Abstract

Background:

There is an intimate relationship between drugs and criminal behavior. The drug–violence relationship is further complicated by intoxicating doses and/or withdrawal effects of specific drugs. Understanding this relationship is important for both healthcare workers and policy makers.

Materials and Methods:

The study was conducted in Prayas observation home for boys, a short stay home for juveniles-under-enquiry in New Delhi. The present study aims to correlate substance use and criminal behavior by investigating the sociodemographic characteristics and the current trend of substance use among juveniles in New Delhi. In this study, 487 detained juveniles aged between 8 and 18 years were included. The information was obtained by face-to-face semi-structured interviews and juvenile case records maintained by the juvenile home.

Results:

Out of 487 juveniles-under-enquiry booked under different crimes, 86.44% of the sample had a history of substance use. Consumption of tobacco and cannabis were higher when compared to other drugs. Consumption of psychotropic drugs though relatively lesser was related with more serious crimes. There is an increasing trend in serious crimes such as rape, murder/attempt to murder, and burglary committed by juveniles. Drug-crime correlation has been noted among consumption of cannabis with murder, inhalants with rape and opioids with snatching-related crimes.

Conclusion:

Substance use and criminal behavior are clearly interrelated. Greater the involvement in substance abuse, more severe is the violence and criminality. This paper highlights this complex relationship and suggests possible scope of interventions.

Keywords: Criminality, juveniles-under-enquiry, substance use

INTRODUCTION

There is an intimate relationship between substance use and criminal behavior. At times, the relationship among the two can be murky and confounding. Drugs can have both direct and indirect effects on violence and criminal behavior. The drug–violence relationship is further complicated by intoxicating doses and/or withdrawal effects of specific drugs. According to the UNICEF estimates of 2002, at least 100 million children live in the streets world over with India indicative of the largest number of street children in the world. The WHO estimates that about 90% of these street children misuse some kind of substance. Globally, the problem emerges as a significant public health threat to world's 30–100 million street children.[1] The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees reports that there are 22.3 million uprooted people. An estimated 10 million are children under the age of 18. South Asia is the home to 584 million children of which 330 million are living in poverty with poor access to social, educational, and health sectors.[2] These children are visible everywhere-selling trinkets, picking rags, polishing shoes, working in vehicle repair shops, or serving food in roadside restaurants. The national capital of India, Delhi, with a population of over 16 million has approximately 100,000 street children, and substance use is reported as a major health problem in this segment of population.[3,4] There are no reliable data associating substance use and criminality among the juveniles in Delhi. Understanding this relationship is essential for both healthcare workers and policy makers.

Considering the trends of substance use in India, inhalant use is comparatively recent, comprising a few case reports;[5,6,7] however, substance use by Indian children has been documented for more than a decade now. Benegal et al.[8] assessed 281 children and reported 197 children as users of illicit substances out of which 76% were smoking tobacco, 45.9% were chewing it, 48% were using inhalants, 42% were using alcohol, 15.7% were into cannabis addiction, and 2% opioids. In the National Household survey of drug use, Ray [9] surveyed 40,697 males comprising 8,587 children in the age group of 12–18 years where 3.8% were using alcohol, 0.6% were using cannabis, and 0.2% were using opioids as drugs of choice. A study in 2007 conducted by Saluja et al.[10] reported that opioids were the most common substances (76.2%) and heroin the most common opioid (36.5%). More than half (54.2%) were dependent on nicotine. A study on 163 street boys of Mumbai city in India reported substance use among 132 of the sample studied.[11] In the single largest study on inhalant use in India, Ray et al.[12] studied this phenomenon in 100 inhalant users with purposive sampling and found that although Inhalants were the primary drug of use, most of the users of the substance were also using other substances such as tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, raw opium, heroin, sleeping tablets, cough syrups, and injections in decreasing order of frequency, respectively, where 76% reported tolerance and 56% had experienced withdrawal symptoms in the study.

There are limited studies regarding substance use among juveniles; the linking of substance use and criminality among the juveniles-under-enquiry with the Juvenile Justice System in the national capital has not been clearly estimated.

In this paper, here on the word, juvenile has been used to refer to juveniles-under-enquiry.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study aims to explore the following objectives:

To investigate the sociodemographic correlates of substance use among Juvenile Delinquents in India

To study the current trends of substance use in juveniles-under-enquiry.

To correlate substance use with criminal behavior.

This study was conducted in Prayas observation home for boys, which is a short stay home for juveniles-under-enquiry. The home is run by Prayas, an NGO, under an agreement with the Department of Social Welfare, Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi. It houses 150 children between the ages of 8–18 years at a given point of time with a maximum period of stay of 3 months.

The study is exploratory in nature. To achieve the abovementioned objectives, 487 juveniles aged between 8 and 18 years detained by the Juvenile Justice System were selected with the help of random sampling. The data were collected through case records maintained by the juvenile home and face-to-face semi-structured interviews with sample members conducted by the senior author in 2 weekly visits, over a period of 1 year. One of the key questions posed to the sample in the interview was “which substance do you use primarily, and its duration?”

Case records maintained by juvenile home included an intake form filled by the police officer at the time of the arrest containing information about the crime committed and the social investigation form, a semi-structured questionnaire filled by the probation officer (a counselor or social worker) through face-to-face interview with the juvenile containing information about the their sociodemographic, educational, socioeconomic, drug-use status, etc., correlated with their family contacted physically by the probation officer. Each case record is presented to the Prayas Home manager to ascertain the completeness of the information in each case before its presentation in the Juvenile Justice Court.

Information in these records is further used for each case presentation in Juvenile Justice Court and for individual and family counseling as part of the rehabilitation process.

RESULTS

The results of the study sample of 487 juveniles-under-enquiry aged between 8 and 18 years were analyzed using SPSS software, details of which have been discussed below.

Sociodemographic profiling and Environmental Correlates of Substance use behavior

Age: The present sample included juveniles aged between a minimum of 8 years and a maximum of 18 years with a mean of 14.17 years and a standard deviation of 1.577 indicating that a larger proportion of sample lies in the age group of 15–16 years

Religion: The study sample consists of juveniles from four different religious backgrounds namely Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, and Sikhism with the highest representation of 64.5% of Hindus followed by a sizable 33.5% of Muslim population while Christians and Sikhs only constitute a marginal proportion of 0.2% and 1.8%, respectively

Occupation: The juveniles in the sample studied came from different walks of life comprising child labor constituting the highest proportion of the sample represented with 42.7%. These children usually work in small roadside tea stalls or small factories to earn their daily bread. Although students comprise the next largest representation with a 20.9%, these students go to local government schools where adequate supervision is lacking both in schools and families; the students get into delinquent activities and mix with antisocial agents. Other occupations comprise hawkers (8.6%), rag pickers (6.8%), unemployed and unsupervised children left alone by parents (6.2%), domestic servants (4.9%), beggars (1%), and run-away children from villages (0.8%). In the category “others,” most children were either illiterate/school dropouts and were temporary street vendors with disposable incomes which they earn by selling of trinkets, flowers, etc., in the streets. This category has a representation of 7.6% of the study sample

Income: It has been noted that the majority of the sample belonged to low socioeconomic status and came from poverty stricken areas also known as “slums.” Only a minority (8%) belonged to the “not-so-poor” category whereas the majority belonged to the “very poor” category amounting to 56.3% and “poor” accounting for approximately 35.7% of the sample

Family background: Out of the total 487 juveniles, only 38.4% hailed from a broken family background while the remaining 61.6% had both parents living with them. Furthermore, nuclear family/single-parent-families were the general norms of the family composition of the study sample with 89.1% of the sample falling under this category as compared to barely 10% from joint family background. Statistical analysis highlights that family structure and substance use among juveniles was found to be negatively correlated (P = 0.00). However, broken family structure and criminal behavior among juveniles were found to be positively correlated (P = 0.007). Intact family structure and criminal behaviors among juveniles were found to be negatively correlated (P = 0.007)

Family history of crime and substance use: There is a high prevalence of crime by parents and/or other elder family member in the study sample with nearly half the population (42%) with a history of crime in the family. There is a significant relationship between juvenile criminal behavior and family history of crime (P = 0.005). Positive correlation was observed between criminal history in family and drug seeking behavior in juveniles (P = 0.001). Statistically speaking, there is a significant relationship observed between juvenile criminal behavior and family use of substances (P = 0.00). Significant relationship also exists between juvenile substance use and family history of substance use (P = 0.049)

Current trends of substance use among juveniles-under-enquiry in India.

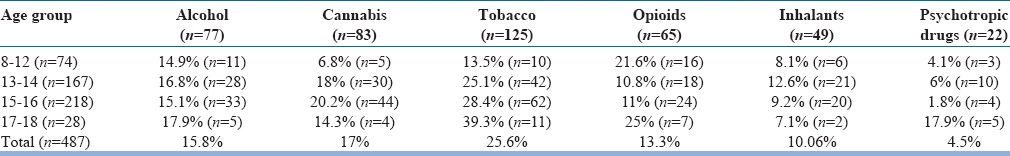

With reference to the above Table 1, it can be inferred that out of 487 juveniles, 86% (n = 421) had a history of substance use. Consumption of tobacco and cannabis were relatively higher with 25.6% and 17%, respectively, when compared to the consumption pattern of alcohol (15.8%), opioids (13.3%), and inhalants (10.06%). Consumption of psychotropic drugs was found to be fairly low in the present sample with meager 4.5%. With regards to the age of drug initiation, initiation of opioids (21.6%) is seen to start at earlier ages of 8–12 years while heavy use of inhalants (12.6%) has been reported to have an onset at the start of teenage at ages between 13 and 14 years. On the other hand, early teenage years (between 15 and 16) mark the inquisitive use of cannabis (20.2%), it is only during late teens (17 and 18 years) that the members of the present sample reported the use of alcohol and psychotropic drugs as intoxicants with 17.9% each. Relatively lesser use of alcohol among sample members could be possibly attributed to the controlled supply of alcohol by government-regulated shops to those below 25 years of age.

Table 1.

Current trends of substance use among Juveniles

Relationship between substance use and criminality

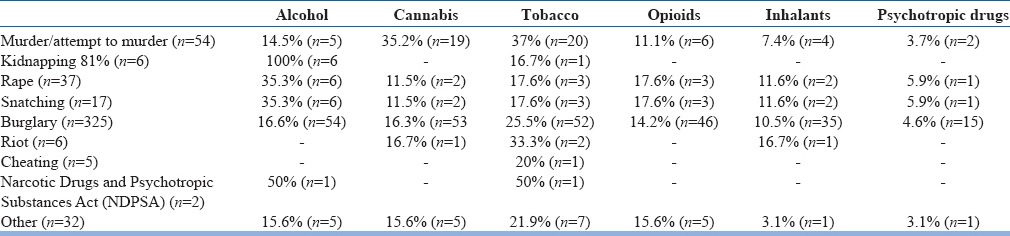

The study sample of 487 juveniles is divided into separate categories of crimes as noted from their case records. It is to be noted that the categories of crimes mentioned in Table 2 are as per the juvenile case records of the juveniles who were booked for different crimes and are in accordance with the terminology used by the Juvenile Criminal Justice System in India. The category “others” includes petty thefts such as pick-pocketing and stealing.

Table 2.

Relationship between substance use and criminality in juveniles

As for other types of criminal behavior, there is an increasing trend noted in the incidence of burglary with an alarming figure of 66.73%, murder/attempt to murder with 11.9%, rape with 11.09%, and snatching-related crimes with 3.5%. Use of solvents/inhalants such as typewriter thinners/whiteners were reported to be higher (16.2%) among the juveniles convicted for rape (n = 37) when compared to other crimes. Similarly, cannabis intake was found to be high (35.2%) among juveniles convicted for murder-related crimes. Likewise, consumption of opioids/heroin was higher in mugging and snatching related crimes. However, intake of psychotropic drugs was common only with crimes of more serious nature such as murder, rape, snatching, and burglary viz-a-viz other drug-crime correlations.

DISCUSSION

The present study examines current trends of substance use in juveniles-under-enquiry and establishes the relationship of substance use and criminal behavior. It also explores the predictor variables that would contribute toward an explanatory model of sociodemographic correlates with criminality and identifies contextual factors related to substance use and criminality among the sample studied.

Sociodemographic variables as predictors of substance use and criminal behavior

Behavior is learned and is influenced by the surroundings one lives in. It has been observed in the present study that most juveniles-under-enquiry came from low socioeconomic backgrounds and poverty-stricken areas commonly referred to as “slums” where economic stability takes precedence over emotional stability, and they are often victims of abuses and neglect. The study also establishes a causal relationship between neglect in childhood and subsequent substance use and criminal behavior which can be supported by existing literature. Researches indicate that children who have been physically abused or neglected are more likely than others to commit violent crimes later in life.[13,14,15] Moreover, community factors, including poverty, low neighborhood attachment, and community disorganization, the availability of drugs and firearms, exposure to violence and racial prejudice, laws, and norms favorable to violence, and frequent media portrayals of violence may contribute to crime and violence.[16] Being raised in poverty has been found to contribute to a greater likelihood of involvement in crime and violence.[17]

History of crime and substance use in family is another predictive variable that has an influence on antisocial behavior among the juveniles-under-enquiry. Family condition leading to crime is seen to be an important factor in this study. Family history of crime and history of substance use in the family were found to have a positive correlation with substance use and criminal behavior among the sample studied. Therefore, parents with a criminal history are seen to be a contributing factor in the juvenile's initiation to crime, and the patterns of crime are transmitted from one generation to another. Baker and Mednick [18] found that youth aged between 18 and 23 with a history of criminality in the family were 3.8 times more likely to have committed violent criminal acts than those without a family history of criminal behavior. Most juveniles, in the present study, reported to have grown up with emotionally broken families and had witnessed parental fighting and domestic violence as they grew up. Results also highlight that the presence of abusive father, physical abuse, presence of a stepparent, and substance use in the family are seen to be common family factors which may act as predictive variables in the antisocial behavior among the sample studied. Paschall [19] states that exposure to violence in the home and elsewhere increases a child's risk for involvement in violent behavior later in life.

Although majority of the juveniles-under-enquiry fall in the preadolescent category (10–15 years) as compared to adolescent category (15–18 years), they were either educated up to primary level or had no formal education. Despite stringent antichild labor laws in India, child labor is still in vogue and consisted of the highest proportion of the sample studied.

Current trends in juvenile substance use in India

Substance use is an emerging health concern among the juveniles in India. The trends of substance use among juveniles are widely varied when compared to western data. NIH statistics [20] reported decline in the rate of tobacco use among teens and an increase in marijuana use; however, the present study reflected the highest consumption of tobacco followed by cannabis among the juveniles-under-enquiry in the sample studied. This may be attributed to the easy availability of cheaper tobacco goods in India, such as Beedis. Those who use cannabis also use tobacco as a substance of choice. Contrary to the report of NIH indicating decline in the use of inhalants, there is an increasing evidence of inhalants use among the Indian children.[3] As also depicted by other studies, easy availability, cheap price and faster onset of action make inhalants a common substance of misuse among urban youth.[21] Although earlier initiation of alcohol (prior to age 13 years) is reported to be common among teenagers (Centre for Disease Control and Prevention 2000),[22] Indian scenario as echoed by the present study reflect a late initiation of alcohol use (late teens). This could be attributed to the stringent policies for the sale of alcohol to the youth in New Delhi. Furthermore, consumption of psychotropic drugs was noted to be relatively lesser compared to the NIH data 2012 of USA. While higher rate of early onset of opioid use might be attributed to association with older peers who abuse the substance.

Substance use, criminality, and juvenile justice

Many juveniles involved with the juvenile justice system experience multiple personal, educational, and family problems. Substance use and involvement in criminal behavior are clearly interrelated. These are the major dependent variables and clearly overlap. Greater the involvement in substance use, more severe is the involvement in delinquency, and vice versa.

The study suggests a rise in serious crimes such as rape, murder, and burglary among juveniles. There were 54 juveniles who committed murder and 37 juveniles who were convicted of rape in the present sample. Lack of schooling or dropout from school makes the younger more likely to engage in delinquent/antisocial behavior. It can be inferred from this study that substance use has direct effects on violence and criminal behavior. Individuals with substance use often commit crimes or engage in violence to obtain drugs, e.g. robbery, theft, prostitution, possession, and selling of narcotics. This can be explained better with the widely used tripartite conception by Goldstein,[23] which establishes relationships between substance use and violence that can be distinguished between (a) psychopharmacological effects, which concern the physiological impact of the substance on behavior, (b) economic effects, which pertain to violence committed to obtain money to purchase intoxicating substances, and (c) systemic effects, which arise as a by-product of the sale and distribution of drugs.

It can be summarized that poverty, broken family, and history of criminality in family can influence and act as predictor variables for substance use and criminality among juveniles. Substance use has been shown to play a contributory role in criminal behavior as noted in the extremely high rates of substance use in criminal justice population. The drug–violence relationship is seen to be further complicated by the intoxicating doses and neurotoxic and/or withdrawal effects of specific substance of use such as alcohol, heroin, or inhalants.

CONCLUSION

This show that substance use and criminal behaviour are clearly interrelated. Greater the involvement in substance abuse more severe is the violence and criminality.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Child Abuse and Neglect. WHO Face Sheet No. 151. 2002. [Last accessed on 2014 Jan 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/inf-fs/en/fact151.html .

- 2.Pant S, Gunashekhar R. Reaching out to substance using kids: Realities and programme priorities for South Asia. In: Tripathi BM, Ambekar A, editors. Drug Abuse News-n-Views (March) New Delhi: National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre, All India Institute of Medical Sciences; 2009. pp. 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma S, Lal R. Volatile substance misuse among street children in India: A preliminary report. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(Suppl 1):46–9. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.580206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma S, Sharma G. Changing Trends of Inhalant Abuse in Juveniles in India. Poster Presentation; NIDA International Forum and CPDD Congress; Scottsdale, Arizona. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahal AS, Nair MC. Dependence on petrol: A clinical study. Indian J Psychiatry. 1978;20:15–9. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Das PS, Sharan P, Saxena S. Kerosene abuse by inhalation and ingestion. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:710. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.5.710a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pahwa M, Baweja A, Gupta V, Jiloha RC. Petrol-inhalation dependence: A case report. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:92–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benegal V, Bhushan K, Seshadri S, Karott M. Drug Abuse Among Street Children in Bangalore: A Project in Collaboration Between the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences and the Bangalore forum for Street and Working Children. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ray R. The Extent, Pattern and Trends of Drug Abuse in India – National Survey. New Delhi: Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment and United Nations Office for Drugs and Crime (UNODC); 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saluja BS, Grover S, Irpati AS, Mattoo SK, Basu D. Drug dependence in adolescents 1978-2003: A clinical-based observation from North India. Indian J Pediatr. 2007;74:455–8. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0077-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaidhana AM, Zahiruddin QS, Waghmare L, Shanbagh S, Zopdey S, Joharapukar SJ. Substance abuse among street children in Mumbai. Vulnerable Child Youth Stud. 2008;3:42–51. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray R, Dhawan A, Yadav D, Chopra A. Inhalant Use Among Street Children in Delhi; a Situational Assessment. A Study Conducted by the National Drug Dependence Treatment Centre. All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Developed Under Govt. of India and World Health Organization Collaborative Program (Biennium 2008-2009) 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989;244:160–6. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zingraff MT, Leiter J, Myers KA, Johnson M. Child maltreatment and youthful problem behavior. Criminology. 1993;31:173–202. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith C, Thornberry TP. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and adolescent involvement in delinquency. Criminology. 1995;33:451–81. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brewer DD, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Neckerman HJ. Preventing serious, violent, and chronic juvenile offending: A review of evaluations of selected strategies in childhood, adolescence, and the community. In: Howell JC, Krisberg B, Hawkins JD, Wilson JJ, editors. Sourcebook on Serious, Violent, and Chronic Juvenile Offenders. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1995. pp. 61–141. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sampson R, Lauritsen J. Violent victimization and offending: Individual, situational, and community-level risk factors. In: Reiss AJ, Roth JA, editors. Understanding and Preventing Violence. Social Influences. Vol. 3. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1994. pp. 1–114. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baker RL, Mednick BR. Influences on Human Development: A Longitudinal Perspective. Boston, MA: Kluwer Nijhoff; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paschall MJ. Exposure to Violence and the Onset of Violent Behavior and Substance Use Among Black Male Youth: An Assessment of Independent Effects and Psychosocial Mediators. Paper Presented at the Society for Prevention Research, June 1996, San Juan, PR.1996. [Google Scholar]

- 20.NIH: National Institute of Drug Abuse. Drug Facts: High School and Youth Trends. 2012. [Last accessed on 2014 Feb 15]. Available from: http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/high-school-youth-trends .

- 21.Kumar S, Grover S, Kulhara P, Mattoo SK, Basu D, Biswas P, et al. Inhalant abuse: A clinic-based study. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50:117–20. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.42399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Youth risk behavior surveillance – United States, 1999. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:1–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein PJ. The drugs-violence nexus: A tripartite conceptual framework. J Drug Issues. 1985;15:493–506. [Google Scholar]