Abstract

Background

Numerous cross-sectional studies have related exposure to neurotropic infectious agents with cognitive dysfunction in older adults, but the temporal sequence is uncertain.

Methods

In a representative, well-characterized, population-based aging cohort, we determined whether the temporal trajectories of multiple cognitive domains are associated with exposure to cytomegalovirus (CMV), Herpes Simplex virus, type 1 (HSV-1), Herpes Simplex virus, type 2 (HSV-2) or Toxoplasma gondii (TOX). Complex attention, executive functions, memory, language, and visuospatial function were assessed annually for five years among consenting individuals. Study entry IgG antibody titers indexing exposure to each infectious agent were examined in relation to slopes of subsequent temporal cognitive decline using multiple linear regressions adjusted for potential confounders.

Results

The IgG levels for HSV-2 were significantly associated with baseline cognitive domain scores (N=1022 participants). Further, the IgG levels for HSV-2, TOX and CMV, but not HSV-1 were significantly associated with greater temporal cognitive decline that varied by type of infection.

Conclusions

Exposure to CMV, HSV-2, or TOX is associated with cognitive deterioration in older individuals, independent of general age related variables. An increased understanding of the role of infectious agents in cognitive decline may lead to new methods for its prevention and treatment.

Keywords: epidemiology, aging, community, CMV, herpes virus, cognition, Toxoplasma gondii

Introduction

The number of persons aged 60 years and older will double to 1.2 billion people worldwide by 2025 (http://www.who.int/ageing/en/index.html). Cognitive impairment is a substantial challenge for health care and social support in this age group, compelling the need to identify risk factors that could be targeted for prevention or treatment. One potential group of targets comprises infectious agents that can cause lifelong infection in the brain. As chances of virus exposure increase with age, with unpredictable recurrences that can cause neuronal injury, it is possible that such infections contribute to the overall cognitive impairment observed in an aging population. Many previous cross-sectional studies in aging adults have indicated an association between decreased cognitive functioning and exposure to neurotropic infectious agents including Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV-1), 1,2,3,4,5-7,8,9,10,11,12, Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 (HSV-2) 2, Cytomegalovirus 13,14,15,16,10, and Toxoplasma gondii (TOX) 17. Still, the temporal sequence underlying the associations is uncertain, and causal inferences can therefore not be made. There have been few longitudinal studies examining the relationship between exposure to infectious agents and cognitive decline. One study found an association between exposure to CMV and cognitive decline over a 4 year period in cohort of 1,204 Latino individuals 18. Another study documented an association between IgG antibodies to CMV and cognitive decline and to the development of AD in a cohort of 849 individuals 19. In these studies, an association was not found between antibodies to HSV-1 and cognitive decline. An association between IgG antibodies to CMV and cognitive decline was also found in a smaller cohort reported by Carbone et al, but antibodies to HSV-1 were not measured in this study 20. There have been no studies examining cognitive decline and antibodies to HSV-2 or TOX.

In the present study, we investigated samples from the ‘Monongahela–Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team’ (MYHAT) study, in which a population-based cohort of participants 65 years and older was evaluated annually for five years to investigate cognitive change over time 21,22. We assessed the contribution of exposure to CMV, HSV-1, HSV-2 or TOX to cognitive dysfunction at study entry and longitudinal cognitive decline, taking into account potential confounding factors.

Methods

Study site and population

MYHAT is an age-stratified random population sample drawn from the publicly available voter registration lists for a small-town region of Pennsylvania (USA). These communities were formerly the hub of the now largely inactive steel industry and have remained economically disadvantaged since the collapse of that industry in the 1970s. The population is stable, i.e., characterized by low rates of in- and out-migration (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19340894 ).

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations and Consents

Community outreach, recruitment, and assessment protocols were approved by the University of Pittsburgh IRB for protection of human subjects. All participants provided written informed consent. Recruitment criteria were (a) age 65 years or older, (b) living within the selected towns, and (c) not already in long-term care institutions. Individuals were ineligible if they (a) were too ill to participate, (b) had severe vision or hearing impairments, or (c) were decisionally incapacitated. We recruited 2036 individuals, screening out at study entry those who exhibited substantial impairment by scoring <21/30 on an age-education-corrected Mini-Mental State Evaluation (MMSE) 23, as the project was designed to study mild impairment. The remaining 1982 individuals were representative of older adults in the targeted communities, with mean (SD) age of 77.6 (7.4) years; they were 61.0% female; 94.7% of mixed European descent, and had median educational level of high school graduate (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19340894).

Assessment

Cognitive Assessment

At study entry (baseline) and at each annual follow-up wave, the assessment included a neuropsychological battery designed to test general cognitive function (MMSE) 23, as well as the cognitive domains of attention, executive function, learning/memory, language, and visuospatial function 24. To create a composite score for each domain, we transformed each test score within that domain into a standardized score by centering to its baseline mean value and dividing by its baseline standard deviation, and then calculated the arithmetic mean of all the standardized scores within that domain. These composite scores were examined in the cross-sectional analyses (see Statistical Analysis), and were used to calculate slope of cognitive decline over time in the longitudinal analyses.

Laboratory tests

Each participant was asked to provide non-fasting venous blood samples at study entry; some participants provided these specimens one year later instead. Banked serum specimens were sent with appropriate material transfer agreement to the Stanley Neurovirology lab, Johns Hopkins University (JHU) where they were assayed for exposure to CMV. Antibodies to HSV-1, HSV-2 and TOX were assayed similarly. We used highly sensitive micro-plate solid-phase enzyme immunoassays (ELISA) for immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody detection 1. Assay kits were obtained from IBL America, Minneapolis, Minnesota (Toxo CMV) and Focus Diagnostics, Cypress, Ca (HSV-1, HSV-2). The assays for HSV-1 and HSV-2 employed purified glycoproteins, while the assays for CMV and TOX used whole organisms as the target antigen. Reference samples were placed on every plate to standardize the results. The levels were adjusted, employing the reference standards in each microplate and for each sample, the level of antibody was expressed as the ratio of the sample signal and the mean reference standard on the same microplate. Exposure to an infectious agent was defined by seropositivity, i.e., the presence of a level of antibody greater than the cutoff, as provided by the manufacturer.

Statistical Analysis

Each set of antibodies was dichotomized based on the distribution as described above. We examined baseline relationships between seropositivity for each infectious agent and the demographics [age, gender, race (white and nonwhite), APOE*4 carrier status, and education (less than high school and high school or more)] using univariable logistic regression with the corresponding odds ratios (Supplementary Table S1, see Supplemental Digital Content). Multiple linear regression models adjusting for demographics were fit to access the effect of antibody levels on each cognitive domain composite and MMSE at baseline (Table 1).

Table 1. Associations of baseline cognitive domain composite and MMSE scores with seropositivity for antibodies to infectious agents.

| Infectious agent and proportion of individuals exposed1 | CMV | HSV-1 | HSV-2 | TOX |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 83% | 78% | 10% | 48% | |

| Cognitive domains: | β (P value)2 | β (P value)2 | β (P value)2 | β (P value)2 |

| Attention | 0.0754 (NS) |

0.0613 (NS) |

-0.1745 (0.017) |

-0.0046 (NS) |

| Executive function | 0.0314 (NS) |

-0.0193 (NS) |

-0.2017 (0.003) |

-0.0766 (NS) |

| Memory | -0.0217 (NS) |

-0.0936 (NS) |

-0.2264 (0.002) |

-0.0706 (NS) |

| Language | 0.0161 (NS) |

-0.0575 (NS) |

-0.3046 (<0.001) |

-0.0465 (NS) |

| Visuospatial function | 0.0327 (NS) |

-0.0147 (NS) |

-0.4153 (<0.001) |

-0.1033 (NS) |

| MMSE | -0.0809 (NS) |

0.0852 (NS) |

-0.6047 (0.006) |

-0.0816 (NS) |

The proportion of individuals exposed to each infections agent was estimated using pre-determined cutoffs in antibody levels, see Methods.

β coefficients (P values) derived from separate regression analyses for each infectious agent, with individual cognitive domains as outcomes and seropositivity to infectious agents as predictors, adjusted for age, gender and educational status.

CMV: Cytomegalovirus, HSV-1: Herpes Simplex virus, type 1; HSV-2: Herpes Simplex virus, type 2; TOX: Toxoplasma gondii; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; NS: not significant.

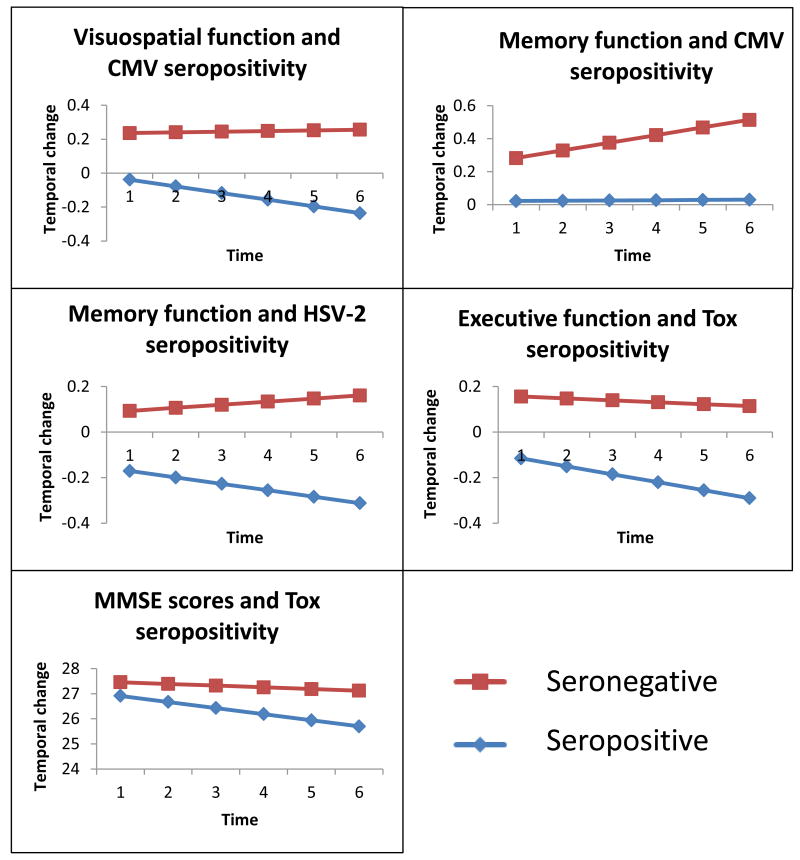

A two-stage modeling approach was applied to explore the effect of antibody levels on subsequent change in each cognitive domain composite and MMSE25. In the first stage, the rate (slope) of change for each subject in each domain was estimated using a linear mixed model; only individuals with available sera were analyzed. The obtained slopes then served as the outcome variable for the next stage, in which we used linear regression to evaluate the association between infectious exposure and temporal change in cognitive functions. Both univariable linear regression and multiple linear regression models adjusting for demographics were fit for seropositivity assayed through antibody levels. After identifying the significant associations between antibody levels and temporal changes in cognitive domains, average changes in these cognitive domains between the exposed group and nonexposed group for specific virus variables were plotted using the estimated fixed effects from the mixed models.

Results

Of the 1982 individuals who underwent the full assessment at study entry, 1022 provided usable serum specimens. The mean age of this sub-group was 77.5 years (standard deviation, SD, 7.5); 60% were women; 4.9% reported African-American ancestry; 12.5%, 46.3%, and 41.2% had less than high school, were high school graduates, or obtained more than high school education, respectively. In the sample, 21% were carriers of the APOE*4 allele. Participants who did and did not provide serum specimens did not have statistically significant differences in age (Mean, SD: 77.47, 7.49 and 77.84, 7.39 years respectively), proportion of women (59.6% and 62.6%), proportions self-reported as white (95.6% and 93.8%) and proportions with one or more APOE*4 alleles (20.8% and 21.1%). The mean (SD) MMSE scores of those with and without serum were 27.06 (2.36) and 26.81 (2.50). This relatively small difference of less than one MMSE point attained statistical significance, possibly due to the relatively large sample (p=0.021).

Potential predictors of antibody levels at study entry

The thresholds of seropositivity used to classify individuals as “exposed” varied by infectious agent (see Statistical Analysis). There were 850 individuals who were classified as CMV antibody positive (83.2%) based on a threshold of 2 units; this level was subsequently used to categorize individuals as ‘exposed’ or ‘not exposed’ (see the statistical analysis section) 1,8. Employing appropriate cutoff values, the seropositivity rate was 77.7% for HSV-1, 10.4% for HSV-2 and 47.9% for TOX. The association between seropositivity and demographic variables is depicted in Supplementary table S1 (Supplemental Digital Content). IgG levels for the antibodies to CMV, HSV-1 and TOX were associated with greater age, female gender, and level of education. Only TOX seropositivity was associated with the APOE*4 allele. Though an association with ethnicity was noted with regard to HSV-1 and HSV-2 seropositivity, only 4.9% of the sample reported African-American ethnicity and there were no Latinos. Therefore, in subsequent analyses, only the effects of age, gender and educational level, but not ethnicity were covaried.

Antibody levels and cognitive functions at study entry

In unadjusted cross-sectional analyses, exposure to several infectious agents was significantly associated with lower cognitive domain composite scores in all cognitive domains except attention and with lower MMSE scores (Supplementary Table S2, see Supplemental Digital Content). After adjustment for age, gender, and education, however, significant associations remained only between seropositivity for HSV-2 and all of the measured cognitive domains (Table 1; Supplementary Table S2, Supplemental Digital Content).

Seropositivity and temporal change in cognitive functions

The overall distribution of cognitive changes (mean, SD of the slope) for each domain are shown in Supplementary Table S3 (Supplemental Digital Content). The average slope of 5-year scores was negative for all cognitive domains except for the memory domain, indicating that those cognitive domains and MMSE (but not memory) declined on average. Supplementary Table S4 (see Supplemental Digital Content) presents the average (SD) slope of 5-year cognitive scores for each domain by IgG antibody level (seropositive or seronegative) and the significant results are presented graphically in Figure 1. In general, the cognitive domains and MMSE, declined less rapidly among IgG negative participants. Different patterns of association between seropositivity and slopes of change in cognitive domains emerged in longitudinal analyses adjusted for age, gender and education (Table 2, Figure 1). CMV seropositivity was significantly associated with differing trajectories of the memory domain (i.e., lack of expected practice effect over time) and visuospatial domain (i.e., greater decline), while HSV-2 exposure was associated with greater decline in the memory domain alone and TOX was associated with more rapid decline in executive function and changes in MMSE scores. HSV-1 seropositivity was not associated with any of the cognitive domains or with MMSE scores.

Figure 1. Significantly greater temporal decline in cognitive domains / MMSE scores associated with seropositivity (exposure).

Antibody levels were dichotomized using pre-determined cutoff values and seropositivity used to indicate infectious exposure. The cognitive domains that showed significantly greater temporal decline among seropositive (exposed) individuals in Table 2 are graphed. The estimated average changes in these cognitive domains between the exposed group and unexposed group for each infection were plotted against annual evaluations using fixed effects of mixed models. CMV: Cytomegalovirus; HSV-2: Herpes Simplex virus, type 2; TOX: Toxoplasma gondii; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination.

Table 2. Temporal changes in cognitive domain composite scores and seropositivity for antibodies to infectious agents.

| CMV | HSV-1 | HSV-2 | TOX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive domains: | β (P value)1 | β (P value)1 | β (P value)1 | β (P value)1 |

| Attention | -0.0027 (NS) |

0.0008 (NS) |

-0.0069 (NS) |

-0.0014 (NS) |

| Executive function | -0.0075 (NS) |

0.0043 (NS) |

-0.0043 (NS) |

-0.0074 (0.04) |

| Memory |

-0.0149 (0.04) |

-0.0033 (NS) |

-0.0238 (0.005) |

-0.0044 (NS) |

| Language | -0.0083 (NS) |

-0.0052 (NS) |

-0.0086 (NS) |

-0.0050 (NS) |

| Visuospatial function |

-0.0123 (0.04) |

-0.0076 (NS) |

0.0137 (NS) |

0.0013 (NS) |

| MMSE | -0.0336 (NS) |

-0.0208 (NS) |

-0.0426 (NS) |

-0.0664 (0.007) |

β coefficients (P values) derived from separate regression analyses for each infectious agent, with temporal trajectories of individual cognitive domains as outcomes and seropositivity to infectious agents as predictors, adjusted for age, gender and educational status (negative value indicate greater relative cognitive decline).

CMV: Cytomegalovirus, HSV-1: Herpes Simplex virus, type 1; HSV-2: Herpes Simplex virus, type 2; TOX: Toxoplasma gondii; MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; NS: not significant.

Discussion

Through repeated assessment of the population-based MYHAT cohort, the temporal trajectory of cognitive changes was assessed in relation to four common infectious agents that can cause cerebral infection; we found significant associations with exposure to CMV, HSV-2 and TOX but not with HSV-1. The associations are unlikely to reflect the sequelae or prior encephalitis due to any of these agents, in view of the exclusion criteria applied in the study. The associations were most significant for HSV-2 exposure and temporal decline in the domain of memory. HSV-2 seropositivity was also associated with lower performance on several cognitive domains at baseline, even when controlling for potential confounding variables. These findings are unexpected, given the paucity of previous studies of cognitive consequences of HSV-2 infections. Since HSV-2 is largely sexually transmitted, it is also possible that HSV-2 positivity is a marker for other sexually transmitted disorders or sexual behaviors which are themselves associated with cognitive impairments and cognitive decline. HSV-2 can establish latency within the brains of experimental animals26 and occasionally cause encephalitis in immune competent older adults 27. It is thus possible that HSV-2 can contribute to cognitive impairments in some individuals. Active HSV-2 infections can be treated effectively with available antiviral medications and the rate of HSV-2 transmission can be decreased by the use of antiviral therapy and safe sexual practices. If confirmed, a direct association between HSV-2 infections and cognitive impairment and cognitive decline thus might provide additional modalities for the prevention and treatment of cognitive impairments in some individuals.

In addition to HSV-2, we found a significant association between seropositivity to TOX and a decline in the domain of executive functioning and MMSE scores. While TOX infections in immune competent individuals have been previously considered to be asymptomatic, recent studies have indicated that latent forms of Toxoplasma can be associated with behavioral anxiety disorders 28 and cognitive impairment 29 in some populations. Our findings indicate that serological evidence of exposure to TOX could also be associated with cognitive decline in aging individuals. Additional populations should be assessed in order to document the generalizability of this finding. There are currently no available medications which can effectively treat the tissue cyst form of TOX 30. However, Toxoplasma transmission can be prevented by a number of public health measures including the freezing and adequate cooking of meat which might contain tissue cysts and the purification of drinking water which might contain oocysts31.

Our finding of an association between serological evidence of exposure to CMV and cognitive decline confirms and extends the results of two prior longitudinal analyses. A prospective cohort based study showed elevated rates of cognitive decline over four years among Mexican-Americans with elevated CMV antibody levels18. Cognitive function was only assessed in that study using the Mini Mental State Examination. In another recent study, CMV seropositivity was associated with an even higher rate of decline when a more comprehensive and sensitive estimate of global cognition was estimated 19. This study also related CMV exposure to increased risk of Alzheimer's disease (AD, relative risk, 2.15). CMV as a putative risk factor for cognitive decline has enormous public health impact because individuals of all ages are prone to infection - starting in the intra-uterine period - to older US adults for whom seropositivity rates can exceed 90% (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm) 13. CMV primarily infects lymphoid tissues and salivary glands, but infection can also occur in the brain 14. Viral DNA has also been detected in non-encephalitic post-mortem brain tissues, suggesting viral spread to the brain during persistent infection 15.

The Institute of Medicine recently published a report on ‘Cognitive Aging’ to draw attention to incremental cognitive dysfunction as we age (http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2015/Cognitive-Aging.aspx). Our results suggest that a portion of cognitive aging could be attributed to chronic exposure to particular infectious agents. Another possibility is that such infections decreases “brain reserve”, making the brain more susceptible to other insults such as cerebrovascular disease. In the case of CMV, there are several plausible mechanisms for the infection-related cognitive decline, while others can be discounted. The association could be mediated by exaggerated or altered immunological responses to the target agent that has been noted in older individuals 32,33. Because CMV infection is common in lymphatic tissues, it may alter the immune response to other infectious organisms or inflammation too 34. Cognitive decline related to direct cytopathic effects of CMV, sub-clinical reactivation, or CMV-associated cardiovascular dysfunction are plausible 35. Cognitive decline could also reflect secondary neurotoxic effects of cytokines released peripherally during reactivation or even antigen- related ‘immunosenescence’ 36,37,38. Others have suggested that the links between CMV and other viral infections and the different effects on memory could relate to more generalized immune dysregulation with more direct neuronal damage, such as HSV-1 11. Further work exploring more specific immune markers such as interferons and interleukins will be necessary to follow up this work. Some infectious agents, particularly CMV have been suggested as risk factors for vascular disease, indicating another possible link between infectious agents and cognitive dysfunction 19. Though a prior study did not find any evidence for such a link, it may be instructive to investigate the role of vascular risk factors 19. The observed changes are unlikely to reflect a general decline in health, as only certain cognitive domains were affected. Since they have been less frequently studied, the possible associations between cognitive impairment and TOX and HSV-2 are less well defined. In the case of TOX, it is of note that the experimental infection of mice can result in cognitive impairment with some variation dependent upon the strain of Toxoplasma and the strain of mice. The mechanisms are not known, but may related to both direct effect of the parasite on the brain as well as the host response to infection39. Additional studies should be directed at possible mechanisms linking TOX exposure to cognitive decline in aging adults. In summary, several mechanisms could explain the associations, including effects specific to each agent, or more general immunological sequelae of infection.

Contrary to other studies which have demonstrated an increased risk of AD associated with HSV-1 exposure, we did not find any significant association with memory or any cognitive dysfunction 35. Our findings are consistent with those of Aiello et al and Barnes et al which also did not find associations between serological exposure to HSV-1 and cognitive decline 12,19. The lack of finding of an association between exposure to HSV-1 and cognitive decline does not rule out any role for HSV-1, since the type specific assays which were used do not have sufficient sensitivity to detect different stages of HSV-1 infection.

Some limitations of our analyses should be noted. CMV, TOX and HSV-2 exposure rates for ethnic minority communities in the US are relatively high 40; and greater cognitive decline has been reported among CMV-exposed African-Americans 19. We could not detect a similar pattern, likely because African-Americans formed only 5% of the MYHAT sample. For the same reason, the potential confounding effect of ethnic differences in seroprevalence rates, could not be analyzed meaningfully. Socio-economic status (SES) is strongly correlated with exposure to many infectious agents, with poorer individuals experiencing higher infection rates. As educational attainment is the most reliable and accurate measure of SES in our sample, we included it as a covariate in our analyses relating infectious agent to cognitive function. Since it is difficult to accurately measure many neurotropic infectious agents directly in blood samples, antibody levels were used as proxies for exposure. Though the antibody assays are highly sensitive and specific, it is not possible to estimate the timing or duration of exposure. As we tested associations reported previously and as exposure to infectious agents is correlated, the appropriate level of correction for multiple comparisons is difficult to determine. Despite the relatively large size, the sample did not have sufficient power to examine the interaction of exposures to multiple infectious agents; larger samples should be analyzed. Lifestyle related factors, host related immune factors or other infections can also be associated with temporal changes in cognition. These variables are often correlated, so it can be difficult to tease out their individual effects. On the other hand, the different effect sizes noted here for the infectious agents, and their differing temporal trajectories suggest that some effects could be related to individual infectious agents.

In conclusion, our analyses indicate that CMV, HSV-2 or TOX exposure are associated with cognitive decline in older persons, explaining a small but significant proportion of what is generally dismissed as age-related decline. The results are important from a public health perspective, as CMV, HSV-2 and TOX infections are highly prevalent, and several options for prevention and treatment are available. A randomized controlled trial of suitable pharmacotherapy could also further test the associations; if successful, it would suggest a potential therapeutic option for older adults. An increased understanding of the role of infectious agents may ultimately indicate preventive measures.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table S1. Association of demographic and clinical variables with seropositivity for antibodies to infectious agents.

Supplementary Table S2. Cognitive domains associated with seropositivity at study entry.

Supplementary Table S3. Estimated slopes for temporal changes in cognitive domains and MMSE scores.

Supplementary Table S4. Average slopes of 5-year scores for cognitive domains and MMSE by IgG antibody levels.

Acknowledgments

Funding support: This work was supported in part by grants # R01 AG02365 and K07 AG044395 and AG020677 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA), MH09375 from NIMH and 07R-1712 from the Stanley Medical Research Institute. The authors declare no conflicts of interest in relation to this work. The funding agencies are not responsible for the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; nor for preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

We thank our research participants and study personnel. We thank Mr Joel Wood for help with data management and manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.Dickerson FB, Boronow JJ, Stallings C, et al. Association of serum antibodies to herpes simplex virus 1 with cognitive deficits in individuals with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(5):466–472. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.5.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strandberg TE, Pitkala KH, Linnavuori KH, et al. Impact of viral and bacterial burden on cognitive impairment in elderly persons with cardiovascular diseases. Stroke. 2003;34(9):2126–2131. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000086754.32238.DA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shirts BH, Prasad KM, Pogue-Geile MF, et al. Antibodies to cytomegalovirus and Herpes Simplex Virus 1 associated with cognitive function in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2008;106(2-3):268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yolken RH, Torrey EF, Lieberman JA, et al. Serological evidence of exposure to Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 is associated with cognitive deficits in the CATIE schizophrenia sample. Schizophr Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.01.020. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schretlen DJ, Vannorsdall TD, Winicki JM, et al. Neuroanatomic and cognitive abnormalities related to herpes simplex virus type 1 in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2010;118(1-3):224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dickerson F, Stallings C, Origoni A, et al. Additive effects of elevated C-reactive protein and exposure to Herpes Simplex Virus type 1 on cognitive impairment in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;134(1):83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dickerson FB, Boronow JJ, Stallings C, et al. Infection with herpes simplex virus type 1 is associated with cognitive deficits in bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;55(6):588–593. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Watson AM, Prasad KM, Klei L, Wood JA, et al. Persistent infection with neurotropic herpes viruses and cognitive impairment. Psychol Med. 2013;43(5):1023–1031. doi: 10.1017/S003329171200195X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickerson F, Stallings C, Sullens A, et al. Association between cognitive functioning, exposure to Herpes Simplex Virus type 1, and the COMT Val158Met genetic polymorphism in adults without a psychiatric disorder. Brain Behav Immun. 2008;22(7):1103–1107. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.04.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prasad KM, Watson AM, et al. Exposure to herpes simplex virus type 1 and cognitive impairments in individuals with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(6):1137–1148. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarter KD, Simanek AM, Dowd JB, et al. Persistent viral pathogens and cognitive impairment across the life course in the third national health and nutrition examination survey. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2014;209(6):837–844. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aiello AE, Haan MN, Pierce CM, et al. Persistent infection, inflammation, and functional impairment in older Latinos. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(6):610–618. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.6.610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staras SA, Dollard SC, Radford KW, et al. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the United States, 1988-1994. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(9):1143–1151. doi: 10.1086/508173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmutzhard E. Viral infections of the CNS with special emphasis on herpes simplex infections. J Neurol. 2001;248(6):469–477. doi: 10.1007/s004150170155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin WR, Wozniak MA, Wilcock GK, et al. Cytomegalovirus is present in a very high proportion of brains from vascular dementia patients. Neurobiol Dis. 2002;9(1):82–87. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.2001.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strandberg TE, Pitkala K, Eerola J, et al. Interaction of herpesviridae, APOE gene, and education in cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2005;26(7):1001–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gajewski PD, Falkenstein M, Hengstler JG, et al. Toxoplasma gondii impairs memory in infected seniors. Brain Behav Immun. 2014;36:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2013.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aiello AE, Haan M, Blythe L, et al. The influence of latent viral infection on rate of cognitive decline over 4 years. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(7):1046–1054. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes LL, Capuano AW, Aiello AE, et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection and Risk of Alzheimer Disease in Older Black and White Individuals. J Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiu437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carbone I, Lazzarotto T, Ianni M, et al. Herpes virus in Alzheimer's disease: relation to progression of the disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2014;35(1):122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ganguli M, Snitz B, Vander Bilt J, et al. How much do depressive symptoms affect cognition at the population level? The Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team (MYHAT) study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(11):1277–1284. doi: 10.1002/gps.2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganguli M, Fu B, Snitz BE, et al. Vascular risk factors and cognitive decline in a population sample. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders. 2013 doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mungas D, Marshall SC, Weldon M, et al. Age and education correction of Mini-Mental State Examination for English and Spanish-speaking elderly. Neurology. 1996;46(3):700–706. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ganguli M, Snitz BE, Lee CW, et al. Age and education effects and norms on a cognitive test battery from a population-based cohort: the Monongahela-Youghiogheny Healthy Aging Team. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14(1):100–107. doi: 10.1080/13607860903071014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ganguli M, Fu B, Snitz BE, Unverzagt FW, et al. Vascular risk factors and cognitive decline in a population sample. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28(1):9–15. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang K, Mahalingam G, Imai Y, et al. Cell type specific accumulation of the major latency-associated transcript (LAT) of herpes simplex virus type 2 in LAT transgenic mice. Virology. 2009;386(1):79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barker KR, Sarafino-Wani R, Khanom A, et al. Encephalitis in an immunocompetent man. J Clin Virol. 2014;59(1):1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Markovitz AA, Simanek AM, Yolken RH, et al. Toxoplasma gondii and anxiety disorders in a community-based sample. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;43:192–197. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickerson F, Stallings C, Origoni A, et al. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii and cognitive functioning in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and nonpsychiatric controls. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202(8):589–593. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doggett JS, Nilsen A, Forquer I, et al. Endochin-like quinolones are highly efficacious against acute and latent experimental toxoplasmosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(39):15936–15941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208069109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Opsteegh M, Kortbeek TM, Havelaar AH, et al. Intervention Strategies to Reduce Human Toxoplasma gondii Disease Burden. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(1):101–107. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vescovini R, Biasini C, Fagnoni FF, et al. Massive load of functional effector CD4+ and CD8+ T cells against cytomegalovirus in very old subjects. J Immunol. 2007;179(6):4283–4291. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Herrup K. Reimagining Alzheimer's Disease-An Age-Based Hypothesis. Journal of Neuroscience. 2010;30(50):16755–16762. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4521-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wisniewski K, Jervis GA, Moretz RC, et al. Alzheimer neurofibrillary tangles in diseases other than senile and presenile dementia. Ann Neurol. 1979;5(3):288–294. doi: 10.1002/ana.410050311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Itzhaki RF. Herpes simplex virus type 1 and Alzheimer's disease: increasing evidence for a major role of the virus. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:202. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arfanakis K, Fleischman DA, Grisot G, et al. Systemic inflammation in non-demented elderly human subjects: brain microstructure and cognition. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e73107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fülöp T, Larbi A, Pawelec G. Human T cell aging and the impact of persistent viral infections. Front Immunol. 2013;4:271. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Feinberg BB, Tan NS, Donovan PK, et al. Immunomodulation of cellular cytotoxicity to herpes simplex virus infection in pregnancy by inhibition of eicosanoid metabolism. J Reprod Immunol. 1993;23(2):109–118. doi: 10.1016/0165-0378(93)90001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kannan G, Pletnikov MV. Toxoplasma gondii and cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: an animal model perspective. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(6):1155–1161. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zajacova A, Dowd JB, Aiello AE. Socioeconomic and race/ethnic patterns in persistent infection burden among U.S. adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(2):272–279. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table S1. Association of demographic and clinical variables with seropositivity for antibodies to infectious agents.

Supplementary Table S2. Cognitive domains associated with seropositivity at study entry.

Supplementary Table S3. Estimated slopes for temporal changes in cognitive domains and MMSE scores.

Supplementary Table S4. Average slopes of 5-year scores for cognitive domains and MMSE by IgG antibody levels.