Abstract

AIM: To provide a structural model of the relationship between personality traits, perceived stress, coping strategies, social support, and psychological outcomes in the general population.

METHODS: This is a cross sectional study in which the study group was selected using multistage cluster and convenience sampling among a population of 4 million. For data collection, a total of 4763 individuals were asked to complete a questionnaire on demographics, personality traits, life events, coping with stress, social support, and psychological outcomes such as anxiety and depression. To evaluate the comprehensive relationship between the variables, a path model was fitted.

RESULTS: The standard electronic modules showed that personality traits and perceived stress are important determinants of psychological outcomes. Social support and coping strategies were demonstrated to reduce the increasing cumulative positive effects of neuroticism and perceived stress on the psychological outcomes and enhance the protective effect of extraversion through decreasing the positive effect of perceived stress on the psychological outcomes.

CONCLUSION: Personal resources play an important role in reduction and prevention of anxiety and depression. In order to improve the psychological health, it is necessary to train and reinforce the adaptive coping strategies and social support, and thus, to moderate negative personality traits.

Keywords: Structural equations model, Personality traits, Stressful life events, Social support, Coping strategies, Depression and anxiety

Core tip: Personality traits, stressful life events and personal resources (coping strategies and social support) are among the factors that can influence psychological outcomes. Personality traits have an important role as the basis for coping skills and social support. Stressful life events and personal resources can modulate psychological outcomes. There is a vital role for holistic medicine which addresses the whole aspects of personality, perceived stress, and personal resource for mental health. The presence of a model that includes all the factors influencing the mental health allows planning for improvements with reality-based interventions.

INTRODUCTION

In order to appreciate the depression and the anxiety status as the stress-related negative outcomes, we need to assess the interaction between coping strategies and social support acceptance with perceived stress in the context of personality.

Stress as an inevitable life experience, develops when an individual fails to cope with the external physiological and cognitive distress in daily life[1,2]. Perceived stress is defined as an individual understands the amount of stress he or she is exposed to in a period of time. It incorporates the feeling of uncertainty and instability in life, and depends upon the confidence in one’s ability in dealing with difficulties[3]. Personality is a significant factor in stressful events and is considered the basis for not having the required resources to cope with an unexpected situation[4,5]. It can influence the perception of stress upon the exposure to the stressful event or in reaction to it[6]. As a result, maladaptive personality traits are related to greater distress, while more positive and sociable personalities experience more favorable psychological well-being[7]. Studies have suggested an interaction between personality traits that are independently related to depression and anxiety[8]. Furthermore, different personal and social factors can also influence the reaction to the stressful situations as well as the level of stress[9]. Two types of personal resources that affect adaptation and psychological well-being include coping strategies and social support as the internal and external resources, respectively[10]. The perceived stress has a considerable impact on the coping process which in turn plays an important role in adaptation to stressful life events[11,12]. Coping is an ongoing process that changes in response to variations of the situation[13]. Coping strategies can be categorized into the active and avoidant[14]. Active coping manages the problem cognitively by taking action to mitigate the enfeebling effects of stress[14], while the avoidant coping regulates the negative emotional state activated by the stressors[15]. Coping mechanism can take on various roles in the stressor-symptom relationship, the context that varies by the type of coping[16]. Moreover, personality traits can affect coping in the daily life[17]. Active coping is a protective factor in the stressor-symptom model[16]. On the contrary the avoidance coping is considered a maladaptive response to stressful life events[18]. There is a relationship between psychological distress and different coping strategies[19]. While the problem-focused coping is negatively related to anxiety, stress and depressive symptoms, the avoidant coping is shown to be positively associated with these symptoms[19]. Depression, as the outcome of a defective stress management, may be related to certain coping strategies[20]. Particular types of coping strategies are linked to positive psychological outcomes[21]. For instance, cognitive reinterpretation and social support are associated with lower perceived strain[22]. In general, active coping results in a more effective adjustment to chronically stressful events than the avoidant[23]. Social support is another factor that can moderate the effect of stress[24]. The buffering effect of social support is either by prevention of potential stressful situations to be perceived as the stressor, or by reducing the intensity of the reaction to these events[24]. Social support is related to productive psychological responses, and its absence can be a cause of stress[25,26]. The lack of social support is associated with psychological problems such as depression and anxiety[27]. On the other hand, the presence of resources such as family and friends is associated with a reduction in psychological distress[24]. Little is known about the structural equations through which the stress influences the psychological health. In this study we intended to examine the interaction between personality, perceived stress, coping and social support in stressful situations and to determine their effect on negative psychological outcomes such as anxiety or depression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population and data collection

This cross-sectional study is a part of the “Study of the Epidemiology of Psychological, Alimentary Health and Nutrition” (SEPAHAN)[28]. Multistage cluster and convenience sampling was used to select the group of interest among 4 million people residing in Isfahan province. SEPAHAN study was designed in such a way to enhance the accuracy and response rates by executing the data collection in two separate phases. During the first phase, participants completed a self-administered questionnaire on demographics and lifestyle such as nutritional habits and dietary regimens. In the second phase, different questionnaires provided information on various aspects of psychological variables (response rate: 86.16%). In total, 4763 individuals participated in our study and data were collected on demographics, personality traits, life events, coping with stress, social support, and psychological outcomes such as anxiety and depression. Written informed consent was obtained after clarifying the study protocol and study process. The study was approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Measures

Demographic factors included sex, age, marital status of married or unmarried (single, divorced, widowed) and educational level of graduate and undergraduate.

Big Five Personality Inventory Short Form (NEO FFI): This 60-item scale comprises five personality traits of extraversion, neuroticism, agreeableness, openness, and conscientiousness with 12 items for each. These items are scored from 1 to 5 (strongly disagree to totally agree) with higher scores highlighting a particular personality trait[29]. The reliability of the entire scale (α = 0.70) and subscales (αs > 0.68) has been confirmed[30].

Stressful life events questionnaire: This questionnaire measures the frequency and significance of perceived stress in daily life. It consists of 46 items with 11 domains including home life, financial problems, social relation, personal conflict, job-related stress, educational concerns, job security, loss and separation, sexual life, daily life and health concerns. This scale is rated base on the presence of an stressful life event over the last year from 0 (never) to 5 (very severe)[31,32].

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: The questionnaire consists of 14 items under two scales of depression (α = 0.84) and anxiety (α = 0.82). Each scale has 7 items with a score of 0 to 21. The clinical definition of anxiety or depression is set at a score ≥ 11[33].

Coping Strategies Scale: A multi-component questionnaire to assess the coping with stressful life events. It includes 23 items categorized into five subscales of positive re-interpretation and growth, problem engagement, acceptance, seeking support, and avoidance. Scores are reported separately for each scale with a 3 point Likert type score of 0 (never), 1 (sometimes) or 2 (often)[34]. Its reliability is determined using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (α = 0.84).

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS): The questionnaire consists of 12 items with 5-point Likert-scale which evaluate 3 sources of social support including family, friends, and significant other. Adequate psychometric properties have been found with the MSPSS[35].

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed with SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, United States). A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Continuous variables are shown as mean ± SD and Pearson correlation coefficient was used to test the relationship between personality traits, perceived stress, personal resources (social support and coping strategies), and psychological outcomes (anxiety and depression). To examine the simultaneous comprehensive relationship between studied variables, a path model was fitted. Path analysis as a generalization of the regression model estimates direct, indirect, and total effects of each variable on dependent variable to describe the observed correlation among them[36]. In path analysis some variables are exogenous or endogenous depending on hypothesized pathways. Two separate path models were fitted to evaluate the relationship between personality traits as exogenous variables and perceived stress, and personal resources (social supports and coping strategies) as mediators and psychological outcomes (i.e., anxiety and depression) as endogenous variables. In both fitted models, one of the mediators was considered as a latent variable (coping strategies) and was extracted based on three observed indicators including problem focus coping, emotional focus copping and avoidance. Even though some consider values of 4 and even 5 to indicate a good fit, the χ2 to degree of freedom index (χ2/df) less than 3 is preferred in relation to fitness indices of models in path analysis[37]. Other indices for fitting the model include Normed Fit Index (NFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Goodness Fit Index (GFI), with preferred values over 0.9. In the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) criteria, values up to 0.08 are acceptable, and values equal to or less than 0.05 indicate a good fit.

RESULTS

A total of 4763 respondents with an age of 36.58 ± 8.09 (mean ± SD) years were included in the study; 2106 (44.2%) were male; 2650 (57.2%) were university graduates; and 3776 (81.2%) were married. The study variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mean, standard deviation and range of study variables (n = 4763)

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range | |

| Personality traits | Neuroticism | 18.72 (7.87) | 0-45 |

| Extraversion | 29.03 (7.08) | 0-48 | |

| Openness | 24.04 (5.28) | 0-41 | |

| Agreeableness | 31.00 (6.37) | 0-48 | |

| Conscientiousness | 36.20 (7.22) | 0-48 | |

| Social support | 7.63 (3.64) | 0-12 | |

| Perceived stress | 28.57 (19.86) | 0-132 | |

| Coping strategies | Problem focused coping | 9.65 (2.12) | 0-12 |

| Emotional focused coping | 6.44 (1.49) | 0-8 | |

| Avoidance | 3.41 (1.76) | 0-8 | |

| Psychological outcomes | Anxiety | 3.55 (3.72) | 0-21 |

| Depression | 6.14 (3.37) | 0-21 |

The correlations between personality traits, perceived stress, coping strategies, social support and psychological outcomes are demonstrated in Table 2. Among personality traits, extraversion had the most negative correlation (P < 0.001), whereas neuroticism had the most positive correlation (P < 0.001) with psychological outcomes. The perceived stress had a positive correlation with psychological outcomes as well as with neuroticism among personality traits (P < 0.001). Low levels of social support were related to higher levels of anxiety and depression (P < 0.001). Among personality traits, only neuroticism showed a negative correlation with social support (P < 0.001). Furthermore, neuroticism had a negative correlation with problem-focused and emotional-focused coping (P < 0.001). Meanwhile, a positive correlation was observed between neuroticism and avoidance. Extraversion had the most positive correlation with emotional focused coping, with a non-significant correlation with avoidance.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients between research variables

| Variable | N | E | O | A | C | Anxiety | Depression | |

| Social support | -0.34b | 0.41b | 0.13a | 0.24b | 0.24b | -0.33b | -0.39b | |

| Perceived stress | 0.42b | -0.23a | 0.01 | -0.21a | -0.12a | -0.55b | 0.51b | |

| Coping strategies | Problem focused coping | -0.30b | 0.30b | 0.13a | 0.14a | 0.31b | -0.23b | -0.27b |

| Emotional focused coping | -0.33b | 0.34b | 0.08 | 0.17a | 0.25b | -0.26b | -0.31b | |

| Avoidance | 0.12a | -0.01 | -0.03 | -0.16a | -0.11a | 0.07 | 0.09 | |

| Psychological outcomes | Anxiety | 0.62b | -0.40b | -0.07 | -0.29b | -0.26b | - | 0.76b |

| Depression | 0.63b | -0.50b | -0.14a | -0.30b | -0.29b | 0.76b | - | |

P ≤ 0.05;

P ≤ 0.01. N: Neuroticism; E: Extraversion; O: Openness; A: Agreeableness; C: Conscientiousness.

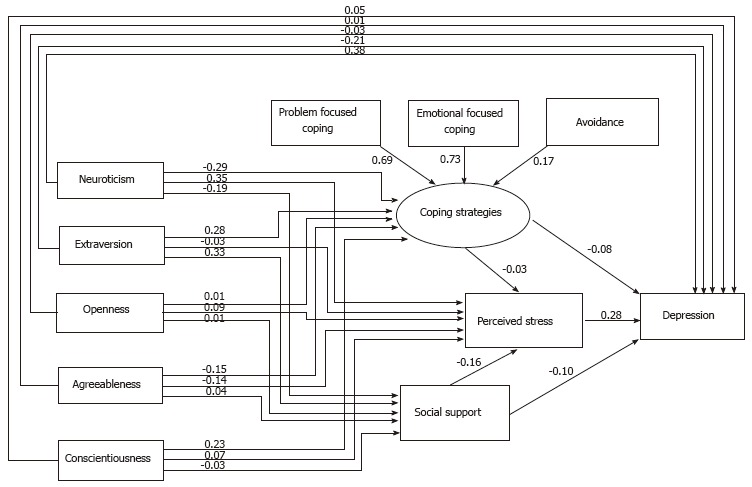

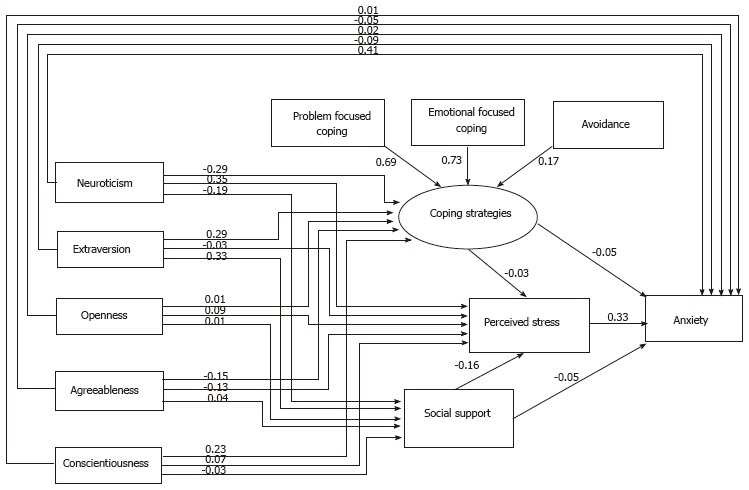

The pathways of personality traits, perceived stress, coping strategies, and social support were analyzed to evaluate their direct, indirect, and total effects on psychological outcomes of anxiety or depression (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Table 3). As is seen from path coefficients, neuroticism had the most direct (0.38), indirect (0.15) and total positive effects (0.52) and extraversion showed the most direct (-0.21), indirect (0.14) and total negative effects (-0.28) on depression. Similar results on the direct, indirect and total effects of neuroticism regarding anxiety were observed, however, extraversion (-0.19) and agreeableness (-0.04) had direct negative effects on anxiety. Moreover, the perceived stress had direct positive effects on depression (0.28) and anxiety (0.33). Personal resources including social support (-0.09) and coping strategies (-0.08) had direct negative effects on depression. Social support and coping also showed a direct negative effect on anxiety (-0.05). The mediating effects of perceived stress, social support and coping strategies were also examined. Personality traits were shown to be influential on perceived stress and personal resources. Out of analyzed personality traits, neuroticism (0.35) and openness (0.09) had positive effects on perceived stress, agreeableness, on the other hand, had a negative effect (-0.14). Among personal resources, agreeableness (-0.15) and neuroticism (-0.29) had negative effects on coping strategies. Other traits of extraversion (0.28) and conscientiousness (0.23) had positive effects. Neuroticism was the sole factor with a negative effect on social support (-0.19). Extraversion was found to have a positive effect on social support (0.33). Analyses of the total effects showed a significant indirect effect of neuroticism, extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and openness on depression and anxiety. Perceived stress positively mediated the positive effects of neuroticism and negative effects of extraversion on psychological outcomes. Whereas copping strategies and social support, in part, negatively mediated positive effects of neuroticism and negative effects of extraversion. The perceived stress positively mediated the negative effects of other personality traits on psychological outcomes, while coping strategies and social support enhanced the negative effects. On one hand, social support and coping strategies reduced the increasing cumulative positive effects of neuroticism and perceived stress on psychological outcomes, on the other hand, they strengthened the protective effect of extraversion through decreasing the positive effect of perceived stress on psychological outcomes. Table 4 shows the model fit indices for the final models. The model chi square divided by degree of freedom was less than 3 for both fitted models. The fit indices of GFI, NFI, TLI, and CFI in the models were all above 0.9, and RMSEAs were in an acceptable range.

Figure 1.

Path coefficients showing direct and indirect effects of personality traits, stressful events, social support and coping strategies on depression.

Figure 2.

Path coefficients showing direct and indirect effects of personality traits, stressful events, social support and coping strategies on anxiety.

Table 3.

Regression coefficients for structural equations model

|

Depression |

Anxiety |

|||||

| Direct | Indirect | Total | Direct | Indirect | Total | |

| Neuroticism | 0.378a | 0.145a | 0.523a | 0.406a | 0.155a | 0.561a |

| Extraversion | -0.208a | -0.145a | -0.283a | -0.085a | -0.090a | -0.175a |

| Openness | -0.037a | 0.026 | -0.011 | 0.015 | 0.025a | 0.040a |

| Agreeableness | 0.014 | -0.033 | -0.019 | -0.043a | -0.037a | -0.080a |

| Conscientiousness | 0.045a | 0.006 | 0.051a | 0.010 | 0.006 | 0.016 |

| Social support | -0.098a | -0.044 | -0.142a | -0.047a | -0.021 | -0.068a |

| Perceived stress | 0.279a | 0.000 | 0.279a | 0.330a | 0.010 | 0.340a |

| Coping strategies | -0.080a | 0.006 | -0.074a | -0.053a | 0.005 | -0.048a |

P ≤ 0.05.

Table 4.

Model fit indices for the final modified models

|

Goodness of fit indices 8k |

|||||

| χ2/d.f | NFI | CFI | GFI | RMSEA (Lower-upper) | |

| Depression | 1.9 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 | 0.091 (0.085-0.097) |

| Anxiety | 2.1 | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.089 (0.084-0.095) |

NFI: Normed fit index; CFI: Comparative fit index; GFI: Goodness of fit index; RMSEA: Root mean square error of approximation.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the relationship between personality traits, perceived stress, coping strategies, and social support with psychological outcomes such as depression and anxiety. Our results showed that among personality traits, neuroticism and extraversion exert the strongest direct and indirect effects on psychological outcomes. In other words, neuroticism had the most positive effect by increasing the depression and anxiety, and extraversion had the most negative effect by decreasing these psychological outcomes. The results are consistent with findings of similar studies[38,39]. It is discussed that neuroticism is characterized by disordered emotional regulation, motivation, and interpersonal skills leading to a negative mood experience[40]. Consequently, those with neuroticism may present with psychological desperateness and failing process of thought[41]. On the contrary, extraversion is usually positively associated with more interpersonal interactions, capacity for having a joyful and active appreciation of stressful situations[42]. Therefore individuals scoring high on this trait are more sociable, person-oriented, fun-loving and affectionate. In addition, we showed that perceived stress had strong negative effects on psychological outcomes. It is estimated that approximately 70% of initial depressive episodes are preceded by a stressful life event which plays a causal role in about 20%-50% of cases[43,44]. The relationship between various forms of stressful events such as work stressors and housing problems and various psychological outcomes has been shown in several studies[16,24]. It could be concluded that the inability to properly manage the emotional responses upon exposure to stressful situations can lead to longer and more severe periods of emotional difficulties.

With regards to personal resources, our results showed that social support and coping strategies generally decrease psychological outcomes. Problem-focused coping strategies and some types of emotional-focused coping strategies are associated with better health outcomes[45,46]. Problem-focused coping helps to manage the stress causing problem[47], and emotional-focused coping diminishes the negative emotions associated with stressor. However, avoidance coping as a type of passive coping is highly related to psychological outcomes due to minimizing, denying or ignoring to deal with a stressful situation[16,48].

Meanwhile, social support resources such as family and friends are associated with diminishing psychological distress[24]. Social support prevents a situation to be perceived as distress and also promotes healthy behavior at the time of stress[49]. It can also exert its influence by positive thinking and cognitive restructuring[50]. In general, it can be concluded that factors such as personality traits, stressful life events and personal resources have various effects on psychological outcomes. Personal resources can negatively moderate the effects of neuroticism and stressors on psychological outcomes. Contrary to our expectations, the role of personal resources in reducing psychological outcomes was demonstrated to be weak. This finding might be due to the high level of daily stressful events in our community in which personal resources seem to be insufficient or ineffective. Previous studies have shown that coping strategies appear to be functioning differently based on the nature of stressor, the social context of stressful event, and individual’s personality[51]. In a highly frequent stressful context, the individual’s ability to respond to future stressors can also be impaired[24]. Having said that, the relation between the type and severity of stressor with particular coping strategies appear to be the most important predictor of psychological outcomes.

Severe emotional reactions to stressors can exacerbate maladaptive and neuroticistic behaviors. Moreover, individuals with neuroticism negatively evaluate and interpret events and ambiguous stimuli as threatening and tend to remember these unpleasant events more than emotionally stable individuals[52]. Therefore, these individuals mostly get involved in maladaptive coping strategies like avoidance[53]. Personality characteristics influence the degree to which an individual seeks social support when confronted by an stressful event[54]. Neuroticism interferes with seeking of social support and has a negative effect on outcomes. Extraversion, on the contrary, acts as a protective factor in the stress and coping process[11]. Even though there is a growing trend in our community for learning of coping process and gathering information on social support system, lack of proper and sufficient training early in childhood makes individuals incapable of using these resources as a continual skill. All in all, although this study demonstrates personality traits and perceived stress as the most important determinants of psychological outcomes, the presence and accessibility of personal resources in reducing and prevention of anxiety and depression need to be highlighted. An improved social support system is a necessity to better psychological health and well-being. It is imperative to start training for personal resources and to reinforce appropriate behavioral reactions early in childhood through the educational system and family training sessions.

Large sample size and validated instruments are among the strengths of this study. The main limitations are self-report questionnaires and no control over biasing factors affecting the level of stress. In addition, due to the complexity of the model, the relationship of each coping strategy with other research variables was not evaluated.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to extend their grateful thanks to participants of this study and authorities of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences for their remarkable cooperation.

COMMENTS

Background

Personality traits and stressful life events lead to psychological distress. Coping strategies and social support can predict the occurrence of depression and anxiety, considering their role as internal and external stress-controlling resources, respectively. It is important to determine the interaction between coping strategies and social support with the stress in the context of personality.

Research frontiers

This is a path analysis to determine the interaction between coping strategies and acceptance of social support with perceived stress in the context of personality in the normal population.

Innovations and breakthroughs

This work deals with the interaction between these four factors in such a large scale that can be considered a basis for designing social studies involving these variables.

Applications

This model demonstrates the efficacy of multi-pronged interventions in promoting the psychological well-being.

Terminology

Perceived stress: The understanding of an individual of the amount of stress he or she is exposed to in a given point of time or specific period. Personality traits: Five major traits underling personality. Social support: The perception of being cared for, availability of assistance and being a part of supportive social network. Coping strategies: The internal effort that seeks to minimize the distress to solve personal and interpersonal conflicts.

Peer-review

The authors examine a hot and interesting topic.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board and ethics committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Informed consent statement: All study participants provided informed written consent prior to study enrollment.

Conflict-of-interest statement: There are no conflicts of interest to report.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: January 15, 2016

First decision: February 2, 2016

Article in press: April 22, 2016

P- Reviewer: Chakrabarti S, Heiser P S- Editor: Qiu S L- Editor: A E- Editor: Wu HL

References

- 1.Tan JT, Winkelman C. The contribution of stress level, coping styles and personality traits to international students’ academic performance. Aust, Cathol: Univ, Locked Bag; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suldo SM, Shaunessy E, Hardesty R. Relationships among stress, coping, and mental health in high-achieving high school students. Psychol Sch. 2008;45:273–290. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Phillips AC. Perceived stressor Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. 2016-02-12: 1453-1454. Available from: http//link.springer.com/reference work entry.

- 4.Dumitru V, Cozman D. The relationship between stress and personality factors. Hum Vet Med. 2012;4:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ongori H, Agolla J. An assessment of academic stress among undergraduate students: The case of University of Botswana. Educ Res Rev. 2009;4:63–70. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1995;69:890–902. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vollrath M, Torgersen S. Personality types and coping. Pers Individ Dif. 2000;29:367–378. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsudaira T, Kitamura T. Personality traits as risk factors of depression and anxiety among Japanese students. J Clin Psychol. 2006;62:97–109. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rashidi B, Hosseini S. Infertility stress: The role of coping strategies, personality trait, and social support. J Fam Reprod Heal. 2011;5:101–108. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsu HC, Tung HJ. What makes you good and happy? Effects of internal and external resources to adaptation and psychological well-being for the disabled elderly in Taiwan. Aging Ment Health. 2010;14:851–860. doi: 10.1080/13607861003800997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kardum I, Krapić N. Personality traits, stressful life events, and coping styles in early adolescence. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30:503–515. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crockett LJ, Iturbide MI, Torres Stone RA, McGinley M, Raffaelli M, Carlo G. Acculturative stress, social support, and coping: relations to psychological adjustment among Mexican American college students. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2007;13:347–355. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moos RH, Holahan CJ. Dispositional and contextual perspectives on coping: toward an integrative framework. J Clin Psychol. 2003;59:1387–1403. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Compas BE, Connor-Smith JK, Saltzman H, Thomsen AH, Wadsworth ME. Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:87–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santacana MFI, Kirchner T, Abad J, Amador JA. Differences between genders in coping: Different coping strategies or different stressors? Anu Psicol UB J Psychol. 2012;42:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snow DL, Swan SC, Raghavan C, Connell CM, Klein I. The relationship of work stressors, coping and social support to psychological symptoms among female secretarial employees. Work Stress. 2003;17:241–263. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pierce G, Sarason I, Sarason B. Handbook of coping: Theory, research, applications. New York: Wiley; 1996. Coping and social support; pp. 434–451. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holahan CJ, Moos RH. Risk, resistance, and psychological distress: a longitudinal analysis with adults and children. J Abnorm Psychol. 1987;96:3–13. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.96.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Berkel H. The relationship between Personality, coping styles and stress, anxiety and depression ([updated 2014 Dec 10]) Available from: http//ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/2612.

- 20.Christensen MV, Kessing LV. Clinical use of coping in affective disorder, a critical review of the literature. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2005;1:20. doi: 10.1186/1745-0179-1-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zołnierczyk-Zreda D. The effects of worksite stress management intervention on changes in coping styles. Int J Occup Saf Ergon. 2002;8:465–482. doi: 10.1080/10803548.2002.11076548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Decker PJ, Borgen FH. Dimensions of work appraisal: Stress, strain, coping, job satisfaction, and negative affectivity. J Couns Psychol. 1993;40:470–478. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin HS, Probst JC, Hsu YC. Depression among female psychiatric nurses in southern Taiwan: main and moderating effects of job stress, coping behaviour and social support. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2342–2354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03216.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith CA, Smith CJ, Kearns RA, Abbott MW. Housing stressors, social support and psychological distress. Soc Sci Med. 1993;37:603–612. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90099-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rees T, Mitchell I, Evans L, Hardy L. Stressors, social support and psychological responses to sport injury in high- and low-performance standard participants. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2010;11:505–512. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo Y, Wang H. Correlation research on psychological health impact on nursing students against stress, coping way and social support. Nurse Educ Today. 2009;29:5–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teoh H, Rose P. Child mental health: Integrating Malaysian needs with international experiences. In: Haque A, editor. Mental health in Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press; 2001. pp. 103–121. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adibi P, Keshteli A, Esmaillzadeh A. The study on the epidemiology of psychological, alimentary health and nutrition (SEPAHAN): overview of methodology. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17:S291–297. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Costa P, McCrae R. NEO PI-R professional manual. Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. pp. 653–655. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Barlett CP, Anderson CA. Direct and indirect relations between the Big 5 personality traits and aggressive and violent behavior. Pers Individ Dif. 2012;52:870–875. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roohafza H, Ramezani M, Sadeghi M, Shahnam M, Zolfagari B, Sarafzadegan N. Development and validation of the stressful life event questionnaire. Int J Public Health. 2011;56:441–448. doi: 10.1007/s00038-011-0232-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sali R, Roohafza H, Sadeghi M, Andalib E, Shavandi H, Sarrafzadegan N. Validation of the revised stressful life event questionnaire using a hybrid model of genetic algorithm and artificial neural networks. Comput Math Methods Med. 2013;2013:601640. doi: 10.1155/2013/601640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Snaith RP, Zigmond AS. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986;292:344. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6516.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:267–283. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M. Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Articles. 2008;6:53–60. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model A Multidiscip J. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson SL, Turner RJ, Iwata N. BIS/BAS Levels and Psychiatric Disorder: An Epidemiological Study. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2003;25:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Graaf R, Bijl RV, ten Have M, Beekman AT, Vollebergh WA. Rapid onset of comorbidity of common mental disorders: findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS) Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;109:55–63. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-690x.2003.00222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matthews G, Deary I, Whiteman M. Personality traits. Oxford city: Cambridge University Press; 2003. pp. 1–493. [Google Scholar]

- 41.karimzade A. Besharat mohammad ali. An investigation of the Relationship Between Personality Dimensions and Stress Coping Styles. Procedia - Soc Behav Sci. 2011;30:797–802. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallagher DJ. Extraversion, neuroticism and appraisal of stressful academic events. Pers Individ Dif. 1990;11:1053–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hammen C. Stress and Depression. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2005;1:293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Monroe SM, Harkness KL. Life stress, the “kindling” hypothesis, and the recurrence of depression: considerations from a life stress perspective. Psychol Rev. 2005;112:417–445. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.2.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Greenglass E, Burke R. The relationship between stress and coping among Type As. J Soc Behav Personal. 1991;6:361–373. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Violanti JM. Coping strategies among police recruits in a high-stress training environment. J Soc Psychol. 1992;132:717–729. doi: 10.1080/00224545.1992.9712102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress. Apprais coping. 1984;1:725. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Brennan PL, Schutte KK. Stress generation, avoidance coping, and depressive symptoms: a 10-year model. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2005;73:658–666. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Makar AB, McMartin KE, Palese M, Tephly TR. Formate assay in body fluids: application in methanol poisoning. Biochem Med. 1975;13:117–126. doi: 10.1016/0006-2944(75)90147-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeLongis A, Holtzman S. Coping in context: the role of stress, social support, and personality in coping. J Pers. 2005;73:1633–1656. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Penley JA, Tomaka J. Associations among the Big Five, emotional responses, and coping with acute stress. Pers Individ Dif. 2002;32:1215–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Watson D, Hubbard B. Adaptational Style and Dispositional Structure: Coping in the Context of the Five-Factor Model. J Pers. 1996;64:737–774. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Houston BK, Vavak CR. Cynical hostility: developmental factors, psychosocial correlates, and health behaviors. Health Psychol. 1991;10:9–17. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]