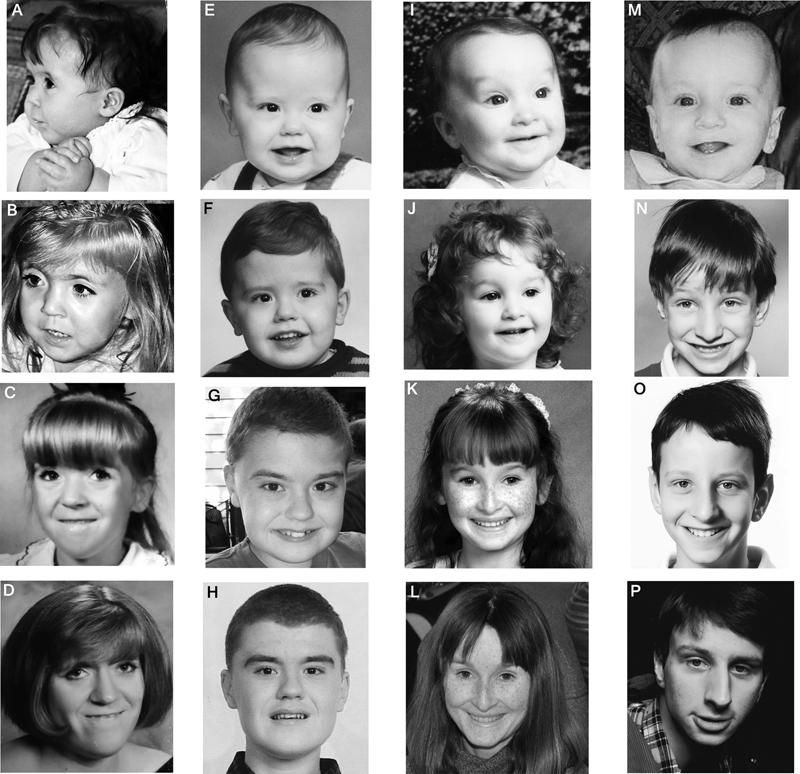

Fig. 1.

Facial features of Smith–Magenis syndrome (SMS) (A–H) and Potocki–Lupski syndrome (PTLS) (I–P). Common facial features of SMS include frontal prominence, synophrys, malar hypoplasia, and prognathia (more pronounced with age). Female with SMS (Patient number BAB 468), ages 7 months (A), 2 years (B), 9 years (C), 21 years (D). Male with SMS, ages 23 months (E), 3 years (F), 12 years (G), 17 years (H). Facial features more common in PTLS include inverted triangle shape, down slanting palpebral fissures, and relatively small jaw. Female with PTLS (Patient number BAB 1006), ages 8 months (I), 3 years (J), 10 years (K), 28 years (L). Male with PTLS (Patient number BAB 1690), ages 6 months (M), 6 years (N), 10 years (O), 19 years (P).

Cognitive, Developmental, and Behavioral Aspects of SMS

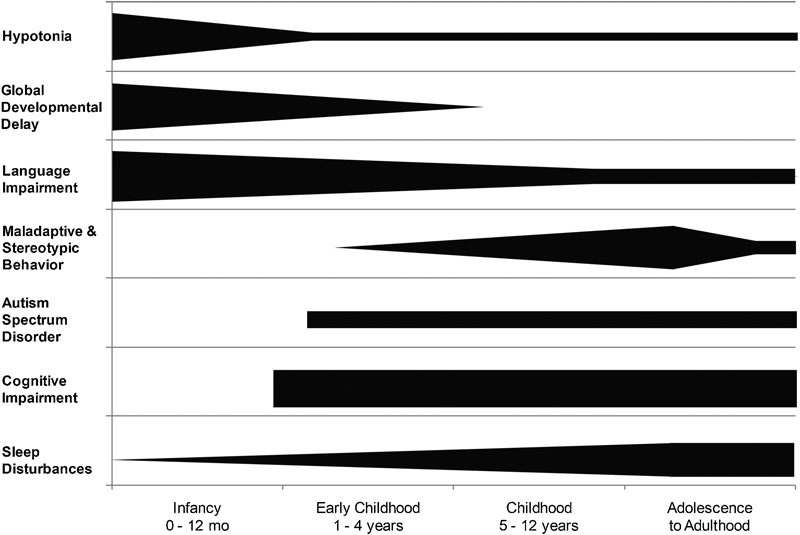

The common neurobehavioral features of SMS are shown in Fig. 2. In the absence of major organ system anomalies, a diagnosis of SMS is rarely if ever suspected in infancy as the dysmorphic features can be subtle and nonspecific. In addition, while hypotonia and hyporeflexia are often present in early infancy, the degree is typically mild; thus, an underlying genetic disorder is not always considered.19 20 However, global developmental delay is usually apparent by late infancy, prompting referral to early childhood intervention. Developmental delays will persist through early childhood, and cognitive impairment and poor adaptive function are apparent by the early elementary school years.21 During this period, the child with SMS will begin to display increasingly negative behaviors such as prolonged tantrums, self-injury, aggression, and disrupted sleep.19 22 Indeed, in those children without major congenital anomalies, the diagnosis of SMS is often suspected by virtue of their severe behavioral and sleep disturbances.23

Fig. 2.

Neurodevelopmental aspects of Smith–Magenis syndrome. A schematic representation of the trends of key neurodevelopmental features of SMS across age groups. Cognitive impairment, maladaptive and stereotypic behaviors, and sleep disturbances are observed in all patients with SMS; however, autism spectrum disorder can be variable.

Self-injurious behaviors are present in more than 90% of patients and have been demonstrated to correlate with age and level of intellectual functioning.24 25 These harming behaviors are typically not present before 18 months of age, and usually start with frequent head banging. Other self-injurious behaviors reported include self-biting, slapping, and skin picking (e.g., surgical wounds, insect bite sites, cuticles, and areas of minor abrasions). Daily living skills become challenging for families as patients age, as they will present with very frequent outbursts/prolonged tantrums, attention seeking, hyperactivity, impulsivity, disobedience, and aggression.24 26 Two self-injurious behaviors—onychotillomania (nail picking/pulling) and polyembolokoilamania (insertion of foreign body objects into body orifices)—develop along with mood instability and anxiety, usually after puberty, and will exacerbate during adolescence.8 These features, when present, are distinctive for SMS.8 26 In contrast to the maladaptive behaviors, persons with SMS often display a stereotypical hand clasp and self-hug as an expression of delight, excitement, and/or happiness.27

The developmental and cognitive profiles of SMS are well documented.19 20 21 The majority of individuals with SMS test within the moderate range of intellectual disability21 26; however, the substantial negative behaviors in these patients lead to impaired adaptive function and a lower perceived cognition for many individuals (L Potocki, MD, personal oral communication, 2015). Adaptive function is most impaired in communication and socialization.21 Regression or loss of skills is not a feature of this condition19 25; however, complications due to epilepsy or unrecognized severe to profound hearing impairment may lead to a more severe neurocognitive phenotype. Autistic features and/or autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has been reported in as many as 90% of individuals with SMS, implementing the Social Responsiveness Scale, and the severity ranges from mild to severe autism.26 Importantly, the diagnosis of SMS may be missed in an individual with severe autism who lacks other organ system anomalies.

Sleep Disturbances and Neurologic Findings

Sleep disturbances are reported in nearly all persons with SMS and together with the maladaptive behavior is the most pervasive feature of the disorder. These problems are a common chief complaint among parents because they cause substantial distress within families. Sleep disorders in SMS are associated with an inversion of the circadian rhythm of melatonin which is observed in persons with the deletion and in persons with point mutations in RAI1.22 28 29

Infants with SMS are described as angelic and quiet babies with increased sleepiness and daytime napping.19 Toddlers and older children will usually manifest with increased nocturnal awakening, and excessive daytime sleepiness. Polysomnography (sleep studies) will reveal decreased REM sleep, fragmented and shortened sleep cycles, and abnormal (decreased) daytime sleep latency.22 Adolescents and adults will continue to have sleep disturbances; however, initiation of sleep seems to be more disturbed in this age group.23 Approaching sleep problems is important, as maladaptive and negative behaviors are correlated with disrupted sleep. Treatment for the sleep disturbances in SMS is suboptimal at best. Oral melatonin, given just before bedtime, is effective in a proportion of patients. Beta blockers—used to suppress endogenous melatonin secretion—during daylight hours, paired with oral melatonin supplementation at bedtime, has also had some success.30 31 32 Unfortunately, there are no controlled clinical trials demonstrating efficacy of these medications and supplements in SMS. Clinical trials investigating bright light treatment are ongoing.33

Various types of CNS abnormalities have been reported in SMS, yet none are considered to be specific or characteristic for this condition.12 14 19 23 As CNS anomalies revealed by CT scan performed in a systematic multidisciplinary study were present in only 52% of patients,12 cranial imaging has not historically been recommended unless indicated by clinical features such as overt seizure(s). However, more recent case reports suggest that CNS abnormalities including migrational and other structural anomalies may be more prevalent in SMS.34 35 Clinical seizures are seen in up to 20 to 30% of patients but an abnormal electroencephalogram (EEG) is recorded in as many as approximately 50% of the patients undergoing sleep study.16 19 22 Catamenial seizures (seizures exacerbated by menses) have also been reported.36

Recommendations and Management for SMS Patients

When the diagnosis of SMS is suspected based on clinical findings or if a patient presents with hypotonia, developmental delay, or congenital anomalies, the first-line testing is aCGH. If aCGH is normal, yet the diagnosis of SMS is still suspected, sequence analysis of RAI1 gene should be performed. The deletion in SMS typically occurs as a de novo event and as such the recurrence risk would be low for future pregnancies of parents with a previously affected child. There are few reports of mosaic transmission where a parent harbored a low-level mosaic SMS deletion, yet the child was nonmosaic and expressed the common SMS phenotype.37 38 39 To our knowledge, no constitutional SMS transmission has been reported; however, due to possibility of somatic mosaicism and/or chromosomal rearrangements, parental studies are recommended.39 Patients should be referred to medical genetics, regardless of the chromosomal basis of SMS, for further counseling and recurrence risk discussion.

Behavioral and educational intervention is extremely challenging in this population. General behavior modification strategies should be employed early, as individuals with SMS respond best to orderly direction, clear boundaries, and predictable schedules. As for any developmental disorder, cognitively appropriate communication is a key to successful intervention. In addition, the school-aged child with SMS will benefit by having a 1:1 aide in the classroom to redirect negative behaviors, and focus attention to the tasks at hand. A developmental pediatrician and/or developmental psychologists are invaluable members of the health and education care team in SMS. Consultation should be provided within the first few years of life and follow-up should ensue at least yearly, as the child and young adult with SMS will face a myriad of challenges both in and out of school. Besides behavioral management, early childhood intervention and various therapies (speech, physical, and occupational), multidisciplinary evaluations are necessary due to comorbidities associated with this disorder. The following guidelines are based on a review of the medical literature:

Developmental assessment and follow up (see above).

Neurologic evaluation at diagnosis: EEG can be considered in those without overt seizures because it can be helpful in ruling out subclinical seizures which will impact treatment of behavioral issues.

Ophthalmologic examination on at least a yearly basis to evaluate for myopia, strabismus, and other anomalies.

Otolaryngologic evaluation to asses for palatal abnormalities and management of frequent otitis media.

Audiology evaluation, to monitor for hearing loss. If testing is normal, hearing should be rechecked annually or as clinically indicated.

Echocardiographic screening should be performed at the time of diagnosis and referral to cardiologist if abnormalities are present.

Clinical evaluation for scoliosis, as this is a relatively common finding in SMS and develops with age and growth. Scoliosis survey can be performed upon clinical suspicion. Orthopedic referral if scoliosis is present.

Physical medicine and rehabilitation evaluation for hypotonia, low muscle mass, and scoliosis, if present.

Renal ultrasound to evaluate for possible renal/urologic anomalies. Referral to urology if abnormal or if suspicion of reflux.

Sleep medicine assessment with polysomnography at diagnosis and as clinically indicated to evaluate for obstructive sleep apnea and abnormal sleep patterns.

Laboratory studies including yearly fasting lipid profile for risk of hypercholesterolemia, thyroid function studies, and routine urinalysis.

Families should be assessed for psychosocial support and referred for interventions that will assure an optimal environment for the patient and the entire family.

Potocki–Lupski Syndrome

Rare case reports of individuals with cytogenetically visible duplications of this region were published as early as the late 1970s.40 41 42 43 The molecular mechanism of the duplication—the recombination reciprocal of the SMS microdeletion—was reported in 2000, complete with a brief description of the proposed key clinical features of the condition based on seven patients.7 However, it was not until nearly a decade later when the clinical features of this microduplication syndrome were more thoroughly characterized.44 Since that time more than 50 individuals with PTLS have been reported in the medical literature.45 46 47

Like SMS, PTLS is a disorder associated with intellectual disability, behavioral disturbances, and organ system involvement. Given that SMS was recognized as a clinical syndrome nearly 20 years before PTLS, and that genomic duplications are generally better tolerated than deletions, it stands to reason that the clinical picture of PTLS would be much milder than that of SMS. While this is true for many patients, PTLS can manifest with severe hypotonia and failure to thrive (FTT) during infancy,48 severe congenital heart disease requiring early surgical intervention, or even cardiac transplantation49 50 51 and significant behavioral abnormalities.52 This stands in stark contrast to individuals with duplication 17p11.2 syndrome who escape diagnosis until the birth of a severely affected child.50 53

The main clinical aspects associated with PTLS include infantile hypotonia, poor feeding, FTT, congenital cardiovascular anomalies, and sleep-disordered breathing. Patients with PTLS have significantly lower weight for age, weight for length, and body mass index for age than the comparative reference population48 and they should be assessed for oropharyngeal dysfunction and treated with nutritional support. Cardiovascular anomalies have been reported in approximately 40% of these patients and aortic root dilatation (which can develop with age) and rhythm abnormalities can require pharmacologic intervention.54 Although sleep disturbance is often the chief complaint for the SMS patient, central and obstructive sleep apnea in PTLS is usually unrecognized until polysomnography is performed44 and occasionally is severe enough to require medical intervention (L Potocki, MD, personal oral communication, 2015). The vast majority of persons with PTLS have facial features which would not be considered as dysmorphic, though shared traits are observed (Fig. 1). Importantly, PTLS is a recently recognized syndrome, and there is still much to learn about the natural history of the disorder as well as the adult phenotype of these individuals.

Cognitive, Developmental, and Behavioral Aspects of PTLS

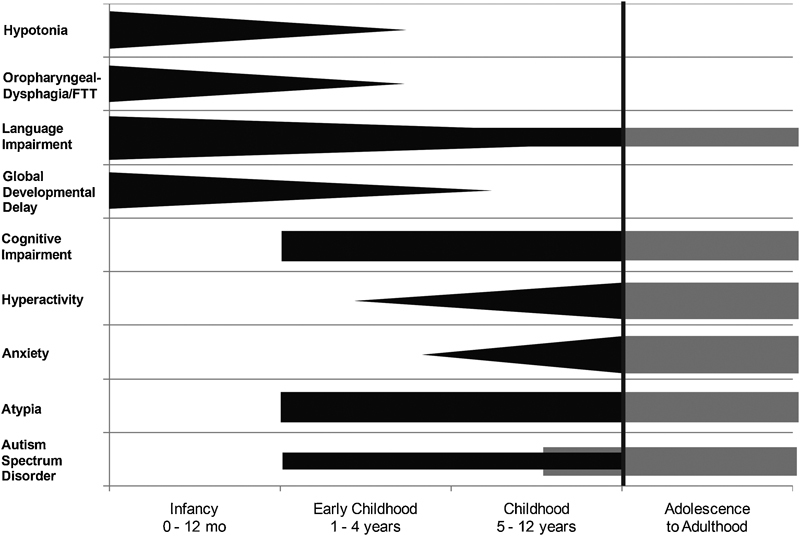

While the infant with PTLS comes to medical attention due to hypotonia and FTT, the older child is most often ascertained because of developmental delay, behavioral concerns, and cognitive impairment.44 Hypotonia contributes to poor oral motor and gross motor skills, and is a factor in poor feeding, poor articulation, and delayed walking to as late as 4 years. Speech delay is universally observed in PTLS, as are disorders of communication such as abnormalities in intonation and prosody.52 Approximately 50% of children studied displayed some signs of verbal apraxia, as difficulties with motor planning and/or sequencing sounds within words, and in a subset of children verbal language was not attained.44 52 Those patients with communicative speech will usually refer to themselves in third person and with a pedantic language and may talk with running commentaries and immediate or delayed echolalia. Receptive language is also impaired as are general measures of cognitive, executive, and adaptive functioning.52 PTLS patients may use augmentative communication as part of their expressive language by implementing manual signing or other systems such as picture exchange. When subjected to standardized analysis, the majority of individuals with PTLS fall within the moderate range of intellectual disability,52 though some will test in the borderline or nonimpaired range. Deficits of executive functioning include initiating activities, shifting activities, and employment of working memory.52

Behavioral difficulties of various types and severity are evident in PTLS. Atypicality has been reported in 100% of patients, though attention problems, withdrawal, somatization, and high levels of hyperactivity and anxiety have also been documented.52 Features within the autistic spectrum are also observed by parents and examiners. Of the ASD features, decreased eye contact, motor mannerisms or posturing, sensory hypersensitivity or preoccupation, repetitive behaviors, difficulty with transitions, lack of appropriate functional or symbolic play, and lack of joint attention are some of the most common. On a systematic evaluation using validated scoring systems (Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised [ADI-R] and Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-Generic [ADOS-G]), five of eight children met the criteria for ASD.52 Such autistic features have been observed in patients with the common duplication as well as in patients carrying smaller duplications involving the RAI1 gene,9 thus implicating this dosage-sensitive gene in the ASD phenotype in both PTLS and SMS.4 The most common neurobehavioral features of PTLS are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Neurodevelopmental aspects of Potocki–Lupski syndrome. A schematic representation of the trends of key neurodevelopmental features of PTLS across age groups. Cognitive impairment and atypia are observed in the majority of patients; however, more data are required (shaded area) to determine the prevalence of these features and of autism spectrum disorder in adolescents and adults with dup17p11.2.

Sleep Disturbances and Neurologic Findings

Sleep disturbances have not been a common compliant among parents of individuals with PTLS. Likewise, significant manifestation of airway obstruction has not been found on examination. However, of the 16 persons who had sleep studies in a multidisciplinary study, 14 of these were abnormal (with central and/or obstructive apnea being the most common finding) (L Potocki, MD, personal oral communication, 2015). EEG abnormalities have also been recorded; low occipital dominant rhythm (“alpha”) and generalized and/or focal epileptiform abnormalities (spikes, sharp waves, and spike and slow wave discharges) are some of the most common.44 Clinical or EEG seizures have not been reported as part of the phenotype of PTLS.

Recommendations and Management for PTLS

The vast majority of persons with PTLS are diagnosed by aCGH performed for hypotonia, FTT, developmental delay, and/or congenital heart disease (though all of these features may not be present in every patient). It is essential to understand that G-banded chromosome analysis will not detect this duplication (nor the SMS microdeletion) in most cases. Once a diagnosis is confirmed by aCGH, the patient should be referred to a clinical geneticist for counseling regarding the chromosomal basis of PTLS, recurrence risk, testing at-risk individuals, and medical management. Parental studies should be performed to assess for genomic rearrangement and/or duplication of this region. The risk for a person with PTLS to transmit this duplication is 50% with each pregnancy.50 53

Behavioral interventions are highly important in this population. Given that autistic spectrum disorder as well as atypia is seen in the majority of individuals with PTLS, a behavioral assessment should be performed at diagnosis and periodically thereafter. Specific intervention can be designed to maximize educational and social environments. Formal testing for autism spectrum should be strongly considered, implementing the ADI-R and the ADOS-G, as individuals with PTLS can meet criteria for ASD and derive benefit from specific therapeutic interventions. Speech and language therapy, implementing various strategies such as augmentative communication, should be instituted early. Patients with PTLS should follow up at least yearly with a developmental pediatrician or developmental psychologist who will be an essential member of the educational and health care teams. In addition to the behavioral management, early childhood intervention, and various therapies (feeding/oral-motor, speech, physical, and occupational), multidisciplinary evaluations are necessary due to comorbidities associated with this disorder. The following guidelines are based on review of the medical literature and clinical experience:

Developmental assessment and follow up.

Ophthalmologic examination on at least a yearly basis to evaluate for refractive error (typically hypermetropia) and strabismus.

Otolaryngologic evaluation to assess for anatomic causes of obstructive sleep apnea, when present.

Swallow function study in conjunction with a feeding evaluation to assess for oropharyngeal dysphagia, oral-motor function, and aspiration.

Hearing impairment is not a prominent feature of individuals with PTLS; however, assessment of hearing is warranted periodically if there is a significant speech and language delay. Repeat audiological studies as clinically indicated.

Echocardiographic screening with attention to the aortic root and great vessels and electrocardiographic exam at diagnosis. If abnormal, referral to cardiologist. If normal, follow up periodically (specific guidelines not yet established; recommended reevaluation after normal echocardiogram is every 2–3 years in childhood and adolescence, every 4–5 years in adulthood) for aortic root dilation.

Evaluate clinically for scoliosis as this is a relatively common finding in PTLS and develops with age and growth. Scoliosis survey can be performed upon clinical suspicion.

Physical medicine and rehabilitation evaluation if hypotonia, low muscle mass, and scoliosis are present.

Renal ultrasound to evaluate possible renal/urologic structural anomalies. Referral to urologist if abnormal.

Sleep study to assess for obstructive and/or central sleep apnea. Refer to sleep medicine if any abnormalities.

Families should be assessed for psychosocial support and if needed they should be assisted with interventions that will assure an optimal environment for the patient and the entire family.

Mouse Models

Animal models have contributed to the better understanding of SMS and PTLS. Human chromosome 17p11.2 is syntenic to the 32–34 cM region of murine chromosome 11.55 Pathogenesis of copy number variants as well as identification of dosage-sensitive genes has been elucidated through these models. The first mouse models were generated with the deletion (Dƒ(11)17/ + ) and duplication (Dp(11)17/ + ) of the critical region, respectively.56 Subsequently, RAI1 knock-in and knock-out mice were engineered and evaluated.57 Many of the clinical and behavioral aspects of these two syndromes—in particular many mirror traits such as those associated with body weight, metabolism, and activity level—have been recapitulated in these mouse models.56 58 59 60 61 These reports provide valuable insight into the pathophysiology of these conditions.

In general, the main clinical features that have been found in SMS mouse models are obesity and metabolic syndrome, craniofacial abnormalities, seizures, and abnormal EEG patterns. Male Dƒ(11)17/+ mice were hypoactive and had a shorter circadian period and reduced precision of the clock control, when compared with their wild-type littermates.60 62 Rai + /− mice have demonstrated that these features are a direct consequence of Rai1 gene haploinsufficiency.57

The phenotypic features of PTLS have also been recapitulated in the mouse model, in which low corporal weight, hyperactivity, increased anxiety behavior, and short-term memory deficiency are observed.62 Dp(11)17/+ mice also demonstrated abnormal social behavior in the sociability test which can be correlated with the patients' autistic behaviors.63 Duplication mice showed no significant difference with their wild-type littermates within the circadian cycle.62 Rai1 transgenics cause specific phenotypes of PTLS and several neurobehavioral traits.64 Double transgenic-Rai (I-Rai1) mice with overexpression of Rai1 in the forebrain showed PTLS-like phenotypes such as underweight, hyperactivity, and learning and memory deficits, suggesting the importance of Rai1 dosage in neurodevelopment or normal neuron function.65 These data also revealed that overexpression of Rai1 in forebrain is enough to cause hyperactivity, but it is not sufficient to elicit increased anxiety or abnormal social behaviors observed earlier in PTLS Dp(11)17/+ mice.65 Del and Dup mice were observed for the presence of self-injurious behavior, as it is a common behavior of SMS, but they showed no evidence of this type of behaviors.62

Discussion

We described the neurobehavioral phenotypes of SMS and PTLS and what to expect in persons with these genomic disorders during different life phases. The goal of this article is to increase awareness of these rare disorders among pediatricians so that patients are diagnosed early. An earlier diagnosis of these conditions will lead to more timely developmental intervention and medical management, which will improve clinical outcomes.

Although SMS and PTLS share the same genomic region, they are clinically distinct. Practitioners should be able to recognize the features of each, though the diagnosis is most often made by aCGH. In patients with normal aCGH and features of SMS, the RAI1 gene should be sequenced. Studies in human and mouse reveal that RAI1 within the SMS and PTLS critical genomic interval is a dosage-sensitive gene responsible for the major phenotypic features in these disorders. Nonetheless phenotypic variability may be at least partially explained by haploinsufficiency (SMS) or triplosensitivity (PTLS) of other genes within the common and uncommon intervals. Moreover, variant alleles on the non-rearranged chromosome may contribute to clinical variability.66

Once the diagnosis of SMS or PTLS is established, the patient should be referred to a clinical geneticist who will initiate and maintain multidisciplinary management of medical, developmental, and behavioral abnormalities. Discussions regarding recurrence risks for the parents and the patients are also important and can be addressed by the geneticist or a genetic counselor. Finally, the importance of family support cannot be overemphasized as persons with SMS and PTLS have challenging and maladaptive behaviors and neurodevelopmental abnormalities, which increase the level of stress for parents, siblings, and extended families.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. James R. Lupski and Dr. Katerina Walz for their critical reviews, Dr. Jorge Izquierdo for graphic designing, the many patients and families who participated in the clinical and molecular research studies of SMS and PTLS, and the families who contributed the photographs for this study.

References

- 1.Zody M C, Garber M, Adams D J. et al. DNA sequence of human chromosome 17 and analysis of rearrangement in the human lineage. Nature. 2006;440(7087):1045–1049. doi: 10.1038/nature04689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu P, Lacaria M, Zhang F, Withers M, Hastings P J, Lupski J R. Frequency of nonallelic homologous recombination is correlated with length of homology: evidence that ectopic synapsis precedes ectopic crossing-over. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;89(4):580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Slager R E, Newton T L, Vlangos C N, Finucane B, Elsea S H. Mutations in RAI1 associated with Smith-Magenis syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33(4):466–468. doi: 10.1038/ng1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fragoso Y D, Stoney P N, Shearer K D. et al. Expression in the human brain of retinoic acid induced 1, a protein associated with neurobehavioural disorders. Brain Struct Funct. 2015;220(2):1195–1203. doi: 10.1007/s00429-014-0712-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmickel R D. Contiguous gene syndromes: a component of recognizable syndromes. J Pediatr. 1986;109(2):231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(86)80377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen K S, Manian P, Koeuth T. et al. Homologous recombination of a flanking repeat gene cluster is a mechanism for a common contiguous gene deletion syndrome. Nat Genet. 1997;17(2):154–163. doi: 10.1038/ng1097-154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Potocki L, Chen K S, Park S S. et al. Molecular mechanism for duplication 17p11.2- the homologous recombination reciprocal of the Smith-Magenis microdeletion. Nat Genet. 2000;24(1):84–87. doi: 10.1038/71743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenberg F, Guzzetta V, Montes de Oca-Luna R. et al. Molecular analysis of the Smith-Magenis syndrome: a possible contiguous-gene syndrome associated with del(17)(p11.2) Am J Hum Genet. 1991;49(6):1207–1218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang F, Potocki L, Sampson J B. et al. Identification of uncommon recurrent Potocki-Lupski syndrome-associated duplications and the distribution of rearrangement types and mechanisms in PTLS. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86(3):462–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lupski J R. Structural variation mutagenesis of the human genome: impact on disease and evolution. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2015;56:419–436. doi: 10.1002/em.21943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith A CM McGavran L Waldstein G Deletion of the 17 short arm in two patients with facial clefts and congenital heart disease Am J Hum Genet 198234(Suppl):A410 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenberg F, Lewis R A, Potocki L. et al. Multi-disciplinary clinical study of Smith-Magenis syndrome (deletion 17p11.2) Am J Med Genet. 1996;62(3):247–254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960329)62:3<247::AID-AJMG9>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potocki L, Shaw C J, Stankiewicz P, Lupski J R. Variability in clinical phenotype despite common chromosomal deletion in Smith-Magenis syndrome [del(17)(p11.2p11.2)] Genet Med. 2003;5(6):430–434. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000095625.14160.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Edelman E A, Girirajan S, Finucane B. et al. Gender, genotype, and phenotype differences in Smith-Magenis syndrome: a meta-analysis of 105 cases. Clin Genet. 2007;71(6):540–550. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2007.00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen R M, Lupski J R, Greenberg F, Lewis R A. Ophthalmic manifestations of Smith-Magenis syndrome. Ophthalmology. 1996;103(7):1084–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(96)30563-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldman A M, Potocki L, Walz K. et al. Epilepsy and chromosomal rearrangements in Smith-Magenis Syndrome [del(17)(p11.2p11.2)] J Child Neurol. 2006;21(2):93–98. doi: 10.1177/08830738060210021201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elsea S H, Girirajan S. Smith-Magenis syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16(4):412–421. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5202009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lacaria M, Saha P, Potocki L. et al. A duplication CNV that conveys traits reciprocal to metabolic syndrome and protects against diet-induced obesity in mice and men. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(5):e1002713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gropman A L, Duncan W C, Smith A C. Neurologic and developmental features of the Smith-Magenis syndrome (del 17p11.2) Pediatr Neurol. 2006;34(5):337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolters P L, Gropman A L, Martin S C. et al. Neurodevelopment of children under 3 years of age with Smith-Magenis syndrome. Pediatr Neurol. 2009;41(4):250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Madduri N, Peters S U, Voigt R G, Llorente A M, Lupski J R, Potocki L. Cognitive and adaptive behavior profiles in Smith-Magenis syndrome. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(3):188–192. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200606000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Potocki L, Glaze D, Tan D X. et al. Circadian rhythm abnormalities of melatonin in Smith-Magenis syndrome. J Med Genet. 2000;37(6):428–433. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.6.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gropman A L, Elsea S, Duncan W C Jr, Smith A C. New developments in Smith-Magenis syndrome (del 17p11.2) Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20(2):125–134. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3280895dba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dykens E M, Smith A C. Distinctiveness and correlates of maladaptive behaviour in children and adolescents with Smith-Magenis syndrome. J Intellect Disabil Res. 1998;42(Pt 6):481–489. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.1998.4260481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Finucane B, Dirrigl K H, Simon E W. Characterization of self-injurious behaviors in children and adults with Smith-Magenis syndrome. Am J Ment Retard. 2001;106(1):52–58. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2001)106<0052:COSIBI>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laje G, Morse R, Richter W, Ball J, Pao M, Smith A C. Autism spectrum features in Smith-Magenis syndrome. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2010;154C(4):456–462. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finucane B M, Konar D, Haas-Givler B, Kurtz M B, Scott C I Jr. The spasmodic upper-body squeeze: a characteristic behavior in Smith-Magenis syndrome. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1994;36(1):78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.1994.tb11770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.De Leersnyder H, De Blois M C, Claustrat B. et al. Inversion of the circadian rhythm of melatonin in the Smith-Magenis syndrome. J Pediatr. 2001;139(1):111–116. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.115018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boone P M, Reiter R J, Glaze D G, Tan D X, Lupski J R, Potocki L. Abnormal circadian rhythm of melatonin in Smith-Magenis syndrome patients with RAI1 point mutations. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(8):2024–2027. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Leersnyder H, de Blois M C, Vekemans M. et al. beta(1)-adrenergic antagonists improve sleep and behavioural disturbances in a circadian disorder, Smith-Magenis syndrome. J Med Genet. 2001;38(9):586–590. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.9.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.De Leersnyder H. Inverted rhythm of melatonin secretion in Smith-Magenis syndrome: from symptoms to treatment. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17(7):291–298. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Poisson A, Nicolas A, Sanlaville D. et al. Smith-Magenis syndrome is an association of behavioral and sleep/wake circadian rhythm disorders [in French] Arch Pediatr. 2015;22(6):638–645. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2015.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.A Phase One Treatment Trial of the Circadian Sleep Disturbance in Smith-Magenis Syndrome (SMS) (NCT00506259) Clinical Trials.gov, 2007. Available at: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=smith+magenis&Search=Search. Accessed June 1, 2015

- 34.Capra V, Biancheri R, Morana G. et al. Periventricular nodular heterotopia in Smith-Magenis syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(12):3142–3147. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maya I, Vinkler C, Konen O. et al. Abnormal brain magnetic resonance imaging in two patients with Smith-Magenis syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(8):1940–1946. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith A C Gropman A Smith-Magenis syndrome In: Cassidy S Allanson J eds. Management of Genetic Syndromes, 3rd ed New York, NY: Wiley-Blackwell; 2010739–767. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zori R T, Lupski J R, Heju Z. et al. Clinical, cytogenetic, and molecular evidence for an infant with Smith-Magenis syndrome born from a mother having a mosaic 17p11.2p12 deletion. Am J Med Genet. 1993;47(4):504–511. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320470414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Juyal R C, Kuwano A, Kondo I, Zara F, Baldini A, Patel P I. Mosaicism for del(17)(p11.2p11.2) underlying the Smith-Magenis syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1996;66(2):193–196. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19961211)66:2<193::AID-AJMG13>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell I M, Yuan B, Robberecht C. et al. Parental somatic mosaicism is underrecognized and influences recurrence risk of genomic disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95(2):173–182. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feldman G M, Baumer J G, Sparkes R S. Brief clinical report: the dup(17p) syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1982;11(3):299–304. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320110306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magenis R E, Brown M G, Allen L, Reiss J. De novo partial duplication of 17p [dup(17)(p12----p11.2)]: clinical report. Am J Med Genet. 1986;24(3):415–420. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320240304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kozma C, Meck J M, Loomis K J, Galindo H C. De novo duplication of 17p [dup(17)(p12----p11.2)]: report of an additional case with confirmation of the cytogenetic, phenotypic, and developmental aspects. Am J Med Genet. 1991;41(4):446–450. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320410413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown A, Phelan M C, Patil S, Crawford E, Rogers R C, Schwartz C. Two patients with duplication of 17p11.2: the reciprocal of the Smith-Magenis syndrome deletion? Am J Med Genet. 1996;63(2):373–377. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19960517)63:2<373::AID-AJMG9>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Potocki L, Bi W, Treadwell-Deering D. et al. Characterization of Potocki-Lupski syndrome (dup(17)(p11.2p11.2)) and delineation of a dosage-sensitive critical interval that can convey an autism phenotype. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80(4):633–649. doi: 10.1086/512864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nakamine A, Ouchanov L, Jiménez P. et al. Duplication of 17(p11.2p11.2) in a male child with autism and severe language delay. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A(5):636–643. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gulhan Ercan-Sencicek A, Davis Wright N R, Frost S J. et al. Searching for Potocki-Lupski syndrome phenotype: a patient with language impairment and no autism. Brain Dev. 2012;34(8):700–703. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2011.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee C G, Park S J, Yim S Y, Sohn Y B. Clinical and cytogenetic features of a Potocki-Lupski syndrome with the shortest 0.25Mb microduplication in 17p11.2 including RAI1. Brain Dev. 2013;35(7):681–685. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2012.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soler-Alfonso C, Motil K J, Turk C L. et al. Potocki-Lupski syndrome: a microduplication syndrome associated with oropharyngeal dysphagia and failure to thrive. J Pediatr. 2011;158(4):655–65900. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sanchez-Valle A, Pierpont M E, Potocki L. The severe end of the spectrum: hypoplastic left heart in Potocki-Lupski syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(2):363–366. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yusupov R, Roberts A E, Lacro R V, Sandstrom M, Ligon A H. Potocki-Lupski syndrome: an inherited dup(17)(p11.2p11.2) with hypoplastic left heart. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A(2):367–371. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schmid M, Stary S, Blaicher W, Gollinger M, Husslein P, Streubel B. Prenatal genetic diagnosis using microarray analysis in fetuses with congenital heart defects. Prenat Diagn. 2012;32(4):376–382. doi: 10.1002/pd.2862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Treadwell-Deering D E, Powell M P, Potocki L. Cognitive and behavioral characterization of the Potocki-Lupski syndrome (duplication 17p11.2) J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(2):137–143. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181cda67e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Magoulas P L, Liu P, Gelowani V. et al. Inherited dup(17)(p11.2p11.2): expanding the phenotype of the Potocki-Lupski syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A(2):500–504. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jefferies J L, Pignatelli R H, Martinez H R. et al. Cardiovascular findings in duplication 17p11.2 syndrome. Genet Med. 2012;14(1):90–94. doi: 10.1038/gim.0b013e3182329723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carmona-Mora P, Molina J, Encina C A, Walz K. Mouse models of genomic syndromes as tools for understanding the basis of complex traits: an example with the Smith-Magenis and the Potocki-Lupski syndromes. Curr Genomics. 2009;10(4):259–268. doi: 10.2174/138920209788488508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walz K, Caratini-Rivera S, Bi W. et al. Modeling del(17)(p11.2p11.2) and dup(17)(p11.2p11.2) contiguous gene syndromes by chromosome engineering in mice: phenotypic consequences of gene dosage imbalance. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(10):3646–3655. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3646-3655.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bi W, Ohyama T, Nakamura H. et al. Inactivation of Rai1 in mice recapitulates phenotypes observed in chromosome engineered mouse models for Smith-Magenis syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14(8):983–995. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walz K, Paylor R, Yan J, Bi W, Lupski J R. Rai1 duplication causes physical and behavioral phenotypes in a mouse model of dup(17)(p11.2p11.2) J Clin Invest. 2006;116(11):3035–3041. doi: 10.1172/JCI28953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Girirajan S, Elsea S H. Abnormal maternal behavior, altered sociability, and impaired serotonin metabolism in Rai1-transgenic mice. Mamm Genome. 2009;20(4):247–255. doi: 10.1007/s00335-009-9180-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ricard G, Molina J, Chrast J. et al. Phenotypic consequences of copy number variation: insights from Smith-Magenis and Potocki-Lupski syndrome mouse models. PLoS Biol. 2010;8(11):e1000543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lacaria M, Gu W, Lupski J R. Circadian abnormalities in mouse models of Smith-Magenis syndrome: evidence for involvement of RAI1. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A(7):1561–1568. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Walz K, Spencer C, Kaasik K, Lee C C, Lupski J R, Paylor R. Behavioral characterization of mouse models for Smith-Magenis syndrome and dup(17)(p11.2p11.2) Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13(4):367–378. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lacaria M, Spencer C, Gu W, Paylor R, Lupski J R. Enriched rearing improves behavioral responses of an animal model for CNV-based autistic-like traits. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(14):3083–3096. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Carmona-Mora P, Walz K. Retinoic acid induced 1, RAI1: a dosage sensitive gene related to neurobehavioral alterations including autistic behavior. Curr Genomics. 2010;11(8):607–617. doi: 10.2174/138920210793360952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cao L, Molina J, Abad C. et al. Correct developmental expression level of Rai1 in forebrain neurons is required for control of body weight, activity levels and learning and memory. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(7):1771–1782. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu N, Ming X, Xiao J. et al. TBX6 null variants and a common hypomorphic allele in congenital scoliosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(4):341–350. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]