Abstract

This work reports on the construction of a Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction via a simple thermal annealing method. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) results indicated that the phase transformation from BiOCl to Bi24O31Cl10 could be realized during the thermal annealing process. The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) binding energy shifts, Raman spectra and Fouier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) spectra confirmed the formation of the Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction. The obtained Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl photocatalyst showed excellent conversion efficiency and selectivity toward photocatalytic conversion of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde under visible light irradiation. The radical scavengers and electron spin resonance (ESR) results suggested that the photogenerated holes were the dominant reactive species responsible for the photocatalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol and superoxide radicals were not involved in the photocatalytic process. The in-situ generation of Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction may own superior interfacial contact than the two-step synthesized heterojunctions, which promotes the transfer of photogenerated charge carriers and is favorable for excellent photocatalytic activities.

Regarding the future environmental and energy concerns, the development of green and sustainable chemical conversions has attracted enormous interest1,2,3. Alcohol oxidations are one of the most frequently investigated reactions because of their industrial essentiality in the commercial synthesis of multifarious materials, such as plastics, perfumes, paints, etc4,5,6. Compared with conventional methods, photocatalytic technology is considered to be a green, reliable and economic method for the oxidation of alcohols into the corresponding aldehydes due to the massive solar energy and O27,8,9,10,11.

Semiconductor titanium dioxide (TiO2) is universally regarded as an efficient photocatalyst toward decomposition of various organic pollutants12,13,14,15,16,17. Moreover, it also displays photocatalytic activity toward the oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde under UV-light and visible-light irradiation, which shows high conversion efficiency (>99%) and selectivity (>99%)18,19. Recently, considerable attention has been devoted to another series of semiconductors, the bismuth-based semiconductors. BiOCl is a V-VI-VII ternary semiconductor, consisting of internal structure of [Bi2O2]2+ layers sandwiched by two slabs of Cl atoms which induces the growth of BiOCl along a particular axis20. It often shows high photocatalytic performance than TiO2 (P25, Degussa) under UV-light irradiation due to its unique layered atomic structure, which favors the transfer and separation of photogenerated charge carriers and subsequently enhances the photocatalytic activity21,22. However, BiOCl is a wide-band-gap (3.17 ~ 3.54 eV) semiconductor23,24, which leads to a poor photocatalytic performance under visible light irradiation.

Constructing heterojunction composed of BiOCl and another narrow band-gap semiconductor with suitable conduction band (CB) and valence band (VB) can efficiently improve the visible-light harvesting and inhibit the electron-hole recombination as well as raise the lifetime of charge carriers. A variety of heterojunction systems containing BiOCl and a narrow band-gap semiconductor has been intensively investigated, e.g. g-C3N4/BiOCl25, Bi2S3/BiOCl26, BiOI/BiOCl27, CdS/BiOCl28, WO3/BiOCl29, BiVO4/BiOCl30, NaBiO3/BiOCl31, etc. All these heterojunctions presented enhanced photocatalytic performances than their single-component counterparts.

From the viewpoint of solid state physics, details of the band edge potential are primarily determined by the static potential within the unit cell of a semiconductor32. Any symmetry and component perturbations can have consequence on the electronic structures and physical properties. Since the potential of conduction band minimum (CBM) and valence band maximum (VBM) are mainly related to Bi 6p and Bi 6s orbitals respectively, the regulation of CBM and VBM of bismuth-based semiconductors can be achieved by adjusting the Bi content33,34. Recently, nontypical stoichiometric semiconductors (NSSs), including Bi3O4Cl35, Bi12O15Cl636, Bi24O31Cl1033 have been found to show visible light driven photocatalytic activities, which are regarded as ideal candidates for the construction of heterojunctions with BiOCl. These NSSs have narrower band gap, faster transfer of charge carriers and more efficient separation of photogenerated electron-hole pairs37. Furthermore, they have the approximate crystalline architecture relative to their corresponding typical stoichiometric semiconductors (TSSs). As a nontypical stoichiometric bismuth-based semiconductor, Bi24O31Cl10 is widely known as a product of the thermal decomposition of BiOCl38. It has a narrow band gap of about 2.7 ~ 2.8 eV33,39, demonstrating a good visible-light harvesting. Thus, Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction may be a promising photocatalyst in the visible light region, if both of them have the suitable CB and VB levels40.

In the present study, Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction was constructed via a in-situ fabrication. Although Bi24O31Cl10 is widely known as a thermal decomposition product of BiOCl, the structure and the photocatalytic performance of the intermediate product Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction were not investigated in detail. The oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde is firstly chosen as the model reaction to check the photocatalytic performance of the Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction. The in-situ fabrication of Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction may predict more interfacial contact for efficient charge carriers separation37, resulting in highly enhanced photocatalytic performance toward benzyl alcohol oxidation.

Results and Discussion

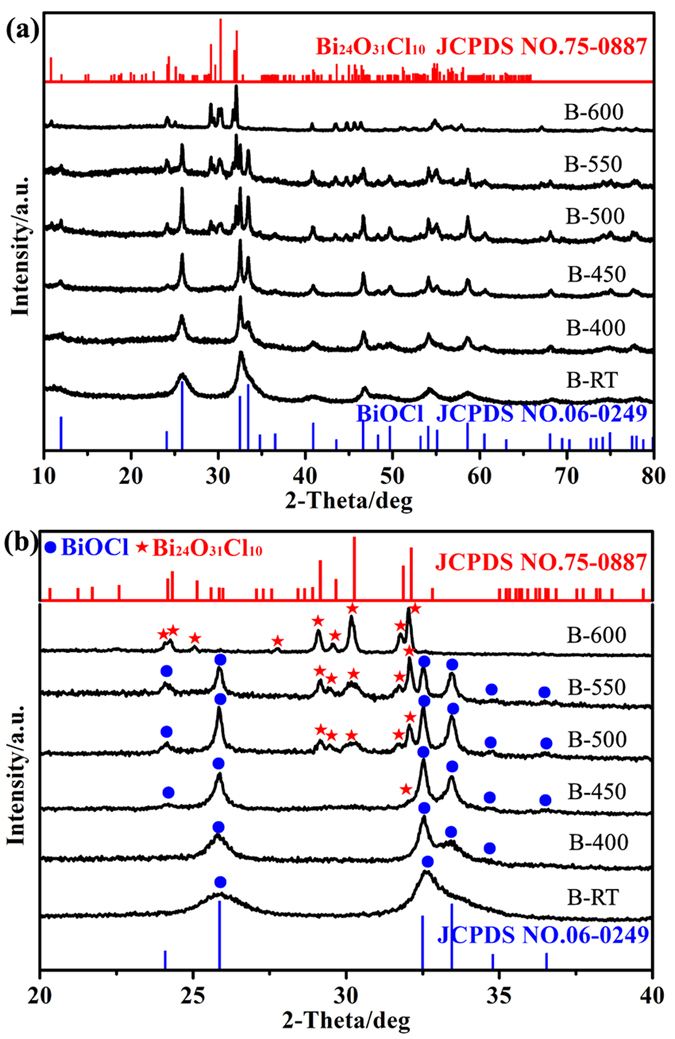

Figure 1 displays the XRD patterns of BiOCl and the calcined samples. The XRD pattern of sample B-RT is assigned to tetragonal BiOCl (JCPDS NO. 06-0249). With an increase of annealing temperature, the XRD peaks belonging to Bi24O31Cl10 with a monoclinic structure (JCPDS NO. 75-0887) emerges. No apparent diffraction peaks belonging to BiOCl are observed when the temperature increased up to 600 °C. The enlarged XRD patterns of all samples in the range of 2θ = 20 ~ 40° are also presented to further verify the transformation process from tetragonal BiOCl to monoclinic Bi24O31Cl10 (Fig. 1b). A weak peak located at 32° is assigned to Bi24O31Cl10 in XRD pattern of sample B-450. The other three typical strong peaks nearby 30° are observed in sample B-500, which indicates that large amount of Bi24O31Cl10 is produced at reaction temperature of 500 °C. Further increase of reaction temperature induces the emergence of more diffraction peaks belonging to Bi24O31Cl10 and all the XRD peaks belonging to Bi24O31Cl10 phase are only left at 600 °C (B-600). On the other hand, no XRD peak of Bi24O31Cl10 phase is observed in sample B-400, which may suggest that no observable phase transformation occurs or the Bi24O31Cl10 does not possess sufficient long-range order to be checked by XRD. DTA-TG curves (Figure S1) of sample B-RT shows that there is an exothermic peak at about 400 °C, suggesting that the phase transformation of BiOCl occurs as the temperature achieving to 400 °C, which result is consistent with the XRD results.

Figure 1. Wide and enlarged XRD patterns of various samples.

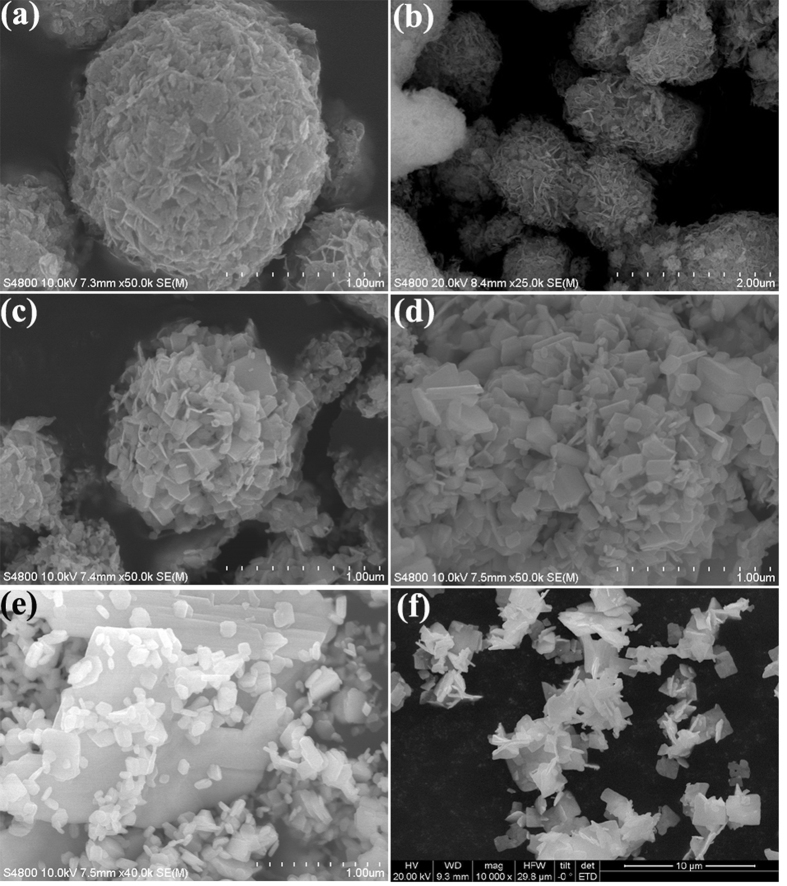

Figures 2 and S2 shows the SEM images of various samples. The image in Fig. 2a displays that the pure BiOCl spheres with diameter of about 1.5 ~ 2.0 μm are mainly consisted of irregular nanosheets, which are 0.1 ~ 0.2 μm in width and 3 ~ 5 nm in thickness (Figure S2a). After calcination at 400 °C, the nanosheet edges and angles of sample B-400 are distinct and differentiable (Fig. 2b). The gradual increased temperature leads to the morphological transformation from compact sphere to loose structure as well as irregular nanosheets to square analogs (Fig. 2c,d). Furthermore, the nanosheets of BiOCl become wider and thicker with an increase of annealing temperature. Sample B-600 (pure Bi24O31Cl10) presents square-like plate structure with 1 ~ 2μm in width and ~0.1 μm in thickness (Figs 2f and S2b). It could also be observed that the sheet-shaped structure with narrower width and thinner thickness decreases, while the plate-shaped structure increases by elevating the annealing temperature, which result is consistent with the BET results (Figure S3) that sample B-600 has the lower specific surface area (SBET) than sample B-RT.

Figure 2.

SEM images of B-RT (a), B-400 (b), B-450 (c), B-500 (d), B-550 (e), B-600 (f).

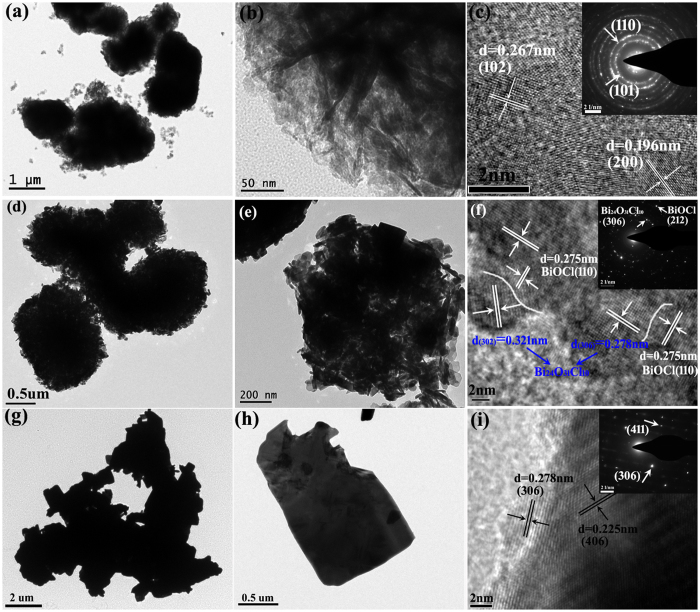

The detailed morphologies, crystal structures and the heterojunction features of samples B-RT, B-450 and B-600 are characterized by TEM, HRTEM and SAED. Figure 3a,b reveal that BiOCl spheres are composed of irregular nanosheets, which is consistent with the SEM observation (Fig. 2a). HRTEM image in Fig. 3c discloses that the distances between the adjacent lattice fringes are about 0.267 and 0.196 nm, matching well with the (102) and (200) crystalline plane of BiOCl, respectively. The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) (Inset of Fig. 3c) clearly presents the crystalline planes of (101) and (110) of BiOCl, respectively. Sample B-450 keeps the same diameter, but the shape of the nanosheets becomes regular (Fig. 3d,e). Figure 3f provides a comprehensive information of the Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction. The lattice fringes with the d spacing of 0.275 nm correspond to the (110) crystalline plane of BiOCl, whereas the lattice fringes with the d spacing of 0.321 and 0.278 nm belong to the (30-2) and (306) crystalline plane of Bi24O31Cl10, respectively. Furthermore, as displayed in Fig. 3f that there exists an identifiable interface (presented by white line) and continuity of the lattice fringes between BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10, indicating the formation of a heterojunction between the two semiconductors. The SAED pattern (Inset of Fig. 3f) further confirms the coexistence of BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10. Figure 3g,h reveal that sample B-600 displays a square-like structure and no apparent BiOCl spheres are observed. Both the HRTEM image and the SAED pattern in Fig. 3i indicate the single-crystalline characteristic of Bi24O31Cl10.

Figure 3.

TEM, HRTEM images and SAED patterns of samples B-RT(a–c), B-450 (d–f) and B-600 (g–i).

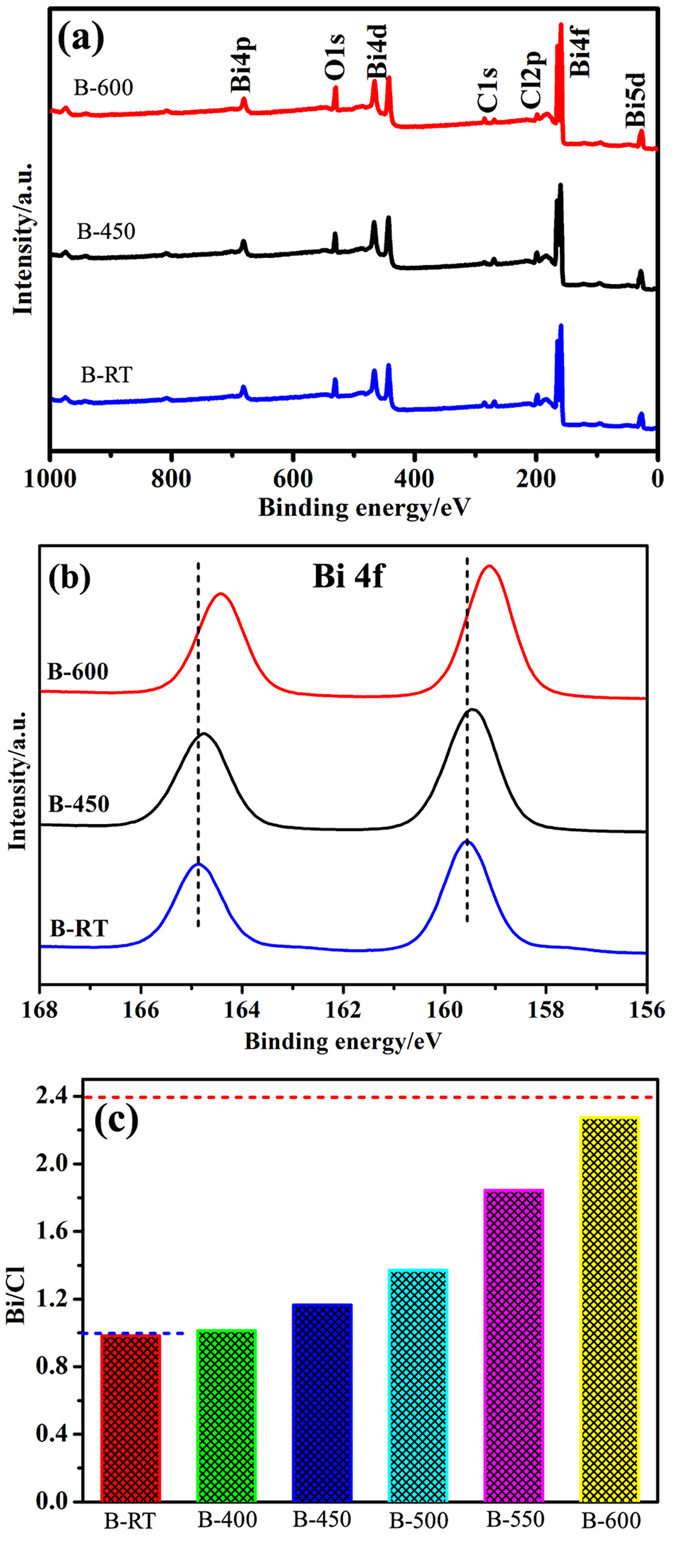

To further confirm the chemical state and chemical composition of the as-prepared samples, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis was applied and the results are shown in Fig. 4. The survey scans of samples B-RT, B-450 and B-600 distinctly reveal the co-existence of Bi, O and Cl elements without other impurities, excluding adventitious carbon-based contaminant. The two primary peaks at ~159.0 eV and ~164.0 eV in Bi 4f XPS spectra result from the spin orbital splitting photoelectrons of Bi 4f7/2 and Bi 4f5/2, respectively41. There is an obvious red-shift in the Bi 4f binding energy with increasing the temperature to 600 °C. Variations in the elemental binding energies are generally related to the difference in chemical potential and polarizability of involved elements42,43. Thus, the binding energy shift in sample B-450 is possibly attributed to the interaction between BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10, which result is similar to the SnO2−x/g-C3N444 and TiO2/ZnPcGly45. It is reported that the increase or decrease in electron concentration could enhance or reduce the electron screening effect, which would weaken or strengthen the binding energy46. The higher electronegativity of Bi could induce increased electron concentration in the new formed bonds37, such as Bi-Cl or/and Bi-O bands at the interface, which enhances the electron screening effect and leads to the Bi 4f peaks shift toward lower binding energy. Furthermore, the position of Bi 4f peaks in sample B-600 is also different from that in sample B-RT, which could be attributed to the different chemical environment of Bi ions in BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10. This observation is in accordance with the XPS results of BiOCl/Bi12O15Cl636 and BiVO4/Bi4V2O1137. However, the span between the two binding energy peaks maintains the same value of 5.3 eV, which suggests that Bi exists in the chemical state of Bi3+ in both BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10.

Figure 4.

XPS survey spectra (a) and high-resolution XPS spectra for Bi 4f (b) of samples B-RT, B-450 and B-600, and the variation of Bi/Cl molar ratio as a function of reaction temperature (c). The blue and red dash lines are the theoretical values of Bi/Cl molar ratio for pure BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10, respectively.

The chemical compositions of Bi, Cl and O in various samples as well as the variation of Bi/Cl molar ratio as a function of annealing temperature are displayed in Fig. 4c and Table S1. As shown in Fig. 4c, there exists a monotonic increase of Bi/Cl molar ratio with an increase of annealing temperature. When the temperature increases to 600 °C, the Bi/Cl molar ratio reaches 2.295, which is very close to the theoretical value 2.4 of Bi24O31Cl10. This observation indicates the phase transformation from pure BiOCl to Bi24O31 Cl10. It could be possibly accepted that if the Bi/Cl molar ratio is larger than the theoretical value of BiOCl, the phase transformation occurs. Thus, 450 °C could be recognized as the initial phase transformation temperature in our experiment, which is consistent with the XRD result.

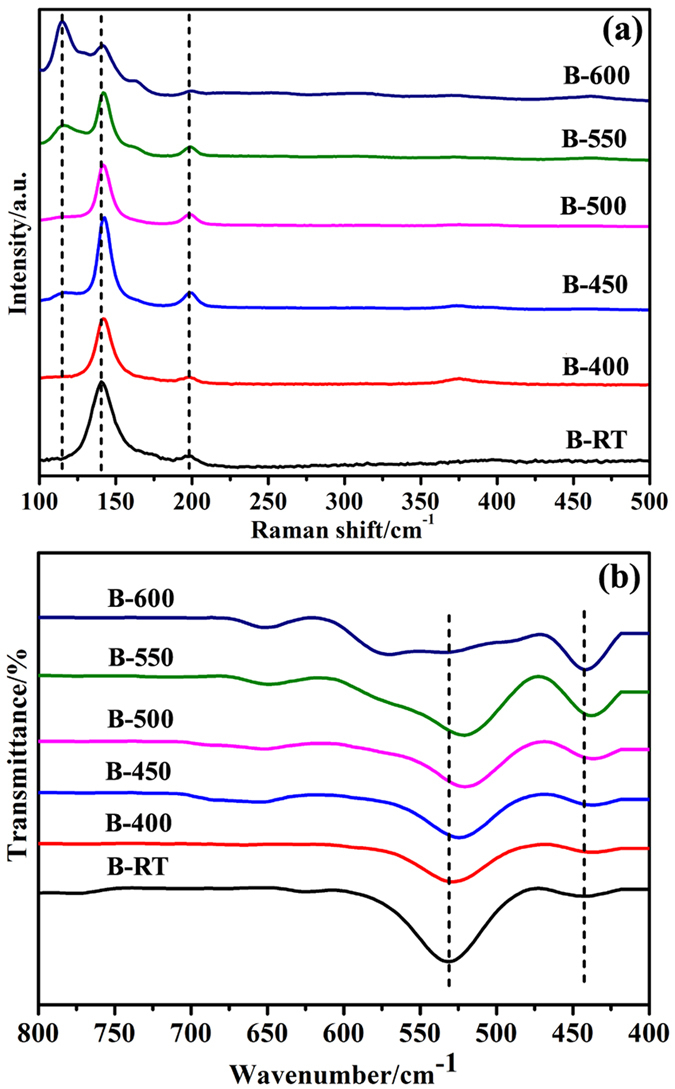

Raman and FT-IR measurements are performed to investigate the BiOCl phase transformation and interfacial interactions between BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10. For sample B-RT (Fig. 5a), there are two distinguishable Raman active bands at 140 cm−1 and 198 cm−1 which are assigned to the A1g and Eg internal Bi-Cl stretching modes47,48, respectively. However, the band related to the motion of oxygen atoms at about 400 cm−1 36,49 is very weak and nearly unnoticeable. With an increase of annealing temperature, the Raman peak assigned to A1g shifts to higher wavenumbers. This phenomenon could be ascribed to the formation of heterojunction between BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10, because the interfacial contact might produce intrinsic stresses on the crystal structure and alter the periodicity of the lattice37,50. However, for sample B-600, there exists a new band located at 115 cm−1, which is close to that of pure Bi24O31Cl10 (Figure S4)33, suggesting the presence of Bi24O31Cl10 in sample B-600.

Figure 5.

Raman spectra (a) and FT-IR spectra (b) of various samples.

Figures 5b and S5 show the FT-IR spectra of samples B-RT ~ B-600. For sample B-RT, the peaks at 3437 cm−1 and 1622 cm−1 in Figure S5 are assigned to the stretching vibration and deformation vibration of the hydroxyl group (−OH) acquired from the wet atmosphere51. The band at 2925 cm−1 represents the C-H stretching vibration52, which originates from glycerol in the synthetic procedure of BiOCl. The bands striding over the wavenumbers 1036 to 1406 cm−1 are ascribed to the stretching vibration of the C-O-C bond in glycerol52. The bands located between 200 ~ 800 cm−1 correspond to the characteristic of Bi-O bond, and the peak at about 523 cm−1 resulted from the symmetrical stretching vibration of the Bi-O band is a typical peak of BiOCl51,53,54. With an increase of the annealing temperature, the weakening of the bands assigned to −OH, C-H and C-O-C is attributed to the gradual removal of adsorbed water and glycerol (Figure S5). Furthermore, it can be identified in Fig. 5b that the band at 523 cm−1 exhibits a blue shift and the peak located at 442 cm−1 is gradually distinguishable, verifying the interfacial interactions caused by the construction of the heterojunction between BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10 as well as the dominant existence of Bi24O31Cl10, which result is similar to that of BiVO4/Bi4V2O1137. Based on the results from HRTEM, XPS, Raman and FT-IR spectra, it could be concluded that the Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction is successfully constructed, which is probably helpful for the transfer and separation of photogenerated charge carriers as well as the improvement of photocatalytic activity.

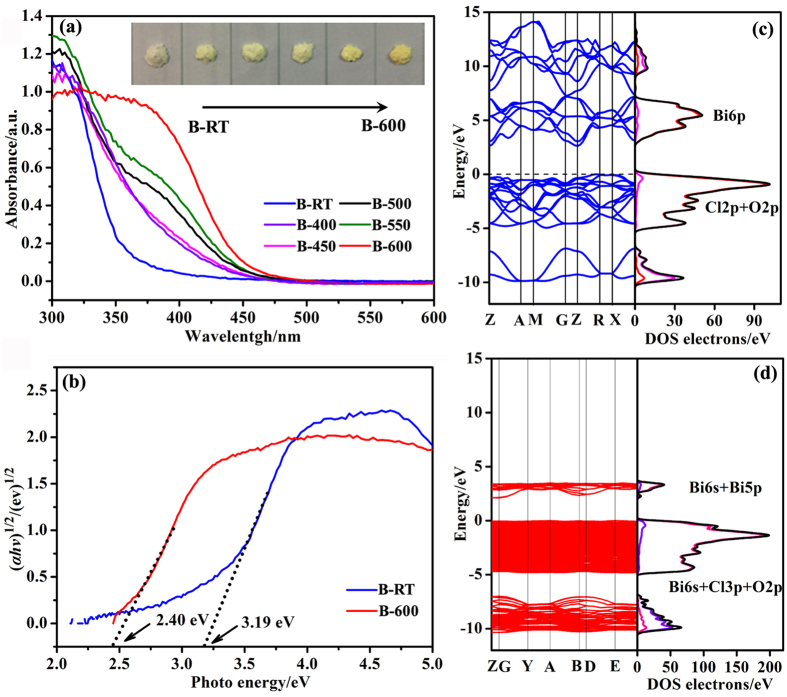

The photocatalytic performance of catalysts is related to the light absorption, thus the UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (DRS) was adopted to determine the visible light harvesting ability of BiOCl and calcined samples (Fig. 6a). BiOCl presents almost no absorption in the visible light region with an absorption edge at 360 nm. Interestingly, there exists a red shift of the absorption edge with an increase of the annealing temperature, and the sample B-600 (pure Bi24O31Cl10) possesses the most intense visible light harvesting ability with an absorption edge at about 455 nm. It should be noted that samples B-500 and B-550 exhibit similar absorption feature in comparison with pure Bi24O31Cl10 (B-600), this result is in accordance with the XRD result that massive Bi24O31Cl10 phase exists in sample B-500. The new emerged absorption edge also indicates that Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction photocatalyst should display visible light photocatalytic activity. The UV-vis spectra result is also confirmed by the colors of BiOCl (B-RT) and calcined samples (B-400 ~B-600), changing from white to yellow, as shown in inserted graph in Fig. 6a.

Figure 6.

UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) (a) and plots of (αhv)1/2 vs. the photo energy (hv) (b) for samples, calculated band structure and density of states (DOS) of BiOCl (c) and Bi24O31Cl10 (d).

It is accepted that the band gap energy of a semiconductor can be evaluated by the following equation:

|

where α, v, Eg, and A are the absorption coefficient, light frequency, band gap energy, and a constant, respectively. The parameter n is determined by the characteristics of the transition in a semiconductor (i.e., n = 1 for direct transition or n = 4 for indirect transition). In order to specify the n values of BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10, the density functional theory (DFT) calculations are carried out (Fig. 6c,d). The calculated Fermi level is set at an energy of zero eV in the band gap, indicating typical intrinsic semiconducting characteristics in the electronic structure. Fig. 6c (left) shows that the conduction band minimum (CBM) and the valence band maximum (VBM) are located at Z and R point, respectively. It indicates that BiOCl is an indirect band gap semiconductor with a band gap of 2.63 eV, which is close to the previous DFT calculations55,56. The calculated band structure and density of states (DOS) (Fig. 6c right) imply that the CB of BiOCl mainly consists of Bi6p orbitals, whereas the VB is contributed by hybridized Cl2p and O2p orbitals. It could be inferred from Fig. 6d that Bi24O31Cl10 is also an indirect band gap semiconductor with a band gap of 2.11 eV, which is consistent with the previous DFT calculations39. The CB of Bi24O31Cl10 mainly consists of Bi6s and Bi5p orbitals, whereas the VB has major contribution from the hybridized Bi6s, Cl3p and O2p orbitals.

Having these results in mind, the n values for both BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10 are 4. Thus, the band gap energies of pure BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10 could be estimated from a plot of (αhv)1/2 versus the photon energy (hv). The intercept of the tangent to the x-axis will give a good approximation of the band gap energies for various samples. As shown in Fig. 6b, the optical band gaps of sample B-RT and B-600 are calculated to be 3.19 eV and 2.40 eV, respectively, which are close to the previously reported values33,40,57.

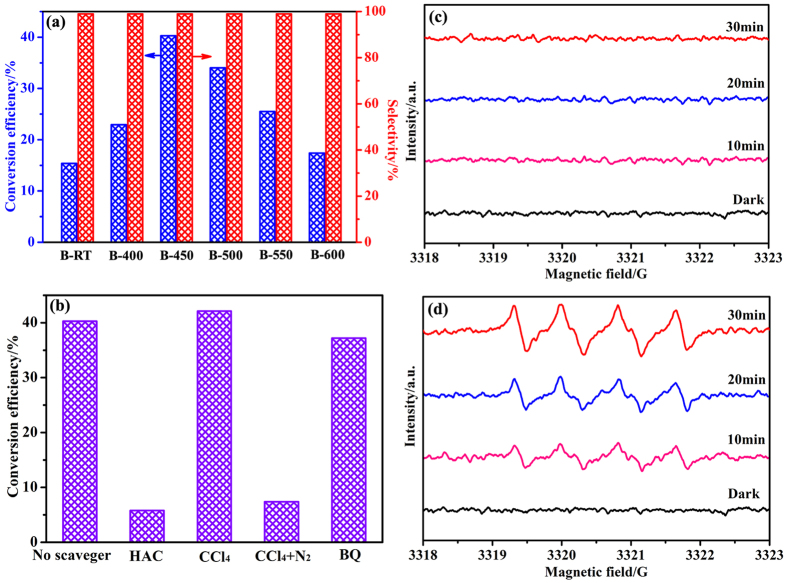

It is accepted that the selective photocatalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde using O2 as the oxidizing agent is considered as a model reaction to evaluate the photocatalytic performance of semiconductors58. Figure 7a displays the benzyl alcohol conversion efficiency over various samples. Notably, all samples exhibit photocatalytic activities toward benzyl alcohol oxidation under visible light irradiation. It’s noted that pure BiOCl (B-RT) with a band gap of 3.19 eV also shows a benzyl alcohol conversion efficiency of 15.4%. TiO2, as a wide band-gap semiconductor, also displays excellent conversion efficiency (>99%) and selectivity (>99%) toward benzyl alcohol oxidation under visible light irradiation. This phenomenon is ascribed to the corresponding absorption edge shifts and absorption intensity enhancement in the visible-light region, which is related to the formation of a visible-light responsive charge-transfer complex between TiO2 and benzyl alcohol18,19. To specify the reason that BiOCl exhibits visible light photocatalytic activity toward benzyl alcohol oxidation, UV-vis absorption spectra of benzyl alcohol (BA)-adsorbed samples are investigated (Figure S6). As illustrated in Figure S6, there is nearly no obvious changes in absorption edges and intensities in visible-light region for both BA-adsorbed samples and bare samples. Thus, it is expected that the benzyl alcohol conversion efficiency over the present samples may be not related to the charge-transfer complex formed between photocatalysts and benzyl alcohol. The photocatalytic activity of BiOCl under visible light irradiation may be related to the special nanosheet structure and  vacancy associates in BiOCl23,59. The conversion efficiency reaches a maximum of approximately 40.3% with increasing the annealing temperature to 450 °C, however, further increase of the annealing temperature leads to an obvious decrease in the conversion efficiency. Furthermore, all samples display >99% selectivity toward benzaldehyde. Although the photocatalytic performance of the as-prepared Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction is lower than that of TiO2 and NaxTaOy·nH2O1,19, it is close to even higher than several oxyhalides, such as Bi3O4Br, BiOBr and Bi12O17Cl27 (Table S2), suggesting comprehensive work needs to be further conducted for oxyhalide semiconductors in the future.

vacancy associates in BiOCl23,59. The conversion efficiency reaches a maximum of approximately 40.3% with increasing the annealing temperature to 450 °C, however, further increase of the annealing temperature leads to an obvious decrease in the conversion efficiency. Furthermore, all samples display >99% selectivity toward benzaldehyde. Although the photocatalytic performance of the as-prepared Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction is lower than that of TiO2 and NaxTaOy·nH2O1,19, it is close to even higher than several oxyhalides, such as Bi3O4Br, BiOBr and Bi12O17Cl27 (Table S2), suggesting comprehensive work needs to be further conducted for oxyhalide semiconductors in the future.

Figure 7.

Photocatalytic conversion of benzyl alcohol over various samples under visible light irradiation (a), effects of scavengers on the conversion of benzyl alcohol (b), DMPO spin-trapping ESR spectra of sample B-450 in methanol dispersion for DMPO-·OH (c) and in 20% methanol +80% methylbenzene dispersion for DMPO-·O2− (d).

It is well known that the photocatalytic process involves the photogenerated electrons and holes, which could react with the molecular O2 and H2O/HO− to yield superoxide radical (·O2−) and ·OH, respectively. The new produced active species are essentially important in the catalytic reactions. To reveal the origin of the highly photocatalytic performance and selectivity for the Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction, a series of active species trapping experiments were further conducted and the results are displayed in Fig. 7b. When acetic acid (HAC) as holes scavenger is added, the conversion efficiency of benzyl alcohol decreases significantly. The addition of tetrachloromethane (CCl4) and benzoquinone (BQ) used as an electron and superoxide radical scavenger respectively, makes a slight influence in the conversion efficiency. These observations suggest that photogenerated holes act as the dominant role in the photocatalytic conversion of benzyl alcohol. Moreover, if molecular nitrogen is used instead of molecular O2 in the presence of CCl4 during the photocatalytic process, the conversion efficiency surprisingly decreases, which suggests that molecular O2 is specially vital in the photocatalytic reaction. That is to say, the generation of superoxide radicals, which consumes lots of the photogenerated electrons, could greatly inhibit the recombination of photogenerated charge carriers, favoring the selective oxidation of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde originated by photogenerated holes.

The above result could also be proved by ESR technique. DMPO spin-trapping ESR spectra of sample B-450 to reveal the generation of active species ·O2− and ·OH are displayed in Fig. 7c and d. As shown in Fig. 7c, no characteristic ESR signal is detected either in the dark or in the visible light irradiation from 10 min to 30 min, indicating that ·OH is not involved in the photocatalytic process. In Fig. 7d, there is no characteristic ESR signal observed in dark. However, the characteristic peaks of DMPO-·O2− adduct are detected after 10 min of visible light irradiation. Furthermore, the intensity of the DMPO-·O2− signals increases with prolonging the irradiation time.

Combining the results of scavengers experiment and ESR spectra, it could be concluded that the photogenerated holes are the major active species in the photocatalytic conversion of benzyl alcohol under visible light irradiation, the active species ·O2− are indeed formed during the photocatalytic process but not involved in the photocatalytic reaction. For potential applications, the stability of the heterojunction photocatalyst should be taken into consideration. Figure S7 presents the XRD patterns of sample B-450 before and after photocatalytic process. There is no structural variation between the samples before and after catalytic reaction, indicating the strong structural stability of Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction.

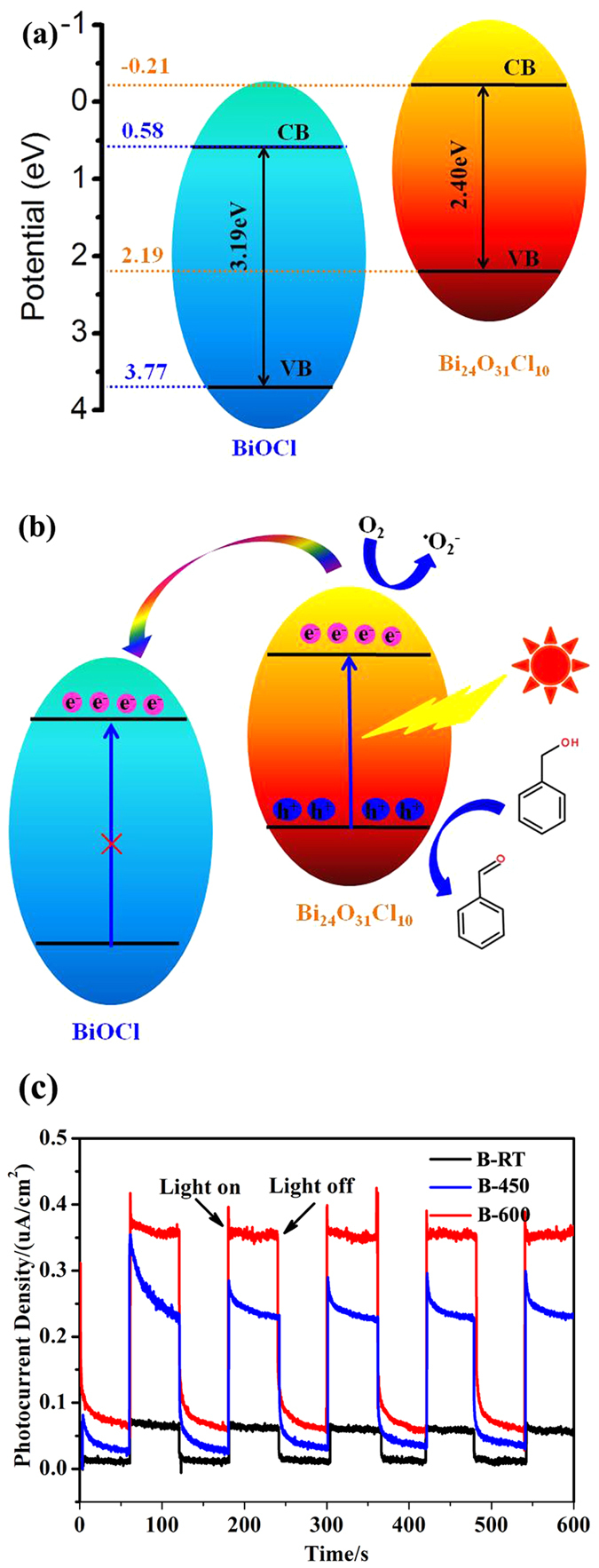

To investigate the photocatalytic process in detail, the relative conduction band (CB) and valence band (CB) potentials of the semiconductors should be determined. The Mott-Schottky plots of B-RT (BiOCl) and B-600 (Bi24O31Cl10) are shown in Figure S8. It is found that the flat-band potential (Vfb) of BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10 are determined to be 0.46 and −0.33 V versus Ag/AgCl (equivalent to 0.68 and −0.11 V versus NHE) through extrapolating the linear parts of the Mott-Schottky plots to potential axis, respectively. It is generally known that the conduction band potentials (ECB) of n-type semiconductors are very close to (0.1 ~ 0.2 eV more negative) the flat-band potentials60. Thus, we could deduce that the CB position of Bi24O31Cl10 (−0.21 eV) is more negative than that of BiOCl (0.58 eV). The schematic band diagrams of pure BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10 are illustrated in Fig. 8a.

Figure 8.

The schematic band diagrams of pure BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10 (a), the possible charge transfer of photogenerated electron-hole pairs (b) and the transient photocurrent response of samples B-RT, B-450 and B-600.

The charge transfer in the Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction is depicted in Fig. 8b. The electrons are excited from VB of Bi24O31Cl10 to the CB potential position (−0.21 eV) under visible light irradiation, but the electrons in the VB of BiOCl could not be excited because of its wide band gap. Partial photogenerated electrons transfer to the CB of BiOCl and the other part would be trapped by O2 to produce O2− radicals because of the less redox potential (−0.16 eV)61 of O2/•O2−. The photogenerated holes in the VB of Bi24O31Cl10 react with benzyl alcohol and convert them to benzaldehyde. The generation of O2− radicals greatly inhibits the recombination of photogenerated charge carriers, which is favorable for the photocatalytic performance.

To confirm the efficient separation of photogenerated charge carriers, photocurrent transient response measurements of sample B-RT, B-450 and B-600 are performed (Fig. 8c). As shown in Fig. 8c, all samples are prompt in producing photocurrent with a reproducible response to on/off cycle under visible light irradiation, suggesting that absorption of light could produce the photo-induced charge carriers and the charge carriers could transfer effectively. In comparison with B-RT and B-600, the sample B-450 displays the strongest peak intensity, implying more excellent photocatalytic activity of the Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction than the sole semiconductor counterparts.

Conclusions

A Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction has been successfully constructed through a simple thermal annealing route. Various characterization techniques confirm the construction of the Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction during the annealing process. The obtained Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl photocatalyst displays excellent photocatalytic efficiency and selectivity toward the conversion of benzyl alcohol to benzaldehyde under visible light irradiation, which could reach 40.3% and >99%, respectively. The photogenerated holes play an important role in the photocatalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol and superoxide radicals are not involved in the photocatalytic process. The in-situ generation of heterojunction photocatalysts may provide superior interfacial contact, which is advantageous for enhancing the photocatalytic performance.

Methods

Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction synthesis

All chemical solvents and reagents were analytical grade and were used without further purification. In a typical procedure, 0.776 g Bi(NO3)3·5H2O was dissolved in 76 mL of glycerol, denoted as solution A. Then, 0.12 g KCl was dissolved in 4 mL of deionized water (solution B), which was subsequently poured into solution A. After stirring for 15 min, the mixture was transferred into a 100 mL Teflon-lined stainless steel autoclave, heated to 110 °C and kept at this temperature for 8 h. The resulting precipitate was collected by centrifugation, then washed with ethanol and deionized water for several times, and dried at 80 °C in vacuum to obtain the pure BiOCl powder (denoted as B-RT).

The thermal annealing step was performed in an air-atmosphere programmable tube furnace in the temperature range of 400 ~ 600 °C with an interval of 50 °C. The final products were denoted as B-400 ~B-600, respectively.

Characterization

Detailed crystallographic information of the synthesized samples was obtained on an X-ray diffractometer (Empypean Panalytical) with Cu Ka radiation (λ = 0.15406 nm). The thermogravinetric analysis (TG) and differential thermal analysis (DTA) were carried out on a thermal analyzer (NETZSCH STA 449F3) where the sample was heated from 30 to 950 °C with a raising ramp rate of 10 °C/min under nitrogen atmosphere. The detailed morphology, structure and heterojunction feature of the samples were recorded by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high resolution TEM (HRTEM) on a JEM-2010 apparatus with an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The surface state and chemical composition of the samples were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), which was carried out on a Thermo Escalab 250Xi with a monochromatic Al Ka (hv = 1486.6 eV). Raman spectra were recorded on the Horiba Jobin Yvon LabRAM HR800 instrument with the laser excitation of 532 nm. Fouier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) was performed using a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrophotometer using KBr powder-pressed pellets. The UV-vis absorption spectra were measured using a UV-vis spectrophotometer (Lambda 750s) in the range of 200 ~ 800 nm. The specific surface area (SBET) of the samples was obtained from N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77 K (ASAP 2020). Prior to the sorption experiment, the materials were dehydrated by evacuation under specific conditions (200°C, 10 h).

The photocurrent transient response measurement was carried out based on a lock-in amplifier. The measurement system is constructed by a sample chamber, a lock-in amplifier (SR 830, Stanford Research Systems, Inc.) with a light chopper (SR540, Stanford Research Systems, Inc.) and a source of monochromatic light which is provided by a 500 W xenon lamp (CHF-XM 500, Trusttech) and a monochromator (Omni-λ300, Zolix). The monochromator and the lock-in amplifier were equipped with a computer. The analyzed product is assembled as a sandwich-like structure of ITO-product-ITO, which ITO means an indium tin oxide electrode. All the measurements were performed in air atmosphere and at room temperature.

Electron spin resonance (ESR) spectra were obtained on a Brüker ER200-SRC apparatus. A frequency of about 9.06 GHz was used for a dual-purpose cavity operation. The magnetic field of 0.2 mT was modulated at 100 kHz. A microwave power of about 1 mW was employed. Other parameters for the apparatus were set at: sweep width of 250 mT, center field of 250 mT, sweep time of 2.0 min, and accumulated 5times. All measurements were performed at room temperature in air without vacuum-pumping. ESR spectra for hydroxyl radicals and superoxide radicals were conducted in methylbenzene solution (2.0 mL) and methylbenzene solution containing methyl alcohol (2 mL, the volume ratio of methyl alcohol being 20%), respectively. The experiments were processed in dark and under visible light irradiation with adding 4 mg sample and 0.05 M DMPO.

All calculations were performed with density functional theory (DFT), using the CASTEP program package. The kinetic energy cutoff is 420 eV, using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) to treat the models. Geometry optimization is carried out until the residual forces were smaller than 0.01 eV Å−1, and the convergence threshold for self-consistent iteration was set at 5 × 10−7 eV.

Photocatalytic activity Test

Selective Oxidation of benzyl alcohol has been widely studied as a model reaction to estimate the photocatalytic performance of catalysts. The photocatalytic activity experiments were carried out in a photochemical reactor fitted with a 500 W xenon lamp and a visible-light optical filter (λ > 420 nm). 10 mL methylbenzene solution involving alcohol (1 mM) mixed with 0.05 g sample was magnetically stirred at 25 °C in water bath. Anaerobic and aerobic reactions were performed by bubbling with pure N2 and O2, respectively, for at least 1 hour before visible-light irradiation. After illuminating 10 hours, the suspension was centrifuged to remove the powder and measured the concentration of the alcohol and product by GC-FID (Shimadzu GC-2014C).

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Liu, X. et al. Constructing Bi24O31Cl10/BiOCl heterojunction via a simple thermal annealing route for achieving enhanced photocatalytic activity and selectivity. Sci. Rep. 6, 28689; doi: 10.1038/srep28689 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC NO. 51462025) and the Inner Mongolia Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 2013MS0204).

Footnotes

Author Contributions C.D. conceived the project, analyzed the data and wrote the final paper. X.L. synthesized and characterized the samples. Y.S. characterized the samples and analyzed the data. Q.Z. designed the experiments. Z.L. and C.D. discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Su Y., Lang J., Du C., Bian F. & Wang X. Achieving exceptional photocatalytic activity and selectivity through a well-controlled short-ordered structure: a case study of NaxTaOy·nH2O. ChemCatChem 7, 2437–2441 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Mueller J. A., Goller C. P. & Sigman M. S. Elucidating the significance of β-hydride elimination and the dynamic role of acid/base chemistry in a palladium-catalyzed aerobic oxidation of alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 9724–9734 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallat T. & Baiker A. Oxidation of alcohols with molecular oxygen on solid catalysts. Chem. Rev. 104, 3037–3058 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallett-Tapley G. L. et al. Plasmon-mediated catalytic oxidation of sec-phenethyl and benzyl alcohols. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 10784–10790 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Conte M., Miyamura H., Kobayashi S. & Chechik V. Spin trapping of Au-H intermediate in the alcohol oxidation by supported and unsupported gold catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 7189–7196 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsudome T., Noujima A., Mizugaki T., Jitsukawa K. & Kaneda K. Efficient aerobic oxidation of alcohols using a hydrotalcite-supported gold nanoparticle catalyst. Adv. Synth. Catal. 351, 1890–1896 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Xiao X., Jiang J. & Zhang L. Selective oxidation of benzy alcohol into benzaldehyde over semiconductors under visible light: the case of Bi12O17Cl2 nanobelts. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 142–143, 487–493 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Hajimohammadi M., Safari N., Mofakham H. & Deyhimi F. Highly selective, economical and efficient oxidation of alcohols to alhehydes and ketones by air and sunlight or visible light in the presence of porphyrins sensitizers. Green Chem. 13, 991–997 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto D. et al. Gold nanoparticles located at the interface of anatase/rutile TiO2 particles as active plasmonic photocatalysts for aerobic oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 6309–6315 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa S., Tamura A., Shishido T., Teramura K. & Tanaka T. Solvent-free aerobic alcohol oxidation using Cu/Nb2O5: green and highly selective photocatalytic system. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 110, 216–220 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Li C. J., Xu G. R., Zhang B. & Gong J. R. High selectivity in visible-light-driven partial photocatalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol into benzldehyde over single-crystalline rutile TiO2 nanorods. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 115–116, 201–208 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Paszkiewicz M., Luczak J., Lisowski W., Patyk P. & Zaleska-Medynska A. The ILs-assisted solvothermal synthesis of TiO2 spheres: the effect of ionic liquids on morphology and photoactivity of TiO2. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 184, 223–237 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. et al. Improved catalytic capability of mesoporous TiO2 microspheres and photodecomposition of toluene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2, 3134–3140 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo C. et al. Directed synthesis of mesoporous TiO2 microspheres: catalysts and their photocatalysis for bisphenol A degradation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 419–425 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. et al. Anodic formation of thick anatase TiO2 mesosponge layers for high-efficiency photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1487–1479 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Yang G., Lyu W. & Yan W. Thorny TiO2 nanofibers: synthesis, enhanced photocatalytic activity and supercapacitance. J. Alloys Compd. 659, 138–145 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury B., Bayan S., Choudhury A. & Chakraborty P. Narrowing of band gap and effective charge carrier separation in oxygen deficient TiO2 nanotubes with improved visible light photocatalytic activity. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 465, 1–10 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C. J., Xu G. R., Zhang B. & Gong J. R. High selectivity in visible-light-driven partial photocatalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol into benzaldehyde over single-crystalline rutile TiO2 nanorods. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 115–116, 201–208 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Higashimoto S. et al. Selective photocatalytic oxidation of benzyl alcohol and its derivatives into corresponding aldehydes by molecular oxygen on titanium dioxide under visible light irradiation. J. Catal. 266, 279–258 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X., Ai Z. H., Jia F. L. & Zhang L. Z. Generalized one-pot synthesis, characterization, and photocatalytic activity of hierarchical BiOX (X = Cl, Br, I) nanoplate microspheres. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 747–753 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Liu L. & Zhou Z. First-principles studies on facet-dependent photocatalytic properties of bismuth oxyhalides. RSC Adv. 2, 9224–9229 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Gnayem H. & Sasson Y. Hierarchical nanostructured 3D flowerlike BiOClxBr1−x semiconductors with exceptional visible light photocatalytic activity. ACS Catal. 3, 186–191 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Sun M., Zhao Q., Du C. & Liu Z. Enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity in BiOCl/SnO2: heterojunction of two wide band-gap semiconductors. RSC Adv. 5, 22740–22752 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Chen G., Fang G. L. & Tang G. D. Photoluminescence and photocatalytic properties of BiOCl and Bi24O31Cl10 nanostructures synthesized by electrolytic corrosion of metal Bi. Mater. Res. Bull. 48, 1256–1261 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Xian Z. & Jun Y. Exploring the effects of nanocrystal facet orientations in g-C3N4/BiOCl heterostructures on photocatalytic performance. Nanoscale 7, 18971–18983 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S. et al. In situ synthesis of hierarchical flower-like Bi2S3/BiOCl composite with enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity. Appl. Surf. Sci. 290, 313–319 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Dong F., Sun Y., Fu M. Z., Wu S. & Lee C. Room temperature synthesis and highly enhanced visible light photocatalytic activity of porous BiOI/BiOCl composites nanoplates microflowers. J. Hazard. Mater. 219–220, 26–34 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B. et al. Efficient visible light photocatalytic activity of CdS on (001) facets exposed to BiOCl. New J. Chem. 38, 2273–2277 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Shamaila S., Sajjad A. K. L., Chen F. & Zhang J. WO3/BiOCl, a novel heterojunction as visible light photocatalyst. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 356, 465–472 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z. et al. BiOCl/BiVO4 p-n heterojunction with enhanced photocatalytic activity under visible-light irradiation. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 389–398 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Chang X. et al. Enhancement of photocatalytic activity over NaBiO3/BiOCl composite prepared by an in situ formation strategy. Catal. Today 153, 193–199 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Li L. P., Su Y. G. & Li G. S. Size-induced symmetric enhancement and its relevance to photoluminescence of scheelite CaWO4 nanocrystals. AppL. Phys. Lett. 90, 054105–3 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Jin X. et al. Bismuth-rich strategy induced photocatalytic molecular oxygen activation properties of bismuth oxyhalogen: the case of Bi24O31Cl10. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 165, 668–675 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Wei W., Dai Y. & Huang B. First principle characterization of Bi-based photocatalysts: Bi12TiO20, Bi2Ti2O7 and Bi4Ti3O12. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 5658–5663 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Zhang L. Z., Li Y. J. & Yu Y. Synthesis and internal electric field dependent photoreactivity of Bi3O4Cl single-crystalline nanosheets with high {001} facet exposure percentages. Nanoscale 6, 167–171 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myung Y. et al. Highly conducting, n-type Bi12O16Cl6 nanosheets with superlattice-like structure. Chem. Mater. 27, 7710–7718 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Lv C. et al. Realizing nanosized interfacial contact via constructing BiVO4/Bi4O2O11 element-copied heterojunction nanofibers for superior photocatalytic properties. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 179, 54–60 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Eggenweiler U., Keller E. & Krämer V. Redetermination of the crystal structure of the ‘Arppe compound’ Bi24O31Cl10 and the isomorphous Bi24O31Br10. Acta Crystallographica Section B B56, 431–437 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L. et al. A dye-sensitized visible light photocatalyst-Bi24O31Cl10. Sci. Rep. 4, 1–8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F. T. et al. In-situ one-step synthesis of novel BiOCl/Bi24O31Cl10 heterojuncitons via self-combustion of ionic liquid with enchanced visible-light photocatalytic activities. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 150–151, 574–584 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G., Xiong J. & Stadler F. J. Facile template-free and fast refluxing synthesis of 3D desertrose-like BiOCl nanoarchitectures with superior photocatalytic activity. New. J. Chem. 37, 3207–3213 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Yu J., Xiang Q. & Zhou M. Preparation, characterization and visible-light-driven photocatalytic activity of Fe-doped titania nanorods and first-principles study for electronic structures. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 90, 595–602 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Moulder J. F., Stickle W. F., Sobol P. E. & Bomben K. D. Handbook of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy physical electronics division, Perkin-Elmer Corporation, Eden Prairie, MN, USA, (1992).

- He Y. et al. Z-scheme SnO2−x/g-C3N4 composite as an efficient photocatalyst for dye degradation and photocatalytic CO2 reduction. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. C. 137, 175–184 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Liu G. & Jaegermann W. XPS and UPS characterization of the TiO2/ZnPcGly heterointerface: alignment of energy levels. J. Phys. Chem. B 106, 5814–5819 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Li X. H. et al. Local chemical states and thermal stabilities of nitrogen dopants in ZnO film studied by temperature-dependent X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 191903–191903-3 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Fan W. Q. et al. Fabrication of TiO2-BiOCl double-layer nanostructure arrays for photoelectrochemical water splitting. CrystEngComm 16, 820–825 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Weng S., Chen B., Xie L., Zheng Z. & Liu P. Facile in situ synthesis of Bi/BiOCl nanocomposite with high photocatalytic activity. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 3068–3075 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Xu S., Wang S., Zhang Y. & Li G. Citric acid modulated electrochemical synthesis and photocatalytic behavior of BiOCl nanoplates with exposed {001} facets. Dalton Trans. 43, 479–485 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G. P. et al. Core-level photoemission measurements of valence-band offsets in highly strained heterojunctions: Si-Ge system. Phys. Rev. B 39, 1235–1241 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie T., Xu L., Liu C., Yang J. & Wang M. Magnetic composite BiOCl-SrFe12O19: a novel p-n type heterojunction with enhanced photocatalytic activity. Dalton Trans. 43, 2211–2220 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G., Xiong J. & Stadler F. J. Facile template-free and fast refluxing synthesis of 3D desertrose-like nanoarchitectures with superior photocatalytic activity. New J. Chem. 37, 3207–3213 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Fruth V., Popa M., Berger D., Ionica C. M. & Jitianu M. Phase investigation in the antimony doped Bi2O3 system. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 24, 1295–1299 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Song J., Mao C., Niu H., Shen Y. & Zhang S. Hierarchical structured bismuth oxychlorides: self-assembly from nanoplates to nanoflowers via a solvothermal route and their photocatalytic properties. CrystEngComm 12, 3875–3881 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Yang W., Wen Y., Chen R., Zeng D. & Shan B. Study of structural , electronic and optical properties of tungsten doped bismuth oxychloride by DFT calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 21349–21355 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L. P. et al. Self-assembled 3D BiOCl hierarchitectures: tunable synthesis and characterization, CrystEngComm 12, 3791–3796 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Wang D. H. et al. Nanosheet-constructed porous BiOCl with Dominant {001} Facets for Superior Photosensitized Degradation. Nanoscale 4, 7780–7785 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. H. & Xu Y. J. Bi2WO6: a highly chemoselective visible light photocatalyst toward aerobic oxidation of benzylic alcohols in water. RSC Adv. 4, 2904–2910 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Guan M. et al. Vacancy associates promoting solar-driven photocatalytic activity of ultrathin bismuth oxychoride nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10411–10417 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M. et al. Efficient degradation of azo dyes over Sb2S3/TiO2 heterojunction under visible light irradiation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 51, 2897–2903 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- He W. et al. Production of reactive oxygen species and electrons from photoexcited ZnO and ZnS nanoparticles: a comparative study for unraveling their distinct photocatalytic activies. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 3187–3195 (2016). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.