Abstract

This study examined the trajectories of maltreatment severity and substantiation over a 24-month period among children (N = 82,396) with repeated maltreatment reports. Findings revealed two different longitudinal patterns. The first pattern, Elevated Severity, showed a higher level of maltreatment during the initial incident and increased maltreatment severity during subsequent incidents but the substantiation rates for this class decreased over time. The second pattern, Lowered Severity, showed a much lower level of severity, but the likelihood of substantiation increased over time. The Elevated Severity class was comprised of children with an elevated risk profile due to both individual and contextual risk factors including older age, female gender, caregivers’ substance use problems, and a higher number of previous maltreatment reports. Implications of the findings are discussed.

Keywords: maltreatment severity, two-part latent growth curve modeling, recurrence of maltreatment, substantiated maltreatment

During fiscal year 2011 an estimated 3.4 million maltreatment referrals or allegations of child abuse and neglect, referencing almost 6.2 million children, were made to child protection agencies in the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2012). As estimated by the USDHHS (2012), during the past five years approximately 61% of referrals were investigated by child protection workers. A third of these investigations resulted in dispositions of substantiated maltreatment, that is, evidence sustained a finding that at least one child was a victim of maltreatment as defined by state law. If child protection workers did not find sufficient evidence to sustain findings of maltreatment, as defined by state law, their report dispositions concluded that maltreatment was not substantiated.

Repeated Maltreatment Reports

Research has shown that many children referred as being maltreated experienced subsequent victimization. Among youth investigated for maltreatment nationwide between 1 January 2001 and 30 September 2004, approximately 13% experienced a recurrent maltreatment report during the first 6-month post-maltreatment period and an additional 14% experienced a re-report over the following 12-month period (Connell, Bergeron, Katz, Saunders, & Tebes, 2007). In 2011, for children who were confirmed as victims of maltreatment, approximately 6% experienced recurrence of maltreatment within 6 months of the initial incident and slightly more than 27% of children who were reported as being maltreated had a history of prior victimization (USDHHS, 2012). Other research has demonstrated that children previously referred to the child protection system (CPS) were more likely to experience subsequent maltreatment and to experience it sooner than children without prior maltreatment reports (DePanfilis & Zuravin, 1999; Fluke, Yuan, & Edwards, 1999; Levy, Marcovic, Chaudhry, Ahart, & Torres, 1995).

Effects of Repeated Child Maltreatment Reports

Repeated child maltreatment reports have been an issue of public concern because of the large number of negative consequences for the alleged child victims, their families, and society. Re-reports consume considerable resources including additional time and expenses related to multiple investigations, as well as higher costs associated with more services required for children with multiple maltreatment incidents (Connell et al., 2007). In cases where there is a lack of evidence and there is no reason to suspect maltreatment, multiple reports can cause potential disruption of the family and trauma as a result of repeated investigations (Besharov, 1990). Further, multiple reports where investigative conclusions resulted in unsubstantiation due to a lack of proof despite occurrence of maltreatment can further compromise child safety (Giovannoni, 1991). Regardless of maltreatment incident dispositions, research suggests little or no difference between unsubstantiated and substantiated maltreatment cases in terms of child outcomes. For example, Leiter, Myers, and Zingraff (1994) reported no significant differences between children with substantiated and unsubstantiated maltreatment reports on all measured school and delinquency outcomes (i.e., grade point average, absenteeism, behavior problems, and delinquency petitions). Hussey, Marshall, English, Knight, Lau, Dubowitz, & Kotch (2005) showed that child outcomes such as internalizing and externalizing problems, socialization, daily living skills, and mental health did not differ as a function of report disposition. English, Graham, Litrownik, Everson, and Bangdiwala (2005) showed that regardless of substantiation, reports alleging maltreatment were associated with child behavior problems. Finally, researchers have suggested that in most cases regardless of report disposition, maltreatment allegations indicate that some form of maltreatment in fact occurred. If the investigation resulted in dispositions of unsubstantiated maltreatment, it was due to inconclusive evidence or insufficient harm to classify the behavior as “maltreatment” (Drake, 1996; English, Marshall, Brummel, & Orme, 1999; Trocmé, Knoke, Fallon, & MacLaurin, 2009; Winefield & Bradley, 1992).

Studies that examined the effect of substantiation on rates of re-reports also found no difference by the report disposition. For example, English and colleagues (1999) followed 12,239 cases of maltreatment reports for 18 months and concluded that substantiation was not associated with re-reports. Similarly, Drake, Jonson-Reid, Way, & Chung (2003) found that children with unsubstantiated maltreatment and victims of maltreatment who received child protection services were equally likely to experience future maltreatment within 54-month period. These studies suggest the importance of focusing on all children regardless of the report dispositions.

Maltreatment Chronicity and Severity

Although research has demonstrated that maltreatment chronicity is associated with poorer child outcomes (English et al., 2005; Lemmon, 2006; Graham, English, Litrownik, Thompson, Briggs, & Bangdiwala, 2010), little is known about maltreatment severity of repeated incidents and changes in maltreatment severity over time. Understanding maltreatment trajectories and factors associated with these trajectories is important for several reasons. First, chronicity of maltreatment has been shown to be related to a number of adverse outcomes, such as delinquency, aggression, anxiety, and depression (Bolger, & Patterson, 2001; Éthier, Lemelin, & Lacharité, 2004; Lemmon, 2006). Second, more severe maltreatment such as abuse, experienced over a long period of time has been linked to a variety of adverse outcomes, such as behavioral problems (Manly, Cicchetti, & Barnett, 1994), higher levels of trauma symptomatology (Clemmons, Walsh, DiLillo, & Messman-Moore, 2007), anger, poor adaptive functioning, and aggressiveness (Litrownik et al., 2005; Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001). Third, by identifying specific maltreatment trajectories targeted interventions may be developed accounting for specific characteristics of emerged groups. However, most longitudinal studies have not examined maltreatment reports or substantiated maltreatment beyond a second incident (English et al., 1999; Fluke et al., 1999; Fryer & Miyoshi, 1994).

Theoretical Model

Drake’s “harm/evidence model (Drake, 1996) was chosen as a theoretical framework for this study because this model considers a two-dimensional continuum consisting of harm caused by maltreatment and available evidence. Based on this model, substantiation of maltreatment occurs when both harm and strong evidence exist. Unsubstantiated cases, however, may also include harm or potential risk of harm. The contribution of the harm/evidence model and its value for our study is that it highlights the heterogeneity of unsubstantiated cases. Therefore, the implication that can be drawn from this model relates to the possibility of multiple class trajectories in maltreatment substantiation and maltreatment severity.

The harm/evidence model makes clear assumptions about the parallel nature of substantiated reports and the presence of maltreatment, therefore allowing for an examination of substantiation of child maltreatment reports and maltreatment severity as two interrelated processes. These processes may be qualitatively different and, therefore, may be affected by different factors and have varying trajectories over time. However, most studies that examined maltreatment severity have included only substantiated cases in developing measures of severity (Brown & Kolko, 1999; Bryant & Range, 1997; Clemmons et al., 2007; Sprang, Clark, & Bass, 2005). For example, Sprang and colleagues (2005) excluded cases with no maltreatment on their severity scale because their sample consisted of only child victims. Similarly, Brown and Kolko (1999) included only maltreated children referred for treatment. Litrownik and colleagues (2005) used zero values to indicate an absence of a specific maltreatment type and only cases with a summed rating score of 1 or higher across all types of maltreatment were retained for analyses.

Recent methodological advances in longitudinal growth curve analysis have yielded new techniques that allow for simultaneous examination of the maltreatment substantiation process and maltreatment severity over time, as well as accounting for heterogeneity of children with different class trajectories of maltreatment severity and maltreatment substantiation. Specifically, Kim and Muthén (2009) extended growth curve modeling to outcomes that are continuous but non-normally distributed, with the application of the two-part latent growth mixture modeling (LGMM) approach for a dependent variable with a preponderance of zeros. The two-part LGMM offers several advantages: (a) it permits the examination of change and individual differences in an outcome of interest such as maltreatment severity over time; (b) it is efficient in examining a non-normally distributed variable where zero values represent the absence of a particular behavior or an event (Muthén, 2009); (c) it assumes that the population is composed of a mixture of distinct subgroups, each defined by a specific growth curve; and (d) it allows for an examination of the effects of covariates on class-specific growth trajectories.

Present study

The present study sought to examine trajectories of maltreatment severity and substantiation of maltreatment among children with repeated reports using a two-part growth curve mixture model, thus providing an important extension of prior research related to child maltreatment. Given extensive research suggesting interrelationship between maltreatment occurrence and substantiation, we examined trajectories of substantiation and trajectories of maltreatment severity as parallel growth processes. Further, following Drake’s “harm/evidence” model (Drake, 1996), which highlights the heterogeneity of unsubstantiated cases, this study employed mixture modeling approach to test if distinct class trajectories could be identified. Finally, various risk factors were included in the analyses because these factors may affect maltreatment severity and substantiation rates among child welfare involved youth. Specific goals include an examination of (a) changes in maltreatment severity and substantiation over time, (b) latent growth classes for the substantiation process and for changes in maltreatment severity, and (c) the effect of child and maltreatment incident characteristics on class membership and changes over time in substantiation rates and maltreatment severity.

Method

Sample Characteristics

All children in the state of Florida who were referred as being maltreated in fiscal year 2003–2004 and who were subsequently re-reported as being maltreated at least once within 24-month period were included in the study (N = 82,396). These children and their families were visited by child protection investigators and the dispositions of the child maltreatment reports were recorded. The study population consisted of 49% males. Children’s age at the time they were referred to the CPS ranged from birth to 18 years (M = 8.72, SD = 4.93) and 41% were children identified as members of an ethnic minority group (i.e., race/ethnicity other than European American). Approximately, one-third of these children (n = 24,119) were reported as being maltreated at least three or more times during the study period (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics (N=82,396)

| N | % | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (male) | 40,374 | 49.0 | ||

| Minority status | 33,782 | 41.0 | ||

| Child age | 8.72 | 4.93 | ||

| Number of prior reports | 2.87 | 2.56 | ||

| Type of maltreatment | ||||

| Abuse | 28,839 | 35.0 | ||

| Neglect | 28,015 | 34.0 | ||

| Threatened harm | 24,719 | 30.0 | ||

| Caregiver absence | 1,236 | 1.5 | ||

| Parental substance abuse | 44,906 | 54.5 |

Study Design

The study design consisted of a longitudinal analysis of administrative data based on an entry cohort (i.e., children who were first reported within fiscal year 2003–2004) with three measurement occasions. Because 53% of maltreatment re-reports occurred during the first three months, and just a few second reports took place during each subsequent month, the measurement occasions were spaced at uneven intervals. Thus, maltreatment incidents were scored during the first seven days of the first report receipt, the next three months, and the remainder 21 months of the study period. These time intervals were selected to reflect the natural distribution of the maltreatment reports and to comply with the requirements of Mplus software, which allows for covariance coverage at a minimum acceptable value of .001, that is all variables and pairs of variables have to have data for at least 1% of the sample (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010). A number of children (n = 494) experienced substantiated maltreatment more than once during a single measurement period. In those cases the incident with the maximum severity score was chosen for analyses (Gruenewald, Johnson, Light, & Saltz, 2003).

Maltreatment Severity Measure

An index of maltreatment severity was constructed based on both theoretical and empirical justifications. Theoretical justification references both hierarchical and cumulative frameworks. The hierarchical approach assumes that some types of maltreatment are inherently more detrimental than others due to stronger violation of social norms and due to active (e.g., abuse) versus passive (e.g., neglect) nature of these maltreatment types (Boxer & Terranova, 2008; Lau, Leeb, English, Graham, Briggs, Brody, & Marshall, 2005; Manly et al., 1994). The cumulative approach is based on the cumulative risk model, which asserts that the number of maltreatment experiences, apart from the specific types of maltreatment experienced, is more important when predicting adverse outcomes, and that multiple maltreatment experiences increase the likelihood of such events (Rutter, 1979). At the practical level, including each maltreatment subtype and their hierarchy in the maltreatment severity measure was reflective of both child welfare practice in Florida and the means to document comprehensive maltreatment information as recorded in administrative data sets.

Hierarchical classification within the severity measure was based on the maltreatment ranking developed by Smith and Testa (2002), where abuse was considered as the most serious maltreatment and threatened harm the least. Therefore, to indicate any abuse, a score of 3 was used. A score of 2 was assigned to neglect and a score of 1 was assigned to threatened harm. Similar to the maltreatment classification used by Clemmons et al. (2007) and Lemmon (2006), a 0 score was used to indicate the absence of a maltreatment type. Conceptualizing each type of maltreatment as an additional score on the maltreatment severity measure was based on a cumulative classification model. There were up to eight specific occurrences of maltreatment per incident recorded in the Florida child welfare information system and each specific occurrence of maltreatment was classified into three maltreatment types. For example, if a child had a broken leg and burns, abuse as the type of maltreatment would be counted twice; if a child experienced medical neglect, inadequate supervision, and inadequate shelter, neglect as the type of maltreatment would be counted three times. Thus, the severity measure had scores ranging from 1 to 24, with higher scores representing greater severity (at time 1: M = 1.95, SD = 2.79; at time 2: M = 2.01, SD = 2.86; and at time 3: M = 2.19, SD = 2.96).

Maltreatment Report Substantiation

There are three categories of dispositions recorded in the Florida administrative data set. These include unsubstantiated maltreatment, some indication of maltreatment, and substantiated maltreatment. In this study, cases with some indication of maltreatment were regarded as substantiated maltreatment because this disposition means there is reason to suspect that the child was maltreated or is at risk of maltreatment although there is not enough evidence to confirm maltreatment (Florida Department of Children and Families, 2009). To adequately capture the information about report disposition and Florida child protection investigation practice, a 0 score was assigned if maltreatment was unsubstantiated, whereas a score of 1 was assigned if the report disposition was either substantiated maltreatment or some indication of maltreatment.

Predictor Variables

Predictor variables selected for the analyses have been shown in prior studies to significantly affect either maltreatment substantiation or severity (King, Trocme, & Thatte, 2003; Sprang et al., 2005). Predictors included child demographic characteristics such as gender (coded as 1 if male and 0 if female), minority status defined as any race/ethnicity other than European American, age at the time of the first (i.e., after the beginning of this study) maltreatment report, a child’s prior maltreatment reports (i.e., allegations of maltreatment reported prior to the beginning of this study), caregiver(s) substance use (coded as 1 if present and 0 if not), types of maltreatment (i.e., abuse, neglect, threatened harm), and absence of a caregiver (i.e., loss of a caregiver due to death, incarceration or abandonment). As described in Chapter 39, Florida Statutes (Florida Statutes, 39.01, 2006), abuse was defined as any willful act or threatened act that results in any physical, mental, or sexual injury or harm that causes or is likely to cause the child’s health to be significantly impaired. Neglect was defined as deprivation of necessary food, clothing, shelter, or medical treatment or a condition when a child is permitted to live in an environment when such deprivation causes the child’s physical or mental health to be significantly impaired. Threatened harm was defined as a behavior that is not accidental and is likely to result in harm to the child. Because type of maltreatment during the first episode was included in the construction of the severity measure, this predictor was omitted from the equation for maltreatment severity during the first episode to avoid contamination between a covariate and the dependent variable.

Data Sources

Florida’s child welfare information system, the Florida Safe Families Network (FSFN), was the primary source of data for this study. This database contains records of all children in Florida who were reported as being maltreated including information about maltreatment reports, results of child protection investigations, and maltreatment incidents. It allows for tracking children over time and location in Florida by using the same child identification number and it contains dates when maltreatment reports were received, therefore allowing for longitudinal analyses.

Analytic Approach

To address the goals of the study, the data were modeled using a two-part latent growth curve mixture model. This strategy was selected for several reasons. First, inclusion of unsubstantiated reports in the development of a severity measure led to the utilization of zeros as an indicator of maltreatment absence – that is, if a report was unsubstantiated, maltreatment severity was scored as a zero. Thus, one part of our analytic model describes the change in substantiation status as a function of time, with addition of the random error about the individual curve. In Florida, approximately 50% of maltreatment reports were unsubstantiated. Second, these zeros do not represent missing values or negative responses but rather reflect the absence of a behavior (i.e., substantiated maltreatment) and therefore severity cannot be assessed. The absence of maltreatment could occur for two reasons. One reason is that the child protection investigator might not find sufficient evidence to sustain findings of maltreatment at that time, therefore creating a sampling zero. Alternatively, the absence of a problem could be due to the fact that child maltreatment never happened and hence was a structural zero. For substantiated cases, a severity score was available, ranging from 1 to 24, and therefore was analyzed as the second part of the model.

Third, a two-part latent growth curve mixture model was selected because other common analytic approaches cannot be used on these data. Non-normally distributed data with a high frequency of zeros, referred to as semi-continuous data, cannot be normalized using transformations (Delucchi, & Bostrom, 2004). Standard statistical techniques (e.g., conventional growth models), would fail to differentiate between the likelihood of finding substantiated maltreatment (zeros) and the level of severity (scores from 1 to 24). Similarly, semiparametrical approaches based on generalized estimating procedures would not be able to recognize qualitative distinctions between zeros and non-zero responses (Zeger, Liang, & Albert, 1988). A zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) model also has limitations for dealing with semi-continuous data (Lambert, 1992; Xie, Hur, & McHugo, 2000) as do finite mixture growth models and latent transition models (Blozis, Feldman, & Conger, 2007).

Two-part random-effects models that deal with semi-continuous longitudinal data are particularly suited to our type of data (Kim, & Muthén, 2009; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010; Olsen & Schafer, 2001). Two-part models divide semi-continuous data into two parts. One part models a binary variable that indicates whether the event/behavior took place (Kim, & Muthén, 2009). In this study the binary variable indicates whether maltreatment occurred or not (i.e., was substantiated or not). The other part models a continuous variable that indicates the severity of maltreatment, if maltreatment occurred. This variable consists of positive values that are the log of the original positive values (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010). If no maltreatment occurred, the severity of maltreatment variable is coded as missing. The binary and continuous variables depend on each other, that is, the continuous part (maltreatment severity) can be assessed only if there is a positive response on the binary part (substantiation of maltreatment). Thus, substantiation of maltreatment reports is treated as a binary process and level of severity is treated as a continuous process over time. Although the two processes are qualitatively distinct, a two-part latent growth curve model allows for simultaneous analysis of changes in each part of the model and for the examination of different sets of covariates associated with each process.

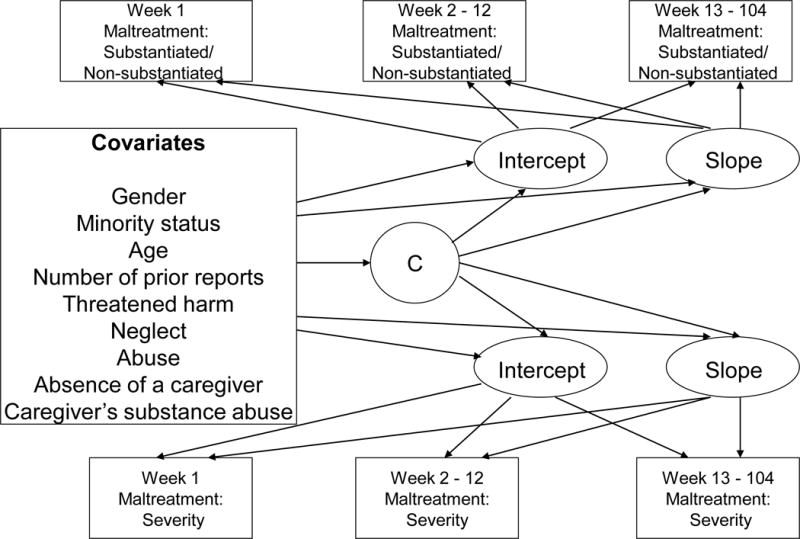

This basic two-part latent growth curve model can be extended to a two-part latent growth curve mixture model that allows for discrete patterns of growth trajectories in reports and severity over time. A mixture distribution for each part of the model consists of two or more patterns of growth. Specifically, for the substantiation part of the model, the mixture distribution may consist of unobserved groups (classes) of children with different trajectories of substantiation. One trajectory class may have a low, flat rate of re-reporting while another class may have increasing risk over time. Similarly, a mixture distribution for the continuous part of the model may represent several classes of children with different maltreatment severity trajectories. Additionally, a mean growth curve can be estimated for each class in each part of the model, and the model may include different covariates for each class of the model (see Figure 1). Overall, the selected analytic strategy allows for examinations of (a) changes over time in the outcome of interest, (b) individual differences, (c) correlates of predictors of change, (d) unobserved subgroups of individuals following class specific trajectories, and (e) unobserved heterogeneity separately for binary and continuous processes. A two-part latent growth curve mixture model was estimated using Mplus version 6.11 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010).

Figure 1.

A Diagram for the Two-Part Latent Growth Curve Mixture Model

Missing Data

Mplus MISSING feature was used to impute missing data for dependent variables. This imputation process results in means and variances that are less biased than those using alternative approaches to dealing with missing data, such as listwise deletion or mean substitution. The Mplus software uses a full information maximum likelihood estimation under the assumption that the data are missing at random (MAR; Arbuckle, 1996; Little, 1995). Mplus missing data module will help to optimally use the data available for children who will be lost to follow-up.

Results

Model Selection and Model Fit

Because building a two-part latent growth curve mixture model is a complex process, modeling was conducted in a step-sequential approach. Model construction consisted of three steps. The first step included fitting the growth curve form for the data. The functional forms of the curves were assessed separately for each part based on available fit indices including model log-likelihood values, Akaike Information Criteria (AIC; Akaike, 1974), and Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC; Schwartz, 1978). Both AIC and BIC are measures of the goodness of fit of the estimated statistical model for the data that adjust for the complexity of the extended model and reward for parsimony when comparing different models (Muthén & Muthén, 2000). Lower BIC and AIC values are indicative of a better fitting model. Both the binary curve for substantiation (Y/N) and for maltreatment severity were best modeled as linear growth curves.

During the second step of model construction, a series of unconditional models consisting of 1- through 3-class solutions for both binary and continuous parts were examined for goodness of fit. These models were examined based on available fit indices including log-likelihood values of the models, AIC, BIC, and Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin likelihood ratio test (LRT; Lo, Mendell, & Rubin, 2001). LRT compares the estimated model with a model with one less class than the estimated model (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010). Lower BIC and AIC values and significant LRT indicate a better fitting model. In addition, entropy values were assessed. Entropy is a measure of classification accuracy based on probabilities of a class membership for each individual (Ramaswamy, DeSarbo, Reibstein, & Robinson, 1993). It ranges from 0 to 1.0. Entropy values that are closer to 1.0 indicate better classification accuracy.

Latent growth mixture models often cannot be identified without some parameter restrictions, so for purpose of model identification the variance of the slope on the binary part and the variance of the slope on the continuous part were constrained to zero (Muthén & Shedden, 1999). Therefore, this model estimated only fixed effects for changes in substantiation rates and levels of maltreatment severity over time. The growth factor covariance between the intercept of the binary part of the model and the slope of the continuous part was fixed at zero to stabilize the model estimation (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010).

When a one-class solution was compared with a two-class solution, all fit indices indicated that the two-class solution improved the model (see Table 1). Although some model indices (i.e., BIC and AIC) improved with the three-class solution, Pearson Chi-Square and the log-likelihood values were not replicated. As indicated by Hipp and Bauer (2006), this increases the chance that the selection of a final model (e.g., the best number of latent trajectory classes) will be misinformed and that it is imperative to compare the substantive results of the key solutions obtained. It appears that an extra class did not provide additional information and was not qualitatively different from one of the classes in the two-class solution. Therefore, the two-class solution unconditional model was identified as best-fitting based on examined fit indices and interpretability of classes. The third stage of analyses consisted of the examination of the conditional model where children’s demographic characteristics and variables describing maltreatment history were included as covariates (see Figure 1).

Unconditional Analyses

As shown in Table 1, the model yielded two classes. In the two-class solution, 64,266 (77%) children had a higher probability of belonging to the first class and 19,197 (23%) to the second. Within the two-class solution model all freely estimated means for the growth parameters and random variances for the intercepts of both binary and continuous parts in class 1 and class 2 were significant (p < .05). Variances for the slopes of the binary and continuous parts were fixed at zero. When the parameter estimates for the larger class 1, labeled as Elevated Severity, were examined, we found a significant negative intercept of the binary part (β = −0.18, S.E. = 0.04, pseudo-z = −4.09) indicating a lower probability of maltreatment substantiation during the initial incident and a significant positive slope of the continuous part (β = 0.10, S.E. = 0.01, pseudo-z = 48.58) showing increasing levels of maltreatment severity during subsequent substantiated incidents. For the smaller class 2, labeled Lowered Severity, we found a significant positive slope of the binary part (β = 0.17, S.E. = 0.07, pseudo-z = 2.61) and negative slope of the continuous part (β = −0.14, S.E. = 0.01, pseudo-z = −42.13), indicating the trend of an increase in probability of report substantiation, but a decrease of maltreatment severity over time.

Conditional Latent Growth Curve Mixture Model

In the conditional latent growth curve mixture model, covariates were regressed on binary and continuous parts of the model and the relationships between covariates and each latent class were estimated. The fit of the two-class unconditional latent growth curve mixture model was compared to the model with covariates. Based on AIC and BIC, the overall model fit substantially improved compared to the unconditional model. The conditional growth mixture model with a two-class solution had substantially lower BIC (454,431.56) and lower AIC (453,658.94) compared to the unconditional model (BIC = 475,934.56 and AIC = 475,794.58).

Between-Class Covariates

Because the Elevated Severity class comprised the largest number of children and these children experienced increased levels of maltreatment severity over time, the effect of covariates on the probability of being in this class was assessed. Both child and caregiver characteristics were identified as significant predictors of the membership in the Elevated Severity class. Examination of odds ratios revealed that compared to the Lowered Severity class, children in the Elevated Severity class were more likely to be females, European American, and they were more likely to be older. Each year of age (i.e., being one year older) corresponded to a 4% increase in being in the Elevated Severity class. Children who were neglected (OR = 1.66, p < 0.05), those who came from families with substance use problems (OR = 1.59, p < 0.05), and those with prior maltreatment reports (OR = 1.10, p < 0.05) were more likely to be in the Elevated Severity class with one additional report corresponding to a 10% increase in odds of being in this class.

Within-Class Covariates

The associations between covariates and class-specific (e.g., predicting slope within class) growth parameters for each class were also examined. Table 2 shows that for the Elevated Severity class, being female, European American, having a higher number of prior maltreatment reports, and caregiver loss uniquely predicted increased rates of substantiated maltreatment during subsequent maltreatment episodes. For the Lowered Severity class, however, increased rates of substantiated maltreatment during subsequent maltreatment episodes were associated with younger age, being abused, and caregiver’s substance use problems.

Table 2.

Model Fit for Unconditional Two-Part Latent Growth Mixture Models

| Fit Index | One-class solution | Two-class solution for both parts of the model | Three-class solution for both parts of the model* |

|---|---|---|---|

| # of free parameters | 10 | 15 | 20 |

| Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) | 479718.91 | 475934.56 | 473777.20 |

| Akaike information criterion (AIC) | 479625.59 | 475794.58 | 473590.55 |

| Log-Likelihood | −239802.80 | −237882.29 | −236775.28 |

| Likelihood ratio test (LRT) | n/a | 3774.40 (p < 0.01) |

2069.51 |

| Entropy | n/a | 0.469 | 0.379 |

Note.

The best log-likelihood value was not replicated.

When the association between the covariates and class-specific trajectories of maltreatment severity was examined, an effect was observed for the regression of the slope on gender, race/ethnicity, the number of prior reports, and caregiver’s substance use problem for both classes. Females, European Americans, children with a higher number of maltreatment reports, and those whose caregivers had substance use problems experienced higher levels of maltreatment severity over time. Younger age was associated with increased maltreatment severity levels over time for the Elevated Severity class, and abuse or neglect were associated with higher levels of maltreatment severity over time the Lowered Severity class. In both classes, caregivers’ substance use problems were associated with higher levels of maltreatment severity during the initial episode and more severe maltreatment over time.

Discussion

Using two-part latent growth curve mixture modeling we examined changes in maltreatment substantiation and levels of severity over a 24-month period among children with repeated maltreatment reports. This approach represents an advanced technique beyond that used in many prior longitudinal studies. It was valuable in assessing maltreatment simultaneously on two dimensions, that is, the occurrence of maltreatment substantiation and level of maltreatment severity. In addition, it allowed for simultaneous exploration of latent class trajectories and the effect of covariates on the slope and intercept for each class.

Results from the conditional growth mixture model revealed that children who were reported as being maltreated followed different patterns, and they provided support for two latent trajectory classes. The prevalent pattern showed a higher level of maltreatment severity during the initial incident and increased levels of maltreatment severity during subsequent substantiated incidents. The substantiation rates for this Elevated Severity class, however, decreased over time. Compared to this larger class, the Lowered Severity class was characterized by a much lower level of severity during the initial episode and lower levels of maltreatment severity during subsequent substantiated incidents. The likelihood of substantiation in this class increased over time. These findings broaden the existing harm/evidence model that suggests the heterogeneity of unsubstantiated reports (Drake, 1996) and highlight the variation in the continuum of maltreatment substantiations as well as the difference in children’s maltreatment experiences.

From a theoretical point of view these groups represent different types of cases that are influenced by multiple factors and are likely to have different outcomes. From a practical point of view, the identified trajectories of maltreatment severity and substantiation may indicate responses to service provision. Because in most states, including Florida, substantiation is necessary for service provision, families in the Lowered Severity class may be demonstrating responsiveness to services and additional surveillance provided by the system. As a result, their maltreatment severity decreased over time. However, families of children in the Elevated Severity class, specifically those families with subsequent substantiated maltreatment reports, do not seem to respond to provided services, or possibly the amount or quality of services these families receive is insufficient. This class is consistent with previous research indicating that chronic cases with high problem levels often show limited improvement during service provision (Chaffin, Bard, Hecht, & Silovsky, 2011). At the same time, these cases might raise additional concern among teachers and counselors, which in turn leads to an increased number of unsubstantiated reports.

In light of the finding that maltreatment severity increased over time for a substantial proportion of children, factors that distinguish classes of children with increased versus decreased levels of severity were examined. It appears that the Elevated Severity class comprises children with an elevated risk profile due to both individual and contextual risk factors. Relative to the class of Lowered Severity, children in the Elevated Severity class were older, more likely to be female, experienced more serious types of maltreatment such as abuse and neglect, had caregivers with substance use problems, and had a higher number of previous maltreatment reports. This is consistent with previous studies, which have demonstrated relations between child characteristics and recurrence of maltreatment as well as caregivers’ substance use and maltreatment severity (DePanfilis, & Zuravin, 1999; Sprang et al., 2005). However, while prior research indicated the link between multiple risk factors and child adverse outcomes, this study suggests a differential effect based on both child and family characteristics.

Although the findings highlighted heterogeneity, interesting similarities were revealed as well. Children in both Elevated Severity and Lowered Severity classes were more likely to experience higher levels of maltreatment severity if they had greater number of prior maltreatment reports and if they came from families with substance use problems. These findings are consistent with other studies that demonstrated a significant effect of prior maltreatment experiences and presence of substance use problems on re-referrals, recurrence of maltreatment, and severity of incidents (Connell et al., 2007; English, et al., 1999; Fluke et al., 1999; Sprang et al., 2005). A finding unique to this study is that parental substance use is related to repeated maltreatment substantiation and elevated maltreatment severity over time.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to examine heterogeneity of maltreated children and identify different subgroups of children based on unique trajectories for maltreatment severity and maltreatment substantiation. The findings of this study also contribute to the literature on child maltreatment by examining predictors associated with class membership and by assessing longitudinal patterns of change in maltreatment severity and substantiation beyond two time points. Moreover, using a novel approach – two-part mixture latent growth modeling – this study examined the interrelation between two processes (i.e., maltreatment severity and maltreatment substantiation) and the effect of covariates for each process.

Limitations

Limitations of the study should be noted. First, this study relied on administrative data. Although administrative data sets have a number of advantages (Pandiani & Banks, 2003), their shortcomings include incomplete or inaccurate records, unavailability of certain important data elements (e.g., presence of mental health problems, daycare or school attendance), inconsistent coding of maltreatment incidents, and regional differences. Second, the construction of the severity measure was based on administrative data and was therefore limited to available data elements. Third, unavailability of data related to the type of maltreatment and available evidence in the course of investigation precluded an examination of the effect of maltreatment type on report disposition. Fourth, children were followed up for only 24 months; thus it is not known whether the trajectories hold true beyond this time period. Finally, certain child and parent characteristics, such as child externalizing behavior, and parental stress level shown to be associated with maltreatment severity (Hegar, Zuravin, & Orme, 1994; Sprang et al., 2005) were not examined due to unavailability of this information. More longitudinal research that examines the effect of caregiver characteristics on maltreatment severity and substantiation over time is needed to understand whether these characteristics affect maltreatment experiences for children.

Implications

Findings from this study can help inform child welfare service providers and child maltreatment researchers. From the perspective of child welfare service providers, the finding that a considerable proportion of cases (i.e., larger class Elevated Severity) had elevated maltreatment severity suggests that identification of this group is important for intervention purposes. Because families in this group represent chronic cases, both in terms of recurrence of substantiated maltreatment and higher maltreatment severity, longer term interventions that focus on maintenance and monitoring and which incorporate a harm reduction approach might be more useful. Also, child welfare workers may need to assist families with obtaining social support and link them with appropriate community services following child protection investigation.

Although, our findings indicated that older children were more likely to be in the Elevated Severity class, when specific predictors for the severity trajectory in this class were examined, younger child age and having parents with substance abuse issues were associated with increased level of severity over time. Therefore, child welfare staff should pay special attention to younger children with parental substance use histories already known to the system because they are at highest risk for increased levels of maltreatment severity over time. Therefore, special considerations (e.g., increased monitoring of caregivers by case managers) should be given when child protection workers develop case plans and make decisions regarding placement for the child. Overall, it is critical that interventions meet caregivers and children’s individual needs and are informed by findings from current research.

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates and Standard Errors for Conditional Growth Mixture Model

| Substantiation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Class 1 Elevated Severity |

Class 2 Lowered Severity |

|||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Covariates | Estimates for the intercept | S.E. | Estimates for the slope | S.E. | Estimates for the intercept | S.E | Estimates for the slope | S.E |

| Gender | 0.01 | 0.03 | −0.02* | 0.01 | −0.03 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Minority status | −0.13* | 0.03 | −0.02* | 0.01 | −0.02 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Age | −0.03* | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.04* | 0.01 | −0.01* | 0.01 |

| Number of prior reports | −0.01* | 0.01 | 0.01* | 0.01 | −0.02* | 0.01 | −0.01* | 0.01 |

| Maltreatment type | ||||||||

| Abuse | 0.07 | 0.04 | −0.03* | 0.01 | −0.47* | 0.09 | 0.08* | 0.02 |

| Neglect | −0.12* | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.01 | −0.09 | 0.08 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Caregiver loss | −0.54* | 0.09 | 0.14* | 0.03 | −1.16* | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Substance abuse | 0.54* | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.29* | 0.05 | 0.05* | 0.01 |

|

| ||||||||

| Severity | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Class 1 | Class 2 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Covariates | Estimates for the intercept | S.E. | Estimates for the slope | S.E. | Estimates for the intercept | S.E | Estimates for the slope | S.E |

|

| ||||||||

| Gender | 0.04* | 0.01 | −0.01* | 0.01 | 0.06* | 0.01 | −0.02* | 0.01 |

| Minority status | −0.02* | 0.01 | −0.01* | 0.01 | −0.05* | 0.01 | −0.01* | 0.01 |

| Age | 0.02* | 0.01 | −0.01* | 0.01 | 0.01* | 0.01 | −0.01 | 0.01 |

| Number of prior reports | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01* | 0.01 | 0.01* | 0.01 | 0.01* | 0.01 |

| Type of maltreatment | ||||||||

| Abuse | n/a | n/a | −0.02* | −0.02* | n/a | n/a | 0.22* | 0.01 |

| Neglect | n/a | n/a | −0.11* | 0.01 | n/a | n/a | 0.13* | 0.01 |

| Caregiver loss | −0.06 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.02 |

| Substance abuse | 0.04* | 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.14* | 0.02 | 0.04* | 0.01 |

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank members of the Prevention Science and Methodology Group for their thoughtful comments. (This Group has been supported by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Institute on Drug Abuse through grant 5R01MH40859)

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Dr. Bengt Muthén for his consultations regarding the analytic approach and Mplus programming.

Contributor Information

Svetlana Yampolskaya, Department of Child and Family Studies, University of South Florida

Paul E. Greenbaum, Department of Child and Family Studies, University of South Florida

C. Hendricks Brown, Department of Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Miami.

Mary I. Armstrong, Department of Child and Family Studies, University of South Florida

References

- Akaike H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control. 1974;19:716–723. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle J. Full information estimation in the presence of incomplete data. In: Marcoulides G, Schumacker R, editors. Advanced structural equation modeling: Issues and techniques. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 243–277. [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J. Etiology of child maltreatment. A developmental-ecological analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1993;114:413–434. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.114.3.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bersharov D. Gaining control over child abuse reports. Public Welfare. 1990;48:34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Blozis SA, Feldman B, Conger RD. Adolescent alcohol and adult alcohol disorders: A two-part random-effects model with diagnostic outcomes. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;88:85–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ. Developmental pathways from child maltreatment to peer rejection. Child Development. 2001;72:549–568. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boxer P, Terranova AM. Effects of multiple maltreatment experiences among psychiatrically hospitalized youth. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:637–647. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Brown EJ, Kolko DJ. Child victims attributions about being physically abused: An examination of factors associated with symptom severity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27:311–322. doi: 10.1023/a:1022610709748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant SL, Range LM. Type and severity of child abuse and college students’ lifetime suicidality. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1997;21:1169–1176. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00092-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaffin M, Bard D, Hecht D, Silovsky J. Change trajectories during home-based services with chronic child welfare cases. Child Maltreatment. 2011;16:114–125. doi: 10.1177/1077559511402048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance T, Scannapieco M. Ecological correlates of child maltreatment: Similarities and differences between child fatality and nonfatality cases. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal. 2002;19:139–161. [Google Scholar]

- Clemmons JC, Walsh K, DiLillo D, Messman-Moore TL. Unique and combined contributions of multiple child abuse types and abuse severity to adult trauma symptomatology. Child Maltreatment. 2007;12:172–181. doi: 10.1177/1077559506298248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connell CM, Bergeron N, Katz KH, Saunders L, Tebes JK. Re-referral to child protective services: The influence of child, family, and case characteristics on risk status. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2007;31:573–588. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delucchi KL, Bostrom A. Method for analysis of skewed data distributions in psychiatric clinical studies: Working with many zero values. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1159–1168. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.7.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePanfilis D, Zuravin SJ. Predicting child maltreatment recurrences during treatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:729–743. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drake B. Unraveling “unsubstantiated. Child Maltreatment. 1996;1:261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Jonson-Reid M, Way I, Chung S. Substantiation and recidivism. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:248–260. doi: 10.1177/1077559503258930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Graham JC, Litrownik AJ, Everson M, Bangdiwala SI. Defining maltreatment chronicity: Are there differences in child outcomes? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:575–595. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Marshall DB, Brummel S, Orme M. Characteristics of repeated referrals to child protective services in Washington state. Child Maltreatment. 1999;4:297–307. [Google Scholar]

- Éthier LS, Lemelin JP, Lacharité C. A longitudinal study of the effects of chronic maltreatment on children’s behavioral and emotional problems. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:1265–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Florida Department of Children and Families. Annual report to the legislature: False reports of child abuse, neglect or abandonment referred to law enforcement, FY2007-2008. 2009 Mar; Retrieved from http://www.dcf.state.fl.us/fs_childwelfare/docs/2009LMRs/S09_003473_2009NumberFalseReprotLawEnf.pdf.

- Proceedings Relating to Children, 5 Fl stat., §§ 39-3901(2006).

- Fluke JD, Shusterman GA, Hollinshead DM, Yuan YT. Longitudinal analysis of repeated child abuse reporting and victimization: Multistate analysis of associated factors. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:76–88. doi: 10.1177/1077559507311517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluke JD, Yuan YT, Edwards M. Recurrence of maltreatment: An application of the national child abuse and neglect data system (NCANDS) Child Abuse & Neglect. 1999;23:633–650. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer GE, Miyoshi TJ. A survival analysis of revictimization of children: The case of Colorado. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1994;18:1963–1071. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller T, Nieto M. Substantiation and maltreatment rereporting: A propensity score analysis. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14:27–37. doi: 10.1177/1077559508326925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannoni JM. Unsubstantiated reports: Perspective of child protection workers. Child and Youth Services. 1991;15:51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Graham JC, English DJ, Litrownik AJ, Thompson R, Briggs EC, Bangdiwala SI. Maltreatment chronicity defined with reference to development: Extension of the social adaptation outcome findings to peer relations. Journal of Family Violence. 2010;25:311–324. [Google Scholar]

- Gruenewald PJ, Johnson FW, Light JM, Saltz RF. Drinking to extremes: Theoretical and empirical analyses of peak drinking levels among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2003;64:817–824. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2003.64.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegar RL, Zuravin SJ, Orme JG. Factors predicting severity of physical child abuse injury: A review of the literature. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1994;9:170–183. [Google Scholar]

- Hipp JR, Bauer DJ. Local solutions in the estimation of growth mixture models. Psychological Methods. 2006;11:36–57. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.11.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, Knight ED, Lau AS, Dubowitz H, Kotch JB. Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: Distinction without difference? (2005) Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inkelas M, Halfon N. Recidivism in child protective services. Children and Youth Services Review. 1997;19:139–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kim YK, Muthén B. Two-part factor mixture modeling: Application to an aggressive behavior measurement instrument. Structural Equation Modeling. 2009;16:602–624. doi: 10.1080/10705510903203516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King G, Trocme N, Thatte N. Substantiation as a multitier process: The results of a NIS_3 analysis. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:173–182. doi: 10.1177/1077559503254143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert D. Zero-inflated Poisson regression, with an application to defects in manufacturing. Technometrics. 1992;34:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, Leeb RT, English D, Graham JC, Briggs EC, Brody KE, Marshall JM. What’s in a name? A comparison of methods for classifying predominant type of maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:553–551. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter J, Myers KA, Zingraff MT. Substantiated and unsubstantiated cases of child maltreatment: Do their consequences differ? Social Work Research. 1994;18:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Lemmon JN. The effects of maltreatment recurrence and child welfare services on dimensions of delinquency. Criminal Justice Review. 2006;31:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Levy HB, Markovic J, Chaudhry U, Ahart S, Torres H. Reabuse rates in a sample of children followed for 5 years after discharge from a child abuse inpatient assessment program. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19:1363–1377. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00095-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ. Modeling the dropout mechanism in repeated-measures studies. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90:1112–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Litrownik AJ, Lau A, English DJ, Briggs E, Newton RR, Romney S, Dubowitz H. Measuring the severity of child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:553–573. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Y, Mendell NR, Rubin DB. Testing the number of components in a normal mixture. Biometrika. 2001;88:767–778. [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Cicchetti D, Barnett D. The impact of subtype, frequency, chronicity, and severity of child maltreatment on social competence and behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children’s adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory class. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2000;24:882–891. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Shedden K. Finite mixture modeling with mixture outcomes using EM algorithm. Biometrics. 1999;55:463–469. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Sixth. Los Angeles, CA: Author; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen MK, Schafer JL. A two-part random-effects model for semicontinuous longitudinal data. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2001;96:730–745. [Google Scholar]

- Pandiani JA, Banks SM. Large data sets are powerful. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:745. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.5.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy V, DeSarbo W, Reibstein D, Robinson W. An empirical pooling approach for estimating marketing mix elasticities with PIMS data. Marketing Science. 1993;12:103–124. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Protective factors in children’s responses to stress and disadvantage. In: Kent MW, Rolf EJ, editors. Primary prevention of psychopathology Social competence in children. Hanover, NH: University of New England Press; 1979. pp. 49–74. [Google Scholar]

- Schnitzer PG, Ewigman BG. Child deaths resulting from inflicted injuries: Household risk factors and perpetrator characteristics. Pediatrics. 2005;116:687–694. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz G. Estimating the dimension of a mode. The Annals of Statistics. 1978;6:461–464. [Google Scholar]

- Smith BD, Testa MF. The risk of subsequent maltreatment allegations in families with substance-exposed infants. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26:97–114. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00307-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprang G, Clark JJ, Bass S. Factors that contribute to child severity: A multi-method and multidimensional investigation. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:335–350. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud J, Pritchard C. Child homicide, psychiatric disorder, and dangerousness: A review and an empirical approach. British Journal of Social Work. 2001;31:249–269. [Google Scholar]

- Trocmé N, Knoke D, Fallon B, MacLaurin B. Differentiating between substantiated, suspected, and unsubstantiated maltreatment in Canada. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14:4–16. doi: 10.1177/1077559508318393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment 2011. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment.

- Winefield HR, Bradley PW. Substantiation of reported child abuse or neglect: Predictors and implications. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1992;16:661–171. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(92)90104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie H, Hur K, McHugo G. Using random-effects zero inflated Poisson model to analyze longitudinal count data with extra zeros. Paper presented at the 53rd Session of the International Statistical Institute; Seoul, South Korea. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Yampolskaya S, Banks SM. An assessment of the extent of child maltreatment using administrative databases. Assessment. 2006;13:342–355. doi: 10.1177/1073191106290607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang KY, Albert PS. Models for longitudinal data: A generalized estimating equation approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:1049–1060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]