Abstract

Context

Satisfaction among both physicians and patients is optimal for the delivery of high-quality healthcare. Although some links have been drawn between physician and patient satisfaction, little is known about the degree of satisfaction congruence among physicians and patients living and working in geographic proximity to each other.

Objective

We sought to identify patients and physicians from similar geographic sites and to examine how closely patients’ satisfaction with their overall healthcare correlates with physicians’ overall career satisfaction in each selected site.

Methods

We undertook a cross-sectional analysis of data from 3 rounds of the Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household and Physician Surveys (1996 –1997, 1998–1999, 2000–2001), a nationally representative telephone survey of patients and physicians. We studied randomly selected participants in the 60 CTS communities for a total household population of 179,127 patients and a total physician population of 37,238. Both physicians and patients were asked a variety of questions pertaining to satisfaction.

Results

Satisfaction varied by region but was closely correlated between physicians and patients living in the same CTS sites. Physician career satisfaction was more strongly correlated with patient overall healthcare satisfaction than any of the other aspects of the healthcare system (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient 0.628, P < 0.001). Patient trust in the physician was also highly correlated with physician career satisfaction (0.566, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Despite geographic variation, there is a strong correlation between physician and patient satisfaction living in similar geographic locations. Further analysis of this congruence and examination of areas of incongruence between patient and physician satisfaction may aid in improving the healthcare system.

Keywords: physician satisfaction, patient satisfaction, patient-physician interactions, healthcare reform, patient surveys, physician surveys

In the past few decades, the U.S. healthcare system has undergone a major metamorphosis. As the system continues its transformation, each permutation creates new struggles to control costs, minimize errors, centralize management, increase efficiency, and avoid risk. This tumultuous environment, in part, has fueled rising physician discontent.1–11 Dissatisfaction among physicians negatively impacts patients. Dissatisfied physicians have aberrant prescribing patterns.12,13 Patients of unhappy doctors are less likely to adhere to necessary medical regimens.14–17 Dissatisfied patients are also more likely to switch doctors, interrupting continuity of care and contributing to duplication of costly services.18 Satisfied physicians, on the other hand, are more attentive to patients and less likely to leave practice.8,19–22 Continuity of care, access to health information, and patient compliance are linked to quality care and better health outcomes.14,23–27

Abundant evidence suggests that physician satisfaction is optimal for the delivery of quality healthcare, so the growing body of literature that purports an increase in dissatisfaction among doctors has raised concern.1–9,28,29 Recent studies have shown that physician dissatisfaction is significantly associated with a perceived inability to obtain medically necessary services for patients, a lack of freedom to make clinical decisions, inadequate time to spend with patients, and being unable to maintain ongoing relationships with patients.6,8,11,30 Patient dissatisfaction has been linked to perceptions of physician incompetence31 and poor quality healthcare.18,25,32–35 Less is known, however, about how closely physician and patient satisfaction correlate.

To our knowledge, only a few studies have examined the extent to which satisfaction correlates between patients and providers.15,16,36–38 The research in this area generally has been limited to one geographic region, a single specialty group, a specific diagnosis, or a particular practice environment.15,16,37,39 Additional studies have focused primarily on nonphysician providers.38,40,41

In this report, we examined national correlations between satisfaction among U.S. patients and physicians using data drawn from the nationally representative Community Tracking Study (CTS) Household and Physician Surveys, spanning 6 years (1996 –2001). Our major study aim was to examine whether patients’ satisfaction with their overall healthcare correlates with physicians’ overall career satisfaction, by site.

Methods

Data Source

Data for this study are from 3 rounds of the CTS Household and Physician Surveys (1996–1997, 1998–1999, 2000–2001).42,43 The CTS, sponsored by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, is part of a major project by the Center for Studying Health System Change, a Washington DC-based organization affiliated with Mathematica Policy Research, Inc. The decision was made to include all 3 rounds of the CTS because similar analyses were conducted on each individual round, and the correlations found were comparable for all three.

The CTS conducts extensive telephone interviews with patients and physicians in both metropolitan and rural areas. Sample sites encompass areas ranging from high to low penetration of managed care. Populations sampled have racial and ethnic diversity, and a large range of incomes, educational backgrounds and household structures.42,43 These national surveys were thoroughly tested by the usual measures of validation. Sixty communities were randomly selected using stratified sampling with the probability of selection in proportion to a community’s size to ensure that the sample is representative of the U.S. population. The CTS also recruited an additional independently drawn sample to increase the precision of national estimates.43 For this study, we used only the data from the 60 main CTS sites.

Households were identified randomly from the selected sites. The overall cooperation rate was greater than 60%.44,45 Each of the 3 rounds surveyed approximately 60,000 people. Specific areas of inquiry included access to healthcare services, satisfaction, use of services, and insurance coverage.44 Twelve of the original 60 sites, referred to as “high-intensity sites,” were studied in further depth with site visits and survey samples large enough to draw conclusions about change in the community. Patient data from 3 rounds of the CTS Household Survey gave a total patient population of 179,127 individuals.

Data were obtained from physicians in the same 60 communities (including the 12 “high-intensity sites”).42,43 The sample included office-based and hospital-based physicians who spend at least 20 hours per week in direct patient care in the continental United States.45 Primary care physicians were oversampled. The overall physician response rate was approximately 60%.45 Physicians were asked a variety of questions about their patient population, practice type, reimbursement structure, career satisfaction, ease in obtaining needed patient services and ability to provide quality care.45 During the 3 survey rounds, telephone interviews were conducted with 37,238 physicians in the 60 sites.

Study Variables

Previous analyses of the CTS have linked physician career satisfaction to 6 related questions on the survey about overall satisfaction, clinical freedom, ease in obtaining referrals, ability to maintain continuity with patients, autonomy to make clinical decisions without negative financial consequences, and the ability to deliver high-quality care.6,8,11,30 We identified corresponding items in the household survey that have been reported to have similar links to patient satisfaction with the overall healthcare system.15,36,46 Patients responded to questions that inquired about satisfaction with their healthcare, their primary care physician, and specialists. They also were queried about trust, obtaining referrals to necessary specialists, and their perceptions of influence by insurance company rules. See Table 1 for a complete list of related physician and patient variables.

TABLE 1.

Community Tracking Survey Physician and Patient Satisfaction Variables

| Physician Satisfaction Variables (5-point Likert Scale, one 6-point scale): |

| “Thinking very generally about your satisfaction with your overall career in medicine, would you say that you are currently … (1 = very satisfied, 5 = very dissatisfied)?” |

| “I have the freedom to make clinical decisions that meet my patients needs.” (1 = strongly agree strongly, 5 = strongly disagree) |

| “It is possible to provide high quality care to all of my patients.” (1 = strongly agree strongly, 5 = strongly disagree) |

| It is possible to maintain the kind of continuing relationships with patients over time that promote the delivery of high quality care.” (1 = strongly agree strongly, 5 = strongly disagree) |

| “I can make clinical decisions in the best interests of my patients without the possibility of reducing my income.” (1 = strongly agree strongly, 5 = strongly disagree) |

| “How often are you able to obtain referrals to specialists of high quality when you think it is medically necessary?” (1 = always, 6 = never) |

| Patient satisfaction variables (5-point Likert Scale): |

| Constructed variable: Respondent’s satisfaction with overall healthcare (1 = very satisfied, 5 = very dissatisfied) |

| Constructed variables: Respondent’s satisfaction with choice of primary care physician (1 = very satisfied, 5 = very dissatisfied) |

| Constructed Variable: Respondent’s satisfaction with specialist physician(s) (1 = very satisfied, 5 = very dissatisfied) |

| (Think about the doctor you usually see when you are sick or need advice about your health …) |

| “I think my doctor is strongly influenced by health insurance company rules when making decisions about my medical care.” (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) |

| “I think my doctor may not refer me to a specialist when needed.” (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) |

| “I trust my doctor to put my medical needs above all other considerations when treating my medical problems.” (1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) |

As shown in Table 1, 11 variables were reported on a 5-point scale with 1 being very satisfied (or able to deliver/receive services) to 5 being very dissatisfied (or unable to deliver/receive services). One physician question about obtaining referrals had 6 points. In all of the 60 community sites, an aggregate site mean value was calculated for each of the 12 satisfaction variables (6 for physicians, 6 for patients). Because there were distinct differences in the range of site means for patients and physicians, the 60 site means for each variable were then ranked from 1 to 60. SPSS 14.0 with the complex samples module was used for the analysis.

Analysis

After calculating a site mean for each variable, we examined correlations between the 6 physician satisfaction variables and the 6 patient satisfaction variables. First, descriptive frequencies of satisfaction and associated variables were compared between patients and physicians, by site. Second, we ranked patient and physician site means (from 1 to 60) and then used Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients to examine bivariate correlations between the site mean ranks of patient and physician satisfaction variables. In addition, geographic information system mapping was done using ArcGIS 9.0 software to visualize the degree of geographic congruence between patient and physician satisfaction. Finally, mean ranks of patient and physician satisfaction were plotted on scatterplot graphs of the 60 communities to examine the strength of correlations by site. This study was approved by the Oregon Health and Science University Institutional Review Board (OHSU IRB Number: IRB00001578).

Results

Correlation Between Patients and Physicians in the Same Sites

A lower percentage of physicians reported overall satisfaction when compared with patients. The mean levels of physician career satisfaction ranged from 1.6957 to 2.3527 whereas patient satisfaction with their overall healthcare ranged from 1.4275 to 1.7912. Geographic illustrations of the mean levels of overall satisfaction show these differences (Fig. 1). The maps in Figure 1 with 5 equal quintiles (12 sites in each) also demonstrate how ranking each site’s physician and patient means from 1 to 60 allows for easier comparison of the 2 groups. CTS sites ranking in the top 10 for both patient and physician satisfaction included Lansing, MI; Milwaukee, WI; Minneapolis, MN; and NE Illinois. Sites with the lowest satisfaction rankings for both patients and physicians included: Miami, FL; Orange County, CA; Los Angeles, CA; and Newark, NJ. (A full table of all 60 sites and satisfaction rankings is available upon request.)

FIGURE 1.

Mean patient and physician satisfaction in the 60 Community Tracking Study sites (1 = very satisfied, 5 = very dissatisfied).

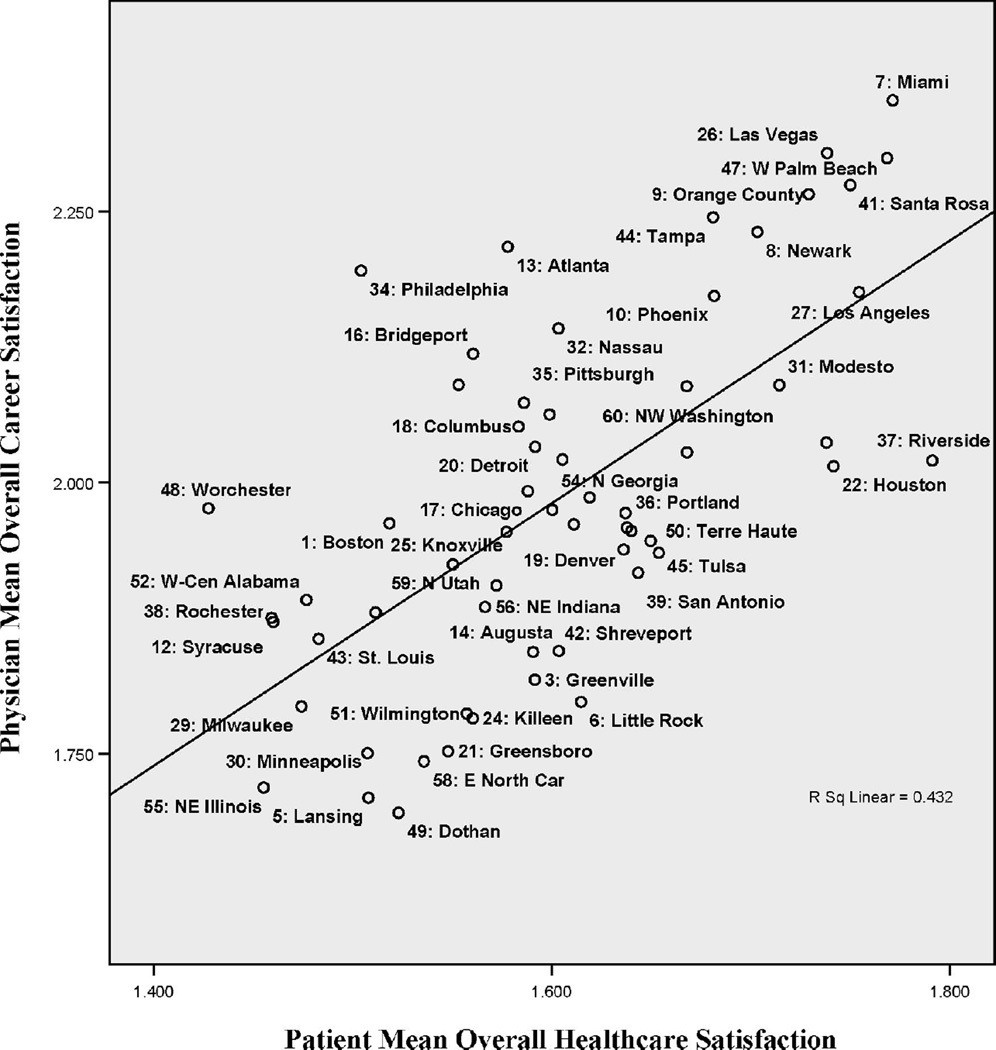

When comparing ranked site means, physician career satisfaction was more strongly correlated with patient overall healthcare satisfaction than any of the other aspects of the system as perceived by the patient (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient = 0.628, P < 0.001; see Table 2). Patient trust in the physician also was highly correlated with physician career satisfaction (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient = 0.566, P < 0.001). Similarly, when looking specifically at the strongest correlates to patient satisfaction with their overall healthcare and their doctor choice, physician career satisfaction was the highest (0.628, P < 0.001) followed by physician ability to obtain referrals (0.627, P < 0.001; see Table 2). The perceived constraints of insurance plans were less strongly correlated between patient and physician. Scatterplot graphs illustrate this strong congruence between patient overall healthcare satisfaction and physician career satisfaction, including both high and low mean levels (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Spearman’s Rank Correlations Between Patient and Physician Satisfaction in the 60 Community Tracking Study (CTS) Sites

| Patient Satisfaction Variables* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physician Satisfaction Variables* |

Patient Is Satisfied With Overall Healthcare |

Patient Is Satisfied With Choice of Primary Care Doctor |

Patient Is Satisfied With Specialist(s) |

Patient Believes Primary Care Doctor Is Influenced by Insurance |

Patient Believes Primary Care Doctor May Not Refer |

Patient Trusts Primary Care Doctor to Put Healthcare Needs Above All Other Considerations |

| Physician is satisfied with overall career |

0.628† | 0.517† | 0.499† | 0.312‡ | 0.263§ | 0.566† |

| Physician has clinical freedom to make healthcare decisions |

0.428‡ | 0.306§ | 0.231 | 0.165 | 0.041 | 0.318§ |

| Primary care physician is able to get referrals |

0.627† | 0.500† | 0.471† | 0.310§ | 0.228 | 0.574† |

| Physician can provide high quality care |

0.491† | 0.371‡ | 0.361‡ | 0.335‡ | 0.331§ | 0.418‡ |

| Physician is able to maintain patient care continuity |

0.396‡ | 0.380‡ | 0.322§ | 0.331§ | 0.139 | 0.538† |

| Physician believes clinical decisions are not affected by financial penalties |

0.304§ | 0.229 | 0.145 | 0.116 | 0.028 | 0.377‡ |

Refer to Table 1 for full description of CTS physician and patient variables that relate to satisfaction.

P < 0.001 (2-tailed).

P < 0.01 (2-tailed).

P < 0.05 (2-tailed).

FIGURE 2.

Correlations between patient and physician satisfaction in the 60 community tracking study sites.

Comparisons using data from only the 12 “high-intensity” sites showed even stronger correlations between the ranked means of physician career satisfaction and patient satisfaction with their overall healthcare (Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient 0.796, P = 0.002, figure not shown).

Discussion

The results of this study suggest geographic correlations between patient and physician satisfaction in CTS sites across the U.S. Furthermore, physician overall career satisfaction is more strongly correlated with patient overall healthcare satisfaction than any of the other associated CTS variables.

We may not know whether physician forces directly cause patient satisfaction, if patient forces contribute to physician satisfaction, or if it is other external environmental factors that strongly influence them both. Regardless of how the cascade begins, satisfaction among both patients and physicians is a key element in healthcare delivery, and triggering a cycle of dissatisfaction can lead to a worsening of many aspects in the healthcare system.

This study highlights interesting questions for future research. For example, what is driving higher rates of satisfaction among both patients and physicians in some sites, compared with others? And, why are there a few outlying sites of incongruence where the levels of patient healthcare satisfaction do not correlate with physician career satisfaction? Further studies might focus on the supply of physician services and differing penetration of managed care as well as other key demographic factors unique to these communities, such as mean age, general health status, educational background, employment figures, and household income. Another area for exploration may be the relationship between satisfaction and malpractice insurance costs and tort reform laws in certain states. Identification of unique characteristics in the geographic outliers of incongruence between patient and physician satisfaction may provide clues to other possible contributing factors. Further analysis should also focus on changes in satisfaction as new policies are implemented and whether patient and physician satisfaction are trending in different directions.

Study Limitations

As in all self-reported surveys, responses in the CTS are subject to reporting error and response bias not accounted for by statistical adjustments. Our correlation findings are associations between variables and do not establish causal relationships. Although the CTS included the same 60 sites in each of the 3 survey waves, it did not survey the same people each time, and the patients and doctors are not matched. Therefore, our results are ecological as we are not able to follow individual trends over time, and we cannot confirm that the happiest doctors in this survey are taking care of the happiest patients.

Conclusions

One of the strengths of this study is that it brings a unique perspective to discussions about how to identify some of the potential factors that may be contributing to both physician and patient satisfaction. It also highlights the potential for links between physician discontent and barriers to delivering high quality care. Is it dissatisfaction that causes lower quality or lower quality that fuels dissatisfaction? Perhaps it is the former, and satisfied physicians actually make fewer errors, leading to safer practice. Thus, satisfaction may be central to discussions about promoting quality and improving patient safety.47–50 According to David Mechanic, “Increasing understanding that quality of care is embodied in systems as well as in the efforts of conscientious and well-motivated individuals and that improving quality is a collective challenge requiring collaborations”1 (p. 945).

Both physicians and patients care about achieving quality healthcare. Physician career satisfaction is highly correlated with patient healthcare satisfaction and choice of doctor. Examining levels of satisfaction and correlations between patients and physicians provides a unique barometer to measure the health of the healthcare system.

Acknowledgments

This project was initiated at the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care as part of Dr. DeVoe’s postdoctoral fellowship, funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (F32 HS01465-02). The authors wish to acknowledge Dr. Robert Phillips, Director of the Robert Graham Center, for providing ideas and facility support for the project. No direct financial support was provided for this specific study. The first author had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mechanic D. Physician discontent: challenges and opportunities. JAMA. 2003;290:941–946. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.7.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zuger A. Dissatisfaction with medical practice. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:69–75. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr031703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassirer JP. Doctor discontent. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1543–1545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811193392109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Campion EW. A symptom of discontent. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:223–225. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leigh JP, Kravitz RL, Schembri M, et al. Physician career satisfaction across specialties. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1577–1584. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.14.1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Landon BE, Reschovsky J, Blumenthal D. Changes in career satisfaction among primary care and specialist physicians, 1997–2001. JAMA. 2003;289:442–449. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.4.442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mello MM, Studdert DM, DesRoches CM, et al. Caring for patients in a malpractice crisis: Physician satisfaction and quality of care. Health Affairs. 2004;23:42–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.4.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoddard JJ, Hargraves JL, Reed M, et al. Managed care, professional autonomy, and income - Effects on physician career satisfaction. J General Intern Med. 2001;16:675–684. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01206.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hadley J, Mitchell JM, Sulmasy DP, et al. Perceived financial incentives, HMO market penetration, and physicians’ practice style and satisfaction. Health Services Res. 1999;34:307–321. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Williams R, Willard H, Synderman R. Personalized health planning. Science. 2003;300:549. doi: 10.1126/science.300.5619.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Devoe J, Fryer GE, Hargraves JL, et al. Does career dissatisfaction affect the ability of family physicians to deliver high-quality patient care? J Family Pract. 2002;51:223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melville A. Job satisfaction in general practice: implications for prescribing. Soc Sci Med. 1980;14A:495–499. doi: 10.1016/0160-7979(80)90050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grol R, Mokkink H, Smits A, et al. Work satisfaction of general practitioners and the quality of patient care. Family Pract. 1985;2:128–135. doi: 10.1093/fampra/2.3.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DiMatteo MR, Sherbourne CD, Hays RD, et al. Physicians’ characteristics influence patients’ adherence to medical treatment: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Health Psychol. 1993;12:93–102. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.12.2.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, et al. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J General Intern Med. 2000;15:122–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.02219.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Linn LS, Brook RH, Clark VA, et al. Physician and patient satisfaction as factors related to the organization of internal medicine group practices. Med Care. 1985;23:1171–1178. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198510000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kerse N, Buetow S, Mainous AG, et al. Physician-patient relationship and medication compliance: a primary care investigation. Ann Family Med. 2004;2:455–461. doi: 10.1370/afm.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubin HR, Gandek B, Rogers WH, et al. Patients’ ratings of outpatient visits in different practice settings: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. J Am Med Assoc. 1993;270:835–840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lichtenstein R. The job satisfaction and rentention of physicians in organized settings: literature review. Med Care Rev. 1984;41:139–179. doi: 10.1177/107755878404100301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mick SS, Sussman S, Anderson-Selling L, et al. Physician turnover in eight New England prepaid group practices: an analysis. Med Care. 1983;21:323–337. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Misra-Hebert AD, Kay R, Stoller JK. A review of physician turnover: Rates, causes, and consequences. Am J Med Quality. 2004;19:56–66. doi: 10.1177/106286060401900203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Landon BE, Reschovsky JD, Pham HH, et al. Leaving medicine: the consequences of physician dissatisfaction. Med Care. 2006;44:234–242. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000199848.17133.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Garrity TF, Haynes RB, Mattson ME, et al. Medical Compliance and the Clinical-Patient Relationship: A Review. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren XS, Kazis LE, Lee A, et al. Identifying patient and physician characteristics that affect compliance with antihypertensive medications. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2002;27:47–56. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2710.2002.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Linn MW, Linn BS, Stein SR. Satisfaction with ambulatory care and compliance in older patients. Medical Care. 1982;20:606–614. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saultz JW, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Ann Family Med. 2004;2:445–451. doi: 10.1370/afm.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mainous AG, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Patient-physician shared experiences and value patients place on continuity of care. Ann Family Med. 2004;2:452–454. doi: 10.1370/afm.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz R, Scheckler WE, Moberg DP, et al. Changing nature of physician satisfaction with health maintenance organization and fee-for-service practices. J Family Pract. 1997;45:321–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Murphy J, Chang H, Montgomery JE, et al. The quality of physician-patient relationships—Patients’ experiences 1996–1999. J Family Pract. 2001;50:123–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haas JS. Physician discontent—a barometer of change and need for intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:496–497. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007496.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mikasa G, Kim SH, Ikusaka M, et al. Factors that influence physician and patient satisfaction in the outpatient setting. Paper presented at: Seventeenth World Conference of Family Doctors; Orlando, FL. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cleary PD, Edgmann-Levitan S. Health care quality: incorporating consumer perspectives. JAMA. 1997;15:42–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Q. 1966;44(Suppl 3):166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cleary PD, McNeil BJ. Patient satisfaction as an indicator of quality care. Inquiry. 1988;25:25–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harris LE, Swindle RW, Mungai SM, et al. Measuring patient satisfaction for quality improvement. Med Care. 1999;37:1207–1213. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haas JS, Phillips KA, Baker LC, et al. Is the prevalence of gatekeeping in a community associated with individual trust in medical care? Med Care. 2003;41:660–668. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000062703.14190.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Forrest CB, Shi L, von Schrader S, et al. Managed care, primary care, and the patient-practitioner relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17:270–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vahey DC, Aiken LH, Sloane DM, et al. Nurse burnout and patient satisfaction. Med Care. 2004;42(2 Suppl):II-57–II-66. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000109126.50398.5a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grembowski D, Paschane D, Diehr P, et al. Managed care, physician satisfaction, and the quality of primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:271–277. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.32127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weisman CS, Nathanson CA. Professional satisfaction and client outcomes. Med Care. 1985;23:1179–1193. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198510000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leiter M, Harvie P, Frizzell C. The correspondence of patient satisfaction and nurse burnout. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:1611–1617. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kemper P, Blumenthal D, Corrigan JM, et al. The design of the Community Tracking Study: a longitudinal study of health system change and its effects on people. Inquiry. 1996;33:195–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Metcalf CE, Kemper P, Kohn LT. Site Definition and Sample Design for the Community Tracking Study (Technical Publication no. 1) Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Strouse R, Carlson B, Hall J. Community Tracking Study Household Survey Round 3 Survey Methodology Report (Technical Publication no. 46) Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Diaz-Tena N, Potter F, Strouse R, et al. Community Tracking Study Physician Survey Round 3 Survey Methodology Report (Technical Publication no. 38) Washington, DC: Center for Studying Health System Change; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kao AC, Green DC, Davis NA, et al. Patients’ trust in their physicians: effects of choice, continuity, and payment method. J Gen Intern Med. 1998;13:681–686. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1998.00204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Connor JP, Nash DB, Buehler ML, et al. Satisfaction higher for physician executives who treat patients, survey finds. Phys Executive. 2002;28:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dunstone DC, Reames HR Jr. Physician satisfaction revisited. Soc Sci Med. 2001;52:825–837. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00186-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, editors. To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]