Abstract

Polyethylene glycol (PEG) surface modification is one of the most widely used approaches to improve the solubility of inorganic nanoparticles, prevent their aggregation and prolong their in vivo blood circulation half-life. Herein, we developed double-PEGylated biocompatible reduced graphene oxide nanosheets anchored with iron oxide nanoparticles (RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG). The nanoconjugates exhibited prolonged blood circulation half-life (~27.7 h) and remarkable tumor accumulation (>11 %ID/g) via enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. Due to strong near-infrared absorbance and superparamagnetism of RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG, multimodality imaging combining positron emission tomography imaging (PET) with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and photoacoustic (PA) imaging was successfully achieved. The promising results suggest great potential of these nanoconjugates for multi-dimensional and more accurate tumor diagnosis and therapy in the future.

Keywords: Reduced graphene oxide, Iron oxide nanoparticles, Positron emission tomography, PEGylation, Magnetic resonance imaging, Photoacoustic imaging

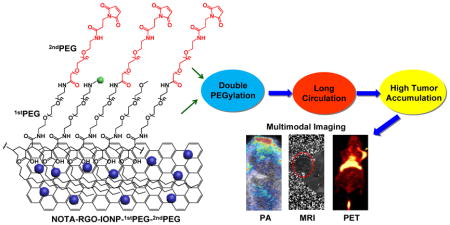

Graphical Abstract

Double PEGylated reduced graphene oxide nanosheets anchored with iron oxide nanoparticles exhibited ultra-long blood circulation half-life and remarkably high tumor accumulation, which could be utilized as a multimodality imaging nanoprobe for combined PET, MRI and photoacoustic imaging.

1. Introduction

Inorganic nanoparticle-based contrast agents with strong signal output and multifunctionality have shown great potential for efficient tumor diagnosis and therapy.1, 2 However, inorganic nanoparticles are generally insoluble and easy to aggregate in physiological environment, severely limiting their applications to in vivo tumor targeting.3, 4 To overcome this limitation, conjugating biocompatible polymers (e.g. polyethylene glycol (PEG)) onto nanoparticles is one of the most commonly used methods.5–7 The PEG chains can effectively improve the solubility and prevent aggregation of nanoparticles by passivating their surface and diminishing their association with serum and opsonin.8–10 Of note, as reported in our previous work, enhanced stability of nanoparticles was achieved by decorating two types of PEG chains in comparison to a single type or non-PEGylated nanoparticles.11 Furthermore, optimizing the PEGylation of nanoparticles can also prolong their circulation time in blood and reduce the uptake by reticuloendothelial system (RES), in which NPs are rapidly shuttled out of circulation to liver, spleen or bone marrow.3, 12 Numerous studies have reported that denser PEG coating and larger PEG chains will result in longer circulation time in vivo,13 which allows nanoparticles to continuously pass through tumor vasculature and passively accumulate in tumor sites at a higher concentration than the healthy tissue due to enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect.14–16

Reduced graphene oxide (RGO) nanosheets with high near-infrared (NIR) light absorbance and biocompatibility have recently been applied in hyperthermia tumor therapy,17–19 drug delivery20–22 and bioimaging.23, 24 Our previously works have demonstrated that antibody conjugated radiolabeled RGO conjugate can specifically target tumor vasculature and promptly detected by positron emission tomography (PET) imaging.25 With high sensitivity and providing clear visualization of solid tumor and quantitative information, PET imaging is an excellent technique for diagnosing and determining the stages of many types of tumor.26 However, PET imaging fails to convey anatomical information and detect early lesions due to the limited spatial resolution.27 In contrast, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers excellent soft-tissue contrast with higher resolution.28 In addition, RGO-based nanomaterial exhibited high NIR absorbance, which can be employed as a strong photoacoustic (PA) imaging contrast agent with high spatial resolution (up to 50–500 μm) and deep tissue penetration (up to 5 cm).29, 30 By combining PET imaging with MRI and PA imaging as an integrated imaging system, the high-order multimodalality imaging (PET/MRI/PA) can overcome the limitations of each modality independently and result in obtaining higher quality and more useful data.31 More importantly, since PA imaging and MRI display the real biodistribution of nanoparticles in tumor site rather than the distribution of the isotopes, multimodality imaging (PET/MRI/PA) can better render the in vivo fate of nanoparticles and provide more accurate diagnosis and prognosis in future applications.32–36

In this work, we developed a novel multifunctional nanocomposite by decorating reduced graphene oxide nanosheets with iron oxide magnetic nanoparticles (RGO-IONP) and coating two types of PEG chains to achieve a long-circulating multimodality imaging probe. Upon optimal surface modification, the in vivo blood circulation half-life and passive tumor targeting efficacy were highly improved. Three different imaging modalities (PET/MR/PA) were subsequently conducted, which revealed multi-aspect and more precise information of tumors.

2. Experimental

2.1 Reagents and materials

All reagents were of analytical or higher grade. S-2-(4-Isothiocyanatobenzyl)-1,4,7- triazacyclononane-1,4,7-triacetic acid (p-SCN-Bn-NOTA) was purchased from Macrocyclics, Inc. (Dallas, TX). Succinimidyl carboxymethyl PEG maleimide (SCM-PEG-Mal; molecular weight: 5 kDa) was purchased from Creative PEGworks (Winston Salem, NC). Chelex 100 resin (50–100 mesh) was purchased from SigmaeAldrich (St. Louis, MO). Water and all buffers were of Millipore grade and pre-treated with Chelex 100 resin to ensure that the aqueous solution was free of heavy metal. All other reaction chemicals and buffers were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Fair Lawn, NJ).

2.2 Characterization

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained by using Tecnai TF-30, 300kv field emission TEM. Size analysis was performed on Nano-ZS90 Zetasizer (Malvern Instruments Ltd.). Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectrum was performed by Equinox 55/S FT-IR/NIR spectrophotometer. The iron concentration in solution was measured by Microwave Plasma - Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (MP-AES).

2.3 Syntheses of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG and NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG nanocomposite

RGO-IONP nanoparticles prepared from graphene oxide and iron chloride hexahydrate via a hydrothermal reaction according to our previous protocol.30, 37 In brief, GO was produced by modified Hammers method. 0.1 g GO was then dissolved in 20 ml ethylene glycol/diethylene glycol solution (ethylene glycol: diethylene glycol= 1:19, by volume). 1.5 g of sodium acrylate, 1.5 g of sodium acetate and 0.54 g of FeCl3·6H2O were added into GO solution and then transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave and sealed before heating at 200 °C for 10h. The resulting RGO-IONP was washed by ethanol and water for several times.

The first PEG, C18PMH-PEG5000-NH2 (poly (maleic anhydride-alt-1-octadecene-)-PEG5000-NH2), was modified on RGO-IONP by hydrophobic interactions between C18PMH chain and RGO as reported by our previous study.9, 38 The obtained RGO-IONP-1stPEG were purified by centrifugation with 300 kDa MWCO filters at 4500 rpm for 6 min (repeated 7 times) to further remove free PEG. Then p-SCN-Bn-NOTA was added to RGO-IONP-1stPEG at a molar ratio of 10:1 at pH 9.0 for 24 h, where the chemical reaction happened between SCN groups and NH2 groups. The resulting NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG was purified by size exclusion column chromatography 10k using PBS as the mobile phase. Most NH2 groups were still present on the surface of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG for further functionalization. Subsequently, NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG was reacted with SCM-PEG5000-Mal 2ndPEG at a molar ratio of 1:200 at pH 8.5 for 2 h to form a stable amide bond, based on the reaction between the amino group at the end of the 1stPEG and NHS ester at the end of the 2ndPEG. The resulting of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG was purified by centrifugation with 100 kDa MWCO Amicon filters at 9500 rpm for 10 min (repeated 5 times).

2.4 Cell lines and animal model

4T1 murine breast cancer was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and cultured as previously described.25 Cells were used for in vivo experiments when they reached ~80% confluence. All animal studies were conducted under a protocol approved by the University of Wisconsin Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Four or five weeks old female BALB/c mice (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) were injected with 2×106 4T1 cells in the shoulder (for PET and PA imaging) or flank (for MR imaging) to generate the 4T1 breast cancer model. The BALB/c mice were used for in vivo experiments when the tumor diameter reached 6–8 mm.

2.5 64Cu-labeling, in vivo blood circulation test and serum stability

64Cu was produced with an onsite cyclotron (GE PETtrace). 64CuCl2 (74 MBq) was diluted in 0.3 mL of 0.1 M sodium acetate buffer (pH 5.0) and mixed with 0.2 mg of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG or NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG. The reaction was conducted at 37 °C for 30 min with constant shaking, then 5 μL 0.1 M EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) was added into the solution and shakes another 5 min to remove non-specific bound 64Cu. The resulting 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG or 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG was purified by PD-10 size exclusion column chromatography using PBS as the mobile phase. The radioactive fractions were collected for further in vitro and in vivo studies. Blood circulation tests were carried out on ICR mice. Mouse blood (40~50 μL) was directly collected from the orbital sinus at different time point and measured by gamma counter immediately.

Serum stability studies were carried out to ensure that 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG or 64Cu-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG was sufficiently stable for in vivo applications. 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG or 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG was incubated in 50% mouse serum at 37 °C for up to 48 h. Portions of the mixture were sampled at different time points and filtered through 300 kDa MWCO filters. The radioactivity within the filtrate was measured, and the percentages of retained (i.e., intact) 64Cu on the 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG or 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG conjugates were calculated using the equation:

2.6 PET imaging and biodistribution study

PET scans of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (6 mice per group), at various time points post-injection of 5–8 MBq of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG or 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG via tail vein, were performed using a microPET/microCT Inveon rodent model scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions USA, Inc.). Detailed procedures for data acquisition, image reconstruction, and region-of-interest (ROI) analysis of the PET data have been reported previously23, 25. Quantitative PET data of the 4T1 tumor and major organs were presented as percentage injected dose per gram of tissue (%ID/g).

To validate that the ROI values based on PET imaging accurately reflected the radioactivity distribution in tumor-bearing mice, ex vivo biodistribution studies were conducted at 48 h post-injection (p.i.). After euthanizing the mice, blood, 4T1 tumor, and major organs/tissues were collected and wet-weighed. The radioactivity in the tissue or blood was measured using a gamma counter (PerkinElmer) and presented as %ID/g (mean ± SD).

2.7 MRI and PA imaging

In vivo T2-mapped MR imaging was performed at 3 h and 24 h post-injection after intravenously injection of 400 μL NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG with the Fe concentration of 5.2 mM using a 4.7 T small animal scanner (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Here are the parameters for T2-mapped MR imaging: Spin Echo Multi-Slice sequence, TR = 1000 ms, TE = 13.8, 18.8, 23.8, 28.8, 33.8, 38.8, 43.8, 48.8, 53.8 and 58.8 ms, Averages = 1, Dummy scans = 4, Matrix size = 128 x 128. The transverse relaxivity (r2) of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG was measured to be 76.1 mM−1s−1. PA imaging was performed on Vevo LAZR Photoacoustic Imaging System (VisualSonics, Inc., Toronto, Canada) with a laser excitation wavelength of 808 nm and a focal depth of 100 mm. 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were intravenously injected with NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (150 μL, 0.3 mg/ml) and scanned at 24 h post-injection. The same volumes of PBS were injected in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice as control groups.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis and Characterizations

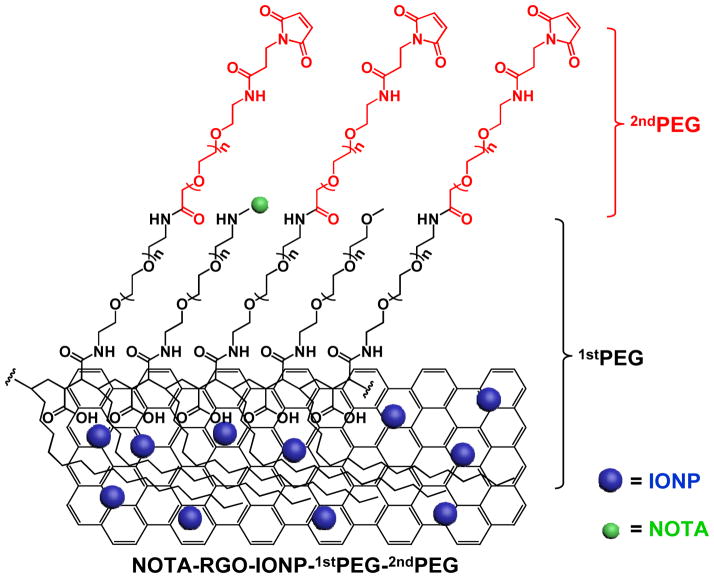

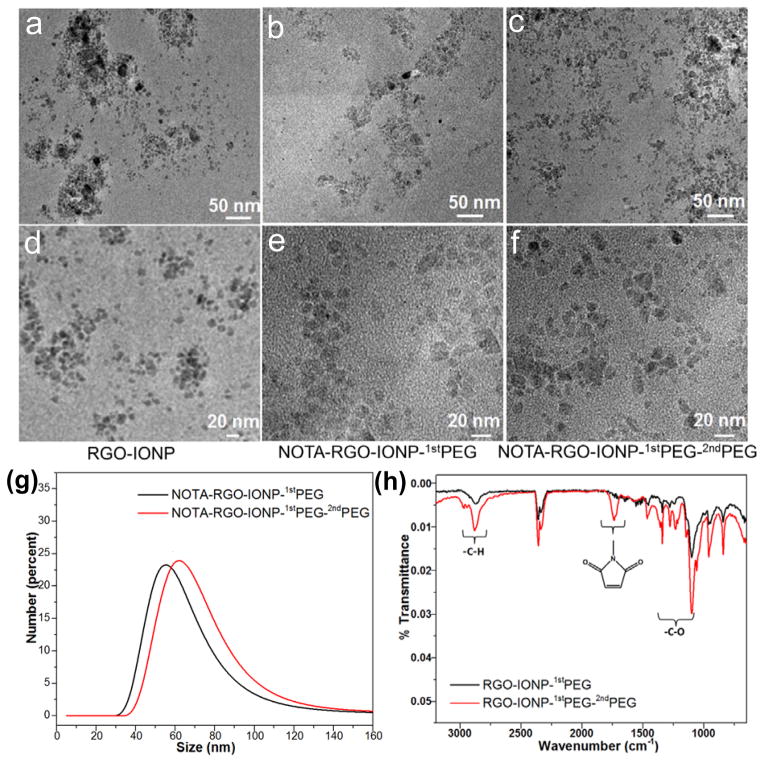

The schematic structure of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG nanocomposite was shown in Figure 1. Through hydrophobic interaction between C18PMH chain and RGO, 1stPEG was stably attached on the surface of RGO-IONP, which effectively prevented the possible aggregation and provided amino groups for further surface modification. NOTA and 2ndPEG (Mal-PEG5k-SCM) were then covalently reacted with the amino groups for chelating radioisotopes and enhancing blood circulation half-life, respectively. The morphology and structure of RGO-IONP, NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG and NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG were elucidated by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) measurement, as shown in Figure 2a–f. Iron oxide nanoparticles (6–8 nm) were evenly distributed on the surface of RGO nanosheets (15–20 nm; Figure 2a and 2d). After surface modification with 1stPEG and 2ndPEG, the morphologies of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG and NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG were almost unchanged (Figure 2c and 2f). The hydrodynamic sizes of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG and NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG nanocomposite were then investigated by the dynamic light scattering (DLS). As shown in Figure 2g, the average size of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG was about 63.8 ± 4.5 nm in PBS solution, while the average size increased to 71.6 ± 3.8 nm after conjugating with 2ndPEG. The sizes measured by DLS were much larger than those by TEM, because TEM solely displayed the morphology of RGO-IONP cores without showing PEG coating.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the structure of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG nanocomposite.

Figure 2.

TEM images of RGO-IONP (a and d), NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG (b and e) and NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (c and f). (g) Size analysis of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG (black line) and NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (red line) by DLS. (h) The FT-IR spectrum of RGO-IONP-1stPEG (black line) and RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (red line).

The presence of functional groups on RGO-IONP-1stPEG and RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG nanocomposites were studied by Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy (Figure 2h), in which the C-H stretch (~2800 cm−1) and C-O stretch (1100~1500 cm−1) peaks were much stronger on RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG than those on RGO-IONP-1stPEG at the same concentration. In addition, the observed peaks of maleimide groups (1700 cm−1)39 on RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG clearly demonstrated the successful conjugation of 2ndPEG to RGO-IONP-1stPEG, since the maleimide groups were only present on 2ndPEG.

3.2 In vivo blood circulation half-life and serum stability

In vivo blood circulation time of nanoprobes or nanoplatforms is highly correlated with the targeting efficiency in leaky tumor model,16 since the extravasation of nanoparticles from tumor vasculature to extracellular microenvironment is an accumulative process. Higher nanoparticles concentration in blood and longer blood elimination half-life are favorable to improve tumor targeting efficiency through enhanced EPR effect.40 Conjugating another PEG chains on the surface of RGO-IONP-1stPEG could further reduce the contact with proteins and small molecules in blood and improve circulation time, therefore providing sufficient time for RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2stPEG to not only reach the tumor site but also remained at high concentration for in vivo signal acquisition.

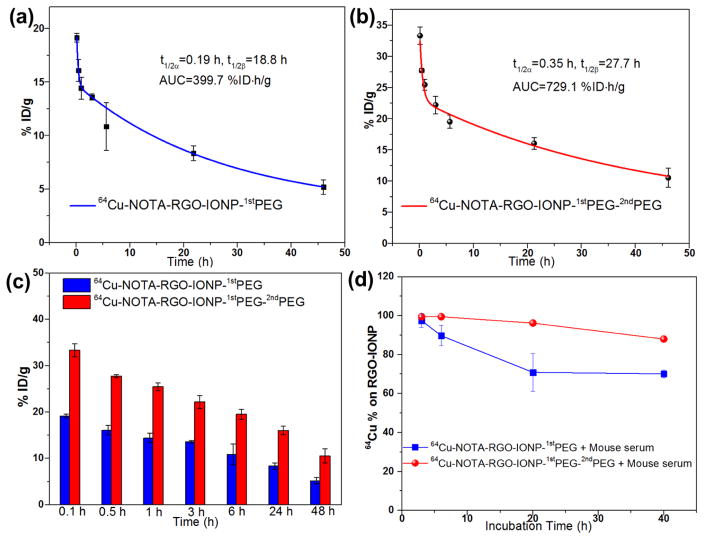

The pharmacokinetics of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG and 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG was observed as a two-compartment model with distribution half-life (t1/2α) and elimination half-life (t1/2β) after intravenous injection (Figure 3a and 3b), where the short distribution half-life (t1/2α) represents rapid access to each tissue including the tumor region immediately after intravenous injection of the nanoparticles, and the long elimination half-life (t1/2β) accounts for slow clearance of the nanoparticles from the blood circulation.13 During the period 0–48 h post-injection, t1/2α of 0.19 h and t1/2β of 18.8 h were calculated in 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP coated with only one type of PEG (Figure 3a), which were basically consistent with our previous study.30 Whereas after conjugating with 2ndPEG, the distribution half-life and elimination half-life were remarkably increased to 0.35 h and 27.7 h, respectively (Figure 3b). The uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG in blood was 5.2% at 48 h p.i., while the uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG was 10.5% at the same time point (Figure 3c). The overall area under the curve (AUC) of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG was 1.8-fold larger than that of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG, indicating the significant enhancement in blood circulation half-live after simultaneously coating two types PEG.

Figure 3.

Blood circulation tests of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG (a) and 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (b), fitting by two-compartment model with distribution half-life (t1/2α) and elimination half-life (t1/2β). AUC = areas under curve. (c) Histogram of blood concentration of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG (blue) and 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (red) at different time points from (a) and (b). (d) Serum stability studies of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG (blue) and 64Cu-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (red). All data represent 3 mice/times per group.

Serum stability studies of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG and 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG were subsequently conducted to validate the stability of 64Cu labeling in vitro and the feasibility for in vivo applications (Figure 3d). After incubating with mouse serum at 37 °C for 40 h, nearly 90% 64Cu still remained intact on NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG. In contrast, 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG was not as stable and lost 30% 64Cu in first 20 hours. Similar results were observed from our previous studies as well.34 The difference of the serum stability between 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG and 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG was believed due to the protecting function of 2ndPEG. With only one time PEGylation, NOTA and 64Cu that were exposed on the surface of nanoparticles directly interacted with the serum proteins, resulting in detachment and excretion through urinary and bile-to-feces pathways in a very short time. The possible detachment of NOTA and 64Cu was significantly reduced after coating 2ndPEG. It also explained why the blood concentrations of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG were higher than that of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG at all the tested time points. Since PET imaging detected isotope rather than nanoparticles per se, high radio-stability in serum made 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG more preferable for in vivo imaging and truly reflects the distribution of nanoparticles.

3.3 PET imaging and biodistribution studies

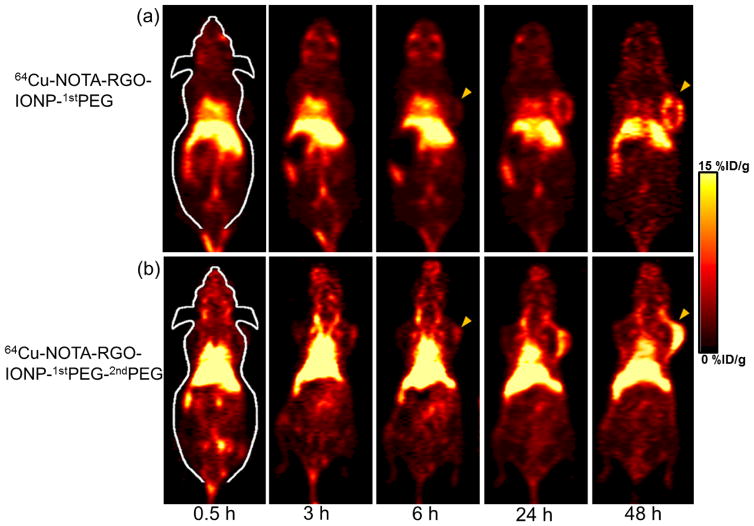

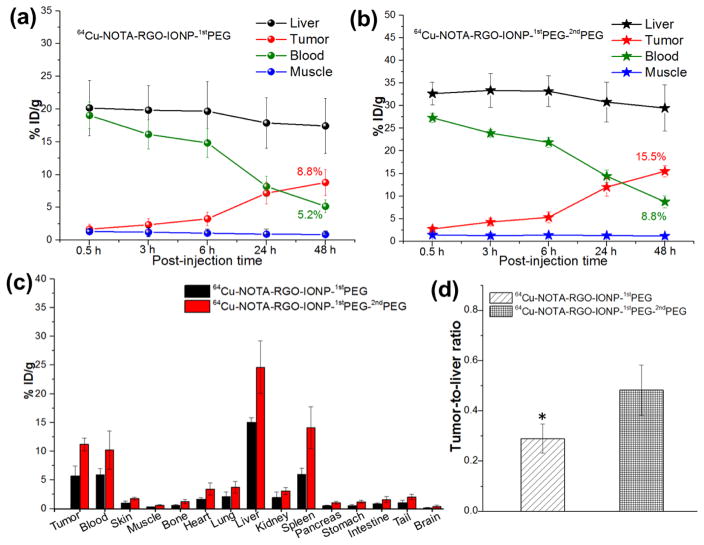

In the consideration of the enhanced blood circulation half-life of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG, time points of 0.5 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h and 48 h p.i. were chosen for serial PET scans in 4T1 tumor-bearing mice. The PET images of post-injection of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG and 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG at different time point were shown in Figure 4a and 4b respectively. And quantitative data which obtained from region-of-interest (ROI) analysis of PET data were shown in Figure 5a and 5b.

Figure 4.

Serial coronal PET images of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice at different time point post-injection of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG (a) and 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (b). Tumors were indicated by yellow arrowheads.

Figure 5.

Quantitative region-of-interest (ROI) analysis of the PET data. (a) Time-radioactivity uptake curves of liver, 4T1 tumor, blood and muscle after intravenous injection of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG. (b) Time- radioactivity uptake curves of liver, 4T1 tumor, blood and muscle after intravenous injection of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG. (c) Biodistribution studies in 4T1 tumor bearing mice at 44 h post-injection of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG (black) and 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (red). (d) Tumor-to-liver ratio of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG (left) and 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (right) based on biodistribution study. The difference between two groups was significant (p value < 0.05). All data represent 6 mice per group.

Since the hydrodynamic diameter of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG and 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG were above the cutoff for renal filtration (~ 5 nm), the main clearance was through hepatobiliary pathway. The liver uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG were 32.7 ± 2.5, 33.4 ± 3.7, 33.2 ± 3.4, 30.8 ± 4.4, 29.5 ±5.1 %ID/g at 0.5 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h p.i. respectively, while the liver uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG were lower (20.2 ± 4.2, 19.8 ± 3.7, 19.7 ± 4.6, 17.9 ± 3.9, 17.4 ± 4.2 %ID/g at 0.5 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h p.i. respectively), possibly due to the lower radio-stability. Both nanocomposites slowly accumulated in the tumor and were clearly visible at 24 h (Figure 4a and 4b). However, the tumor uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (2.8 ± 0.5, 4.3 ± 0.8, 5.3 ± 1.2, 12.0 ± 2.0, 15.5 ±1.2 %ID/g at 0.5 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h p.i. respectively) were significantly higher than that of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG (1.6 ± 0.7, 2.4 ± 0.9, 3.3 ± 1.0, 7.2 ± 1.7, 8.8 ±2.0 %ID/g at 0.5 h, 3 h, 6 h, 24 h, 48 h p.i. respectively), suggesting that 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG was a better probe for in vivo PET imaging. Importantly, 15.5 %ID/g was one of the highest tumor uptakes that we can achieved based on EPR effects among all the studies using inorganic nanoparticles. In addition, strong uptake of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG was also observed in heart from 6 h to 48 h and there’s almost no uptake in other organs, which was basically consistent with blood circulation experiments (Figure 3a and 3b). It should be noted that the possibly remaining 1stPEG in the samples would affect the accuracy of PET imaging, since NOTA were conjugated on 1stPEG.41 To eliminate this concern, several purification methods were performed during the synthesis procedures.

The biodistribution studies of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG and 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG were carried out at 48 h p.i. to validate the PET results (Figure 5c). The biodistribution study and quantitative ROI analysis of PET data matched well. Even at 48 h p.i., the blood concentration of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (10.2 %ID/g) was greatly higher than that of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG (5.9 %ID/g), due to the longer blood circulation. The tumor, liver and spleen uptake of 64Cu-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG were 11.2, 24.6 and 14.1 %ID/g respectively. For non-renal clearable nanoparticles, the ratio of tumor-to-liver can be defined as tumor targeting specificity.13 The tumor-to-liver ratio of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (0.48) was significantly enhanced compared with 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG (0.29; p-value < 0.05), highlighting the superb passive tumor targeting efficiency of 64Cu-NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (Figure 5d).

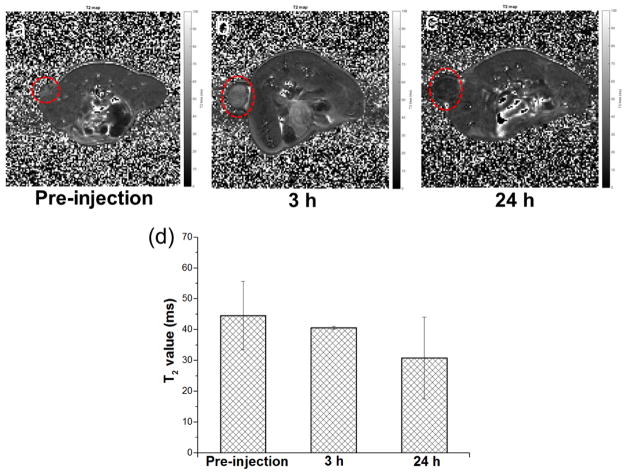

3.4 MR imaging and photoacoustic imaging

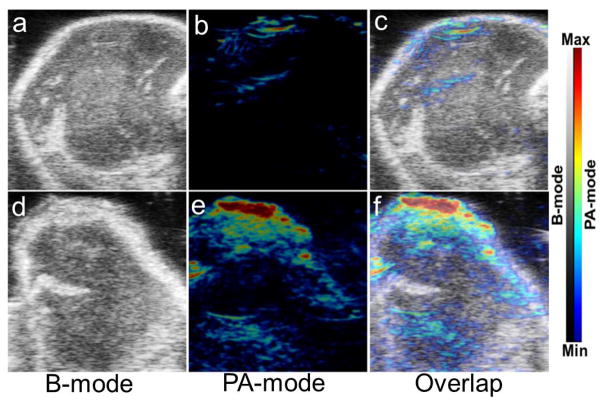

PET imaging provides high sensitivity and quantitative tracking of radiotracers, but lacks resolving morphology.42 MRI with high spatial resolution and PA imaging with deep tissue penetration were excellent complementary imaging techniques for PET. Therefore, NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG that combines excellent magnetic property from IONPs and superb photoacoustic capacity from RGO nanosheets could serve as a promising contrast agent for both MRI (Figure 6a–d) and PA imaging (Figure 6e–j).

Figure 6.

In vivo MR imaging. In vivo T2-mapped MR imaging acquired before (a) and after 3 h (b) and 24 h (c) intravenous injection of 400 μL NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (dose: 5.8 mg Fe/Kg) in the same 4T1 tumor-bearing mice (n = 2). (d) shows the comparison of the T2 values acquired from the tumors in the mice before and after intravenous injection of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG.

In vivo T2-mapped MR imaging of 4T1 tumor-bearing mice were conducted before and after intravenous injection of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG solution with the dose of 5.8 mg Fe/Kg. Darkening effect with shorter T2 was observed in the tumor of mice at 3 h post-injection of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (T2 = 40.62 ± 0.44 ms, Figure 6b and 6d) and obviously enhanced at 24 h post-injection (T2 = 30.83 ± 13.30 ms, Figure 6c and 6d), compared with the same mice before the injection of nanoparticles (T2 = 44.59 ± 11.07 ms, Figure 6a and 6d), indicating passive accumulation of NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG in the tumor. Since MRI is of low sensitive and MR contrast highly depends on the dose of magnetic probes, better contrast image could be achieved by increasing the concentration of injected nanoparticles.

Owing to their ability to absorb light at a wide range of wavelengths, especially in near infrared region, RGO-based nanomaterials are natural contrast agents for PA imaging. 4T1 tumor-bearing mice in treated group were intravenously injected with NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG. Comparing to the control group (PBS injected, Figure 7a–7c), significant stronger photoacoustic signal was observed from tumor in the treated group (Figure 7d–7f). Considering that imaging and MRI display the real biodistribution of the nanoparticles, multimodality imaging combining PA and MRI successfully confirmed that NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG indeed accumulated in the tumor site, further demonstrating the accuracy of PET imaging.

Figure 7.

In vivo PA imaging. (a), (b) and (c) were the PA images of the tumor part in 4T1 tumor-bearing mouse with intravenous injection of 150 μL PBS (control group); (d), (e) and (f) were the PA images of the tumor part in 4T1 tumor-bearing mouse with intravenous injection of 150 μL NOTA-RGO-IONP-1stPEG-2ndPEG (0.3 mg/ml, treated group).

4. Conclusions

In summary, long-circulating and double-PEGylated RGO-IONP nanoparticles were developed and radiolabeled with 64Cu for multimodality (PET/MR/PA) imaging with enhanced passive tumor targeting efficacy. To the best of our knowledge, tumor accumulation of ~15.5 %ID/g was among the best achieved by inorganic nanomaterials. Our study indicates that optimization of surface PEGylation can improve in vivo bioproperties of nanoparticles. And triple-modal PET/MR/PA in vivo tumor imaging by using RGO-IONP nanocomposites provided multi-aspect, more accurate and complete information for tumor diagnosis and therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported, in part, by the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the National Institutes of Health (NIBIB/NCI 1R01CA169365, P30CA014520, T32CA009206 and T32GM008505), the American Cancer Society (125246-RSG-13-099-01-CCE), Wisconsin Distinguished Graduate Fellowship, the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, 2012CB932601) and the grant of China Scholarship Council. We also gratefully acknowledge the Analytical Instrumentation Center of the School of Pharmacy at University of Wisconsin–Madison for obtaining FT-IR spectra.

References

- 1.Hong G, Diao S, Antaris AL, Dai H. Chem Rev. 2015;115:10816–10906. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee N, Yoo D, Ling D, Cho MH, Hyeon T, Cheon J. Chem Rev. 2015;115:10637–10689. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jokerst JV, Lobovkina T, Zare RN, Gambhir SS. Nanomedicine. 2011;6:715–728. doi: 10.2217/nnm.11.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu C, Yang D, Mei L, Lu B, Chen L, Li Q, Zhu H, Wang T. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5:2715–2724. doi: 10.1021/am400212j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han X, Li Z, Sun J, Luo C, Li L, Liu Y, Du Y, Qiu S, Ai X, Wu C, Lian H, He Z. J Control Release. 2015;197:29–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pozzi D, Colapicchioni V, Caracciolo G, Piovesana S, Capriotti AL, Palchetti S, De Grossi S, Riccioli A, Amenitsch H, Lagana A. Nanoscale. 2014;6:2782–2792. doi: 10.1039/c3nr05559k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shi S, Huang Y, Chen X, Weng J, Zheng N. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2015;7:14369–14375. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b03106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu Z, Cai W, He L, Nakayama N, Chen K, Sun X, Chen X, Dai H. Nat Nanotechnol. 2007;2:47–52. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Prencipe G, Tabakman SM, Welsher K, Liu Z, Goodwin AP, Zhang L, Henry J, Dai H. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4783–4787. doi: 10.1021/ja809086q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi S, Chen F, Ehlerding EB, Cai W. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25:1609–1619. doi: 10.1021/bc500332c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu T, Shi S, Liang C, Shen S, Cheng L, Wang C, Song X, Goel S, Barnhart TE, Cai W, Liu Z. ACS Nano. 2015;9:950–960. doi: 10.1021/nn506757x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knop K, Hoogenboom R, Fischer D, Schubert US. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:6288–6308. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yu M, Zheng J. ACS Nano. 2015;9:6655–6674. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.5b01320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maeda H, Wu J, Sawa T, Matsumura Y, Hori K. J Control Release. 2000;65:271–284. doi: 10.1016/s0168-3659(99)00248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu X, Tao H, Yang K, Zhang S, Lee ST, Liu Z. Biomaterials. 2011;32:144–151. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen F, Cai W. Small. 2014;10:1887–1893. doi: 10.1002/smll.201303627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sheng Z, Song L, Zheng J, Hu D, He M, Zheng M, Gao G, Gong P, Zhang P, Ma Y, Cai L. Biomaterials. 2013;34:5236–5243. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu C, Yang D, Mei L, Li Q, Zhu H, Wang T. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2013;5:12911–12920. doi: 10.1021/am404714w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen L, Zhong X, Yi X, Huang M, Ning P, Liu T, Ge C, Chai Z, Liu Z, Yang K. Biomaterials. 2015;66:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang W, Guo Z, Huang D, Liu Z, Guo X, Zhong H. Biomaterials. 2011;32:8555–8561. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng L, Zhang S, Liu Z. Nanoscale. 2011;3:1252–1257. doi: 10.1039/c0nr00680g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang K, Feng L, Hong H, Cai W, Liu Z. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2392–2403. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong H, Yang K, Zhang Y, Engle JW, Feng L, Yang Y, Nayak TR, Goel S, Bean J, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Liu Z, Cai W. ACS Nano. 2012;6:2361–2370. doi: 10.1021/nn204625e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shi S, Yang K, Hong H, Chen F, Valdovinos HF, Goel S, Barnhart TE, Liu Z, Cai W. Biomaterials. 2015;39:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shi S, Yang K, Hong H, Valdovinos HF, Nayak TR, Zhang Y, Theuer CP, Barnhart TE, Liu Z, Cai W. Biomaterials. 2013;34:3002–3009. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee S, Kang SW, Ryu JH, Na JH, Lee DE, Han SJ, Kang CM, Choe YS, Lee KC, Leary JF, Choi K, Lee KH, Kim K. Bioconjug Chem. 2014;25:601–610. doi: 10.1021/bc500020g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jokerst JV, Cole AJ, Van de Sompel D, Gambhir SS. ACS Nano. 2012;6:10366–10377. doi: 10.1021/nn304347g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen F, Ellison PA, Lewis CM, Hong H, Zhang Y, Shi S, Hernandez R, Meyerand ME, Barnhart TE, Cai W. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2013;52:13319–13323. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de la Zerda A, Kim JW, Galanzha EI, Gambhir SS, Zharov VP. Contrast Media Mol Imaging. 2011;6:346–369. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang K, Hu L, Ma X, Ye S, Cheng L, Shi X, Li C, Li Y, Liu Z. Adv Mater. 2012;24:1868–1872. doi: 10.1002/adma.201104964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rieffel J, Chitgupi U, Lovell JF. Small. 2015;11:4445–4461. doi: 10.1002/smll.201500735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarrett BR, Gustafsson B, Kukis DL, Louie AY. Bioconjug Chem. 2008;19:1496–1504. doi: 10.1021/bc800108v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rieffel J, Chen F, Kim J, Chen G, Shao W, Shao S, Chitgupi U, Hernandez R, Graves SA, Nickles RJ, Prasad PN, Kim C, Cai W, Lovell JF. Adv Mater. 2015;27:1785–1790. doi: 10.1002/adma.201404739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chakravarty R, Valdovinos HF, Chen F, Lewis CM, Ellison PA, Luo H, Meyerand ME, Nickles RJ, Cai W. Adv Mater. 2014;26:5119–5123. doi: 10.1002/adma.201401372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu H, Cheng L, Wang C, Ma X, Li Y, Liu Z. Biomaterials. 2011;32:9364–9373. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.08.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan Q, Cheng K, Hu X, Ma X, Zhang R, Yang M, Lu X, Xing L, Huang W, Gambhir SS, Cheng Z. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:15185–15194. doi: 10.1021/ja505412p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sun H, Cao L, Lu L. Nano Res. 2011;4:550–562. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang C, Cheng L, Liu Z. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1110–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harper JC, Polsky R, Wheeler DR, Brozik SM. Langmuir. 2008;24:2206–2211. doi: 10.1021/la702613e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li SD, Huang L. Mol Pharm. 2008;5:496–504. doi: 10.1021/mp800049w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gong H, Dong Z, Liu Y, Yin S, Cheng L, Xi W, Xiang J, Liu K, Li Y, Liu Z. Adv Funct Mater. 2014;24:6492–6502. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Judenhofer MS, Wehrl HF, Newport DF, Catana C, Siegel SB, Becker M, Thielscher A, Kneilling M, Lichy MP, Eichner M, Klingel K, Reischl G, Widmaier S, Rocken M, Nutt RE, Machulla HJ, Uludag K, Cherry SR, Claussen CD, Pichler BJ. Nat Med. 2008;14:459–465. doi: 10.1038/nm1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]