Abstract

Background:

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a severe form of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) characterized by mood changes, anxiety, and somatic symptoms experienced during the specific time of menstrual cycle. Prevalence data of PMS and PMDD is sparse among college girls in India.

Aims:

The aim of this study is to study the prevalence of PMS and PMDD among college students of Bhavnagar (Gujarat), its associated demographic and menstrual factors, to rank common symptoms and compare premenstrual symptom screening tool (PSST) with Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR defined PMDD (SCID-PMDD) for sensitivity and specificity.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional survey was done in five colleges of Bhavnagar. Of 529 subjects approached, 489 college girls were finally analyzed for sociodemographic data, menstrual history, and PSST. SCID-PMDD was applied among those who were positive on PSST and 20% of those who were negative. The data were analyzed using OpenEpi Version 2. Chi-square test was done for qualitative variables and analysis of variance for quantitative variables. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values were calculated for PSST.

Results:

The prevalence of PMS was 18.4%. Moderate to severe PMS was 14.7% and PMDD was 3.7% according to DSM IV-TR and 91% according to International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition criteria. The symptoms commonly reported were “fatigue/lack of energy,” “decrease interest in work,” and “anger/irritability.” The most common functional impairment item was “school/work efficiency and productivity.” PSST has 90.9% sensitivity, 57.01% specificity, and 97.01% predictive value of negative test.

Conclusion:

Prevalence of PMS among college students is similar to other studies from Asia. PSST is a useful screening tool for PMS, and it should be confirmed by more specific tool as by SCID-PMDD. Routine screening with PSST can identify college girls who can improve with treatment.

Keywords: Premenstrual dysphoric disorder, premenstrual syndrome, premenstrual symptom screening tool, structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR-premenstrual dysphoric disorder

INTRODUCTION

According to World Health Organization, sadness, loss of confidence, low self-esteem, and less energy are more common among females.[1] In India, about one-fourth (27.7%) of the female population falls in the 15-29 years age-group.[2] This age is a transition phase of life associated with spurt of physical, mental, emotional, and social development.

Some degrees of premenstrual problems are experienced especially in the initial years of reproductive life by majority of young women. Epidemiologic surveys have estimated that as many as 80% of women of reproductive age experience some symptoms attributed to the premenstrual phase of the menstrual cycle.[3]

Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is the severe form of premenstrual syndrome (PMS). The psychological symptoms are irritability, emotional lability, anxiety, and depression. Somatic symptoms include edema, weight gain, mastalgia, headache, syncope, and paresthesia. They appear about 1 week before the onset of menses and disappear soon after onset of menses.[4]

The morbidity associated with PMS is because of severity of symptoms, chronicity, the resulting emotional distress or impairment in work, relationships, and activities. The level of impairment of PMS is significantly higher than community norms on assessment by standard measures and similar to that of major depression. Women with PMS report significant impairment in personal relationships, compromised work levels and increased absence from work, school, or college.[5] There are very few studies assessing PMDD in young girls.[6]

We considered that PMS is relatively under-investigated area of psychiatry in India; hence, this study was planned. The objectives of the study are to find the prevalence of PMS and PMDD among college students of Bhavnagar (Gujarat), study its associated demographic and menstrual factors, rank common premenstrual symptoms, and compare premenstrual symptom screening tool (PSST) with Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR defined PMDD (SCID-PMDD) for sensitivity and specificity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Government Medical College Bhavnagar. A cross-sectional study was done among undergraduate students of five colleges of Bhavnagar city (Gujarat) including Government Nursing College, Excel School of Nursing, Shree Sahajan and Institute of Nursing, Mahila Arts and Commerce College, and Government Medical College Bhavnagar from January to August, 2012.

The study sample comprised 529 college girls, and convenient sampling method was used. The sample size was calculated using the OpenEpi Version 2 (Atlanta, GA, USA) open source epidemiological calculator with hypothesized 15% ± 4% prevalence of PMS and PMDD at 99% confidence level. The design effect was kept one. The minimal sample size which came on estimation at 95% confidence level was 307. College students of 17–30 years, having regular menstrual cycles (21–35 days) and willing to give written informed consent, were invited to participate in the study. Those who could not participate in the research due to medical and gynecological illnesses such as anemia, diabetes, hypothyroidism, asthma, migraine, epilepsy, pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, and amenorrhea were excluded.

Premenstrual symptoms screening tool

It is the screening tool developed by Steiner et al.,[3] which reflects and “translates” categorical DSM-IV-TR criteria [7] into a rating scale with degrees of severity. It includes 14 items assessing premenstrual symptoms of mood, anxiety, sleep, appetite, and physical symptoms. It also includes functional impairment items of five different domains. Participants rated their experience of each symptom and functional impairment item on four-point Likert scale as “not at all,” “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe” in last 12 months duration during most of the cycles. “PMDD,” “moderate to severe PMS,” and “no/mild PMS” subjects were identified using PSST scoring criteria.[3] PSST was forward translated in the vernacular language (Gujarati) using standard dictionaries. The translation was validated by back translation and comparison with original form by group of experts who were well-versed with both languages. Gujarati version was used for nursing, arts, and commerce stream. Original English version was used for medical students.

Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR defined premenstrual dysphoric disorder

SCID-PMDD is a clinician-administered structured interview developed and validated by Accortt et al.[8] It includes 11 psychological and physical symptoms of criterion A [7] phrased in a detailed layperson format similar to items on the SCID [9] to facilitate the assessment of the specific DSM-IV-TR criteria for PMDD.

The case record form of the study had three sections. Section I included the demographic data and activity levels. Section II included menstrual history, premenstrual symptoms, hormonal pills use, and family history of PMS symptoms in first-degree relatives. Section III included PSST.[3]

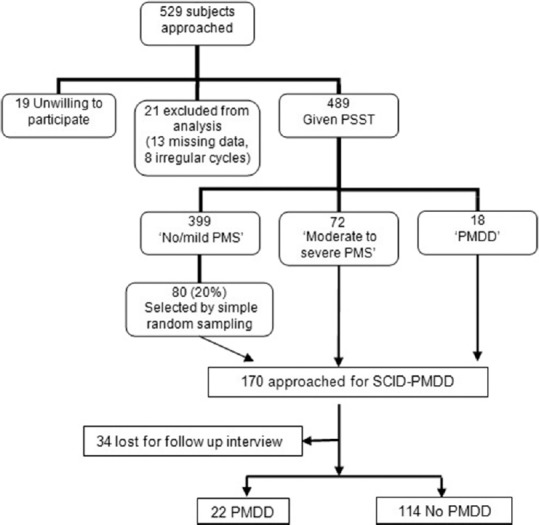

A total of 529 participants were approached. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant after explaining the objectives and procedure of the study. The questions and meaning of related terms were explained to the participants up to their satisfaction. Case record forms were filled in the classrooms under supervision of investigator. Confidentiality was assured to all the participants ensuring cooperation and participation. The research methodology is shown in Figure 1. Structured clinical interview was conducted in the presence of female attendant. Total 170 participants including all moderate to severe PMS and PMDD group and 80 participants (20% of no/mild PMS group) were called for the structured clinical interview for PMDD (SCID-PMDD) according to the DSM-IV-TR criteria. Thirty-four participants did not come for the interview (80% response rate for structured interview).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of research methodology

The data was analyzed with OpenEpi Version 2 open source calculator. Data was expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and percentage for categorical variables. Prevalence of PMS and PMDD according to DSM-IV-TR research criteria was calculated. Prevalence of premenstrual tension syndrome according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10) criteria was also calculated. Chi-square test was used for qualitative variables to find the significance of difference between proportion among respective groups: “No/mild PMS,” “moderate to severe PMS,” and “PMDD.” Analysis of variance test with post hoc analysis (Kruskal–Wallis test) was used to find out the significance of difference between the means of respective groups with Graph pad InStat version 3.06 (GraphPad Software Inc.). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. PSST was compared with SCID-PMDD between “moderate to severe PMS and PMDD” versus “no/mild PMS” group in terms of sensitivity and specificity. Predictive values of positive test and negative test were calculated for PSST.

RESULTS

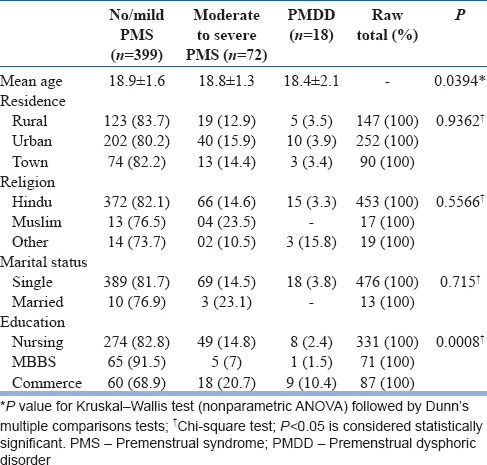

As shown in Figure 1, total 529 subjects were approached. The mean age of all participants was 18.9 ± 1.6 years. PMDD is associated with relatively young age group as compared to no/mild PMS. There was no statistically significant difference among three groups with respect to residence, religion, and marital status. Commerce students had higher rates of PMS and PMDD compared to nursing and MBBS students [Table 1].

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants

On screening by PSST, 18 participants (3.7%) met the DSM-IV-TR criteria for the diagnosis of PMDD. Seventy-two participants (14.7%) marginally missed the DSM-IV TR criteria for the diagnosis of PMDD. Hence, they were identified as “moderate to severe PMS.” Remaining 399 participants (81.6%) experienced “no/mild PMS.”

According to ICD-10,[10] 91.4% participants (n = 447) had, at least, one premenstrual symptom of any given severity (mild to severe) in at least more than or equal to half of the menstrual cycles during last 12 months duration. They were identified as having premenstrual tension syndrome according to ICD-10. Forty-two participants (8.6%) reported no symptoms.

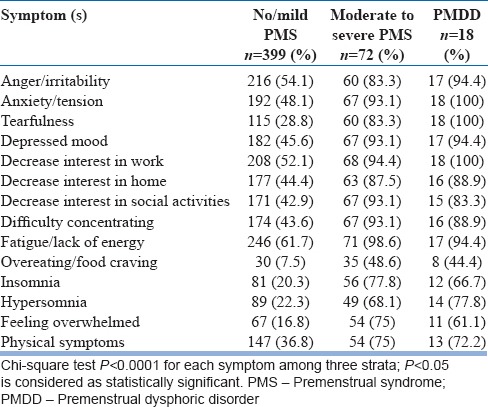

The most commonly reported symptom was “fatigue/lack of energy” (68.3%), followed by “decrease interest in work” (60.1%) and “anger/irritability” (59.9%). Almost all participants (98.6%) of “moderate to severe PMS” group and majority of PMDD group (94.4%) reported “fatigue/lack of energy” as moderate to severe. All participants of PMDD group and majority of “moderate to severe PMS” group (94.4%), and near two-third of all (60.1%) participants reported “decrease interest in work.” It remained the second most common reported symptom.

Although “anger/irritability” remained on third rank, its overall prevalence was 59.9% which was almost similar to the prevalence of “decrease interest in work” (60.1%). More than half of “no/mild PMS” group (54.4%), 83.3% of “moderate to severe PMS” group, and large number (94.4%) of “PMDD” group reported “anger/irritability [Table 2].”

Table 2.

Frequency of premenstrual symptoms among three groups

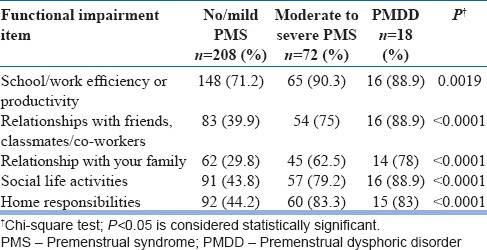

Total 298 participants reported, at least, one area of impaired functioning. Most frequent functional impairment was “school/work efficiency and productivity.” It was seen among 76.8% of the total respondents, 90.3% of “moderate to severe PMS,” and 16 of 18 among “PMDD” group [Table 3].

Table 3.

Frequency of functional impairment among groups

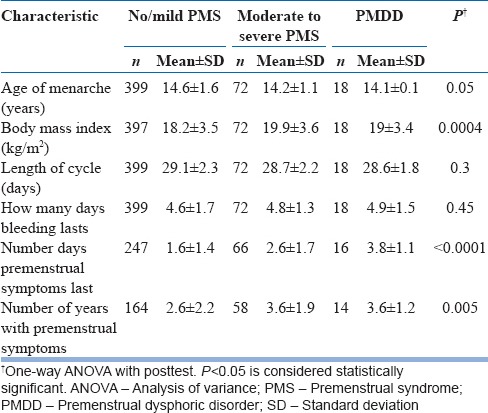

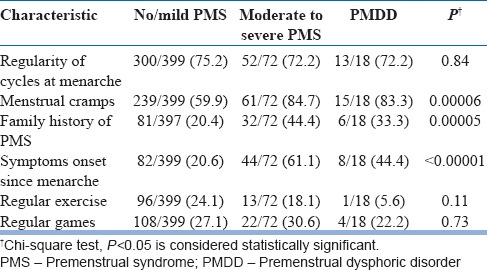

Tables 4 and 5 show the menstrual characteristics and demographic correlates among groups, respectively.

Table 4.

Menstrual correlates among three groups

Table 5.

Demographic correlates among three groups

The mean menstrual cycle length was 28.9 ± 2.3 days with mean 4.6 ± 1.6 days of bleeding. The average age of onset of menstruation was 14.3 ± 1.1 years. There was no statistically significant difference among groups with respect to age of menarche, length of the menstrual cycle, and days of the menstrual bleeding. PMDD group and “moderate to severe PMS” group experienced more number of days and years with premenstrual symptoms as compared to “no/mild PMS” group.

There was no significant difference among groups with respect to regularity of cycles at the time of menarche (P = 0.84). There was statistically significant difference among groups with respect to menstrual cramps, positive family history in first-degree relative, and symptoms onset since menarche.

More number of participants in “moderate to severe PMS” and “PMDD” groups reported that they had symptoms since menarche as compared to “no/mild PMS” group (P < 0.00001). There was no statistically significant difference among groups with respect to regular exercise (P = 0.1143) or regular games (P = 0.7316).

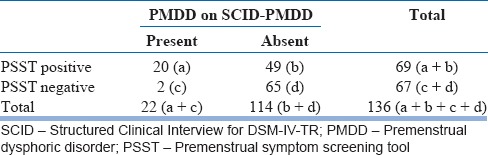

Total 20 participants were found to have PMDD according to the structured interview. Eighteen of them were from “moderate to severe PMS” group and two participants from “no/mild PMS” group. Sensitivity of PSST is 90.9%, specificity 57.01%, predictive value of positive PSST 28.98%, and predictive value of the negative PSST 97.01% [Table 6].

Table 6.

Premenstrual symptom screening tool results compared with Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR-premenstrual dysphoric disorder (n=136)

DISCUSSION

The sample of this study is comparable with previous similar studies because mean age of all participants is 18.9 ± 1.6 years and the majority of them are urban resident and unmarried. The participants from previous studies were also from similar age group college students, had urban residence, and were unmarried.[11,12,13,14,15,16]

According to DSM-IV-TR research criteria, the prevalence of PMS is 18.4% (14.7% for moderate to severe PMS and 3.7% for PMDD) among college students in our study. It is in agreement with the study done by Rapkin and Mikacich [17] and other studies from Asian countries among this population.[12,13,15,18] This finding is also consistent with literature.[19,20] The prevalence of severe PMS and PMDD in this study is not in agreement with the study by Steiner et al.[11] who reported 21.3% and 8.3%, respectively, and also differs from study by Chayachinda et al.[21] who reported 25.1% of PMDD among Thai nurses. The lower prevalence in our study can be explained by influence of cultural beliefs, socialization factors, actual experiences, and concomitant life stresses about menstruation in Indian context which affects both experiencing and reporting of the premenstrual symptoms. Banerjee et al. reported 6.4% prevalence of PMDD in Indian women.[22] The prospective study design, relatively smaller sample size (n = 62), and higher age group of that study can explain the difference of prevalence from our study.

According to ICD-10 diagnostic criteria of Premenstrual Tension Syndrome,[10] the prevalence of PMTS in our study is 91.4%. Kamat et al. reported 90%, Singh et al. reported 86%, and Tabassum et al. reported 53% among young girls according to ICD-10.[13,16,23] Bakhshani et al. reported that 98.2% had, at least, one mild to severe premenstrual symptom in their study.[12] A study done by Cleckner-Smith et al. in an adolescent sample showed that all participants (n = 78) reported, at least, one premenstrual symptom of minimal severity.[24] The prevalence rates are higher according to ICD-10 criteria as the criteria are relatively less stringent and do not require the prospective diary for confirmation of the diagnosis.

The study indicates that overall most commonly reported symptom is fatigue/lack of Energy (68.3%). Similar findings were reported in studies done by Bakhshani et al.[12] and Nourjah.[15] It was the third most common symptom reported by Tabassum et al.,[13] Nisar et al.,[18] and Pearlstein et al.[25]

Other highest reported symptoms were decreased interest in work (60.1%) and anger/irritability (59.9%) on the second and third rank, respectively. Anger/irritability has been reported as most common symptom by previous several studies.[3,11,13,18,25,26] “Decreased energy” and “being irritable” were most common reported premenstrual symptoms in a community-based nonpatient sample of 321 black and 462 white women studied by Stout et al.[27] A cross-sectional study done among Indian college students by Singh et al. reported that the most common symptom reported by subjects not having any impairment was “irritability” and those having impairment, the most common symptom was “tiredness and lack of energy.”[16] There is repositioning of symptoms in diagnostic criteria of PMDD within the revised manual of DSM-5.[28] The order of symptoms is shuffled in revised manual. Mood swings and irritability are now at the top of the list. “Markedly depressed mood” was at the top in the DSM-IV TR research criteria of PMDD. Hence, finding of this study is consistent with this context of change in DSM-5.[28]

This study reports that the most frequent functional impairment item reported was school/work efficiency and productivity (46.8%). Steiner et al. found that nearly three-quarters of the PMDD and almost half of the severe PMS cases reported symptoms interfered with their relationships with friends, classmates, and/or coworkers, and/or school/work efficiency/productivity.[11]

Although both groups had body mass index (BMI) within normal range, the study suggests association of relatively higher BMI with “moderate to severe PMS” and “PMDD” group than “no/mild PMS” group (P = 0.0004). This is in agreement with review article from India by Bansal et al. and literature.[19,26]

No statistically significant difference in length of the menstrual cycle (P = 0.3) as well as days of the menstrual bleeding (P = 0.45) was found by us among all the three groups. It is consistent with finding reported by Steiner et al.[3] and Issa et al.[14]

The study findings admit that “PMDD” group and “moderate to severe PMS” group experienced statistically significant more number of days as well as more number of years with premenstrual symptoms than “no/mild PMS” group. This can be explained with finding of association of PMS with onset of symptoms since menarche as well as chronic, relapsing, and remitting nature of illness. Steiner et al.[3] found that “moderate to severe PMS” group and “PMDD” group experienced more number of days of PMS per cycle as compared to “no/mild PMS” group.

The study found an association of menstrual cramps and PMS. This replicates finding of previous several studies.[3,11,14,15,18,21,23] Although menstrual cramps were associated with “moderate to severe PMS” and PMDD group, the frequency of students reporting the psychological symptoms of tiredness, irritability, depression/tension, and decrease interest in work tended to increase with severity of abdominal pain and may be a psychological influence of pain on these affective symptoms.

The study reports significant association of positive family history of PMS in mother/sibling with both “moderate to severe PMS” and “PMDD.” The finding is in agreement with literature.[19,20] Nourjah [15] Nisar et al.[18] and Deuster et al.[29] found that more than half of the study participants (57%) had family history of PMS. It seems that along with other factors, genetic component plays an important role. Twin studies also suggest the presence of a genetic component.[30,31,32]

The study findings indicate that more participants in “moderate to severe PMS” and PMDD group reported the onset of symptoms when they first began to have periods. According to the literature [6] and study by Steiner et al.,[11] 69.3% and 54.5% adolescents reporting severe PMS and PMDD often said that their symptoms began with menarche which is replicated in this study.

This study found no statistically significant association between groups with regards to physical activities such as regular exercise and games. The evidence for an effect of exercise on PMDD symptoms is largely anecdotal. However, regular exercise can be advised as part of a healthy lifestyle regimen.[33] Small trials have suggested aerobic exercise to be beneficial for PMS sufferers, and one trial found high-intensity aerobic exercise to be superior to low-intensity one for PMS treatment.[19] Fewer premenstrual complaints have been found in women participating in sports than in nonathletic women. Exercise training has been associated with decreased breast, fluid, and stress complaints, but not necessarily with improvements in anxiety or depression.[20] The association between exercise and premenstrual symptoms needs to be further investigated by exploring the type and intensity of physical exercise.

The structured clinical interview is a clinician-administered interview which is more reliable than PSST. The interview excluded the possibility of major depressive disorder, panic disorder, dysthymic disorder, or personality disorder among provisionally “PMDD” diagnosed participants. In this study, the structured clinical interview also identified two participants with provisional diagnosis of “PMDD” who were found to have “no/mild PMS” on PSST.

PSST is highly sensitive tool (sensitivity 90.9%). We can reasonably conclude that PSST is a very useful screening instrument in this population. Predictive value of the negative PSST is also high (97.01%), so the likelihood of in fact not having PMDD when found negative on PSST is very high. Hence, it can be easily excluded those who are not having PMDD.

The predictive value of positive PSST is relatively low, i.e., 28.98%. Hence, it should be followed by more specific tests such as daily record of severity of problems or structured clinical interview for confirmation of diagnosis and planning further interventions.

Findings of this study need to be confirmed by large-scale community cross-sectional survey including young girls for obtaining more precise prevalence rates among this age group. Comparison of PSST with gold standard prospective daily diaries of symptoms for diagnostic agreement can be done. PSST is a useful and easy to administer screening test for probable diagnosis of PMS and PMDD.

The study has certain limitations. It included a highly selective sample which comprising college students. The reporting of premenstrual symptoms was based on retrospective recall of the participants adding a recall bias in data collection. As there was no prospective diary charting of PMS symptoms, the prevalence rates are of “provisional diagnosis” according to DSM-IV TR research criteria.

Differentiation between “mild PMS” and “no PMS” was not possible because both were in the same group.

CONCLUSION

PMS occurs at similar rates in college students of Bhavnagar as in other Asian countries. PMS is associated with menstrual cramps, positive family history, symptom onset since menarche, and relatively higher BMI. The most common symptoms are “fatigue/lack of energy,” “decrease interest in work” followed by “anger/irritability.” PSST is a useful, sensitive screening tool among this population for provisional diagnosis of PMS and PMDD.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

We heartily thank Dr. Saurabh Shah, who guided us for key points about writing this article. We are also thankful to Dr. Gunvant Zinzala, Dr. Meghana Mevada, Dr. Imran Ratnani, Mr. Bhavesh Joshi (PSW), Mr. Rohit Joshi (PSW) and Mr. Mehul Pandya (PSW) who were always happy to help us during data collection. We sincerely thank Dr. Viral Shah, Dr. Manish Barvaliya, and Dr. Ilesh Kotecha for their critical comments in preparing manuscript. We highly appreciate the all long co-operation and genuine support given by Mr. Harishchandra Chaudhri (Principal), Mr. Anil Mandaliya (Professor), and Smt. Mayuna Gohil (Professor) of Government Nursing College Bhavnagar; Mr. Deepak Parmar (Principal), Mr. Pravinchandra Trivedi (Former Principal) Excel School of Nursing; Mr. Priyej Jain (Principal) Shree Sahajanand Institute of Nursing; Mr. D. Dhandhukiya (Former Principal) and Smt. Shreedevi Dave (I/C Principal) of Smt. N.C. Gandhi and Smt. B. V. Gandhi Mahila Arts and Commerce College Bhavnagar.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Women's Mental Health: An Evidence Based Review. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision, Vol. I. Comprehensive Tables. ST/ESA/SER-A/313. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steiner M, Macdougall M, Brown E. The premenstrual symptoms screening tool (PSST) for clinicians. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2003;6:203–9. doi: 10.1007/s00737-003-0018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parry BL, Berga SL, Cyranowski JM. Psychiatry and reproductive medicine. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan & Sadock's Synopsis of Psychiatry: Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry. 10th ed. New Delhi: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007. pp. 30pp. 867–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vigod SN, Frey BN, Soares CN, Steiner M. Approach to premenstrual dysphoria for the mental health practitioner. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:257–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Medicines Agency, Inc. c2011. [Last updated on 2016 Apr 01; Last cited on 2013 Feb 10]. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2011/08/WC500110103.pdf .

- 7.American Psychiatric Association. Text Revision. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Accortt EE, Bismark A, Schneider TR, Allen JJ. Diagnosing premenstrual dysphoric disorder: The reliability of a structured clinical interview. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:265–7. doi: 10.1007/s00737-011-0209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon MG, Williams JB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM IV. New York: Unpublished Manuscript, Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Disease and Related problems, 10th revision (ICD-10) Geneva: WHO; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steiner M, Peer M, Palova E, Freeman EW, Macdougall M, Soares CN. The premenstrual symptoms screening tool revised for adolescents (PSST-A): Prevalence of severe PMS and premenstrual dysphoric disorder in adolescents. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2011;14:77–81. doi: 10.1007/s00737-010-0202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bakhshani NM, Mousavi MN, Khodabandeh G. Prevalence and severity of premenstrual symptoms among Iranian female university students. J Pak Med Assoc. 2009;59:205–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tabassum S, Afridi B, Aman Z, Tabassum W, Durrani R. Premenstrual syndrome: Frequency and severity in young college girls. J Pak Med Assoc. 2005;55:546–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Issa BA, Yussuf AD, Olatinwo AW, Ighodalo M. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder among medical students of a Nigerian university. Ann Afr Med. 2010;9:118–22. doi: 10.4103/1596-3519.68354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nourjah P. Premenstrual syndrome among teacher training university students in Iran. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2008;58:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Singh P, Kumar S, Kaur H, Swami M, Soni A, Shah R, et al. Cross sectional identification of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder among college students: A preliminary study. Indian J Priv Psychiatry. 2015;9:21–7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rapkin AJ, Mikacich JA. Premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual dysphoric disorder in adolescents. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2008;20:455–63. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e3283094b79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nisar N, Zehra N, Haider G, Munir AA, Sohoo NA. Frequency, intensity and impact of premenstrual syndrome in medical students. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2008;18:481–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lentz GM. Primary and secondary dysmenorrhea, premenstrual syndrome, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder-etiology, diagnosis, management. In: Lentz GM, Lobo RA, Gershenson DM, Katz VL, editors. Comprehensive Gynecology. Part V. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier, Mosby; 2012. pp. 791–802. Ch. 36. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parry BL, Berga SL. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, editors. Kaplan & Sadock's Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 8th ed. Vol. II. Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 2316–23. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chayachinda C, Rattanachaiyanont M, Phattharayuttawat S, Kooptiwoot S. Premenstrual syndrome in Thai nurses. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;29:199–205. doi: 10.1080/01674820801970306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banerjee N, Roy KK, Takkar D. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder – A study from India. Int J Fertil Womens Med. 2000;45:342–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kamat SV, Nimbalkar AS, Nimbalkar SM. Premenstrual syndrome in adolescents of Anand-Cross-Sectional Study from India using premenstrual symptom screening tool for adolescents (PSST-A) Arch Dis Child. 2012;97:A136. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cleckner-Smith CS, Doughty AS, Grossman JA. Premenstrual symptoms. Prevalence and severity in an adolescent sample. J Adolesc Health. 1998;22:403–8. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00239-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pearlstein T, Yonkers KA, Fayyad R, Gillespie JA. Pretreatment pattern of symptom expression in premenstrual dysphoric disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:275–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bansal M, Goyal M, Yadav S, Singh V. Premenstrual syndrome – A monthly menace. Indian J Clin Pract. 2012;22:491–4. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stout AL, Grady TA, Steege JF, Blazer DG, George LK, Melville ML. Premenstrual symptoms in black and white community samples. 1986;143:1436–9. doi: 10.1176/ajp.143.11.1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deuster PA, Adera T, South-Paul J. Biological, social, and behavioral factors associated with premenstrual syndrome. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:122–8. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.2.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steiner M, Born L. Diagnosis and treatment of premenstrual dysphoric disorder: An update. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;15(Suppl 3):S5–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Condon JT. The premenstrual syndrome: A twin study. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:481–6. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.4.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kendler KS, Karkowski LM, Corey LA, Neale MC. Longitudinal population-based twin study of retrospectively reported premenstrual symptoms and lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1234–40. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.9.1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vigod SN, Ross LE, Steiner M. Understanding and treating premenstrual dysphoric disorder: An update for the women's health practitioner. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2009;36:907–24, xii. doi: 10.1016/j.ogc.2009.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]