Abstract

Melanoma is a metastatic cancer associated with poor survival. Here, we study a subpopulation of melanoma cancer cells displaying melanoma cancer stem cell (MCS cells) properties including elevated expression of stem cell markers, increased ability to survive as spheroids, and enhanced cell migration and invasion. We show that the Ezh2 stem cell survival protein is enriched in MCS cells and that Ezh2 knockdown or treatment with small molecule Ezh2 inhibitors, GSK126 or EPZ-6438, reduces Ezh2 activity. This reduction is associated with a reduced MCS cell spheroid formation, migration, and invasion. Moreover, the diet-derived cancer prevention agent, sulforaphane (SFN), suppresses MCS cell survival and this is associated with loss of Ezh2. Forced expression of Ezh2 partially reverses SFN suppression of MCS cell spheroid formation, migration, and invasion. A375 melanoma cell-derived MCS cells form rapidly growing tumors in immune-compromised mice and SFN treatment of these tumors reduces tumor growth and this is associated with reduced Ezh2 level and H3K27me3 formation, reduced matrix metalloproteinase expression, increased TIMP3 expression and increased apoptosis. These studies identify Ezh2 as a MCS cell marker and cancer stem cell prevention target, and suggest that SFN acts to reduce melanoma tumor formation via a mechanism that includes suppression of Ezh2 function.

Keywords: melanoma, Ezh2, sulforaphane, stem cell, cancer, epigenetic, polycomb, cancer prevention, cancer therapy

INTRODUCTION

Melanoma is an aggressive form of skin cancer that has a poor survival rate [1]. Patients with metastatic melanoma have a median survival between 3 and 11 months and the disease is often resistant to conventional therapy [1–4]. This is due, at least in part, to the resistance of the cancer stem cell population to therapy. The cancer stem cell model suggests that a small fraction of cancer cells possess the ability to initiate and sustain tumor growth [5]. Consistent with this model, the tumorigenic component of primary melanoma is not homogeneous, but rather consists of hierarchically ordered subpopulations of tumor cells. Cancer stem cells are known to be chemoresistant, resistant to immune-surveillance, and involved in tumor recurrence and metastasis [6]. The presence of a melanoma cancer stem cells has been controversial [7], but the bulk of the data suggests the presence of a subgroup of ABCB5- and CD271-positive cells that display a cancer stem cell phenotype [8]. Melanoma has been treated using small molecule kinase inhibitors; however, aggressive tumors eventually recur and cause mortality [1–4]. Thus, the design of new methods of preventing and treating melanoma is a priority.

Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) and polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) [9] suppress gene expression via covalent modification of selected histones [9–14] leading to reduced tumor suppressor protein expression. Ezh2 is a lysine methyltransferase and is the main catalytic protein of PRC2 (polycomb repressor complex 2) [15]. Ezh2 catalyzes trimethylation of lysine 27 of histone 3 (H3K27me3), an important step in polycomb-mediated silencing of gene expression [16]. Recent findings show that Ezh2 is upregulated in tumors and is an important driver of tumor development and progression that is often correlated with poor prognosis [16–18]. Polycomb genes have been reported to enhance melanoma cell survival [19–25] and metastasis [26], and Ezh2 acquisition of functional mutations have been identified in a subset (3%) of melanoma tumors [27]. Limited knowledge is available regarding the role of Ezh2 in melanoma cancer stem cells, except that Ezh2 is overexpressed in putative melanoma cancer stem cells at the tumor invasion front [28].

Sulforaphane (SFN) is an important cancer prevention agent [29]. Sulforaphane, 1-isothiocyanato-4-(methylsulfinyl) butane, is a natural isothiocyanate cancer preventive agent derived from broccoli and other cruciferous vegetables [29]. SFN is a particularly appealing as a cancer prevention and treatment agent, as it is highly bioavailable in blood and tissues and has no known side effects [30–33]. SFN has been shown to modulate the melanoma tumor environment and may be an important prevention/treatment option [34–38].

Here we identify Ezh2 as enriched in melanoma cancer stem cells (MCS cells) and show that Ezh2 knockdown or treatment with small molecule Ezh2 inhibitors reduces MCS cell spheroid formation, survival, invasion and migration. We further show that SFN treatment reduces Ezh2 level and H3K27me3 formation and that this is associated reduced matrix metalloproteinase expression, enhanced apoptosis and with reduced MCS cell survival. The present studies show that Ezh2 is an important SFN cancer prevention target in melanoma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and Reagents

Sodium pyruvate (11360-070), Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, 11960-077), 0.25% trypsin–EDTA (25200-056), and L-glutamine (25030-164) were purchased from Gibco (Grand Island, NY). Heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS, F4135) and anti-β-actin (A5441) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Cell lysis buffer (9803), anti-Suz12 (3737S), anti-TIMP3 (D74B10) and anti-Bmi-1 (2830S) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA). Ezh2 antibody (612667) was purchased from BD Transduction Laboratories. Anti-H3K27me3 (07-44) and anti-MMP-2 (AB19167) was purchased from Millipore (Temecula, CA). Anti-MMP-9 (ab3898) was purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG (NXA931) and donkey anti-rabbit IgG (NA934V) were obtained from GE healthcare (Buckinghamshire, UK). Control-siRNA (sc-37007) and Ezh2-siRNA (sc-35312) were purchased from Santa Cruz (Dallas, TX). Matrigel (354234) and BD Biocoat cell inserts (353097, 8 µm pore size) were purchased from BD Biosciences. EPZ-6438 (A-1623) was obtained from Active Biochemicals (Wan Chai, Hong Kong), and GSK126 (CT-GSK126) was purchased from ChemiTek (Indianapolis, IN). EPZ-6438 and GSK126 are Ezh2 inhibitors [39–43]. Sulforaphane was obtained from LKT Lab (St. Paul, MN), and delivered from a 1,000-fold stock dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide. Anti-procaspase 9 (95025), procaspase 8 (9746), procaspase 3 (9665), and anti-cleaved PARP (9541) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA).

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated using the RNAspin Mini Kit (GE Healthcare) and reverse transcribed using the Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). RNA (1 µg) was used for cDNA preparation. The Light Cycler 480 SYBR Green I Master mix (Roche Diagnostics) was used to measure mRNA level. Ezh2 mRNA level was detected and signals were normalized to the level of cyclophilin A mRNA. The following gene specific primers were used for detection of mRNA levels: Ezh2 (forward: 5′-GCA TCT ATT GCT GGC ACC ATC TGA, reverse: 5′-TTG TTA CCC TTG CGG GTT GCA T) and cyclophilin A (forward: 5′-CAT CTG CAC TGC CAA GAC TGA, reverse: 5′-TTC ATG CCT TCT TTC ACT TTGC).

Immunoblot

Equivalent amounts of protein were electrophoresed on denaturing and reducing 10% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 45 min and incubated with primary antibody at 1:1000 dilution in 5% nonfat dry milk. The blots were washed and then incubated with secondary antibody at a 1:5000 dilution for 2 h. Secondary antibody binding was visualized using ECL (Amersham) chemiluminescence detection technology.

Spheroid Formation Assay

A375 were maintained under attached conditions in growth media containing DMEM (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD) supplemented with 4.5 mg/ml D-glucose, 200 mM L-glutamine, 100 mg/ml sodium pyruvate, and 10% fetal calf serum. WM793 cells were maintained as attached monolayers in growth media including MCDB153 (M7403 Sigma, St. Louis, MO), L-15 (Invitrogen, Frederick, MD), 2% fetal calf serum, 5 µg/ml insulin (19278 Sigma), and 1.68 mM CaCl2. Both lines harbor the V600E B-Raf mutation [44,45]. For growth as spheroids, near-confluent monolayer cultures were dissociated with 0.05% trypsin and resuspended in spheroid media including DMEM/F12 (1:1) (DMT-10-090-CV, Mediatech Inc, Manassa, VA), 2% B27 serum-free supplement (17504-044, Invitrogen, Frederick, MD), 20 ng/ml EGF (E4269, Sigma, St. Louis), 0.4% bovine serum albumin (B4287, Sigma) and 4 µg/ml insulin. The cells were plated at 40,000 cells per 9.6 cm2 well in six well ultra-low attachment Costar cluster dishes (4371, Corning, Tewksbury, MA). Parallel cultures were plated in spheroid media on conventional plastic dishes for growth as monolayer cultures.

Electroporation

The day prior to electroporation A375 cells (150,000) were plated on 60 mm plates in spheroid media. For electroporation, 1.5 million cells were suspended in 100 µl of nucleofection reagent (VCA-1001, Walkersville, MD) containing either 3 µg of siRNA or 2 µg of plasmid DNA. The solution was gently mixed and then electroporated using the T-016 setting on the AMAXA electroporator followed by addition of one volume of pre-warmed spheroid media and plating in 60 mm cell culture plates in 3.8 ml of spheroid medium. For siRNA treatment, the cells were electroporated, permitted to recover for 72 h in culture and then re-electroporated with 3 µg of fresh siRNA before plating [46].

Invasion Assay

Matrigel (BD Biolabs) was diluted in 0.01M Tris– HCl containing 0.7% NaCl, filter sterilized, and 0.1 ml was added per BioCoat insert well and permitted to solidify. Cells were seeded at 25,000 per well in 100 µl of growth media containing 1% FCS. The lower chamber contained growth medium containing 10% FCS. After a 24 h incubation at 37°C, residuals cells were removed from the top and the membrane was rinsed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, and stained with 1 µg/ml DAPI for 10 min. The number of cells/10× field on the underside of the membrane were counted using an inverted fluorescent microscope.

Cell Migration Assay

Cells were plated at confluent density (2 million) in 10 cm dishes in spheroid medium. After attachment, a 10 µl pipette was used to create a wound in the monolayer, and the dishes were washed with PBS before addition of fresh medium. Images of wound were collected from 0–24 h to monitor wound closure [47,48].

Tumor Xenograft Studies

Monolayer and spheroid-derived cancer cells were dispersed with trypsin to produce a single cell suspension, and cells were resuspended in 200 µl of phosphate buffered saline containing 30% Matrigel. The mixture, containing 200,000 cells was injected subcutaneously into the two front flanks of NOD-scid-IL2 receptor gamma chain knockout mice (NSG mice) using a 26.5 gauge needle. Five mice were used per data point with two tumors per mouse. SFN was dissolved in water and 200 µl was delivered by oral gavage (10 µM/kg body weight) three times per week (M/W/F) beginning at the time of tumor cell injection. Tumor growth was monitored by measuring tumor diameter and calculating tumor volume using the formula, volume = 4/3π × (radius)3. Mice were euthanized by injecting 250 µl of a 2.5% stock of avertin per mouse followed by cervical dislocation, and tumor samples were harvested for morphological assessment, and preparation of sections and extracts. These experiments were reviewed and approved by the University of Maryland–Baltimore Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

RESULTS

Ezh2 Knockdown Impairs MCS Cell Spheroid Formation and Migration

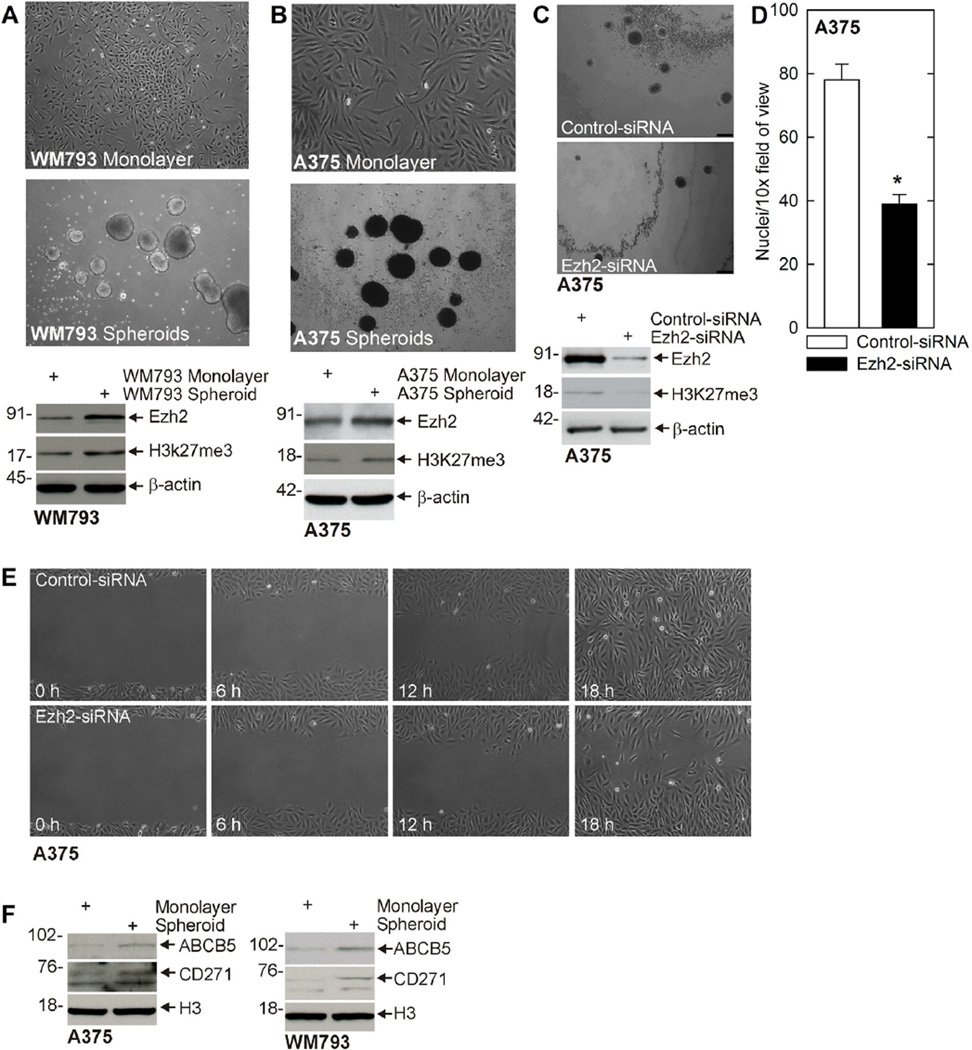

Cancer stem cells preferentially survive and form spheroids when plated in ultra-low attachment surfaces [49]. We assessed the ability of WM793 and A375 cells to form spheroids by plating 40,000 cells in spheroid growth medium in ultra-low attachment plates. Figure 1A and B shows that A375 cells form an average of 78 ± 5 spheroids (0.19% of the seeded cells), while WM793 cells formed 62 ± 6 spheroids (0.16% of seeded cells). Immunoblot of extracts prepared from spheroid and monolayer cultures reveals that Ezh2 is markedly elevated in the MCS cell (spheroid) population and that this is associated with increased H3K27me3 formation (Figure 1A and B). To determine if Ezh2 is necessary for spheroid formation, we monitored spheroid number in cells treated with control- or Ezh2-siRNA. As shown in Figure 1C, cells treated with Ezh2-siRNA express reduced levels of Ezh2 and display reduced H3K27me3 formation and form markedly fewer spheroids. Since cancer stem cells have been shown to possess enhanced migratory properties, we examined the impact of Ezh2 knockdown on MCS cell ability to invade matrigel (Figure 1D) and migrate to close a scratch wound (Figure 1E). These findings show that loss of Ezh2 reduces MCS cell invasion and migration. To assess the stem cell status of the monolayer versus spheroid cells, we assayed for expression of two stem cell markers that are frequently highly expressed in melanoma cancer stem cells, ABCB5 and CD271 [8]. As shown in Figure 1F, spheroid-derived cultures are enriched in both markers, a finding consistent with a stem cell phenotype.

Figure 1.

Ezh2 is enriched in MCS cells and is required for spheroid formation and migration. (A/B) MCS cells are enriched for expression of Ezh2. WM793 and A375 cells were grown in spheroid medium in monolayer culture (non-stem cancer cells) or as unattached spheroids (MCS cells) for 10 d. Extracts were prepared for immunoblot detection of Ezh2. (C) A375 cells were electroporated with control- or Ezh2-shRNA and 40,000 cells were plated in 35 mm dishes to monitor spheroid number. Extracts were prepared for immunoblot detection of Ezh2 to confirm knockdown. Bar = 125 µm. (D) Ezh2 knockdown reduces cell matrigel invasion. A375-derived MCS cells were electroporated with control- or Ezh2-siRNA and 25,000 cells were seeded atop matrigel in Millicell chambers and migration to the lower chamber was monitored at 24 h by DAPI staining. The values are mean ± SEM. The asterisk indicates a significant difference, n = 4, P < 0.005. (E) A375 cells were electroporated with control- or Ezh2-shRNA and then plated at confluent density. Wounds were created by scraping with a pipette tip and wound closure was monitored from 0 to 18 h. Similar results were observed in each of three experiments. (F) Spheroid cultures are enriched in MCS cell markers. Extracts were prepared from monolayer and spheroid cultures of A375 and WM793 cells and assayed for expression of ABCB5 and CD271.

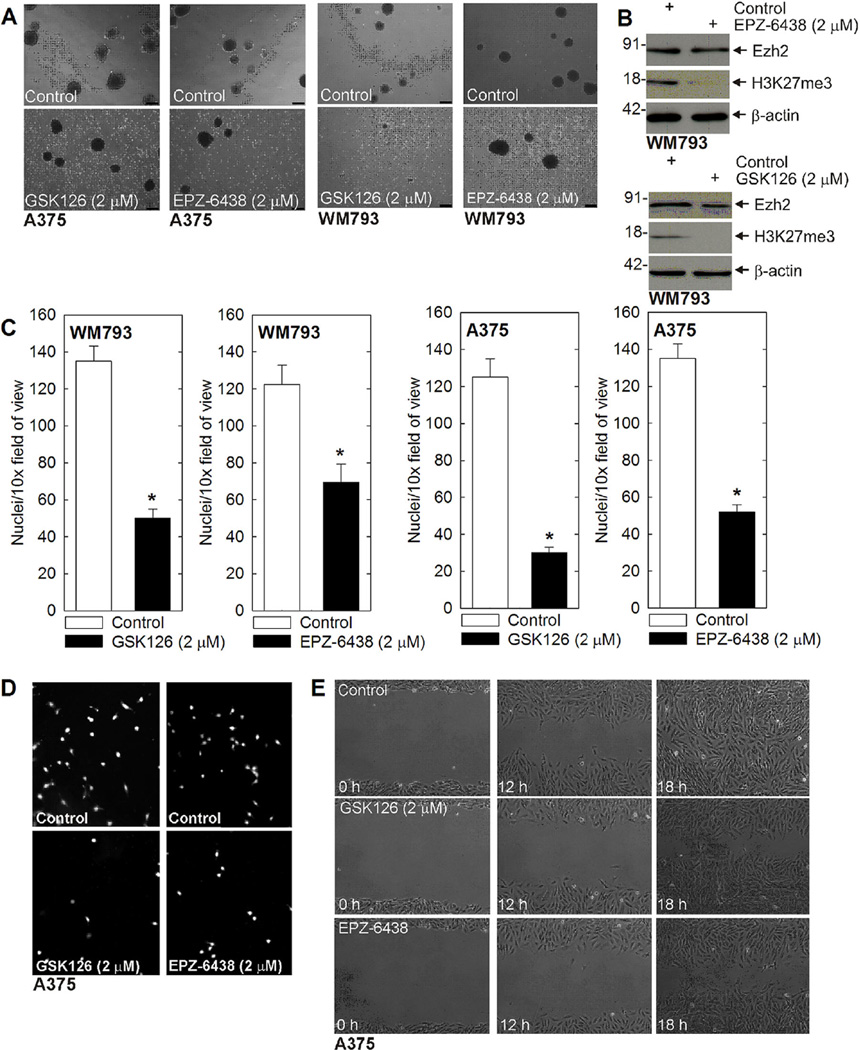

We next looked at the impact of Ezh2 inhibitors on MCS cells. GSK126 and EPZ-6438 are agents that inhibit Ezh2 catalytic activity. We monitored the impact of these compounds on spheroid formation, and cell invasion and migration. Figure 2A shows that treatment with each agent reduces WM793 and A375 cell spheroid formation and leads to accumulation of cell debris. Figure 2B confirms that treatment reduces Ezh2 activity as measured by suppression of H3K27me3 formation. We next measured the impact on cell ability to invadematrigel. MCS cells were plated on matrigel and migration was monitored over 24 h. Figure 2C shows that treatment with 2 µM GSK126 or EPZ-6438 reduces MCS cell invasion, and Figure 2D are images showing the reduced invasion. As a third measure of ability of these agents to modify MCS cell behavior, we monitored impact on cell migration using the wound closure assay. As shown in Figure 2E, treatment with GSK126 or EPZ-6438 reduces wound closure, suggesting that Ezh2 activity is required for cell migration. We note that these changes in invasion and migration are not due to changes in cell proliferation, as cell proliferation is not suppressed at 24h after these treatments (not shown).

Figure 2.

Ezh2 inhibitors suppress MCS cell spheroid survival, invasion, and migration. (A) A375 or WM793 cells (40,000) were plated in non-adherent six well dishes, grown for 7 d in spheroid medium, and then treated with GSK126 or EPZ-6438 for 48 h. Bars = 125 µm. (B) Inhibitor treatment of spheroids is associated with a reduction in Ezh2 function as measured by reduced H3K27me3 formation. Spheroids were harvested from the experiment in panel A for immunoblot. (C/D) Ezh2 inhibitors reduce MCS cell invasion. A375- or WM793-derived MCS cells (25,000) cells were seeded on matrigel in Millicell chambers and then treated with GSK126 or EPZ-6438. At 24 h, the chambers were harvested, rinsed, and cells that had migrated through to the membrane inner surface were visualized using DAPI. The values are mean ± SEM. The asterisks indicate significant changes, n = 4, P < 0.005. The images show DAPI detection of migrated cell nuclei for a typical invasion experiment. (E) A375 cells were plated at confluent density in 100 mm dishes and scratch wounds were created using a pipette tip followed by treatment with no agent, GSK126 or EPZ-6438. Wound width was monitored for 0–18 h. Similar results were observed for WM793 cells (not shown) in each of three experiments.

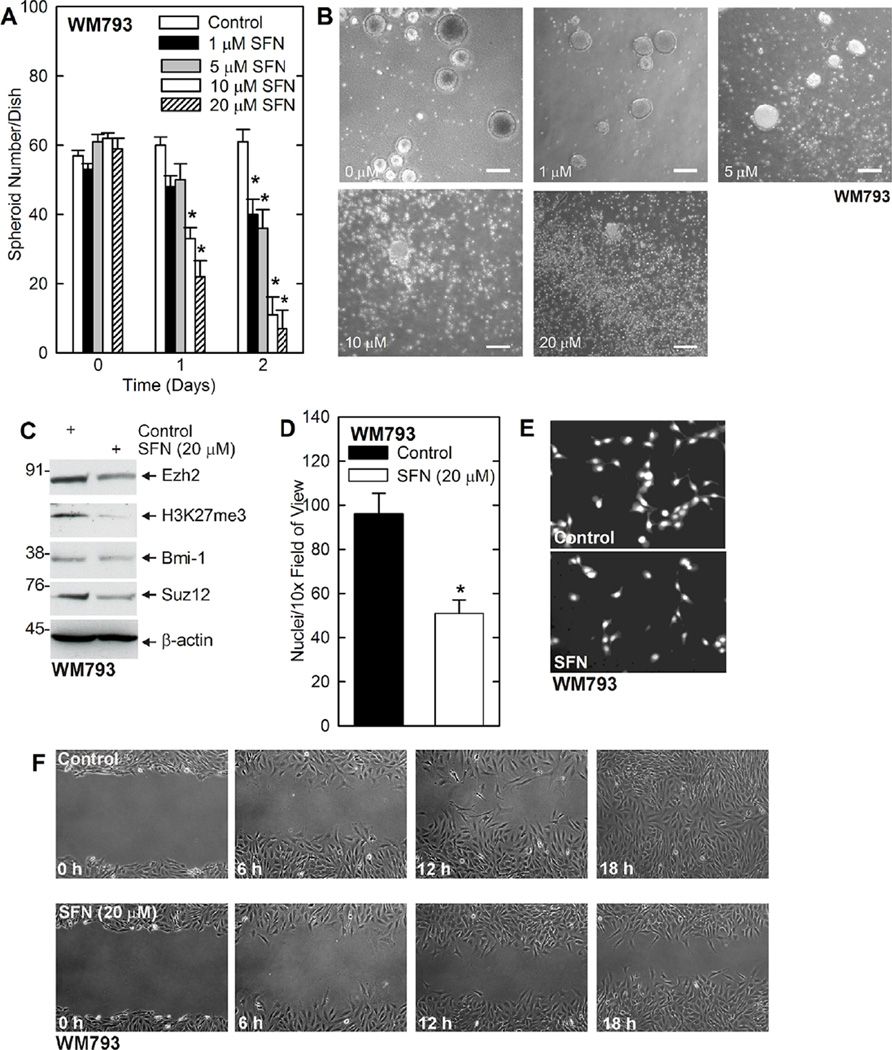

Sulforaphane Impact on MCS Cell Function and Role of Ezh2

We have previously shown that sulforaphane (SFN), a cancer prevention agent derived from cruciferous vegetables, suppresses Ezh2 function in epidermal squamous cell carcinoma [50]. We therefore examined the impact of SFN on MCS cell function. Spheroids were permitted to form for 8 d followed by treatment with 0–20 µMSFN. Figure 3A shows that treatment with SFN efficiently reduces WM793 cell spheroid formation which is associated with accumulation of cell debris (Figure 3B). Figure 3C shows that the SFN-dependent reduction in MCS cell spheroid survival is associated with reduced Ezh2 level and activity. The level of the Bmi-1 and Suz12 polycomb proteins are also reduced. Half-maximal suppression of spheroid formation was observed at around 5 µM SFN. In addition, SFN reduces WM793 cell invasion, as measured by ability to migrate through matrigel (Figure 3D and E), and also reduces MCS cell ability to close a scratch wound (Figure 3F).

Figure 3.

SFN treatment causes fragmentation of preformed MCS cell spheroids and inhibits MCS cell invasion and migration. (A/B) WM793 cells (40,000) were plated in spheroid medium in non-adherent six well plates. Spheroids were grown for 7 d, treated for 0–48h with 0–20 µM SFN and spheroid numbers were counted. The values are mean ± SEM. The asterisks indicate specific changes compared to control, n = 3, P < 0.005. Representative spheroid images following a 2 d treatment with 0–20 µM SFN. Bars = 125 µm. (C) WM793-dervied spheroids were treated for 48h with 0 or 20 µM SFN prior to preparation of extracts to monitor the level of the indicated epitopes. (D/E) WM793 cells (25,000) were seeded on matrigel in six Millicell chambers per group, and treated with 0 or 20 µM SFN. After 24 h, the chambers were harvested, washed, and cells on the inner membrane surface were stained with DAPI and counted. The values are mean ± SEM. The asterisk indicates a significant change, n = 3, P < 0.005. Also shown is a typical image of DAPI stained migrated cells. (F) WM793 cells (2 million) were permitted to form a confluent monolayer in 100 mm dishes and then scratched with a pipette tip followed by immediate treatment with 0 or 20 µM SFN. Wound width was monitored for 0–18 h. This experiment is representative of three separate experiments.

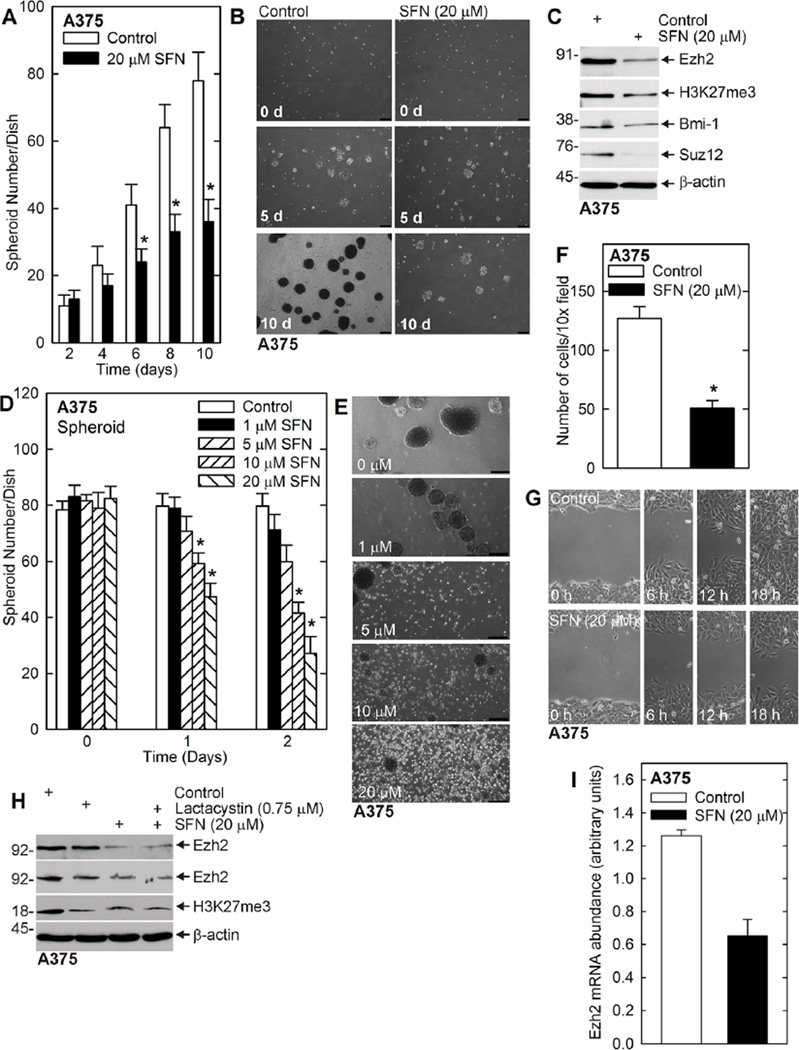

We also examined the impact of SFN on MCS cells derived from A375 cells. A375 cells were seeded in spheroid growth conditions in ultra-low attachment plates followed by treatment with 20 µM SFN. Figure 4A and B shows that SFN treatment reduces spheroid formation and that this is associated with spheroid fragmentation. Figure 4C shows that SFN treatment is associated with a reduction in Ezh2 level and H3K27me3 formation, and also reduced expression of Bmi-1 and Suz12. In a parallel experiment, the impact of SFN on survival of pre-formed spheroids was examined. These studies, shown in Figure 4D and E, indicate that SFN produces a half-maximal reduction in spheroid number at 10 µM. In addition, SFN treatment reduces MCS cell invasion (Figure 4F) and migration (Figure 4G). We note that the decrease in migration and invasion in SFN-treated cells is not due to decreased proliferation, as treatment with 20 µMSFN for 24 h does not reduce cell number in a growth assay (not shown).

Figure 4.

SFN treatment reduces A375 cell spheroid formation and survival, and inhibits migration. (A/B) SFN treatment reduces spheroid growth. A375 cells (40,000) were seeded in ultra-low attachment wells in six well dishes. Spheroid growth was monitored in the presence of 0 or 20 µM SFN. The values are mean ± SEM. The asterisks indicate a significant change, n = 3, P < 0.005. The images show the reduction in spheroid number in SFN treated cultures as compared to control. (C) SFN treatment reduces Ezh2 level and activity in A375 cells. Ten day spheroids from panel A were harvested and proteins were assayed by immunoblot. (D/E) SFN treatment reduces spheroid number and integrity. A375 cell (40,000) were plated in ultra-low attachment wells in six well dishes, and grown for 8 d in spheroid medium, prior to initiation of 0–20 µMSFN treatment for 0–48 h. The values are mean ± SEM. The asterisk indicates a significant change, n = 3, P < 0.005. Images show that fragmentation of the spheroids in response to SFN treatment. The white spots are single cells that have been released from existing spheroid during SFN-dependent spheroid dissolution. (F) MCS cells (25,000), derived from A375 cells, were seeded on Matrigel at six Millicell chambers/group and treated with 0 or 20 µM SFN. After 24h, cells that had migrated through to the membrane inner surface were imaged using DAPI. The values are mean ± SEM. The asterisks indicate significant change, n = 4, P < 0.005. (G) A375 cells (2 million) were permitted to form confluent monolayers in 100 mm dishes in spheroid medium. Scratch wounds were created followed by treatment with 0 or 20 µM SFN and wound width was monitored over 0–18 h. Similar results were observed in each of three experiments. (H) A375 cells were treated with SFN in the presence or absence of lactacystin and after 48 h cell extracts were prepared for assay of Ezh2 and H3K27me3. Similar results were observed in three experiments. (I) SFN significantly reduces Ezh2 mRNA level. A375 cells were grown as spheroids and extracts were prepared for assay of Ezh2 mRNA by qRT-PCR. The values are mean ± SEM, n = 3, P < 0.005.

Previous studies have shown that SFN, and other cancer prevention agents, can suppress Ezh2 level via proteasome-dependent mechanisms [50–52]. We therefore assessed whether lactacystin, a proteasome inhibitor, blocked the SFN-dependent loss of Ezh2 in A375 cells. Figure 4H shows that SFN reduces Ezh2 level and H3K27me3 formation, but this is not reversed by lactacystin. Instead, as shown in Figure 4I, SFN treatment reduces Ezh2 mRNA level, suggesting that SFN suppression of Ezh2 gene transcription may reduce Ezh2 level.

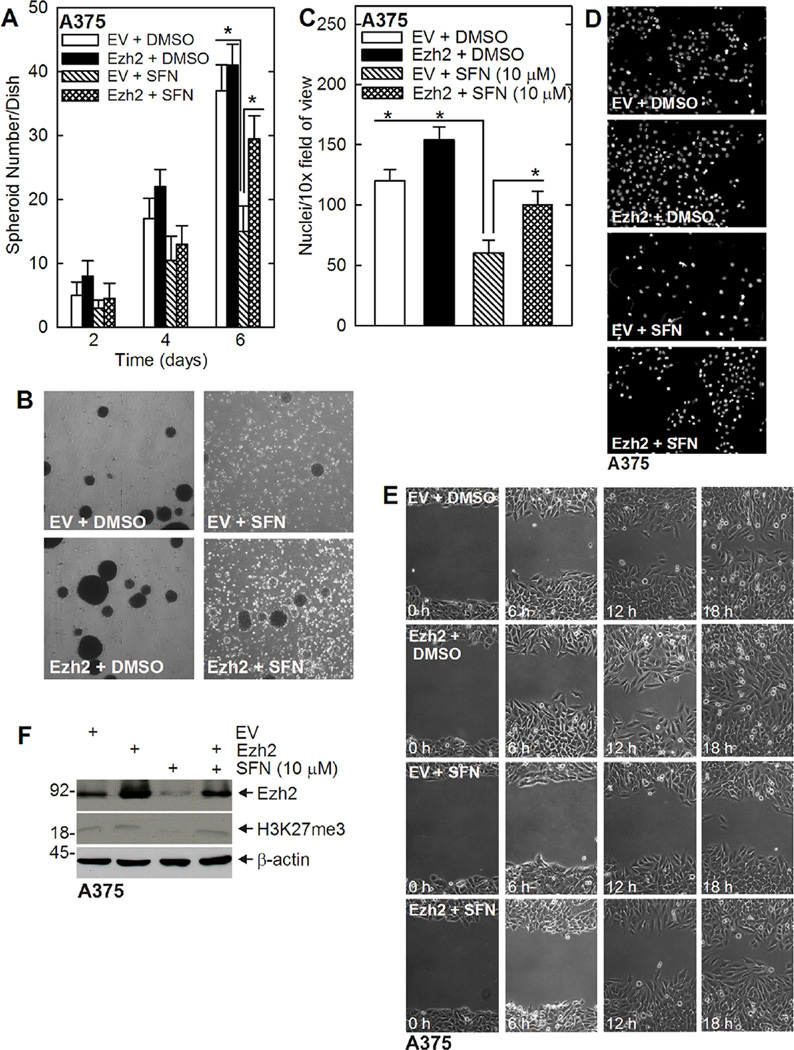

Ezh2 Overexpression Protects Against SFN

We propose that a reduction in Ezh2 (Figure 3C) is required for SFN suppression of ECS cell survival. This predicts that Ezh2 overexpression should reverse SFN action. To test this, we electroporated A375 cells with empty (EV) or Ezh2 expression plasmid and then challenged with SFN. Figure 5A and B shows that Ezh2 partially reverses the SFN-dependent suppression of spheroid formation. The cells were electroporated with EV or Ezh2 vector, seeded under spheroid growth conditions, and spheroid number was monitored at 2, 4, and 6 d. At day 6, there is a significant decrease in spheroid number in the EV + SFN group, and this reduction is partially reversed in the Ezh2 + SFN group. We next monitored the impact of SFN on A375 cell invasion and migration. Figure 5C and D shows that Ezh2 expression increases matrigel invasion in control and SFN-treated cells. Figure 5E shows that Ezh2 expression partially reverses SFN suppression of ECS cell wound closure. Figure 5F confirms the reduction in Ezh2 level and H3K27me3 formation in SFN-treated cells and shows that Ezh2 expression plasmid restores both Ezh2 level and H3K27me3 formation. Thus, Ezh2 is able to partially reverse the SFN suppression of spheroid formation, matrigel invasion, and cell migration.

Figure 5.

Loss of Ezh2 is required for SFN action. (A/B) A375 cells were electroporated with empty (EV)- or Ezh2-encoding plasmid and plated in 35 mm ultra-low attachment dishes in spheroid medium and then treated, beginning at the time of plating, with 0 or 10 µM SFN. Spheroid formation was monitored from 0 to 6 d. The values are mean ± SEM. The double-asterisks indicate a significant reduction in in the EV + SFN group as compared to the EV + DMSO and Ezh2 + DMSO groups, n = 3, P < 0.005. The single asterisk indicates an increase in the Ezh2 + SFN group as compared to EV + SFN group, n = 3, P <0.005. The image shows the typical appearance of the spheroids in these experiments. Note the accumulation of single cells and cell debris in the SFN-treated groups and the partial restoration of spheroid formation in the Ezh2 + SFN group. (C/D) Ezh2, SFN and MCS cell invasion. A375 cells were electroporated with empty (EV) or Ezh2-encoding vector and then 25,000 cells were plated on matrigel in Millicell chambers simultaneous with treatment with 0 or 20 µMSFN. Migrated cells were counted after 24 h. The double-asterisks indicate a significant reduction in in the EV + SFN group as compared to the EV + DMSO and Ezh2 + DMSO groups, n = 3, P < 0.005. The single asterisk indicates an increase in the Ezh2 + SFN group as compared to EV + SFN group, n = 3, P < 0.005. The images show a typical level of migration. (E) Ezh2, SFN, and MCS cell migration. A375 cells (2 million) were permitted to form confluent monolayers in 100 mm dishes in spheroid medium. Scratch wounds were created followed by treatment with 0 or 20 µM SFN and wound width was monitored over 0–18 h. Similar results were observed in each of three experiments. (F) Ezh2 expression in electroporated cells. A375 cells were electroporated with 3 µg of empty (EV) or Ezh2-encoding vector. After 24 h, the cells were treated with 0 or 10 µM SFN for 48 h and Ezh2 and H3K27me3 level were monitored after an additional 48 h.

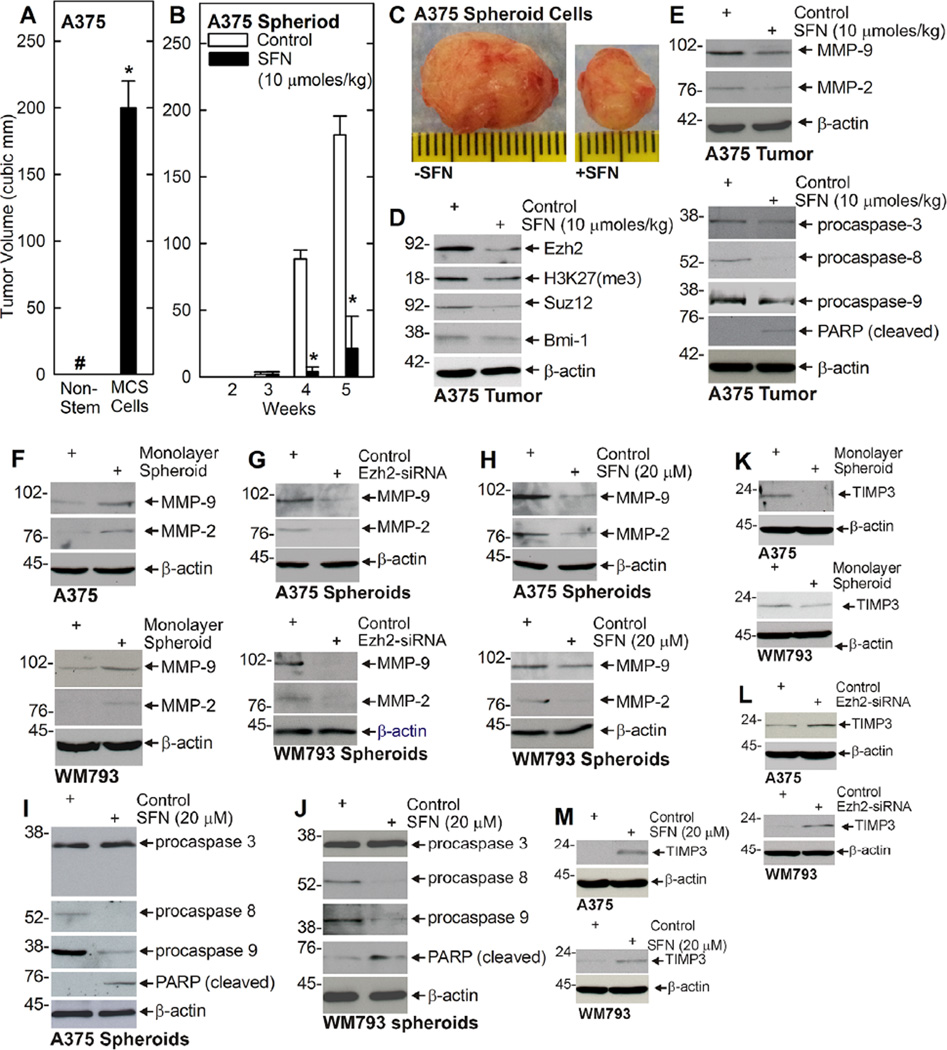

SFN Treatment Suppresses Tumor Formation

We next examined the ability of non-stem cancer cells (derived from monolayer cultures) and MCS cells (selected as spheroids on ultra-low attachment dishes) to form tumors in NSG mice. Figure 6A shows that MCS cells form large and aggressive tumors. Interestingly, non-stem cancer cells do not form palpable tumors as designated by the # symbol (Figure 6A). To determine the impact of SFN treatment on MCS cell tumor formation, we injected 100,000 MCS cells into each front flank of NSG mice and monitored tumor formation with SFN treatment initiated at the time of tumor cell injection. Figure 6B shows that tumors first appear at 4wk post-injection and that SFN treatment markedly reduces tumor formation at 4 and 6 wk. Figure 6Cshows the difference in tumor size and appearance following SFN treatment for 6wk. Moreover, SFN treatment is associated with reduced Ezh2 level and H3K27me3 formation, reduced matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-9, MMP-2) level, and enhanced procaspase 8, procaspase 9, and PARP cleavage (Figure 6D and E).

Figure 6.

SFN inhibits MCS cell tumor formation. (A) MCS cells, but not non-stem cancer cells form tumors. One hundred thousand A375 monolayer (non-stem cancer cells) or spheroid cells (MCS cells) were injected into each front flank of NSG mice and tumor formation was monitored for 5wk. The tumor volume was calculated as 4/3π × (diameter/2)3 using values derived from caliper measurements. The pound sign indicates tumors were not palpable for the non-stem cancer cells (only flat plagues that did not grow were detected). The values are mean ± SEM and the asterisk indicates significant differences in tumor size (n = 6, P < 0.005). (B/C) A375 cell-derived MCS cells (100,000) were injected into each front flank in NSG mice. At 1 d post injection, cells were treated with 0 (Control) or 10 µmoles SFN/kg body weight delivered in 200 µl by gavage and treatment was continued three times per week for the duration of the experiment. The values are mean ± SEM and asterisks indicate significant differences in tumor size (n = 6, P < 0.005). The images represent appearance and size of typical control and SFN-treated tumors harvested on week 5. (D) SFN reduces Ezh2 level and H2K27me3 formation in tumors. Extracts were prepared from 5wk control and SFN-treated tumors for immunoblot detection of Ezh2 and H3K27me3. Similar findings were observed in each of three experiments. Suz12 and Bmi-1 levels are also reduced. (E) SFN treatment suppresses MMP level and enhances apoptosis in A375 tumors. Extracts were prepared from the tumors described in panels B/C and assayed for expression of the indicated proteins. (F) Matrix metalloproteinases are elevated in MCS cells. Cells were grown for 8 d as monolayers (non-stem cancer cells) or spheroids (MCS cells) and then assayed for presence of the indicated proteins. (G/H) Ezh2 knockdown or SFN treatment reduces matrix metalloproteinase expression. MCS cells were grown as spheroids for 8 d and then treated with 0 or 20 µM SFN for 48 h. Extracts were prepared for detection of the indicated markers. (I/J) SFN treatment increases procaspase and PARP cleavage. MCS cells were grown as spheroids for 8 d and then treated with 0 or 20 µM SFN for 48 h. Extracts were prepared for detection of the indicated markers. (K/L/M) TIMP3 is suppressed in MCS cells and increased in Ezh2 knockdown and SFN treated MCS cells. (K) MCS cells were grown as monolayers or 8 d spheroids and extracts were prepared for detection of TIMP3. (L) Cells were electroporated with 3 µg of control- or Ezh2-siRNA and grown as spheroids for 5 d before extract preparation for immunoblot. (M) Eight day spheroids were treated with 0 or 20 mM SFN for 48 h and extracts were prepared for detection of TIMP3.

To assess whether we could demonstrate importance of these markers in cultured MCS cells, we compared expression in non-stem cancer cells (monolayer) and MCS cells and also the impact of SFN treatment on expression. Figure 6F shows that MMP-9 and MMP-2 levels are elevated in MCS cells (spheroids) derived from A375 and WM793 cells. In addition, Ezh2 knockdown (Figure 6G) or SFN treatment (Figure 6H) reduced MCS cell MMP-9 and MMP-2 level, and increases procaspase 8 and 9, and PARP cleavage (Figure 6I and J). In contrast, procaspase-3 level was not altered (Figure 6I and J). TIMP3 is a metalloproteinase inhibitor that known to be suppressed by Ezh2. Figure 6K shows that TIMP3 is reduced in MCS cells (spheroid), and that MCS cell TIMP3 level is increased by Ezh2 knockdown (Figure 6L or SFN treatment (Figure 6M).

DISCUSSION

Ezh2 is Required for MCS Cell Survival

The cancer stem cell population comprises cells that undergo self-renewal, display enhanced invasion, and migration potential, and form tumors with high efficiency when injected at limiting dilutions in immunocompromised mice [53,54]. Moreover, cancer stem cells often survive conventional therapy and subsequently form highly aggressive and invasive tumors [53]. Thus, development of prevention and treatment strategies that target cancer stem cells is a priority. We have focused on the polycomb proteins as potential stem cell-enriched cancer prevention and treatment targets [15,46,50,52,55,56]. The polycomb proteins function as two distinct complexes that act sequentially on chromatin. Polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) and polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) [9] suppress gene expression via covalent modification of selected histones [9–14]. Ezh2 is a PRC2 complex component that trimethylates lysine 27 of histone H3 (H3K27me3) [13,57]. This is the first step in gene silencing. H3K27me3 then serves as a binding site for the chromodomain of the CBX protein of the PRC1 complex which anchors the PRC1 complex to the chromatin [57]. Ring1B, is the key activity of the PRC1 complex and it ubiquitinates histone H2A at lysine 119 [10,57]. The sequential trimethylation and ubiquitination events result in chromatin condensation leading to silencing of tumor suppressor gene expression [9,13].

We explored the role of Ezh2 in MCS cells isolated fromWM793 and A375 melanoma cells. We show that growth of these cells on ultra-low attachment surfaces selects for a limited subpopulation of spheroid-forming cells. This percentage is 0.19% for A375 cells and 0.16% for WM793 cells, and is comparable to previous estimates in squamous cell carcinoma [53]. Our strategy has been to identify proteins that are elevated in level or activity in cancer stem cells as potential survival proteins and cancer prevention/therapy targets [46–48,53]. In this context, we show that these cells are enriched for expression of Ezh2 and that this is associated with enhanced Ezh2 biological activity as measured by increased H3K27me3 formation. Ezh2 has been shown to be elevated in and required for survival of other cancer stem cell types [46]. We show that Ezh2 knockdown reduces H3K27me3 formation and MCS cell spheroid formation, invasion, and migration. The Ezh2 requirement for optimal MCS cell survival is observed for both WM793 and A375 cell-derived MCS cells.

Pharmacologic Inhibition of Ezh2 Activity

We also examined the effect of small molecule inhibitors of Ezh2 activity on MCS cell function. GSK126 [39] and EPZ-6438 [41–43] are selective competitive inhibitors of S-adenosyl-methionine-dependent Ezh2 methyltransferase activity. An important finding is that these agents suppress the aggressive MCS cell phenotype. This includes inhibition of MCS cell spheroid formation and maintenance, invasion (through matrigel), and migration. Treatment is associated with reduced catalytic activity as evidenced by the reduction in H3K27me3 formation, but Ezh2 level is not reduced.

SFN Treatment Reduces MCS Cell Survival

SFN is a diet-derived natural agent, present in cruciferous vegetables, that suppresses cancer formation in several systems [29,50,58–62]. Previous studies suggest that SFN suppresses survival of melanoma cancer cells via mechanisms that involve induction of apoptosis [34,35]. However, the impact on MCS cells has not been studied. We provide evidence that treatment with low levels of SFN (1–20 µM) suppresses MCS cell spheroid formation, and promotes spheroid destruction. This is associated with the loss of Ezh2 and reduced H3K27me3 formation, as well as loss of additional polycomb proteins (Suz12 and Bmi-1). We have not checked the impact on other polycomb group proteins, but it has been previously reported that modulating Ezh2 level alters the level of other polycomb proteins in a non-predictable cell-type specific manner [53]. SFN treatment reduces MCS cell invasion through matrigel and also inhibits MCS cell migration. These findings suggest that SFN is a candidate agent for prevention/treatment of melanoma via suppression of MCS cell function.

Ezh2 Protects MCS Cells From SFN Treatment

Overexpression studies confirm that Ezh2 is an important MCS cell survival protein and SFN target, as maintaining Ezh2 expression partially protects MCS cells against SFN challenge. Maintaining Ezh2 level protects MCS cells against SFN suppression of spheroid formation, cell invasion, and cell migration. This is consistent with a recent study showing that polycomb group expression attenuates SFN-dependent apoptosis in epidermal squamous cell carcinoma cells [50]. A previous study, using non-stem melanoma cells, showed that Ezh2 loss reduces cell proliferation, restores cellular senescence, enhances p21Cip1 expression, and inhibits melanoma cell xenograft growth [25]. We now study the role of Ezh2 in MCS cells and show that is it markedly upregulated in MCS cells (relative to non-stem cancer cells) and that reducing Ezh2 level reduces MCS cell spheroid formation migration and invasion. Thus, Ezh2 appears to be enriched in MCS cells and to have a role in maintaining this cell population.

SFN Suppresses MCS Cell Tumor Formation

We also examined the effects of SFN treatment on MCS cell-dependent tumor formation using A375 cell-derived MCS cells. A remarkable finding is that subcutaneous injection of 100,000 non-stem melanoma cells into the front flanks of NSG mice does not result in tumor formation. Instead, the cells remainas a small plaque that does not change in size. This is in contrast to MCS cells which form well-circumscribed, rapidly growing, and aggressive tumors. This provides evidence that MCS cells have greatly enhanced tumor formation potential. We further show that SFN treatment reduces tumor formation, and that this is associated with reduced Ezh2, Suz12, andBmi-1 levels, and reduced H3K27me3 formation. In the context of our cell culture findings, which show that SFN reduces Ezh2 andH2K27me3 formation, these in vivo findings suggest that SFN reduction of tumor formation may require a reduction in Ezh2 level and activity.

Impact of SFN on Downstream Events

We also examined the impact of SFN treatment or Ezh2 knockdown on matrix metalloproteinase level. The balance between matrix metalloproteinases, and metalloproteinase inhibitors, in tumors, defines the net level of metalloproteinase activity. High metalloproteinase activity is associated with increased invasion and metastasis [63]. We observed increased MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels in MCS cells as compared to non-stem cancer cells. As SFN reduces MMP expression in several cancer models [36,64], we examined the impact of SFN treatment on metalloproteinase level in MCS cell-derived tumors. We found that SFN treatment reduces MMP-2 and MMP-9 levels, a finding that was confirmed in cultured MCS cells. This reduction in MMP expression is associated with reduced tumor formation. We also observed that Ezh2 knockdown in cultured MCS cells reduces MMP-9 and MMP-2 level, suggesting that Ezh2 exerts control of these pro-cancer activities. Metalloproteinase inhibitors, such as TIMP3, interact with and inhibit metalloproteinases [65]. It is interesting that in other models increased Ezh2 expression/activity is associated with suppression of TIMP3 expression [66,67]. We confirmed that TIMP3 is reduced in MCS cells, as compared to non-stem cancer cells and that TIMP3 levels is increased by treatment with SFN or Ezh2 knockdown. These findings are consistent with enhanced MMP activity in MCS cells and suppression of MMP activity following SFN treatment.

We also observed enhanced levels of cleaved caspase and PARP in SFN treated cells. The fact that the cells are undergoing apoptosis is consistent with previous studies in Bowes, SK-Mel-28, and B16F-10 melanoma cells which indicate that SFN induces apoptosis [34,35]. However, the present study extends these findings to melanoma cancer stem cells. Finally, unlike some other model systems [50–52], SFN does not reduce Ezh2 via a proteasome-dependent mechanism, but does reduce Ezh2 mRNA.

Based on these studies, we propose that SFN treatment of MCS cells results in reduced Ezh2 level and activity and that this is associated with reduced matrix metalloproteinase level and enhanced apoptosis. We further propose that SFN is a candidate agent for the prevention and treatment of melanoma that may selectively impact MCS cells, by reducing the level of MCS cell survival proteins, including Ezh2.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 CA131064 and R01 CA184027 to RLE, and by a pilot grant from the Greenebaum Cancer Center.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors indicate no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wagle N, Emery C, Berger MF, et al. Dissecting therapeutic resistance to RAF inhibition in melanoma by tumor genomic profiling. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3085–3096. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ilieva KM, Correa I, Josephs DH, et al. Effects of BRAF mutations and BRAF inhibition on immune responses to melanoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;12:2769–2783. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spagnolo F, Ghiorzo P, Queirolo P. Overcoming resistance to BRAF inhibition in BRAF-mutated metastatic melanoma. Oncotarget. 2014;5:10206–10221. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spagnolo F, Ghiorzo P, Orgiano L, et al. BRAF-mutant melanoma: Treatment approaches, resistance mechanisms, and diagnostic strategies. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:157–168. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S39096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Crish JF, Howard JM, Zaim TM, Murthy S, Eckert RL. Tissue-specific and differentiation-appropriate expression of the human involucrin gene in transgenic mice: An abnormal epidermal phenotype. Differentiation. 1993;53:191–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1993.tb00708.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wegner M, Drolet DW, Rosenfeld MG. POU-domain proteins: Structure and function of developmental regulators. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1993;5:488–498. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(93)90015-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quintana E, Shackleton M, Sabel MS, Fullen DR, Johnson TM, Morrison SJ. Efficient tumor formation by single human melanoma cells. Nature. 2008;456:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature07567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy GF, Wilson BJ, Girouard SD, Frank NY, Frank MH. Stem cells and targeted approaches to melanoma cure. Mol Aspects Med. 2014;39:33–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jacobs JJ, van LM. Polycomb repression: From cellular memory to cellular proliferation and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1602:151–161. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(02)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sparmann A, van LM. Polycomb silencers control cell fate, development, and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:846–856. doi: 10.1038/nrc1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vaissiere T, Sawan C, Herceg Z. Epigenetic interplay between histone modifications and DNA methylation in gene silencing. Mutat Res. 2008;659:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobs JJ, Kieboom K, Marino S, DePinho RA, van LM. The oncogene and Polycomb-group gene bmi-1 regulates cell proliferation and senescence through the ink4a locus. Nature. 1999;397:164–168. doi: 10.1038/16476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orlando V. Polycomb, epigenomes, and control of cell identity. Cell. 2003;112:599–606. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Valk-Lingbeek ME, Bruggeman SW, van Lohuizen M. Stem cells and cancer: The polycomb connection. Cell. 2004;118:409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eckert RL, Adhikary G, Rorke EA, Chew YC, Balasubramanian S. Polycomb group proteins are key regulators of keratinocyte function. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:295–301. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crea F, Fornaro L, Bocci G, et al. EZH2 inhibition: Targeting the crossroad of tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2012;31:753–761. doi: 10.1007/s10555-012-9387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutat Res. 2008;647:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yamaguchi H, Hung MC. Regulation and role of EZH2 in cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2014;46:209–222. doi: 10.4143/crt.2014.46.3.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang X, Sun Y, Han S, Zhu W, Zhang H, Lian S. MiR-203 inhibits melanoma invasive and proliferative abilities by targeting the polycomb group gene BMI1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;456:361–366. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang JM, Hornyak TJ. Polycomb group proteins—Epigenetic repressors with emerging roles in melanocytes and melanoma. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015;28:330–339. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo C, Merz PR, Chen Y, et al. MiR-101 inhibits melanoma cell invasion and proliferation by targeting MITF and EZH2. Cancer Lett. 2013;341:240–247. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2013.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo C, Tetteh PW, Merz PR, et al. miR-137 inhibits the invasion of melanoma cells through downregulation of multiple oncogenic target genes. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:768–775. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu S, Tetzlaff MT, Cui R, Xu X. miR-200c inhibits melanoma progression and drug resistance through down-regulation of BMI-1. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:1823–1835. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asangani IA, Harms PW, Dodson L, et al. Genetic and epigenetic loss of microRNA-31 leads to feed-forward expression of EZH2 in melanoma. Oncotarget. 2012;3:1011–1025. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fan T, Jiang S, Chung N, et al. EZH2-dependent suppression of a cellular senescence phenotype in melanoma cells by inhibition of p21/CDKN1A expression. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9:418–429. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-10-0511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manning CS, Hooper S, Sahai EA. Intravital imaging of SRF and Notch signalling identifies a key role for EZH2 in invasive melanoma cells. Oncogene. 2015;33:4320–4332. doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tiffen J, Gallagher SJ, Hersey P. EZH2: An emerging role in melanoma biology and strategies for targeted therapy. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015;28:21–30. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kampilafkos P, Melachrinou M, Kefalopoulou Z, Lakoumentas J, Sotiropoulou-Bonikou G. Epigenetic modifications in cutaneous malignant melanoma: EZH2, H3K4me2, and H3K27me3 immunohistochemical expression is enhanced at the invasion front of the tumor. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:138–144. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31828a2d54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Clarke JD, Dashwood RH, Ho E. Multi-targeted prevention of cancer by sulforaphane. Cancer Lett. 2008;269:291–304. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Egner PA, Chen JG, Zarth AT, et al. Rapid and sustainable detoxication of airborne pollutants by broccoli sprout beverage: Results of a randomized clinical trial in China. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:813–823. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-14-0103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho E, Clarke JD, Dashwood RH. Dietary sulforaphane, a histone deacetylase inhibitor for cancer prevention. J Nutr. 2009;139:2393–2396. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.113332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh SV, Warin R, Xiao D, et al. Sulforaphane inhibits prostate carcinogenesis and pulmonary metastasis in TRAMP mice in association with increased cytotoxicity of natural killer cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2117–2125. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Y, Zhang T, Li X, et al. Kinetics of sulforaphane in mice after consumption of sulforaphane-enriched broccoli sprout preparation. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57:2128–2136. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201300210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudolf K, Cervinka M, Rudolf E. Sulforaphane-induced apoptosis involves p53 and p38 in melanoma cells. Apoptosis. 2014;19:734–747. doi: 10.1007/s10495-013-0959-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hamsa TP, Thejass P, Kuttan G. Induction of apoptosis by sulforaphane in highly metastatic B16F-10 melanoma cells. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2011;34:332–340. doi: 10.3109/01480545.2010.538694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pradhan SJ, Mishra R, Sharma P, Kundu GC. Quercetin and sulforaphane in combination suppress the progression of melanoma through the down-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Exp Ther Med. 2010;1:915–920. doi: 10.3892/etm.2010.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thejass P, Kuttan G. Modulation of cell-mediated immune response in B16F-10 melanoma-induced metastatic tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice by sulforaphane. Immunopharmacol Immunotoxicol. 2007;29:173–186. doi: 10.1080/08923970701511728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chinembiri TN, du Plessis LH, Gerber M, Hamman JH, du PJ. Review of natural compounds for potential skin cancer treatment. Molecules. 2014;19:11679–11721. doi: 10.3390/molecules190811679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCabe MT, Ott HM, Ganji G, et al. EZH2 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy for lymphoma with EZH2-activating mutations. Nature. 2012;492:108–112. doi: 10.1038/nature11606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Campbell RM, Tummino PJ. Cancer epigenetics drug discovery and development: The challenge of hitting the mark. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:64–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI71605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Knutson SK, Wigle TJ, Warholic NM, et al. A selective inhibitor of EZH2 blocks H3K27 methylation and kills mutant lymphoma cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:890–896. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knutson SK, Kawano S, Minoshima Y, et al. Selective inhibition of EZH2 by EPZ-6438 leads to potent antitumor activity in EZH2 mutant non-hodgkin lymphoma. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;4:842–854. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Knutson SK, Warholic NM, Wigle TJ, et al. Durable tumor regression in genetically altered malignant rhabdoid tumors by inhibition of methyltransferase EZH2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:7922–7927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303800110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sumimoto H, Imabayashi F, Iwata T, Kawakami Y. The BRAF-MAPK signaling pathway is essential for cancer-immune evasion in human melanoma cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1651–1656. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar SM, Yu H, Edwards R, et al. Mutant V600E BRAF increases hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha expression in melanoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3177–3184. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adhikary G, Grun D, Balasubramanian S, Kerr C, Huang JM, Eckert RL. Survival of skin cancer stem cells requires the Ezh2 polycomb group protein. Carcinogenesis. 2015;36:800–810. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgv064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fisher ML, Adhikary G, Xu W, Kerr C, Keillor JW, Eckert RL. Type II transglutaminase stimulates epidermal cancer stem cell epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncotarget. 2015;24:20525–20539. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fisher ML, Keillor JW, Xu W, Eckert RL, Kerr C. Transglutaminase is required for epidermal squamous cell carcinoma stem cell survival. Mol Cancer Res. 2015;7:1083–1094. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-14-0685-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dontu G, Wicha MS. Survival of mammary stem cells in suspension culture: Implications for stem cell biology and neoplasia. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2005;10:75–86. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-2542-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Balasubramanian S, Chew YC, Eckert RL. Sulforaphane suppresses polycomb group protein level via a proteasome-dependent mechanism in skin cancer cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2011;80:870–878. doi: 10.1124/mol.111.072363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Balasubramanian S, Eckert RL. Green tea polyphenol and curcumin inversely regulate human involucrin promoter activity via opposing effects on CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein function. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:24007–24014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314331200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choudhury SR, Balasubramanian S, Chew YC, Han B, Marquez VE, Eckert RL. (−)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate and DZNep reduce polycomb protein level via a proteasome-dependent mechanism in skin cancer cells. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:1525–1532. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adhikary G, Grun D, Kerr C, et al. Identification of a population of epidermal squamous cell carcinoma cells with enhanced potential for tumor formation. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e84324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dontu G, Abdallah WM, Foley JM, et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Balasubramanian S, Lee K, Adhikary G, Gopalakrishnan R, Rorke EA, Eckert RL. The Bmi-1 polycomb group gene in skin cancer: Regulation of function by (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:S65–S68. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Balasubramanian S, Adhikary G, Eckert RL. The Bmi-1 polycomb protein antagonizes the (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-dependent suppression of skin cancer cell survival. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:496–503. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 57.Fischle W, Wang Y, Jacobs SA, Kim Y, Allis CD, Khorasanizadeh S. Molecular basis for the discrimination of repressive methyl-lysine marks in histone H3 by Polycomb and HP1 chromodomains. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1870–1881. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Singh AV, Xiao D, Lew KL, Dhir R, Singh SV. Sulforaphane induces caspase-mediated apoptosis in cultured PC-3 human prostate cancer cells and retards growth of PC-3 xenografts in vivo. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:83–90. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh SV, Srivastava SK, Choi S, et al. Sulforaphane-induced cell death in human prostate cancer cells is initiated by reactive oxygen species. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19911–19924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412443200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dashwood RH, Myzak MC, Ho E. Dietary HDAC inhibitors: Time to rethink weak ligands in cancer chemoprevention? Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:344–349. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Myzak MC, Dashwood WM, Orner GA, Ho E, Dashwood RH. Sulforaphane inhibits histone deacetylase in vivo and suppresses tumorigenesis in Apc-minus mice. FASEB J. 2006;20:506–508. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4785fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li Y, Zhang T. Targeting cancer stem cells with sulforaphane, a dietary component from broccoli and broccoli sprouts. Future Oncol. 2013;9:1097–1103. doi: 10.2217/fon.13.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown GT, Murray GI. Current mechanistic insights into the roles of matrix metalloproteinases in tumor invasion and metastasis. J Pathol. 2015;3:273–281. doi: 10.1002/path.4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jee HG, Lee KE, Kim JB, Shin HK, Youn YK. Sulforaphane inhibits oral carcinoma cell migration and invasion in vitro. Phytother Res. 2011;25:1623–1628. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Brew K, Dinakarpandian D, Nagase H. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: Evolution, structure, and function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1477:267–283. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00279-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shin YJ, Kim JH. The role of EZH2 in the regulation of the activity of matrix metalloproteinases in prostate cancer cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e30393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Deb G, Thakur VS, Limaye AM, Gupta S. Epigenetic induction of tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinase-3 by green tea polyphenols in breast cancer cells. Mol Carcinog. 2015;54:485–499. doi: 10.1002/mc.22121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]