Abstract

The objective of our study was to determine the mechanism of action of the short-chain ceramide analog, C6-ceramide, and the breast cancer drug, tamoxifen, which we show coactively depress viability and induce apoptosis in human acute myelogenous leukemia cells. Exposure to the C6-ceramide-tamoxifen combination elicited decreases in mitochondrial membrane potential and complex I respiration, increases in reactive oxygen species (ROS), and release of mitochondrial proapoptotic proteins. Decreases in ATP levels, reduced glycolytic capacity, and reduced expression of inhibitors of apoptosis proteins also resulted. Cytotoxicity of the drug combination was mitigated by exposure to antioxidant. Cells metabolized C6-ceramide by glycosylation and hydrolysis, the latter leading to increases in long-chain ceramides. Tamoxifen potently blocked glycosylation of C6-ceramide and long-chain ceramides. N-desmethyltamoxifen, a poor antiestrogen and the major tamoxifen metabolite in humans, was also effective with C6-ceramide, indicating that traditional antiestrogen pathways are not involved in cellular responses. We conclude that cell death is driven by mitochondrial targeting and ROS generation and that tamoxifen enhances the ceramide effect by blocking its metabolism. As depletion of ATP and targeting the “Warburg effect” represent dynamic metabolic insult, this ceramide-containing combination may be of utility in the treatment of leukemia and other cancers.

Keywords: ceramides, sphingolipids, leukemia, mitochondria

The bioactive, tumor suppressor sphingolipid ceramide (1–3), which plays a central role in initiating cancer cell death (4, 5), can be of unique utility from a therapeutic standpoint (6). Many drugs used in the treatment of cancer are themselves ceramide generators, a property that contributes in part to their apoptosis-inducing effects (7). Once generated, however, cancer cells can convert ceramide to higher sphingolipids, notably glucosylceramide (GC), blunting ceramide’s anticancer benefits (1, 8). As upregulated ceramide glycosylation is linked with multidrug resistance, limiting ceramide glycosylation would appear to be an appropriate intervention, a scenario that has been demonstrated in past works (9, 10). In addition to glycosylation, ceramide metabolism via hydrolysis gives rise to sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1-P), a mitogenic sphingolipid that competes with ceramide’s proapoptotic effects (11, 12).

Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) is the most common type of leukemia in adults. Only ∼25% of patients who experience remission with cytotoxic chemotherapy remain disease free. Therapy for these patients generally consists of cytosine arabinoside plus anthracycline, a regimen that has been in use for more than three decades; thus, there exists a critical need to develop more effective therapies in AML. One novel approach involves the use of C6-ceramide, a ceramide mimic, which like its long-chain, natural counterpart has tumor-suppressor properties. An innovative feature presented herein, however, is the inclusion of the breast cancer drug tamoxifen, which we show magnifies the C6-ceramide effect in AML, and the use of C6-ceramide-tamoxifen nanoliposomes, composites that deliver both agents within the same particle.

Although tamoxifen has long been utilized as a modulator of multidrug resistance, similar to verapamil and cyclosporin A, the impact of tamoxifen on sphingolipid metabolism has only more recently been demonstrated. Apropos in this context, tamoxifen can suppress ceramide metabolism via glycosylation (13) and inhibit hydrolysis (14), thus reducing S1-P formation (15). Therefore, when used in combination with a cell-deliverable ceramide, such as C6-ceramide, or ceramide-generating drugs, beneficial actions from a therapeutic standpoint can be realized.

The development of ceramide-based therapy in cancer treatment is promising (6). In earlier work in HL-60/VCR cells, we demonstrated that tamoxifen enhanced the cytotoxicity of fenretinide, a ceramide-generating retinoid (16), and C6-ceramide; however, mechanisms supporting this enhancement had not been elucidated (15). Herein, we demonstrate that the mechanisms promoting C6-ceramide-tamoxifen cytotoxicity in AML cells encompass a reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential, inhibition of complex I respiration, generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), reduced glycolytic capacity, and decreases in ATP. Significant players in AML cell survival were also targeted, XIAP and survivin, members of the inhibitors of apoptosis protein (IAP) family. As glycolysis is an important cell-sustaining maneuver in cancer, this unique C6-ceramide-tamoxifen combination, which imparts substantial bioenergetic clout, could constitute an effective therapy in AML. Of note, N-desmethyltamoxifen (DMT), the primary tamoxifen metabolite in humans with little antiestrogenic activity, was as effective as tamoxifen, demonstrating that we are not working through traditional antiestrogen pathways.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

AML cell lines

Human AML cell lines KG-1 and HL-60 were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). HL-60/VCR cells were provided by A. R. Safa (Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN) and were grown in medium containing 1.0 μg/ml vincristine. Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) with 10% FBS (Atlanta Biologicals, Atlanta, GA), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. For experiments with HL-60/VCR cells, vincristine was removed from the medium. Cells were cultured in a humidified atmosphere, 95% air, 5% CO2, at 37°C.

Patient samples

AML patient samples with 20% or greater blast count were collected with signed informed consent according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Milton S. Hershey Medical Center. Human granulocyte-colony stimulating factor mobilized peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy donors were obtained from the Blood Bank (Milton S. Hershey Medical Center). PBMCs were enriched using the Ficoll-Paque gradient separation method (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

Reagents

C6-ceramide was from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Propidium iodide (PI), JC-10 mitochondria kit, α-tocopherol (vitamin E), tamoxifen, and DMT were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). C6-ceramide, tamoxifen, and DMT were dissolved in DMSO (10 mM stock solutions) and stored at −20°C. MitoSOXTM Red, Pierce™ Protease Inhibitor cocktail (EDTA free), and HBSS were from Life Technologies.

Cell viability assays

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates (0.5 × 106 cells/well, 5% FBS medium, 2.0 ml final volume), treated with indicated agents for times designated, collected by centrifugation, washed with PBS, and suspended in 0.1 ml PI buffer [PBS, pH 7.4, 50 μg/ml PI, 0.2% BSA (BSA)] for 10 min. PI-positive cells were determined by flow cytometry (Becton Dickinson FACS Calibur); data were assessed using FCS Express 4, De Novo Software (Glendale, CA). Viability was also determined using the CellTiter 96 Assay Kit (MTS) (Promega, Milwaukee, WI), according to instructions. Viability was calculated as the mean (n = 3 or n = 6) absorbance (minus vehicle control) at 490 nm, using a Bio-Tek Synergy H1 microplate reader.

Nanoliposomes

Pegylated nanoliposomes were prepared from specific lipids at particular molar ratios as previously described (17, 18). Briefly, 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine, 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine, 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000], and C6-ceramide (or tamoxifen) were dissolved in chloroform, dried to a film under a stream of nitrogen, and then hydrated by addition of 0.9% NaCl. Solutions were sealed, heated at 55°C for 60 min, vortex mixed, and sonicated for 5 min until light no longer diffracted through the suspension. The solution was quickly extruded at 55°C by passage through 100 nm polycarbonate filters in an Avanti Mini-Extruder (Avanti Polar Lipids). Ghost nanoliposomes were prepared in the same manner excluding C6-ceramide. Composite nanoliposomes were formulated as above, using C6-ceramide and tamoxifen.

Apoptosis assay

Apoptosis was assessed using the ApoDETECT Annexin V-FITC Kit (Life Technologies) as previously described, to detect annexin V binding by flow cytometry (15).

Caspase-3 activation

Caspase-3 proteolytic activity was measured using the Caspase-3 DEVD-R110 Fluorometric HTS Assay Kit (Biotium Inc., Hayward, CA), per manufacturer’s instructions.

Mitochondrial respiration

High-resolution O2 consumption measurements were conducted at 30°C in Mir05 (110 mM sucrose, 0.5 mM EGTA, 60 mM K-lactobionate, 3 mM MgCl2-6H2O, 20 mM taurine, 10 mM KH2PO4, 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.1, 1 mg/ml BSA) using the OROBOROS O2K Oxygraph (Innsbruck, Austria). HL60/VCR (2 × 106 cells/chamber) and KG-1 (4 × 106 cells/chamber) were added to the respirometer and permeabilized with digitonin (4 μg and 3 μg/106 cells for HL60/VCR and KG-1 cell lines, respectively). Optimal permeabilization was determined by titration of digitonin in the presence of maximal substrate (glutamate, malate, ADP). Substrate inhibitor titration protocol was conducted as follows: 2 mM malate + 10 mM glutamate (complex I supported state 2 respiration), followed by the addition of 4 mM ADP to initiate state 3 respiration supported by complex I substrates. Convergent electron flow was initiated by addition of 10 mM succinate, and 10 μM rotenone was subsequently added to inhibit complex I, followed by 10 μM cytochrome c to test the integrity of the outer mitochondrial membrane, and finally, uncoupled respiration was assessed with the addition of 0.5 μM carbonyl cyanide-4-(trifluoromethoxy)phenylhydrazone. The rate of respiration, oxygen consumption, was calculated as pmol/s/106 cells and expressed as a percentage of control (DMSO treated) cells.

Mitochondria membrane potential ΔΨm

To detect changes in mitochondrial ΔΨm after long-term treatment, cells were stained with JC-10 dye. Assays were conducted according the manufacturer’s instructions. To assess alterations in mitochondrial ΔΨm after short-term exposure to drugs, KG-1 cells (2 × 106) were preincubated in 2 ml of a JC-10 dye loading solution (HBSS containing 20 µl JC-10) for 15 min. Cells were then washed in HBSS containing 0.1% BSA, suspended in FBS-free RPMI-1640 medium containing 0.1% BSA, and a 0.1 ml aliquot was added to wells of a 96-well plate. Cells were treated by adding 0.1 ml of a 2× drug solution (C6-ceramide-tamoxifen, in RPMI-1640 medium, 0.1% BSA) to achieve the desired drug concentration. Plates were read at excitation/emission wavelengths 490/525 and 540/590 nm using a microplate reader.

Mitochondrial ROS

Mitochondrial superoxide was assayed using MitoSOXTM Red. Cells (1 × 106/2 ml 5% FBS RPMI-1640 medium) were seeded in 6-well plates, treated with indicated agents for 24 h, then washed in HBSS and incubated in 0.25 ml staining buffer (HBSS containing 5 μM MitoSOX) for 15 min at 37°C. Cells were washed in HBSS, resuspended at 1 × 106/ml HBSS, and a 0.1 ml aliquot was added to the wells of a 96-well plate. Fluorescence was measured at 510 nm excitation and 580 nm emission.

ATP/ADP analysis by HPLC

Cells were collected, isolated by centrifugation, and deproteinated on ice by the addition of 0.5 N perchloric acid for 10 min. Extracts were neutralized on ice for 10 min with 1N KOH at a ratio of 2:1. HPLC was used to quantitate cellular ATP and ADP (19), using a Shimadzu Prominence HPLC system equipped with a Purospher STAR RP-18 end-capped column (4.6 × 150 mm 3 μm, EMD Millipore) at flow rate of 0.4 ml/min with a column temperature of 37°C.

ATP end-point assay

Cells were collected and lysed by sonication in 1 ml buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Triton X-100. Samples were heated to 95°C for 5 min and centrifuged at 500 g for 10 min at 4°C to remove debris. Concentrations of Mg-ATP in supernatants were determined using the hexokinase/glucose-6-phosphate coupled assay (20). The reduction of NADP+ to NADPH was monitored at 340 nm (ε340 = 6,200 cm−1 M−1). All reactions were determined at 25°C in 1 ml containing 50 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5), 5 mM MgCl2, 50 mM glucose, 1 mM NADP+, 0.5 units hexokinase, and 5 units glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and initiated by addition of 50 µl of cell lysate.

Glycolysis

Cells were seeded into an XF assay microplate (Seahorse Bioscience, North Billerica, MA). The assay cartridge was hydrated overnight, at 37°C, in a CO2-free incubator. On the day of assay, the treatment medium was discarded, and assay medium (Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium, Life Technologies) containing 1.85 g/l NaCl, 3 mg/l phenol red, and 2 mM l-glutamine was added. Alterations in the extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) were measured with the XF24 Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer. Results were normalized based on the number of live cells at assay time.

Cytochrome c release

Cytochrome c release from mitochondria was assessed as described (21). Cells (2 × 106/2 ml 2.5% FBS RPMI-1640 medium) were seeded in 6-well plates and treated with agents for 18 h, after which 1 × 106 cells were removed and placed on ice with 0.1 ml of digitonin (100 μg/ml in PBS, 100 mM KCl) for 3–5 min until 95% of the cells were permeabilized (stained positive with 0.2% trypan blue). Cells were then fixed at room temperature in 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 20 min and resuspended in blocking buffer (PBS, 3% BSA, 0.05% saponin). Fixed cells were incubated for 30 min at 4°C in a 1:100 dilution of FITC conjugate (6H2) anti-cytochrome c antibody (Life Technologies) in blocking buffer and washed, and levels of cytochrome c were determined. Cell acquisition was performed on a Becton Dickinson FACSCalibur. Analysis was performed using FCS Express 4 from De Novo Software.

SMAC and IAP analysis

RIPA buffer and antibodies were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase (SMAC) release was performed as described (22) with modifications. After treatment, KG-1 cells were harvested in RIPA buffer supplemented with 1 mM PMSF, centrifuged, washed in PBS, and suspended in 0.2 ml of ice-cold buffer A [250 mM sucrose, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM PMSF, 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.5)] containing protease inhibitor cocktail, for 15 min followed by addition of digitonin to a final concentration of 200 µg/ml. Samples were mixed for 30 s, and permeabilization of cells was confirmed by staining with 0.2% trypan blue. Cells were centrifuged at 16,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant (cytosolic fraction) was retained, and the pellets were washed with buffer A, without digitonin. After centrifugation (16,000 g, 5 min), pellets containing mitochondria were solubilized in mitochondrial lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 0.2% Triton X-100, 0.3% NP-40) containing protease inhibitor cocktail, followed by centrifugation (16,000 g, 5 min, 4°C). The supernatants (solubilized mitochondria) were retained for analysis. Protein in cellular lysates, cytosolic fractions, and solubilized mitochondria was measured using a BCA Protein Assay Kit. Equal amounts of protein were loaded onto 4%–12% NuPAGE gels (Invitrogen) for electrophoresis. Protein was transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and probed with antibodies against SMAC, survivin, XIAP, voltage-dependent anion channel, and β-actin. Blots were imaged using a LI-COR Biosciences Odyssey Infrared Fluorescent scanner (Lincoln, NE).

MS

Total lipids were extracted from cells using ethyl acetate-isopropanol-water (60:30:10, v/v) without phase partitioning, and the solvents were evaporated (azeotroph) under a stream of nitrogen. Internal standards were added, and separations were conducted using electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-ESI-MS/MS, using a Waters I-class Acquity LC and the Waters Xevo TQ-S mass spectrometer, as previously described (23).

Statistical analysis

The results are expressed as the mean ± SE and were analyzed by ANOVA. Differences among treatment groups were assessed by Tukey’s test. Differences were considered significant at P ≤ 0.05. An asterisk (*) used in specific figures denotes significance. Replicates ranged from n = 3 to n = 6, and repeated experiments yielded similar results.

RESULTS

Combination C6-ceramide-tamoxien is cytotoxic in AML, inducing apoptotic cell death; cytotoxicity reversed by antioxidant

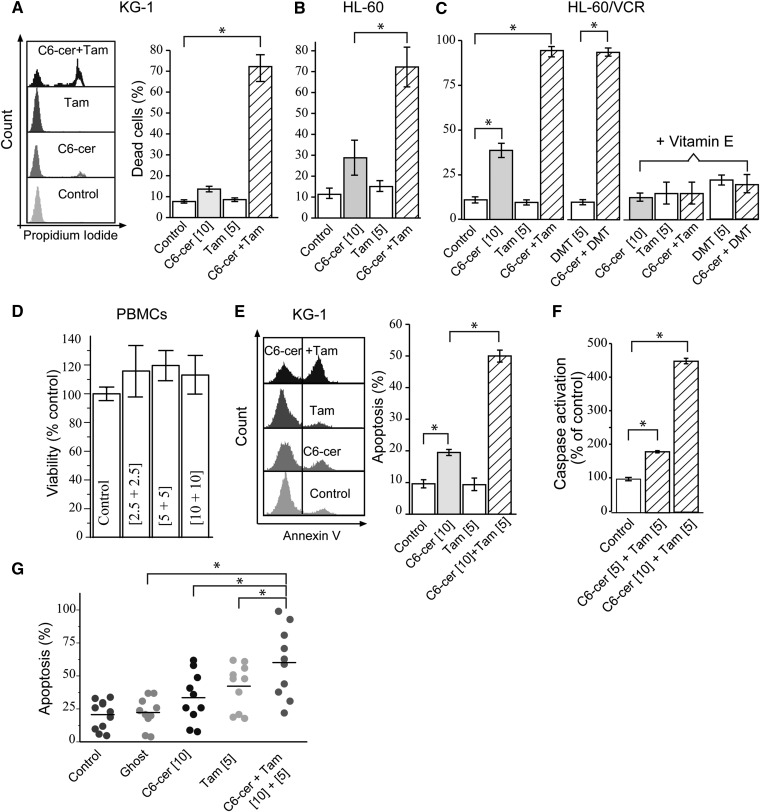

The C6-ceramide-tamoxifen regimen was active in three cell lines, KG-1, HL-60, and HL-60/VCR, and in patient-derived AML cells. The interdependent activity of this regimen is illustrated in Fig. 1A–C, which shows that exposure to C6-ceramide yielded only slight but significant responses in HL-60 and in HL-60/VCR cells and produced no response in KG-1 cells. However, whereas tamoxifen was without significant impact in all cell lines, the combination resulted in 70% or greater cell death. Moreover, the regimen was effective in multidrug-resistant HL-60/VCR cells (Fig. 1C), and DMT, the most prominent tamoxifen metabolite in humans having <1% of the antiestrogenic activity of tamoxifen (24), was as effective as tamoxifen when combined with C6-ceramide. Noteworthy, the addition of antioxidant vitamin E totally mitigated cytotoxicity. The regimen was not cytotoxic in PBMCs (Fig. 1D). Treatment of KG-1 cells with the combination promoted significant increases over single agents in annexin V binding (Fig. 1E) and elicited dose-dependent caspase activation (Fig. 1F). Similar responses were observed in HL-60 and HL-60/VCR cells (data not shown). The regimen also induced apoptosis in AML cells derived from patients (Fig. 1G, left). In this experiment, nanoliposomal formulations of C6-ceramide and tamoxifen were used, as this would be the preferred mode of in vivo administration. Approximately 50% of patients demonstrated strong apoptotic response to the C6-ceramide-tamoxifen regimen. The disparate distribution in responses is perhaps reflective of the heterogeneity in AML and the difficulties inherent in treating this disease.

Fig. 1.

Combination C6-ceramide-tamoxifen and C6-ceramide-DMT are cytotoxic in AML but not in PBMCs; cytotoxicity reversed by vitamin E. A–C: Cytotoxicity in KG-1, HL-60, and HL-60/VCR cells and reversibility by vitamin E. Specified cell lines were seeded into 96-well plates, pretreated with either tamoxifen of DMT for 1 h before addition of C6-ceramide, and incubated for 48 h. Where noted in C, cells were preincubated with vitamin E (250 µM final concentration) for 2 h before addition of drugs. Cytotoxicity was evaluated by PI staining using flow cytometry; cell gating is shown by histogram in A. D: Effect of nanoliposomal regimen on PBMC viability. PBMCs were seeded as above and treated with the agents indicated for 48 h (equimolar concentrations of nanoliposomal C6-ceramide and nanoliposomal tamoxifen were administered); viability was measured by MTS assay. E: Effect of combination regimen on apoptosis in KG-1 cells. Left, flow cytometry histogram; right, apoptosis quantitation. Cells were treated for 24 h. Annexin binding was used to quantitate apoptosis. F: Caspase-3 activation in KG-1 cells. Cells were treated for 18 h. G: Induction of apoptosis in patient-derived AML cells. Annexin binding was used to measure apoptosis; n = 10 patients. Nanoliposomal formulations of the agents were used. For all panels, micromolar concentrations of agents are given in brackets. Different time points were used in experiments A–G, to maximize detection of optimal activity. In A–D, data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments; n = 6 replicates per experiment. In E and F, data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. * P ≤ 0.05, one-way ANOVA.

C6-ceramide-tamoxifen selectively targets mitochondrial complex I respiration and promotes production of mitochondrial ROS

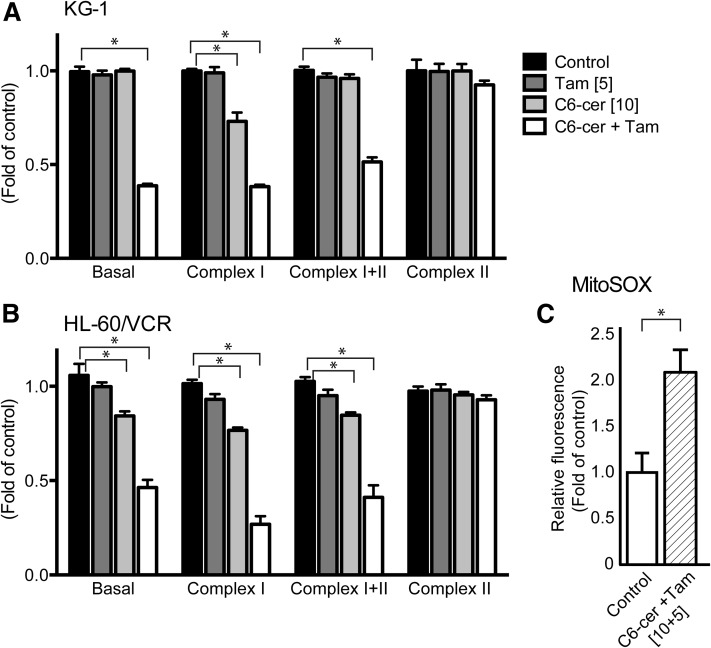

Of the emerging areas in cancer therapy, mitochondria have been the object of much attention (25). As mitochondria play crucial roles in generation and maintenance of cellular energy and redox charge, we investigated the impact of C6-ceramide and tamoxifen on bioenergetics. Treatment of KG-1 and HL-60/VCR cells with the combination as opposed to the single agents decreased basal (nonphosphorylating, state 4) respiration by ∼50%, and maximal (phosphorylation under conditions with saturating [ADP], state 3) respiration supported by complex I (glutamate + malate) by ∼60%, but not complex II only (succinate in the presence of complex I inhibitor rotenone) respiration (Fig. 2A, B). Acute treatment was also evaluated in which cells were permeabilized and exposed to a higher dose regimen (20 µM C6-ceramide plus 10 µM tamoxifen) for only 20 min. Results revealed that both basal and complex I-supported respiration were decreased by 50% and 75%, respectively, in HL-60/VCR cells and by 25% and 75%, respectively, in KG-1 cells (data not shown). These data highlight a crippling reduction in respiration specifically supported by electron transfer from NADH through complex I, contributing to decreased capacity for oxidative metabolism. Inhibition of complex I has been shown to promote mitochondrial ROS production (26, 27), and as vitamin E mitigated cytotoxicity, we evaluated the levels of ROS. Exposure to the regimen produced a 2-fold increase over control in mitochondrial ROS levels (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Specific inhibition of mitochondrial complex I respiration and generation of mitochondrial ROS by combination C6-ceramide-tamoxifen in drug-sensitive and in multidrug-resistant AML cells. A: KG-1 cells. B: HL-60/VCR cells. Mitochondrial respiration was measured using the OROBOROS O2K Oxygraph, after 18 h exposure to the agents indicated. C: Mitochondrial ROS in HL-60/VCR cells. The MitoSOX assay was used, after 18 h exposure to combination C6-ceramide-tamoxifen. Micromolar drug concentrations are given in brackets. Untreated controls represented by 1.0. In A and B, data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. In C, data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments in triplicate * P ≤ 0.05, one-way ANOVA.

Regimen promotes mitochondrial membrane permeability transition and release of cytochrome c and SMAC and diminishes expression of IAP survival elements

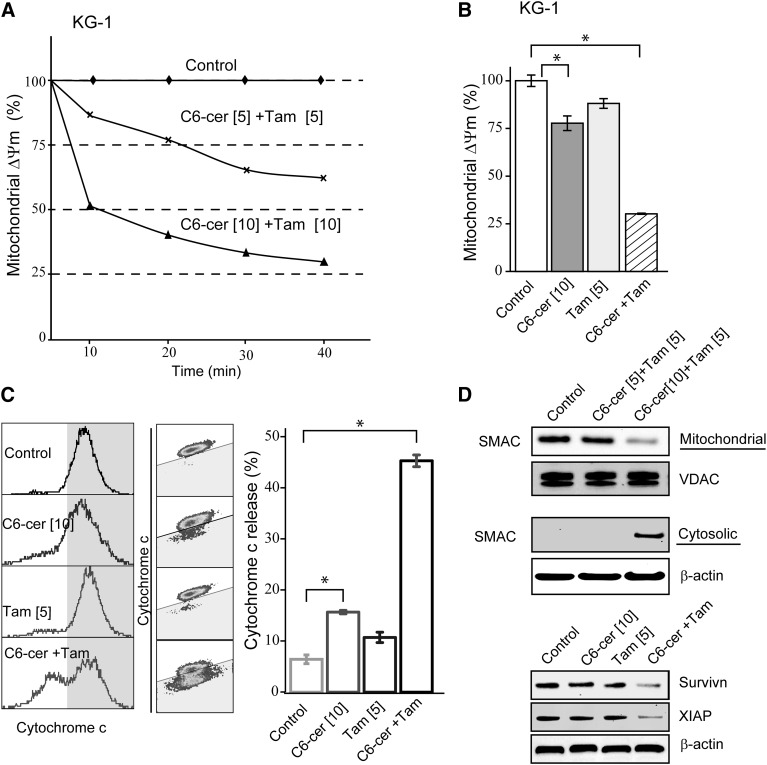

Successful apoptosis is allied with dissipation of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) that elicits transitions in mitochondrial outer membrane permeability, a process that can be accompanied by release of cytochrome c, key in downstream signaling events. Consistent with this scenario, the C6-ceramide-tamoxifen regimen induced dose- and time-dependent decreases in ΔΨm (Fig. 3A); decreases were evident as early as 10 min after exposure. Longer-term exposures showed that single agents were not as effective as the combination, which resulted in a 75% decrease in ΔΨm (Fig. 3B). Membrane permeability changes were accompanied by release of proapoptotic cytochrome c that was largely driven by the combination (Fig. 3C, left to right, histogram, density plot, bar graph). For example, whereas C6-ceramide and tamoxifen treatment resulted in cytochrome c release that was ∼9% and 6% over control, respectively, the combination produced a 40% (Fig. 3C), supporting the view that tamoxifen magnifies the effect of C6-ceramide on mitochondrial function. Exposure to the regimen also promoted release of SMAC and downregulated the expression of the IAPs survivin and XIAP (Fig. 3D), two important mediators of the intrinsic mitochondrial pathway of apoptosis. The data in Fig. 3D (top) show a dose-dependent decrease in mitochondrial SMAC accompanied by an increase in cytosolic SMAC, indicative of mitochondrial membrane permeability disruption. Moreover, survivin and XIAP were targeted more effectively with the combination regimen (Fig. 3D, bottom).

Fig. 3.

Drug regimen alters mitochondrial membrane potential, elicits release of cytochrome c and SMAC, and downregulates expression of IAP proteins in AML cells. A: Time- and dose-dependent alteration in mitochondrial ΔΨm in KG-1 cells. For the short-term effects (10–40 min), cells were preloaded with JC-10 for 10 min before addition of combination regimen, as detailed in Materials and Methods. B: Effect of C6-ceramide, tamoxifen, and the combination regimen on mitochondrial ΔΨm. Cells were treated with the indicated agents for 18 h before evaluation of mitochondrial ΔΨm. C: Effect of C6-ceramide, tamoxifen, and combination on cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Left and middle panels, results depicted by flow cytometry histograms; right panel, bar graph quantitation of cytochrome c release under specified treatment regimens. D: Effect of drug regimen (cells were treated for 24 h), on SMAC release and on survivin and XIAP expression. Upper panels, SMAC quantitation in mitochondria and cytosol (assessed by Western blot); lower panel, survivin and XIAP expression measured by Western blot. Micromolar concentrations are given in brackets. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. * P ≤ 0.05, one-way ANOVA. VDAC, voltage-dependent anion channel.

Regimen elicits robust bioenergetics insult through inhibition of glycolysis and lowering of ATP levels

Targeting mitochondria is an expedient way to disrupt the energy-producing systems of cancer cells, and we demonstrate that C6-ceramide-tamoxifen institutes a commitment to energy severance. End-point enzymology (Fig. 4A) showed that the drug regimen elicited a 50% decrease in cellular ATP levels at 24 h with a further decrease at 48 h (Fig. 4A). HPLC analyses showed that whereas C6-ceramide produced a 3-fold increase over control in the ADP to ATP ratio and tamoxifen was without influence, the combination produced a 9-fold increase in the ratio (Fig. 4B), illustrating coactive, interdependent responses to the agents. Glycolysis measurements showed a >50% reduction in the capacity to increase the ECAR when mitochondrial ATP production was blocked by oligomycin in KG-1 cells exposed to the drug regimen (Fig. 4C). Results with each agent demonstrated that the combination was more effective (Fig. 4D). In summary, inhibition of respiration (see Fig. 2) with concomitant reduction in glycolytic activity constitutes severe bioenergetics crisis.

Fig. 4.

C6-ceramide-tamoxifen combination restricts cellular ATP production and limits glycolytic capacity in AML cells. A: Effect of exposure time to combination regimen (10 µM C6-ceramide + 5 µM tamoxifen) on ATP levels in KG-1 cells. ATP was measured by end-point enzymology as detailed in Materials and Methods. B: ADP to ATP ratio in KG-1 cells in response to C6-ceramide, tamoxifen, and the combination. Quantitation was performed by HPLC. Cells were exposed for 24 h; micromolar dose is shown brackets. C: Effect of C6-ceramide-tamoxifen regimen on glycolysis. KG-1 cells were exposed to the drug regimen for 24 h and processed for analysis (carried out with the XF24 Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer, Seahorse Bioscience). Drug dosage was as in A. D: Effect of single agents and combination regimen on glycolysis. KG-1 cells were incubated with indicated agents for 24 h; glycolytic capacity was analyzed with the XF24 Seahorse extracellular flux analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience). C6-cer, C6-ceramide; Tam, tamoxifen. In A and B, data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. In D, data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments in triplicate. * P ≤ 0.05, one-way ANOVA.

Efficacy of C6-ceramide-tamoxifen multifunctional, composite nanoliposomes

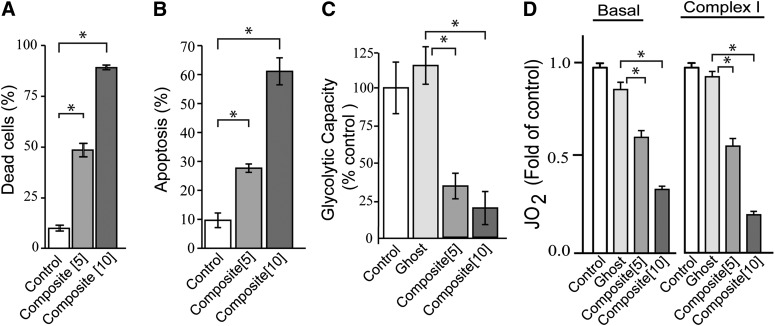

One unique feature of the nanoliposome is service as a stealth delivery vehicle for drugs and adjuvants, allowing design of novel, multifunctional therapeutics. In composite particles, the hydrophobic environment of the phospholipid fatty acyl chains allows for acquisition and accommodation of hydrophobic agents such as tamoxifen and C6-ceramide. Composite nanoliposomes (equal concentrations of C6-ceramide and tamoxifen are formulated within the same particle) were cytotoxic in HL-60/VCR cells at doses of 5 and 10 µM (Fig. 5A), elicited dose-dependent increases in apoptosis (Fig. 5B), produced a robust reduction in glycolytic activity (Fig. 5C), and limited both basal and complex I mitochondrial respiration (Fig. 5D). Thus, the nanoliposomal formulation constitutes an effective vehicle for unique delivery of the cytotoxic regimen.

Fig. 5.

Efficacy of C6-ceramide-tamoxifen composite nanoliposomes in multidrug-resistant AML cells. A: Cytotoxic effect of composite nanoliposomes. HL-60/VCR cells were incubated with composites at the micromolar concentrations indicated for 48 h; cytotoxicity was measured by PI staining and flow cytometry. B: Effect of composite nanoliposomes on apoptosis. Cells were exposed for 24 h, after which apoptosis was gauged by annexin V binding. C: Impact of composite nanoliposomes on glycolysis. Analysis was carried out by Seahorse Bioscience. D: Effect of composite nanoliposomes on mitochondrial respiration. Analysis was carried out by OROBOROS O2K Oxygraph. In C and D, cells were incubated with the nanoliposomal agents indicated (micromolar concentrations in brackets) for 24 h. C6-cer, C6-ceramide; Ghost, nanoliposome devoid of C6-ceramide and tamoxifen; Tam, tamoxifen. Composite nanoliposomes contain equal concentrations of C6-ceramide and tamoxifen within the same particle. In A–C, data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments; n = 6 replicates per experiment. In D, data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. * P ≤ 0.05, one-way ANOVA.

Cellular metabolism of C6-ceramide and the impact of tamoxifen

Inhibition of ceramide glycosylation is a novel, nongenomic activity of tamoxifen (28). We were therefore interested in investigating the influence of tamoxifen on C6-ceramide metabolism in AML, with the idea that C6-ceramide potency could be elevated by blocking anabolism. First, marked increases in the levels intracellular long-chain ceramides occurred in cells exposed to C6-ceramide, and these increases were heightened when tamoxifen was included (Fig. 6A). The ceramide molecular species produced were mainly limited to C16:0 and C24:1. Intracellular levels of C6-ceramide were significantly higher in cells in which tamoxifen was coadministered (Fig. 6B). C6-ceramide exposure also resulted in increased levels of C16:0 and C24:1 molecular species of natural GCs (Fig. 6C), presumably via glycosylation of the long-chain ceramides that were generated. Glycosylation of natural GC (C16:0 GC, C24:1 GC) and C6-GC was blocked by tamoxifen (Fig. 6C, D, respectively). These data illustrate the influential effect of tamoxifen on ceramide glycosylation in intact cells. The scheme in Fig. 6E summarizes the metabolic routes of C6-ceramide. C6-ceramide can be converted to C6-GC and C6-SM or hydrolyzed by ceramidases (29), yielding sphingosine, which can be converted to S1-P or reutilized for synthesis of long-chain ceramides via the salvage pathway. Long-chain ceramides can be converted to complex glycosphingolipids, GC for example. Tamoxifen effectively blocks glycosylation of C6-ceramide and long-chain ceramides. The generation of long-chain ceramides and their impact on cell fate are currently under investigation. Interestingly, as short-chain ceramides are poor substrates for acid ceramidase and tamoxifen downregulates acid ceramidase activity (14), the roles of alkaline and neutral ceramidases in generation of long-chain ceramides from C6-ceramide are of keen interest.

Fig. 6.

C6-ceramide metabolism in KG-1 cells and the influence of tamoxifen. A: Effect of exposure to C6-ceramide on intracellular levels of long-chain ceramides and the effects of added tamoxifen. B: Intracellular C6-ceramide levels in cells exposed to C6-ceramide and the influence of tamoxifen. C: GC formation in cells exposed to C6-ceramide and the influence of tamoxifen. D: C6-GC formation in C6-ceramide-exposed cells and the influence of tamoxifen. KG-1 cells (1 × 10 6/ml RPMI-1640 medium containing 5% FBS) were cultured with the agents indicated (micromolar concentrations given in brackets) for 24 h. Cells were harvested and lipids were extracted and analyzed by LC/MS/MS as detailed in Materials and Methods. E: Flow scheme depicting C6-ceramide metabolism and the influence of tamoxifen. C6-GC, C6-glucosylceramide; C6-SM, C6-sphingomyelin; So, sphingosine. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. * P ≤ 0.05, one-way ANOVA.

DISCUSSION

The present work shows that a sphingolipid-containing drug combination, consisting of C6-ceramide and tamoxifen, is cytotoxic and acts interdependently in inducing apoptosis in AML cell lines and in AML cells derived from patients but was without influence in isolated human PBMCs, selectivity that is important in the clinical setting. Further, DMT, the major tamoxifen metabolite in humans, which displays only 1% of the antiestrogenic activity of the parent drug (24), was effective with C6-ceramide, a clear indication that antiestrogen pathways are not involved. Use of tamoxifen in an adjuvant setting wherein high doses are needed is within the realm of clinical utility (30). Mechanistically, the regimen targets the intrinsic apoptotic pathway, initiated by permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane giving rise to cytochrome c release, which can be termed a “point of no return.” Changes in ΔΨm can result from alterations in mitochondrial respiration, and in our examination, we demonstrated that the regimen, but not tamoxifen at the administered dose, elicited inhibition of complex I respiration. In isolated liver mitochondria, tamoxifen at 25 µM has been shown to interact with the flavin mononucleotide site of complex I leading to mitochondrial failure (31). In our work, it is possible that C6-ceramide primes mitochondria for tamoxifen effects, as ceramide can elicit membrane channel formation and enhance permeability to small molecules (32, 33). Although there are many known upstream ceramide targets (5), the present study sought to focus on mitochondrial impact and downstream effectors.

Complex I inhibitors exhibit anticancer properties, and in drug screening from the National Cancer Institute, complex I inhibitors demonstrated antileukemic activity (34). Complex I is the largest and most complex enzyme of the chain, and inhibition can significantly limit the flow of electrons along the chain, promoting bioenergetic exhaustion. Inhibition of complex I also increases ROS production (26, 27, 35) and should limit ATP production, both of which were consequences of exposure to the C6-ceramide-tamoxifen regimen. Interestingly, a study by Bradbury et al (36) showed that the ADP-to-ATP ratio in human leukemia cells can be used as a measure of viability, necrosis, and apoptosis, where this ratio in viable cells was <0.11, and from 0.11 to 1.0 in cells undergoing apoptosis, a value in line with KG-1 cellular responses to the regimen. Studies with C2-ceramide in intact, isolated mitochondria revealed inhibition of complex III respiration (37), and a study by Di Paola et al (38) showed that both complex I and IV activities could be inhibited by C2-ceramide.

The C6-ceramide regimen also inhibited glycolysis. The “Warburg effect,” the ability to utilize high amounts of glucose for ATP generation, is a hallmark of cancer cells; this switch to glycolytic dependency favors less efficient generation of ATP compared with oxidative phosphorylation that prevails in normal cells. Thus, limiting glycolysis can effectively serve to disrupt bioenergetics and stress cancer cells that are dependent on glycolysis for ATP generation. Apropos in this instance is work documenting distinct glucose metabolism signatures of prognostic value in AML, stressing that glycolysis may be a potential target in AML, specifically inhibition of glycolysis for potentiation of Ara-c efficacy (39); other studies have reiterated similar ideas (40).

SMAC, a proapoptotic molecule released from mitochondria, plays an obligatory role in driving apoptosis and suppressing proliferation in human leukemia (41, 42). One function of SMAC is to quell the caspase inhibitory properties of the IAP proteins XIAP and survivin, for example. Survivin is highly expressed in AML, and expression predicts poor clinical outcomes (43). XIAP expression is associated with monocytic differentiation in adult de novo AML and may as well be of prognostic significance for overall survival (44). Our results show that the C6-ceramide-tamoxifen regimen promoted in tandem the release of SMAC from mitochondria and the downregulation of survivin and XIAP, and thus these agents efficiently target obligatory apoptosis-inhibitory machinery in AML. Similarly, Paschall et al (45) have shown that ceramide targets XIAP to sensitize cancer cells to apoptosis.

Nanoliposomal C6-ceramide has been investigated as a single agent and in combinatorial therapies (46), and recent work discusses preclinical development of C6-ceramide nanoliposomes (47). Of note, alterations in sphingolipid metabolism may play a crucial role in the regulation of cancer glycolytic capacity (48). In particular, C6-ceramide nanoliposomes have been shown to inhibit the glycolytic pathway in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (49), findings in line with results herein in AML. Our work shows that C6-ceramide-tamoxifen composite nanoliposomes were dose-wise equal to or more effective in inducing apoptosis, suppressing glycolytic capacity, and inhibiting mitochondrial complex I respiration, compared with the combination regimens, demonstrating the utility of combinatorial C6-ceramide-tamoxifen-containing nanotherapeutics as a potential new strategy in treating drug-resistant AML. Similar nanotherapies have been explored in multidrug-resistant ovarian cancer using ceramide and paclitaxel polymeric nanoparticles and tamoxifen-loaded biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles (50).

Tamoxifen is a potent inhibitor of ceramide glycosylation (13). This allied activity has advantages because ceramide can be glycosylated and thereby “inactivated,” a reaction that is associated with ceramide resistance and with multidrug resistance in leukemia (51), a daunting challenge to successful treatment (52, 53). In addition, Itoh et al (54) have shown that ceramide glycosylation contributes to chemotherapy resistance in leukemia, and Watters et al (55) have shown that targeting glycosylation by introduction of a GC synthase inhibitor synergizes with C6-ceramide nanoliposomes to induce apoptosis in natural killer cell leukemia. These works strongly support the utility of targeting ceramide metabolism to enhance therapeutic outcome, and our MS results readily demonstrate the efficiency of tamoxifen as a regulator of ceramide glycosylation.

Short-chain ceramides can be metabolized to long-chain ceramides by hydrolysis via the salvage pathway (56, 57), a process observed in our study. Therefore, the contribution of C6-ceramide-derived long-chain ceramides to cytotoxic response merits investigation. We primarily generated C16:0 and C24:1 ceramides, molecular species that have been linked to apoptosis and membrane channel formation (58, 59). In addition, increases in long-chain ceramides have also been linked to autophagy (60), and in preliminary work, we have observed that the C6-ceramide-tamoxifen regimen increases expression of the autophagy marker LC3II in AML cells (unpublished observations). These interesting issues are currently being examined.

This work demonstrates that a ceramide-containing drug combination consisting of C6-ceramide and tamoxifen (or DMT) is synergistic in promoting cell death in AML cells via downstream targets that include mitochondria (mitochondrial membrane potential, complex I respiration, complex V ATP synthesis, cytochrome c, SMAC), glycolysis, and IAPs. The mechanism of cell death is ROS dependent, as introduction of antioxidant reversed cytotoxicity. Interestingly, although mechanism of action was not investigated, we have previously demonstrated that tamoxifen enhances the cytotoxic response to C6-ceramide in breast cancer and in colon cancer cells (18, 61), suggesting that this ceramide-centric combination has broad application in cancer. We propose that the basis of cooperative action between C6-ceramide and tamoxifen is in part related to tamoxifen inhibition of C6-ceramide and long-chain ceramide glycosylation, thus potentiating the ceramide tumor-suppressor effect.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- AML

- acute myelogenous leukemia

- DMT

- N-desmethyltamoxifen

- GC

- glucosylceramide

- IAP

- inhibitors of apoptosis protein

- PBMC

- peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PI

- propidium iodide

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- S1-P

- sphingosine 1-phosphate

- SMAC

- second mitochondria-derived activator of caspase

This work was supported by a grant from the Office of Extramural Research, National Institutes of Health (P01-CA171983).

REFERENCES

- 1.Zheng W., Kollmeyer J., Symolon H., Momin A., Munter E., Wang E., Kelly S., Allegood J. C., Liu Y., Peng Q., et al. 2006. Ceramides and other bioactive sphingolipid backbones in health and disease: lipidomic analysis, metabolism and roles in membrane structure, dynamics, signaling and autophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1758: 1864–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gangoiti P., Camacho L., Arana L., Ouro A., Granado M. H., Brizuela L., Casas J., Fabrias G., Abad J. L., Delgado A., et al. 2010. Control of metabolism and signaling of simple bioactive sphingolipids: implications in disease. Prog. Lipid Res. 49: 316–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delgado A., Fabrias G., Bedia C., Casas J., and Abad J. L.. 2012. Sphingolipid modulation: a strategy for cancer therapy. Anticancer. Agents Med. Chem. 12: 285–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morales A., Lee H., Goni F. M., Kolesnick R., and Fernandez-Checa J. C.. 2007. Sphingolipids and cell death. Apoptosis. 12: 923–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morad S. A., and Cabot M. C.. 2013. Ceramide-orchestrated signalling in cancer cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 13: 51–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barth B. M., Cabot M. C., and Kester M.. 2011. Ceramide-based therapeutics for the treatment of cancer. Anticancer. Agents Med. Chem. 11: 911–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Truman J. P., Garcia-Barros M., Obeid L. M., and Hannun Y. A.. 2014. Evolving concepts in cancer therapy through targeting sphingolipid metabolism. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1841: 1174–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Y. Y., Han T. Y., Giuliano A. E., and Cabot M. C.. 1999. Expression of glucosylceramide synthase, converting ceramide to glucosylceramide, confers adriamycin resistance in human breast cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 1140–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y. Y., Han T. Y., Giuliano A. E., Hansen N., and Cabot M. C.. 2000. Uncoupling ceramide glycosylation by transfection of glucosylceramide synthase antisense reverses adriamycin resistance. J. Biol. Chem. 275: 7138–7143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Y. Y., Han T. Y., Giuliano A. E., and Cabot M. C.. 2001. Ceramide glycosylation potentiates cellular multidrug resistance. FASEB J. 15: 719–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Payne S. G., Milstien S., and Spiegel S.. 2002. Sphingosine-1-phosphate: dual messenger functions. FEBS Lett. 531: 54–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pyne N. J., McNaughton M., Boomkamp S., MacRitchie N., Evangelisti C., Martelli A. M., Jiang H. R., Ubhi S., and Pyne S.. 2016. Role of sphingosine 1-phosphate receptors, sphingosine kinases and sphingosine in cancer and inflammation. Adv. Biol. Regul. 60: 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cabot M. C., Giuliano A. E., Volner A., and Han T. Y.. 1996. Tamoxifen retards glycosphingolipid metabolism in human cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 394: 129–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morad S. A., Levin J. C., Tan S. F., Fox T. E., Feith D. J., and Cabot M. C.. 2013. Novel off-target effect of tamoxifen—inhibition of acid ceramidase activity in cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1831: 1657–1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morad S. A., Tan S. F., Feith D. J., Kester M., Claxton D. F., Loughran T. P. Jr., Barth B. M., Fox T. E., and Cabot M. C.. 2015. Modification of sphingolipid metabolism by tamoxifen and N-desmethyltamoxifen in acute myelogenous leukemia—impact on enzyme activity and response to cytotoxics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1851: 919–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maurer B. J., Metelitsa L. S., Seeger R. C., Cabot M. C., and Reynolds C. P.. 1999. Increase of ceramide and induction of mixed apoptosis/necrosis by N-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-retinamide in neuroblastoma cell lines. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 91: 1138–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tran M. A., Smith C. D., Kester M., and Robertson G. P.. 2008. Combining nanoliposomal ceramide with sorafenib synergistically inhibits melanoma and breast cancer cell survival to decrease tumor development. Clin. Cancer Res. 14: 3571–3581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morad S. A., Levin J. C., Shanmugavelandy S. S., Kester M., Fabrias G., Bedia C., and Cabot M. C.. 2012. Ceramide–antiestrogen nanoliposomal combinations—novel impact of hormonal therapy in hormone-insensitive breast cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 11: 2352–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brault J. J., Pizzimenti N. M., Dentel J. N., and Wiseman R. W.. 2013. Selective inhibition of ATPase activity during contraction alters the activation of p38 MAP kinase isoforms in skeletal muscle. J. Cell. Biochem. 114: 1445–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeczycki T. N., Menefee A. L., Jitrapakdee S., Wallace J. C., Attwood P. V., Maurice M. St., and Cleland W. W.. 2011. Activation and inhibition of pyruvate carboxylase from Rhizobium etli. Biochemistry. 50: 9694–9707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Christensen M. E., Jansen E. S., Sanchez W., and Waterhouse N. J.. 2013. Flow cytometry based assays for the measurement of apoptosis-associated mitochondrial membrane depolarisation and cytochrome c release. Methods. 61: 138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng H., Smith D. J., and Nagley P.. 2012. Application of flow cytometry to determine differential redistribution of cytochrome c and Smac/DIABLO from mitochondria during cell death signaling. PLoS One. 7: e42298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fox T. E., Bewley M. C., Unrath K. A., Pedersen M. M., Anderson R. E., Jung D. Y., Jefferson L. S., Kim J. K., Bronson S. K., Flanagan J. M., et al. 2011. Circulating sphingolipid biomarkers in models of type 1 diabetes. J. Lipid Res. 52: 509–517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fabian C., Tilzer L., and Sternson L.. 1981. Comparative binding affinities of tamoxifen, 4-hydroxytamoxifen, and desmethyltamoxifen for estrogen receptors isolated from human breast carcinoma: correlation with blood levels in patients with metastatic breast cancer. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 2: 381–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wenner C. E. 2012. Targeting mitochondria as a therapeutic target in cancer. J. Cell. Physiol. 227: 450–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zigdon H., Kogot-Levin A., Park J. W., Goldschmidt R., Kelly S., Merrill A. H. Jr., Scherz A., Pewzner-Jung Y., Saada A., and Futerman A. H.. 2013. Ablation of ceramide synthase 2 causes chronic oxidative stress due to disruption of the mitochondrial respiratory chain. J. Biol. Chem. 288: 4947–4956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Radad K., Rausch W. D., and Gille G.. 2006. Rotenone induces cell death in primary dopaminergic culture by increasing ROS production and inhibiting mitochondrial respiration. Neurochem. Int. 49: 379–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morad S. A., and Cabot M. C.. 2015. Tamoxifen regulation of sphingolipid metabolism—therapeutic implications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1851: 1134–1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Delgado A., Casas J., Llebaria A., Abad J. L., and Fabrias G.. 2006. Inhibitors of sphingolipid metabolism enzymes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1758: 1957–1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Day S. J., Boasberg P. D., Kristedja T. S., Martin M., Wang H. J., Fournier P., Cabot M., DeGregorio M. W., and Gammon G.. 2001. High-dose tamoxifen added to concurrent biochemotherapy with decrescendo interleukin-2 in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer. 92: 609–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreira P. I., Custodio J., Moreno A., Oliveira C. R., and Santos M. S.. 2006. Tamoxifen and estradiol interact with the flavin mononucleotide site of complex I leading to mitochondrial failure. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 10143–10152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colombini M. Ceramide channels and mitochondrial outer membrane permeability. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. Epub ahead of print. January 22, 2016; doi:10.1007/s10863-016-9646-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chang K. T., Anishkin A., Patwardhan G. A., Beverly L. J., Siskind L. J., and Colombini M.. 2015. Ceramide channels: destabilization by Bcl-xL and role in apoptosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1848: 2374–2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Glover C. J., Rabow A. A., Isgor Y. G., Shoemaker R. H., and Covell D. G.. 2007. Data mining of NCI’s anticancer screening database reveals mitochondrial complex I inhibitors cytotoxic to leukemia cell lines. Biochem. Pharmacol. 73: 331–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koopman W. J., Verkaart S., Visch H. J., van der Westhuizen F. H., Murphy M. P., van den Heuvel L. W., Smeitink J. A., and Willems P. H.. 2005. Inhibition of complex I of the electron transport chain causes O2-. -mediated mitochondrial outgrowth. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 288: C1440–C1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bradbury D. A., Simmons T. D., Slater K. J., and Crouch S. P.. 2000. Measurement of the ADP:ATP ratio in human leukaemic cell lines can be used as an indicator of cell viability, necrosis and apoptosis. J. Immunol. Methods. 240: 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gudz T. I., Tserng K. Y., and Hoppel C. L.. 1997. Direct inhibition of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex III by cell-permeable ceramide. J. Biol. Chem. 272: 24154–24158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Di Paola M., Cocco T., and Lorusso M.. 2000. Ceramide interaction with the respiratory chain of heart mitochondria. Biochemistry. 39: 6660–6668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen W. L., Wang J. H., Zhao A. H., Xu X., Wang Y. H., Chen T. L., Li J. M., Mi J. Q., Zhu Y. M., Liu Y. F., et al. 2014. A distinct glucose metabolism signature of acute myeloid leukemia with prognostic value. Blood. 124: 1645–1654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xu R. H., Pelicano H., Zhou Y., Carew J. S., Feng L., Bhalla K. N., Keating M. J., and Huang P.. 2005. Inhibition of glycolysis in cancer cells: a novel strategy to overcome drug resistance associated with mitochondrial respiratory defect and hypoxia. Cancer Res. 65: 613–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rajalingam K., Oswald M., Gottschalk K., and Rudel T.. 2007. Smac/DIABLO is required for effector caspase activation during apoptosis in human cells. Apoptosis. 12: 1503–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jia L., Patwari Y., Kelsey S. M., Srinivasula S. M., Agrawal S. G., Alnemri E. S., and Newland A. C.. 2003. Role of Smac in human leukaemic cell apoptosis and proliferation. Oncogene. 22: 1589–1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carter B. Z., Qiu Y., Huang X., Diao L., Zhang N., Coombes K. R., Mak D. H., Konopleva M., Cortes J., Kantarjian H. M., et al. 2012. Survivin is highly expressed in CD34(+)38(-) leukemic stem/progenitor cells and predicts poor clinical outcomes in AML. Blood. 120: 173–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tamm I., Richter S., Scholz F., Schmelz K., Oltersdorf D., Karawajew L., Schoch C., Haferlach T., Ludwig W. D., and Wuchter C.. 2004. XIAP expression correlates with monocytic differentiation in adult de novo AML: impact on prognosis. Hematol. J. 5: 489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Paschall A. V., Zimmerman M. A., Torres C. M., Yang D., Chen M. R., Li X., Bieberich E., Bai A., Bielawski J., Bielawska A., et al. 2014. Ceramide targets xIAP and cIAP1 to sensitize metastatic colon and breast cancer cells to apoptosis induction to suppress tumor progression. BMC Cancer. 14: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang Y., DiVittore N. A., Kaiser J. M., Shanmugavelandy S. S., Fritz J. L., Heakal Y., Tagaram H. R., Cheng H., Cabot M. C., Staveley-O’Carroll K. F., et al. 2011. Combinatorial therapies improve the therapeutic efficacy of nanoliposomal ceramide for pancreatic cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 12: 574–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kester M., Bassler J., Fox T. E., Carter C. J., Davidson J. A., and Parette M. R.. 2015. Preclinical development of a C6-ceramide NanoLiposome, a novel sphingolipid therapeutic. Biol. Chem. 396: 737–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watson D. G., Tonelli F., Alossaimi M., Williamson L., Chan E., Gorshkova I., Berdyshev E., Bittman R., Pyne N. J., and Pyne S.. 2013. The roles of sphingosine kinases 1 and 2 in regulating the Warburg effect in prostate cancer cells. Cell. Signal. 25: 1011–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ryland L. K., Doshi U. A., Shanmugavelandy S. S., Fox T. E., Aliaga C., Broeg K., Baab K. T., Young M., Khan O., Haakenson J. K., et al. 2013. C6-ceramide nanoliposomes target the Warburg effect in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. PLoS One. 8: e84648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Devalapally H., Duan Z., Seiden M. V., and Amiji M. M.. 2008. Modulation of drug resistance in ovarian adenocarcinoma by enhancing intracellular ceramide using tamoxifen-loaded biodegradable polymeric nanoparticles. Clin. Cancer Res. 14: 3193–3203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xie P., Shen Y. F., Shi Y. P., Ge S. M., Gu Z. H., Wang J., Mu H. J., Zhang B., Qiao W. Z., and Xie K. M.. 2008. Overexpression of glucosylceramide synthase in associated with multidrug resistance of leukemia cells. Leuk. Res. 32: 475–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shaffer B. C., Gillet J. P., Patel C., Baer M. R., Bates S. E., and Gottesman M. M.. 2012. Drug resistance: still a daunting challenge to the successful treatment of AML. Drug Resist. Updat. 15: 62–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sakamoto K. M., Grant S., Saleiro D., Crispino J. D., Hijiya N., Giles F., Platanias L., and Eklund E. A.. 2015. Targeting novel signaling pathways for resistant acute myeloid leukemia. Mol. Genet. Metab. 114: 397–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Itoh M., Kitano T., Watanabe M., Kondo T., Yabu T., Taguchi Y., Iwai K., Tashima M., Uchiyama T., and Okazaki T.. 2003. Possible role of ceramide as an indicator of chemoresistance: decrease of the ceramide content via activation of glucosylceramide synthase and sphingomyelin synthase in chemoresistant leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. 9: 415–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watters R. J., Fox T. E., Tan S. F., Shanmugavelandy S., Choby J. E., Broeg K., Liao J., Kester M., Cabot M. C., Loughran T. P., et al. 2013. Targeting glucosylceramide synthase synergizes with C6-ceramide nanoliposomes to induce apoptosis in natural killer cell leukemia. Leuk. Lymphoma. 54: 1288–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chapman J. V., Gouaze-Andersson V., Messner M. C., Flowers M., Karimi R., Kester M., Barth B. M., Liu X., Liu Y. Y., Giuliano A. E., et al. 2010. Metabolism of short-chain ceramide by human cancer cells—implications for therapeutic approaches. Biochem. Pharmacol. 80: 308–315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ogretmen B., Pettus B. J., Rossi M. J., Wood R., Usta J., Szulc Z., Bielawska A., Obeid L. M., and Hannun Y. A.. 2002. Biochemical mechanisms of the generation of endogenous long chain ceramide in response to exogenous short chain ceramide in the A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Role for endogenous ceramide in mediating the action of exogenous ceramide. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 12960–12969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Siskind L. J., Kolesnick R. N., and Colombini M.. 2002. Ceramide channels increase the permeability of the mitochondrial outer membrane to small proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 26796–26803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pinto S. N., Silva L. C., Futerman A. H., and Prieto M.. 2011. Effect of ceramide structure on membrane biophysical properties: the role of acyl chain length and unsaturation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1808: 2753–2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pattingre S., Bauvy C., Levade T., Levine B., and Codogno P.. 2009. Ceramide-induced autophagy: to junk or to protect cells? Autophagy. 5: 558–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Morad S. A., Madigan J. P., Levin J. C., Abdelmageed N., Karimi R., Rosenberg D. W., Kester M., Shanmugavelandy S. S., and Cabot M. C.. 2013. Tamoxifen magnifies therapeutic impact of ceramide in human colorectal cancer cells independent of p53. Biochem. Pharmacol. 85: 1057–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]