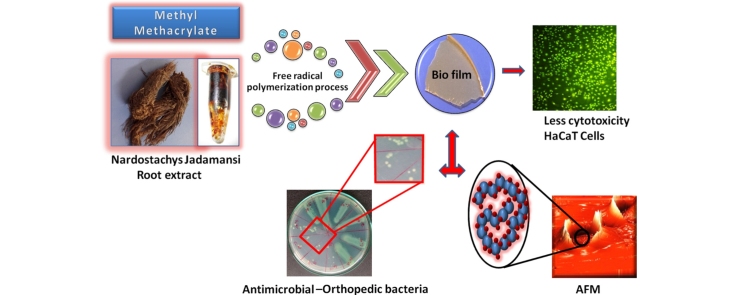

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Nardostachys jatamansi DC., Spikenard, Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), Biocomposite, Cytocompatibility, Atomic force microscopy (AFM)

Highlights

-

•

Polymer biocomposite was successfully synthesized by free radical polymerization technique.

-

•

Biocomposites enhance better antibacterial and antifungal activities against various microorganisms.

-

•

Evaluated the orthopedic infection bacteria by serial dilution method.

-

•

Morphological structure of biocomposite characterized by AFM.

-

•

Exhibit the less in vitro cytotoxicity against HaCaT cells.

Abstract

The present study explores the synthesis of highly potential polymer biocomposite from Nardostachys jatamansi rhizome extract. The polymer biocomposites were synthesized from methyl methacrylate by free radical polymerization. ATR-IR enunciate the functional groups attributed at 956 cm−1 (aromatic), a peak appeared at 1685 cm−1 (—C O), 1186 cm−1 (—O—CH3), 1149 cm−1 (—C—O—C) framework and 1279 cm−1 (—C—O), which are good agreement for the formation composites. The quantitative evaluations of antimicrobial studies were analyzed by serial dilution method and also improved activity in orthopedic infection pathogens. Cytocompatibility was analyzed by keratinocyte cell lines and it may be used for various biomedical applications.

1. Introduction

In recent years microbes have developed resistance and their pathogenic ability was increased due to the repeated use of common commercial drugs by the people for treatment of various diseases. Many research articles have reported that the herbal medicine does not cause any side effect and they are important alternatives to synthetic medicines.1 Nardostachys jatamansi is one of the most popular aromatic medicinal plant and an endangered, therapeutic agent belongs to the family of valerianaceae, locally called spikenard. It is a very rare plant found in Kolli hills and Himalayas in India. N. jatamansi was used in traditional medicines and cosmetic products for centuries.2, 14, 15 More than 25 active potential compounds have been isolated from the rhizomes of plant. The major alkaloids namely jadamonson, nardostachone, coumarins and neoligns are present in this plant.3 N. jatamansi rhizomes are used to treat skin diseases, mental illness, hypertension, epilepsy, cholera, hyperlipidemia and heart diseases.4, 5 Zahida et al.,6 stated that the essential oil of N. jatamansi has potential antimicrobial activity against both gram positive and gram negative bacteria.

Pandey et al.,7 reported that the phenolic acid components are powerful antioxidants and they have several biological activities against bacteria, virus, cancer cells and inflammation.8 Krishna Rao et al.,9 developed a very transparent polymer biocomposite film using this plant rhizome and tested against various fungal pathogens. In these days, we are all depending upon bio-based synthetic materials in all fields especially in medical field.10, 11 The polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) has high mechanical strength and good stable quality and it can be used as a transparent engineering material such as contact lens, tooth resin and bone cement.12 The smooth surface having PMMA microspheres are ideal fillers for soft tissue in cosmetics and reconstructive application.16

Cataract surgery has great attention in order to develop a new posterior capsule opacification after intraocular lenses implantation for cataract lens.17 During cataract surgery, human lens epithelial cells (HLECs) were severely damage. In order to resolve this problem, Wang et al.,18 synthesized a novel poly(hedral oligomeric silsesquioxane-co-methyl methacrylate) copolymer using free radical polymerization technique to promoting the in vitro cytotoxicity of HLECs cells and silver nanoparticles embedded PMMA composites could be used in the field of anti orthopedic infection against Acinetobacter baumannii and methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. This antimicrobial implant material could act as broad spectrum and long intermediate term antimicrobial effect.19, 20, 21

Moreover, PMMA has more biocompatible and it can also enhance better anti-microbial activity.13 With this background the present work was carried out to synthesized Jatamansi-based polymer biocomposite using specific monomer of methyl methacrylate by free radical polymerization technique and the biocomposites was tested against various orthopedic bacterial and fungal pathogens. More particularly, cytotoxicity was done using human keratinocytes cells.

2. Materials and methods

N. jatamansi plant rhizomes were collected from Kolli hills, Namakkal district, Tamil Nadu, India. The rhizomes were separated from plant by cutting washed, shade dried, pulverized into powder form and powder materials were stored in air-tight bottles. The monomer of methyl methacrylate (MMA) with formula of C5H8O2-99% contained ≤30 ppm, monomethyl ether hydroquinone as an inhibitor and radical initiator of benzyl peroxide was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, USA. Keratinocyte cell lines from adult human skin (HaCaT cells) were procured from National Center for Cell Science (NCCS), Pune, India. Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), trypsin-EDTA, fetal bovine serum (FBS), 3-(4,5-dimethyl thiazol-2-yl)-2,5-(diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) (MTT), antibiotic-antimycotic solution, and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich, USA. Chloroform, methanol (CH3-OH), Nutrient agar and broth, Agar Agar type-I, sterile disk, potato dextrose agar and broth were procured from Hi-media for microbiological examination. The bacterial and fungal culture strains were collected from MTCC, Chandigarh, India.

The solution state 13C NMR spectroscopic analysis was recorded on a Bruker Advance III 400 NMR spectrometer (400 MHz, Germany) and the spectra were recorded in CDCl3 solvent. The new JASCO model V-530 UV-vis spectrophotometer (USA) was recorded in chloroform. FT-IR spectra of the polymer composite films were taken using ABB MB3000 Fourier transform infrared spectrometer in ATR mode, 40 scans with resolution of 12 cm−1. Optical microscopy was performed using Olympus BX50 optical polarizing microscope and photograph was taken in an Olympus C7070 using digital camera. The topographical analysis determined by using atomic force microscopy (AFM), conducted in non-contact mode, NT-MDT, NTEGRA Prima, Netherlands. The thermo lab systems multiskan ascent photometer for 96 well plates was used for cell assessment and cell morphological analysis was determined by fluorescence microscopy (DMI-IL LED, Leica, Germany).

2.1. Sample preparation for atomic force microscopy

The rhizome extract based polymer composites (1 mg) was dissolved in chloroform (1 mL) using sonicator for about 2 min. 1 cm2 glass substrates were prepared by diamond cutter and clean the substrate using methanol and acetone in order to avoid dust particles. We preferred non-contact mode, because this mode has advantage that cantilever tip never make contact with sample and it cannot disturb or destroy the sample surface. Most probably, many biological samples could be used in non contact mode in AFM.24 During sample preparation, surface charges surface energy, flatness of substrate and hydrophobicity are crucial role.25 However, 3 μL of compound was taken by using micropipette, transferred onto clean glass substrate and dried at 40 °C under vacuum oven. Operational condition for AFM experiment, set point, scan size and scan speed was adjusted to take better resolution topographical images. The dried glass substrate was used for both AFM and optical microscopy to analyze their morphology.

2.2. Preparation of N. jatamansi rhizome extract

The extraction method is very essential in medicinal plants because of its desired chemical components from plant materials. Here, we describe the basic and simple operational extraction steps include prewashing, drying, grinding to get homogenous materials. First 50 g of N. jatamansi rhizome was taken in a 250 mL of beaker and wash several times with normal tap water to remove soil and dust particles. Again wash with double distilled water about 15 min then completely dried at air atmosphere and kept it in closed room for shadow dry about two weeks. The compound was ground into fine powder and 40 g of bioactive compound was extracted from rhizome by using polar solvent methanol by soxhlet extraction method in the ratio of 1:6 and kept it in shaker for three days at ambient temperature.22, 23 Finally, plant rhizome material was filtered using Whatman filter paper, kept it in vacuum oven for complete drying and stored at 37 °C.

2.3. Preparation of Jatamansi-based polymer composites

The monomer of methyl methacrylate (4 mL) and the radical initiator of benzoyl peroxide (0.05 g) were taken in a double neck round bottom flask. The initiator of benzyl peroxide was dissolved in 3 mL of distilled chloroform. The initiator was added drop by drop using glass syringe to induce the polymerization. Before that nitrogen gas was purged for 30 min and this whole reaction was maintained under nitrogen atmosphere with stirring condition for 3 h at 80 °C. The bioactive compound of N. jatamansi rhizome (3%) extract was dissolved in 3 mL of distilled chloroform and this extract was incorporated once again into the polymerization system for 30 min at ambient temperature. Finally, composite material was removed from oil bath and poured into glass petridish to cast as uniform thickness film.

2.4. Types of microbes and culture conditions

The polymer biocomposite was examined their therapeutic activities by using both gram negative and gram positive bacteria such as Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus aureus, Enterobacter aerogenes, Salmonella paratyphi, Serratia marcescens, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and fungal pathogens namely Malassezia pachydermatis, Aspergillus niger, Trichophyton rubrum, Candida tropicalis and orthopedic infection causing pathogens S. marcescens, E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus and C. tropicalis. Here, the entire microbes were cultured overnight in nutrient agar medium (Hi-media). The prepared microbial inoculum colonies were transferred into 10 mL nutrient broth tube. The microbes containing tubes were shaken for aeration to promote their microbial growth and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h.27

2.5. Determination of minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC)

Human bacterial pathogens S. pneumoniae, E. aerogenes, S. paratyphi and Streptococcus aureus and pathogenic fungi such as M. pachydermatis, T. rubrum, A. niger and C. tropicalis were used for testing. In addition, orthopedic infection pathogen of S. marcescens, E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus were used for MBC. All the microbial cultures were maintained at 4 °C on nutrient agar and potato dextrose agar (PDA) respectively. The MIC of PMMA, N. jatamansi rhizome extract and biocomposite were determined by serial dilution method. The PMMA (200 mg), N. jatamansi rhizome extract (200 mg) and biocomposite materials (200 mg) were dissolved in chloroform and DMSO in concentration 200 mg/mL were mixed with nutrient broth (for bacteria) and potato dextrose broth (for fungi), then 100 μL of test inoculums were added into each tube (10−1 to 10−10 dilution). The final concentration of PMMA, rhizome extract and biocomposite ranged from 0.1 to 40 mg/mL and test tubes were incubated at 37 ± 2 °C for 24–48 h by downstream dilution. The MIC defined as the lowest concentration of antimicrobial that inhibited the growth of microorganism of the incubation was defined as turbidity nature, which clearly indicate the bacterial/fungal growth and plain PMMA was used as control. While fungal inoculums were prepared from 5 to 7 days from fresh fungal culture and standardized to 105 spores/mL and the tubes were incubated at 28 °C for 2–7 days. Additionally, all microorganism were transferred on agar and PDA plates in order to check the minimal bacterial/fungal concentration reveals the lowest concentration of antimicrobial that control the growth of organism after subculture on to antimicrobial free media.28 All measurements were performed as in triplicate.

2.6. Statistical analysis

All the experimental results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation analysis was performed by using Microsoft office excel-2010 for plotting the diagrams from triplicate statistical datas.26

2.7. Cell culture and cytotoxicity assay

HaCaT cell lines were maintained in DMEM with supplement of 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 μg/mL of penicillin and streptomycin at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.31 After reached the 80% confluent, cells were harvested by using 0.25% trypsin-EDTA. Cell count was done by heamocytometer, 1 × 105 cells/mL medium were seeded in 24-well plate contains different concentration of PMMA and 3% of polymer biocomposites (10–30 μg) were incubated up to 24 h and experiments was done in triplicates.

The cytotoxicity45, 46 of polymer biocomposites was evaluated by using standard MTT assay. Tetrazolium salt were prepared in PBS of 1 mg/mL concentration, 100 μL of MTT solution were added into each well plates and incubated at 37 °C for 3 h at dark condition. After incubation formazan crystals were formed and dissolved by using DMSO, purple color of dissolved formazan solution was transferred into 96 micro well plates.32 The absorbance values were read at 540 nm and calculated with standard formula. The cell attachment and morphological analysis was confirmed by fluorescence microscope stained with 100 μg of acridine orange and ethidium bromide (1:1), images were captured by using LEICA microsystem (Germany).

3. Results

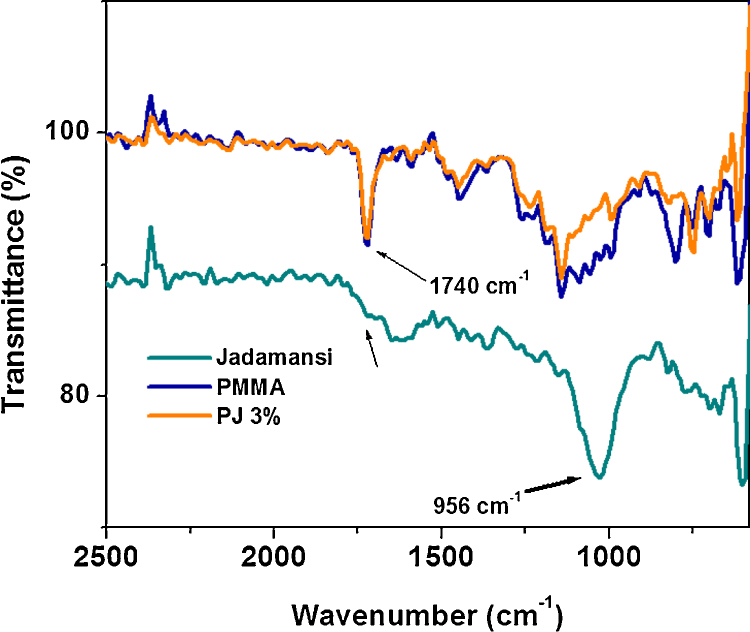

3.1. Investigation of polymer biocomposites using ATR-FTIR and UV–vis spectroscopy

Attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infra-red (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to characterize the functional groups and their structure on PMMA and composites. N. jatamansi had specific peak at 956 cm−1 corresponds to aromatic and alkanes structure of C—H, C—H(CH2) frequency, which was absent in PMMA and polymer biocomposite. This major difference indicates that the aromatic plant rhizome extract absolutely interacted with polymer matrix. The control PMMA and composites were further analyzed by ATR-IR to identify their functional group. A strong new peak at 956 cm−1 was observed and this new peak assigned for N. jatamansi. This peak corresponds to aromatic —C—H stretching and it was not present in polymer composites, which indicated that the plant rhizome extract was well dispersed in polymer matrix (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

ATR-IR spectra for (a) Nardostachys jatamansi rhizome, (b) PMMA, and (c) PJ (3%).

Furthermore, stretching vibration at 743 cm−1 corroborate to strong interaction with methylene stretch at 852 cm−1 (CH2), which are indicate the polymer network backbone.33

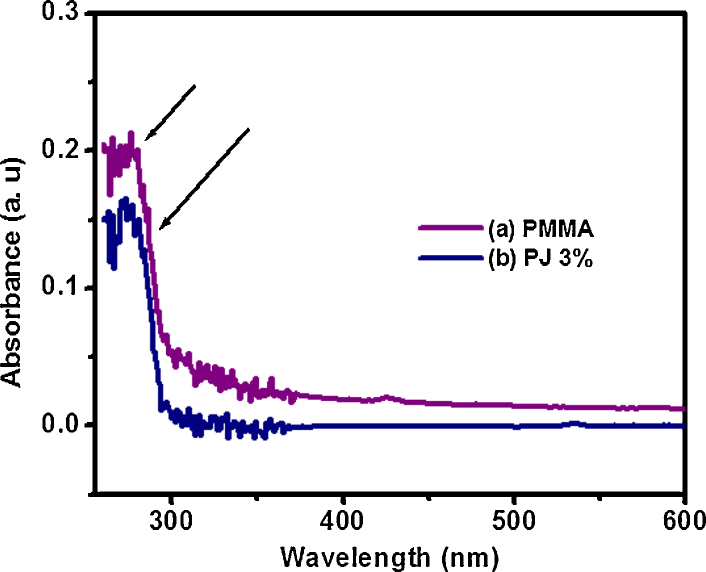

UV-visible spectrophotometer is a consistently used for quantitative determination of different analyses to find out the maximum wavelength region. The absorbance value ∼0.18 at 274–279 nm increases with increase the concentration of N. jatamansi (3%) onto PMMA, which indicate that PMMA is a saturated aliphatic polymer with a carbonyl group as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

UV–vis spectra of (a) PMMA and (b) polymer biocomposite (PJ 3%).

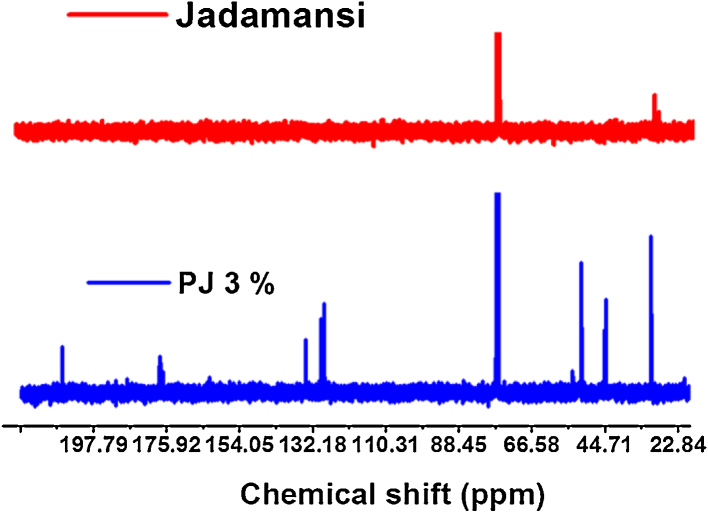

The 13C NMR spectroscopy is one of the important tools to identify the carbon atoms in an organic molecule.34 The NMR spectra were obtained on Bruker Advance III 400 NMR spectrometer and all the spectra were recorded in CDCl3 solvent. The 13C NMR spectra (400 MHz, CDCl3, δ, ppm) of polymer biocomposites and N. jatamansi are showed in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

13C NMR spectra of (a) Nardostachys jatamansi rhizome and (b) PJ (3%).

3.2. Morphological study

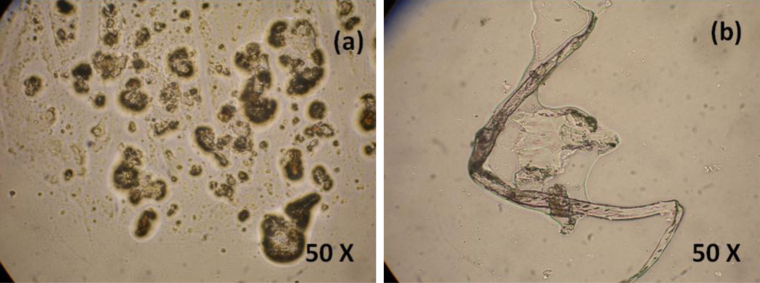

The morphological structure of N. jatamansi and polymer biocomposites (3%) was analyzed by polarized optical microscopy. It is simple techniques that could illumination of sample with polarized light to get bright and original color images.

We observed that some spherical structures are present on plant rhizome extract. The pristine PMMA polymer shows tube like structure. Both structures were able to see in optical microscopy as shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Optical microscopic images of (a) Nardostachys jatamansi rhizome and (b) PJ 3%.

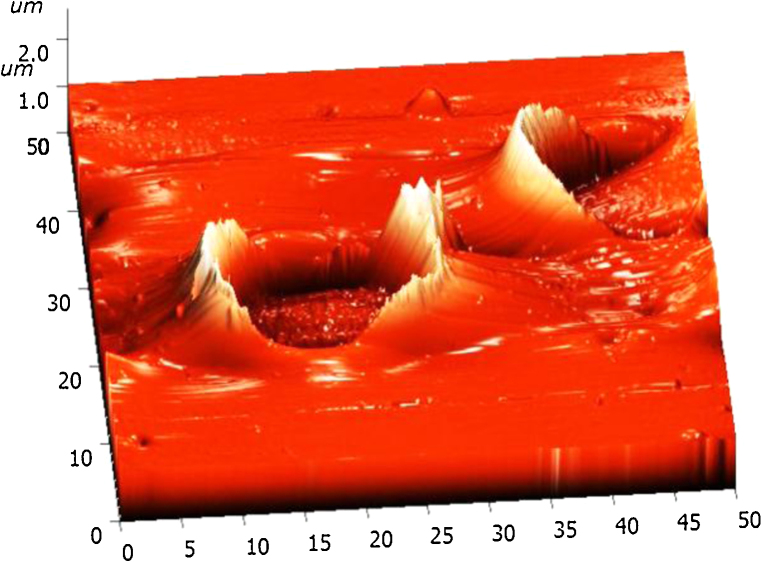

3.3. Atomic force microscopy study (AFM)

Apart from optical microscope studies, the high resolution types of atomic force microscope (AFM) clearly demonstrated the polymer composites. The AFM is a highly used scientific tool for high capability of characterized by surface structure image manipulated matter at nano scale stage. Further AFM provided three-dimensional surfaces and does not require any special treatment such as carbon coating and metal coating. However, the rhizome extract based polymer composites was dissolved in chloroform using sonicator and transferred on clean glass substrate.

AFM operated in non-contact mode to get better high resolution topographical image without any disturbing on sample surface and in this mode tip never contact with sample.24, 25 Fig. 5 shows the AFM topographical image of 3% biocomposite has clearly shows ring well-like structure, which denotes that polymer is surrounding the plant rhizome extract and may be concluded that plant rhizome extract was well interact with polymer matrix.

Fig. 5.

Atomic force microscope image of Nardostachys jatamansi-based polymer biocomposites.

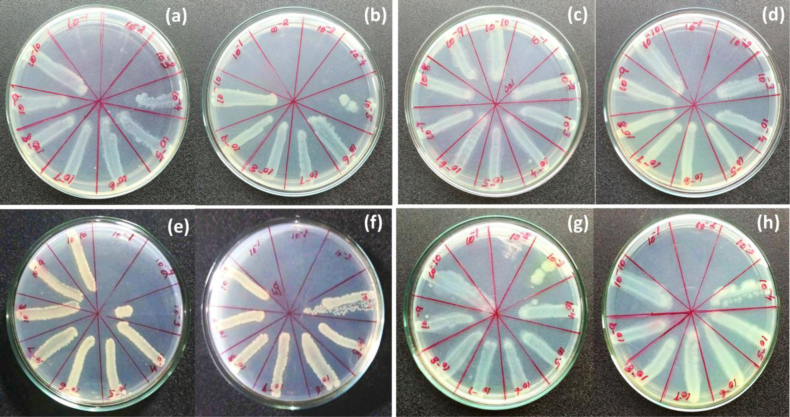

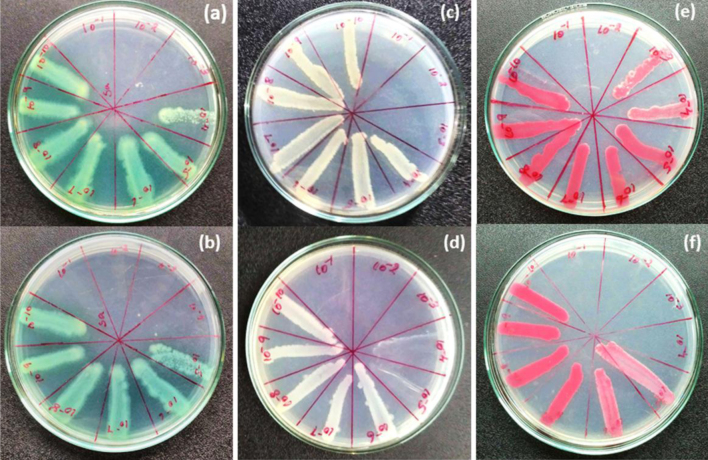

3.4. Minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) analysis of polymer biocomposite and plant rhizome extract

The minimum bactericidal concentration was done by downstream serial dilution method using polymer and rhizome extract on fresh culture of S. pneumoniae, E. aerogenes, S. paratyphi and Streptococcus aureus. These cultures were equally added in 10−1 to 10−10 dilution and after 24 h cultures were streaking into agar plate in order to determine their minimum bacterial inhibition was analyzed as shown in Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Minimum bactericidal concentration of (a) plant rhizome extract, (b) biocomposite in (Streptococcus pneumoniae), (c) plant rhizome extract, (d) biocomposite in (Salmonella paratyphi), (e) plant rhizome extract, (f) biocomposite in (Enterobacter aerogenes), (g) plant rhizome extract, and (h) biocomposite in (Streptococcus aureus).

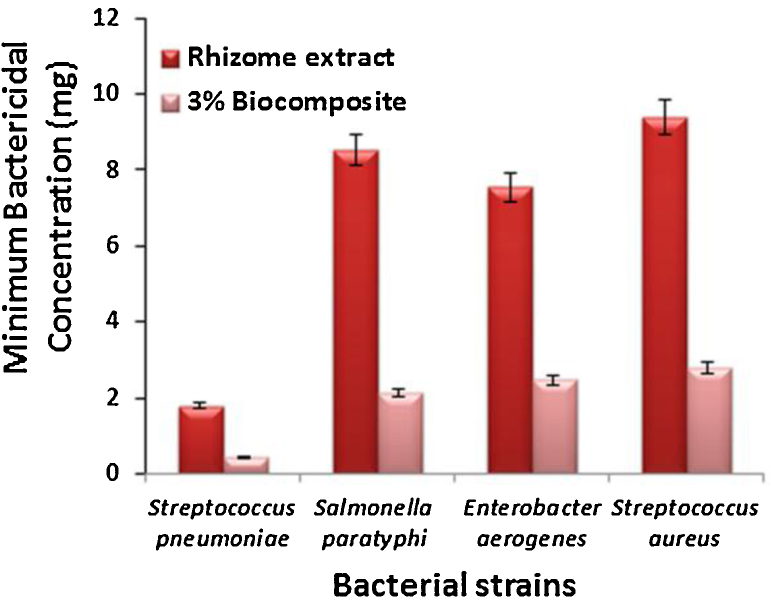

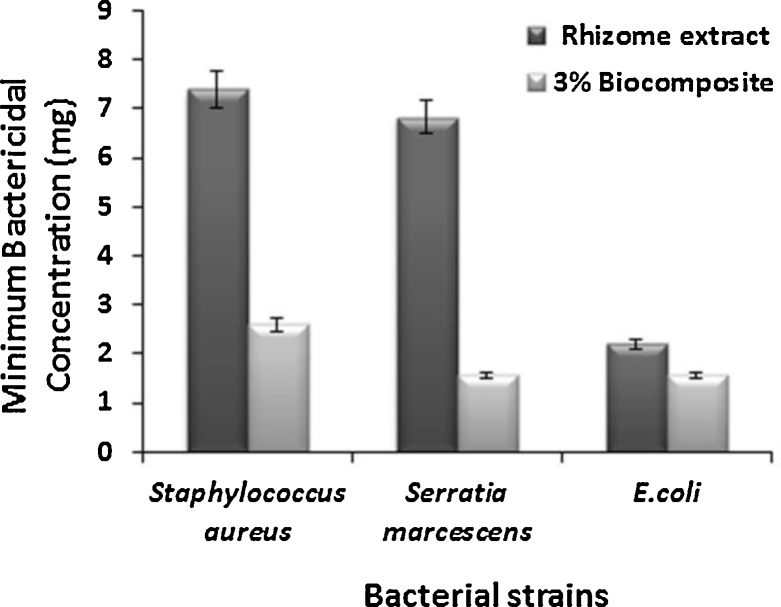

Polymer biocomposite (3%) and rhizome extract were tested their MBC against the gram negative and gram positive bacteria such as [MIC: composite (3%) and rhizome extract] S. pneumoniae (MIC: 10−4, 10−3), E. aerogenes (MIC: 10−3, 10−2), Streptococcus aureus (MIC: 10−3, 10−2) and S. paratyphi (MIC: 10−2, 10−1) as shown in Fig. 7. Also orthopedic infection pathogen of S. marcescens (MIC: 10−4, 10−2), E. coli (MIC: 10−4, 10−3), Staphylococcus aureus (MIC: 10−4, 10−3) was determined their minimum bacterial concentration growth as shown in Fig. 10. In addition, plain PMMA was tested for MIC using above mentioned microbes as shown in Table 1 and ESI (Figs. S1–S3).

Fig. 7.

Bar charts represent the minimum bactericidal concentration of Streptococcus pneumoniae, Salmonella paratyphi, Enterobacter aerogenes, Streptococcus aureus.

Fig. 10.

Orthopedic pathogens of minimum bactericidal concentration of (a) plant rhizome extract, (b) biocomposite in (Staphylococcus aureus), (c) plant rhizome extract, (d) biocomposite in (E. coli), (e) plant rhizome extract, and (f) biocomposite in (Serratia marcescens).

Table 1.

The MIC (MBC & MFC) values of plant rhizome extract and 3% of biocomposite against the test microorganisms as compared to the control PMMA activity.

| Microbial species | Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), mg/mL |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control PMMA (mg/mL) | Plant rhizome extracts (mg/mL) | 3% of biocomposite (mg/mL) | |

| Bacterial strain | |||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 9.8 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.23 | 0.44 ± 0.41 |

| Salmonella paratyphi | 39.92 ± 1.5 | 37.6 ± 0.92 | 7.8 ± 0.61 |

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 40.02 ± 0.5 | 7.55 ± 0.5 | 1.86 ± 0.75 |

| Streptococcus aureus | 37.38 ± 0.5 | 8.74 ± 1.5 | 1.63 ± 0.43 |

| Osteomyelitis strain | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 39.88 ± 0.4 | 6.83 ± 0.2 | 1.6 ± 0.14 |

| Serratia marcescens | 40.0 ± 1.1 | 7.8 ± 0.18 | 0.62 ± 0.08 |

| Escherichia coli | 9.93 ± 0.5 | 1.90 ± 0.06 | 0.76 ± 0.02 |

| Fungal strain | |||

| Candida tropicalis | 40.3 ± 1.1 | 0.51 ± 0.2 | 0.32 ± 0.1 |

| Malassezia pachydermatis | 39.68 ± 0.6 | 1.87 ± 0.35 | 1.48 ± 0.37 |

| Trichophyton rubrum | 39.98 ± 0.05 | 1.69 ± 0.28 | 1.6 ± 0.2 |

| Aspergillus niger | 7.89 ± 0.5 | 0.83 ± 0.4 | 0.08 ± 0.4 |

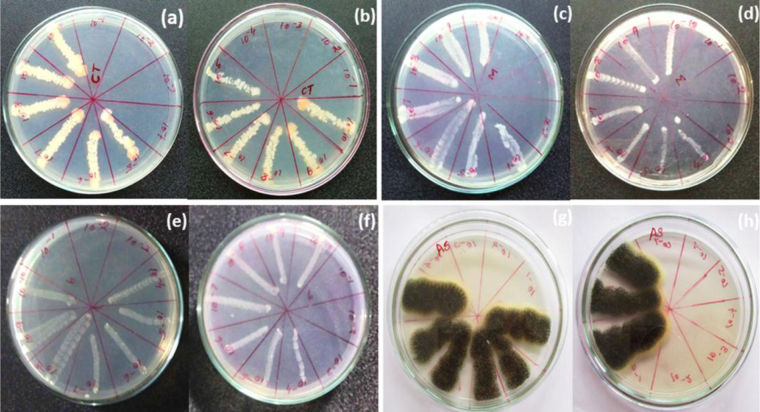

3.5. Minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) analysis of polymer biocomposite and rhizome extract

The minimum fungicidal concentration of polymer biocomposite and plant rhizome extract were analyzed by downstream serial dilution method (10−1 to 10−10) [MIC: composite (3%) and rhizome extract] using M. pachydermatis (MIC: 10−3, 10−3), T. rubrum (MIC: 10−3, 10−3), A. niger (MIC: 10−7, 10−4) and C. tropicalis (MIC: 10−4, 10−4) to determined their minimum bacterial concentration growth on plant rhizome extract and composite was analyzed consciously as shown in Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Minimum fungicidal concentration of (a) plant rhizome extract, (b) biocomposite in (Candida tropicalis), (c) plant rhizome extract, (d) biocomposite in (Malassezia pachydermatis), (e) plant rhizome extract, (f) biocomposite in (Trichophyton rubrum), (g) plant rhizome extract, and (h) biocomposite in (Aspergillus niger).

3.6. Cytotoxicity studies of polymer biocomposite

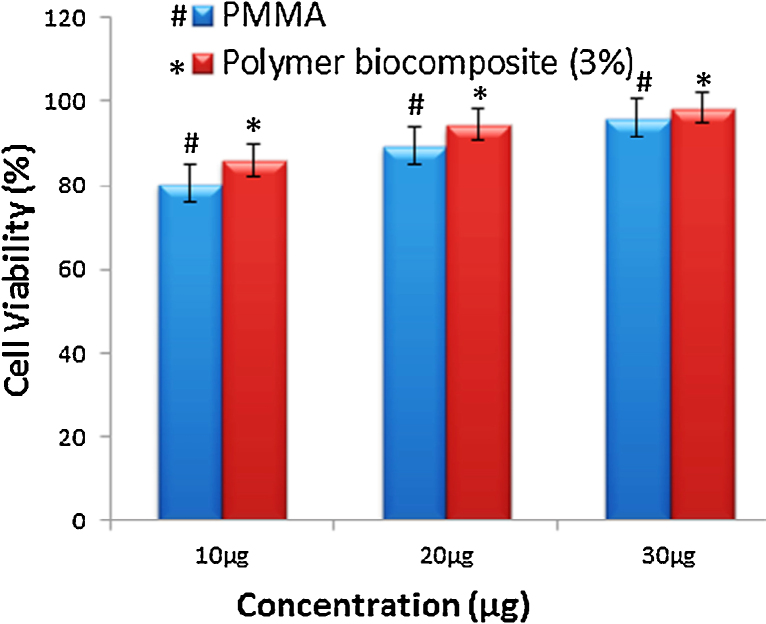

Mendes et al., reported, the PMMA was examined for toxicity against human leukemic cell strain K562 and did not exhibit any adverse effect on cell viability.35 The MTT assay carried out to measure the percentages of cell viability29 (HaCaT cells) on polymer biocomposites by varying concentration (10–30 μg) reveals the cell metabolic activity. The presence of N. jatamansi plant rhizome extract on polymer matrix could enhances cytocompatibility44 and increase the cell population compared to neat PMMA. 1 × 105 cells/mL medium were seeded in 24-well plate contains different concentration of PMMA and 3% of polymer biocomposites (10–30 μg) were incubated up to 24 h. Cell count was examined by heamocytometer to determine the cell cytotoxicity.

4. Discussion

N. jatamansi based polymer composite, plant extract and PMMA were characterized by ATR-IR to determine their functional groups as well as formation of biocomposites as shown in Fig. 1. The spectrum of PMMA (Fig. 1b) contained a sharp peak appeared at 1685 cm−1 indicates the presence of ester carbonyl group (—C O),36, 37 further carbonyl stretching vibration shifted at 1734 cm−1 for polymer biocomposite, which clearly indicate their comparable difference in shift (49 cm−1) for composite and a peak at 1186 cm−1 corresponds to —O—CH3 stretching vibration. Further, additional vibrational peak at 1149 cm−1 (—C—O—C) framework and 1279 cm−1 (—C—O) respectively,38 which are clear evidence for formation of polymethyl methacrylate and biocomposite.

However, we have used 3% of rhizome extract materials in the preparation of polymer composites, because at this concentration it exhibits better biological therapeutic activities. The polymerization reaction was carried out for 3 h at 80 °C under nitrogen atmosphere and the sample was formed as transparent film, size of the samples ∼1.5 mm thickness. The completeness of reaction was identified by ATR-IR spectroscopy, whereas characteristic peak at 1630 cm−1 (C C) is disappearing in MMA polymerization, which indicates that there is no unreacted monomer.39 This polymerization process is not exothermic reaction, its endothermic reaction, moreover this polymerization system heating is absorbing not releasing.

PMMA also exhibit slight antimicrobial properties by disrupting cell membranes40 and implant infection pathogen tested on plain PMMA. It has exhibit less therapeutic activity compared with biocompoiste.41 Although, there is no unreacted monomer present in the polymer as evidence in Fig. 1. In UV–vis spectroscopy was analyzed λmax values of composite materials. The absorption band for carbonyl group is having in the state of n-π* transition. The low intensity absorption band at 274 nm was observed in polymer network and this may be due to the n-π* transition having carbonyl group present in PMMA molecule as well as composites.42 Fig. 2 show the wavelength region of λmax and observed a value at 270 nm that resembles N. jatamansi compounds. In the λmax peak value at 274–279 nm, some shift was observed while increasing concentration of N. jatamansi, which clearly showed good agreement for interaction between N. jatamansi and polymer. This biomolecule contains π-electrons, it could be absorbing some energy in the form of UV light. In this case N. jatamansi plant had longer wavelength region and absorbed more energy.

However, the polymer composites did not absorb expected energy because the plant was completely decorated onto PMMA polymer. In addition, chemical shift at 135 ppm corresponds to aromatic group and 32 ppm assigned —CH3—CO— groups and 32, 75, 135 and 198 ppm correspond to alkynes, —CH3—CO—, aromatic and carbonyl groups, respectively. In addition, 17 ppm corresponds to —CH3 was observed in the composite as shown in Fig. 3.

These are clear evidence for the formation of PMMA based biocomposite. In particular, 13C NMR study reveals better agreement to identify the polymer structures as well as chemical composition present in the plant rhizome extract. In addition, optical and AFM images provide clear evidence for the polymer biocomposite morphological structure, it exhibit well like structure and polymer is wrapping on plant extract. In optical microscopic images afford a tube like structure for PMMA and plant extract were appeared as spherical as shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5. However, this polymer biocomposite materials could act as biomimic to several therapeutic properties and it exhibits very less cytotoxic to human keratinocytes cells, which could be useful for biomedical application. This synthetic polymer is inexpensive and easy to prepare, allow to product on various implant infection. In this work, we currently focused on cytotoxicity for human keratinocytes cells, antifungal, antibacterial activities in various human pathogens by using PMMA based composites, because PMMA is biologically compatible in nature.

The minimum inhibitory concentration is reveals lowest concentration of the test materials that could inhibit growth of pathogens. Determination of MIC is very crucial role in the field of various diagnostic laboratory and research institutes because this kind of method is to identify resistance of microbial pathogens to antimicrobial agent. Further, MBC and MFC were determined by downstream dilution (MIC) method. Moreover, lowest concentration of polymer biocomposite and N. jatamansi completely killed the bacterial and fungal species respectively.30

Orthopedic infections are more resistance to antibiotics in standard therapy, however, we have analyzed the MIC against orthopedic infection bacteria and it was shows minimum growth inhibitory concentration at various dilutions. However, plant rhizome extract were tested their MBC against S. pneumoniae MIC value 1.8 ± 0.23 mg/mL at 10−3 dilution for plant rhizome extract and MIC: 0.44 mg/mL at 10−4 dilution for polymer biocomposite respectively.

E. aerogenes (MIC: 7.55 ± 0.5 mg/mL at 10−2 for extract, 2.46 ± 0.75 mg/mL at 10−3 for composite), MIC: 9.4 ± 1.5 mg/mL at 10−2 dilution for plant extract, 2.8 ± 0.43 mg/mL at 10−3 dilution for composite against Streptococcus aureus. MIC: 36.6 ± 0.92 mg/mL at 10−1 dilution for plant extract, 7.8 ± 0.61 mg/mL at 10−2 dilution for composite against S. paratyphi as shown in Fig. 7.

In addition, S. marcescens MIC value 6.83 ± 0.9 mg/mL at 10−2 for extract and MIC value 1.2 ± 0.2 mg/mL at 10−4 for composite. MIC value 2.2 ± 0.58 mg/mL at 10−3 for extract, 1.04 ± 0.2 mg/mL at 10−4 for composite against E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus 7.4 ± 0.45 mg/mL at 10−3 for extract, 2.6 ± 0.24 mg/mL at 10−4 for composite as shown in Fig. 11.

Fig. 11.

Bar chart represents orthopedic pathogens of minimum bactericidal concentration of Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli, Serratia marcescens.

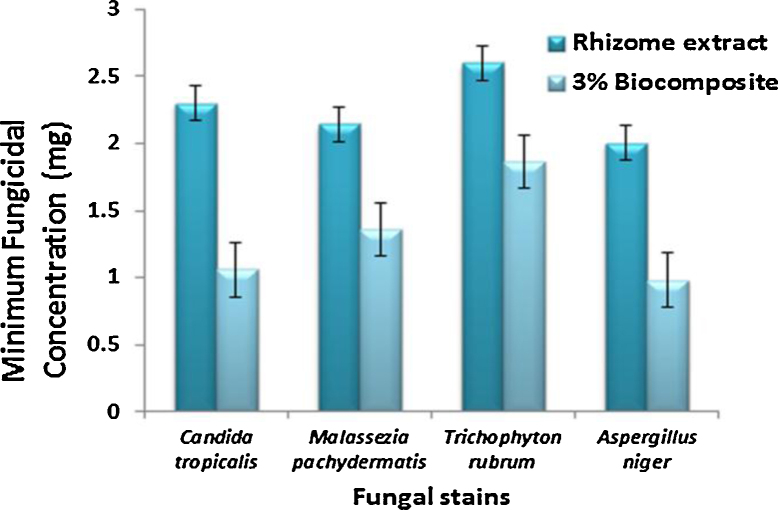

C. tropicalis (MIC: 0.51 ± 0.2 mg/mL at 10−4 for extract and MIC: 0.32 ± 0.1 mg/mL at 10−4 for composite), A. niger (MIC: 0.83 ± 0.4 mg/mL at 10−4 for extract, 0.08 ± 0.4 mg/mL at 10−7 for composite), M. pachydermatis (MIC: 1.87 ± 0.35 mg/mL at 10−3 extract and 1.48 ± 0.37 for composite) and T. rubrum (MIC: 1.69 ± 0.28 mg/mL at 10−3 for extract and 1.6 ± 0.2 for composite) as shown in Fig. 9.

Fig. 9.

Bar chart represents the minimum fungicidal concentration of Candida tropicalis, Malassezia pachydermatis, Trichophyton rubrum, Aspergillus niger.

From the downstream serial dilution results concluded that minimum inhibition concentration [MBC, MFC] was control their microbial growth with lowest value at different species and dilution. The polymer biocomposite values (MIC) are lower than N. jatamansi, which means that the combination of plant rhizome extract and PMMA could enhances their antibacterial and antifungal properties against different pathogenic organism including orthopaedic48, 49, 50 infection pathogens as shown in Table 1.

The cell viability test was analyzed by MTT assay for PMMA and biocomposite. The percentage viability of PMMA was found (10 μg: 80.34%; 20 μg: 89.45%; 30 μg: 95.99%) respectively, whereas polymer biocomposites (3%) exhibit (10 μg: 86.08%; 20 μg: 94.48%; 30 μg: 98.40%). From the experimental results, it is clear evidence for the cell cytocompatibility increase with increase concentration (up to 30 μg) of polymer biocomposite as shown in Fig. 12.

Fig. 12.

Bar chart represents the percentage of cell viability of PMMA (#) and 3% of polymer biocomposite (*) in HaCaT cells.

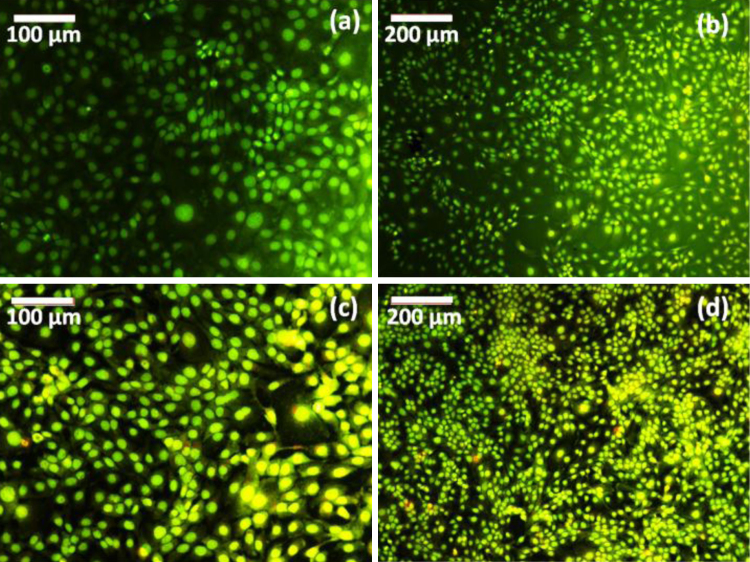

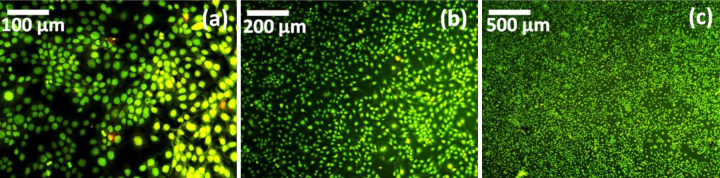

In addition, cell morphological analysis was done by florescence microscope, which shows that HaCaT cells are grown well with uniform alignment on neat PMMA and polymer biocomposite as shown in Fig. 13. From the microscopic image reveals the cells are more viability than neat PMMA after 24 h of incubation period, it emitted green fluorescence indicate the living cells. In addition, Fluorescence images were taken at different cell proliferation region of polymer biocomposite as shown in Fig. 14.

Fig. 13.

Fluorescence microscopic images of (a, b) PMMA and (c, d) 3% of polymer biocomposite.

Fig. 14.

Fluorescence microscopic images of (a–c) 3% of polymer biocomposite at different cell proliferation region.

The overall cytotoxicity47 analysis reveals that could favor more cytocompatibility against HaCaT cells. Overall cellular activities and microstructural architecture of polymer biocomposites plays an important role in cell proliferation. Moreover, the cytotoxicity of this biocomposites did not show any adverse effect leading to cell death.43 From our observation results suggest that the beneficial features of this polymer biocomposites more appropriate for biological and medical application.

5. Conclusions

The present study, N. jatamansi biopolymer was successfully synthesized by free radical polymerization technique using radical initiator of benzoyl peroxide. The polymer biocomposites exhibit better antibacterial and antifungal activities against various microorganisms namely S. pneumoniae, S. paratyphi, M. pachydermatis, T. rubrum and A. niger. A few orthopedic infection pathogens evaluated on biocomposite and plant rhizome extract against S. marcescens (MIC: 10−4, 10−2), E. coli (MIC: 10−4, 10−3), Staphylococcus aureus (MIC: 10−4, 10−3) and C. tropicalis (MIC: 10−4, 10−4) was determined their minimum bacterial concentration growth and this quantitative examination was done by serial dilution method and enhanced their bio-mimicking properties against different pathogens. ATR-IR, NMR, UV–vis spectroscopy results reveals to confirm the structure of PMMA and biocomposite. Morphological structures of polymer biocomposite were identified through optical, fluorescence and AFM microscopic techniques. In addition, this polymer biocomposite exhibit less in vitro cytotoxicity against human keratinocyte cells (HaCaT cells) by using MTT assay. More particularly, these polymer biocomposites could be used for the treatment of various skin diseases, orthopedic infections and it could mimic to excellent herbal based bone cements.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgements

The first author (SP) acknowledges to the University Grants Commission (UGC), India, Grant No. RGNF-2015-17-SC-TAM-14030 for Rajiv Gandhi National Fellowship. The authors wish to thank Rev. Dr. Joseph Antony Samy, Principal and Prof. Antoine Lebel, Head of the Department, Plant Biology and Biotechnology, Loyola College for their support and encouragements.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.jor.2016.04.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Poja B., Sheema B., Leena S., Anupma M., Sunita D. Antibacterial activity and chemical composition of essential oils of ten aromatic plants against selected bacteria. Int J Drug Dev Res. 2012;4:342–351. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Airi S., Rawal R.S., Dhar U., Purohit A.N. Assessment of availability and habitat preference of Jatamansi – a critically endangered medicinal plant of west Himalaya. Curr Sci. 2000;79:1467–1470. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venkatachalapathy V., Balakrishnan S., Musthafa M., Natarajan A. A clinical evaluation of Nardostachys jatamansi in the management of essential hypertension. Int J Pharm Phytopharmacol Res. 2012;2:96–100. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Subashini R., Gnanapragasam A., Senthilkumar S., Yogeeta S.K., Devaki T. Protective efficacy of Nardostachys jatamansi (Rhizomes) on mitochondrial respiration and lysosomal hydrolases during doxorubicin induced myocardial injury in rats. J Health Sci. 2007;53:67. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagchi A., Oshima Y., Hikino H. Validity of oriental medicines 142. Neolignans and lignin's of Nardostachys jatamansi roots. Planta Med. 1991;57:96–97. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-960037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zahida P., Saima S., Muafia S., Shaista J.K., Razia K. Volatile constituents: antibacterial and antioxidant activity of essentials oil from Nardostachys Jatamansi DC. roots. Pharmacology. 2011;3:329–337. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pandey M.M., Katara A., Pandey G., Rastogi S., Rawat A.K.S. An important Indian traditional drug of ayurveda Jatamansi and its substitute bhootkeshi: chemical profiling and antioxidant activity evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;8:1–2. doi: 10.1155/2013/142517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naveen P., Kumari N.S., Sanjeev G., Gowda K.M., Madhu L.N. Radioprotective effect of Nardostachys jatamansi against whole body electron beam induced oxidative stress and tissue injury in rats. J Pharm Res. 2011;4:2197–2200. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krishna Rao K.S.V., lldoo C., Mallikarjuna R.K., Chang-Sik H. PMMA-based microgels for controlled release of an anticancer drug. J Appl Polym Sci. 2009;111:845–853. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaborowska M., Welch K., Branemark R., et al. Bacteria-material surface interactions: methodological development for the assessment of implant surface induced antibacterial effects. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2015;103:179–187. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keaton Smith J., Bumgardner J.D., Courtney H.S., Smeltzer M.S., Haggard W.O. Antibiotic-loaded chitosan film for infection prevention: a preliminary in vitro characterization. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2010;94:203–211. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arabmotlagh M., Bachmaier S., Geiger F., Rauschmann M. PMMA-hydroxyapatite composite material retards fatigue failure of augmented bone compared to augmentation with plain PMMA: in vivo study using a sheep model. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2014;102:1613–1619. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.33140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gebremedhin S., Dorocka-Bobkowska B., Prylinski M., Konopka K., Duzgunes N. Miconazole activity against Candida biofilms developed on acrylic discs. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;65:593–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Priya S., Jeya Jothi G. Influence of Nardostachys jatamansi DC. into transparent polymer biocomposites for in-vitro fungal efficacy. IOSR J Pharm Biol Sci. 2014;9:44–48. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh A., Kumar A., Duggal S. Nardostachys jatamansi DC. potential herb with CNS effects. Asian J Pharm Res Health Care. 2009;1:276–290. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morhenn V.B., Lemperle G., Gallo R.L. Phagocytosis of different particulate dermal filler substances by human macrophages and skin cells. Dermatol Surg. 2002;28:484–490. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4725.2002.01273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang B., Lin Q., Shen C., Tang J., Han Y., Chen Y.H. Hydrophobic modification of polymethyl methacrylate as intraocular lenses material to improve the cytocompatibility. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;431:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2014.05.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang B., Lin Q., Shen C., Han Y., Tang J., Chen H. Synthesis of MA POSS–PMMA as an intraocular lens material with high light transmittance and good cytocompatibility. RSC Adv. 2014;4:52959–52966. doi: 10.1039/d3ra90083e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li N., Chen X., Zhang J., et al. Effect of AcrySof versus silicone or polymethyl methacrylate intraocular lens on posterior capsule opacification. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:830–838. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng J.W., Wei R.L., Cai J.P., et al. Efficacy of different intraocular lens materials and optic edge designs in preventing posterior capsular opacification: a meta-analysis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:428–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.11.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oei J.D., Zhao W.W., Chu L., et al. Antimicrobial acrylic materials with in situ generated silver nanoparticles. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2012;100:409–415. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karkada G., Shenoy K.B., Halahalli H., Karanth K.S. Nardostachys jatamansi extract prevents chronic restraint stress-induced learning and memory deficits in a radial arm maze task. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2012;3:125–132. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.101879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gottumukkala V.R., Annamalai T., Mukhopadhyay T. Phytochemical investigation and hair growth studies on the rhizomes of Nardostachys jatamansi DC. Pharmacogn Mag. 2011;7:146–150. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.80674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moreno-Herrero F., Colchero J., Gomez-Herrero J., Baro A.M. Atomic force microscopy contact, tapping, and jumping modes for imaging biological samples in liquids. Phys Rev E. 2004;69:031915. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.69.031915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martin Y., Williams C.C., Wickramasinghe H.K. Atomic force microscope-force mapping and profiling on a sub 100-Å scale. J Appl Phys. 1987;61:4723–4729. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alberto M.R., Rinsdahl Canavosio M.A., Manca de Nadra M.C. Antimicrobial effect of polyphenols from apple skins on human bacterial pathogens. Electron J Biotechnol. 2006;9:205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cho K.H., Park J.E., Osaka T., Park S.G. The study of antimicrobial activity and preservative effects of nanosilver ingredient. Electrochim Acta. 2005;51:956–960. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hipler U.C., Elsner P., Fluhr J.W. Antifungal and antibacterial properties of a silver-loaded cellulosic fiber. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2006;77:156–163. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Changerath R., Nair P.D., Mathew S., Nair C.P. Poly(methyl methacrylate)-grafted chitosan microspheres for controlled release of ampicillin. J Biomed Mater Res B. 2009;89:65–76. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.31188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sen A., Batra A. Evaluation of antimicrobial activity of different solvent extracts of medicinal plant: Melia azedarach L. Int J Curr Pharm Res. 2012;4:67–73. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Potter S.M., Thomas B.D. A new approach to neural cell culture for long-term studies. J Neurosci Methods. 2001;110:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(01)00412-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Méndez J.A., Aguilar M.R., Abraham G.A., et al. New acrylic bone cements conjugated to vitamin E: curing parameters, properties, and biocompatibility. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;62:299–307. doi: 10.1002/jbm.10296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neppel A., Butler I.S. 13C NMR spectra of poly(methyl methacrylate) and poly(ethyl methacrylate) J Mol Struct. 1984;117:109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Horcajada P., Serre C., Vallet-Regí M., Sebban M., Taulelle F., Férey G. Metal-organic frameworks as efficient materials for drug delivery. Angew Chem. 2006;118:6120–6124. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mendes A.N., Hubber I., Siqueira M., et al. Preparation and cytotoxicity of poly(methyl methacrylate) nanoparticles for drug encapsulation. Macromol Symp. 2012;319:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Singh N., Khanna P.K. In situ synthesis of silver nano-particles in polymethylmethacrylate. Mater Chem Phys. 2007;104:367–372. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Emmons E.D., Kraus R.G., Duvvuri S.S., Thompson J.S., Covington A.M. High-pressure infrared absorption spectroscopy of poly(methyl methacrylate) J Polym Sci B: Polym Phys. 2007;45:358–367. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y., Hu W., Lu Z., Li C.M. Photografted poly (methyl methacrylate)-based high performance protein microarray for hepatitis B virus biomarker detection in human serum. Med Chem Commun. 2010;1:132–135. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hasenwinkel J.M., Lautenschlager E.P., Wixson R.L., Gilbert J.L. Effect of initiation chemistry on the fracture toughness, fatigue strength, and residual monomer content of a novel high-viscosity, two-solution acrylic bone cement. J Biomed Mater Res. 2002;59:411–421. doi: 10.1002/jbm.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kong H., Jang J. Antibacterial properties of novel poly(methyl methacrylate) nanofiber containing silver nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2008;24:2051–2056. doi: 10.1021/la703085e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kong H., Jang J. Synthesis and antimicrobial properties of novel silver/polyrhodanine nanofibers. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:2677–2681. doi: 10.1021/bm800574x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.El-Kalla E.H., Sayyah S.M., Afifi H.H., Saeed A.F. Ultraviolet–visible spectroscopic studies of poly(methyl methacrylate) doped with some luminescent materials. Acta Polym. 1989;40:349–351. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Burugapalli K., Thapasimuttu A., Chan J.C., et al. Scaffold with a natural mesh-like architecture: isolation, structural, and in vitro characterization. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:928–936. doi: 10.1021/bm061088x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bumgardner J.D., Wiser R., Gerard P.D., et al. Chitosan: potential use as a bioactive coating for orthopaedic and craniofacial/dental implants. J Biomater Sci Polym Ed. 2003;14:423–438. doi: 10.1163/156856203766652048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aadil K.R., Barapatre A., Meena A.S., Jha H. Hydrogen peroxide sensing and cytotoxicity activity of Acacia lignin stabilized silver nanoparticles. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;82:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.09.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gayathri S., Ghosh O.S.N., Viswanath A.K., Sudhakara P., Reddy M.J.K., Shanmugharaj A.M. Synthesis of YF3: Yb, Er upconverting nanofluorophores using chitosan and their cytotoxicity in MCF-7 cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;72:1308–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Younes I., Frachet V., Rinaudo M., Jellouli K., Nasri M. Cytotoxicity of chitosans with different acetylation degrees and molecular weights on bladder carcinoma cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2016;84:200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Patil H.G., Gundavda M., Shetty V., Soman R., Rodriques C., Agashe V.M. Musculoskeletal melioidosis: an under-diagnosed entity in developing countries. J Orthop. 2016;13:40–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2015.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Karaduman M., Okkaoglu M.C., Sesen H., Taskesen A., Ozdemir M., Altay M. Platelet-rich plasma versus open surgical release in chronic tennis elbow: a retrospective comparative study. J Orthop. 2016;13:10–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muñoz-Egea M.C., Blanco A., Fernández-Roblas R., et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of patients with septic arthritis: a hospital-based study. J Orthop. 2014;11:87–90. doi: 10.1016/j.jor.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.