Abstract

Although the volume of living cells has been known to heavily influence their behavior and fate, a method allowing us to control the cell size in a programmable manner is still lacking. Here, we develop a technique in which precise changes in the cellular volume can be conveniently introduced by varying the voltage applied across a Nafion membrane that separates the culture medium from a reservoir. It is found that, unlike sudden osmotic shocks, active ion transport across the membrane of leukemia K562 cells will not be triggered by a gradual change in the extracellular osmolarity. Furthermore, when subjected to the same applied voltage, different lung and nasopharyngeal epithelial cancer cells will undergo larger volumetric changes and have a 5–10% higher death rate compared to their normal counterparts. We show that such distinct response is largely caused by the overexpression of aquaporin-4 in tumor cells, with knockout of this water channel protein resulting in a markedly reduced change in the cellular volume. Finally, by taking into account the exchange of water/ion molecules across the Nafion film and the cell membrane, a theoretical model is also proposed to describe the voltage-induced size changes of cells, which explain our experimental observations very well.

Introduction

Cells must maintain their volume to perform biological duties and survive. Changes in intracellular ion concentration can profoundly affect protein functions (1, 2) and, eventually, influence the fate of the cell such as proliferation and death (3, 4, 5). As such, finding ways to control the volume of cells could be important in the development of new strategies to direct their activities. Currently, the most convenient and popular way to alter the cellular volume is via osmotic shocks, that is, by the sudden addition/withdrawal of salt to/from the culture medium (6, 7, 8). Interestingly, a recent study has revealed that variations in the surrounding hydrostatic pressure can also lead to volumetric change of live cells (9). A common theme of these approaches is that, essentially, a step change to the microenvironment of cells (i.e., osmolarity or hydrostatic pressure) is introduced. However, it is unlikely that the cell volume can be controlled in a programmable manner (for example, to vary reversibly or cyclically) via such methods, a feature that is critical for interrogating and exploiting different phenomena associated with size change of cells, as well as revealing the mechanisms behind the size change.

For example, it is well-documented that active cross-membrane transport of ions will be triggered by osmotic shocks to restore (or delay) the imposed volumetric change (2, 3, 6). However, the fundamental issue of whether such so-called regulatory response of cells will be activated by a gradually varied surrounding osmolarity remains unclear. In addition, since changes in the cellular volume must involve water influx/efflux into/from the cell, the presence and functioning of membrane water channel proteins—aquaporins (AQPs)—could play an important role in this process (10, 11). As such, it is conceivable that tumor and healthy cells may respond distinctly to the same volume-changing cue given that higher expression levels of AQPs have been found in different cancer cell lines, including colorectal (12) and lung carcinoma (11, 12) cells. Evidently, finding answers to these questions will be of great interest both fundamentally and therapeutically.

In this study, we present a novel, to our knowledge, method to introduce precise changes in the cellular volume via electroosmotic manipulation. Specifically, an experimental setup, shown in Fig. 1 A (refer to Section A in the Supporting Material for fabrication details), was designed where two identical culture chambers are separated by a Nafion membrane (permeable to cations only (13, 14)). A voltage difference is then applied across the partition film, leading to a net flux of cations from one compartment to the other and eventually altering their osmolarity levels. Notice that, compared to conventional approaches (15, 16) where salts or ultrapure water were suddenly added to the culture medium, here, the extracellular osmolarity is varied in a gradual manner. To maintain the viability of cells, the whole setup is kept inside a mini-incubator (Mini incubator, Gentaur, Brussels, Belgium) with temperature (37°C) and CO2 (5%) control. We show that the magnitude of size change of suspension leukemia cells can be accurately calibrated against the applied voltage, and the process is well explained by a simple model. The technique is then used to examine the response of tumor nasopharyngeal and lung epithelial cells, along with their normal counterparts. Interestingly, it is found that active ion exchange across the membrane of these cells will not be triggered by a gradual variation in the surrounding osmolarity. In addition, due to the overexpression of aquaporin-4 (AQP4), cancer cells will undergo larger volumetric changes and have a 5–10% higher increase in the death rate.

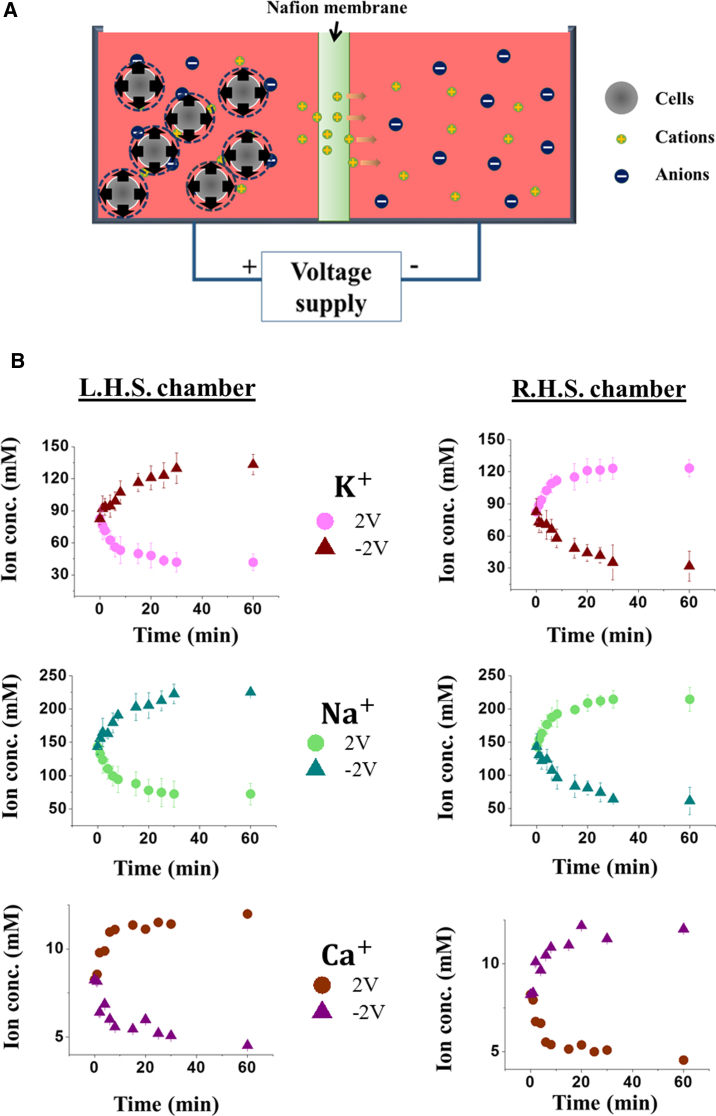

Figure 1.

(A) Schematic diagram of the experimental setup for regulating the volume of cells via electroosmotic manipulation. A Nafion membrane, permeable to cations, is used to separate two culture compartments (4 × 4 × 4 cm3 sterile polystyrene). A voltage difference was applied across the membrane to drive the movement of cations, alter the medium osmolarity, and, eventually, control the size of cells. (B) Temporal evolutions of the concentrations of Na+, K+ and Ca2+, measured by ion-selective electrodes (see Section A in the Supporting Material), in the left and right compartments. Data shown here are based on 10 independent trials where the standard deviation is represented by error bars. To see this figure in color, go online.

Materials and Methods

Please see the Supporting Materials and Methods for details.

Results

Volumetric response of suspension leukemia cells under electroosmotic manipulation

To confirm that the medium osmolarity is varying gradually in our setup, changes in the concentration of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ (three major cation species) in both chambers were monitored by ion-selective electrodes (LAQUAtwin Compact Sodium/Potassium/Calcium Ion Meter, Horiba, Kyoto, Japan). As shown in Fig. 1 B, application of the voltage will indeed induce gradual changes in the concentration levels of these cations in the culture fluid. In addition, our results also suggest that, compared to sodium and potassium, the density of calcium is an order of magnitude lower.

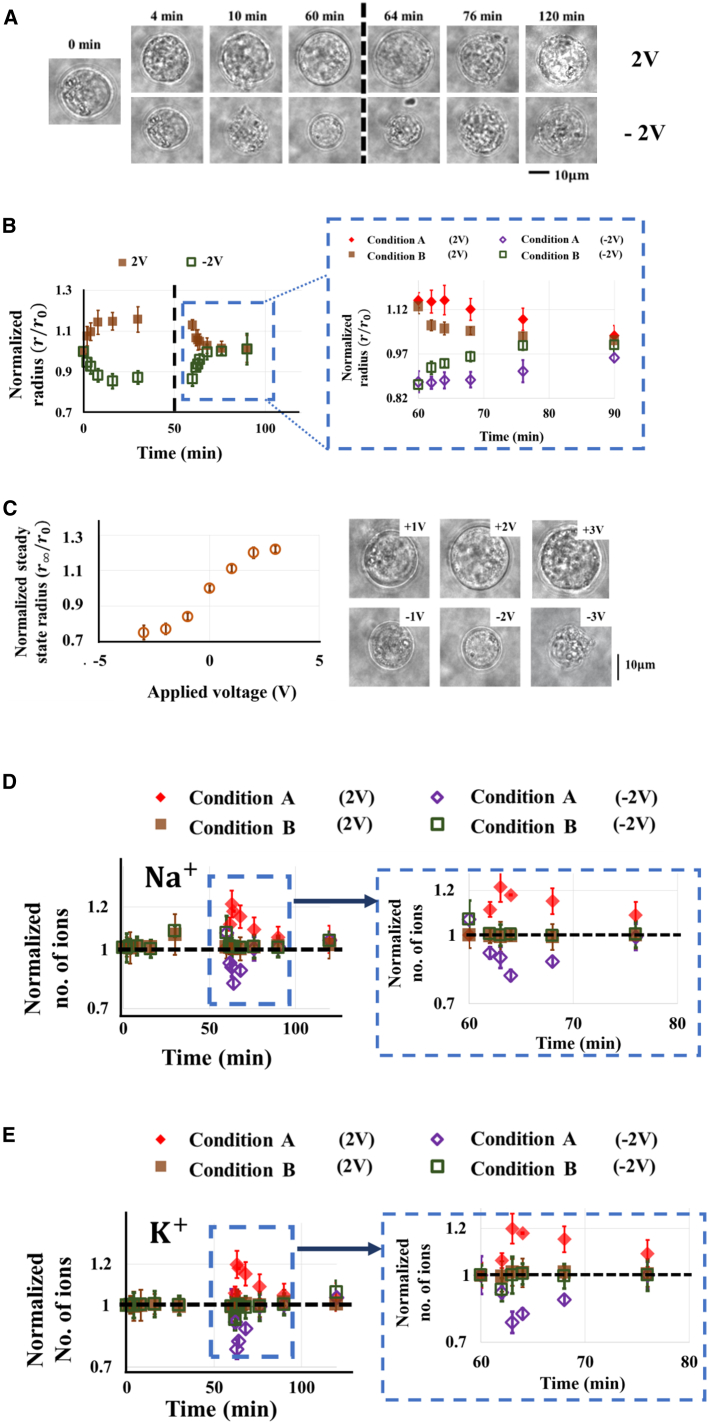

The radius evolution of chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 cells (cultured in the left chamber of our apparatus) in response to a suddenly applied voltage of 2V or −2V, which was held for 1 h before removal, is given in Fig. 2, A and B. Clearly, the cell reacts to the applied voltage by gradual swelling or shrinkage until it reaches a steady-state volume after ∼15 min. Interestingly, cells can more or less recover to their original size once the voltage is removed, suggesting that the volumetric change is reversible. The steady-state cell radius as a function of the applied voltage is given in Fig. 2 C, which shows that the size of cells varies linearly with the voltage in the range −2 V to 2 V. However, changes in the cell radius become saturated when higher voltages are used.

Figure 2.

(A) Representative micrographs showing the reversible size change of K562 cells induced by applied voltage of 2 V or −2 V, which was removed after 60 min. (B) Evolution of the mean radius of K562 cells, normalized by its initial value, r0 = 10.5 μm. The amplified plot shows how the cell radius returned to its original value when the voltage was removed after 1 h (condition B). In comparison, the size recovery of cells transferred to a fresh medium immediately after voltage treatment (condition A) is also given. (C) Steady-state cell radius as a function of the voltage amplitude. (D and E) Total number of intracellular sodium (D) and potassium (E) ions, normalized by their initial values, in K562 cells, where symbols represent the same experimental conditions as specified in (B). Cell radii shown in (B) and (C) were based on measurements on 30 cells (p < 0.05), whereas a total of 4000 cells (in two separate trials) were examined by flow cytometry to render the results given in (D) and (E), with p < 0.01. To see this figure in color, go online.

The observed volumetric change of cells was likely due to the voltage-induced transport of cations across the Nafion film, which altered the extracellular osmolarity (refer to Fig. 1 B) and eventually led to a water efflux from (or influx into) the cell. As pointed out earlier, unlike traditional approaches where sudden osmotic shocks were introduced to cells, here the osmolarity level in the culture fluid changed gradually even though the voltage was switched on in a step-function manner. As such, an interesting question that naturally arises is whether cells will respond differently to a gradual or sudden increase/decrease in the surrounding osmolarity. To address this issue, we compared the size changes of cells after voltage removal under two conditions. In the first case (condition A), cells were transferred to a glass-bottom petri dish (Nalge Nunc, Rochester, NY) containing the same medium that was used in the culture chamber initially. Note that by doing so, we effectively changed the extracellular osmolarity back to its original value in an abrupt manner. In the second approach (condition B), cells were maintained in the chamber after voltage removal, i.e., allowing the medium osmolarity to gradually recover to its initial level. Surprisingly, despite the fact that the same steady-state radius was reached eventually, the size change of the cells under Condition A became much slower compared to that under Condition B (refer to the amplified plot in Fig. 2 B).

It is well known that as a mechanism for cells to maintain their volume, cross-membrane ion exchanges could be activated in response to osmotic shocks. To test whether this is the reason for the distinct volumetric behaviors observed here, we monitored how the concentrations of intracellular potassium (K+) and sodium (Na+) (two major ion species in the cytosol) evolve using well-established protocols (17, 18) (refer to Section B in the Supporting Material for details). After that, the numbers of Na+ and K+ inside the cell can be calculated by multiplying the measured concentrations with the cellular volume. Interestingly, it was observed that the total numbers of intracellular Na+ and K+ underwent a sudden increase/decrease before returning to their original levels slowly when cells were transferred to fresh medium (i.e., condition A; refer to Fig. 2, D and E). In particular, these two numbers were found to reach their maximum/minimum within ∼3–5 min (see the amplified plots in Fig. 2, D and E), which is comparable to the characteristic time associated with the volume regulatory response of cells, i.e., ∼1–10 min, depending on cell type (2, 16). In comparison, the intracellular sodium and potassium numbers remained unchanged when cells were kept in the original chamber after voltage removal (i.e., condition B). This indicates that active cross-membrane ion exchange was not triggered in cells during gradual changes of the extracellular osmolarity, and without such ion transport, a high osmolarity differential was maintained across the cell membrane, causing more rapid water efflux/influx and faster size changes of the cells observed in Fig. 2 B. With the switching on of active cross-membrane ion transport as a response to a step change in the extracellular osmolarity by transferring cells to fresh medium, the transmembrane osmolarity differential was partially restored to the normal value, and hence, water efflux/influx and size change of the cell became slower.

Theoretical model of cell-size manipulation by electroosmotic transport

Given that the majority of cations in the medium should be monovalent cations (refer to Fig. 1 B), the cation flux I(t) across the Nafion membrane can be approximately expressed as (19)

| (1) |

where G and h are the conductance and thickness of the film, quantities that have been measured recently (14, 20), Φ0 is the cross-membrane electrical potential difference, and cL+ and cR+ are the concentrations of cations in the left and right compartments, respectively. Note that in addition to cations, there will also be anions and macromolecules in the culture fluid that cannot pass through the Nafion membrane. As such, we denote cL and cR as the concentrations of all ions in the two chambers. In this case, the evolution of cL+ can be described by

| (2) |

with e, Am, and VL being the unit charge of an electron, the total area of the Nafion membrane, and the fluid volume in the left compartment. In addition to cation translocation, transport of water molecules will also be triggered in this process, leading to a rate change of VL of the form (19)

| (3) |

where the first bracketed term on the righthand side corresponds to the flow induced by cross-membrane hydrostatic and osmotic pressure differences, whereas the second term comes from the fact that when passing through the membrane, ions will drag water molecules along with them. Here, ρ is the density of water, g is the gravitational acceleration, Ac is the horizontal cross-sectional area of the two (identical) chambers, and Lp and β stand for the water and electroosmotic permeability of the Nafion membrane, respectively. It must be pointed out that our observations and simulations all suggest that changes in VL are very small (<1–2%) and hence can be neglected.

With the evolution of cL+ at hand, the volumetric change of cells can then be determined by tracking the water efflux from (or influx into) the cell (9). Specifically, treating the cell as a droplet enclosed by an elastic membrane layer, permeable to water molecules only, its size change can be described by

| (4) |

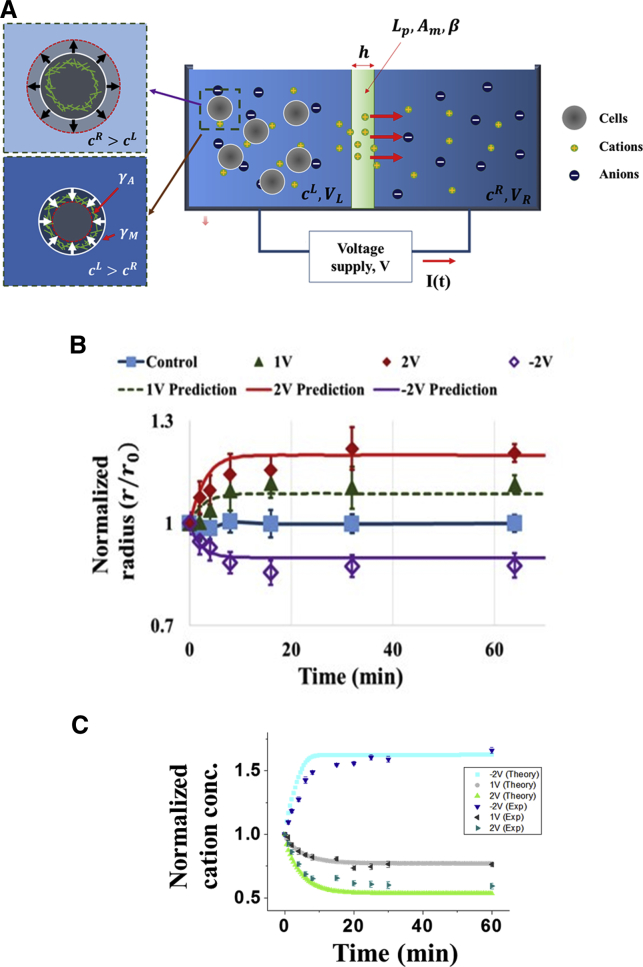

where Lw is the water permeability of the cell membrane, is the initial intracellular ion concentration, γ stands for the membrane tension, and r and r0 represent the cell radius after and before the voltage is applied. Note that here, no ion exchange is assumed to take place across the cell membrane, as suggested by our observations (Fig. 2, D and E). Similar to the methods in (5, 9), we proceed by assuming γ = γA + γM, where γA is the constant tension generated by active actomyosin contraction and corresponds to the passive stress from the deformation of the cell cortex (Fig. 3 A), with K and ru being the so-called area expansion modulus of the membrane (21) and the radius of an “unstretched” cell, respectively. The values of all parameters adopted in this study, compared favorably to those reported in the literature, are gathered in Table S1. We must point out that because of ion shielding, the cross-membrane potential difference defined in Eq. 1 is different from the applied voltage, and hence, direct measurement of Φ0 was conducted in this study (Fig. S3 in Section C). In addition, the initial cation concentration in both chambers was taken to be 380 mM, higher than the measured value of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ together (∼236 mM; refer to Fig. 1 B), which is reasonable given that the culture fluid contains many other cation species.

Figure 3.

(A) Schematic diagram illustrating how cells respond to electroosmotic manipulation. When a positive voltage is given, the cations travel from the left to the right compartment, resulting in cL < cR, and hence, the cells swell according to the decreased surrounding osmolarity. Alternatively, when a negative voltage is given, cL > cR, the cells shrink accordingly. (B) Size change of K562 cells triggered by the applied voltage. Measurement data are represented by markers, whereas theoretical predictions are obtained by choosing the parameters shown in Table S1. (C) Normalized concentration of cations in the left chamber (i.e., cL+), as a function of time, under different applied voltage. Data shown here are based on measurements of Na+, K+, and Ca2+ (assuming that the density of other cation species follows the same percentage change; refer to Fig. 1B). To see this figure in color, go online.

The predicted cell radii, as functions of time under different voltages, are plotted in Fig. 3 B along with the measurement data. Furthermore, temporal evolution of cL+ (normalized by its initial value, 380 mM) is also shown in Fig. 3 C. Clearly, a good match between theory and experiment has been achieved.

Cancer cells show greater volumetric response to electroosmotic manipulation due to the overexpression of water channel protein aquaporin 4

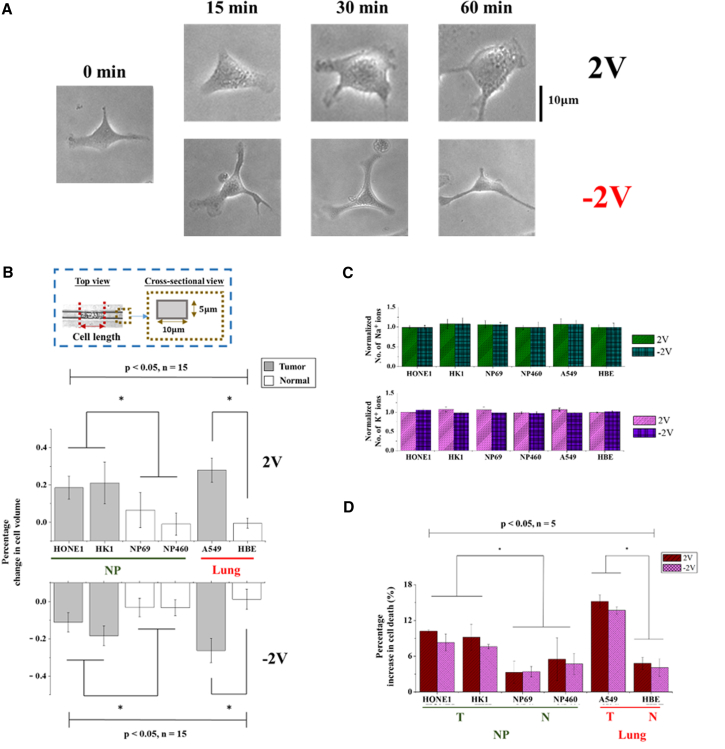

To explore the idea of whether the technique developed here can be used to direct the behavior of living cells for potential clinical applications, we proceeded to examine the response of one lung (A549) and two nasopharyngeal epithelial carcinoma (HONE1 and HK1) cell lines (refer to Section D in the Supporting Material), along with one immortalized normal lung (HBE) and two immortalized normal nasopharyngeal cell lines (i.e., NP69 and NP460), under an applied voltage of 2 V or −2 V for 60 min. Micrographs showing the morphology of A549 cells at different time points of voltage treatment are given in Fig. 4 A. To monitor the volume change of these adherent cells, trypsinization was carried out and the detached cells were then forced to flow through microchannels of 10 μm in width and 5 μm in depth (see Fig. 4 B and Section E in the Supporting Material) where the cellular volume can be conveniently estimated from the cell length. Interestingly, it was found that, compared to their normal counterparts, carcinoma cells underwent larger swelling/shrinkage under the same applied voltage (Fig. 4 B). However, similar to suspension K562 cells, the total numbers of Na+ and K+ (measured by the protocol detailed in Section B in the Supporting Material) in all the cell types examined here remained almost the same after the voltage treatment (Fig. 4 C), suggesting that a much more pronounced change in the concentration level of these intracellular ions was induced in cancer cells than in the corresponding normal ones. As such, it is conceivable that the applied voltage will alter the behavior of tumor cells more significantly. Indeed, a noticeable increase in the death rate, evaluated by propidium iodide (PI) assay (Section F in the Supporting Material), was found among cancer cells (Fig. 4 D) after 1 h voltage treatment.

Figure 4.

(A) Micrographs showing the morphological changes of A549 cells under the applied voltage. (B) Histogram showing the percentage volume change of nasopharygneal carcinoma (HONE1 and HK1), lung carcinoma (A549), immortalized normal nasopharyngeal (NP69 and NP460), and immortalized normal lung (HBE) cell lines after 1 h voltage treatment. Note that the cellular volume is estimated from the length of cells in microchannels with a cross section shown in the inset. Here, n indicates the number of independent measurements and ∗p < 0.05 from the paired t-test. (C) Bar graph illustrating the change of total intracellular Na+ and K+ numbers in different carcinoma and normal cell lines, with triplicate tests carried out in each case. (D) Percentage increase in the death population of cells under an applied voltage of 2 V and −2 V, respectively, where 10,000 cells were examined in each trial. To see this figure in color, go online.

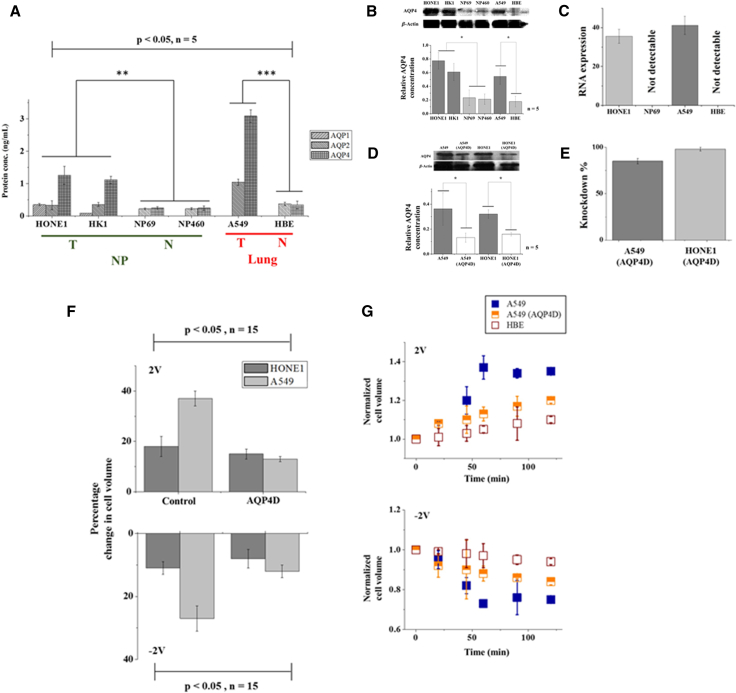

Given that changes in the cellular volume must involve water influx/efflux into/from the cell, the distinct response exhibited by carcinoma and normal cells may be due to the different expression levels of water channel proteins—AQPs (10, 11)—in their membranes. In fact, four types of aquaporins (i.e., AQP1, AQP2, AQP3, and AQP4) have been found to exist in human nasopharyngeal and lung carcinoma cell lines (10, 22, 23), with AQP1, AQP2, and AQP4 mainly responsible for cytoplasmic water transport, whereas AQP3 also participates in the cross-membrane exchange of glycerol and possibly other small solutes (24, 25). We proceeded by focusing on AQP1, AQP2, and AQP4, and performing the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to estimate their concentrations (Section G in the Supporting Material) in various cell lines. Interestingly, significantly more AQPs were found in carcinoma cells than in their normal counterparts, and AQP4 was the most abundant among them (Fig. 5 A). To further confirm this, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR; Section H in the Supporting Material) and Western blotting (Section I in the Supporting Material) were also conducted to determine the density of AQP4 in nasopharyngeal (HONE1 and HK1) and lung (A549) carcinoma cell lines versus their normal counterparts (NP69, NP460, and HBE), and RNA expression in HONE1 versus NP69 and A549 versus HBE pairs. Again, results from these tests demonstrate that the expression level of AQP4 in normal cells is much lower than that in cancerous ones (Fig. 5, B and C).

Figure 5.

(A) Concentrations of water channel proteins AQP1, AQP2, and AQP4 in carcinoma (HONE1, HK1, and A549) and normal (NP69, NP460, and HBE) cell lines determined by ELISA assay quantification. ∗∗p < 0.01 and ∗∗∗p < 0.001; n represents the number of independent trials where 3 × 106 cells were examined in each trial. (B) (Top) Western blotting showing the expression level of AQP4 in different cell lines. (Bottom) Densitometric quantification of the Western blotting bands. The values of AQP4 are normalized against β-actin for each sample (n = 5/group, ∗p < 0.05). Here, β-actin is served as the loading control reprobed by stripping. (C) RNA expression of AQP4 in HONE1 versus NP69 and A549 versus HBE cell line pairs evaluated by qPCR. (D) (Top) Expression levels (from Western blotting) of AQP4 in AQP4-knockout A549 and HONE1 cells, as well as in their parental cell lines, treated with empty liposomes. (Bottom) Densitometric quantification of the Western blotting bands. The values of AQP4 are normalized against β-actin for each sample (n = 5/group, ∗p < 0.05). (E) The efficiency of AQP4 knockdown evaluated by qPCR. (F) Histogram showing the percentage change in the volume of lung carcinoma (A549) and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (HONE1) cell lines with AQP4 knockdown by small interfering RNA (AQP4D), along with cells treated with empty liposomes (Control), under an applied voltage of 2V or -2V for 60 min. (G) Temporal evolution of the normalized volume of carcinoma (A549), normal (HBE), and AQP4-knockout tumor (AQP4D A549) cells under an applied voltage of 2V and −2V, respectively. Data shown here were based on measurements on 30 cells (p < 0.05). To see this figure in color, go online.

Next, we knock down the AQP4 channels in HONE1 and A549 cells by small interfering RNA (refer to Section J in the Supporting Material for details) and then monitor how these genetically modified cells respond to the imposed electroosmotic manipulation. Successful AQP4 knockout was confirmed by western blotting (Fig. 5 D) as well as qPCR (Fig. 5 E). As shown in Fig. 5 F, deletion of the AQP4 gene resulted in a reduced volume change (by at least ∼20%) of carcinoma cell lines under the same applied voltage. Furthermore, the size change of AQP4-deleted A549 cells, in this case, became more comparable to that exhibited by the corresponding normal HBE cell line (Fig. 5 G). In light of our model, this interesting finding can be understood by realizing that the water permeability (Lw) of the cell membrane will be greatly reduced if all AQP4 channels have been knocked out, which, eventually, leads to much slower changes of the cellular volume.

We must point out that cells were immediately transferred from one device to another in the solution form when their volume, ion concentrations, and death population were measured. Furthermore, the transfer process was conducted inside the incubator with temperature and CO2 controlled to limit any possible change of cell state during the manipulation. Indeed, as demonstrated by our control experiments (Fig. 3 B; Fig. S4), the size and intracellular contents of cells will remain unchanged during the test if no voltage is applied. Finally, because the experimental setup was designed and used for the first time, to our knowledge, special attention has been paid to make sure that findings and conclusions obtained are valid and robust. Specifically, in addition to a series of control experiments mentioned above, results presented here are based on a relatively large number of independent measurements, and a statistical confidence of no less than 95% has been achieved in all cases (refer to Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5).

Discussion

In this study, we introduce a novel, to our knowledge, method was developed by which to regulate the volume of live cells via electroosmotic manipulation. Specifically, using a Nafion membrane to separate the cell-culture chamber from a medium reservoir, we demonstrated that translocation of cations across the Nafion film can be induced by an applied voltage, leading to a gradually varied extracellular osmolarity and eventually size change of the cell. Furthermore, we showed that the magnitude of volume reduction/increase of cells can be accurately calibrated against the voltage and the deformation process is well described by a simple model that takes into account cross-membrane exchange of ions and water molecules. Compared to traditional approaches, in which the size change of the cells is often triggered by the sudden addition/withdrawal of salt to/from the culture medium, the technique presented here allows us to control the cell volume in a programmable manner and hence could serve as a powerful tool in regulating the progression of various cellular processes and helping to elucidate the mechanisms behind these processes.

In particular, we showed that no apparent cross-membrane transport of Na+ and K+ in chronic myelogenous leukemia K562 and various epithelial cells took place when a gradual change in the surrounding osmolarity was introduced. It must be pointed out that recent experiments have convincingly demonstrated that various cell-volume regulatory ion channels, such as VRAC and Piezo, can all be activated if the membrane tension reaches a threshold value (26, 27). As such, our finding suggests that the tension level within the cell membrane is not high enough to trigger these channels during the electroosmotic manipulation. One possible explanation is that the swelling-induced stretching of the cell membrane may have been offset by lipid renewal (via endo- and exocytosis for example). Indeed, it has been reported that endocytosis has a half-life of 10–60 s (28, 29), and that exocytosis appears to take place on a timescale of ∼100 s (30); both are much faster than the volumetric deformation of cells in our experiment. In addition, to make sure that the appearance of the electric field does not interfere with the functioning of ion channels; and hence influence our conclusion, we have conducted an additional experiment where a microfluidic mixer was used to add sucrose to the culture medium at different perfusion rates (refer to Section K in the Supporting Material). Interestingly, a similar decrease in the volume of K562 cells (compared to that shown in Fig. 2) was observed. Furthermore, despite some fluctuations, no apparent change in the total number of intracellular Na+ and K+ was detected during this process (see Fig. S6), further supporting the notion that no cross-membrane ion exchange will be triggered by a gradually varied extracellular osmolarity.

More interestingly, it was found that, under the same applied voltage, cancerous nasopharyngeal (HONE1 and HK1) and lung (A549) epithelial cells will undergo larger volumetric changes and exhibit a more pronounced increase in the death rate compared to their normal counterparts (i.e., NP69 and NP460, and HBE cells). We further demonstrated that the distinct volumetric response observed here is largely due to the overexpression of water channel protein AQP4 in tumor cells. In particular, genetic knockdown of AQP4 leads to a considerably reduced volume change (by at least ∼20%) in cancer cells. The high death rate among carcinoma cell lines under voltage treatment is likely due to larger changes in the concentration of intracellular content (recall that tumor cells undergo more severe volumetric deformations). For example, it is well-documented that apoptosis will be triggered when cells are dehydrated or under prolonged exposure to hypertonic environment (3, 6). On the other hand, evidence has also shown that hypoosmotic stress can lead to necrotic cell death (31, 32). Although the exact mechanisms remain to be determined, our study clearly demonstrated that selective killing of epithelial cancer cells might be achieved through electroosmotic manipulation. Whether similar findings will be obtained on other types of tumor cells and whether the technique developed here can lead to potential clinical applications are all questions of great interest.

Finally, in addition to providing a physical explanation for the observed volumetric response of cells, as well as identifying important factors governing this process, the model developed here could also be useful in the design and interpretation of future experiments. For example, key quantities such as the membrane permeability of different suspension cells, which are hard (if not impossible) to measure biochemically, can be estimated by comparing theory with experiment. In addition, model predictions can provide guidance for the temporal profile of the applied voltage for achieving desirable size evolution of cells.

Author Contributions

Y.L. and A.H.W.N. designed research; T.H.H., K.W.K, H.W.F. and M.Y. performed research; T.T.C.Y., K.C.N. and S.Y. contributed analytic tools; T.H.H., K.W.K, H.W.F., M.Y., A.H.W.N., and Y.L. analyzed data; and T.H.H., K.W.K., T.T.C.Y., K.C.N., S.Y., A.H.W.N., and Y.L. wrote the article.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Research Grants Council (project nos. HKU 714312E, HKU 714713E, and HKU 17205114) of the Hong Kong Special Administration Region and from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (project no. 11572273). A.H.W.N. gratefully acknowledges support from the Kingboard Endowed Professorship fund.

Editor: Ewa Paluch.

Footnotes

T. H. Hui and K. W. Kwan contributed equally to this work.

Supporting Materials and Methods, six figures, and one table are available at http://www.biophysj.org/biophysj/supplemental/S0006-3495(16)30288-0.

Contributor Information

Alfonso Hin Wan Ngan, Email: hwngan@hku.hk.

Yuan Lin, Email: ylin@hku.hk.

Supporting Citations

References (33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Miermont A., Waharte F., Hersen P. Severe osmotic compression triggers a slowdown of intracellular signaling, which can be explained by molecular crowding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:5725–5730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215367110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann E.K., Lambert I.H., Pedersen S.F. Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiol. Rev. 2009;89:193–277. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00037.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lang F. Mechanisms and significance of cell volume regulation. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2007;26(5 Suppl):613S–623S. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2007.10719667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hall D., Hoshino M. Effects of macromolecular crowding on intracellular diffusion from a single particle perspective. Biophys. Rev. 2010;2:39–53. doi: 10.1007/s12551-010-0029-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang H., Sun S.X. Cellular pressure and volume regulation and implications for cell mechanics. Biophys. J. 2013;105:609–619. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yurinskaya V.E., Rubashkin A.A., Vereninov A.A. Regulatory volume increase (RVI) and apoptotic volume decrease (AVD) in U937 cells in hypertonic medium. Cell Tissue Biol. 2011;5:487–494. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhou E.H., Trepat X., Fredberg J.J. Universal behavior of the osmotically compressed cell and its analogy to the colloidal glass transition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:10632–10637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901462106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi J., Kundrat L., Lodish H.F. Engineered red blood cells as carriers for systemic delivery of a wide array of functional probes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:10131–10136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409861111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui T.H., Zhou Z.L., Gao H. Volumetric deformation of live cells induced by pressure-activated cross-membrane ion transport. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014;113:118101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.113.118101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verkman A.S., Hara-Chikuma M., Papadopoulos M.C. Aquaporins—new players in cancer biology. J. Mol. Med. 2008;86:523–529. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0303-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verkman A.S., Anderson M.O., Papadopoulos M.C. Aquaporins: important but elusive drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:259–277. doi: 10.1038/nrd4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moon C., Soria J.-C., Mao L. Involvement of aquaporins in colorectal carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2003;22:6699–6703. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morris D.R., Sun X. Water-sorption and transport properties of Nafion 117 H. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1993;50:1445–1452. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stenina I.A., Sistat P., Yaroslavtsev A.B. Ion mobility in Nafion-117 membranes. Desalination. 2004;170:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pedersen S.F., Hoffmann E.K., Novak I. Cell volume regulation in epithelial physiology and cancer. Front. Physiol. 2013;4:233. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lambert I.H., Hoffmann E.K., Pedersen S.F. Cell volume regulation: physiology and pathophysiology. Acta Physiol. (Oxf.) 2008;194:255–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2008.01910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meuwis K., Boens N., Vincent M. Photophysics of the fluorescent K+ indicator PBFI. Biophys. J. 1995;68:2469–2473. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80428-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin V.V., Rothe A., Gee K.R. Fluorescent metal ion indicators based on benzoannelated crown systems: a green fluorescent indicator for intracellular sodium ions. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005;15:1851–1855. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanaka Y. Elsevier; Amsterdam, the Netherlands: 2007. Membrane Science and Technology. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Okada T., Møller-Holst S., Kjelstrup S. Transport and equilibrium properties of Nafion® membranes with H+ and Na+ ions. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1998;442:137–145. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boal D. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, United Kingdom: 2002. Mechanics of the Cell. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xie Y., Wen X., Dai L. Aquaporin 1 and aquaporin 4 are involved in invasion of lung cancer cells. Clin. Lab. 2012;58:75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H., Li H., Wang L. The AQP-3 water channel and the ClC-3 chloride channel coordinate the hypotonicity-induced swelling volume in nasopharyngeal carcinoma cells. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2014;57:96–107. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clegg J.S. Properties and metabolism of the aqueous cytoplasm and its boundaries. Am. J. Physiol. 1984;246:R133–R151. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1984.246.2.R133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clegg J.S. Intracellular water and the cytomatrix: some methods of study and current views. J. Cell Biol. 1984;99:167s–171s. doi: 10.1083/jcb.99.1.167s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cox C.D., Bae C., Martinac B. Removal of the mechanoprotective influence of the cytoskeleton reveals PIEZO1 is gated by bilayer tension. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10366. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Syeda R., Qiu Z., Patapoutian A. LRRC8 proteins form volume-regulated anion channels that sense ionic strength. Cell. 2016;164:499–511. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rappoport J.Z., Simon S.M. Real-time analysis of clathrin-mediated endocytosis during cell migration. J. Cell Sci. 2003;116:847–855. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryan T.A., Smith S.J., Reuter H. The timing of synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:5567–5571. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.11.5567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran D.T., Masedunskas A., Ten Hagen K.G. Arp2/3-mediated F-actin formation controls regulated exocytosis in vivo. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:10098. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moeckel G.W. Hypertonic stress and cell death. Focus on “Multiple cell death pathways are independently activated by lethal hypertonicity in renal epithelial cells”. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C1009–C1010. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00263.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niquet J., Allen S.G., Wasterlain C.G. Evidence of caspase-3 activation in hyposmotic stress-induced necrosis. Neurosci. Lett. 2004;356:225–227. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balzer E.M., Tong Z., Konstantopoulos K. Physical confinement alters tumor cell adhesion and migration phenotypes. FASEB J. 2012;26:4045–4056. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-211441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu M., Hou Y., Yao S. An on-demand nanofluidic concentrator. Lab Chip. 2015;15:1524–1532. doi: 10.1039/c4lc01480d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benjamini Y., Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Canales R.D., Luo Y., Goodsaid F.M. Evaluation of DNA microarray results with quantitative gene expression platforms. Nat. Biotechnol. 2006;24:1115–1122. doi: 10.1038/nbt1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cividalli G., Nathan D.G. Sodium and potassium concentration and transmembrane fluxes in leukocytes. Blood. 1974;43:861–869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cameron I.L., Smith N.K.R., Sparks R.L. Intracellular concentration of sodium and other elements as related to mitogenesis and oncogenesis in vivo. Cancer Res. 1980;40:1493–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farinas J., Verkman A.S. Cell volume and plasma membrane osmotic water permeability in epithelial cell layers measured by interferometry. Biophys. J. 1996;71:3511–3522. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79546-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hochmuth R.M. Micropipette aspiration of living cells. J. Biomech. 2000;33:15–22. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(99)00175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fuller T.F., Newman J. Experimental determination of the transport number of water in Nafion 117 membrane. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1992;139:1332–1337. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.