Abstract

Study Objectives:

Despite the considerable prevalence of the nightmare disorder and its burden on the patient, nightmares are underdiagnosed and undertreated, even in sleep centers.

Methods:

A total of 1,125 patients in a sleep center undergoing routine diagnostic procedures for their sleep disorders completed a questionnaire about nightmares.

Results:

About 20% of the sample indicated an interest in more information about nightmare etiology and nightmare therapy—even patients who had never sought professional help previously.

Conclusions:

From a clinical viewpoint, health care professionals should be encouraged to ask about nightmares and, as a first step, internet-based self-help programs should be implemented for this patient group.

Citation:

Schredl M, Dehmlow L, Schmitt J. Interest in information about nightmares in patients with sleep disorders. J Clin Sleep Med 2016;12(7):973–977.

Keywords: nightmare disorder, imagery rehearsal therapy

INTRODUCTION

Nightmares are defined as extended, extremely dysphoric, and well-remembered dreams that usually involve threat to survival, security, or physical integrity.1 Nightmares are experienced occasionally by many persons during their lifetime,2 i.e., for the clinical context, it is important to differentiate between nightmares that occur rarely and the presence of a nightmare disorder (which includes the criteria that nightmares cause clinically significant distress and/or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning).1 The nightmare disorder prevalence in the general population is estimated to be about 5%,3 and about 30% in a patient group with various mental disorders.4 The etiology of nightmares is best explained by a disposition-stress model5 and effective treatment strategies, like Imagery Rehearsal Therapy, are available.6 Nightmares are also of special importance in a clinical context because nightmares are an independent predictor of suicidal ideation and suicide.7–9

Despite the considerable prevalence of the nightmare disorder3 and its burden on the patient,10 nightmares have been rarely diagnosed and treated, even in sleep clinics: Krakow reported that 16.3% of sleep-disordered patients (n = 718) also have a salient nightmare condition that normally would not have been diagnosed if they had not specifically asked for it as part of this research project.11 Comparable results were reported by Schredl et al.,12 who found that 13.4% of the patients undergoing diagnostic procedures for various reasons in a sleep laboratory (n = 4,001) reported nightmares at least once a week, whereas a diagnosis of a nightmare disorder was given to only 1.6% of the sample. On the other hand, nightmare sufferers also rarely seek help for their problem on their own initiative.13–16 In an online study of nightmare sufferers (n = 335), only 29.6% of the respondents reported that they had asked a health care provider for help.13 Even lower figures were reported for persons of a representative sample having nightmares at least once a week (15.19%)15 or students with relevant nightmare disorder symptoms (11.11%).14 Among the findings that increased nightmare frequency is correlated with a higher probability to seek professional help,14,15 no effects of gender, age, and education on this variable were reported.15,16 If professional help was sought, only 31.76% of the respondents rated it as beneficial,16 and the percentage (19%) was even lower in the online study of nightmare sufferers.13 In addition, about one-third of the students believed that nightmares are a treatable conditions, and this belief was less likely in individuals with relevant nightmare symptoms.14 To summarize, health care professionals underdiagnose nightmare disorder in their patients and nightmare sufferers relatively seldom ask for help, indicating that a major portion of this patient group is not being treated adequately.

BRIEF SUMMARY

Current Knowledge/Study Rationale: Recent studies indicate that nightmares are underdiagnosed and undertreated, even in sleep medicine centers. The aim of the present study was to determine the percentage of patients who are interested in information about nightmares regarding etiology and therapy.

Study Impact: The findings of the present study clearly indicate that there is a considerable number of sleep-disordered patients in need of nightmare counseling. It is thus highly recommended that questions about nightmare frequency and nightmare distress be included in the diagnostic procedures at every sleep center.

This study addressed the following question: What proportion of patients reporting the experiencing of nightmares would be interested in receiving information about nightmare etiology and nightmare treatment, in addition to the clinical diagnostic processes in a sleep medicine clinic (i.e., is this patient group willing to make use of such a counseling service if offered explicitly to them)?

METHODS

Participants

Eleven hundred twenty-five patients (686 men, 439 women) with sleep-related complaints who underwent polysomnographic diagnostic procedures in one of two sleep laboratories were included in the study. The data of 378 patients stemming from the Central Institute of Mental Health, Mannheim, a sleep center with neurological and psychiatric expertise and 747 data sets from the Theresienkrankenhaus Mannheim (pneumological-oriented sleep center) were included in the study. The mean age of the total group was 52.67 ± 14.88 years (42.53 ± 15.02 years at the Central Institute of Mental Health and 57.81 ± 11.88 years at the Theresienkrankenhaus).

Research Instruments

Nightmare frequencies were measured using an 8-point frequency scale (0 = never, 1 = less than once a year, 2 = about once a year, 3 = about 2 to 4 times a year, 4 = about once a month, 5 = 2 to 3 times a month, 6 = about once a week, and 7 = several times a week). A specific definition for nightmares was not given in this study. Re-test reliability (4 week-interval) of the scale was high (r = 0.75).17 To determine the distress associated with the nightmares, a 5-point scale “If you currently experience nightmares, how distressing are they?” (0 = None, 1 = Low, 2 = Medium, 3 = High, and 4 = Very high) was presented. The retest reliability of this scale over a 2-week interval was r = 0.673.2

Furthermore, the participants were asked whether they experience recurrent nightmares that were related to events that the patients had actually experienced in waking life. If so, they were supposed to write down what kind of event it was. For descriptive purposes, the topics of this open question were post hoc classified into categories. In addition, an item measured whether they had sought professional help due to their nightmares in the past and, if so, what kind of help it was. Lastly, the patients were to state if they are interested in telephone counseling that would include further information about nightmare etiology and nightmare treatment, i.e., a brief version of the Imagery Rehearsal Therapy.3 If so, they were to fill in their address and telephone number.

Procedure

All patients within the study period were asked to fill out the questionnaire prior to their first night in the sleep laboratory which was embedded within the standard diagnostic routines. In the sleep centre of the Theresienkrankenhaus, about 200 questionnaires were left blank, i.e., the response rate was about 79%. About 80 questionnaires were not completed by the patients of the sleep center of the Central Institute of Mental Health, resulting in a response rate of about 83%. Unfortunately, it was not possible to conduct the telephone sessions due to the very limited personnel resources of the research group at that time. To examine the effects of sociodemographic variables (age, gender), nightmare frequency, and nightmare distress on the “seeking help for nightmares” variable and the “telephone counselling” variable (both binary), logistic regressions procedure was used. Ordinal regressions were computed for nightmare frequency and nightmare distress. For this pilot study, the patients' diagnoses and medications were not elicited.

RESULTS

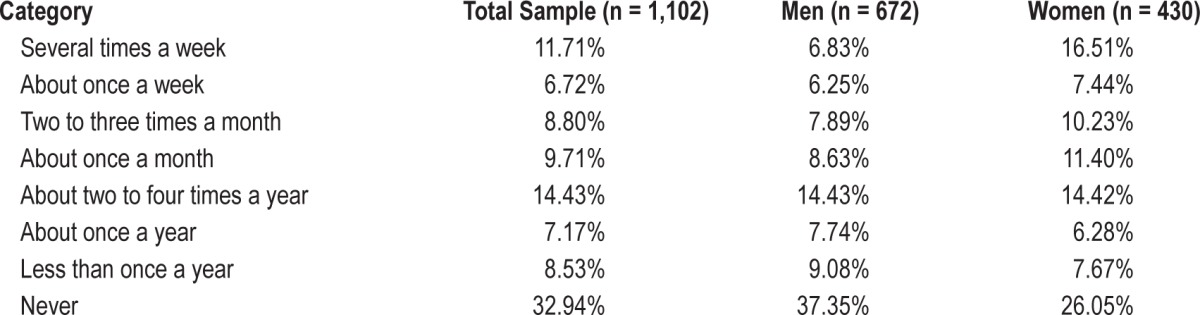

Table 1 shows the distribution of nightmare frequencies for the entire sample. About 18% of the patients stated that they had nightmares at least once a week. The logistic regression indicated that age (standardized estimate: −0.1527, χ2 = 26.3, p < 0.0001) and gender (standardized estimate: 0.1550, χ2 = 27.3, p < 0.0001) had an effect on nightmare frequency, with older persons reporting nightmares less often than younger persons, and women more than men. Nightmare distress was distributed as follows: Very high (4.24%), High (12.48%), Medium (19.85%), Low (27.84%), and None (35.85%) (n = 801 valid answers). A total of 14.66% of the participants (n = 989 valid answers) reported recurrent nightmares that refer to events that had happened in real life (death of close persons, partnership problems, domestic violence, workplace bullying, sexual abuse, childhood abuse, accidents, war experiences, and other topics). The frequent nightmares subgroup (once per week or more often) showed a higher proportion of persons who claimed that they had recurrent dreams (36.04%, n = 197).

Table 1.

Nightmare frequency scale.

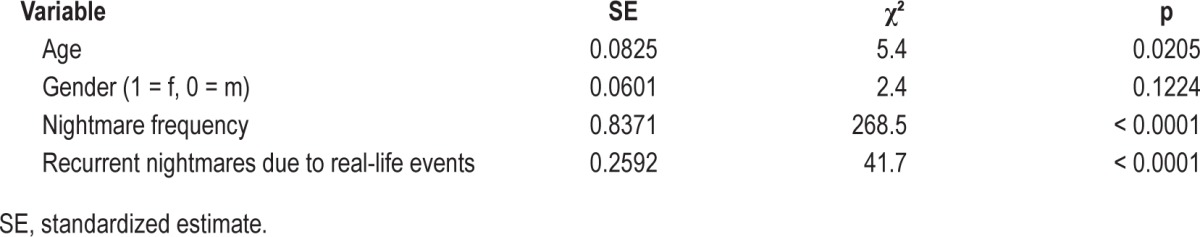

As shown in Table 2, nightmare distress was highly correlated with nightmare frequency. In addition to nightmare frequency, experiencing recurrent nightmares with reference to real-life events was related to increased nightmare distress. There was no gender effect, but older persons tended to experience slightly more distress than younger persons (Table 2).

Table 2.

Ordinal regression of nightmare distress (n = 762).

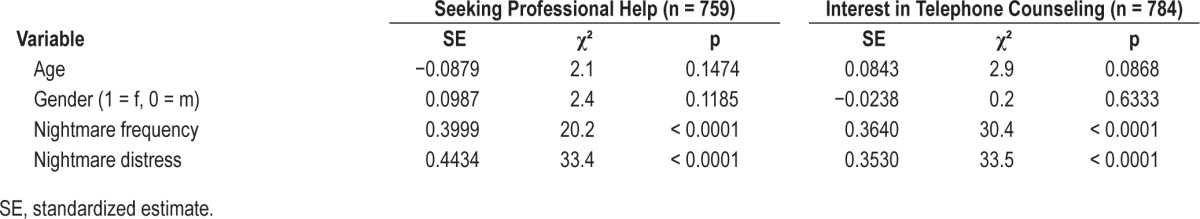

Overall, 12.24% of 972 participants with valid answers for this item reported that they had sought help for their nightmares. The figure for the patients with frequent nightmares (once a week or more often) was higher (33.00%). The open questions were answered by 117 participants. The largest group of healthcare professionals that were asked for help were psychologists/psychotherapists (about 70%), psychiatrists (about 10%), general practitioners (about 6%), sleep specialists (about 5%); the rest were not further specified. Whereas age and gender were not related to having sought help for nightmares, nightmare frequency and nightmare distress had a significant impact (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Logistic regression of “seeking professional help” and “interest in telephone counseling” variables.

About 20.80% of the participants were interested in the offered telephone counselling and filled in their contact data. The figures did not differ between the 2 sleep centers: 20.75% (Theresienkrankenhaus) and 20.90% (Central Institute of Mental Health). About 46.80% of the individuals with frequent nightmares (once a week or more often) expressed their interest in telephone counselling. Similar to the analysis of the seeking help variable, the interest in the telephone counselling was not related to age and gender but to nightmare frequency and nightmare distress (Table 3). A similar analysis for the 202 participants with frequent nightmares (once a week or more often) showed the same result: age and gender were not related to the interest in the telephone counselling but nightmare distress was. Interestingly, 158 patients (16.26% of all participants who completed both items regarding seeking help and interest in telephone counselling) who had never sought help for their nightmares previously were interested in the counselling offer.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence rate of persons undergoing sleep laboratory diagnostic procedures with frequent nightmares (18%) is in line with previous findings.11,12 Also, the relatively low percentage of persons with frequent nightmares (33%) who have sought professional help for their condition has been reported previously.13–16 The new finding is the high percentage of patients who are interested in obtaining more information about nightmare etiology and nightmare therapy, including patients who never sought help before.

The responder rate of the study was quite high in both sleep labs, i.e., even if all persons who did not participate are not interested in information about nightmares, the estimated percentage for the total populations of patients with sleep disorders would still be around 16%. It has to be added that the impression was that a considerable number of persons did not participate in the study due to language problems (reading German was too difficult for them). Even though no diagnoses were elicited in this pilot study, the finding that the percentages for persons who are interested in more information about nightmares did not differ between a neurological/psychiatric sleep center and a pneumological sleep center indicated that the primary diagnosis which led to the admission to the sleep lab might have played a minor role. For a follow-up study, it would be interesting to elicit all diagnoses of the patients since, for example, it has been shown that comorbid depression correlates with nightmare frequency in patients with sleep apnea.18,19 The finding that age and gender is not related to the “telephone counselling” variable also supports the notion that the primary diagnosis for admission to the sleep lab might not be the main influencing factor since men more often undergo diagnostic procedures for sleep-related breathing disorders and younger persons more often for different types of hypersomnia; for age and gender distribution in German sleep centers, see Schredl et al.12

A limitation of the study is that no specific definition for nightmare was provided. One might hypothesize that this might lead to overestimations regarding nightmare frequency since participants might also include very distressing bad dreams without awakenings.20 However, this methodological issue is not in particular relevant regarding the main findings of the study about the percentage of persons who sought help or are interested in information about nightmares. As the awakening criterion is no longer in the focus of the diagnostic criteria of the nightmare disorder as defined in the ICSD-3,1 the main focus should be on persons with nightmares (or bad dreams) who experience clinically significant distress and impairment in different areas of daytime functioning.

Overall, nightmare occurrence (about two-thirds of the participants) was higher than representative German samples21,22 in which the percentage of persons who have never experienced nightmare is roughly about 50%. This increased nightmare occurrence in patients with sleep disorders has been reported previously.12 The findings that nightmare frequency decreases with age and women tend to report more nightmares are in line with previous population-based German samples2,21,22 and a large sample of patients with sleep disorders,12 thus supporting the validity of the present findings. It has to be noted that the findings regarding the decrease of nightmare frequency with age conflicts with some studies,21,23 but the gender difference is well-documented.24 The percentage of individuals with frequent nightmares having sought professional help (33%) is also in line with previous studies,13–16 but interestingly, a considerable number of patients consulting a sleep clinic and suffering from nightmares have asked psychotherapists/psychologist for help—in contrast to the findings of an online study of nightmare sufferers of whom none consulted a psychologist.13 In this study, the participants were not asked whether the consultation was beneficial for the patient. As previous studies indicate that the percentage of patients who successfully received help by professional health care providers is rather small (below 30%), it would be very interesting to follow up this topic in future studies.

Regarding nightmare distress, nightmare frequency was the major influencing factor, which is in line with previous studies.5 However, if the themes of the nightmares were related to waking-life events, the distress was rated even higher. Looking at the list of waking-life events, it should be noted that it seems plausible that not all the nightmares (e.g., those related to partnership problems) have been posttraumatic (for definitions see Wittman25). Nevertheless, this finding indicates that it would make sense to include questions about the relationship between nightmare content and waking-life events, and—in more sophisticated studies—include a diagnostic interview for posttraumatic stress disorder.

As reported by Nadorff et al.,14 the percentage of persons with a relevant nightmare disorder who ever sought professional help is low, about one-third of this group—a figure also reported by two other recent studies.13,16 For the student sample in Nadorff's study, the percentage was even lower (about 11%), clearly indicating that screening for nightmares is very important, especially in young adults.

As stated above, there was no gender or age effect on the “telephone counselling” incidence, i.e., there is not a specific group (e.g., women or young people) who were especially interested. From a clinical viewpoint it is of interest that both nightmare frequency and nightmare distress variables contributed to the desire to learn more about nightmare etiology and nightmare therapy.

To summarize, the present study replicated the findings that nightmares are underdiagnosed and undertreated and also showed that a specific offer—in this case to patients undergoing diagnostic procedures in a sleep center—can reach nightmare sufferers who have rarely or never sought professional help for their condition. As it is difficult in Germany to provide telephone counselling, it might be an option to offer these patients internet-based self-help therapy as a first step—the effectiveness of such programs has been shown.26–28 Clinicians, whether they are working in sleep medicine or other areas of professional health care, should be encouraged to ask specifically about nightmare frequency and nightmare distress, and they should be informed about effective therapeutic approaches like imagery rehearsal.6,29,30

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. The authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest. The study did not include off-label or investigational use of any medication.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 3rd ed. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. The international classification of sleep disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schredl M, Berres S, Klingauf A, Schellhaas S, Göritz AS. The Mannheim Dream questionnaire (MADRE): retest reliability, age and gender effects. Int J Dream Res. 2014;7:141–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schredl M. Nightmare disorder. In: Kushida C, editor. Nightmare disorder. Academic Press; 2013. pp. 219–24. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swart ML, van Schagen AM, Lancee J, van den Bout J. Prevalence of nightmare disorder in psychiatric outpatients. Psychother Psychosom. 2013;82:267–8. doi: 10.1159/000343590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Levin R, Nielsen TA. Disturbed dreaming, posttraumatic stress disorder, and affect distress: a review and neurocognitive model. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:482–528. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.3.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Augedal AW, Hansen KS, Kronhaug CR, Harvey AG, Pallesen S. Randomized controlled trials of psychological and pharmacological treatments for nightmares: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;7:143–52. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nadorff MR, Nazem S, Fiske A. Insomnia symptoms, nightmares, and suicidal ideation in a college student sample. Sleep. 2011;34:93–98. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.1.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanskanen A, Tuomilehto J, Viinamäki H, Vartiainen E, Lehtonen J, Puska P. Nightmares as predictors of suicide. Sleep. 2001;24:844–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sjöström N, Hetta J, Waern M. Persistent nightmares are associated with repeat suicide attempt: a prospective study. Psychiatr Res. 2009;170:208–11. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Köthe M, Pietrowsky R. Behavioral effects of nightmares and their correlations to peronality patterns. Dreaming. 2001;11:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krakow B. Nightmare complaints in treatment-seeking patients in clinical sleep medicine settings: diagnostic and treatment implications. Sleep. 2006;29:1313–9. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.10.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schredl M, Binder R, Feldmann S, et al. Dreaming in patients with sleep disorders: a multicenter study. Somnologie. 2012;16:32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thünker J, Norpoth M, Aspern Mv, Özcan T, Pietrowsky R. Nightmares: knowledge and attitudes in health care providers and nightmare sufferers. J Public Health Epidemiol. 2014;6:223–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nadorff MR, Nadorff DK, Germain A. Nightmares: under-reported, undetected, and therefore untreated. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11:747–50. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schredl M. Seeking professional help for nightmares: a representative study. Eur J Psychiatry. 2013;27:259–64. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schredl M, Göritz AS. Umgang mit Alpträumen in der Allgemeinbevölkerung: Eine Online-Studie. Psychother Med Psychol (Stuttg) 2014;64:192–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1357131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stumbrys T, Erlacher D, Schredl M. Reliability and stability of lucid dream and nightmare frequency scales. Int J Dream Res. 2013;6:123–6. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schredl M, Schmitt J. Dream recall frequency and nightmare frequency in patients with sleep disordered breathing. Somnologie. 2009;13:12–7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schredl M, Schmitt J, Hein G, Schmoll T, Eller S, Haaf J. Nightmares and oxygen desaturations: is sleep apnea related to heightened nightmare frequency? Sleep Breath. 2006;10:203–9. doi: 10.1007/s11325-006-0076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zadra AL, Donderi DC. Nightmares and bad dreams: their prevalence and relationship to well-being. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:273–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schredl M. Nightmare frequency and nightmare topics in a representative German sample. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;260:565–70. doi: 10.1007/s00406-010-0112-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schredl M. Nightmare frequency in a representative German sample. Int J Dream Res. 2013;6:119–22. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandman N, Valli K, Kronholm E, et al. Nightmares: prevalence among the Finnish general adult population and war veterans during 1972-2007. Sleep. 2013;36:1041–50. doi: 10.5665/sleep.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schredl M, Reinhard I. Gender differences in nightmare frequency: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:115–21. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wittmann L, Schredl M, Kramer M. The role of dreaming in posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76:25–39. doi: 10.1159/000096362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lancee J, Spoormaker VI, van den Bout J. Cognitive-behavioral self-help treatment for nightmares: a randomized controlled trial. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79:371–7. doi: 10.1159/000320894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Böckermann M, Gieselmann A, Sorbi M, Pietrowsky R. Entwicklung und evaluation einer internetbasierten begleiteten seibsthilfe-intervention zur bewaltigung von albtraumen. Z Klin Psychol Psychiatr Psychother. 2015;63:117–24. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lancee J, Spoormaker VI, Van den Bout J. Long-term effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural self-help intervention for nightmares. J Sleep Res. 2011;20:454–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hansen K, Höfling V, Kröner-Borowik T, Stangier U, Steil R. Efficacy of psychological interventions aiming to reduce chronic nightmares: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33:146–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krakow B, Zadra AL. Clinical management of chronic nightmares: imagery rehearsal therapy. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4:45–70. doi: 10.1207/s15402010bsm0401_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]