Abstract

The LIM-homeobox transcription factors LHX2 and LHX3s (LHX3a and LHX3b) are thought to be involved in regulating the pituitary glycoprotein hormone subunit genes Cga and Fshβ. These two factors show considerable differences in their amino acid sequences for DNA binding and protein-protein interactions and in their vital function in pituitary development. Hence, we compared the DNA binding properties and transcriptional activities of Cga and Fshβ between LHX2 and LHX3s. A gel mobility shift assay for approximately 1.1 kb upstream of Cga and 2.0 kb upstream of Fshβ varied in binding profiles between LHX2 and LHX3s. DNase I footprinting revealed DNA binding sites in 8 regions of the Cga promoter for LHX2 and LHX3s with small differences in the binding range and strength. In the Fshβ promoter, 14 binding sites were identified for LHX2 and LHX3, respectively. There were alternative binding sites to either gene in addition to similar differences observed in the Cga promoter. The transcriptional activities of LHX2 and LHX3s according to a reporter assay showed cell-type dependent activity with repression in the pituitary gonadotrope lineage LβT2 cells and stimulation in Chinese hamster ovary lineage CHO cells. Reactivity of LHX2 and LHX3s was observed in all regions, and differences were observed in the 5'-upstream region of Fshβ. However, immunohistochemistry showed that LHX2 resides in a small number of gonadotropes in contrast to LHX3. Thus, LHX3 mainly controls Cga and Fshβ expression.

Keywords: Gene regulation, Glycoprotein hormone, LHX2, LHX3, LIM-homeodomain, Pituitary

The pituitary gonadotropin hormones follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) are dimeric proteins composed of a common glycoprotein hormone α subunit (Cgα) and a unique β subunit (FSHβ and LHβ) that confers biological specificity for their respective hormone functions. The regulatory mechanisms of the three subunit genes constituting two types of gonadotropins are of special interest because three subunit genes are modulated in the same cell with distinct roles in gametogenesis in both sexes. To resolve gene regulation on the molecular level, several approaches have been used [1] and have identified many regulatory factors and elements governing the basal and cell-specific expression of the subunit gene [2]. We have more recently reported a novel regulation with long-fatty acid for Fshβ [3].

Among the various types of transcription factors known to participate in the control of gonadotropin genes, LIM homeobox 3 (LHX3, also known as P-Lim/LIM-3) plays a crucial role in pituitary development [4, 5]. Lhx3-knockout mice showed that this gene is essential for early pituitary structural development and later for the differentiation of cell types in the anterior and intermediate lobes. LHX3 also participates in the activation of hormone gene expression, either alone or in synergy with other regulatory factors [6,7,8,9]. Subsequently, LHX3 was identified as a regulator of porcine Fshβ [10]. In contrast, LHX2 (also known as LH2), which belongs to the same subfamily of LHX3, plays an important role in eye, forebrain, and definitive erythrocyte development [11]. Lhx2-knockout mice showed a defect in the posterior lobes that induced the disorganization of the anterior/intermediate lobes with differentiation of their hormone-producing cells [12]. LHX2 was first identified as a regulatory factor for Cga in the pituitary tumor-derived cell line αT3-1 [13]. More recently, we cloned Lhx2 cDNA from the porcine anterior pituitary cDNA library using the Yeast One-Hybrid Cloning System and the upstream region of Fshβ as a bait sequence. The results demonstrated that LHX2 modulates porcine Fshβ by binding to plural sites of the promoter [14].

LIM homeobox transcription factors are characterized as having two LIM domains and a homeobox domain. LIM domains are known to have highly divergent sequences, providing many different binding properties and forming various combinations [15]. The homeobox domain is composed of 60 amino acids that form three α-helixes characterized by their DNA binding properties as well as dimerization [16,17,18,19]. However, differences in the residues important for DNA binding or dimerization alter binding specificity or the loss of dimerization [20,21,22]. LHX2 and LHX3 show a similarity of less than about 50%, indicating that their DNA binding and/or transcriptional regulation activities also differ.

Considering the dissimilarity in the domain sequences, the present study aimed to compare the DNA binding properties and transcriptional activities of LHX2 and LHX3. In addition, because different isoforms of human LHX3 have been reported [9] but those in porcine species remain unknown, we cloned their full-length cDNAs. As expected, LHX2 and LHX3 showed some differences in their DNA binding abilities in their strengths and specificities as well as in their regulatory potencies for several promoter regions of both genes. Immunohistochemical analysis, however, demonstrated a rare population of LHX2 in contrast to LHX3 in FSHβ-positive cells. The present study showed that LHX2 and LHX3 differentially regulate Fshβ and Cga.

Materials and Methods

Cloning of porcine LIM-homeodomain transcription factor Lhx3

The amino terminus of the porcine Lhx3a and Lhx3b was first determined using a primer set by PCR for the porcine pituitary cDNA library [23]. Next, the forward primers for the amino terminus of Lhx3a (5′-GGGGAATTCGCCATGCTGCTGGAAACGGAGCTGGCGGG-3′) and Lhx3b (5′-GGGGAATTCGCCATGGAAGCGCGCGGGGAGCTG-3′) were synthesized and used to amplify their full-length cDNAs together with a common reverse primer (5′-TCCTCGAGCTGGGGCCTCAGTCAGAACTG-3′), followed by confirmation of the nucleotide sequence of the amplified DNAs.

Construction of vectors for production of recombinant protein, expression in mammalian cells, and promoter assay

The full-length expression vector of porcine Lhx2, Lhx3a, Lhx3b, and Lhx3-del (consisting of a 28–406 amino acid region with a primer 5′-GAGAATTCGCGATGGATCCCACTGTGTGCC-3′ based on a previous paper [24]) was constructed in the mammalian expression vector, pcDNA3.1/Zeo+ (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). For the DNA-binding assay, recombinant proteins were produced by cloning of the truncate cDNAs, ΔLIM-Lhx2 (ΔLIM-LHX2 consisting of amino acid numbers 170–406) and ΔLIM-Lhx3 (ΔLIM-LHX3 consisting of 148–401), into the pET32a vector, followed by expression in Escherichia coli BL21-CodonPlus (DE3)-RIPL (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA), since the LIM domains aggregate by interacting as described previously [25]. The recombinant proteins were expressed and prepared using an Overnight Express Autoinduction System 1 (Novagen, Madison, WI, USA), followed by purification using His-Tag Mag beads (Toyobo, Osaka, Japan).

The following vectors were constructed for the promoter assay in pSEAP-Basic (Clontech Laboratories, Mountain View, CA, USA; αGSU (−1059/+12), αGSU (−798/+12), αGSU (−551/+12), αGSU (−239/+12), and αGSU (−100/+12) for Cga [13] and FSHβ (–1965/+10), FSHβ (–985/+10), FSHβ (–238/+10), and FSHβ (–103/+10) for Fshβ [14], respectively.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and DNase I footprinting assay

The production of FAM-labeled DNA fragments was conducted as described previously [26]. EMSA and DNase I footprinting were also carried out as previously described [23, 27].

Cell culture, transfection, and promoter assay

A transient transfection assay was carried out using LβT2 cells and Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO) as previously described [28]. LβT2 cells, which were kindly provided by Dr PL Mellon (University of California, San Diego, CA, USA), are a mouse pituitary gonadotrope lineage cell line [29] that endogenously expresses the gonadotropin genes Cga, Lhβ, and Fshβ [30]. CHO cells are a non-endocrine cell line. After incubation for more than 48 h, an aliquot (5 μl) of cultured medium was assayed for secreted alkaline phosphatase activity using the Phospha-Light Reporter Gene Assay System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with a MiniLumat LB 9506 luminometer (Berthold, Wildbad, Germany). All values were expressed as the mean ± SD of quadruplicate transfections in two independent experiments. The reproducibility and reliability of the reporter assay without an internal control were conducted as described in our previous paper [31]. Statistical significance was calculated by Dunetts’ test with the F-test.

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Total RNAs, which were extracted from the porcine anterior pituitaries of German Landrace pigs with intact gonads of both sexes during the fetal (f40, f50, f65, f82, f95, and f110) and postnatal periods (p8, p60, p160 (prepuberty), and p230 (sexually matured)), were kindly supplied by Dr F Elsaesser and pooled for 1–6 individuals of the respective age and sex for cDNA synthesis as previously described [32].

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using a specific primer set (Supplementary Table 1: online only) in duplicate with the same threshold line for Lhx3a, Lhx3b, and cyclophilin A (used as an internal control), and data were evaluated using the comparative CT method (ΔΔCT method) as previously described [14]. The DNA sequences of the PCR products were confirmed.

Immunohistochemistry

The pituitaries on postnatal day (P) 15 from S100β-GFP rats [33] were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, overnight at 4°C, followed by immersion in 30% trehalose in 20 mM HEPES for tissue cryoprotection. Samples were embedded in Tissue-Tek O.C.T compound (Sakura Finetek Japan, Tokyo, Japan) and frozen immediately. Frozen sections (6-μm-thick) from the coronal plane were prepared. After washing with 20 mM HEPES-100 mM NaCl, pH 7.5 (HEPES buffer), these sections were reacted with primary antibodies at appropriate dilutions with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum and 0.4% (v/v) Triton X-100 in HEPES buffer overnight at room temperature. Primary antibodies used were rabbit IgG against mouse LHX2 (1:200 dilution, kindly provided by Dr Es Monuki at University of California [34], rabbit IgG against mouse LHX3 (recognizes both LHX3a and LHX3b; 1:250 dilution, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), and chicken IgY against jellyfish GFP (Aves Labs, Tigard, OR, USA). Guinea pig antisera against the pituitary hormones rat FSHβ (1:40,000 dilution), rat PRL (1:10,000 dilution), and rat TSHβ (1:100,000 dilution) were kindly provided by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney courtesy of Dr AF Parlow. Guinea pig antiserum against rat ACTH (1:10,000 dilution) and rat GH (1:6,000 dilution) were produced and kindly provided by Dr S Tanaka of Shizuoka University (Shizuoka, Japan). After the immunoreaction, the sections were washed with HEPES buffer and then incubated with secondary antibodies using Cy3- or Cy5-conjugated AffiniPure donkey anti-rabbit, guinea pig IgG and chicken IgY (1:500 dilution; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA). The sections were washed with HEPES buffer and then enclosed in VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium with 4′, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Immunofluorescence was observed by fluorescence microscopy using a BZ-8000 microscope (KEYENCE, Osaka, Japan).

Results

Cloning of porcine Lhx3 isoforms

We determined the complete sequence of porcine LHX3 isoforms, as only partial sequences of the N-terminus of the two isoforms have been reported [24]. First, a common reverse primer was employed to determine the nucleotide sequences of the two isoforms, followed by amplification of the full-length isoforms (Lhx3a and Lhx3b) using specific forward primers containing the start codon ATG for translation. The nucleotide sequences revealed that the amino acid sequences were 401 and 403 residues for LHX3a and LHX3b, respectively (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2: online only; sequences were deposited to DDBJ as Accession No. AB797327 and AB797328). The amino acid Arg at position 26 of LHX3a differed from the previously identified residue Pro [24], while other N-terminal sequences of LHX3a and LHX3b were identical.

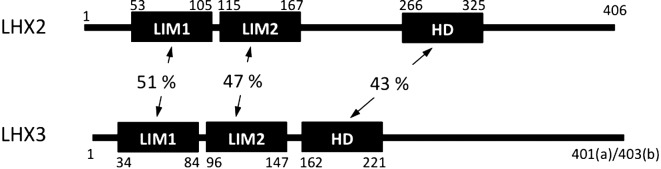

The similarity of the amino acid sequences between LHX2 and LHX3 was examined, as shown in Fig. 1. Two LIM domains, which are known to be important in protein-protein interactions, showed only 51 and 47% identities. Additionally, the homeobox domain, which is important for DNA-binding, showed a very low similarity of 43%, indicating that the two cognate proteins have different roles in gene regulation.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of structures of porcine LHX2 and LHX3. LIM-homeodomain transcription factors are composed of two LIM domains (LIM1 and LIM2) and a DNA-binding homeodomain (HD), with numbered amino acid positions (LHX2 and LHX3a). LHX3a and LHX3b are composed of 401 (a) and 403 (b) amino acids, respectively. The homology (%) of the domains is indicated between the diagrams.

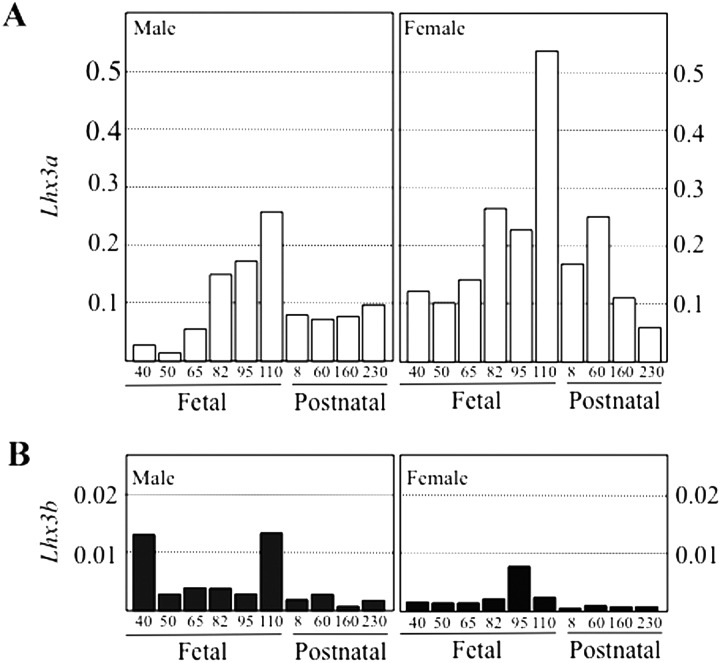

EMSA and DNase I footprinting

EMSA was carried out for the FAM-labeled upstream fragments of Cga and Fshβ. The results showed remarkable multiple-shift bands, except for weak bands for the –798/–501 bp fragment of Cga (Fig. 2A) and for the –706/–541 bp fragment of Fshβ (Fig. 2B). All shift band patterns differed between ΔLIM-LHX2 and ΔLIM-LHX3.

Fig. 2.

Electrophoretic gel mobility shift assay of LHX2 and LHX3. Upstream fragments of Cga (A) and Fshβ (B) are indicated with a line, (thick bar in B indicates Fd2) and nucleotide number above the electrogram. The mixture without protein (-) or with recombinant LIM domain-deleted LHX2 (ΔLIM-LHX2; a) and LHX3 (ΔLIM-LHX3; b) proteins and FAM-labeled fragments were analyzed on a 4% polyacrylamide gel followed by visualization with a fluorescence viewer.

DNase I footprinting analyses were performed to determine the binding sequence, and the profiles with or without ΔLIM-LHX2 or ΔLIM-LHX3 were compared. Protection from DNase I digestion was observed in several regions of the Cga (Supplementary Fig. 3A: online only) and Fshβ (Supplementary Fig. 3B) promoters. We identified 8 binding sites in both ΔLIM-LHX2 and ΔLIM-LHX3 upstream of Cga (Table 1). The binding sites of ΔLIM-LHX2 were found at 14 positions, which agree with the results of our previous study [14], while ΔLIM-LHX3 showed 14 binding sites upstream of Fshβ (Table 2). DNase I footprinting analyses profiles were similar but showed differences in the binding strength and range in each region, which were comparable to the differences observed on the EMSA profiles (Fig. 2). The 6 binding sequences on Cga and 13 on Fshβ contained the nucleotide sequence TAAT/ATTA (Tables 1 and 2), which is known as a core binding motif for homeodomain transcription factors [16,17,18,19].

Table 1. Binding sites for LHX3 and LHX2 in the porcine Cga promoter.

| LHX3 | LHX2 | |

| −1053/−1029 | 5'-GAAGaTGaTACTAATTCaTAT-3' | −1053/−1029 |

| −941/−931 | 5'-AGAAATCAACT-3' | −941/−931 |

| −922/−916 | 5'-ATAATAA-3' | −922/−910 |

| −893/−890 | 5'-TTTG-3‘ | −893/−890 |

| −493/−483 | 5'-TCCTTATTAAA-3' | −494/−483 |

| −471/−439 | 5'-AAATATAATTtaCA-3' | −471/−439 |

| −340/−326 | 5'-TATAATCA-3' | −340/−329 |

| −132/−124 | 5'-ATGGTAATT-3' | −137/−119 |

Table 2. Binding sites for LHX3 and LHX2 in the porcine Fshβ promoter.

| LHX3 | LHX2 | |

| −1914/−1899 | 5'-TCCaTTCaTTtGTGT-3‘ | −1915/−1899 |

| −1882/−1865 | 5'-ATATAATTGTAATCATAT-3' | −1880/−1868 |

| −1799/−1787 | 5'-TTGACAATTACT-3' | −1799/−1768 |

| −1441/−1429 | 5'-CATGCCAATTATA-3' | −1441/−1422 |

| −1166/−1145 | 5'-AATCAGATTCTTTGATTATTT-3' | −1156/−1145 |

| −836/−826 | 5'-TAATTAATT-3' | −836/−827 |

| −820/−810 | 5'-TTAATTAATTG-3' | −818/−810 |

| −808/−798 | 5'-TCAATTAaTA-3' | −808/−798 |

| −467/−454 | 5'-AAATATAATTtaCA-3' | −466/−454 |

| −440/−433 | 5'-TATAATCA-3' | −440/−433 |

| −380/−369 | 5'-GTAACTTATTAACC-3' | −380/−367 |

| −301/−287 | 5'-TCCCCAAATTAAAT-3' | −298/−287 |

| −262/−254 | 5'-GACTTAATT-3' | −260/−254 |

| −219/−206 | 5'-AAATTTAATTTgTA-3' | −218/−206 |

This study examined approximately –2 kb upstream of promoter. LHX2 binding sites are based on the results of Kato et al. [14].

Transcriptional activity of porcine Cga promoter by LHX2 and LHX3

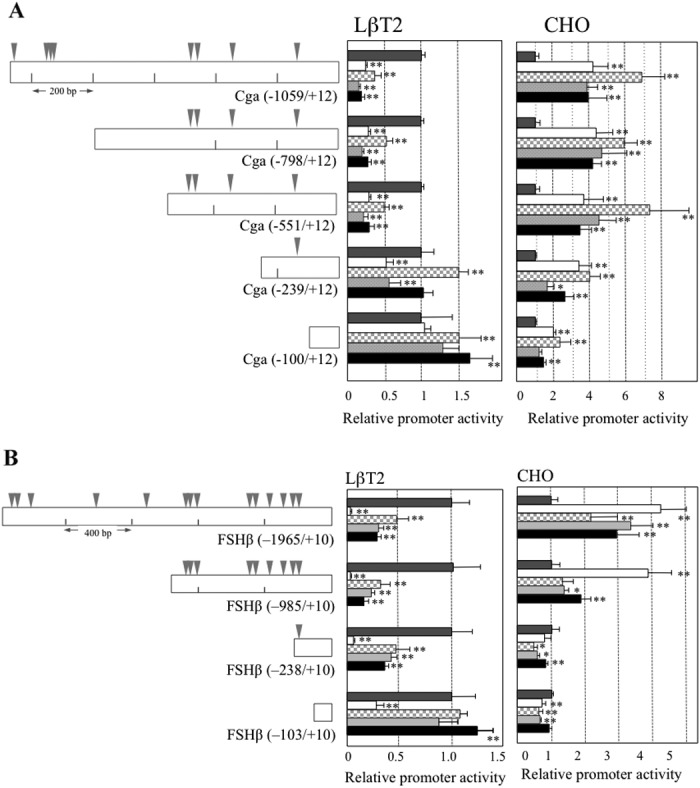

In LβT2 cells, LHX2 and LHX3b repressed Cga promoter activity over the −101 bp region, while LHX3a and LHX-del repressed activity over the −240 bp region (Fig. 3A). Repression observed in the −239/−101 bp region was stronger by LHX2 compared with LHX3s. In contrast, in CHO cells, although LHX2 and LHX3a were slightly activated in the −100/+12 bp region, further activation with LHX2 and LHX3a was observed over the −240 bp region. These results indicate that activation occurred between −551/−101 bp.

Fig. 3.

Transient transfection assay of porcine Cga and Fshβ promoters in LβT2 and CHO cells. Diagram of the truncated fragments of Cga (A) and Fshβ (B) promoters fused with the SEAP gene in the pSEAP2-Basic vector are indicated in the left panel. Inverted triangles represent the binding site common (gray) to LHX2 and LHX3. Transfection was performed in LβT2 (middle panel) and CHO (right panel) cells with pcDNA3.1 harboring without (dark-gray bar), with Lhx2 (open bar), and Lhx3a (checked bar), Lhx3b (light-gray bar), or Lhx3-del (solid bar). An aliquot of cultured medium was used for the SEAP assay. Reporter gene activities are indicated relative to that of the pcDNA3.1 vector. Data (mean ± SD) are the means of quadruplicate transfections from two independent experiments. Asterisks indicate statistical significance by Dunnett’s test with F-test. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

Transcriptional activity of porcine Fshβ promoter by LHX2 and LHX3

LHX2 and LHX3b showed repressive activity for the Fshβ promoter in LβT2 cells (Fig. 3B), as shown for the Cga promoter. LHX2 showed notable repression of FSHβ (−103/+10), which showed putative binding site for LHX2, and more intense repression from −104 to −1965 bp. LHX3s showed rather weak repression from −104 to −1965 bp. In contrast to the activity in LβT2 cells, LHX2 and LHX3s activated the Fshβ promoter. In CHO cells, LHX2 activated for over −239 bp, while LHX3s showed similar activation at −986 bp (Fig. 3B). The results indicate that activation occurred at the −985/−239 bp region for LHX2 and the −1965/−986 bp region for LHX3a.

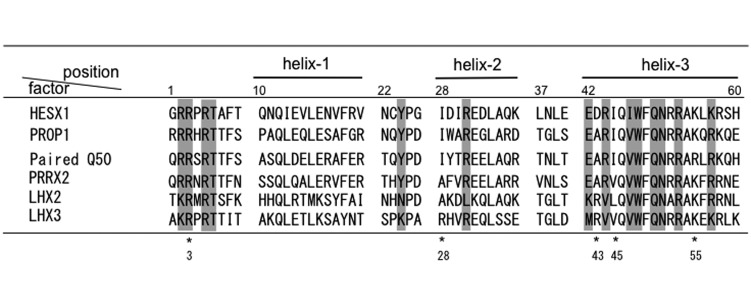

Lhx3 expression during porcine pituitary development

We previously reported a gradual increase in Lhx3-expression during fetal development by RT-PCR [25], which was similar to that of Lhx2-expression [14]. Real-time PCR during porcine pituitary development revealed that the expression of both isoform genes gradually increased before birth, followed by an appreciable decrease by P230 (Fig. 4). The expression level of Lhx3a was approximately 20–100-fold higher than that of Lhx3b in both sexes, and the expression level of Lhx3a and Lhx3b was higher in females than in males.

Fig. 4.

Real-time PCR analysis of Lhx3 mRNAs in porcine anterior pituitaries. Lhx3a (A) and Lhx3b (B) mRNAs of male and female porcine anterior pituitaries were quantified by real-time PCR, and the results are indicated as the relative amounts of Lhx3a and Lhx3b compared to cyclophilin A. Numbers indicated at horizontal axis indicate fetal and postnatal days.

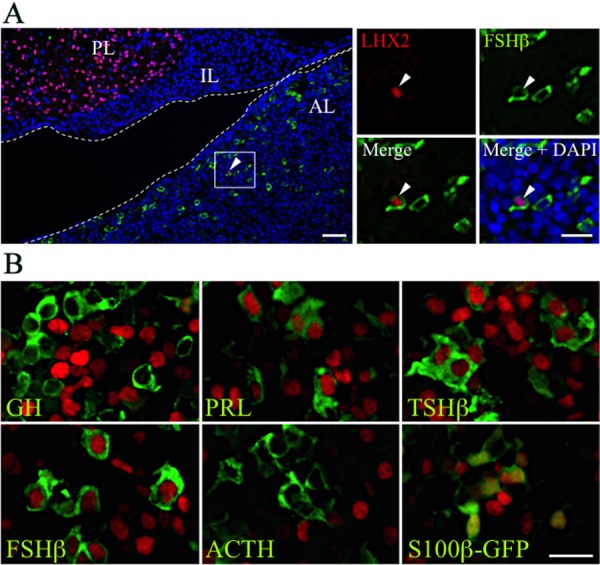

Immunohistochemistry of LHX2 and LHX3

Immunohistochemistry of LHX2 and LHX3 in the postnatal pituitary (P15) was performed using specific antibodies. LHX2-positive cells were not observed in the anterior lobe of the embryonic pituitary. However, a small number of LHX2-positive cells were observed in the postnatal pituitaries, a part of which was the gonadotrope (Fig. 5A), and they were abundant in the posterior lobe but not in the intermediate lobe. In contrast, LHX3-positive cells were observed in the anterior and intermediate lobes, but not in the posterior lobe (data not shown). Double staining with antibodies for hormones and S100β, a non-endocrine cell marker, showed that LHX3 was expressed in most FSHβ-cells as well as in most TSHβ-, PRL-, and S100β-positive cells, but not in GH- and ACTH-positive cells (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemistry of LHX2 and LHX3 in the postnatal pituitary. (A) Double-immunostaining of LHX2 (Cy3, red) and FSHβ (Cy5, green) for section on P15 was performed. Merged image with DAPI (nuclei) is shown in the left panel and boxed areas are enlarged in the right panels. Arrowheads indicate LHX2/FSHβ-double positive cells. Dotted lines indicate Rathke’s cleft. AL, anterior lobe; IL, posterior lobe; PL, posterior lobe. Bars in the left and right panels indicate 50 and 20 µm, respectively. (B) Double-immunostaining of LHX3 (Cy3, red) and pituitary hormones (Cy5, green with false color) or S100β-GFP (FITC, green) for section on P15 were performed. Bar indicates 20 µm.

Discussion

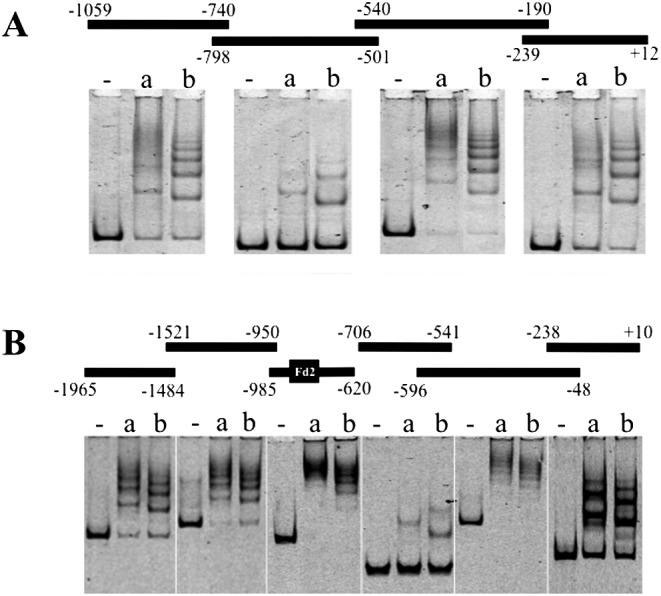

LHX2 and LHX3 belong to the LIM-homeobox family and are composed of two LIM domains (protein-protein interaction) and a homeobox domain (DNA binding domain). Cumulative data have shown that two related factors modulate the gene expression of porcine Fshβ [10, 14] and Cga [8, 35, 36] and sharing their targets. However, the similarity of their amino acid sequences is quite low (approximately 50% similarity in the LIM and homeobox domains, as shown in Fig. 1), raising the question as to whether these proteins have similar functions. Thus, we compared LHX2 and LHX3 activity in the regulation of Cga and Fshβ. Binding and reporter assays demonstrated that LHX2 and LHX3 share similar DNA regions but show differences in binding specificity and transcription activity. However, immunohistochemistry showed that LHX2, but not LHX3, was present in a small number of gonadotropes.

The gel mobility shift assay and DNase I footprinting of LHX2 and LHX3 suggested differences in binding specificities. Tables 1 and 2 summarize the binding sites of LHX2 and LHX3 at the promoter region of Cga and Fshβ. Most sites contained the required core motif, TAAT/ATTA, for homeobox-type transcription factors [16,17,18,19]. We previously verified using the SELEX method that LHX2 and LHX3 showed binding affinity for the hexa-nucleotides TAATTA and T/AA/TT/ATA/TA, respectively [14], and discussed that dissimilarity may have been caused by amino acid differences in the homeodomain, a DNA binding domain composed of 60 amino acids making up three α-helixes [21, 22] (Fig. 6). Two proteins showed only 43% similarity in the homeodomain, with differences in 4 of the 14 amino acids in the essential DNA binding sites, including position 2 (Arg and Lys), position 24 (Asn and Lys), position 31 (Leu and Arg), position 42 (Lys and Met), and position 57 (Arg and Lys), providing variations in polarity, charge, and steric configuration. While Wilson et al. [22] demonstrated that residues at 28 (Ile) and 43 (Ala), which are among the five amino acids fundamental for dimerization, are important for hydrophobic interactions, LHX2 and LHX3 contained different amino acids, indicating that they do not form dimers through the homeodomain, as previously observed for paired related homeobox 2 [37].

Fig. 6.

Comparison of the amino acid sequences of the homeodomains. Amino acid sequences of homeodomain of HESX1 (Accession number: NM_010420) [21, 22], PROP1 (Accession number: AB187272) [23], paired Q50 (Accession number: 1FJL_A) [20], and PRX2 (Accession number: D00584745) [26] are compared with those of porcine LHX2 and LHX3. Amino acid residues important for dimerization and for DNA-binding are marked with an asterisk (*) and shaded, respectively.

The variance in transcriptional activities between LHX2 and LHX3s depend on the cell type (Fig. 3), indicating the presence of cell type-specific interactors with both factors to modify their activities in addition to differences in the transcriptional ability. Indeed, the LIM domain of LHX2 and LHX3 are well-known to interact with different classes of transcription factors and/or co-factors [15, 38]. These complexes are involved in diverse biological functions. Various proteins, including CLIM2/NL1/LDB1 and ISL1 [39], PIT1 [40], SF1 [41], and SLB [41], have been reported to interact with LHX3. Our cumulative research demonstrated that CLIM2, a co-factor, is capable of binding to LHX2 and that the interaction with CLIM2 represses LHX2-dependent stimulation of Cga expression [36]. Furthermore, CLIM2 is known to interact with several types of LIM-only proteins [42], such as single-stranded binding protein 2 (SSBP2) [43], in the pituitary to form a large complex with various transcription factors (TAL1, E47, and GATA-1) and with LMO2 [44,45,46] in other tissues. Additionally, it was reported that LHX2 can recruit a co-activator p300, a TATA-binding protein, through the LHX2-binding protein MRG1 [35]. These various interacting partners make it possible to respond to the diverse demands of gene regulation.

The immunohistochemistry results for LHX2 were unexpected. This factor was first cloned from the pituitary gonadotrope lineage cell line αT3-1 [12] and from the porcine anterior pituitary using a Yeast Two-Hybrid System [14]. In the latter, the LHX2 cDNA clone was obtained through repeated screenings and the LHX3 cDNA clone was never found, indicating a stronger DNA binding ability for LHX2 than for LHX3. Zhao et al. described the absence or barely detectable level of Lhx2 in the embryonic anterior lobe without a description of the postnatal tissue by in situ hybridization [12]. Collectively, LHX2 may be transiently expressed in the gonadotrope as well as in other pituitary cells and regulate Fshβ and Cga by competing with LHX3. In contrast, immunohistochemistry for LHX3 demonstrated that this factor resides in select pituitary cells, including FSHβ-, PRL-, TSHβ-, and S100β-positive cells, in the postnatal adult anterior lobe. How Lhx3 discriminates between cell types remains to be clarified.

In summary, we demonstrated that LHX2 and LHX3s differ in their DNA binding specificities and transcriptional activities. In addition, these proteins showed cell type-dependent activity. The population of LHX2-positive cells was very small, while LHX3s collectively resided in gonadotrope cells. It would be interesting to evaluate the cross-talk between LHX2 and LHX3s in cells expressing both proteins.

Supplementary

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr PL Mellon of the University of California, San Diego, for providing the LβT2 cells. We also thank Dr S Tanaka of Shizuoka University for providing the antibodies to human GH and ACTH and Dr Es Monuki at the University of California for providing the antibodies to LHX2. This work was partially supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Nos. 26292166 to (YK), and 24580435 and 15K07771 (to TK), and by a research grant (A) to YK from the Institute of Science and Technology, Meiji University. Our study was also supported by the ‘High-Tech Research Center’ Project for Private Universities, and a matching fund subsidy, 2008–2010, from the MEXT of Japan and by the Foundation for Growth Science.

References

- 1.Jorgensen JS, Quirk CC, Nilson JH. Multiple and overlapping combinatorial codes orchestrate hormonal responsiveness and dictate cell-specific expression of the genes encoding luteinizing hormone. Endocr Rev 2004; 25: 521–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhu X, Gleiberman AS, Rosenfeld MG. Molecular physiology of pituitary development: signaling and transcriptional networks. Physiol Rev 2007; 87: 933–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moriyama R, Yamazaki T, Kato T, Kato Y. Long-chain unsaturated fatty acids reduce the transcriptional activity of the rat follicle-stimulating hormone β-subunit gene. J Reprod Dev 2016; 62: 195–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sheng HZ, Zhadanov AB, Mosinger B, Jr, Fujii T, Bertuzzi S, Grinberg A, Lee EJ, Huang S-P, Mahon KA, Westphal H. Specification of pituitary cell lineages by the LIM homeobox gene Lhx3. Science 1996; 272: 1004–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sheng HZ, Moriyama K, Yamashita T, Li H, Potter SS, Mahon KA, Westphal H. Multistep control of pituitary organogenesis. Science 1997; 278: 1809–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bach I, Rhodes SJ, Pearse RV, 2nd, Heinzel T, Gloss B, Scully KM, Sawchenko PE, Rosenfeld MG. P-Lim, a LIM homeodomain factor, is expressed during pituitary organ and cell commitment and synergizes with Pit-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995; 92: 2720–2724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Girardin SE, Benjannet S, Barale JC, Chrétien M, Seidah NG. The LIM homeobox protein mLIM3/Lhx3 induces expression of the prolactin gene by a Pit-1/GHF-1-independent pathway in corticotroph AtT20 cells. FEBS Lett 1998; 431: 333–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meier BC, Price JR, Parker GE, Bridwell JL, Rhodes SJ. Characterization of the porcine Lhx3/LIM-3/P-Lim LIM homeodomain transcription factor. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1999; 147: 65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sloop KW, Meier BC, Bridwell JL, Parker GE, Schiller AM, Rhodes SJ. Differential activation of pituitary hormone genes by human Lhx3 isoforms with distinct DNA binding properties. Mol Endocrinol 1999; 13: 2212–2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.West BE, Parker GE, Savage JJ, Kiratipranon P, Toomey KS, Beach LR, Colvin SC, Sloop KW, Rhodes SJ. Regulation of the follicle-stimulating hormone β gene by the LHX3 LIM-homeodomain transcription factor. Endocrinology 2004; 145: 4866–4879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter FD, Drago J, Xu Y, Cheema SS, Wassif C, Huang SP, Lee E, Grinberg A, Massalas JS, Bodine D, Alt F, Westphal H. Lhx2, a LIM homeobox gene, is required for eye, forebrain, and definitive erythrocyte development. Development 1997; 124: 2935–2944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao Y, Mailloux CM, Hermesz E, Palkóvits M, Westphal H. A role of the LIM-homeobox gene Lhx2 in the regulation of pituitary development. Dev Biol 2010; 337: 313–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberson MS, Schoderbek WE, Tremml G, Maurer RA. Activation of the glycoprotein hormone alpha-subunit promoter by a LIM-homeodomain transcription factor. Mol Cell Biol 1994; 14: 2985–2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kato T, Ishikawa A, Yoshida S, Sano Y, Kitahara K, Nakayama M, Susa T, Kato Y. Molecular cloning of LIM homeodomain transcription factor Lhx2 as a transcription factor of porcine follicle-stimulating hormone beta subunit (FSHβ) gene. J Reprod Dev 2012; 58: 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bach I. The LIM domain: regulation by association. Mech Dev 2000; 91: 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catron KM, Iler N, Abate C. Nucleotides flanking a conserved TAAT core dictate the DNA binding specificity of three murine homeodomain proteins. Mol Cell Biol 1993; 13: 2354–2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Damante G, Fabbro D, Pellizzari L, Civitareale D, Guazzi S, Polycarpou-Schwartz M, Cauci S, Quadrifoglio F, Formisano S, Di Lauro R. Sequence-specific DNA recognition by the thyroid transcription factor-1 homeodomain. Nucleic Acids Res 1994; 22: 3075–3083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jagla K, Stanceva I, Dretzen G, Bellard F, Bellard M. A distinct class of homeodomain proteins is encoded by two sequentially expressed Drosophila genes from the 93D/E cluster. Nucleic Acids Res 1994; 22: 1202–1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pomerantz JL, Sharp PA. Homeodomain determinants of major groove recognition. Biochemistry 1994; 33: 10851–10858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson DS, Guenther B, Desplan C, Kuriyan J. High resolution crystal structure of a paired (Pax) class cooperative homeodomain dimer on DNA. Cell 1995; 82: 709–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakayama M, Kato T, Susa T, Sano A, Kitahara K, Kato Y. Dimeric PROP1 binding to diverse palindromic TAAT sequences promotes its transcriptional activity. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2009; 307: 36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato Y, Kimoto F, Susa T, Nakayama M, Ishikawa A, Kato T. Pituitary homeodomain transcription factors HESX1 and PROP1 form a heterodimer on the inverted TAAT motif. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2010; 315: 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aikawa S, Kato T, Susa T, Tomizawa K, Ogawa S, Kato Y. Pituitary transcription factor Prop-1 stimulates porcine follicle-stimulating hormone β subunit gene expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2004; 324: 946–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sloop KW, Dwyer CJ, Rhodes SJ. An isoform-specific inhibitory domain regulates the LHX3 LIM homeodomain factor holoprotein and the production of a functional alternate translation form. J Biol Chem 2001; 276: 36311–36319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Susa T, Ishikawa A, Kato T, Nakayama M, Kitahara K, Kato Y. Regulation of porcine pituitary glycoprotein hormone alpha subunit gene with LIM-homeobox transcription factor Lhx3. J Reprod Dev 2009; 55: 425–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Susa T, Ishikawa A, Kato T, Nakayama M, Kato Y. Molecular cloning of paired related homeobox 2 (prx2) as a novel pituitary transcription factor. J Reprod Dev 2009; 55: 502–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kato Y, Koike Y, Tomizawa K, Ogawa S, Hosaka K, Tanaka S, Kato T. Presence of activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) in the porcine anterior pituitary. Mol Cell Endocrinol 1999; 154: 151–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato T, Kitahara K, Susa T, Kato T, Kato Y. Pituitary transcription factor Prop-1 stimulates porcine pituitary glycoprotein hormone alpha subunit gene expression. J Mol Endocrinol 2006; 37: 341–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alarid ET, Windle JJ, Whyte DB, Mellon PL. Immortalization of pituitary cells at discrete stages of development by directed oncogenesis in transgenic mice. Development 1996; 122: 3319–3329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pernasetti F, Vasilyev VV, Rosenberg SB, Bailey JS, Huang HJ, Miller WL, Mellon PL. Cell-specific transcriptional regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone-beta by activin and gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the LbetaT2 pituitary gonadotrope cell model. Endocrinology 2001; 142: 2284–2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Susa T, Kato T, Kato Y. Reproducible transfection in the presence of carrier DNA using FuGENE6 and Lipofectamine2000. Mol Biol Rep 2008; 35: 313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogawa S, Aikawa S, Kato T, Tomizawa K, Tsukamura H, Maeda K, Petric N, Elsaesser F, Kato Y. Prominent expression of spinocerebellar ataxia type-1 (SCA1) gene encoding ataxin-1 in LH-producing cells, LbetaT2. J Reprod Dev 2004; 50: 557–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Itakura E, Odaira K, Yokoyama K, Osuna M, Hara T, Inoue K. Generation of transgenic rats expressing green fluorescent protein in S-100beta-producing pituitary folliculo-stellate cells and brain astrocytes. Endocrinology 2007; 148: 1518–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mangale VS, Hirokawa KE, Satyaki PR, Gokulchandran N, Chikbire S, Subramanian L, Shetty AS, Martynoga B, Paul J, Mai MV, Li Y, Flanagan LA, Tole S, Monuki ES. Lhx2 selector activity specifies cortical identity and suppresses hippocampal organizer fate. Science 2008; 319: 304–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Glenn DJ, Maurer RA. MRG1 binds to the LIM domain of Lhx2 and may function as a coactivator to stimulate glycoprotein hormone alpha-subunit gene expression. J Biol Chem 1999; 274: 36159–36167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Susa T, Sato T, Ono T, Kato T, Kato Y. Cofactor CLIM2 promotes the repressive action of LIM homeodomain transcription factor Lhx2 in the expression of porcine pituitary glycoprotein hormone alpha subunit gene. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006; 1759: 403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Susa T, Kato T, Yoshida S, Yako H, Higuchi M, Kato Y. Paired-related homeodomain proteins Prx1 and Prx2 are expressed in embryonic pituitary stem/progenitor cells and may be involved in the early stage of pituitary differentiation. J Neuroendocrinol 2012; 24: 1201–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthews JM, Visvader JE. LIM-domain-binding protein 1: a multifunctional cofactor that interacts with diverse proteins. EMBO Rep 2003; 4: 1132–1137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jurata LW, Pfaff SL, Gill GN. The nuclear LIM domain interactor NLI mediates homo- and heterodimerization of LIM domain transcription factors. J Biol Chem 1998; 273: 3152–3157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Granger A, Bleux C, Kottler ML, Rhodes SJ, Counis R, Laverrière JN. The LIM-homeodomain proteins Isl-1 and Lhx3 act with steroidogenic factor 1 to enhance gonadotrope-specific activity of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptor gene promoter. Mol Endocrinol 2006; 20: 2093–2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Howard PW, Maurer RA. Identification of a conserved protein that interacts with specific LIM homeodomain transcription factors. J Biol Chem 2000; 275: 13336–13342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Susa T, Ishikawa A, Cai LY, Kato T, Matsumoto K, Kitahara K, Kurokawa R, Ono T, Kato Y. The highly related LIM factors, LMO1, LMO3 and LMO4, play different roles in the regulation of the pituitary glycoprotein hormone α-subunit (α GSU) gene. Biosci Rep 2010; 30: 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kato Y, Kato T, Ono T, Susa T, Kitahara K, Matsumoto K. Intracellular localization of porcine single-strand binding protein 2. J Cell Biochem 2009; 106: 912–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wadman IA, Osada H, Grütz GG, Agulnick AD, Westphal H, Forster A, Rabbitts TH. The LIM-only protein Lmo2 is a bridging molecule assembling an erythroid, DNA-binding complex which includes the TAL1, E47, GATA-1 and Ldb1/NLI proteins. EMBO J 1997; 16: 3145–3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu Z, Huang S, Chang LS, Agulnick AD, Brandt SJ. Identification of a TAL1 target gene reveals a positive role for the LIM domain-binding protein Ldb1 in erythroid gene expression and differentiation. Mol Cell Biol 2003; 23: 7585–7599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lahlil R, Lécuyer E, Herblot S, Hoang T. SCL assembles a multifactorial complex that determines glycophorin A expression. Mol Cell Biol 2004; 24: 1439–1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.