Abstract

UbiA prenyltransferase domain-containing protein-1 (UBIAD1) utilizes geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGpp) to synthesize the vitamin K2 subtype menaquinone-4. Previously, we found that sterols trigger binding of UBIAD1 to endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-localized HMG-CoA reductase, the rate-limiting enzyme in synthesis of cholesterol and nonsterol isoprenoids, including GGpp. This binding inhibits sterol-accelerated degradation of reductase, which contributes to feedback regulation of the enzyme. The addition to cells of geranylgeraniol (GGOH), which can become converted to GGpp, triggers release of UBIAD1 from reductase, allowing for its maximal degradation and permitting ER-to-Golgi transport of UBIAD1. Here, we further characterize geranylgeranyl-regulated transport of UBIAD1. Results of this characterization support a model in which UBIAD1 continuously cycles between the ER and medial-trans Golgi of isoprenoid-replete cells. Upon sensing a decline of GGpp in ER membranes, UBIAD1 becomes trapped in the organelle where it inhibits reductase degradation. Mutant forms of UBIAD1 associated with Schnyder corneal dystrophy (SCD), a human eye disease characterized by corneal accumulation of cholesterol, are sequestered in the ER and block reductase degradation. Collectively, these findings disclose a novel sensing mechanism that allows for stringent metabolic control of intracellular trafficking of UBIAD1, which directly modulates reductase degradation and becomes disrupted in SCD.

Keywords: endoplasmic reticulum, lipid metabolism, isoprenoid, protein trafficking, vitamin K, UbiA prenyltransferase domain-containing protein-1

UbiA prenyltransferase domain-containing protein-1 (UBIAD1) belongs to the UbiA superfamily of integral membrane prenyltransferases (1). These enzymes contain 8–10 transmembrane helices and catalyze transfer of isoprenyl groups to aromatic acceptors, producing a wide range of molecules such as ubiquinones, hemes, chlorophylls, vitamin E, and vitamin K. In animals, UBIAD1 catalyzes transfer of the 20-carbon geranylgeranyl moiety from geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGpp) to menadione released from plant-derived phylloquinone, thereby generating the vitamin K2 subtype, menaquinone-4 (MK-4) (2, 3).

Mutations in the UBIAD1 gene are associated with Schnyder corneal dystrophy (SCD), an autosomal dominant human eye disease characterized by progressive opacification of the cornea, owing to abnormal accumulation of cholesterol and other lipids (4, 5). Systemic dyslipidemia appears to be associated with some, but not all, SCD cases (6, 7). Missense mutations that alter 20 amino acid residues in UBIAD1 have been identified in ∼50 SCD families (8, 9). Several of these altered amino acids reside within the active site of UBIAD1 (10, 11). A link between UBIAD1 and cholesterol metabolism was first provided by coimmunoprecipitation studies that showed an association of UBIAD1 with the cholesterol biosynthetic enzyme, HMG-CoA reductase (8). More recently, we showed that UBIAD1 inhibits sterol-accelerated endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation (ERAD) of reductase (12), one of several feedback mechanisms that converge on the enzyme to maintain cholesterol homeostasis (13).

The polytopic, ER-localized HMG-CoA reductase catalyzes reduction of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, a rate-limiting step in synthesis of cholesterol as well as nonsterol isoprenoids including farnesyl pyrophosphate (Fpp) and GGpp that are transferred to many cellular proteins and utilized in synthesis of ubiquinone, MK-4, heme, and dolichol (2, 13, 14). Intracellular accumulation of sterols causes reductase to bind ER membrane proteins called Insigs (15, 16), which leads to ubiquitination of the enzyme by Insig-associated ubiquitin ligases (16–19). Ubiquitinated reductase is then extracted across ER membranes and released into the cytosol for degradation by 26S proteasomes (20, 21). Maximal degradation requires the addition to cells of geranylgeraniol (GGOH), the alcohol derivative of GGpp (16). We postulate that GGOH becomes converted to GGpp, which augments reductase ERAD by enhancing its membrane extraction (21). Recently, we found that sterols also cause reductase to bind to UBIAD1 (12). GGpp triggers release of UBIAD1 from reductase, allowing for its maximal ERAD. Importantly, the addition to cells of farnesol, the alcohol derivative of Fpp, neither inhibits the binding of UBIAD1 to reductase nor augments ERAD of reductase (12, 16). Two of the 20 SCD-associated mutants of UBIAD1 (N102S and G177R) resisted GGpp-induced displacement from reductase and thereby blocked its degradation (12).

In the course of our studies, we discovered that GGpp also stimulates translocation of UBIAD1 from the ER to the Golgi (12). SCD-associated UBIAD1 (N102S) and (G177R) are refractory to this GGpp-induced Golgi transport and localize to the ER. Building on these observations, we show in the current study that UBIAD1 localizes to the medial-trans cisternae of the Golgi in isoprenoid-replete cells. All 20 of the SCD-associated mutants of UBIAD1 are defective in Golgi transport and remain sequestered in the ER where they inhibit reductase ERAD in a seemingly dominant-negative fashion. Intriguingly, acute depletion of isoprenoids triggers rapid retrograde transport of UBIAD1 from the Golgi to the ER. Although UBIAD1 localizes to the Golgi of isoprenoid-replete cells in the steady state, the protein accumulates in the ER when transport from the organelle is blocked. These findings suggest a model in which UBIAD1 constitutively cycles between the Golgi and ER. Upon sensing GGpp depletion in membranes of the ER, UBIAD1 becomes trapped in the organelle and inhibits reductase ERAD so as to stimulate mevalonate synthesis for replenishment of GGpp. This novel sensing mechanism directly controls ERAD of reductase and becomes disrupted in SCD, which likely contributes to the accumulation of cholesterol that characterizes the eye disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

We obtained GGOH, GGpp, Fpp, nocodazole, and brefeldin A (BFA) from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX); cycloheximide was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA); 25-hydroxycholesterol and cholesterol was obtained from Steraloids (Newport, RI); hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin was obtained from (Cyclodextrin Technologies Development, Alachua, FL). Recombinant His-tagged Sar1DN was expressed in Escherichia coli and isolated on Ni-NTA agarose (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) as previously described (22). The buffer was exchanged by dialysis against 25 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.2), 125 mM potassium acetate, 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM glutathione, 10 μM guanosine diphosphate, and 50 μM EGTA. SR-12813 was synthesized by the Core Medicinal Chemistry laboratory at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center or obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Other reagents, including newborn calf lipoprotein-deficient serum (LPDS, d > 1.215 g/ml), sodium compactin, and sodium mevalonate, were prepared or obtained as previously described (20, 23).

Expression plasmids

The expression plasmids, pCMV-Myc-UBIAD1, which encodes human UBIAD1 containing a single copy of a Myc epitope at the N-terminus under transcriptional control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter, pCMV-Myc-UBIAD1 (N102S) encoding Myc-tagged human UBIAD1 harboring the SCD-associated asparagine-102 to serine (N102S) mutation, and pCMV-Myc-UBIAD1 (G177R) encoding Myc-tagged human UIBAD1 harboring the SCD-associated glycine-177 to arginine mutation were previously described (12). The remaining SCD-associated mutants of UBIAD1 were generated using the QuikChange® site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and pCMV-Myc-UBIAD1 as a template. The expression plasmid, pDsRed-Golgi, encoding a fusion protein consisting of DsRed-Monomer and the N-terminal 81 amino acids of human β1,4-galactosyltransferase was obtained from Clontech.

Cell culture

SV-589 cells are a line of immortalized human fibroblasts expressing the SV40 large T-antigen (24). Monolayers of SV-589 cells were maintained in medium A (DMEM containing 1,000 mg/l glucose, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FCS at 37°C, 5% CO2. SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells, a line of SV-589 cells that stably express Myc-UBIAD1, were generated by transfection of SV-589 cells with 3 μg pCMV-Myc-UBIAD1 using FuGENE6 transfection reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) as described below, followed by 2 weeks of selection in medium A supplemented with 10% FCS and 700 μg/ml G418. Individual colonies were isolated using cloning cylinders. Clonal isolates from expanded colonies were obtained using serial dilution in 96-well plates. Clones were evaluated by immunofluorescence microscopy using IgG-9E10 against the Myc epitope (described below).

CHO-K1/pMyc-UBIAD1 and UT-2/pMyc-UBIAD1, lines of CHO-K1 and reductase-deficient UT-2 cells (25) that stably express Myc-UBIAD1, were generated by transfection of cells with 3 μg pCMV-Myc-UBIAD1 as described below, followed by 2 weeks of selection in medium B (1:1 mixture of Ham’s F-12 medium and DMEM containing 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate) containing 5% FCS and 700 μg/ml G418. The medium for UT-2 cells was further supplemented with 200 μM mevalonate. Individual colonies were isolated using cloning cylinders, and expression of Myc-UBIAD1 was determined by immunoblot analysis. Select colonies were expanded and then further purified by serial dilution in 96-well plates. Individual clones were screened by immunofluorescence using IgG-9E10 as described below. CHO-K1/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells were maintained in monolayer in medium B containing 5% FCS and 700 μg/ml G418 at 37°C, 8% CO2. Monolayers of UT-2/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells were grown at 37°C, 8% CO2 in identical medium supplemented with 200 μM mevalonate.

CHO-7 cells, a subline of CHO-K1 cells selected for growth in LPDS (26), were grown in monolayer at 37°C, 8% CO2. The cells were maintained in medium B supplemented with 5% LPDS. Monolayers of SRD-13A/pGFP-Scap, a line of Scap-deficient CHO-7 cells that stably express GFP-Scap (27), were maintained at 37°C, 8% CO2 in medium B supplemented with 5% LPDS.

Transfection and immunofluorescence

Transient transfection of cells with FuGENE6 transfection reagent was carried out as previously described (12, 15). Conditions of subsequent incubations are described in the figure legends. Following incubations, cells were washed with PBS and subsequently fixed and permeabilized for 15 min in methanol at −20°C. Upon blocking with 1 mg/ml BSA in PBS, coverslips were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with primary antibodies [IgG-H8, a mouse monoclonal antibody against human UBIAD1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit polyclonal anti-GM130 IgG (28), IgG-9E10, a mouse monoclonal antibody against c-Myc purified from the culture medium of hybridoma clone 9E10 (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), and rabbit polyclonal anti-TGN46 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA)] diluted in PBS containing 1 mg/ml BSA. Bound antibodies were visualized with goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 or Alexa Fluor 594 and goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 594 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) as described in the figure legends. Coverslips were also stained for 5 min with 300 nM 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Life Technologies) to visualize nuclei. The coverslips were then mounted in Mowiol 4-88 solution (Calbiochem/EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) or Fluoromount G (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA). Fluorescence imaging was performed using a DeltaVision microscopy imaging system (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA) equipped with a CoolSNAP HQ2 camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) and objective oil lenses 60×/1.42 and 100×/1.40 (Olympus, Waltham, MA) as indicated in figure legends. The z stacks were deconvolved and Pearson correlation coefficients for each z stack were generated using DeltaVision SoftWoRx software (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA). Additional fluorescence imaging was performed using a Zeiss Axio Observer Epifluorescence microscope using a 63×/1.4 oil plan-apochromat objective and Zeiss Axiocam color digital camera (Zeiss, Peabody, MA) in black and white mode as indicated in the figure legends. Brightness levels were adjusted across the entire images using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Preparation of cytosol

Rat liver cytosol was prepared from adult male Sprague-Dawley rats as previously described (29). Cytosol from isoprenoid-depleted UT-2 cells was prepared as follows. UT-2 cells were set up on day 0 at 3 × 105 cells per 100 mm dish in medium B containing 5% FCS and 200 μM mevalonate. On day 3, cells were depleted of isoprenoids though incubation in medium B supplemented with 5% FCS in the absence of mevalonate. After 16 h at 37°C, cells were harvested into the medium by scraping and collected by centrifugation, after which cell pellets were washed with PBS supplemented with a protease inhibitor cocktail consisting of 20 μM leupeptin, 5 μg/ml pepstatin A, 2 μg/ml aprotinin, 25 μg/ml N-acetyl-leucinal-leucinal-norleucinal, and 1 mM dithiotheitol. The washed cells from 250 dishes were resuspended in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.2), 250 mM sorbitol, 70 mM potassium acetate, 5 mM potassium EGTA, and 2.5 mM magnesium acetate supplemented with protease inhibitors. The resuspended cells were then lysed by passage through an 18 gauge needle 30 times, followed by 25 strokes in a 50 ml Dounce homogenizer fitted with a Teflon pestle. The resulting homogenates were subjected to centrifugation at 1,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant of this spin was then subjected to centrifugation at 100,000 g for 1 h at 4°C. The final supernatant, designated as cytosol (∼2 mg/ml), was divided into multiple aliquots, snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C. For experiments, tubes were thawed in a 37°C water bath and placed on ice until use.

In vitro vesicle-formation assay

SV-589 cells were set up for experiments as described in the figure legends. Following incubations described in figure legends, cells were harvested into medium by scraping and pooled suspensions from triplicate dishes were subjected to centrifugation at 1,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. Cell pellets were resuspended in 0.5 ml buffer containing 10 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.2), 250 mM sorbitol, 10 mM potassium acetate, 1.5 mM magnesium acetate, and protease inhibitors, passed through a 22 gauge needle 30 times, and centrifuged at 1,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatants were transferred to siliconized microfuge tubes and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 3 min at 4°C. Each pellet was suspended in 50 μl of buffer containing 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.2), 250 mM sorbitol, 70 mM potassium acetate, 5 mM potassium EGTA, 2.5 mM magnesium acetate, and protease inhibitors to obtain microsomes that were pooled and used in the in vitro vesicle-formation assay described below. The protein concentration of an aliquot (5 μl) of microsomal suspensions was determined using PierceTM Coomassie Plus protein assay reagent (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using BSA as standard.

The protocol used in this study was adapted from previously described procedures (27, 30, 31). In a final volume of 100 μl, each reaction contained 50 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.2), 250 mM sorbitol, 70 mM potassium acetate, 5 mM potassium EGTA, 2.5 mM magnesium acetate, 1.5 mM ATP, 0.5 mM GTP, 10 mM creatine phosphate, 4 units/ml of creatine kinase, protease inhibitors, 80–100 μg protein of SV-589 microsomes, and 10–100 μg rat liver or UT-2 cytosol. Incubations were carried out in siliconized 1.5 ml microfuge tubes for 20 min at 37°C (unless otherwise indicated). Reactions were terminated by transfer of tubes to ice, followed by centrifugation at 16,000 g for 3 min at 4°C to obtain a medium-speed pellet (P16) and a medium-speed supernatant (S16). The S16 fraction was then subjected to an additional round of centrifugation at 100,000 g for 30 min at 4°C to obtain a high-speed pellet (P100). The P16 and P100 were resuspended in buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.6), 100 mM NaCl, and 1% (w/v) SDS plus protease inhibitors supplemented with 4× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and heated at 95°C for 5 min. Aliquots of the P16 (7.5 μl) and P100 (30 μl) were subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE, transferred to nylon filters, and analyzed by immunoblotting. The P16 and P100 fractions are referred to membranes and vesicles, respectively. Primary antibodies used for immunoblot analysis include: IgG-H8 against human UBIAD1; IgG-4H4, a mouse monoclonal antibody against hamster Scap (32); and rabbit polyclonal anti-ribophorin I IgG (Abcam).

Microinjection of SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells

Microinjection was performed with a Transjector 5246 and a Micromanipulator 5171 (Eppendorf, Hauppauge, NY). SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells on glass coverslips were changed to medium A containing 50 mM HEPES/KOH (pH 7.4) and 10% FCS and injected into the cytoplasm with 1 mg/ml Sar1DN or 1 mg/ml BSA as a control together with 2 mg/ml lysine fixable 70 kDa Texas-Red conjugated dextran (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) as injection marker. Following incubation for 3 h at 37°C, the cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS for 15 min at room temperature and permeabilized for 10 min in methanol at −20°C. Upon blocking with 1 mg/ml BSA in PBS, the cells were labeled with the indicated monoclonal primary antibodies [IgG-9E10 against Myc or anti-GM130 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA)] followed by Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies. DNA was stained for 5 min with 1 μg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen) in PBS. Epifluorescence images were obtained using a Plan-Neofluar 40×/1.3 DIC objective (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), an Axiovert 200M microscope (Zeiss), an Orca 285 camera (Hamamatsu, Hamamatsu City, Japan), and the Openlab 4.0.2 software.

RESULTS

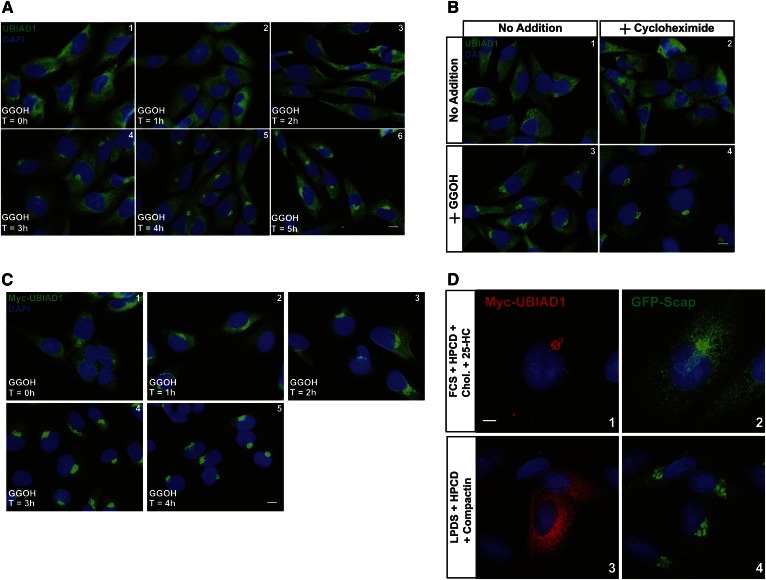

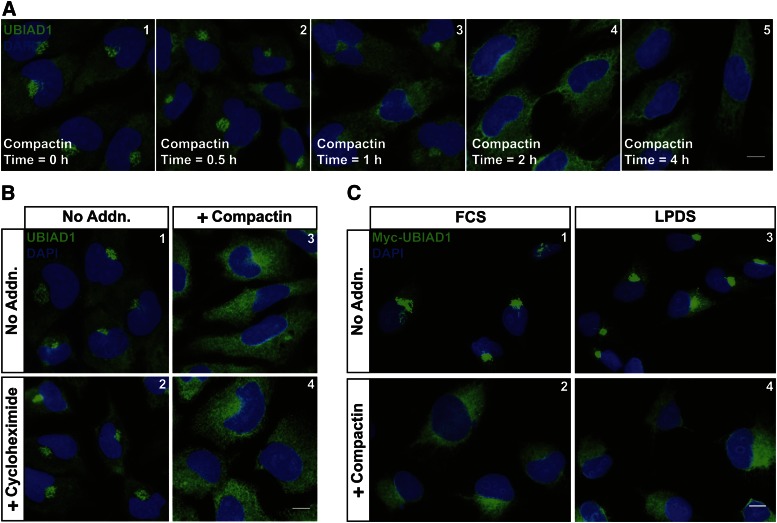

Figure 1A shows that endogenous UBIAD1 localized to ER membranes when SV-589 cells, a line of transformed human fibroblasts (24), were depleted of sterol and nonsterol isoprenoids through incubation for 16 h in medium containing LPDS and the reductase inhibitor, compactin (panel 1). The addition of GGOH to the cells stimulated translocation of UBIAD1 from the ER to the Golgi in a time-dependent manner (panels 2–6). GGOH-induced transport of UBIAD1 to the Golgi continued in the presence of the protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide (Fig. 1B). The nonsterol isoprenoid similarly stimulated ER-to-Golgi transport of Myc-UBIAD1 in SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells, which stably overexpress the protein (Fig. 1C). Figure 1D compares the subcellular localization of Myc-UBIAD1 with that of Scap, a membrane protein whose transport from the ER to the Golgi is regulated by sterols (27, 33). The results show that a majority of Myc-UBIAD1 localized to the Golgi of sterol-replete SRD-13A/pGFP-Scap cells (Fig. 1D, panel 1), Scap-deficient Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells that stably overexpress GFP-Scap (27). In contrast, a significant fraction of GFP-Scap was present in the ER of sterol-replete SRD-13A/pGFP-Scap cells (panel 2). When cells were depleted of isoprenoids, Myc-UBIAD1 was sequestered in the ER (panel 3), whereas GFP-Scap translocated to the Golgi (panel 4).

Fig. 1.

Kinetics of geranylgeranyl-induced transport of UBIAD1 from the ER to the Golgi. SV-589 (A, B) and SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 (C) cells were set up on day 0 at 8 × 104 cells per well of 6-well plates with glass coverslips in medium A containing 10% FCS. On day 1, cells were depleted of isoprenoids though incubation in medium A containing 10% LPDS, 10 μM sodium compactin, and 50 μM sodium mevalonate. After 16 h at 37°C, cells were refed medium A containing 10% LPDS, 10 μM compactin, and 30 μM GGOH. In (B), some of the cells also received 50 μM cycloheximide. Following incubation for the indicated period of time (A, C) or 4 h (B) at 37°C, cells were fixed and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy using IgG-H8 (against endogenous UBIAD1) and IgG-9E10 (against transfected Myc-UBIAD1) using a Zeiss Axio Observer Epifluorescence microscope as described in the Materials and Methods. Scale bar is 10 microns. D: CHO-7/pGFP-Scap cells were set up on day 0 at 1 × 105 cells per well of 6-well plates with glass coverslips in medium B supplemented with 5% LPDS. On day 1, cells were transfected with pCMV-Myc-UBIAD1 (1 μg per dish) as described in the Materials and Methods. Four hours after transfection, cells received a direct addition of medium B containing either 5% FCS (panels 1 and 2) or 5% LPDS (panels 3 and 4) (final concentrations). Following incubation for 16 h at 37°C, the dishes received medium B containing either 5% FCS, 1% hydroxypropyl β-cyclodextrin (HPCD), 10 μg/ml cholesterol, and 10 μg/ml 25-hydroxycholesterol (panels 1 and 2) or 5% LPDS, 1% HPCD, and 10 μM compactin (panels 3 and 4). After 6 h at 37°C, cells were fixed and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy using IgG-9E10 (against Myc-UBIAD1) using a DeltaVision imaging system as described in Materials and Methods. Scale bar is 5 microns.

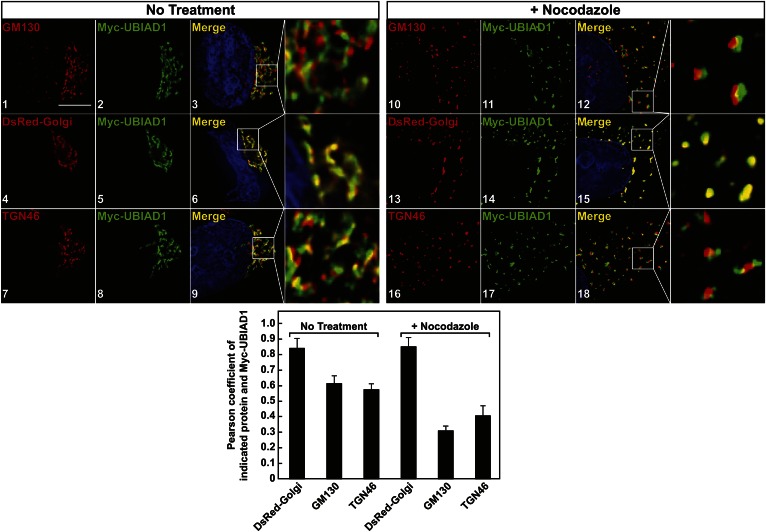

Deconvolution microscopy was next employed to analyze the subcellular localization of Myc-UBIAD1 in SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells. The results show that, as expected, Myc-UBIAD1 colocalized with mCherry-calnexin in ER membranes of SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells deprived of isoprenoids (supplementary Fig. 1A). When cells were cultured in sterol-replete FCS-containing medium, Myc-UBIAD1 colocalized with DsRed-Golgi (supplementary Fig. 1B), which consists of DsRed-Monomer fused to amino acids 1-81 of β1,4 galactosyltransferase that targets the fusion protein to the medial-trans cisternae of the Golgi (34). We further analyzed the colocalization of Myc-UBIAD1 with GM130 and TGN-46, which reside in the cis-Golgi and the trans-Golgi network (TGN), respectively (35, 36). In FCS-cultured cells, we observed an apparent overlap in localization of Myc-UBIAD1 with that of GM130 (Fig. 2, panels 1–3), DsRed-Golgi (panels 4–6), and TGN-46 (panels 7–9). The localization of UBIAD1 within the Golgi was further substantiated by conducting an experiment in cells subjected to treatment with the microtubule depolymerization agent, nocodazole. Treatment of cells with nocodazole is known to cause the Golgi ribbon to become fragmented into stacks that are dispersed throughout the cytoplasm (37). However, Golgi polarity is maintained in the presence of nocodazole, allowing visualization of individual stacks (38). When SV-589/Myc-UBIAD1 cells were treated with nocodazole, GM130, DsRed-Golgi, TGN-46, and Myc-UBIAD1 localized to scattered Golgi stacks in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2, panels 10–18). Colocalization of Myc-UBIAD1 with GM130 (panels 10–12) and TGN-46 (panels 16–18) was reduced in the presence of nocodazole; however, colocalization of the prenyltransferase with DsRed-Golgi remained unchanged compared with untreated controls (panels 13–15, see graph below images).

Fig. 2.

UBIAD1 localizes to medial-trans region of the Golgi apparatus as determined by deconvolution microscopy. SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells were set up on day 0 at 1.5 × 105 cells per 60 mm dish with glass coverslips in medium A containing 10% FCS. On day 1, cells were transfected with pDsRed-Golgi (3 μg per dish) as described in the Materials and Methods. Four hours after transfection, cells received a direct addition of medium A containing 10% FCS (final concentration). Following incubation for 16 h at 37°C, cells were treated for 2 h in the absence or presence of 5 μg/ml nocodazole. Cells were then fixed and analyzed by immunofluorescence deconvolution microscopy using IgG-9E10 (against transfected Myc-UBIAD1), anti-GM130, anti-TGN46, and a 100× oil objective as described in the Materials and Methods. Pearson correlation coefficients for the indicated protein and Myc-UBIAD1 are shown in graph below the images.

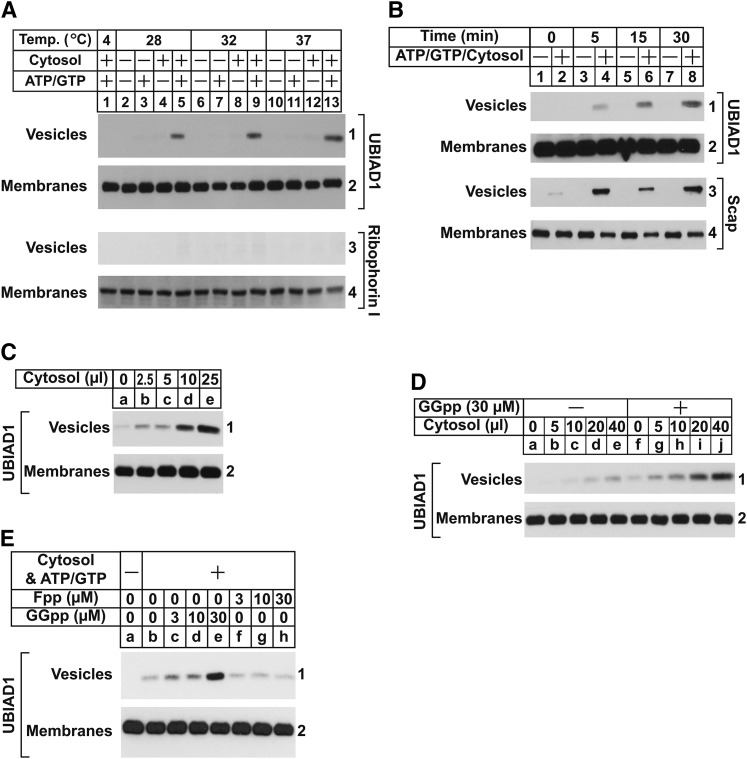

Anterograde transport of proteins from the ER to the Golgi occurs through their incorporation into transport vesicles that bud from ER membranes (39, 40). Methods that reconstitute in vitro formation of ER-derived transport vesicles have been established (30, 31). In these studies, membranes were incubated with nucleotide triphosphates (ATP/GTP) plus an ATP regenerating system and cytosol, which led to formation of vesicles that remained in the supernatant following centrifugation at 16,000 g, while donor membranes were pelleted. Using these methods, we next examined the in vitro budding of endogenous UBIAD1. In the experiment of Fig. 3A, cells were depleted of isoprenoids to sequester UBIAD1 in the ER. Membranes isolated from these isoprenoid-depleted cells were then incubated in the absence or presence of rat liver cytosol and ATP/GTP plus the ATP-regenerating system. Following incubation at various temperatures, donor membranes and vesicles were isolated by differential centrifugation and analyzed by immunoblot. UBIAD1 appeared in vesicles when reactions were carried out at 28, 32, or 37°C and supplemented with ATP/GTP and cytosol (Fig. 3A, panel 1, lanes 5, 9, and 13). ER-resident ribophorin I remained in donor membranes and was not visualized in vesicles (panel 3), indicating their generation did not result from nonspecific membrane fragmentation. The appearance of UBIAD1 was time-dependent (Fig. 3B, panel 1, lanes 4, 6, and 8); Scap also appeared in vesicles generated from complete reactions (panel 3, lanes 4, 6, and 8). Moreover, budding of UBIAD1 was proportional to the amount of cytosol used in the in vitro budding reaction (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

GGpp stimulates incorporation of UBIAD1 into vesicles in vitro. On day 0, SV-589 cells were set up at 2.5 × 105 cells per 100 mm dish in medium A containing 10% FCS. On day 3, cells were switched to medium A containing 10% LPDS, 10 μM compactin, and 50 μM mevalonate. Following incubation for 16 h at 37°C, cells were harvested for preparation of microsomes as described in the Materials and Methods. A–C: Aliquots of pooled microsomes were incubated at the indicated temperature (A) or 37°C (B, C) in the absence or presence of rat liver cytosol (0–25 μl per reaction), ATP, GTP, and an ATP-regenerating system as described in the Materials and Methods. Following incubation for 20 min (A, C) or the indicated period of time (B) at 37°C, reactions were centrifuged to separate vesicles and membranes that were subjected to SDS-PAGE, followed by immunoblot analysis with IgG-H8 (against UBIAD1), IgG-4H4 (against Scap), and anti-ribophorin I. D, E: Aliquots of pooled microsomes were incubated at 37°C with ATP, GTP, and an ATP-regenerating system in the absence or presence of cytosol (0–40 μl per reaction) prepared from reductase-deficient UT-2 cells and the indicated concentration of GGpp or Fpp. After 20 min at 37°C, membranes and vesicles were separated by centrifugation and analyzed by immunoblot with IgG-H8 (against UBIAD1).

Cytosol used in Fig. 3A–C was obtained from livers of rats that were not depleted of isoprenoids. Thus, we reasoned that residual GGpp in the cytosol stimulated incorporation of UBIAD1 into vesicles. Figure 3D reveals that addition of GGpp to cytosol obtained from isoprenoid-depleted reductase-deficient CHO-K1 cells [designated UT-2 (25)] enhanced incorporation of UBIAD1 into vesicles (panel 1, compare lanes a–e and f–j). Importantly, this enhancement was not observed in the presence of Fpp (Fig. 3E, panel 1, compare lanes c–e and f–h).

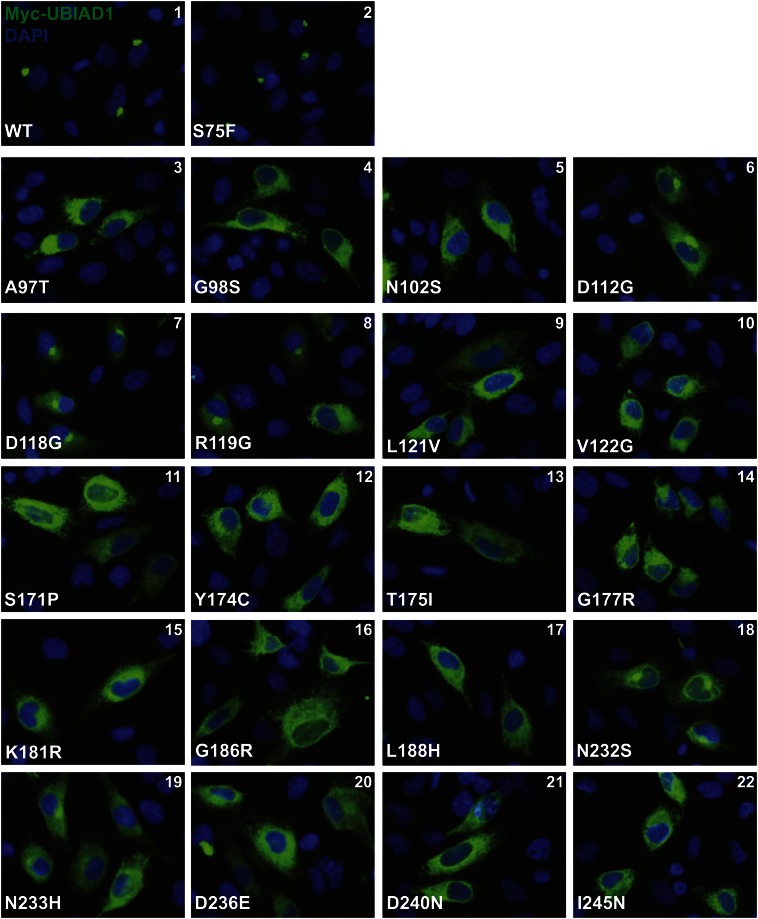

Twenty-four mutations that alter twenty amino acid residues in UBIAD1 protein have been identified in SCD families (8, 9). Asparagine-102 (N102) and glycine-177 (G177) are the most frequently altered UBIAD1 residues in SCD. We previously found that these SCD-associated mutants remain sequestered in the ER of isoprenoid-replete cells (12). Figure 4 shows an experiment that compares the subcellular localization of wild-type UBIAD1 to that of all SCD-associated mutants of the prenyltransferase. The results reveal that, as expected, wild-type Myc-UBIAD1 localized to the Golgi of SV-589 cells cultured in FCS (Fig. 4, panel 1). UBIAD1 (S75F), which is not associated with SCD and results from a moderately common polymorphism in the UBIAD1 gene (4, 5), also localized to the Golgi (panel 2). Consistent with our previous findings, UBIAD1 (N102S) and (G177R) were sequestered within membranes of the ER (panels 5 and 14, respectively). The remaining SCD-associated mutants of UBIAD1 were similarly defective in transport to the Golgi and localized to the ER (panels 3, 4, 6–13, and 15–22). However, it should be noted that four SCD-associated UBIAD1 mutants, D112G (panel 6), D118G (panel 7), R119G (panel 8), and N232S (panel 18), exhibited partial Golgi localization.

Fig. 4.

SCD-associated mutants of UBIAD1 are defective in trafficking from the ER to the Golgi. SV-589 cells were set up on day 0 and transfected on day 1 with 3 μg pCMV-Myc-UBIAD1 (wild-type or indicated mutant) as described in the legend to Fig. 2. Four hours after transfection, cells received a direct addition of medium A containing 10% FCS (final concentration). After 16 h at 37°C, cells were fixed and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy using IgG-9E10 (against Myc-UBIAD1) as described in the legend to Fig. 1.

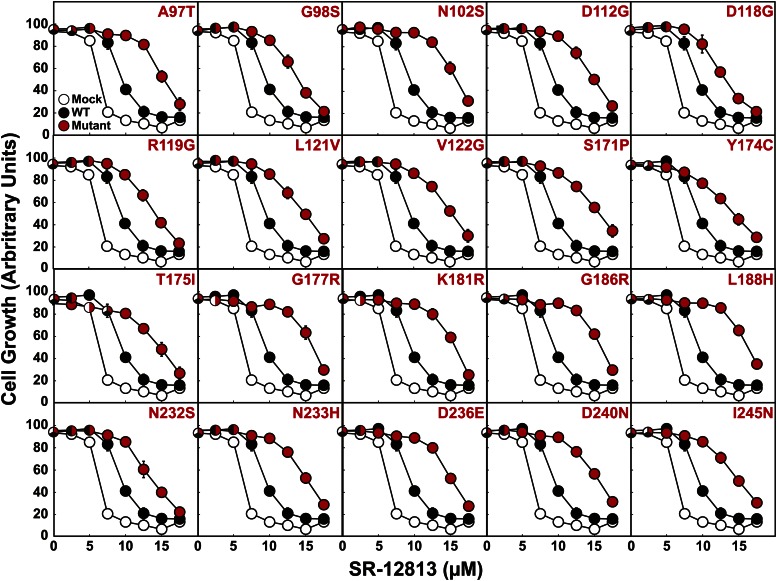

In addition to their sequestration in ER membranes of isoprenoid-replete cells, UBIAD1 (N102S) and (G177R) inhibit sterol-accelerated ERAD of reductase (12). To determine whether the other 18 SCD-associated mutants of UBIAD1 inhibit reductase ERAD, we employed SR-12813. The 1,1-bisphosphonate ester mimics sterols in accelerating reductase ERAD and prevents growth of cells in LPDS-containing medium (41), which renders them dependent on endogenous cholesterol synthesis for survival (26). Importantly, growth of CHO-7 cells (a subline of CHO-K1 cells) in the presence of SR-12813 is restored by overexpression of degradation-resistant, but not wild-type, reductase (41). Figure 5 shows that growth of mock-transfected CHO-7 cells tolerated as much as 5 μM SR-12813; proliferation was markedly reduced when cells were challenged with higher concentrations of SR-12813. Cells expressing wild-type UBIAD1 were slightly more resistant to SR-12813 and tolerated up to 7.5 μM of the drug. Overexpression of any of the SCD-associated UBIAD1 mutants markedly enhanced resistance of CHO-7 cells to growth in SR-12813. Similar results were observed in at least two independent repeat experiments, one of which is shown in supplementary Fig. 2A. Moreover, expression of SCD-associated, but not wild-type, UBIAD1 led to elevated levels of reductase, indicating slowed ERAD of the protein (supplementary Fig. 2B).

Fig. 5.

SCD-associated mutants of UBIAD1 confer resistance of CHO-7 cells to growth in the presence of SR-12813. CHO-7 cells were set up on day 0 at 4 × 105 cells per 100 mm dish in medium B containing 5% FCS. On day 1, cells were transfected with 3 μg pCMV-Myc-UBIAD1 (wild-type or indicated mutant) as described in the legend to Fig. 2. All of the plasmids contained the G418 resistance gene, neo. On day 2, the cells were switched to medium B containing 5% FCS and 0.7 mg/ml G418 and refed every 2–3 days. On day 14, the G418-resistant cells were trypsinized, washed in medium B containing 5% LPDS, and plated in triplicate at 1 × 103 cells per well of a 96-well plate containing medium B supplemented with 5% LPDS and the indicated concentration of SR-12813. The cells were refed every 2–3 days. On day 28, the wells were washed with PBS, fixed in 95% ethanol, and stained with crystal violet. The stained plates were scanned on an Epson Perfection V700 photo scanner (Long Beach, CA) in transmitted light mode at a resolution of 300 dots per inch. Images were analyzed using National Institutes of Health Image J software to determine the average pixel value from a circular area corresponding to each well. The resulting values were subtracted from the value obtained from an empty well that received no cells to yield arbitrary units corresponding to degree of growth of each condition tested.

We next examined the effect of isoprenoid depletion on retrograde transport of endogenous UBIAD1 from the Golgi to the ER over time. SV-589 cells were first cultured in the presence of FCS for 16 h to ensure localization of UBIAD1 to Golgi and subsequently treated for various periods of time with compactin. The results show that Golgi localization of endogenous UBIAD1 was inhibited after 2 h of nonsterol isoprenoid depletion with compactin (Fig. 6A, compare panels 1 and 4). Similar results were obtained in the presence of cycloheximide (Fig. 6B, compare panels 1 and 2 with 3 and 4), indicating that Golgi-localized, but not newly synthesized, UBIAD1 relocalized to the ER upon depletion of nonsterol isoprenoids. Importantly, cycloheximide did not disrupt Golgi localization of UBIAD1 in the absence of compactin (data not shown), indicating that inhibition of protein synthesis does not alter production of GGpp that promotes ER-to-Golgi transport of UBIAD1. Compactin also stimulated transport of Myc-UBIAD1 from the Golgi to the ER of SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells (Fig. 6C); retrograde transport occurred when cells were cultured in either sterol-replete FCS-containing medium (panels 1 and 2) or sterol-depleted medium containing LPDS (panels 3 and 4). This result is consistent with our previous observation that sterols do not influence subcellular localization of UBIAD1 (12).

Fig. 6.

Depletion of nonsterol isoprenoids triggers retrograde transport of UBIAD1 from the Golgi to the ER. SV-589 (A, B) and SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells (C) were set up on day 0 at 8 × 104 cells per well of 6-well plates with glass coverslips in medium A supplemented with 10% FCS. On day 1, cells were refed identical medium; some of the cells in (C) were switched to medium A containing 10% LPDS. After 16 h at 37°C, cells were incubated in the identical medium for the indicated time (A), 6 h (B), or 2 h (C) in the presence of 10 μM compactin; some of the dishes in (B) also received 50 μM cycloheximide. Following treatments, cells were fixed and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy using IgG-H8 (against endogenous UBIAD1) and IgG-9E10 (against Myc-UBIAD1) as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Scale bar is 10 microns.

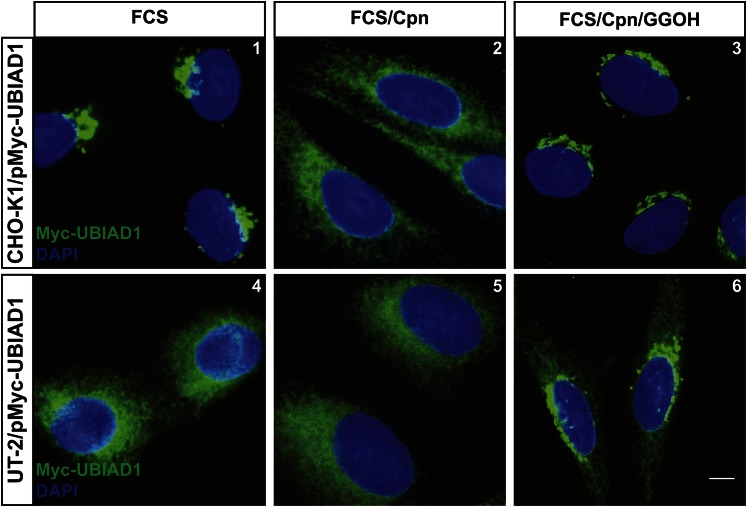

Although sterols trigger its binding to UBIAD1 in ER membranes (12), reductase does not appear to directly contribute to geranylgeranyl-regulated transport of UBIAD1 between the ER and the Golgi. CHO-K1/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells are a line of CHO-K1 cells that stably overexpress Myc-UBIAD1. When these cells were cultured in the presence of FCS, Myc-UBIAD1 localized to the Golgi (Fig. 7, panel 1). Treatment of CHO-K1/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells with compactin disrupted Golgi localization of Myc-UBIAD1, causing its retrograde transport to the ER (panel 2); Myc-UBIAD1 remained in the Golgi when compactin-treated cells also received GGOH (panel 3). Myc-UBIAD1 localized to the ER of FCS-cultured UT-2/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells (Fig. 7, panel 4), which stably overexpress the protein. This result is consistent with the mevalonate auxotrophy of reductase-deficient UT-2 cells (25). Although compactin had no effect on localization of Myc-UBIAD1 in UT-2/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells (panel 5), the addition of GGOH stimulated its transport from the ER to the Golgi (panel 6).

Fig. 7.

HMG-CoA reductase is not required for geranylgeranyl-mediated transport of UBIAD1 between the ER and the Golgi. CHO-K1/pMyc-UBIAD1 and UT-2/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells were set up on day 0 at 8 × 104 cells per well of 6-well plates with glass coverslips in medium B supplemented with 5% FCS; medium for UT-2/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells was further supplemented with 200 μM mevalonate. On day 1, cells were refed medium B containing 5% FCS (no mevalonate). After 16 h at 37°C, cells were treated for 4 h at 37°C with identical medium in the absence or presence of 10 μM compactin and 30 μM GGOH. Following treatments, cells were fixed and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy using IgG-9E10 (against Myc-UBIAD1) as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The scale bar is 5 microns.

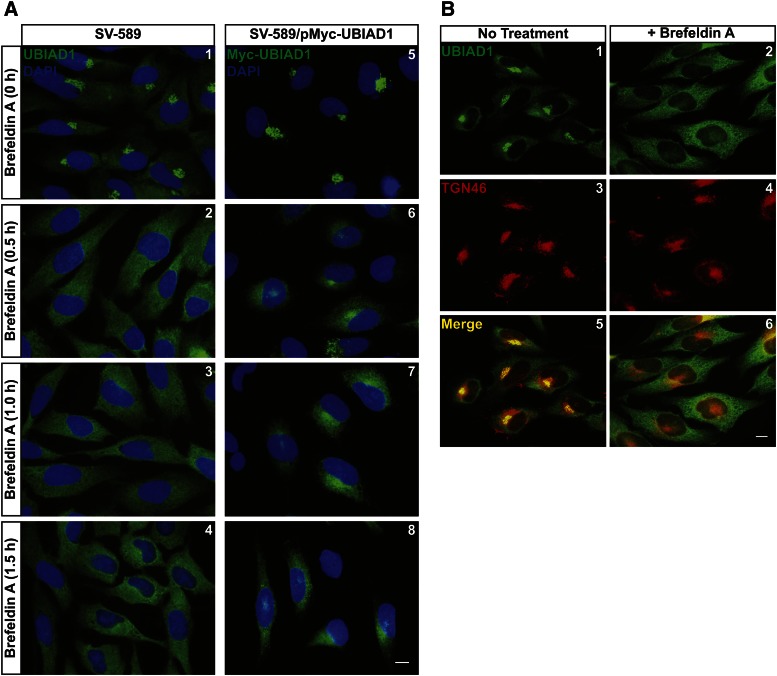

Many Golgi-resident proteins are known to continuously recycle from the Golgi to the ER (42–44). This retrograde transport can be revealed through inhibition of export from the ER, which causes Golgi-resident proteins to accumulate in the ER (43, 44). To determine whether UBIAD1 constitutively cycles between the Golgi and the ER, we began by employing the fungal metabolite, BFA. BFA inhibits GTP-exchange factors that activate the small GTPase, Arf1, which initiates recruitment of coat protein complex I to Golgi membranes for retrograde transport to the ER (45). This inhibition causes redistribution of Golgi proteins and membranes to the ER and indirectly blocks export from the organelle (46). Figure 8A shows that BFA caused redistribution of both endogenous UBIAD1 (panels 1–4) and Myc-UBIAD1 (panels 5–8) to the ER of FCS-cultured cells. The specificity of BFA is demonstrated by the observation that UBIAD1, but not TGN-localized TGN-46, accumulated in the ER following BFA treatment (Fig. 8B, compare panels 1, 3, and 5 with 2, 4, and 6).

Fig. 8.

BFA triggers relocalization of UBIAD1 from the Golgi to the ER. SV-589 and SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells were set up on day 0 at 8 × 104 cells per well of 6-well plates with glass coverslips in medium A containing 10% FCS. On day 1, cells were refed identical medium in the absence or presence of 2 μg/ml BFA. Following incubation at 37°C for the indicated period of time (A) or 0.5 h (B), cells were fixed for immunofluorescence microscopy using IgG-H8 (against endogenous UBIAD1), IgG-9E10 (against Myc-UBIAD1), and anti-TGN46 as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The scale bar is 10 microns.

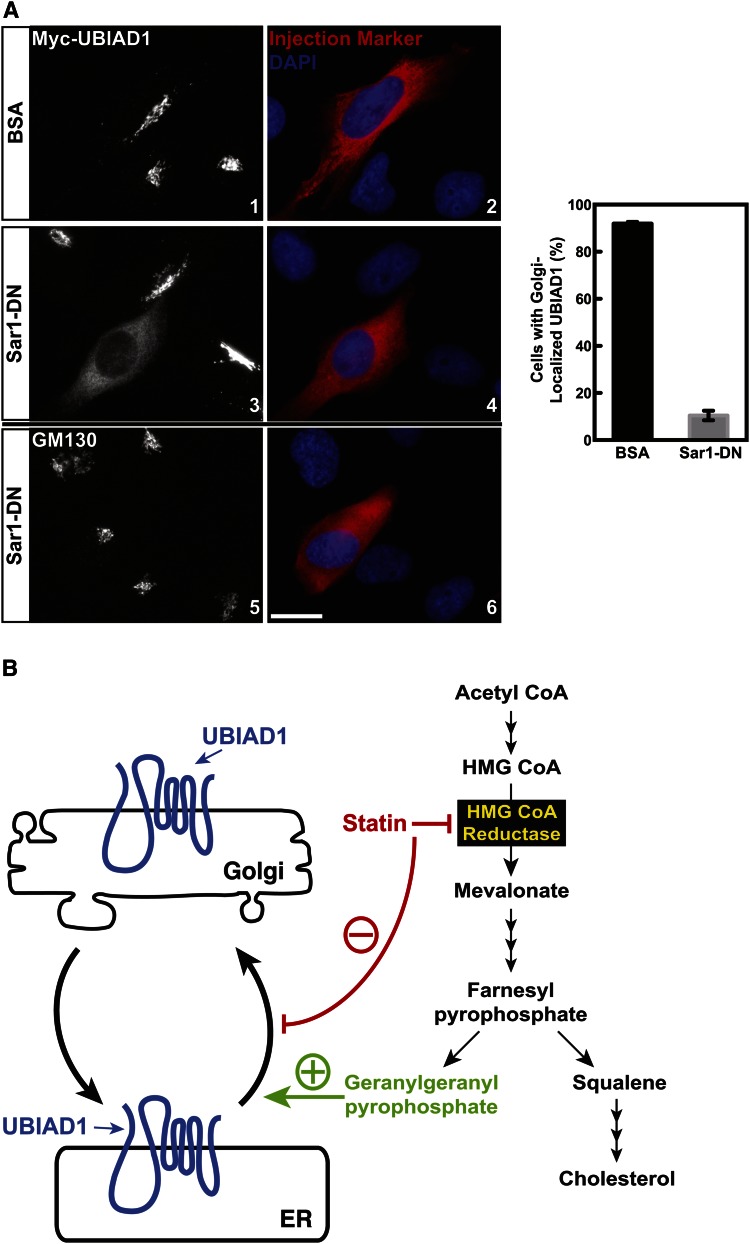

Formation of COPII vesicles, which mediate ER-to-Golgi transport of proteins, is initiated by recruitment of the GTPase, Sar1, to ER membranes (47). Membrane-associated Sar1 subsequently recruits the COPII dimers, Sec23/24 and Sec13/31, resulting in budding of vesicles from ER membranes that are destined for the Golgi. To directly inhibit ER export, we microinjected FCS-cultured SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells with GTP-restricted, dominant-negative Sar1 (H79G) (designated Sar1DN). Results of Fig. 9A show that Myc-UBIAD1 localized to Golgi membranes of SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells microinjected with BSA (panels 1 and 2). However, Myc-UBIAD1 accumulated in the ER of SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells when they were microinjected with Sar1DN (panels 3 and 4). Consistent with previous studies (48, 49), GM130 remained in the Golgi of cells microinjected with Sar1DN (Fig. 9A, panels 5 and 6).

Fig. 9.

UBIAD1 constitutively cycles between the ER and Golgi of isoprenoid-replete cells. A: SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells on glass coverslips of 6-well plates and cultured in medium A containing 10% FCS were injected with either 1 mg/ml BSA or purified Sar1DN protein and 2 mg/ml Texas-Red conjugated dextran. After 3 h at 37°C, cells were fixed for immunofluorescence microscopy using IgG-9E10 (against UBIAD1) and anti-GM130. The results are representative of four independent experiments in which an average of 102 cells per experiment (408 cells total) were injected with Sar1DN and 132 cells per experiment (528 cell total) received BSA. Approximately 92% of cells microinjected with BSA contained Golgi-localized UBIAD1 and this was reduced to 11% upon microinjection of Sar1DN as depicted in the graph next to images. The scale bar is 10 microns. B: Schematic representation of geranylgeranyl-mediated regulation of UBIAD1 transport between the ER and Golgi.

DISCUSSION

The current results provide an experimental basis for the model shown in Fig. 9B, which depicts the intracellular trafficking of UBIAD1. Consistent with our previous studies (12), depleting cells of isoprenoids caused UBIAD1 to become sequestered in membranes of the ER (Fig. 1, supplementary Fig. 1A). ER-to-Golgi transport of both endogenous and overexpressed UBIAD1 was stimulated, in a time-dependent fashion, by the addition of GGOH to cells. Notably, expression of Myc-UBIAD1 in SV-589/pMyc-UBIAD1 cells exceeds that of endogenous UBIAD1 by about 30-fold (data not shown). However, the majority of Myc-UBIAD1 remained in the ER of isoprenoid-depleted cells and kinetics of its GGOH-induced ER-to-Golgi transport were similar compared with those of endogenous UBIAD1 (Fig. 1C). Thus, sequestration of UBIAD1 in the ER of isoprenoid-depleted cells likely results from its inability to become incorporated into transport vesicles destined for the Golgi rather than from increased association with an ER retention protein, which we anticipate would become saturated upon UBIAD1 overexpression.

When added to cells, we postulate that GGOH becomes converted to GGpp, which, in turn, binds to UBIAD1 and triggers its translocation to the medial-trans Golgi (Fig. 2). This notion is supported by two lines of evidence. First, the in vitro addition of GGpp to isoprenoid-depleted membranes stimulated incorporation of UBIAD1 into ER-derived transport vesicles through a reaction that required ATP/GTP and cytosol as a source of COPII machinery (Fig. 3D, E). The second line of evidence indicating that GGpp modulates intracellular trafficking of UBIAD1 is provided by structural analyses of archaeal UbiA prenyltransferases, which revealed that isoprenyl substrates are positioned in the membrane-embedded active site between conserved aspartate-rich motifs (NDXXDXXXD and DXXXD) (10, 11). A residue corresponding to N102 in human UBIAD1 participates in coordination of Mg2+ ions that mediate interactions with the pyrophosphate group. The SCD-associated N102S mutation in UBIAD1 markedly diminishes MK-4 synthetic activity (50) and causes the mutant enzyme to become sequestered in the ER of isoprenoid-replete cells (Fig. 4) (12). Thus, we speculate that UBIAD1 (N102S) is retained in the ER of isoprenoid-replete cells owing to reduced affinity for membrane-embedded GGpp, which prevents its incorporation into ER-derived transport vesicles. Notably, the other 19 SCD-associated mutants of UBIAD1 are also sequestered in ER membranes (Fig. 4) and block reductase ERAD (Fig. 5). It will be important to determine whether these mutants remain in the ER because of their reduced affinity for either GGpp or a component of the COPII machinery that mediates ER-to-Golgi transport.

A novel feature of the model shown in Fig. 9B is retrograde transport of UBIAD1 from the Golgi to the ER. This transport was revealed through treatment of isoprenoid-replete cells with the reductase inhibitor, compactin, which caused Golgi-localized UBIAD1 to relocalize to the ER within 2 h (Fig. 6). A plausible mechanism for statin-induced Golgi-to-ER transport of UBIAD1 involves its sensing a decline in GGpp levels within Golgi membranes. As a result, UBIAD1 becomes incorporated into transport vesicles that carry the prenyltransferase back to the ER. However, evidence in support of an alternative scenario is provided by Fig. 9A, which shows that inhibition of ER export through microinjection of isoprenoid-replete cells with Sar1DN caused UBIAD1 to accumulate in the organelle. Together, these results support a mechanism whereby UBIAD1 constitutively cycles between the ER and Golgi, becoming trapped in the ER upon sensing a drop in GGpp within ER membranes (Fig. 9B).

Activation of ER membrane-bound sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs), which modulate expression of gene encoding cholesterol biosynthetic enzymes, requires transport from ER to Golgi where they encounter proteases that release transcriptionally active fragments from membranes (51, 52). This activation requires the escort protein, Scap, which mediates incorporation of SREBPs into ER-derived transport vesicles bound for the Golgi (27). Cholesterol binds to Scap, causing it to bind to Insigs, which blocks incorporation of Scap and its associated SREBPs into transport vesicles (53, 54). In the absence of ER export, SREBPs are no longer proteolytically activated and expression of its target genes declines. Thus, our current experiments describing the geranylgeranyl-mediated regulation of UBIAD1 trafficking represent the second example in which products of the cholesterol biosynthetic pathway control vesicular trafficking from the ER. This metabolic control of ER export is distinct from the quality control system that mediates retention of newly synthesized proteins in the ER until they are properly folded, assembled into oligomeric complexes, or have acquired posttranslational modifications (55). It is important to note that reductase does not directly contribute to intracellular trafficking of UBIAD1 (Fig. 7). Considering this, together with previous studies showing that sterol-induced binding of UBIAD1 to Insigs is mediated by reductase (12), we conclude that geranylgeranyl-regulated transport of UBIAD1 between the ER and the Golgi does not require the action of Insigs.

In summary, the current results indicate that UBIAD1 is a novel sensor of GGpp in ER membranes. Disruption of this sensing mechanism appears to occur in SCD and leads to the sequestration of UBIAD1 in the ER where it binds to and inhibits ERAD of reductase (Figs. 4, 5). This inhibition likely contributes to the overaccumulation of cholesterol that characterizes SCD (4, 5). Studies are now underway to expand on these observations by examining relationships between subcellular localization and enzymatic activity of UBIAD1, which will allow us to determine whether SCD-associated UBIAD1 mutants are deficient in binding to GGpp, components of the COPII machinery, or a putative escort protein. Finally, relocalization of UBIAD1 from the Golgi to the ER within 2 h of statin treatment (Fig. 6) indicates rapid turnover of regulatory pools of GGpp that govern intracellular transport of the prenyltransferase. Activities for kinases that phosphorylate isoprenols (such as GGOH) and phosphatases that dephosphorylate isoprenyl pyrophosphates (such as GGpp) have been described (56, 57). An exciting avenue for future investigation is to determine whether these enzymes mediate turnover of GGpp pools and contribute to intracellular transport of UBIAD1, regulation of reductase ERAD, and prenylation of proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Lisa Beatty, Muleya Kapaale, Hue Dao, Loren Valsin, and Ijeoma Dukes for help with tissue culture and Kate Luby-Phelps for instruction on deconvolution microscopy. They also thank Kristina Garland-Brasher and Gennipher Young for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Abbreviations:

- BFA

- brefeldin A

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary

- CMV

- cytomegalovirus

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- ERAD

- endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation

- Fpp

- farnesyl pyrophosphate

- GGOH

- geranylgeraniol

- GGpp

- geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate

- LPDS

- lipoprotein-deficient serum

- MK-4

- menaquinone-4

- SCD

- Schnyder corneal dystrophy

- SREBP

- sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- UBIAD1

- UbiA prenyltransferase domain-containing protein-1

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (HL20948 and GM090216 to R.A.D-B.; GM096070 to J.S.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The online version of this article (available at http://www.jlr.org) contains a supplement.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heide L. 2009. Prenyl transfer to aromatic substrates: genetics and enzymology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 13: 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakagawa K., Hirota Y., Sawada N., Yuge N., Watanabe M., Uchino Y., Okuda N., Shimomura Y., Suhara Y., and Okano T.. 2010. Identification of UBIAD1 as a novel human menaquinone-4 biosynthetic enzyme. Nature. 468: 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirota Y., Tsugawa N., Nakagawa K., Suhara Y., Tanaka K., Uchino Y., Takeuchi A., Sawada N., Kamao M., Wada A., et al. 2013. Menadione (vitamin K3) is a catabolic product of oral phylloquinone (vitamin K1) in the intestine and a circulating precursor of tissue menaquinone-4 (vitamin K2) in rats. J. Biol. Chem. 288: 33071–33080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orr A., Dube M. P., Marcadier J., Jiang H., Federico A., George S., Seamone C., Andrews D., Dubord P., Holland S., et al. 2007. Mutations in the UBIAD1 gene, encoding a potential prenyltransferase, are causal for Schnyder crystalline corneal dystrophy. PLoS One. 2: e685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weiss J. S., Kruth H. S., Kuivaniemi H., Tromp G., White P. S., Winters R. S., Lisch W., Henn W., Denninger E., Krause M., et al. 2007. Mutations in the UBIAD1 gene on chromosome short arm 1, region 36, cause Schnyder crystalline corneal dystrophy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48: 5007–5012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brownstein S., Jackson W. B., and Onerheim R. M.. 1991. Schnyder’s crystalline corneal dystrophy in association with hyperlipoproteinemia: histopathological and ultrastructural findings. Can. J. Ophthalmol. 26: 273–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crispin S. 2002. Ocular lipid deposition and hyperlipoproteinaemia. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 21: 169–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nickerson M. L., Bosley A. D., Weiss J. S., Kostiha B. N., Hirota Y., Brandt W., Esposito D., Kinoshita S., Wessjohann L., Morham S. G., et al. 2013. The UBIAD1 prenyltransferase links menaquinone-4 [corrected] synthesis to cholesterol metabolic enzymes. Hum. Mutat. 34: 317–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nowinska A. K., Wylegala E., Teper S., Lyssek-Boron A., Aragona P., Roszkowska A. M., Micali A., Pisani A., and Puzzolo D.. 2014. Phenotype-genotype correlation in patients with Schnyder corneal dystrophy. Cornea. 33: 497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang H., Levin E. J., Liu S., Bai Y., Lockless S. W., and Zhou M.. 2014. Structure of a membrane-embedded prenyltransferase homologous to UBIAD1. PLoS Biol. 12: e1001911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng W., and Li W.. 2014. Structural insights into ubiquinone biosynthesis in membranes. Science. 343: 878–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schumacher M. M., Elsabrouty R., Seemann J., Jo Y., and DeBose-Boyd R. A.. 2015. The prenyltransferase UBIAD1 is the target of geranylgeraniol in degradation of HMG CoA reductase. eLife. 4: 05560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein J. L., and Brown M. S.. 1990. Regulation of the mevalonate pathway. Nature. 343: 425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang F. L., and Casey P. J.. 1996. Protein prenylation: molecular mechanisms and functional consequences 3. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 65: 241–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sever N., Yang T., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L., and DeBose-Boyd R. A.. 2003. Accelerated degradation of HMG CoA reductase mediated by binding of insig-1 to its sterol-sensing domain. Mol. Cell. 11: 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sever N., Song B. L., Yabe D., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S., and DeBose-Boyd R. A.. 2003. Insig-dependent ubiquitination and degradation of mammalian 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase stimulated by sterols and geranylgeraniol. J. Biol. Chem. 278: 52479–52490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song B. L., Sever N., and DeBose-Boyd R. A.. 2005. Gp78, a membrane-anchored ubiquitin ligase, associates with Insig-1 and couples sterol-regulated ubiquitination to degradation of HMG CoA reductase. Mol. Cell. 19: 829–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jo Y., Lee P. C., Sguigna P. V., and DeBose-Boyd R. A.. 2011. Sterol-induced degradation of HMG CoA reductase depends on interplay of two Insigs and two ubiquitin ligases, gp78 and Trc8. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108: 20503–20508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu T. F., Tang J. J., Li P. S., Shen Y., Li J. G., Miao H. H., Li B. L., and Song B. L.. 2012. Ablation of gp78 in liver improves hyperlipidemia and insulin resistance by inhibiting SREBP to decrease lipid biosynthesis. Cell Metab. 16: 213–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elsabrouty R., Jo Y., Dinh T. T., and DeBose-Boyd R. A.. 2013. Sterol-induced dislocation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase from membranes of permeabilized cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 24: 3300–3308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morris L. L., Hartman I. Z., Jun D. J., Seemann J., and DeBose-Boyd R. A.. 2014. Sequential actions of the AAA-ATPase valosin-containing protein (VCP)/p97 and the proteasome 19 S regulatory particle in sterol-accelerated, endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-associated degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 289: 19053–19066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rowe T., and Balch W. E.. 1995. Expression and purification of mammalian Sarl. Methods Enzymol. 257: 49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein J. L., Basu S. K., and Brown M. S.. 1983. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of low-density lipoprotein in cultured cells. Methods Enzymol. 98: 241–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamamoto T., Davis C. G., Brown M. S., Schneider W. J., Casey M. L., Goldstein J. L., and Russell D. W.. 1984. The human LDL receptor: a cysteine-rich protein with multiple Alu sequences in its mRNA. Cell. 39: 27–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosley S. T., Brown M. S., Anderson R. G., and Goldstein J. L.. 1983. Mutant clone of Chinese hamster ovary cells lacking 3-hydroxy-3 -methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 258: 13875–13881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Metherall J. E., Goldstein J. L., Luskey K. L., and Brown M. S.. 1989. Loss of transcriptional repression of three sterol-regulated genes in mutant hamster cells. J. Biol. Chem. 264: 15634–15641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nohturfft A., Yabe D., Goldstein J. L., Brown M. S., and Espenshade P. J.. 2000. Regulated step in cholesterol feedback localized to budding of SCAP from ER membranes. Cell. 102: 315–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diao A., Rahman D., Pappin D. J., Lucocq J., and Lowe M.. 2003. The coiled-coil membrane protein golgin-84 is a novel rab effector required for Golgi ribbon formation. J. Cell Biol. 160: 201–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Song B. L., and DeBose-Boyd R. A.. 2004. Ubiquitination of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase in permeabilized cells mediated by cytosolic E1 and a putative membrane-bound ubiquitin ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 28798–28806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rexach M. F., and Schekman R. W.. 1991. Distinct biochemical requirements for the budding, targeting, and fusion of ER-derived transport vesicles. J. Cell Biol. 114: 219–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rowe T., Aridor M., McCaffery J. M., Plutner H., Nuoffer C., and Balch W. E.. 1996. COPII vesicles derived from mammalian endoplasmic reticulum microsomes recruit COPI. J. Cell Biol. 135: 895–911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang Y., Motamed M., Seemann J., Brown M. S., and Goldstein J. L.. 2013. Point mutation in luminal loop 7 of Scap protein blocks interaction with loop 1 and abolishes movement to Golgi. J. Biol. Chem. 288: 14059–14067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nohturfft A., DeBose-Boyd R. A., Scheek S., Goldstein J. L., and Brown M. S.. 1999. Sterols regulate cycling of SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) between endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 96: 11235–11240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Llopis J., McCaffery J. M., Miyawaki A., Farquhar M. G., and Tsien R. Y.. 1998. Measurement of cytosolic, mitochondrial, and Golgi pH in single living cells with green fluorescent proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95: 6803–6808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banting G., and Ponnambalam S.. 1997. TGN38 and its orthologues: roles in post-TGN vesicle formation and maintenance of TGN morphology. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1355: 209–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakamura N., Rabouille C., Watson R., Nilsson T., Hui N., Slusarewicz P., Kreis T. E., and Warren G.. 1995. Characterization of a cis-Golgi matrix protein, GM130. J. Cell Biol. 131: 1715–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thyberg J., and Moskalewski S.. 1985. Microtubules and the organization of the Golgi complex. Exp. Cell Res. 159: 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shima D. T., Haldar K., Pepperkok R., Watson R., and Warren G.. 1997. Partitioning of the Golgi apparatus during mitosis in living HeLa cells. J. Cell Biol. 137: 1211–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barlowe C. K., and Miller E. A.. 2013. Secretory protein biogenesis and traffic in the early secretory pathway. Genetics. 193: 383–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jensen D., and Schekman R.. 2011. COPII-mediated vesicle formation at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 124: 1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sever N., Lee P. C. W., Song B. L., Rawson R. B., and DeBose-Boyd R. A.. 2004. Isolation of mutant cells lacking Insig-1 through selection with SR-12813, an agent that stimulates degradation of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-Coenzyme A reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 43136–43147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cole N. B., Ellenberg J., Song J., DiEuliis D., and Lippincott-Schwartz J.. 1998. Retrograde transport of Golgi-localized proteins to the ER. J. Cell Biol. 140: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Storrie B., White J., Rottger S., Stelzer E. H., Suganuma T., and Nilsson T.. 1998. Recycling of Golgi-resident glycosyltransferases through the ER reveals a novel pathway and provides an explanation for nocodazole-induced Golgi scattering. J. Cell Biol. 143: 1505–1521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sengupta P., Satpute-Krishnan P., Seo A. Y., Burnette D. T., Patterson G. H., and Lippincott-Schwartz J.. 2015. ER trapping reveals Golgi enzymes continually revisit the ER through a recycling pathway that controls Golgi organization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 112: E6752–E6761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nebenführ A., Ritzenthaler C., and Robinson D. G.. 2002. Brefeldin A: deciphering an enigmatic inhibitor of secretion. Plant Physiol. 130: 1102–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lippincott-Schwartz J., Yuan L. C., Bonifacino J. S., and Klausner R. D.. 1989. Rapid redistribution of Golgi proteins into the ER in cells treated with brefeldin A: evidence for membrane cycling from Golgi to ER. Cell. 56: 801–813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.D’Arcangelo J. G., Stahmer K. R., and Miller E. A.. 2013. Vesicle-mediated export from the ER: COPII coat function and regulation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1833: 2464–2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bartz R., Sun L. P., Bisel B., Wei J. H., and Seemann J.. 2008. Spatial separation of Golgi and ER during mitosis protects SREBP from unregulated activation. EMBO J. 27: 948–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seemann J., Jokitalo E., Pypaert M., and Warren G.. 2000. Matrix proteins can generate the higher order architecture of the Golgi apparatus. Nature. 407: 1022–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hirota Y., Nakagawa K., Sawada N., Okuda N., Suhara Y., Uchino Y., Kimoto T., Funahashi N., Kamao M., Tsugawa N., et al. 2015. Functional characterization of the vitamin K2 biosynthetic enzyme UBIAD1. PLoS One. 10: e0125737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goldstein J. L., DeBose-Boyd R. A., and Brown M. S.. 2006. Protein sensors for membrane sterols. Cell. 124: 35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeBose-Boyd R. A., Brown M. S., Li W. P., Nohturfft A., Goldstein J. L., and Espenshade P. J.. 1999. Transport-dependent proteolysis of SREBP: relocation of site-1 protease from Golgi to ER obviates the need for SREBP transport to Golgi. Cell. 99: 703–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Radhakrishnan A., Sun L. P., Kwon H. J., Brown M. S., and Goldstein J. L.. 2004. Direct binding of cholesterol to the purified membrane region of SCAP; mechanism for a sterol-sensing domain. Mol. Cell. 15: 259–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sun L. P., Seemann J., Goldstein J. L., and Brown M. S.. 2007. Sterol-regulated transport of SREBPs from endoplasmic reticulum to Golgi: Insig renders sorting signal in Scap inaccessible to COPII proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104: 6519–6526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Guerriero C. J., and Brodsky J. L.. 2012. The delicate balance between secreted protein folding and endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation in human physiology. Physiol. Rev. 92: 537–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Crick D. C., Andres D. A., and Waechter C. J.. 1997. Novel salvage pathway utilizing farnesol and geranylgeraniol for protein isoprenylation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 237: 483–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miriyala S., Subramanian T., Panchatcharam M., Ren H., McDermott M. I., Sunkara M., Drennan T., Smyth S. S., Spielmann H. P., and Morris A. J.. 2010. Functional characterization of the atypical integral membrane lipid phosphatase PDP1/PPAPDC2 identifies a pathway for interconversion of isoprenols and isoprenoid phosphates in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285: 13918–13929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.