Abstract

India ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Person with Disabilities (UNCRPD) in 2007. This is a welcome step towards realizing the rights of the persons with disability. The UNCRPD proclaims that disability results from interaction of impairments with attitudinal and environmental barriers which hinders full and active participation in society on an equal basis with others. Further, the convention also mandates the signatory governments to change their local laws, to identify and eliminate obstacles and barriers and to comply with the terms of the UNCRPD in order to protect the rights of the person with disabilities, hence the amendments of the national laws. Hence, the Government of India drafted two important bill the Right of Persons with Disabilities Bill, 2014 (RPWD Bill, 2014) and Mental Health Care Bill, 2013 (MHC Bill, 2013). There is no doubt that persons with mental illness are stigmatized and discriminated across the civil societies, which hinders full and active participation in society. This situation becomes worse with regard to providing mental health care, rehabilitation and social welfare measures to persons with mental illness. There is an urgent need to address this issue of attitudinal barrier so that the rights of persons with mental illness is upheld. Hence, this article discusses shortcomings in the Right of Persons with Disabilities Bill, 2014 (RPWD Bill, 2014) from the perspective of persons with mental illness. Further, the article highlights the need to synchronize both the RPWD Bill, 2014 and Mental Health Care Bill, 2013 to provide justice for persons with mental illness.

Keywords: Disability, persons with disability, persons with mental illness, right of persons with disabilities

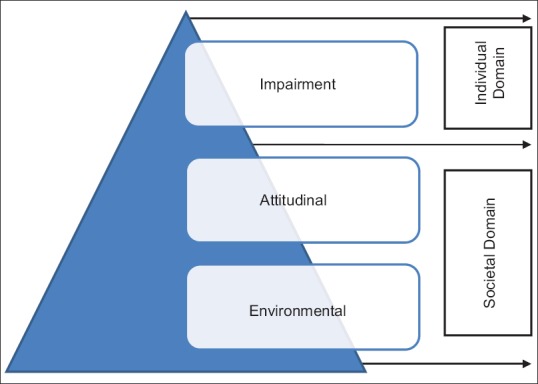

The first ever world report on disability, produced jointly by the World Health Organization and the World Bank, suggests that more than a billion people in the world today experience disability.[1] This report highlights the very fact that people with impairment face disability largely because of lack of services available to them in the society and the attitudinal and environmental barriers they face in their everyday lives add multifold to this problem as shown in Figure 1.[1]

Figure 1.

The pyramid of disability. This pyramid has three main components. While the individual “impairment” is quiet obvious, most people remain oblivious to the attitudinal and environmental barriers contributed by the society, which is larger and unfortunately forms the base of the pyramid. The interaction of the above factors contributes to disability of a person

The United Nations general assembly adopted a landmark treaty on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in December 2006. The preamble (e) to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (UNCRPD)[2] acknowledges that “Disability” is an evolving, dynamic, and complex phenomenon. Disability results from the interaction between persons with impairments and attitudinal and environmental barriers that hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others. There is no doubt that attitudes, rather than resource constraints, often create the strongest barriers in ensuring the rights of the person.[1]

This convention makes a paradigm shift from “charity-based” approach to “rights-based” approach for persons with disability, thus the dawn of a new era.[3] The scope and coverage of the convention is vast and recognizes unequivocally the rights of people with disabilities to dignity, to live in the community, to exercise their legal capacity, and to ensure their full and equal enjoyment of the rights recognized in the convention. The UNCRPD mandates to change the existing laws to bring them in conformity with the principles of the Convention. The ratification of the Convention of Rights of Persons with Disability (CRPD) in October 2007[4,5] and also national level amendments into the Protection of Human Rights Act of 1993 have also led to the broader concept of human rights which is enforceable in Indian judiciary [3,5,6] has mandated the need for amendments into Persons with Disability Act, 1995 and Mental Health Act, 1987.

Stigmatization of people with mental illness has persisted throughout history and it continues to prevail in the present civilized world.[7] People with mental disorders are, or can be, particularly vulnerable to abuse and violation of their rights.[7] Legislation is an important mechanism to ensure appropriate, adequate, timely, and humane health-care services. It also helps in protection of human rights of the disadvantaged, marginalized, and vulnerable citizens.[7,8] This article discusses shortcomings in the Right of Persons with Disabilities Bill, 2014 (RPWD Bill, 2014) from the perspective of persons with mental illness. Further, the article highlights the need to synchronize both the RPWD Bill, 2014 and Mental Health Care Bill, 2013 (MHC Bill, 2013) to provide justice for persons with mental illness.

DISABILITY AND MENTAL ILLNESS

Disability is often discussed from either the medical model or from the social model.[1] The medical model of disability views disability as a “problem” that belongs to the disabled individual solely because of their “impairment” in physical or psychological or physiological or anatomical functioning. It is not seen as an issue to concern anyone other than the individual affected.[1] However, the social model of disability, in contrast, draws on the idea that it is the society that disables people because of the attitudinal and environmental barriers.[1,9] With regard to mental illness, neither of the models fits very well but the mixed model seems to be appropriate. The medical (biological) model indicates that mental disorder is caused by “neuro-hormonal imbalance or neuro-developmental” in origin leading to subsequent impairment. Social model will be able to explain the challenges encountered because of attitude and environmental barriers, hence the model proposed “bio-psycho-social” model [1] of disability for persons with mental illness.

Mental disorders account for five of the ten leading causes of disability; they are major depression, alcohol dependence, schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD).[10] Only few developed countries such as Australia, Canada, the US, the UK, and so forth have recognized this and are proactive in providing social welfare measures for persons with mental illness. Although legislations in these countries have ensured the social welfare schemes for persons with mental illness, they continue to be underdiagnosed, underestimated in official statistics, discriminated, and face various challenges during the assessment of disability.[11] This situation becomes worse with regard to providing care and social welfare measures to persons with mental illness in the low- and middle-income countries.[12] Further, on comparing functional disability of mental disorders with physical disorders, it was found that mental disorders are associated with a similar or higher negative impact on daily functioning than arthritis and heart disease.[13]

Persons with mental illness face significant challenges during the assessment of disability due to the following reasons: (a) Mental disability cannot be seen,[11] hence it is often called “invisible disability” and at the same time they look normal in contrast to physical disability, (b) mental illness are difficult to diagnose through an objective laboratory instrument, (c) signs and symptoms of mental illness are often difficult to qualify and quantify, (d) mental illness are fluctuating, episodic, and dynamic in nature, (e) persons with mental illness often find it difficult to communicate their challenges faced in day-to-day life, (f) myths of mental illness prevailing within the society can deny their rights, (g) providing early and adequate treatment can reduce disability considerably in certain cases, and (h) the nonavailability of simple, comprehensive, and highly reliable instruments to measure disability. Owing to the above challenges, various countries have adopted certain mechanisms such as need for documentation of illness for certain duration, adequate treatment needs to be given, minimum duration of illness, frequent assessment, not been able to earn at least “X” number of dollars per month in the past 6 months and so forth. These safeguards are required so that public funds are not misused.

IMPAIRMENT IN MENTAL ILLNESS

Article 1 of the UNCRPD clearly states that persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments, which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.[2] Mental illness causes substantial impairment, and a dose–response relationship has been established between the severity of mental illness and disability.[14,15] Persons with mental illness are more likely to experience economic and social disadvantage than those without disability.[16,17] All the evidence clearly indicates that people who experience mental health conditions or intellectual impairments appear to be more disadvantaged in many settings than those who experience physical or sensory impairments.[16,18] There has been a pattern of prejudice against mentally disabled individuals that keeps them far away from receiving equal treatment under the law.[19]

Major mental disorders are characterized by a chronic and relapsing course with generally incomplete remissions, substantial functional decline, frequent psychiatric and medical comorbidities, and increased mortality.[20,21,22,23] Mental illness does affect various domains of the brain functioning such as cognitive functions, emotional, behavioral aspects, energy and drive, psycho-motor activity, self-esteem, biological functioning, employment, activities of daily living, social skills, help-seeking behavior, health in general, and so forth.[17,22,24,25,26]

The World Health Organization has discussed the above issues in an International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF). As per the ICF, there are three domains as follows: (a) Body functions and structures, (b) activity limitations and participation restriction, and (c) environmental factors.[27] The relevant areas for function and disability known to affect in mental illness are as follows: (a) Body functions and structures domain are mental functions, sensory functions, voice and speech functions, (b) activity limitations and participation restriction domain are learning and applying knowledge, general tasks and demand, communication, mobility, self-care, domestic life, interpersonal interactions and relationships, major life areas, and community, social, and civic life, and (c) environmental factors-support and relationships, attitudes, services, and policies.[27]

Disability is very well established in mental retardation,[28] schizophrenia,[29,30] anxiety disorders,[31,32] OCD,[33] mood disorders,[34] depression,[35,36] dementia,[37] posttraumatic stress disorder,[38] and substance use disorders.[39,40,41] There have been strong debates across the world whether substance use disorders, personality disorders, and gender identity disorder should be considered for disability benefits.

In developed countries (such as Canada, the US, and so forth), although alcohol and drug addiction often substantially impairs a person's ability to work, an applicant will not be approved for disability on the basis of the drug addiction alone, however if the applicant can prove that because of substance use, he/she has developed irreversible medical or mental problems, he/she can get the approval for welfare benefits. Further, the welfare measures can be made contingent upon attending treatment for drug addiction/rehabilitation, and welfare benefits will be transferred to a representative payee (usually family members), who is expected to prevent the persons with mental illness (substance user) from spending the money on drugs and manage applicants' expenses from the disability pension. There is no doubt that mental illness including substance use significantly interferes with the performance of major life activities, such as learning, working, socializing, interacting, communicating, and participating with others, the issue revolves around, how a civilized society can be inclusive and nondiscriminatory.

ATTITUDINAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL BARRIERS

Mental illness can have a devastating impact on any family especially when the primary bread winner suffers from the illness. Persons with mental illness drift to poverty adding to the suffering which is a double disadvantage.[3,42] Adding to this societal myths, discrimination,[43] stigma,[44,45] human rights violation,[12,46] and nonprovision of basic access to MHC facilities [47] can add significant burden to the society, family, and also on the persons with mental illness.[43,44,48] The discrimination is no doubt a basic human rights violation under the United Nation's International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, and CRPD.[12] Stigma and discrimination lead to pervasive human rights violations against people with mental and psychosocial disabilities in low- and middle-income countries.[12] Mentally ill patients continue to face discrimination at all levels compared to those with only physical disabilities. Many patients are deprived of disability benefits because of simple ignorance by the politicians, policy makers, and executive (implementing) authorities.[3] The discriminative practice becomes more evident, when persons with mental illness approach for employment. The policy makers and experts on one hand acknowledge the disability due to mental illness, and on the other, they also hold the opinion that they will not be able to do anything, if the job is given to them. Even the Persons with Disability Act, 1995 does not have any reservations earmarked for mental disability. The Persons with Disability Act, 1995 needs amendments to do justice to people with mental illness otherwise, the act itself becomes a source of discrimination.[3]

The draft version of the RPWD Bill, 2014, has included mental illness, advocates for nondiscriminatory practices, and also reserves employment for persons with mental illness. However, considering the amount of attitudinal and environmental barriers faced by the persons with mental illness, there should have been special emphasis and social welfare measures to bring them into mainstream. The term stigma refers to “a social devaluation of a person.”[49] The stigma significantly contributes to social isolation, distress, and difficulties in employment faced by sufferers.[50] Even though the mental health professionals join hand in enhancing stigma on persons with mental illness, many mental health professionals argue and refuse to provide disability certificate for people with substance dependence syndrome, somatoform disorders, anxiety disorders, selective learning deficits, attention deficit hyperactive disorder, personality disorders, autism, and so forth. Mental health professionals need to know that disability certificate is not based on the diagnosis, but on the amount of disability experienced by the individual. Regarding this issue, policy makers in India have thought beyond the conventional way and included all mental illnesses for disability assessment and benefit.[3] There is also a need to identify certain jobs and reserve them for persons with mental illness. Now, it is high time for mental health professionals to wake up and defend the rights of persons with mental illness.

In a country like India, MHC is usually not perceived as an important aspect of public health care [3] and above this, in the current global financial crisis, people with mental disorders are among the most vulnerable, and programs for their social inclusion are not always regarded as a priority by local administrators.[48] Lack of mental health care facilities at the primary health care level, have resulted in government mental hospitals becoming a dumping ground. Non-existences of rehabilitation centers for persons with mental illness and lack of investment in mental health care by the government clearly indicates the plight of persons with mental illness within the civil society. This gross apathy and neglect must be the main target for advocacy by mental health professionals across nationwide.[48] There are studies which support the call to invest and scale up MHC, not only as a public health and human rights priority, but also as an economic development priority for the nation.[51]

THE RIGHTS OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITY BILL, 2014

By ratifying the UNCRPD in 2007, India took on a series of obligations to transform the treatment of persons with disabilities from being objects of charity to subjects with rights who can claim those rights. Hence, the Government of India has drafted Rights of Persons with Disabilities Bill, 2014 introduced by the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment and a draft of MHC Bill, 2013, which is prepared by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, is pending in the parliament for approval. No doubt both bills are better than their predecessors but they need to be fine-tuned to cater to the need of the persons with mental illness. This section focuses on the shortcomings and possible remedies from a mental illness and mental disability perspective.

The definition

The Clause 2(q) of the RPWD Bill, 2014 discusses the definition of “persons with disabilities.” It is defined as any person with long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairment, which may hinder his/her full and effective participation in society equally with others. Unfortunately, according to the Bill, this “long term” is not defined. At the same time, the course of mental illness is known to be episodic in nature with devastating effect, and hence this term can be used to deny much needed social welfare measures to the needy.

Measures to counteract stigma and discrimination

The UNCRPD convention prohibits all forms of discrimination against persons with disabilities. The convention not only ensures equality for people with disabilities, but also moves forward in accommodating people's differences which is the essence of substantive equality, and this understanding is especially a key to eliminating discrimination against persons with disabilities suffering from mental illness. In this regard, the persons with mental illness are stigmatized and discriminated more when compared to physically disabled, hence special accommodative measures need to be made available proactively in the Rights of the Persons with Disability Bill, 2014. It is high time that the society “honors” but do not “ignore” the rights of the persons with mental illness. For example, the policy makers take proactive steps by identifying certain jobs and reserve them for persons with mental illness, disability pension, rehabilitation, free health care, housing, and so forth.

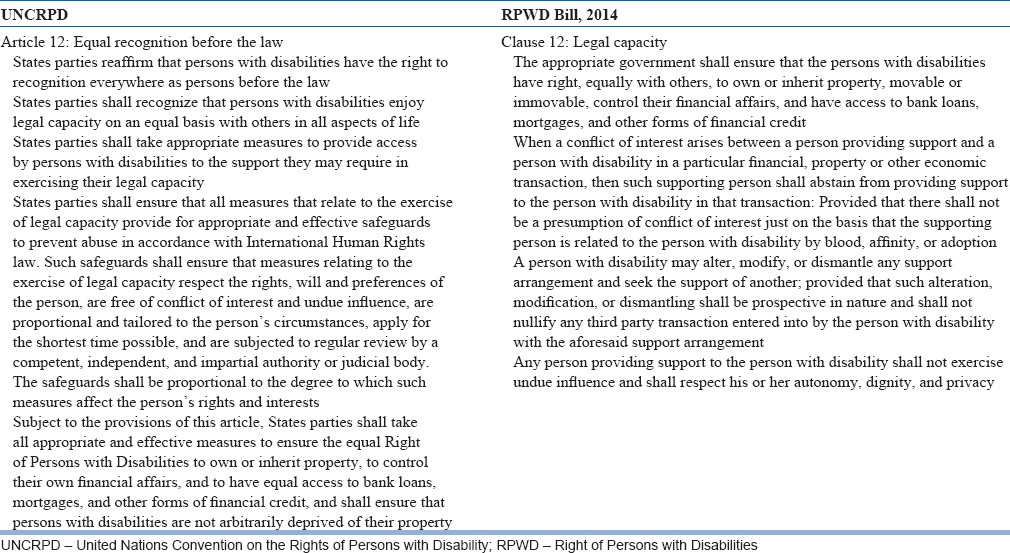

Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability

Equal recognition before the law is an important article for persons with disability [Table 1] and also a controversial issue for persons with mental illness under the UNCRPD. Unfortunately, the same issue is reduced to “Legal Capacity” in Clause 12 of the RPWD Bill, 2014 [Table 1]. This contentious clause of the Bill is reduced to an “all or none” phenomenon, which is detrimental to persons with mental illness. Every person requires assistance or help in making decisions (for example, any person planning to a buy a car, requires assistance in the form of information, opinion, loan, review from various sources, and so forth). As per the RPWD Bill, 2014, one has to approach the court for appointing a guardianship for getting assistance (mentioned in Clause 13 of the Bill).

Table 1.

Comparing article 12 of United Nations of Convention of Rights of Persons with Disability and Clause 12 of Right of Persons with Disabilities Bill, 2014

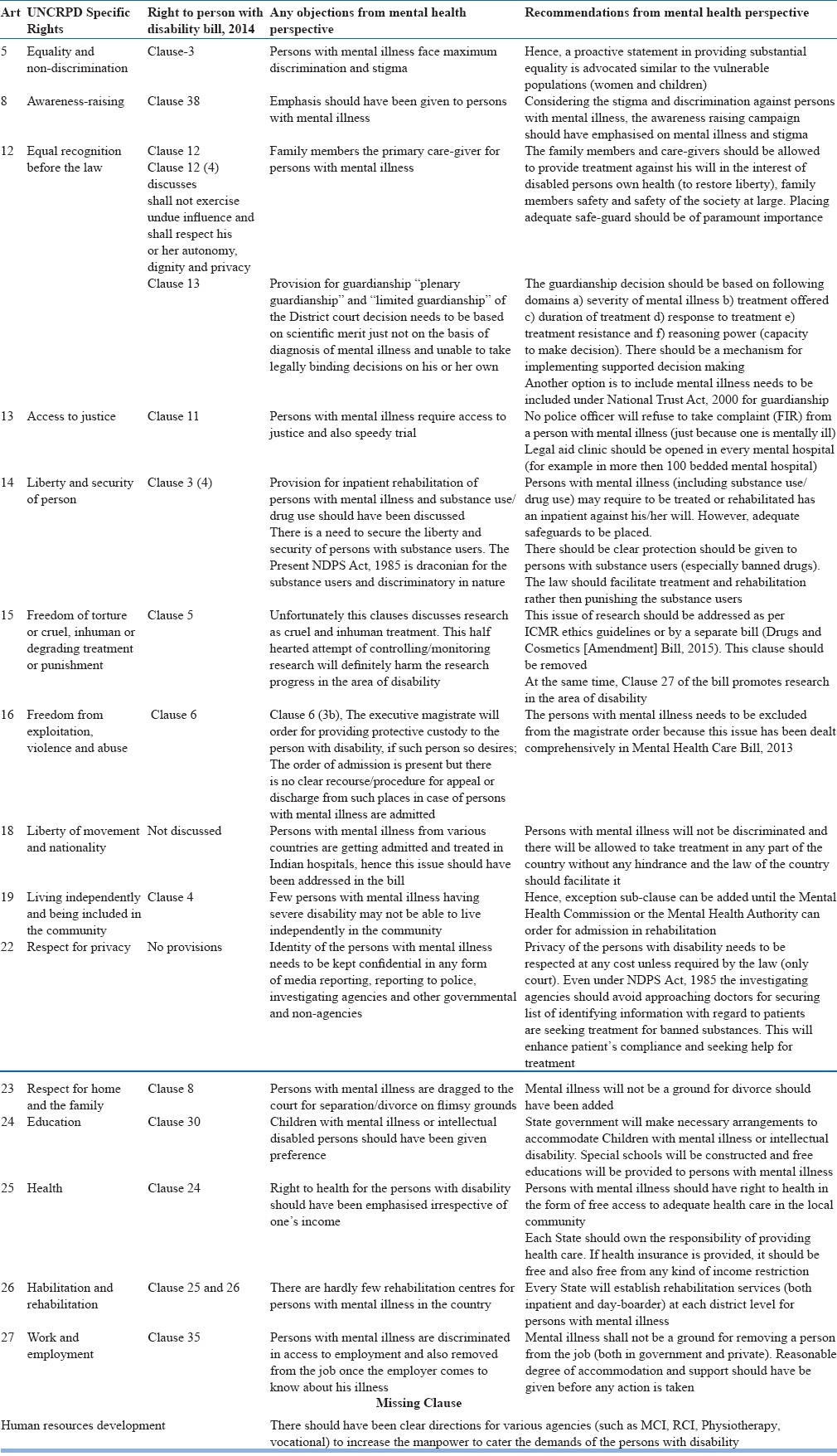

The RPWD Bill, 2014 discusses appointing of “plenary” and “limited” guardianship in Clause 13. The Bill should have discussed about the assisted decision-making for people with mental illness rather than just legalizing the process of guardianship through the District Court. This clause is not in the interest of protecting the rights of the persons with mental illness. It would be appropriate to include persons with mental illness under the National Trust Act, 2000 for guardianship or else needs to modify to accommodate “assisted decision making.” There are many such clauses in RPWD Bill, 2014 that needs to be modified to accommodate the spirit of UNCRPD from the perspective of persons with mental illness. These clauses are mentioned in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of convention on rights of persons with disabilities 2006 (CRPD) and the rights of persons with disabilities bill, 2014 (RPWD bill, 2014)

SYNCHRONIZING MENTAL HEALTH CARE BILL, 2013, AND RIGHT OF PERSONS WITH DISABILITIES BILL, 2014

There is an urgent need to synchronize MHC Bill, 2013 and RPWD, Bill 2014, so that the rights of the persons with mental illness are upheld. For example, Clause 98 and 99 of RPWD Bill, 2014, discusses the formation of Special Court and also appointing of Special Public Prosecutor for the purpose of implementation of the legislation. Similarly, Clause 73 of the MHC Bill, 2013 discusses having the Central Mental Health Commission and Mental Health Review Boards at each District for providing justice to the persons with mental illness. This is a duplication of services. Synchronizing both bills would help share the resources and can enable implementation of both the bills effectively.

Another example is that Clause 24(a) of the RPWD Bill, 2014 discusses health care and proposes that free health care in the vicinity, especially in rural areas subject to such family income as may be notified. However, Clause 18 of the MHC Bill, 2013 discusses right to access MHC, which proactively talks about “right to access MHC” as every person shall have a right to access MHC and treatment from mental health services run or funded by the appropriate government. This difference between RPWD Bill, 2014 (health care, subject to such family income) and MHC Bill, 2013 (every person shall have a right to access MHC) without any income limitation is the real empowerment of the persons with disability. The main reason for the above argument is persons with mental illness do need physical health care because of higher prevalence of physical morbidity, hence all physical health care also should be made available free. Further, Clause 25 and 26 of the RPWD Bill, 2014 discusses about the insurance schemes for health and rehabilitation. Unfortunately, the Bill endorses that “State authorities shall do this within their economic capacity and development.” This is against the idea of providing “Rights” and allowing the “State” to absolve from their duties.

Another example is Clause 4[1] of the RPWD Bill, 2014, which mandates that the persons with disabilities shall have the right to live in the community. However, the persons with severe mental illness may not be able to stay in the community because of their symptoms. Hence, such patients who are severely ill or with severe intellectual disability should be allowed to be stay in the rehabilitation centers even against their will to provide adequate care and also keeping the larger interest of the society. Hence, both the bills need to be synchronized for providing justice.

To conclude, the UNCRPD is a welcome step toward realizing the rights of the persons with disability. India ratified the UNCRPD in 2007, which has casted obligation to modify national laws. The Government of India being one of the signatories has drafted two important bills, namely RPWD Bill, 2014, and MHC Bill, 2013. However, there are several shortcomings in both the bills. If the RPWD Bill 2014 and the MHC Bill, 2013 are passed in the present form, it would be against the spirit of the UNCRPD. It also fails to acknowledge that persons with mental illness do undergo severe attitudinal barriers such as stigma and discrimination, many of which are created by the societal environment. There is also an urgent need to synchronize the RPWD Bill, 2014 and the MHC Bill, 2013 for providing justice to persons with mental illness. Further, there is an urgent need to educate people.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. World Report on Disability. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNCRPD. United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. 2006. [Last accessed on 2016 Jan 28]. Available from: http://www2.ohchr.org/english/law/disabilities-convention.htm .

- 3.Math SB, Nirmala MC. Stigma haunts persons with mental illness who seek relief as per Disability Act 1995. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:128–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.CRPD. Convention on Rights of Persons with Disability (CRPD) [Last accessed on 2016 Feb 04]. Available from: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/CRPD/Pages/Convention.aspx .

- 5.Math SB, Murthy P, Chandrashekar CR. Mental health act (1987): Need for a paradigm shift from custodial to community care. Indian J Med Res. 2011;133:246–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NHRC. National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) [Last accessed on 2016 Feb 04]. Available from: http://www.nhrc.nic.in/

- 7.Math SB, Nagaraja D. Mental health legislation: An Indian perspective. In: Murthy P, Nagaraja D, editors. Mental Health; Human Rights. Bangalore, New Delhi: National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, National Human Rights Commission; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. WHO Resource Book on Mental Health, Human Rights and Legislation. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shakespeare T. The Disability Studies Reader. Vol. 2. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group; 2006. The social model of disability; pp. 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Boston: Harvard School of Public Health on behalf of the World Health Organization and the World Bank; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mykletun A, Overland S, Dahl AA, Krokstad S, Bjerkeset O, Glozier N, et al. A population-based cohort study of the effect of common mental disorders on disability pension awards. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1412–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.8.1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drew N, Funk M, Tang S, Lamichhane J, Chávez E, Katontoka S, et al. Human rights violations of people with mental and psychosocial disabilities: An unresolved global crisis. Lancet. 2011;378:1664–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61458-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buist-Bouwman MA, De Graaf R, Vollebergh WA, Alonso J, Bruffaerts R, Ormel J. ESEMeD/MHEDEA Investigators. Functional disability of mental disorders and comparison with physical disorders: A study among the general population of six European countries. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113:492–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, Gasquet I, Kovess V, Lepine JP, et al. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291:2581–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goetzel RZ, Long SR, Ozminkowski RJ, Hawkins K, Wang S, Lynch W. Health, absence, disability, and presenteeism cost estimates of certain physical and mental health conditions affecting US employers. J Occup Environ Med. 2004;46:398–412. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000121151.40413.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sen A. The Idea of Justice. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Insel TR. Assessing the economic costs of serious mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:663–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08030366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roulstone A, Barnes C. Working Futures: Disabled People, Employment and Social Inclusion. Bristol: Policy Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perlin ML. The Hidden Prejudice: Mental Disability on Trial. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barker PR, Manderscheid RW, Hendershot GE, Jack SS, Schoenborn CA, Goldstrom I. Serious mental illness and disability in the adult household population: United States, 1989. Adv Data. 1992;218:1–11. doi: 10.1037/e608882007-001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drake RE, Skinner JS, Bond GR, Goldman HH. Social security and mental illness: Reducing disability with supported employment. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28:761–70. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Üstün TB, Sartorius N. Mental Illness in General Health Care: An International Study. New York: John Wiley &; Sons; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanderson K, Andrews G. Prevalence and severity of mental health-related disability and relationship to diagnosis. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:80–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, Hadley TR. Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:565–73. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stuart H. Mental illness and employment discrimination. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19:522–6. doi: 10.1097/01.yco.0000238482.27270.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim D, Sanderson K, Andrews G. Lost productivity among full-time workers with mental disorders. J Ment Health Policy Econ. 2000;3:139–146. doi: 10.1002/mhp.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ustün TB, Chatterji S, Kostansjek N, Bickenbach J. WHO's ICF and functional status information in health records. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;24:77–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan VA, Leonard H, Bourke J, Jablensky A. Intellectual disability co-occurring with schizophrenia and other psychiatric illness: Population-based study. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:364–72. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.044461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosen A, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Parker G. The life skills profile: A measure assessing function and disability in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1989;15:325–37. doi: 10.1093/schbul/15.2.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper J, Bostock J. Handbook of Social Psychiatry. London: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1988. Relationship between schizophrenia, social disability, symptoms and diagnosis; pp. 317–30. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hendriks SM, Spijker J, Licht CM, Beekman AT, Hardeveld F, de Graaf R, et al. Disability in anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord. 2014;166:227–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leon AC, Portera L, Weissman MM. The social costs of anxiety disorders. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1995;27:19–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gururaj GP, Math SB, Reddy JY, Chandrashekar CR. Family burden, quality of life and disability in obsessive compulsive disorder: An Indian perspective. J Postgrad Med. 2008;54:91–7. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.40773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon GE. Social and economic burden of mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:208–15. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruce ML. Depression and disability. In: Williamson GM, Shaffer DR, Parmelee PA, editors. Physical Illness and Depression in Older Adults: A handbook of Theory, Research and Practice. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2002. pp. 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Zeller PJ, Paulus M, Leon AC, Maser JD, et al. Psychosocial disability during the long-term course of unipolar major depressive disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:375–80. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.4.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di Bari M, Pahor M, Franse LV, Shorr RI, Wan JY, Ferrucci L, et al. Dementia and disability outcomes in large hypertension trials: Lessons learned from the systolic hypertension in the elderly program (SHEP) trial. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:72–8. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Frueh BC, Elhai JD, Gold PB, Monnier J, Magruder KM, Keane TM, et al. Disability compensation seeking among veterans evaluated for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54:84–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.1.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Compton WM, Thomas YF, Stinson FS, Grant BF. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:566–76. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, Baxter AJ, Ferrari AJ, Erskine HE, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1575–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Degenhardt L, Whiteford HA, Ferrari AJ, Baxter AJ, Charlson FJ, Hall WD, et al. Global burden of disease attributable to illicit drug use and dependence: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet. 2013;382:1564–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61530-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel V, Kleinman A. Poverty and common mental disorders in developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:609–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thornicroft G, Brohan E, Rose D, Sartorius N, Leese M INDIGO Study Group. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination against people with schizophrenia: A cross-sectional survey. Lancet. 2009;373:408–15. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koschorke M, Padmavati R, Kumar S, Cohen A, Weiss HA, Chatterjee S, et al. Experiences of stigma and discrimination of people with schizophrenia in India. Soc Sci Med. 2014;123:149–59. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sartorius N. Stigma and mental health. Lancet. 2007;370:810–1. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gostin LO, Gable L. The human rights of persons with mental disabilities: A global perspective on the application of human rights principles to mental health. MD Law Rev. 2004;63:20–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saxena S, Thornicroft G, Knapp M, Whiteford H. Resources for mental health: Scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet. 2007;370:878–89. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maj M. The rights of people with mental disorders: WPA perspective. Lancet. 2011;378:1534–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60745-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thara R, Srinivasan TN. How stigmatising is schizophrenia in India? Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2000;46:135–41. doi: 10.1177/002076400004600206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crisp AH, Gelder MG, Rix S, Meltzer HI, Rowlands OJ. Stigmatisation of people with mental illnesses. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:4–7. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lund C, De Silva M, Plagerson S, Cooper S, Chisholm D, Das J, et al. Poverty and mental disorders: Breaking the cycle in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2011;378:1502–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60754-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]