1.0 Introduction

Prescription opiate dependence is a serious problem in the United States, with approximately 1.9 million people suffering from substance use disorders associated with opioid analgesics (SAMHSA, 2013). Treatment admissions for the primary abuse of opiates other than heroin have increased from one percent of all admissions in 1997, to 10 percent in 2012 (SAMHSA, 2014). In addition, there is growing evidence that a relationship exists between prescription opiate dependence and subsequent heroin abuse, further exacerbating the opioid epidemic (SAMHSA, 2013). Prescription opiate dependence, like dependence on other drugs of abuse, is a disorder of chronic relapse; as such, there is a pressing need to address factors that identify and attenuate the risk of relapse (O'Brien et al., 1998; Tkacz et al., 2012). The primary purpose of the current study was to investigate the relationship between a relatively understudied construct, low positive affect (PA), and craving in a sample of prescription opiate dependent patients in residential treatment. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) data were used to predict craving from both person-levels and day-levels of PA, as well as their interaction. The associations between negative affect (NA) and craving were also examined to evaluate potential differences in the relationship of NA to craving relative to PA, as well as to ensure that the results for PA and craving were independent of levels of NA.

Deficits in the experience and expression of emotion have been linked to substance use disorders (SUDs) even in the absence of affective psychopathology, emphasizing the need to better understand the role of affect in SUDs (Cheetham et al., 2010; Goldstein & Volkow, 2011). Such research may help clarify how risk is conferred, and how addictive behaviors are maintained, thereby facilitating better treatments and attenuating relapse (Cheetham et al., 2010). Dysregulated affect, including anhedonia, irritability, anxiety, and dysphoric mood, as well as increased reactivity to stress and craving, are common symptoms of the abstinence symptomatology observed in post-withdrawal state from opiates (Koob & LeMoal, 2001; Martin, Jasinski, Haertzen et al., 1973). Similar abstinence symptomatology has been described in alcohol, cocaine, cannabis, stimulants, (Bovasso, 2001; Gawin & Ellinwood, 1988; Gawin & Kleber, 1986; Heinz, et al., 1994; Miller et al., 1993), and polysubstance abuse (Martinotti et al., 2009). These symptoms are thought to increase vulnerability to relapse in the early stages of abstinence and beyond, into the phase of protracted withdrawal (Heilig et al., 2010). Little is known, however, about the role of low PA as it relates to craving and relapse in the early stages of prescription opiate dependence. This lack of knowledge stems from fewer studies that evaluate the role of low PA as it contributes to craving and relapse in early abstinence, relative to studies that examine the role of NA (Cheetham et al., 2010).

One reason that low PA may have been overlooked is that many investigators (tacitly) ascribe to a circumplex model of affective space; within this model PA and NA are conceptualized as opposite ends of a continuum, rather than as independent neural systems with separate neurophysiological underpinnings (Ameringer & Leventhal, 2010; Bujarski, et al., 2015). As such, many investigators focus on NA and stress response systems to the exclusion of the PA system. Indeed, NA, or dysphoria, is regularly cited as a persistent symptom of withdrawal from opiates that contributes to risk of relapse (Nestler, 2001; De Vries & Shippenberg, 2002; Epstein et al., 2009; Moore et al., 2013). However, there is considerable evidence that NA and PA are indeed relatively independent, and may function together or independently (Cacioppo & Berntson, 1994; Cacioppo et al., 1999; Norman et al., 2011).

Recent research suggests that low PA, independent of NA, may be associated with increased craving, putting patients at greater risk for relapse. A recent study using inventory measures of affect and craving found that PA moderated the association between stress and NA such that individuals with higher levels of PA exhibited a weaker associations between stress and NA in treatment-seeking alcohol-dependent outpatients (McHugh et al., 2013). Importantly, however, PA was negatively associated with alcohol craving. Short term increases in PA have also been associated with a decreased risk for smoking lapse, suggesting PA may play a protective role in early nicotine abstinence (Ferguson, Shiffman, & Gwaltney, 2006). Bujarski et al (2015) also found that PA was negatively correlated with craving, whereas the level of withdrawal/NA was positively associated with craving. However, the temporal dynamics were different, demonstrating the independent role of PA in nicotine abstinence over and above that of NA.

Similar results have been found with regards to a related construct, anhedonia. Defined as the impaired capacity to experience pleasure, or the inability to experience pleasure in response to rewarding stimuli (Snaith, 1993), anhedonia can be conceptualized as either a state symptom or a personality trait. As a trait, anhedonia varies widely in the population, lies on a continuum, and can be distinguished psychometrically from similar constructs such as sadness, flattened affect, and amotivation (Leventhal et al. 2006; Loas et al. 2009; Loas et al. 1994). Anhedonia has frequently been described in substance dependent populations, especially as part of the abstinence symptomatology (Hatzigiakoumis et al., 2011). Although it plays a critical role in theoretical models of relapse (e.g., Koob & Le Moal, 2001; Volkow et al., 2002), several investigators describe anhedonia as underrepresented in the literature (Garfield et al., 2014; Hatzigiakoumis et al., 2011; Martinotti et al., 2012; Sussman & Leventhal, 2014). Consistent with the findings with regard to low PA, Janiri and colleagues (2005) demonstrated that craving was positively associated with anhedonia levels in an opiate-dependent patient population, whereas craving was negatively associated with hedonic capability. Anhedonia has also been shown to have a positive correlation with craving in recently withdrawn alcohol-dependent (Martinotti et al., 2008a, 2008b), opioid-dependent patients (Martinotti et al., 2008a), and recently abstinent tobacco smokers (Cook et al., 2004; Leventhal et al., 2009). Although low PA and anhedonia are empirically related when each is measured with a trait-style questionnaire (Pearson’s correlations ranging from .20–.43; Cook, Spring, & McChargue, 2007; Franken, Rassin, & Muris, 2007; Leventhal et al., 2009), they are not identical constructs (Ameringer & Leventhal, 2010). Whereas an individual with low PA may have a sustained period of boredom, disinterest, and attenuated pleasure, they are able to experience pleasure in response to a rewarding stimulus should they encounter one in their environment. The anhedonic individual, in contrast, does not experience pleasure or experiences significantly attenuated pleasure in response to putatively rewarding stimuli. Whereas there may be overlap between these two constructs, there is good reason to study low PA versus the trait of anhedonia.

The current study investigated associations between daily levels of craving – perhaps the most proximate intrapersonal state trigger for relapse – and both the person-level and day-level means of PA and NA. This level of analysis was motivated, in part, by the observation that individuals have been shown to have difficulty accurately evaluating the intensity of their own emotional ratings across time (Fredrickson & Kahneman, 1993; Kahneman et al., 1993; Redelmeier & Kahneman, 1996). Research suggests that retrospective evaluations of affective experiences appear to be determined by a weighted average of the actual affective experiences. For example, Thomas and Diener (1990) have shown that, when asked to recall emotional intensity across a time span (e.g., 3–6 weeks), people tend to overestimate their emotional intensity relative to their actual daily ratings, and underestimate the frequency of their positive affect vs. their negative affect. Consequently, trait ratings of emotional intensity (e.g., like those used in questionnaire measures of anhedonia), are more likely to reflect the influence of the individual’s overall conceptualization of who they think they are, rather than their actual daily experiences of mood (Pennebaker, 2000). Whereas trait ratings have important predictive validity, accurate assessment of mood states are expected to provide additional insights into the relationship between low PA, NA and craving.

EMA serves as a more accurate method for participants to report their subjective experiences (Freedman et al., 2006). During EMA, participants take a brief survey several times a day to capture total mood, diurnal changes in mood, and changes in mood over an extended period of time. The use of EMA provides a robust assessment of PA that can help reduce the systematic influences stemming from participant response bias, in part by measuring the events close in time to the actual moods (Moskowitz & Young, 2006). Summing across these multiple assessments also provides increased reliability relative to single time-point or retrospective reports (Bolger et al., 2003). As such, EMA is expected to add to our understanding of the relationship between low PA and craving

Beyond EMA’s methodological capacity to increase reliability by collecting data on emotional states and experiences closer to the time when they are experienced, EMA provides data that can allow analyses to consider the within-person nature of the interrelationships between causes and effects. In the current study, analyses leveraged within-person assessments of affective states and craving to evaluate both within-day associations between craving and affect, as well as to evaluate how person-level averages (i.e., a given person’s average level) of positive and negative affect interact with day-levels (i.e., that person’s level on a given day) of these same affective states to influence daily experiences of craving. For example, if an individual typically reports low PA on a consistent basis, how do they rate their craving on days when they report lower than typical PA?

This research was designed to increase our understanding of the within-person and within-day associations between low levels of PA and drug craving early in the recovery process following withdrawal from prescription opiates. The current analyses utilized data collected from recovering prescription opiate dependent patients (PODPs) in a clinical residential setting. To examine affective influences on cravings in the early stages of recovery, we recruited recently withdrawn (RW) PODPs (10–14 days post-medically assisted withdrawal) residing in a clinical residential setting, and collected EMA data over the course of 12 days.

The within-person data provided by EMA collections allow investigation of novel research questions regarding the interplay between person-levels and day-levels of PA and NA as they contribute both directly and interactively to day-levels of reported cravings. Several hypotheses guided our investigation. Although prior research provides support for hypothesized main effects of both person-level and day level main effects of affective states on cravings, the proposed interactions between person- and day-levels as they contribute to cravings were more exploratory. Hypotheses are as follows:

-

1a

Person-level averages of PA will be negatively associated with cravings. 1b. Day-level PA will be negatively related to same-day cravings. 1c. Moreover, person-level averages of PA will moderate within-day associations between day-level PA and same-day cravings, whereby lower within-person levels of PA will be most strongly linked to cravings among participants with lower mean levels of PA.

-

2a

Person-level averages of NA will be positively associated with cravings. 2b. Day-level NA will be positive related to same-day cravings. 2c. Similar to what we expect for PA, we expect that person-level averages of NA will moderate within-day associations between day-level NA and same-day cravings, whereby higher within-person levels of NA with be most strongly linked to cravings among those participants with higher mean levels of NA.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Participants

Participants (n = 73; 30% female) were recruited at the Caron Treatment Center, a residential drug and alcohol treatment facility in Wernersville, Pennsylvania. All participants provided written informed consent after a full explanation of procedures, per the protocol endorsed by the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine Internal Review Board. Participants ranged in age from 19 to 56 (M = 29, Range = 19–56). For the present analyses, data were available for 764 total days across 73 participants, with a mean of 10.47 (SD = 3.80, Range = 1–19) days. PODPs had completed medically assisted withdrawal at Caron 10–14 days prior to the beginning of data collection (see Table 1 for demographics). Patient inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) capable and willing to comply with the research protocol; (2) met criteria for opioid dependence {Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Health Disorders – Fourth Edition – Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR; as determined by clinical staff at the Caron Foundation, the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis, DSM-IV-TR (SCID; First et al., 2002), and Form-90D (Westerberg et al., 1998)}; (3) prescription opioids were the primary drug of choice; (4) over the age of 18; and (5) staying in residential treatment for at least 30 days. Exclusion criteria included (1) any history of serious mental illness (bipolar disorder or schizophrenia) or psychosis, as diagnosed by the SCID; (2) intravenous heroin use; (3) history of traumatic brain injury; (4) current use of any opiate agonist (methadone or buprenorphine) or antagonist (Naltrexone).

Table 1.

Rotated Factor Pattern Loadings for Mood Adjectives (Promax rotation standardized regression coefficients)

| Rotated Factor Pattern Loadings | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factor1 | Factor2 | |

| Happy | 0.88 | −0.06 |

| Joyful | 0.88 | 0.04 |

| Loving | 0.88 | 0.06 |

| Affectionate | 0.88 | 0.08 |

| Warm | 0.87 | 0.07 |

| Enthusiastic | 0.87 | 0.05 |

| Relaxed | 0.73 | −0.16 |

| Calm | 0.70 | −0.18 |

| Guilty | 0.08 | 0.85 |

| Ashamed | 0.08 | 0.83 |

| Sad | 0.02 | 0.80 |

| Anxious | 0.05 | 0.79 |

| Irritable | −0.10 | 0.78 |

| Stressed | −0.08 | 0.77 |

| Angry | −0.06 | 0.76 |

| Lonely | −0.04 | 0.76 |

Note: Factor loadings that exceed 0.70 are highlighted in bold italic font.

2.2 EMA Data Collection

Participants were equipped with smart phones programmed to administer a mood/craving survey 4 times daily. For 12 consecutive days, a preset alarm notified participants to complete surveys at morning, noon, mid-afternoon and evening times that did not conflict with their treatment program. Real time data were streamed to a secure server at the University campus to monitor compliance and data quality. Surveys took approximately 2–3 minutes each to complete. Research staff also used brief, in-person meetings to build rapport, answer participant questions, and manage any technical difficulties.

2.3. Measures

Craving

Frequency of drug craving was measured four times daily as responses to the question “Since last data entry, how FREQUENT are your drug CRAVINGS?” on a 100-point touch point continuum, with anchors at “No Cravings” to “Very Frequent” (numbers were not visible to participants). Intensity of drug craving was measured four times daily as responses to the question “Since last data entry, how INTENSE are your drug CRAVINGS?” also on a 100-touch point continuum with anchors at ”No Cravings” to “Very Intense.” For morning assessments, the stem for each item took the form of “Since waking” rather than “Since last data entry”. The product of the frequency and intensity of drug craving was created for each individual at each time point, and an average daily craving score was created for each participant for each day of the study from this product. The mean level of craving reported by participants was 1542.58 (SD = 2318.68, Range = 0 to 10000).

Positive Affect

PA was measured 4 times per day using the sum of 8 items: “warmhearted”, “joyful”, “enthusiastic”, “happy”, “affectionate”, “loving”, “relaxed”, “calm”. An average daily PA score was created for each participant for each day of the study. Participants reported a mean PA level of 51.88 (SD = 18.95, Range = 0 – 99.81).

Negative Affect

NA was measured 4 times per day using the sum of 8 items: “angry”, “irritable”, “lonely”, “sad”, “guilty”, “ashamed”, “anxious”, and “stressed”. Daily NA score was created for each participant for each day of the study. Participants reported a mean level of NA of 41.01 (SD = 20.13, Range = 0 – 88.55).

2.4. EMA mood adjective factor analysis

A principal factor analysis (FA) using promax rotation was conducted to confirm the factor structure of the daily average mood items. Two eigenvalues exceeded 1.00 (both values > 4.00) and accounted for 92.78% of the standardized variance. A scree plot confirmed the presence of two factors, with a flat slope thereafter. Two factors were thus retained and a promax rotation yielded high loadings on (≥ 0.70) on both factors (see Table 1). Eight items loaded on factor 1 (labeled PA) and eight items loaded on factor 2 (labeled NA). All cross-loadings were low (≤ 0.18) and all but two were less than or equal to 0.10. The standardized Chronbach’s alphas for the two factors (PA and NA) were 0.95 and 0.93, respectively. The correlation between the factors was −0.13.

Covariates

Gender and age were obtained from an initial demographics questionnaire.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The intensive repeated measures data (764 days nested within 73 persons) were analyzed using multilevel models (Snijders & Bosker, 2012) that were parameterized to separate day-level and person-level associations between affect and craving (see Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013). Person-level variables for PA and NA were calculated as the arithmetic mean across each participant’s repeated measures and represent each participant’s average PA and average NA (i.e., their person-level means) across the study. Day-level variables were calculated as deviations from these person-level means. Age, gender, and time were sample-mean centered.

Models for the association between PA and NA and craving, as well as covariates, were constructed as

where cravingit is the reported craving for person i on day t; β0i indicates the expected level of craving on a day in the middle of the study when PA and NA are at their mean level for the typical individual; β1i and β2i indicate differences in craving associated with the day-level PA and NA variables, respectively; β3i indicates the effect of day in the study on craving in order to account for time as a third variable (see Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013); and eit are day-specific residuals that were allowed to autocorrelate (AR1). Person-specific intercepts and associations from the Level 1 model were specified at Level 2 as

where the γs are sample-level parameters and the us are residual between-person differences that may be correlated, but are uncorrelated with eit. Parameters γ01 to γ04 indicate the effects of person-level mean PA, person-level mean NA, age, and gender on craving. Parameters γ11 and γ21 indicate how between-person differences in the day-level association of day’s PA and day’s NA, respectively, with craving were moderated by person-level mean PA and person-level mean NA, respectively.

All models were fit using SAS Proc Mixed, with incomplete data treated using missing at random assumptions. Significant interactions were followed-up using the Johnson-Neyman technique (Bauer & Curran, 2005; Johnson & Neyman, 1936) using software available online (ww.quantpsy.org/interact/hlm2.htm). Statistical significance was evaluated at α= .05.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Demographics

Table 2 describes the demographics, psychiatric comorbidity, addiction history, and concurrent medication use of the participants.

Table 2.

Participant Demographic Characteristics, Comorbid Disorders, and Medications

| Mean Age (+/1 SD) | 29.0 (8.6) |

| Gender (Female) | 30.1% |

| Depressive Disorders | 57.3% |

| GAD | 36.4% |

| Alcohol Dependence | 27.2% |

| SSRI | 23.3% |

| SNRI | 5.5% |

| α-2 Adrenergic Receptor Agonist | 2.7% |

| Tetracycline | 15.1% |

Note: GAD = Generalized Anxiety Disorder; SSRI = Selective-serotonin reuptake inhibitor; SNRI = Selective-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor.

3.2. Associations between PA and craving

Results of the multilevel model are presented in Table 3. The person-level association between mean PA and craving was not significant (γ01= 5.41, p=.65). The day-level association between day’s PA and craving was also not significant (γ10= −2.86, p=.51). These main effects, however, were qualified by a significant interaction between person-level PA and day-level PA (γ11=.72, p=.02).

Table 3.

Results of the Multilevel Models Examining Associations Between Positive and Negative Affect and Craving

| Fixed Effects | Estimate | Standard Error | |

| Intercept (γ00) | 1310.45* | 180.12 | |

| Day-level PA (γ10) | −2.86 | 4.39 | |

| Day-level NA (γ20) | 28.62* | 4.89 | |

| Time (γ30) | −19.65* | 9.03 | |

| Person-level PA (γ01) | 5.41 | 11.70 | |

| Person-level NA (γ02) | 51.84* | 11.33 | |

| Day-level PA × Person-level PA (γ11) | 0.72* | 0.32 | |

| Day-level NA × Person-level NA (γ21) | 0.53 | 0.31 | |

| Age (γ03) | −22.38 | 20.75 | |

| Gender (γ04) | −203.79 | 388.38 | |

| Random Effects | Estimate | Standard Error | |

| Intercept (γ02) | 2260448 | 408374 | |

| Day-level PA (γ12) | 607.12 | 239.23 | |

| Day-level NA (γ22) | 864.49 | 291.71 | |

| AR(1) | 0.04 | 0.06 | |

| Residual (γ2) | 768496 | 47615 | |

| Fit Indices | |||

| AIC | 12807.60 | ||

| BIC | 12826.00 | ||

Note: Nobservations =764 days nested within 73 persons;

AIC = Akaike information criteria; BIC = Bayesian information criteria.

p < 0.05.

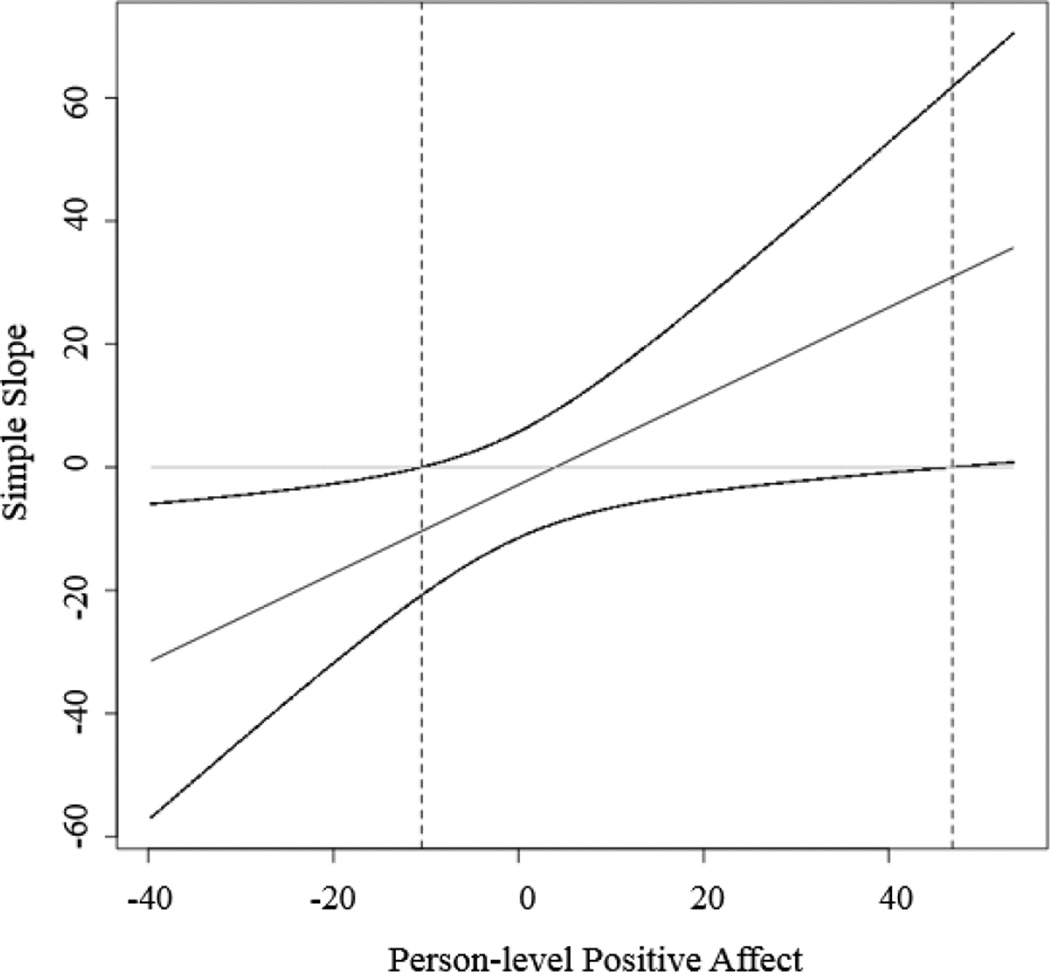

Following up the significant interaction resulted in 95% regions of significance defined by a lower bound of −10.46 and an upper bound of 46.89. As shown in figure 1, these regions imply that the regression of craving on day-level PA is significant and negative at values of person-level PA less than −10.46, not significantly different from zero at values of person-level PA between −10.46 and 46.89, and significant and positive at values of person-level PA greater than 46.89. Given that the minimum and maximum values of (mean centered) person-level PA were −39.65 and 53.45, respectively, the lower region fell within the observed range of person-level PA whereas the upper region fell within the observed range of person-level PA for only one participant (hence it will not be interpreted further).

Figure 1.

The pick-a-point simple slopes of the regression of craving on positive affect at high, medium, and low levels of person-level positive affect. Note: High, medium, and low values of person-level positive affect are defined as plus and minus 1 sd about the mean (−16.07, 0, 16.07). Values for day-level positive affect on the Y-axis were chosen as plus minus 1 sd about the mean (−12.58, 12.58). The slope of the simple regression at low person-level positive affect significantly differs from zero, but the simple slopes at medium and high person-level positive affect do not.

The 95% confidence bands that correspond to these regions are presented in Figure 2. These regions convey that the effect of day-level PA on craving is significant and negative for individuals with low levels of mean person-level PA. More specifically, individuals exhibiting low levels of PA throughout the study experienced higher levels of craving on days of low PA and lower levels of craving on days of high PA.

Figure 2.

The Johnson-Neyman regions of significance and confidence bands for the conditional relation between craving and day-level positive affect as a function of person-level positive affect.

3.3. Associations between NA and craving

The person-level association between mean NA and craving was significant (γ02= 51.84, p < .0001) suggesting that participants exhibiting high NA throughout the study experienced higher craving. The day-level association between day’s NA and craving was also significant (γ20=28.62, p<.0001) suggesting that craving was increased on days when NA was higher than usual. The interaction between day-level NA and person-level NA was not significant (γ21=.53, p=.09).

3.4. Associations between covariates and craving

No significant association emerged between craving and age (γ03=−22.38, p=.28) and gender (γ04=−203.79, p=.60). There was a significant, negative effect of time on craving (γ30=−19.65, p=.03) such that craving decreased from the beginning to the end of the study.

4. Discussion

This study used EMA to measure affect and craving over a 12 day period, allowing for evaluation of the relationship between both person-levels and daily-levels of PA (positive affect) and NA (negative affect) on same day craving in a sample of prescription opiate dependent patients in the early phases of recovery. RW PODPs who reported lower person-levels of positive affect over the course of the 12 day study reported higher levels of craving, but higher craving was only reported on days when these low positive affect individuals were experiencing lower than their average levels of positive affect. This result also indicated that low positive affect days were not associated with higher cravings among RW PODPs who generally reported higher levels of positive affect. In other words, high average positive affect is protective against craving on low positive affect days. Inversely, low average positive affect appears to make RW PODPs vulnerable to low positive affect days. Thus, low positive affect in this sample was not directly linked to high cravings; rather, it created a vulnerability to especially low positive affect days in patients who generally report relatively low positive affect shortly after withdrawal from opiates. In sum, our findings supported the interactive hypothesis for positive affect (1c), but did not support the main effect hypotheses (1a and 1b).

In contrast, our findings suggested negative affect had a more straightforward relationship to craving. Higher average levels of negative affect were linked to higher average cravings regardless of daily levels of negative affect. Similarly, high negative affect on a given day was linked to heightened daily levels of craving, unconditioned by person-level differences in negative affect. These results support the main effects hypotheses for negative affect (2a and 2b), but not the interactive hypothesis (2c).

It is important to emphasize that our models tested the independent effects of positive affect and negative affect. Thus, the main effects of negative affect accounted for the effects of positive affect on cravings. Similarly, the interactive effects of positive affect controlled for the effects of negative affect on cravings.

These results offer a key insight as to the relationship between emotion and craving early in recovery, and may be useful to clinicians in developing strategies to cope with mood swings associated with the post-withdrawal period. In addition, these findings contribute to a growing literature emphasizing the role of low positive affect as a vulnerability factor in relapse to substance abuse, and extends it to a population of prescription opiate dependent patients (e.g., Cook et al., 2004; Hatzigiakoumis et al., 2011; Janiri et al. 2005; Franken et al., 2007; Koob & Le Moal, 2001; Garfield et al., 2014; Volkow et al., 2002). To our knowledge, this study is the first to use EMA to examine the relationship between low positive affect and craving in PODPs. The finding that low daily levels of positive affect are associated with greater same day cravings, but only for individuals with lower general levels of positive affect, provides a nuanced extension of findings from several studies that have used questionnaire measures of low positive affect in alcohol-dependent outpatients (McHugh et al., 2012), as well as EMA studies of nicotine-dependent patients (Bujarski, et al., 2015; Cook et al., 2004; Dunbar et al., 2010; Shiffman et al., 2014; Shiffman & Paty, 2006; Versace et al., 2011); although reports have been mixed in studies of nicotine-dependence (Shiffman et al., 2002; Shiffman & Waters, 2004).

It is worth noting that the interfactor loading between the positive affect and negative affect factors was small and negative (−0.13). This low correlation supports the position that positive affect and negative affect are not opposite ends of the same affective continuum, but rather, represent distinct systems that may predict unique variance in substance use disorders (Cacioppo & Berntson, 1994; Cacioppo et al., 1999; Norman et al., 2011). The finding that low positive affect, at least interactively, predicted a significant degree of variance in craving beyond that of negative affect demonstrates its relative independence, and demonstrated the added value of investigating positive affect as an independent construct, rather than as viewing it as a reciprocal of negative affect.

There are some limitations to this study. First, the data were collected from patients in a residential treatment facility; although this may also be a strength, in that the environment was relatively homogenous across participants, the average experience of RW opiate dependent individuals are likely to be different if they are not in long-term residential treatment. Second, we cannot determine if the low positive affect in this patient sample is due to an allostatic adaptation to drug use or to preexisting traits, or some combination of the two. However, regardless of its etiology, low positive affect appears to present a vulnerability to relapse through its association with increased craving. A longitudinal study that evaluated the re-regulation of positive affect could help promote a better understanding of this question. Likewise, the current EMA study does not link low positive affect to treatment outcome itself, but it does expound on the relationship between low positive affect and a known risk factor for relapse – higher craving. Hypothetically, lower gratification from natural rewards would likely lead to craving drugs of abuse, and subsequent relapse. Research such as this could contribute greatly to emerging models of relapse risk early in recovery. Linking these data to various measures of anhedonia, including both laboratory/experimental and inventory measures, would increase our understanding of both constructs. Finally, EMA methodology allows numerous ways to evaluate the relationships among the variables of interest. The current approach of using day-level averages created highly reliable assessments of mood and craving while minimizing potential biases introduced by missing reports. Other, equally valid methods of analyzing EMA data may shed further light on the relationship between affect and craving.

This study found that, among prescription opiate dependent patients in early abstinence, those who reported relatively lower mean levels of positive affect across the study experienced heightened levels of craving on days when their positive affect was lower than their own average. This finding suggests that there may be a subset of - possibly anhedonic - patients who are particularly vulnerable to craving and relapse when they do not experience their environment as rewarding, independent of negative affect. These results highlight the need for further investigation into the role of low positive affect – in addition to stress and negative affect – among substance abusing populations, and the relationship between low positive affect and the construct of anhedonia. Further studies should examine how the association between low positive affect and craving may relate to treatment outcome in recovering prescription opiate dependent patients. Finally, it would also be important to determine if there are similar relationships between low positive affect, craving, and treatment outcome in substance use disorder patients who abuse drugs other than prescription opiates,.

Highlights.

Ecological Momentary Assessment used to assess mood in prescription opiate patients

Sub-group of opiate patients display reduced positive affect early in recovery

Correlation found between low positive affect and higher drug craving

Rationale for use of ecological momentary assessment in substance abuse research

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01 DA035240-01. DML was supported by T32 DA017629 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and an ISSBD-JJF Mentored Fellowship for Early Career Scholars. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

The authors thank the Caron Treatment Center for hosting the research study, especially Cheryl Knepper, MA, Ken Thompson, MD, and Mike Early for their continued support in our research efforts. The authors would also like to thank William Milchak and Roger Meyer for their ongoing collaborative involvement during the study. This research was supported by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant R01 DA035240. DML was supported by T32 DA017629 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and an ISSBD-JJF Mentored Fellowship for Early Career Scholars. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Abbreviations

- PODP

Prescription opiate dependent patients

- RW

recently withdrawn

- EC

extended care

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Ameringer KJ, Leventhal AM. Applying the tripartite model of anxiety and depression to cigarette smoking: an integrative review. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:1183–1194. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40:373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bovasso GB. Cannabis abuse as a risk factor for depressive symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;158:2033–2037. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bujarski S, Roche DJ, Sheets ES, Krull JL, Guzman I, Ray LA. Modeling naturalistic craving, withdrawal, and affect during early nicotine abstinence: A pilot ecological momentary assessment study. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2015;23(2):81–89. doi: 10.1037/a0038861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Berntson GG. Relationship between attitudes and evaluative space: a critical review, with emphasis on the separability of positive and negative substrates. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115:401. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo JT, Gardner WL, Berntson GG. The Affect System Has Parallel and Integrative Processing Components Form Follow Function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;76:839–855. [Google Scholar]

- Cheetham A, Allen NB, Yücel M, Lubman DI. The role of affective dysregulation in drug addiction. Clinical psychology review. 2010;30:621–634. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JW, Spring B, McCharque D, Hedeker D. Hedonic capacity, cigarette craving, and diminished positive mood. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2004;6:39–47. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook JW, Spring B, McChargue D. Influence of nicotine on positive affect in anhedonic smokers. Psychopharmacology. 2007;192:87–95. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0688-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries TJ, Shippenberg TS. Neural systems underlying opiate addiction. Neuroscience. 2002;22:3321–3325. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-09-03321.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar MS, Scharf D, Kirchner T, Shiffman S. Do smokers crave cigarettes in some smoking situations more than others? Situational correlates of craving when smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2010;12:226–234. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein DH, Willner-Reid J, Vahabzadeh M, Mezghanni M, Lin JL, Preston KL. Real-time electronic diary reports of cue exposure and mood in the hours before cocaine and heroin craving and use. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:88–94. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SG, Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ. Does reducing withdrawal severity mediate nicotine patch efficacy? A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1153–1161. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1153. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First M, Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition. (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Franken IHA, Rassin E, Muris P. The assessment of anhedonia in clinical and non-clinical populations: further validation of the Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS) Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;99:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL, Kahnemann D. Duration neglect in retrospective evaluations of affective episodes. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1993;65:45–55. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.65.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freedman MJ, Lester KM, McNamara C, Milby JB, Schumacher JE. Cell phones for ecological momentary assessment with cocaine-addicted homeless patients in treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfield JBB, Lubman DI, Yucel M. Anhedonia in substance use disorders: A systematic review of its nature, course and clinical correlates. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2014;48:36–51. doi: 10.1177/0004867413508455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH, Ellinwood EH., Jr Cocaine and Other Stimulants. Actions, Abuse and Treatment. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1988;318(18):1173–1182. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198805053181806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gawin FH, Kleber HD. Abstinence symptomatology and psychiatric diagnosis in cocaine abusers. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1986;43:107–113. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800020013003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein RZ, Volkow ND. Dysfunction of the prefrontal cortex in addiction: neuroimaging findings and clinical implications. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2011;12:652–669. doi: 10.1038/nrn3119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzigiakoumis DS, Martinotti G, Giannantonio MD, Janiri L. Anhedonia and Substance Dependence: Clinical Correlates and Treatment Options. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2011;2:10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heilig M, Egli M, Crabbe JC, Becker HC. Acute withdrawal, protracted abstinence and negative affect in alcoholism: are they linked? Addiction biology. 2010;15:169–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinz A, Schmidt LG, Reischies FM. Anhedonia in schizophrenic, depressed, or alcohol dependent patients: neurobiological correlates. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1994;27:7–10. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1014317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janiri L, Martinotti G, Dario T, Reina D, Paparello F, Pozzi G, De Risio S. Anhedonia and substance-related symptoms in detoxified substance-dependent subjects; a correlation study. Neuropsychobiology. 2005;52:37–44. doi: 10.1159/000086176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson PO, Neyman J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their applications to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs. 1936;1:57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kahnemann D, Fredrickson BL, Schreiber CA, Redelmeier DA. When more pain is preferred to less: Adding a better end. Psychological Science. 1993;4:401–405. [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Le Moal M. Drug Addiction, Dysregulation of Reward, and Allostasis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;24:97–129. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00195-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Waters AJ, Kahler CW, Sussman R. Relations between anhedonia and smoking motivation. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11:1047–1054. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM, Chasson GS, Tapia E, Miller EK, Pettit JW. Measuring hedonic capacity in depression: a psychometric analysis of three anhedonia scales. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62:1545. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loas G, Monestes JL, Ingelaere A, Noisette C, Herbener ES. Stability and relationships between trait or state anhedonia and schizophrenic symptoms in schizophrenia: a 13-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Research. 2008;166:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loas G, Salinas E, Pierson A, Guelfi JD, Samuel-Lajeunesse B. Anhedonia and blunted affect in major depressive disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1994;35:366–372. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(94)90277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WR, Jasinski DR, Haertzen CA, Kay DC, Jones BE, Mansky PA, Carpenter RW. Methadone—a reevaluation. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1973;28:286–295. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750320112017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinotti G, Carli V, Tedeschi D, DiGiannantonio M, Roy A, Janiri L, Sarchiapone M. Mono- and Poly-substance dependent subjects differ on social factors, childhood trauma, personality, suicidal behaviour, and comorbid axis I diagnoses Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:790–793. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinotti G, Hatzigiakoumis DS, De Vita O, Clerici M, Petruccelli F, Di Giannantonio M, Janiri L. Anhedonia and Reward System: Psychobiology, Evaluation, and Clinical Features. International Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2012;3:697–713. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Martinotti G, Nicola MD, Reina D, Andreoli S, Focà F, Cunniff A, Tonioni F, Bria P, Janiri L. Alcohol protracted withdrawal syndrome: The role of anhedonia. Substance Use & Misuse. 2008b;43:271–284. doi: 10.1080/10826080701202429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinotti G, Cloninger CR, Janiri L. Temperament and character inventory dimensions and anhedonia in detoxified substance dependent subjects. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2008a;34:177–183. doi: 10.1080/00952990701877078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, Kaufman JS, Frost KH, Fitzmaurice GM, Weiss RD. Positive Affect and Stress Reactivity in Alcohol-Dependent Outpatients. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2013;74:152–157. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2013.74.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller NS, Summers GL, Gold MS. Cocaine dependence: alcohol and other drug dependence and withdrawal characteristics. Journal of Addictive Disorders. 1993;12:25–35. doi: 10.1300/J069v12n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore TM, Seavy A, Ritter K, McNulty JK, Gordon KC, Stuart GI. Ecological momentary assessment of the effects of craving and affect on risk for relapse during substance abuse treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;28:619–624. doi: 10.1037/a0034127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moskowitz DS, Young SN. Ecological momentary assessment: what it is and why it is a method of the future in clinical psychopharmacology. Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience. 2006;31:13–20. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2:119–128. doi: 10.1038/35053570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman GJ, Norris CJ, Gollan J, Ito TA, Hawkley LC, Larsen JT, Berntson GG. Current emotion research in psychophysiology: The neurobiology of evaluative bivalence. Emotion Review. 2011;3:349–359. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ. Conditioning factors in drug abuse: can they explain compulsion? Journal of Psychopharmacology. 1998;12:15–22. doi: 10.1177/026988119801200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Personal communication. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Redelmeier DA, Kahnemann D. Patients' memories of painful medical treatments: Real-time and retrospective evaluations of two minimally invasive procedures. Pain. 1996;66:3–8. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(96)02994-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Dunbar MS, Li X, Scholl SM, Tindle HA, Anderson SJ, Ferguson SG. Smoking Patterns and Stimulus Control in Intermittent and Daily Smokers. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e89911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Gwaltney CJ, Balabanis MH, Liu KS, Paty JA, Kassel JD, Gnys M. Immediate antecedents of cigarette smoking: an analysis from ecological momentary assessment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:531–545. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Paty J. Smoking patterns and dependence: contrasting chippers and heavy smokers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:509–523. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.3.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S, Waters AJ. Negative affect and smoking lapses: a prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:192–201. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith P. Anhedonia: A neglected symptom of psychopathology. Psychological Medicine. 1993;23:957–966. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700026428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS):2000–2010. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services (DASIS Series S-61, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-4701) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Associations of Nonmedical Pain Reliever Use and Initiation of Heroin Use in the US. Center for behavioral Health Statistics and QualityData Review (CBHSQ Data Review, Publication No. DR006) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2002–2012. National Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services (BHSIS Series S-71, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4850) Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman S, Leventhal A. Substance misuse prevention: Addressing anhedonia. New directions for youth development. 2014;2014:45–56. doi: 10.1002/yd.20085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DL, Diener E. Memory accuracy in the recall of emotions. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1990;59:291–297. [Google Scholar]

- Tkacz J, Severt J, Cacciola J, Ruetsch C. Compliance with Buprenorphine Medication-Assisted Treatment and Relapse to Opioid Use. The American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2011.00186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Versace F, Lam C, Engelmann JM, Robinson JD, Minnix JA, Brown VL. Beyond cue reactivity: blunted brain responses to pleasant stimuli predict long-term smoking abstinence. Addiction Biology. 2011;17:991–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Wang GJ, Goldstein RZ. Role of dopamine, the frontal cortex and memory circuits in drug addiction: insight from imaging studies. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 2002;78:610–624. doi: 10.1006/nlme.2002.4099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerberg V, Tonigan J, Miller W. Reliability of Form 90D: An instrument for quantifying drug use. Substance Abuse. 1998;19:179–189. doi: 10.1080/08897079809511386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]