Abstract

Cells are dynamic systems that generate and respond to forces over a range of spatial and temporal scales, spanning from single molecules to tissues. Substantial progress has been made in recent years in identifying the molecules and pathways responsible for sensing and transducing mechanical signals to short-term cellular responses and longer-term changes in gene expression, cell identity, and tissue development. In this perspective article, we focus on myosin motors, as they not only function as the primary force generators in well-studied mechanobiological processes, but also act as key mechanosensors in diverse functions including intracellular transport, signaling, cell migration, muscle contraction, and sensory perception. We discuss how the biochemical and mechanical properties of different myosin isoforms are tuned to fulfill these roles in an array of cellular processes, and we highlight the underappreciated diversity of mechanosensing properties within the myosin superfamily. In particular, we use modeling and simulations to make predictions regarding how diversity in force sensing affects the lifetime of the actomyosin bond, the myosin power output, and the ability of myosin to respond to a perturbation in force for several nonprocessive myosin isoforms.

Main Text

Exciting experiments in the field of mechanobiology have demonstrated that molecules, cells, and tissues are able to sense their environments and respond biologically to mechanical signals (1). Mechanical force is sensed by load-induced changes in the conformation and/or activities of mechanosensitive macromolecules (i.e., mechanosensors), which in turn lead to a biological response. In mechanosensitive molecules such as p130Cas (2), von Willebrand factor (3), and titin (4), mechanical stress causes local protein unfolding that leads to the exposure of cryptic binding sites and/or sites of posttranslational modifications. In other proteins, such as Dam1 (5) and PSGL1 (6), force affects the interaction between a protein and its binding partner allosterically rather than through the exposure of cryptic sites. This allosteric tuning can either accelerate or slow the rate of bond dissociation. Forces can also directly alter enzymatic activities of mechanosensitive proteins such as myosin (below) or the opening probabilities of mechanosensitive ion channels (reviewed in (7)).

The kinetics of the interaction between the molecular motor myosin and its cytoskeletal track, actin, can be allosterically tuned by force; however, in contrast to many other mechanosensitive proteins where the forces acting on the proteins are externally imposed, the forces affecting myosin can be externally imposed or internally generated by the myosin itself working against substrates of varied stiffnesses. It can be argued that skeletal muscle myosin, the motor that powers our locomotion, was one of the first recognized mechanosensors. In landmark experiments conducted in the 1920s, W. O. Fenn showed that a muscle contracting against a resisting load generates less heat (i.e., uses less ATP) than a muscle shortening in the absence of a load (8). These experiments were complemented by the work of A. V. Hill, which showed that the velocity of muscle shortening decreases nonlinearly with increasing force (9). Based on these observations, Hill proposed that force slows the enzymatic and motile activities of muscle myosin. In other words, besides acting as a force generator, muscle myosin also functions as a mechanosensor that changes its rate of motility in response to force. Subsequently, it has been shown that a muscle’s force sensitivity and rate of force development depend on its fiber type (10, 11), suggesting that different myosin isoforms confer distinct mechanosensing properties to the muscle. We now know that the myosin gene family is large, and that the different isoforms have a range of force-generating properties that have evolved to function in a large array of physiological functions that extend beyond powering muscle contraction.

Since the publication of these classic muscle physiology studies, single-molecule experiments have directly demonstrated that slowing of motility by force can be explained in part by changes in the attachment and detachment kinetics of actin-bound myosin (actomyosin). Depending on the magnitude of forces on myosin, actomyosin interactions can be described as catch- or slip-bonds, which have lifetimes that increase or decrease, respectively, with load. Notably, there are several features of the force dependence of the actomyosin interaction that distinguish its behavior from other catch- and slip-bonds, because these behaviors in myosin depend on its enzymatic activity. Moreover, different myosin isoforms can show distinct mechanosensing behaviors at a given force.

Mechanosensing by myosin is regulated by chemical and mechanical forces

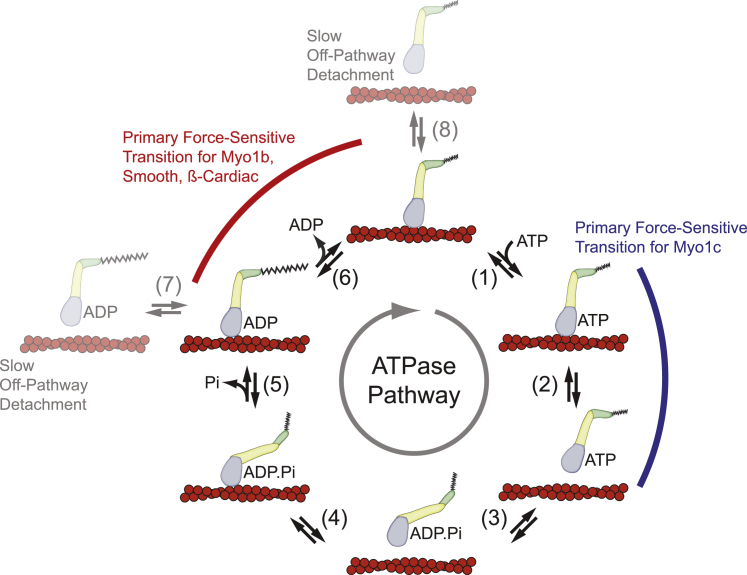

To understand mechanosensing by myosin, knowledge of its mechanochemical pathway is required. All characterized myosins hydrolyze ATP via the same biochemical pathway and likely share similar mechanical intermediates (Fig. 1). Myosin detaches from actin upon ATP binding (Fig. 1, steps 1 and 2), myosin isomerizes to the prepowerstroke conformation, and ATP is hydrolyzed while myosin holds ADP and inorganic phosphate noncovalently in its active site (Fig. 1, step 3). Rebinding of myosin to actin induces the release of phosphate and the force-generating powerstroke (Fig. 1, steps 4 and 5), and ADP is released to complete the cycle (Fig. 1, step 6). The duty ratio, i.e., the fraction of time myosin spends attached to actin in its biochemical cycle, correlates with the ability of myosin ensembles to generate force. It is crucial for the reader to note that 1) in many cases, the motility rate is limited by the detachment rate of myosin from actin (12); 2) the magnitude of force generated by an ensemble of myosins is proportional to the number of myosins bound strongly to actin; and 3) there are orders-of-magnitude variations among myosin isoforms in the rates and equilibrium constants that define their biochemical pathways, resulting in incredible diversity of sliding rates and force production (13).

Figure 1.

The myosin mechanochemical cycle. Although all characterized myosins follow this cycle, the individual rate and equilibrium constants can vary by several orders of magnitude for different myosin isoforms. Force can also affect the rates and equilibrium constants of the various transitions in an isoform-specific manner, leading to diversity of mechanosensing behaviors. Force can also promote actomyosin detachment through off-ATPase-pathway transitions (steps 7 and 8). To see this figure in color, go online.

Critically, the rates and equilibrium constants of the biochemical and mechanical transitions shown in Fig. 1 can be modulated by force. To a first-order approximation, the effects of force on a kinetic rate (e.g., the rate of bond dissociation or ADP release) can be described by the Bell equation, which assumes an Arrhenius transition model (14):

| (1) |

where kf0 is the rate in the absence of force, F is the force on the molecule (where a positive F is a force that resists motion), kB is Boltzmann’s constant, T is the temperature, and d is the distance to the force-dependent transition state, also known as the distance parameter. Note, k(F) changes exponentially with d, which is a vector quantity that depends on the direction of the applied force. In this article, a positive d indicates a force that resists the forward motion of the myosin working stroke in the direction of the long-axis of the actin filament. At sufficiently high loads, all bonds become slip bonds, a behavior that is not captured in Eq. 1. It is important to note that the magnitude of d does not have to correspond to the size of the working stroke (15), and although d is proportional to the length of the lever arm in some myosin isoforms (16, 17), the exact structural elements responsible for myosin mechanosensing are still not resolved.

The effect of force on the actomyosin attachment lifetime depends on the magnitude of the force and whether the myosin is catalytically activated. In the case of rigor or ADP-bound skeletal muscle myosin (i.e., in the absence of ATP when the myosin is not enzymatically cycling), the actomyosin states from which myosin detaches directly from actin (Fig. 1, steps 7 and 8) can be described as catch bonds at forces <5 pN and as slip bonds at forces >10 pN (18). Although noncycling actomyosin-V bound to ADP behaves as a catch bond, where force slows the rate of actomyosin-V dissociation, similar forces on ADP-bound actomyosin-VI cause the actomyosin bond to behave as a slip bond (19). However, it is important to note that these states dissociate very slowly from actin in the absence of force so that detachment from these states rarely occurs during active ATP cycling at physiological ATP concentrations. Rather, the pathway for dissociation that dominates under physiological conditions in cycling myosins is ATP-induced dissociation after ADP release (Fig. 1, step 2). In an active myosin, mechanical forces can theoretically affect any of the transitions among the actin-bound intermediates on the ATPase pathway. Moreover, the exact transition that limits turnover and is affected by force appears to be isoform specific, ranging from reversing the powerstroke to slowing the rates of ATP binding, ADP release, and/or an isomerization associated with ADP release (see below). Because these rates determine the attachment duration, sliding velocity, and power output, it is critical to consider exactly which transitions are affected by mechanical force. Force can affect the kinetic flux through different dissociation pathways (e.g., ATP-induced actomyosin dissociation, nucleotide-free actomyosin dissociation, and ADP-bound actomyosin dissociation), not just the probability of rupture of the actomyosin bond. As such, a simple two-state model, which is sometimes used to describe bond dissociation in the absence of enzymatic cycling, will often fail to capture the true behavior of the actomyosin interaction.

Diversity of myosin mechanosensors

There are 38 different myosin genes expressed in humans (20, 21), and although many of these have been characterized biochemically, only a few have been studied mechanically. Here, we introduce to the reader four examples of nonprocessive myosins that demonstrate substantial diversity in biochemical and mechanosensing properties.

Myosin-Ib (gene: MYO1B)

Myosin-Ib (Myo1b) is a single-headed, low-duty-ratio motor (in the absence of force) from the myosin-I family (22) that has been proposed to have roles in powering changes in Golgi morphology, endosomal movements, and signaling at the plasma membrane (23). Its motility rate is slow (120 nm/s at 37°C) and limited by the rate of ADP release (7 s−1 at 37°C and 2.1 s−1 at 20°C (17); Fig. 1, step 6). Single-molecule optical trapping experiments have shown that mechanical forces that resist the Myo1b powerstroke dramatically slow the rate of ADP release, which in turn slows the rate of motility (Fig. 1, step 6). Although ADP remains trapped in the active site for an extended period of time in the presence of force, at forces <2 pN, it is eventually released, allowing rapid ATP binding and subsequent actomyosin dissociation (Fig. 1, step 2). Modeling the force dependence of ADP release (Eq. 1) yields a distance parameter (d = 18 nm) that is far larger than measured for any other characterized nonprocessive myosin (24). The actomyo1b detachment rate slows by nearly two orders of magnitude at forces <2 pN compared to the unloaded rate, increasing the average actin-attachment lifetime from <0.5 s to ∼50 s. This catch-bond-like behavior of the actomyo1b interaction enables Myo1b to act as a tension-sensitive anchor, suitable for playing a role in extending and holding membrane extensions. At forces >2 pN, the detachment rate becomes force independent, because the rate of ADP release from actomyosin becomes slower than the rate at which myosin-ADP dissociates directly from actin (Fig. 1, step 7) without proceeding through the canonical ATPase pathway.

Myosin-Ic (gene: MYO1C)

Myosin-Ic (Myo1c) is a member of the myosin-I family that participates in recycling of lipid-raft cargos, exocytosis, and sensory transduction. It has unloaded kinetic rate constants similar to those of Myo1b (25, 26, 27), with a low duty ratio in the absence of force (28) and slow motility (75 nm/s at 37°C (28)) that is limited by the rate of ADP release in the absence of force (24 s−1 at 37°C (28) and 3.9 s−1 at 20°C (25)). Despite the similarities in the Myo1b and Myo1c unloaded kinetics and sequences, their behaviors under loaded conditions differ considerably. Unlike actomyo1b, the actomyo1c detachment rate is largely insensitive to forces <1 pN that resist its powerstroke, so it does not have a catch-bond-like behavior (25). At forces >1 pN, the rate of actomyo1c dissociation slows with force (d = 5.2 nm), albeit more modestly than that of actomyo1b. Therefore, the actomyo1c interaction displays catch-bond-like behavior only at higher forces. This behavior is modeled by considering the effects of force on two biochemical transitions. The rate of ADP release (Fig. 1, step 6), which limits actin detachment and motility in the absence of force, is less force sensitive than the rate of ATP-induced dissociation (Fig. 1, step 2). The rate of ATP-induced dissociation is faster than the rate of ADP release at low forces, but forces >1 pN slow this step to the point where it limits the rate of actomyosin dissociation (25). The functional effect of these differences is dramatic. Although 1 pN of force will stall a single Myo1b molecule, the same force will have little effect on the motile rate of Myo1c, which will continue to generate power. This behavior of Myo1c may facilitate the motor’s ability to drive vesicle motility against resisting loads or to respond rapidly to changes in force when working as an ensemble (see below).

Smooth muscle myosin-II (gene: MYH11)

The MYH11 gene codes for the myosin-II motor that powers the contraction of smooth muscles, which are found in the vasculature, gastrointestinal tract, urinary bladder, and other organs. In the absence of force, smooth muscle myosin-II is a low-duty-ratio motor (29). When placed under loads that resist the powerstroke, the rate of ADP release, or an isomerization associated with ADP release (Fig. 1, step 6 (30)) slows, resulting in an increase in the actomyosin attachment lifetime and slower motility rate. The force-dependent actin-detachment rate is well described by Eq. 1, with a distance parameter of 2.7 nm, such that a load of 1 pN decreases the rate of actin detachment from 24 s−1 to 12 s−1 (31). Moreover, forces that assist the powerstroke accelerate the rate of actomyosin dissociation. A recent report suggests that the unloaded motility rate of smooth muscle myosin filaments may be limited by actin-attachment kinetics, so it is interesting to speculate that force may also affect the sliding velocity by changing both actin-attachment and actin-detachment kinetics (32).

β-Cardiac muscle myosin-II (gene: MYH7)

β-cardiac muscle myosin-II, the primary force-generating myosin in human heart ventricles, generates power to pump blood to the body’s extremities. In the absence of force, it has a low duty ratio (33) and a fast motility rate (800 nm/s at 23°C (34)) that is limited by the rate of ADP release (65 s−1 at 15°C (35)). Forces that resist the powerstroke slow the rate of ADP release at physiological ATP concentrations. The distance to the transition state for actomyosin dissociation is 0.97 nm (36, 37), such that 1 pN of load slows the rate of actin detachment from 83 s−1 to 66 s−1. This force sensitivity is more modest than Myo1b, Myo1c, or smooth muscle myosin-II, which is likely important for cardiac myosin's role in generating sufficient power to counteract cardiac afterload. It is worth noting that in skeletal muscle myosin-II, rapidly applied loads that oppose the powerstroke can increase the rate of the reversal of the myosin powerstroke (Fig. 1, step 5), inducing dissociation after the initial attachment event (38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43). Additionally, exciting new work has suggested a role for mechanical activation of the myosin thick filament in skeletal muscle that may be independent of the mechanochemistry of the motor (44). It is possible that cardiac muscle myosin-II also has similar force-sensing behaviors.

Different force-sensing properties of individual motors lead to diverse physiology

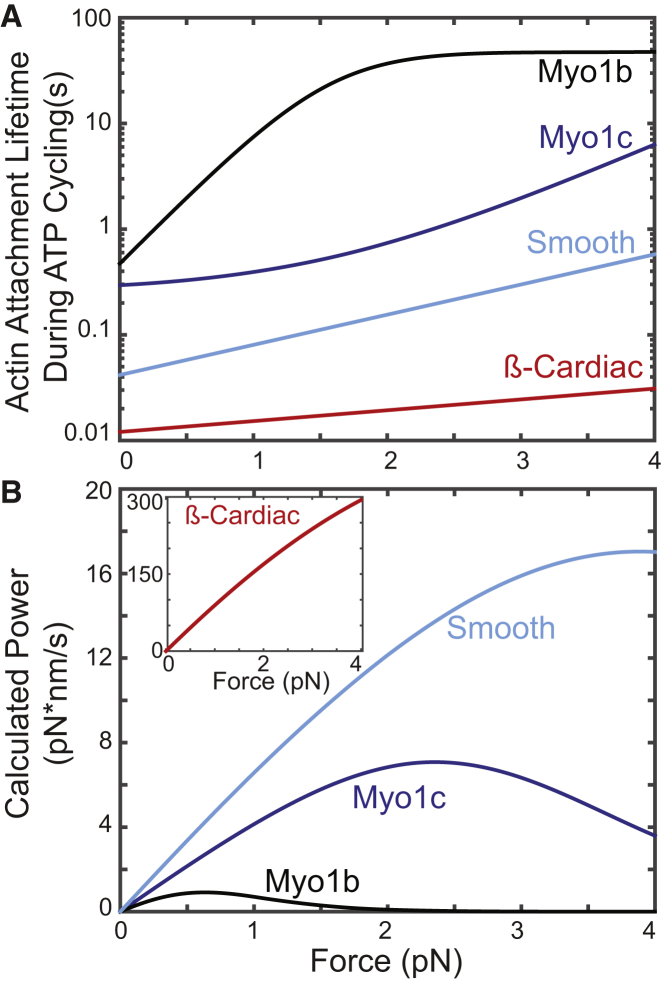

Plots of calculated actomyosin attachment lifetimes versus force for the isoforms listed above demonstrate the remarkable mechanochemical diversity of these motors (Fig. 2). The physiological range of forces experienced by these myosins is not known, so we plot the range of forces experimentally detected in single-molecule optical trapping experiments (17, 24). The attachment durations of the various myosin isoforms in the absence of force vary by almost two orders of magnitude. The application of forces affects the attachment durations for each of these isoforms differently. Simple calculations of power output (i.e., the amount of work the myosin can perform as a function of time assuming detachment-limited kinetics) shows that Myo1b has a low power output over a narrow range of forces, and although Myo1c can generate force and power over a broader range of loads, its peak power output is dramatically lower than the those of the myosin-II isoforms. Comparing the two muscle isoforms, it is apparent that β-cardiac myosin can produce greater power over a broader range of forces than smooth muscle myosin-II, consistent with its role in driving cardiac muscle contraction.

Figure 2.

(A) The calculated actomyosin attachment duration as a function of force resisting the powerstroke. The unloaded attachment durations vary by several orders of magnitude between the various myosin isoforms. Moreover, the effect of force on the myosin attachment duration is isoform specific. Whereas 1 pN of force increases the attachment duration of actomyo1b by two orders of magnitude, it has almost no effect on the attachment lifetime of actomyo1c and a small effect on β-cardiac and smooth muscle myosins. (B) The calculated power output of various myosin isoforms as a function of force. Power was calculated as described previously (25). Myo1b has a very low power output over a narrow range of forces, consistent with the expected properties of a tension-sensing anchor. The closely related myosin-I isoform, Myo1c, has a higher power output over a larger range of forces, consistent with the expected properties of a slow transporter. β-Cardiac and smooth muscle myosin-II have larger power outputs, consistent with their roles in powering muscle contraction; however, the power output of β-cardiac myosin-II (inset) is much greater than the power output of smooth muscle myosin-II, reinforcing the concept that there can be large diversity of mechanosensing within a myosin family. It is important to note that these power outputs are calculated assuming that all of the myosins work in similar sized ensembles, and that the calculations do not take into account interactions between motors. To see this figure in color, go online.

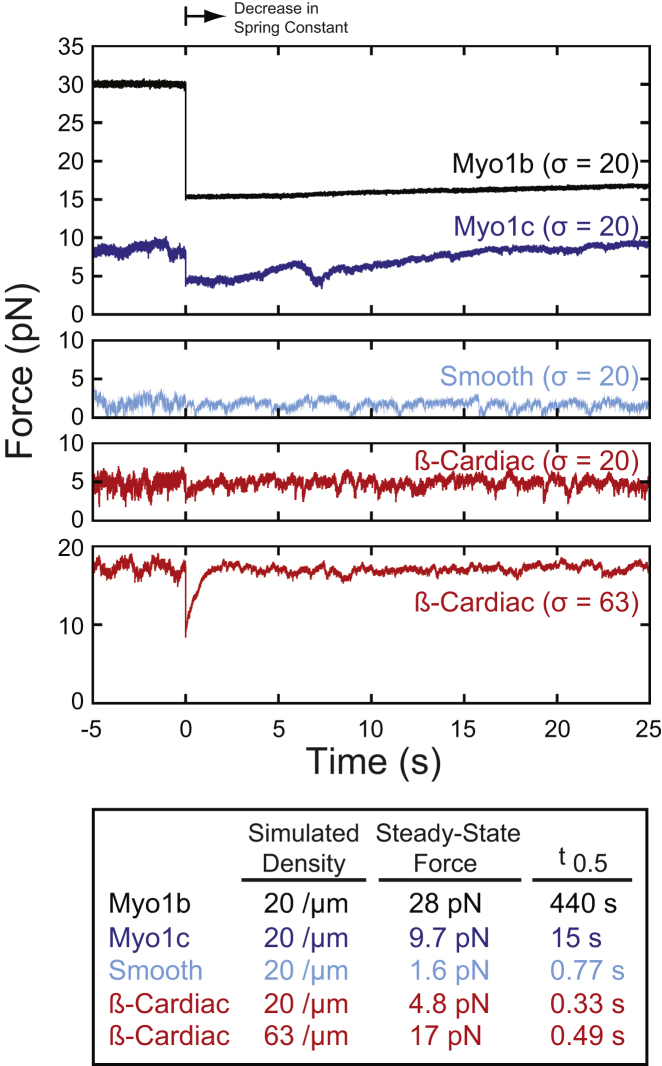

Two additional parameters relevant to myosin mechanosensing are the force generated by myosin ensembles and the ability of the ensemble to respond to a perturbation in force. To predict how force-dependent properties of myosin may affect the ability of an ensemble of myosins to generate force and to respond to force perturbations, we conducted simulations of force generation by myosins bound to a surface acting against a spring with a stiffness of 0.2 pN/nm, followed by a rapid decrease in stiffness to 0.1 pN/nm (Fig. 3; see the Supporting Material). Simulations suggest that the steady-state forces produced by the myosin ensembles differ (Fig. 3), which can be explained by differences in their force-dependent duty ratios. This is clearly seen in the higher forces developed by Myo1b compared to Myo1c, despite their similar unloaded kinetics and steady-state force per motor (Figs. 3 and S2). Moreover, simulations predict that the forces developed by β-cardiac and smooth myosins at an equivalent motor density are lower, because force causes only a modest increase in the fraction of force generating actomyosin interactions bound to actin. Higher concentrations of motors are able to produce larger forces, as illustrated in the simulation of β-cardiac myosin at a density of motors similar to that found in a sarcomere (Fig. 3). The reader is reminded not to confuse force with power, as myosin-II isoforms continue to perform substantial work under load. Importantly, the simulations reveal possible differences in the time it takes myosin to respond to changes in force. If the myosin is subjected to a change in force (in this case by reducing the stiffness of the spring the myosins are working against by twofold), the amount of time necessary to respond (i.e., the time for the force to recover to isometric tension) will depend on force-dependent ATPase kinetics and force-velocity relationships (Fig. 3). Readers are encouraged to view a supplemental movie of the simulations (Movie S1), since one can visually appreciate the differences in the actin attachment and detachment dynamics of the different myosin isoforms.

Figure 3.

Simulations of nonprocessive myosins working against a load with a spring constant of 0.2 pN/nm were conducted as described in the Supporting Material. At steady state, the myosin generates its isometric force. At t = 0, the spring constant was reduced twofold, and the time constant for the force to return to the isometric level for this trace is reported in the table. The four myosin isoforms have dramatically different isometric forces and response times. Notably, Myo1b and Myo1c both have similar unloaded kinetics but different isometric tensions and rates at which they respond to perturbations in force. The forces developed by smooth muscle myosin-II and β-cardiac myosin are small due to their low duty ratios and force-sensitive kinetics. When the density of β-cardiac myosin was increased approximately to that found in a muscle sarcomere (bottom), the isometric force increased, allowing the rapid force recovery to be seen. Movies illustrating the simulations can be found in the Supporting Material. Values of the steady-state forces and t0.5 values obtained from the average of 10 traces are available in Table S4. To see this figure in color, go online.

Nonmuscle myosin-II in cellular mechanosensing

The actin cytoskeleton is coupled to the extracellular matrix and adjacent cells via focal adhesions and adherens junctions, respectively. Mechanical signals from the internal and external environments are sensed and integrated at these sites, leading to changes in cellular signaling. Many proteins found at these sites have been identified as mechanosensitive, including the β-catenin-αE-cadherin complex in adherens junctions that increases its actin affinity in the presence of force (45). In focal adhesions, stretching of the integrin-binding protein talin causes the exposure of cryptic binding sites for both vinculin and integrins, leading to a strengthening of the adhesions (46, 47). Similarly, forces on filamin A weaken its association with the Rac-GTPase FilGAP, initiating downstream signaling cascades that deactivate Rac signaling while at the same time exposing a binding site where β7-integrin can bind (48). The downstream effects of this signaling are of great consequence. For example, it has been shown that stem cells can sense the stiffness of the surface on which they are grown through focal adhesions, which leads to differentiation into various cell lineages (49).

Nonmuscle myosin-II (NMII) activity has been proposed to play a pivotal role in mechanosensing in both adherens junctions and focal adhesions, where it is widely accepted that it generates forces that are sensed by other mechanosensitive proteins in these structures. NMII activity is essential for focal-adhesion maturation, where it is coupled to the actin that is bound to focal adhesions (50, 51). In these adhesions, NMII isoforms work against the traction force provided by the focal adhesions, allowing for cell adhesion, cell migration, and sensing of the matrix stiffness. In adherens junctions, it has been proposed that NMII generates forces on actin that lead to the stable assembly of the β-catenin-αE-cadherin complex (52).

Although the role of NMII in generating forces at these structures is widely appreciated, its role as a mechanosensor is not, although recent models (53) and experimental work in lower organisms (54, 55, 56) have nicely accounted for myosin mechanosensitivity. The magnitude of force, the rate at which force develops, and the rate at which the cell is able to respond to changes in force and stiffness will depend on the kinetic and force-dependent properties of the myosin isoforms. From our knowledge of the myosin family, it is expected that NMII dynamically adjusts its power output as a function of load on these adhesive structures. As the load changes, sliding velocities, ensemble force production, and actin detachment rates are expected to change in an isoform-dependent manner. Thus, as recent modeling has shown (53), it is important to consider the role of myosins beyond that of simple force generators or generic catch bonds.

There are three NMII isoforms (NMIIA from the MYH9 gene, NMIIB from the MYH10 gene, and NMIIC from the MYH14 gene) expressed in vertebrates with distinct biochemical properties. These isoforms are activated and form filaments when their regulatory light chains are phosphorylated (except for one NMIIC splice isoform (57)), enabling the production of force. NMIIA is enriched at the leading edge of migrating cells, whereas NMIIB is more localized at the center and rear of migrating cells (58). It is important to note that each of these myosin isoforms can form heteropolymers with the other NMII isoforms. The activities of both NMIIA and NMIIB have been suggested to be important for the formation and maturation of focal adhesions (50, 51). Each of these myosins has different motile rates and duty ratios (59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65). Single NMIIA and NMIIB motors have been suggested to have a high-duty-ratio motor than can move processively along actin, but this assertion remains controversial (59, 60, 61, 63, 65, 66). Transient kinetic experiments suggest that NMIIA and NMIIB both show force-dependent changes in the rate of ADP release, where forces that resist the powerstroke slow the rate of ADP release, prolonging the attachment duration of actomyosin (65), but optical trapping experiments have shown conflicting results (59, 60, 66).

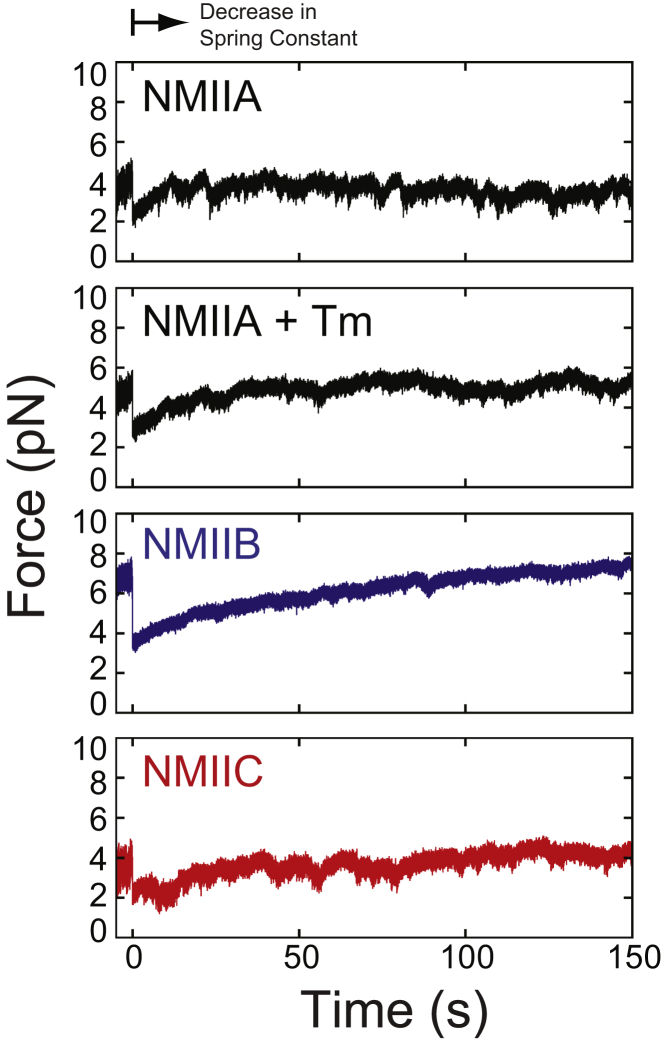

To probe possible mechanosensing properties of these motors, we simulated the force-dependent behavior of NMII isoforms using their measured ATPase kinetic properties (Fig. 4). The mechanical properties of NMIIC have not been measured. We assumed that NMIIC has a working-stroke displacement of 6 nm, similar to NMIIA (66), NMIIB (60), and other myosin-II isoforms (31, 36, 66, 67, 68). We assumed that force slows the rate of ADP release and sliding velocity with a distance to the transition state of 3 nm in this isoform, similar to NMIIA (66), NMIIB (59), and smooth muscle myosin-II (31). It is important to note that small differences in the distance parameter can lead to vastly different responses under load, and that this myosin may have an alternative biochemical transition that is tuned by force, since even closely related myosins can have distinct force-sensing properties (Figs. 2 and 3). Moreover, a recent report on NMIIA showed that these force-sensing properties can also be modulated by tropomyosin, suggesting additional modes of regulation (66). Therefore, we also simulated NMIIA in the presence of tropomyosin (NMIIA+Tm). We assumed that tropomyosin did not change the kinetics of the myosin; however, if it does (66), its effect could be even more profound. To allow comparison between these myosins, we assumed that the myosins formed filaments with 30 heads, similar to filaments of NMIIA and NMIIB (69); however, the number of heads in vivo could be quite different, especially for NMIIC. Given those assumptions, simulations suggest that NMII isoforms have up to twofold differences in steady-state forces and up to ∼10-fold differences in the rates at which they can respond to changes in force (Table S5). Kinetic differences are also apparent in Movie S2. These simulated forces and response rates for nonmuscle myosin-IIs are different from those of β-cardiac and smooth muscle myosin-II isoforms. Thus, care should be used when building models of adherens junctions and focal adhesions without accounting for the different mechanochemical properties of these myosins. The idea that these myosins act as simple catch bonds is likely an oversimplification, and it may not describe the entire role of myosins in these processes (53). This point is strengthened by recent studies showing that these myosins can copolymerize both with each other and with myosin 18A (70) and that there may be diversity in the number of myosins in a filament (69). As such, the mechanosensing properties of these myosin filaments in vivo are likely quite complex.

Figure 4.

Simulations of nonmuscle myosin-II isoforms working against a load with a spring constant of 0.2 pN/nm were conducted as described in the Supporting Material. The myosins were allowed to generate isometric tension before the spring constant was reduced by twofold. The various myosin-II isoforms have distinct steady-state force productions and response times to perturbations in force. Values of the steady-state forces and t0.5 values obtained from the average of 10 traces are available in Table S5. To see this figure in color, go online.

Conclusions

Myosins have an important role as mechanosensors in a wide variety of cellular processes, where they are mechanically and kinetically tuned to their specific molecular roles in the cell. This tuning must account for the fact that the motor generating the force must also respond to force. The range of mechanosensing behaviors seen in myosins is quite diverse and it is often more complicated than a conventional catch bond due to the fact that the actomyosin lifetime depends on the enzymatic activity of the myosin.

Despite their roles in many cellular processes, only a handful of myosin motors have been characterized mechanically. As demonstrated here, the molecular role of a myosin in the cell is intrinsically interwoven with its mechanosensing properties. As such, mechanical experiments are required to determine the molecular roles of these myosins in their various cellular processes. It will be interesting to see how other myosin isoforms are involved in mechanosensing and mechanotransduction in the cell.

Author Contributions

M.J.G., E.T., and E.M.O. wrote the manuscript. G.A. and E.T. performed the modeling.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01GM057247 to E.M.O., R00HL123623 to M.J.G., and R01GM100076 to E.T.).

Editor: Brian Salzberg.

Footnotes

Supporting Materials and Methods, two figures, five tables, and two movies are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30303-4.

Supporting Citations

References (71, 72) appear in the Supporting Material

Supporting Material

Sample movie from simulations showing the time-dependent position of an actin filament over a pedestal containing Myo1b, Myo1c, smooth muscle, and β-cardiac muscle myosin-II motors (σ = 20 motors/μm). The trap force is shown by springs connected to the filament ends. Motors are color-coded to show the force exerted at a given time. The look-up table for the color-coding was selected to give a dynamic range around forces of ∼1 pN. Fcutoff is the mean force plus one standard deviation that is exerted by actin-bound myosins at a given frame, averaged over all the frames. This cutoff force is 1.8 pN, 1.9 pN, 1.7 pN, and 1.7 pN for Myo1b, Myo1c, smooth muscle, and β-cardiac muscle myosin-II, respectively. Motors with forces that exceed the cut-off value are shown in green. The plots below the movie show the number of motors bound to the actin (N), the position of the actin filament, and the trap force (F), respectively. The spring constant is decreased twofold at t = 0 s.

Sample movie from simulations showing the time-dependent position of an actin filament over a pedestal containing NMIIA, NMIIB, and NMIIC motors (σ = 20 motors/μm). The trap force is shown by springs connected to the filament ends. Motors are color-coded to show the force exerted at a given time. Fcutoff is the mean force plus one standard deviation that is exerted by actin-bound myosins at a given frame, averaged over all the frames. This cutoff force is 1.4 pN, 1.4 pN, 1.3 pN and 1.6 pN for NMIIA, NMIIA+Tm, NMIIB, and NMIIC motors, respectively. Motors with forces that exceed the cut-off value are shown in green. The plots below the movie show the number of motors bound to the filament (N), the position of the actin filament, and the trap force (F), respectively. The spring constant is decreased twofold at t = 0 s. The movie is from simulations performed using the same parameters as in Fig. 4, but with different traces.

References

- 1.Jansen K.A., Donato D.M., Koenderink G.H. A guide to mechanobiology: where biology and physics meet. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1853(11 Pt B):3043–3052. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sawada Y., Tamada M., Sheetz M.P. Force sensing by mechanical extension of the Src family kinase substrate p130Cas. Cell. 2006;127:1015–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X., Halvorsen K., Springer T.A. Mechanoenzymatic cleavage of the ultralarge vascular protein von Willebrand factor. Science. 2009;324:1330–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.1170905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hidalgo C., Granzier H. Tuning the molecular giant titin through phosphorylation: role in health and disease. Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 2013;23:165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volkov V.A., Zaytsev A.V., Grishchuk E.L. Long tethers provide high-force coupling of the Dam1 ring to shortening microtubules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:7708–7713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305821110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshall B.T., Long M., Zhu C. Direct observation of catch bonds involving cell-adhesion molecules. Nature. 2003;423:190–193. doi: 10.1038/nature01605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gu Y., Gu C. Physiological and pathological functions of mechanosensitive ion channels. Mol. Neurobiol. 2014;50:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s12035-014-8654-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fenn W.O. A quantitative comparison between the energy liberated and the work performed by the isolated sartorius muscle of the frog. J. Physiol. 1923;58:175–203. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1923.sp002115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hill A.V. The heat of shortening and the dynamic constants of muscle. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 1938;126:136–195. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1949.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Larsson L., Moss R.L. Maximum velocity of shortening in relation to myosin isoform composition in single fibres from human skeletal muscles. J. Physiol. 1993;472:595–614. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Close R.I. Dynamic properties of mammalian skeletal muscles. Physiol. Rev. 1972;52:129–197. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1972.52.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huxley H.E. Sliding filaments and molecular motile systems. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:8347–8350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman Y.E., Ostap E.M. Myosin motors: kinetics of myosin. In: Goldman Y.E., Ostap E.M., editors. Comprehensive Biophysics: Molecular Motors and Motility. Elsevier; Amsterdam, the Netherlands: 2011. pp. 151–169. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bell G.I. Models for the specific adhesion of cells to cells. Science. 1978;200:618–627. doi: 10.1126/science.347575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsygankov D., Fisher M.E. Mechanoenzymes under superstall and large assisting loads reveal structural features. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:19321–19326. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709911104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laakso J.M., Lewis J.H., Ostap E.M. Control of myosin-I force sensing by alternative splicing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:698–702. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911426107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lewis J.H., Greenberg M.J., Ostap E.M. Calcium regulation of myosin-I tension sensing. Biophys. J. 2012;102:2799–2807. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guo B., Guilford W.H. Mechanics of actomyosin bonds in different nucleotide states are tuned to muscle contraction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9844–9849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601255103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oguchi Y., Mikhailenko S.V., Ishiwata S. Load-dependent ADP binding to myosins V and VI: implications for subunit coordination and function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:7714–7719. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800564105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray K.A., Yates B., Bruford E.A. Genenames.org: the HGNC resources in 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D1079–D1085. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berg J.S., Powell B.C., Cheney R.E. A millennial myosin census. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2001;12:780–794. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.4.780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis J.H., Lin T., Ostap E.M. Temperature dependence of nucleotide association and kinetic characterization of myo1b. Biochemistry. 2006;45:11589–11597. doi: 10.1021/bi0611917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Greenberg M.J., Ostap E.M. Regulation and control of myosin-I by the motor and light chain-binding domains. Trends Cell Biol. 2013;23:81–89. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laakso J.M., Lewis J.H., Ostap E.M. Myosin I can act as a molecular force sensor. Science. 2008;321:133–136. doi: 10.1126/science.1159419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenberg M.J., Lin T., Ostap E.M. Myosin IC generates power over a range of loads via a new tension-sensing mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:E2433–E2440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207811109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adamek N., Coluccio L.M., Geeves M.A. Calcium sensitivity of the cross-bridge cycle of Myo1c, the adaptation motor in the inner ear. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:5710–5715. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710520105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Batters C., Arthur C.P., Coluccio L.M. Myo1c is designed for the adaptation response in the inner ear. EMBO J. 2004;23:1433–1440. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin T., Greenberg M.J., Ostap E.M. A hearing loss-associated myo1c mutation (R156W) decreases the myosin duty ratio and force sensitivity. Biochemistry. 2011;50:1831–1838. doi: 10.1021/bi1016777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harris D.E., Warshaw D.M. Smooth and skeletal muscle myosin both exhibit low duty cycles at zero load in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:14764–14768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nyitrai M., Geeves M.A. Adenosine diphosphate and strain sensitivity in myosin motors. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004;359:1867–1877. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Veigel C., Molloy J.E., Kendrick-Jones J. Load-dependent kinetics of force production by smooth muscle myosin measured with optical tweezers. Nat. Cell Biol. 2003;5:980–986. doi: 10.1038/ncb1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brizendine R.K., Alcala D.B., Cremo C.R. Velocities of unloaded muscle filaments are not limited by drag forces imposed by myosin cross-bridges. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:11235–11240. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510241112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deacon J.C., Bloemink M.J., Leinwand L.A. Identification of functional differences between recombinant human α and β cardiac myosin motors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2012;69:2261–2277. doi: 10.1007/s00018-012-0927-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sommese R.F., Sung J., Spudich J.A. Molecular consequences of the R453C hypertrophic cardiomyopathy mutation on human β-cardiac myosin motor function. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:12607–12612. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309493110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siemankowski R.F., Wiseman M.O., White H.D. ADP dissociation from actomyosin subfragment 1 is sufficiently slow to limit the unloaded shortening velocity in vertebrate muscle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1985;82:658–662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.3.658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Greenberg M.J., Shuman H., Ostap E.M. Inherent force-dependent properties of β-cardiac myosin contribute to the force-velocity relationship of cardiac muscle. Biophys. J. 2014;107:L41–L44. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sung J., Nag S., Spudich J.A. Harmonic force spectroscopy measures load-dependent kinetics of individual human β-cardiac myosin molecules. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7931. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Caremani M., Dantzig J., Linari M. Effect of inorganic phosphate on the force and number of myosin cross-bridges during the isometric contraction of permeabilized muscle fibers from rabbit psoas. Biophys. J. 2008;95:5798–5808. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.130435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linari M., Caremani M., Lombardi V. A kinetic model that explains the effect of inorganic phosphate on the mechanics and energetics of isometric contraction of fast skeletal muscle. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2010;277:19–27. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2009.1498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takagi Y., Homsher E.E., Shuman H. Force generation in single conventional actomyosin complexes under high dynamic load. Biophys. J. 2006;90:1295–1307. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.068429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takagi Y., Shuman H., Goldman Y.E. Coupling between phosphate release and force generation in muscle actomyosin. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2004;359:1913–1920. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dantzig J.A., Goldman Y.E., Homsher E. Reversal of the cross-bridge force-generating transition by photogeneration of phosphate in rabbit psoas muscle fibres. J. Physiol. 1992;451:247–278. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1992.sp019163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith D.A., Geeves M.A. Strain-dependent cross-bridge cycle for muscle. Biophys. J. 1995;69:524–537. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)79926-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linari M., Brunello E., Irving M. Force generation by skeletal muscle is controlled by mechanosensing in myosin filaments. Nature. 2015;528:276–279. doi: 10.1038/nature15727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buckley C.D., Tan J., Dunn A.R. Cell adhesion. The minimal cadherin-catenin complex binds to actin filaments under force. Science. 2014;346:1254211. doi: 10.1126/science.1254211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.del Rio A., Perez-Jimenez R., Sheetz M.P. Stretching single talin rod molecules activates vinculin binding. Science. 2009;323:638–641. doi: 10.1126/science.1162912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ciobanasu C., Faivre B., Le Clainche C. Actomyosin-dependent formation of the mechanosensitive talin-vinculin complex reinforces actin anchoring. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3095. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ehrlicher A.J., Nakamura F., Stossel T.P. Mechanical strain in actin networks regulates FilGAP and integrin binding to filamin A. Nature. 2011;478:260–263. doi: 10.1038/nature10430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Engler A.J., Sen S., Discher D.E. Matrix elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pasapera A.M., Plotnikov S.V., Waterman C.M. Rac1-dependent phosphorylation and focal adhesion recruitment of myosin IIA regulates migration and mechanosensing. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vicente-Manzanares M., Newell-Litwa K., Horwitz A.R. Myosin IIA/IIB restrict adhesive and protrusive signaling to generate front-back polarity in migrating cells. J. Cell Biol. 2011;193:381–396. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201012159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borghi N., Sorokina M., Dunn A.R. E-cadherin is under constitutive actomyosin-generated tension that is increased at cell-cell contacts upon externally applied stretch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:12568–12573. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204390109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stam S., Alberts J., Munro E. Isoforms confer characteristic force generation and mechanosensation by myosin II filaments. Biophys. J. 2015;108:1997–2006. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2015.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Srivastava V., Robinson D.N. Mechanical stress and network structure drive protein dynamics during cytokinesis. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kim J.H., Ren Y., Chen E.H. Mechanical tension drives cell membrane fusion. Dev. Cell. 2015;32:561–573. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kee Y.S., Ren Y., Robinson D.N. A mechanosensory system governs myosin II accumulation in dividing cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2012;23:1510–1523. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-07-0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jana S.S., Kim K.Y., Adelstein R.S. An alternatively spliced isoform of non-muscle myosin II-C is not regulated by myosin light chain phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:11563–11571. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806574200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Beach J.R., Shao L., Hammer J.A., 3rd Nonmuscle myosin II isoforms coassemble in living cells. Curr. Biol. 2014;24:1160–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Norstrom M.F., Smithback P.A., Rock R.S. Unconventional processive mechanics of non-muscle myosin IIB. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:26326–26334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nagy A., Takagi Y., Sellers J.R. Kinetic characterization of nonmuscle myosin IIb at the single molecule level. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:709–722. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.424671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rosenfeld S.S., Xing J., Sweeney H.L. Myosin IIb is unconventionally conventional. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:27449–27455. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kovács M., Wang F., Sellers J.R. Functional divergence of human cytoplasmic myosin II: kinetic characterization of the non-muscle IIA isoform. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:38132–38140. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang F., Kovacs M., Sellers J.R. Kinetic mechanism of non-muscle myosin IIB: functional adaptations for tension generation and maintenance. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:27439–27448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302510200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Heissler S.M., Manstein D.J. Comparative kinetic and functional characterization of the motor domains of human nonmuscle myosin-2C isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:21191–21202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.212290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kovács M., Thirumurugan K., Sellers J.R. Load-dependent mechanism of nonmuscle myosin 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:9994–9999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701181104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hundt N., Steffen W., Manstein D.J. Load-dependent modulation of non-muscle myosin-2A function by tropomyosin 4.2. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:20554. doi: 10.1038/srep20554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Capitanio M., Canepari M., Bottinelli R. Two independent mechanical events in the interaction cycle of skeletal muscle myosin with actin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:87–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506830102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Finer J.T., Simmons R.M., Spudich J.A. Single myosin molecule mechanics: piconewton forces and nanometre steps. Nature. 1994;368:113–119. doi: 10.1038/368113a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Billington N., Wang A., Sellers J.R. Characterization of three full-length human nonmuscle myosin II paralogs. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:33398–33410. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.499848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Billington N., Beach J.R., Sellers J.R. Myosin 18A coassembles with nonmuscle myosin 2 to form mixed bipolar filaments. Curr. Biol. 2015;25:942–948. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arpağ G., Shastry S., Tüzel E. Transport by populations of fast and slow kinesins uncovers novel family-dependent motor characteristics important for in vivo function. Biophys. J. 2014;107:1896–1904. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Laakso, J. M. 2009. Single molecule studies of myosin-IB. PhD thesis. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sample movie from simulations showing the time-dependent position of an actin filament over a pedestal containing Myo1b, Myo1c, smooth muscle, and β-cardiac muscle myosin-II motors (σ = 20 motors/μm). The trap force is shown by springs connected to the filament ends. Motors are color-coded to show the force exerted at a given time. The look-up table for the color-coding was selected to give a dynamic range around forces of ∼1 pN. Fcutoff is the mean force plus one standard deviation that is exerted by actin-bound myosins at a given frame, averaged over all the frames. This cutoff force is 1.8 pN, 1.9 pN, 1.7 pN, and 1.7 pN for Myo1b, Myo1c, smooth muscle, and β-cardiac muscle myosin-II, respectively. Motors with forces that exceed the cut-off value are shown in green. The plots below the movie show the number of motors bound to the actin (N), the position of the actin filament, and the trap force (F), respectively. The spring constant is decreased twofold at t = 0 s.

Sample movie from simulations showing the time-dependent position of an actin filament over a pedestal containing NMIIA, NMIIB, and NMIIC motors (σ = 20 motors/μm). The trap force is shown by springs connected to the filament ends. Motors are color-coded to show the force exerted at a given time. Fcutoff is the mean force plus one standard deviation that is exerted by actin-bound myosins at a given frame, averaged over all the frames. This cutoff force is 1.4 pN, 1.4 pN, 1.3 pN and 1.6 pN for NMIIA, NMIIA+Tm, NMIIB, and NMIIC motors, respectively. Motors with forces that exceed the cut-off value are shown in green. The plots below the movie show the number of motors bound to the filament (N), the position of the actin filament, and the trap force (F), respectively. The spring constant is decreased twofold at t = 0 s. The movie is from simulations performed using the same parameters as in Fig. 4, but with different traces.