Abstract

Objective

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is highly prevalent among U.S. Spanish-speaking Latinos, but the lack of empirically-supported treatments precludes this population’s access to quality mental health care.

Method

Following the promising results of an open-label trial of the Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression (BATD) among Spanish-speaking Latinos, we conducted a randomized control trial (RCT; N = 46) that compared BATD to supportive counseling. Study outcomes included depression, BATD proposed mechanisms of change, and non-specific psychotherapy factors.

Results

Relative to supportive counseling, BATD led to greater decreases in depressive symptoms over time (p = 0.04) and greater MDD remission at the end of treatment (p = 0.01). Activity level (p = 0.01) and environmental reward (p = 0.05) showed greater increases over time among those who received BATD compared to supportive counseling. Treatment adherence, therapeutic alliance, and treatment satisfaction did not differ between the groups over time (ps > 0.17). The one-month follow-up suggested sustained clinical gains across therapies.

Conclusions

The current study adds to a growing treatment literature and provides support that BATD is efficacious in reducing depression and increasing activity level and environmental reward in the largest, yet historically underserved U.S. ethnic minority population. This trial sets the stage for a larger RCT that evaluates the transportability and generalizability of BATD in an effectiveness trial.

Keywords: Behavioral activation, supportive counseling, Latinos, Spanish-speaking, depression

U.S. Latinos show pronounced patterns of mental health treatment underutilization and attrition (Blanco et al., 2007). Moreover, Latinos with a Spanish-speaking preference (LSSP) receive less depression treatment than those who prefer English, even after accounting for disorder severity, time in the U.S., and logistical barriers (Keyes et al., 2012). In a time that emphasizes broader access to mental healthcare, it is imperative to develop psychotherapies that address the needs of this underserved population.

Emerging evidence supports behavioral activation for use with LSSP. Behavioral Activation is an empirically-supported approach (Sturmey, 2009) rooted on learning theories and suggests that depression occurs when depressive behaviors, but not healthy, positive behaviors are reinforced (Ferster, 1973). Through treatment, clients understand the behavior-mood association and engage in pleasurable activities to decrease depression. Behavioral Activation has been argued to be beneficial among Latinos because its rationale attributes depression to environmental and not cognitive or biological factors, which decreases stigma (Santiago-Rivera et al., 2008). A recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluated a culturally-modified BA (n = 21) against treatment as usual (n = 22) and supported the efficacy of Behavioral Activation among Latinos in reducing depression (Kanter et al., 2014). Despite its promise, the study carried noteworthy limitations including unbalanced attrition in the treatment as usual condition, a non-standardized treatment as usual condition, and no examination of change in proposed BA mediators.

Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression (BATD; Lejuez et al., 2011) is a brief, 10-week BA version that has shown to improve retention among underserved populations relative to treatment as usual (e.g., Magidson et al., 2011) and more recently, it showed promising results in a sample of LSSP. In an open-label trial, individuals’ depressive symptoms decreased and mechanisms of BATD (i.e., activation and environmental reward) increased. Participants completed 88% of total sessions. An in-depth interview showed high treatment acceptability and no need for changes to BATD’s content, cultural or otherwise (Collado et al., 2014)1.

Within this framework, the goal of this RCT was to evaluate BATD against Supportive Counseling (SC) as a credible control condition to account for non-specific treatment components, such as therapeutic alliance, therapist contact time, and rudimentary aspects of cultural responsiveness. We hypothesized that relative to SC, BATD would lead to: 1. greater reductions in depressive symptoms, 2. a higher percentage of MDD remission, 3. greater increases in activation and environmental reward, and 4. greater treatment adherence. As secondary goals, we examined group differences on therapeutic alliance, treatment satisfaction, and treatment adherence. Finally, we conducted a one-month follow-up and expected BATD to lead to sustained clinical gains relative to SC.

Method

Procedures and Design

A sample of LSSP (N = 46) was recruited from July 2013 to June 2014 primarily through community organizations and radio stations serving the Spanish-speaking community of the [area]. Initial eligibility was determined in a telephone screener, which included questions from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (SCID-IV; Collado et al., 2014) was the translation of the most recent BATD manual (see First, Spitzer, Gibbon & Williams, 2002). Eligible participants had to: 1) be a minimum of 18 years of age, 2) Latino/a, 3) report Spanish-language preference, 4) meet MDD criteria, 5) not meet criteria for substance abuse or dependence, bipolar or psychotic disorders, 6) not be receiving psychotherapy, and 7) if taking antidepressants, demonstrate three or more consecutive months of use. Eligible participants completed a baseline assessment to confirm eligibility and attended the first therapy session. Participants were paid $125 throughout the course of the study for completing assessments and for travel.

During a 90-minute baseline appointment, a research assistant reviewed study procedures, obtained verbal informed consent, administered the SCID-IV, and collected demographic/clinical information. Participants were randomized (blocked for gender) to receive 10 weekly sessions of BATD or SC. The BATD Spanish version (Maero et al., unpublished manuscript) used here and in one previous study (Collado et al., 2014) was the translation of the most recent BATD manual (see Lejuez et al., 2011). Active BATD components include daily mood and activity monitoring, activity scheduling, and contracts to elicit others’ assistance to complete activities, if needed. The SC manual used in this study was based on a translation of Novalis, Rojcewicz and Peele (1993) which describes the process of supportive counseling, emphasizes listening empathically, and provides encouragement without providing advice or skills. The manual included three relaxation exercises (See Table 1 for BATD- and SC-specific components). Daily journaling was added to match homework content in BATD. We selected SC as it is consistent with the concept of desahogo, the expectation among LSSP that the goal of therapy is get things off one’s chest and because LSSP tend to attribute depression to a lack of support (e.g., Cabassa, Lester & Zayas, 2007). Both manuals were translated and back-translated by multiple native Spanish-speaker psychologists using established procedures.

Table 1.

Treatment Components by Session

| Session | Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression | Supportive Counseling |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Provide depression psychoeducation Give treatment rationale Introduce daily monitoring Discuss treatment adherence |

Provide depression psychoeducation Give treatment rationale Learn about the client’s depression Discuss treatment adherence Introduce journaling Guide progressive muscle relaxation |

| 2 | Review daily monitoring Discuss the association between mood and activities/behavior Discuss life areas, values, and activities |

Review journaling Engage in an open, client-guided supportive discussion Guide visual imagery relaxation |

| 3 | Review daily monitoring Discuss associations between mood and activities/behavior Assist the client in selecting 15 value-consistent activities Assist the client in activity ranking |

Review journaling Engage in an open, client-guided supportive discussion Guide breathing retraining relaxation |

| 4 | Review daily monitoring Review the client’s activity ranking Assist the client in scheduling value-consistent activities |

Review journaling Engage in an open, client-guided supportive discussion Guide progressive muscle relaxation |

| 5–9 |

Review activities completed by client Assist the client in scheduling value-consistent activities Introduce/discuss contracts |

Review journaling Engage in an open, client-guided supportive discussion Guide client through relaxation exercise |

| 10 | Review activities completed by client Assist client in scheduling activities Review contracts, if needed Discuss relapse prevention |

Review journaling Engage in an open, client-guided supportive discussion Guide progressive muscle relaxation Discuss relapse prevention |

Note. Components specific to each treatment have been italicized.

Therapists and Research Staff

All staff had Spanish language fluency. Research assistants trained in SCID-IV procedures administered the interview at baseline, end-of-treatment, and follow-up and conducted the weekly assessments. Therapists consisted of a post-baccalaureate community therapist, a master’s level graduate student, two advanced graduate students, and three post-baccalaureate students. Therapists self-identified as Latinas (n = 4) and White Americans (n =3). Therapists were randomized across conditions.

Therapy sessions were audiotaped and 20% were rated by a Spanish-speaking research assistant to assess adherence to each treatment with rating checklists developed by [Initials]. BATD therapists demonstrated 96.7% adherence rates and SC therapists demonstrated 97.4% adherence rates. Divergences were discussed in supervision. [Initials] listened to every session and provided feedback to each therapist in the weekly, two-hour supervision meeting. [Initials] met each week for an hour to discuss adherence, fidelity, and competence.

Materials and Measures

Depression

We administered the 21-item Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck, Steer & Brown, 1996) weekly to assess depressive symptoms. The BDI-II Spanish version was evaluated in a sample of 470 Spanish community adults (Sanz, Perdigón & Vázquez, 2003). In the current study, BDI-II internal consistency ranged from .89 – .92 across all sessions. To assess for MDD, we administered the SCID-IV (First et al., 1995) at baseline, end-of-treatment, and follow-up assessments. The SCID-IV has been recommended for use with Latinos (Snipes, 2012, p. 156)

BATD proposed mechanisms of change

The Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale (BADS; Kanter et. al, 2007) measures frequency of activation, escape, and avoidance. To isolate activity levels, we used both the BADS Total Activation scale and the BADS Activation subscale. The subscale included items like “I am content with the amount and types of things I did.” Higher scores indicated greater activation. In the current study, the BADS yielded good internal consistency estimates (α –values ranged from .82 to .89), consistent with extant literature (Barraca, Perez-Alvarez, & Bleda, 2011). The Reward Probability Index (RPI; Carvalho, et al., 2011) is a 20-item scale that measures one’s ability to obtain reinforcement through instrumental behaviors and the presence of aversive or unpleasant experiences in the environment. Internal consistency of the RPI scale was α = .90 in the original validation study. The team that translated BATD into Spanish also translated and back-translated the RPI using established guidelines. Example items included “I make the most of opportunities that are available to me.” Higher scores reflected greater environmental reward. In the current study, the RPI’s Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .82 to .95. Participants completed the BADS and the RPI questionnaires weekly and at the follow-up.

Attitudes toward Treatment

The Therapeutic Alliance with Clinician Questionnaire (TAC; Neale & Rosenheck, 1995) assesses the strength of the therapeutic relationship using a 9-item Likert scale format. The Spanish version of the TAC (Bedregal et al., 2006) was evaluated with depressed individuals and achieved high internal consistency (α = .96). TAC items include “How often are the goals of your work with [therapist] important to you?” Higher scores represent greater alliance. In this study, alpha coefficients ranged from .94 to .97. We developed a satisfaction questionnaire for participants to rate the treatments on a 1 to 6 Likert scale across 9 items including “To what extent has our treatment met your expectations?” Higher scores represented higher treatment satisfaction. Internal consistency ranged from .91 and .96 across sessions. The TAC and the satisfaction questionnaire were administered at sessions 2, 5, 8, 10.

Treatment adherence

We measured adherence by calculating the number of sessions completed, the ratio of homework completed and homework assigned, and latency to attrition.

Data Analytic Plan

We used Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM) analyses to examine within-subject change over time for each of the constructs of interest. HLM permits conduct of intent-to-treat analyses by using all available data without removing participants who dropped out. Chi-square and independent-sample t-test analyses assessed between-group differences in demographic and clinical characteristics. Between-group differences in MDD remission were examined using the Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. A bias corrected Hedge’s g was computed for each effect. Effects were defined as small (0.20–0.49), moderate (0.50–0.79), or large (0.80). We examined attendance differences with Cox proportional hazards survival analyses predicting time to attrition. Independent samples t-test compared differences in homework rates and completed sessions. We examined changes in clinical gains from session 10 to the follow-up using paired t-tests.

Results

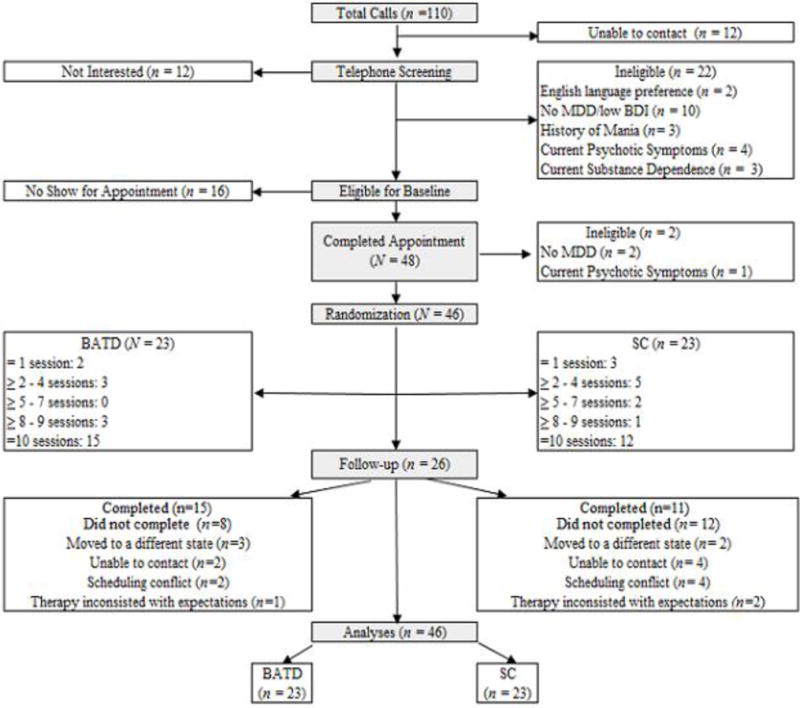

A total of 110 callers contacted [Institution] expressing interest in the study. Forty-six participants were enrolled in treatment. Please see Figure 1 for a Consort Diagram for the study. The sample consisted of 39 females and seven males. The mean age was 35.91 years (SD = 13.80, range =18–74). See Table 2. Two individuals were taking antidepressants. Clinically, 83% of participants met criteria for another disorder besides MDD. See Table 3. Mean BDI score was 29.70 (SD = 10.36), indicating severe depression. There were no between-group differences in either demographic or clinical characteristics (p-values ≥ 0.20).

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flowchart of study participants, randomization, treatment, follow-ups, and inclusion analyses. BATD: Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression; SC: Supportive Counseling; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; BDI: Beck Depression Inventory.

Table 2.

Comparisons of Baseline Demographic Characteristics Across Treatment Conditions

| Demographic Characteristic | Overall Sample

|

BATD

|

SC

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | % | M | SD | % | M | SD | % | p | |

| Age | 35.91 | 13.80 | 33.74 | 12.25 | 38.18 | 15.20 | 0.29 | |||

| Gender (female) | 85 | 83 | 87 | 0.68 | ||||||

| Education (grade) | 10.93 | 3.74 | 11.45 | 3.71 | 10.38 | 3.78 | 0.35 | |||

| Years in the U.S. | 12.09 | 8.64 | 11.41 | 8.10 | 12.77 | 9.29 | 0.61 | |||

| Total Annual Income | 0.44 | |||||||||

| ≤$14,999 | 46 | 45 | 47 | |||||||

| $15,000–$29,999 | 27 | 20 | 35 | |||||||

| $30,000–$44,999 | 22 | 25 | 18 | |||||||

| $45,000–$59, 999 | 5 | 10 | 0 | |||||||

| Employment Status | 0.62 | |||||||||

| Employed half-time | 11 | 9 | 14 | |||||||

| Employed full-time | 41 | 48 | 35 | |||||||

| Marital Status | 0.91 | |||||||||

| Single/never married | 40 | 44 | 35 | |||||||

| Married | 30 | 40 | 30 | |||||||

| Divorced | 14 | 13 | 15 | |||||||

| Other | 16 | 13 | 20 | |||||||

| Immigration Status | 0.34 | |||||||||

| Permanent Resident | 22 | 18 | 27 | |||||||

| Undocumented | 41 | 36 | 50 | |||||||

| Citizen | 17 | 23 | 13 | |||||||

| Other | 16 | 23 | 10 | |||||||

| Immediate Family in the U.S. (yes) | 89 | 86 | 91 | 0.60 | ||||||

| Able to Understand Spoken English | 0.34 | |||||||||

| Yes | 22 | 30 | 13 | |||||||

| No | 13 | 13 | 13 | |||||||

| A little | 65 | 57 | 74 | |||||||

| Able to Understand Written English | 0.43 | |||||||||

| Yes | 28 | 35 | 22 | |||||||

| No | 20 | 13 | 26 | |||||||

| A little | 52 | 52 | 52 | |||||||

| Country of Origin | 0.29 | |||||||||

| El Salvador | 28.3 | 21.7 | 34.8 | |||||||

| Guatemala | 15.2 | 17.4 | 13.0 | |||||||

| Honduras | 13.0 | 17.4 | 8.7 | |||||||

| Mexico | 13.0 | 8.7 | 17.4 | |||||||

| Colombia | 8.7 | 8.7 | 8.7 | |||||||

| Peru | 4.3 | 8.7 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Chile | 4.3 | 0.0 | 8.7 | |||||||

| Nicaragua | 2.2 | 4.3 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Paraguay | 2.2 | 4.3 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Dominical Republic | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | |||||||

| Costa Rica | 2.2 | 4.3 | 0.0 | |||||||

| Ecuador | 2.2 | 0.0 | 4.3 | |||||||

Note. BATD = Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression. SC = Supportive Counseling

Table 3.

Comparisons of Baseline Clinical Characteristics Variables Across Treatment Conditions

| Clinical Characteristic | Overall Sample | BATD | SC | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSM-IV-TR Psychiatric Diagnosis (%) | ||||

| Dysthymia | 43.50 | 39.10 | 47.80 | 0.55 |

| Panic Disorder | 23.90 | 21.70 | 26.10 | 0.73 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 28.30 | 34.80 | 21.70 | 0.33 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 65.20 | 73.90 | 56.50 | 0.22 |

| Ever received treatment for depression (yes %) | 28.30 | 36.40 | 21.70 | 0.28 |

Note. BATD: Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression; SC: Supportive Counseling; DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic Statistical Manual, 4th Edition- Text Revised

We controlled for education in models containing depressive symptoms as a result of their positive association over time (p = 0.01). We also controlled for therapist assignment given the range in therapists’ education and training. No other covariates were identified.

Primary Outcomes

Depression

Depressive symptoms decreased over time (β = −2.16, SE = 0.21, p < 0.001). The interaction between condition and time was significant (β = −0.59, SE = 0.28, p = 0.04), indicating greater reductions in depressive symptoms for BATD participants relative to those assigned to SC. Among treatment completers, participants assigned to BATD (93.3% of n =15) showed greater MDD remission rates [χ2 (1) = 6.52, p = 0.01] than those in SC (50% of n=12).

BATD proposed mechanisms of change

BADS Total Activation scores showed increases over time (β = 3.88, SE = 0.61, p < 0.001) but no interaction between condition and time (β = 0.67, SE = 0.82, p = 0.41), suggesting no between-group differences. The BADS Activation subscale scores also increased over time (β = 0.61, SE = 0.25, p = 0.02). The interaction between condition and time was significant (β = 0.83, SE = 0.28, p = 0.01), such that those in BATD reported a greater increase in activity level over time relative to those in SC. RPI Environmental Reward scores increased over time (β = 0.79, SE = 0.16, p < 0.001). The interaction of condition and time was significant (β = 0.46, SE = 0.23, p = 0.05), indicating that BATD participants showed greater increases in RPI over time relative to SC participants.

Effect Sizes

Table 4 displays possible scores for each scale, mean scores of clinical variables at baseline, end-of-treatment, and follow-up, along with the respective effect sizes. Effect sizes were large for the BADS Activation subscale and small for the other study variables.

Table 4.

Means and Standard Deviations of Baseline, End-of-Treatment, and One-Month Follow-Up Outcomes by Group

| Clinical Variable | Baseline (N = 46) | End-of-treatment (N = 27) | Follow-up (N = 26) | Bias Corrected Hedge’s g Effect Size (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDI (range 0 – 63) | −0.44 (−1.23, 0.35) | |||

| BATD | 29.87 (9.26) | 9.41 (6.74) | 9.58 (8.14) | |

| SC | 29.52 (11.56) | 12.02 (6.92) | 13.50 (9.30) | |

| BADS (range 0–150) | −0.13 (−0.91, 0.65) | |||

| BATD | 49.52 (17.99) | 89.14 (19.70) | 87.57 (18.23) | |

| SC | 58.74 (28.41) | 88.38 (20.69) | 90.50 (26.39) | |

| BADS-Activation Subscale (range 0 – 35) | 0.90 (0.08, 1.71) | |||

| BATD | 19.17 (7.62) | 31.00 (7.43) | 31.14 (6.89) | |

| SC | 21.39 (11.70) | 25.08 (11.88) | 24.13 (8.43) | |

| RPI (range 0 – 80) | 0.29 (−0.49, 1.08) | |||

| BATD | 48.22 (7.52) | 54.80 (9.52) | 54.14 (8.11) | |

| SC | 46.86 (10.14) | 51.58 (6.57) | 51.88 (6.33) |

Note. BDI: Beck Depression Inventory; BATD: Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression; SC: Supportive Counseling; BADS: Behavioral Activation Depression Scale; RPI: Reward Probability Index.

Treatment Adherence

Sessions completed

Participants completed an average of 7.35 (SD = 3.65) sessions and completed sessions did not differ between conditions (p = 0.26). Eighteen individuals in BATD (78%) and 13 participants in SC (57%) completed at least 8 of 10 sessions. Time to attrition: Attrition was similar for BATD and SC after adjusting for baseline depressive symptoms and therapist assignment [χ2 (11) = 14.65, p = 0.20]. No other variables related to attrition (p-values ≥ 0.31). Homework completion: Among participants who completed more than one session (N= 40; 87%), homework completion for BATD was 75.18% and 63.35% for SC, and not significantly different after statistically controlling for completed sessions [F (1, 37) = 1.63; p = 0.21].

Secondary Analyses - Treatment Satisfaction and Therapeutic Alliance

Treatment satisfaction and therapeutic alliance increased over time (β = 0.59, SE = 0.18, p = 0.002 and β = 1.02, SE = 0.19, p < 0.001, respectively) but did not differ by condition (p = 0.17 and p = 0.91, respectively).

Maintenance of Clinical Gains over a One-Month Follow-up

Fifteen people randomized to BATD (65%) and 11 to SC (48%) completed the one-month follow-up. HLM analyses including the follow-up showed that statistical significance remained similar to the end-of-treatment results: there was a condition by time interaction for depressive symptoms (β = −0.55, SE = 0.24, p = 0.03), which indicates that BATD participants showed greater decreases in depression relative to SC participants. A condition by time interaction was also observed in activity level measured by the BADS-Activation subscale (β = 0.93, SE = 0.32, p = 0.01), and environmental reward (β = 0.47, SE = 0.23, p = 0.05), such that BATD participants showed steeper increases in these constructs relative to SC participants. We also conducted paired t-tests between the end-of-treatment and the one-month follow-up and confirmed that there were no statistically significant changes (all p-values > 0.16) between the two assessment time-points. MDD remission rates remained consistent between end-of-treatment and the follow-up.

Discussion

Compared to SC, BATD led to greater reductions in depressive symptoms and higher MDD remission rates. Additionally, BATD led to more increases in environmental reward indexed by the RPI and activity level measured by the BADS Activation subscale. Study findings did not support the hypothesis that BATD participants would report higher treatment satisfaction, therapeutic alliance, and treatment adherence. In terms of BATD adherence, 78% of individuals completed at least eight of the 10 sessions, which demonstrates its potential value as an empirically-supported depression that is able to support adherence among LSSP. Finally, clinical gains were sustained in SC and BATD from the last session to the follow-up.

Overall, these results compare favorably to extant depression treatment research with LSSP (e.g., Kanter et al., 2014) and support BATD’s efficacy for depressed LSSP in comparison to a credible control condition. Importantly, the findings also provide evidence that the changes observed are due to BATD and not to non-specific treatment variables. Two secondary findings are worthy of consideration. First, similar adherence in both conditions, while not hypothesized, may mitigate concerns about investigator bias toward BATD. Second, while greater activation was found for the BADS activation subscale, no group differences were found for the total scale. Changes in the subscale but not in the total scale may reflect that domains measured by the total scale (i.e., Avoidance/Rumination) are not as directly relevant for BATD, which is more focused on helping clients to increase their valued daily activities.

Several study limitations are evident including: a) a small sample size that prevented testing the temporal relationships of BATD mechanisms of change; b) high comorbidity that limits the generalizability of these results; c) the use of assessments translated but not extensively validated among LSSP (i.e., RPI and BADS); d) the absence of an empirically-supported treatment for depression as a control group; and e) a short follow-up period.

Despite these limitations, the present study provides important evidence for BATD’s efficacy in treating depressed LSSP, a historically underserved and underrepresented U.S. population in clinical and research settings. Rooted in strong behavioral theories, BATD has various strengths that will facilitate its implementation and dissemination in real-world community settings such as its brevity, cultural-responsiveness, ability for personalized mental health care delivery, and ease of implementation by novice therapists. As a result, future research is warranted to evaluate the transportability and generalizability of BATD in an effectiveness trial.

Public Health Significance Statement.

The current study demonstrates support for using Behavioral Activation Treatment for Depression (BATD) to decrease depression and increase activity level and environmental reward among Latinos who prefer to speak Spanish. The findings add to the growing depression treatment literature in this underserved U.S. ethnic minority group.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported in part by the National Institute of Mental Health F31MH098512-02 awarded to Anahi Collado. The authors would like to acknowledge all of those who worked on P.A.Z including Emily Blevins, Laura Sirbu, Katherine Long, Fernanda Oliveira, Christina Buckley, Claudia Choque, Alexandra Olson, and Maritze Ortega.

Footnotes

As outlined in Collado and colleagues (2014), there are several reasons we chose to test BATD for depressed LSSP. BATD is grounded in strong behavioral theory. BATD consists of fewer sessions and modules than other BA approaches and most psychosocial treatment protocols, while leading to clinically-significant reductions in depression. Further, BATD’s goal is for clients to closely examine their personal values and schedule activities that are value-consistent in an idiographic format. The idiographic nature of BATD holds notable relevance to LSSP populations for the following reasons; LSSP represent a heterogeneous population with diverse sociocultural contexts and histories. BATD maintains cultural sensitivity by tailoring treatment to each client without the use of global, cultural modifications to core treatment components. Consistent with current multicultural approaches, BATD allows the integration of salient aspects of each client’s multidimensional identity into therapeutic goals and procures detachment from cultural stereotypes. Finally, BATD accommodates the needs of low-literacy clients through modified treatment materials.

Contributor Information

Anahí Collado, Emory University – School of Medicine.

Marilyn Calderón, Latin American Youth Center/Maryland Multicultural Youth Centers.

Laura MacPherson, Univeristy of Maryland-College Park.

Carl Lejuez, Univeristy of Maryland-College Park.

References

- Barraca J, Pérez-Álvarez M, Bleda JHL. Avoidance and activation as keys to depression: Adaptation of the Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale in a Spanish sample. The Spanish journal of psychology. 2011;14:998–1009. doi: 10.5209/rev_sjop.2011.v14.n2.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. 2nd. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bedregal L, Paris M, Añez L, Shahar G, Davidson L. Preliminary Evaluation of the Validity and Reliability of the Spanish Version of the Therapeutic Alliance with Clinician (TAC) Questionnaire. Social Indicators Research. 2006;78:19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Patel SR, Liu L, Jiang H, Lewis-Fernández R, Schmidt AB, et al. National trends in ethnic disparities in mental health care. Medical Care. 2007;45(11):1012–1019. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180ca95d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Lester R, Zayas LH. ‘It’s like being in a labyrinth:’ Hispanic immigrants’ perceptions of depression and attitudes toward treatments. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2007;9:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho JP, Gawrysiak MJ, Hellmuth JC, McNulty JK, Magidson JF, Lejuez CW, Hopko DR. The Reward Probability Index (RPI): Design and validation of a scale measuring access to environmental reward. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado A, Castillo SD, Maero F, Lejuez CW, MacPherson L. Pilot of the brief behavioral activation treatment for depression in Latinos with limited English proficiency: preliminary evaluation of efficacy and acceptability. Behavior therapy. 2014;45:102–115. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferster CB. A functional analysis of depression. American Psychologist. 1973;28:857–870. doi: 10.1037/h0035605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RR, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institutes; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter JW, Santiago-Rivera AL, Santos MM, Nagy G, López M, Hurtado GD, West P. A Randomized Hybrid Efficacy and Effectiveness Trial of Behavioral Activation for Latinos with Depression. Behavior Therapy. 2014;46:177–192. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanter JW, Mulick PS, Busch AM, Berlin KS, Martell CR. The Behavioral Activation for Depression Scale (BADS): Psychometric properties and factor structure. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2007;29:191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Keyes KM, Martin SS, Hatzenbuehler ML, Blanco C, Bates LM, Hasin DS. Mental health service utilization for psychiatric disorders among Latinos living in the United States: the role of ethnic subgroup, ethnic identity, and language/social preferences. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:383–94. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0323-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejuez CW, Hopko DR, Acierno R, Daughters SB, Pagoto SL. Ten year revision of the brief behavioral activation treatment for depression: revised treatment manual. Behavior Modification. 2011;35:111–161. doi: 10.1177/0145445510390929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maero F, Mathot MI, Principi C. Manual revisado para Tratamiento Breve de Activación Conductual para Depresión (BATD-R) (unpublished manual) [Google Scholar]

- Magidson JF, Gorka SM, MacPherson L, Hopko DR, Blanco C, Lejuez CW, Daughters SB. Examining the effect of the Life Enhancement Treatment for Substance Use (LETS ACT) on residential substance abuse treatment retention. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:615–623. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neale MS, Rosenheck RA. Therapeutic alliance and outcome in a VA intensive case management program. Psychiatric Services. 1995;46:719–721. doi: 10.1176/ps.46.7.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novalis P, Rojcewicz S, Peele R. Clinical Manual of Supportive Psychotherapy. American Psychiatric Association; Arlington, VA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Rivera A, Kanter J, Benson G, Derose T, Illes R, Reyes W. Behavioral activation as an alternative treatment approach for Latinos with depression. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2008;45:173–185. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.45.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz J, Perdigón A, Vázquez C. Adaptación española del Inventario para la Depresión de Beck-ll (BDI-II): 2. Propiedades psicométricas en población general. Cliníca y Salud. 2003;14(3):249–280. [Google Scholar]

- Snipes C. Assessment of Anxiety with Hispanics (2012) In: Benuto LT, editor. Guide to psychological assessment with Hispanics. New York: Springer Science & Business Media; 2012. pp. 153–162. (2012) [Google Scholar]

- Sturmey P. Behavioral activation is an evidence-based treatment for depression. Behavior Modification. 2009;33:818–829. doi: 10.1177/0145445509350094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]