Abstract

Context:

Although electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is considered a very effective tool for the treatment of psychiatric diseases, memory disturbances are among the most important adverse effects.

Aims:

This study aimed to assess prospectively early subjective memory complaints in depressive and manic patients due to bilateral, brief-pulse ECT, at different stages of the treatment, compare the associations between psychiatric diagnosis, sociodemographic characteristics, and ECT characteristics.

Settings and Design:

This prospective study was done with patients undergoing ECT between November 2008 and April 2009 at a tertiary care psychiatry hospital of 2000 beds.

Materials and Methods:

A total of 140 patients, scheduled for ECT with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (depressive or manic episode) or unipolar depression according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders IV diagnostic criteria, were included in the study and invited to complete the Squire Subjective Memory Questionnaire (SSMQ) before ECT, after the first and third sessions and end of ECT treatment.

Statistical Analysis:

Mean values were compared with the Kruskal–Wallis test and comparison of the longitudinal data was performed with a nonparametric longitudinal data analysis method, F1_LD_F1 design.

Results:

SSMQ scores of the patients before ECT were zero. SSMQ scores showed a decrease after the first and third ECT sessions and before discharge, showing a memory disturbance after ECT and were significantly less severe in patients with mania in comparison to those with depression.

Conclusions:

These findings suggest an increasing degree of subjective memory complaints with bilateral brief-pulse ECT parallel to the increasing number of ECT sessions.

Keywords: Bilateral electroconvulsive therapy, depression, mania, subjective memory complaint

INTRODUCTION

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an important option for the treatment of depression.[1] The efficacy of ECT in mania has also been widely documented for a long time.[2,3,4,5,6] Although ECT is considered a very effective tool for the treatment of psychiatric diseases, memory disturbances are among the most important adverse effects.[7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]

We opted for a validated tool that could be implemented easily to assess early subjective memory complaints due to bilateral brief-pulse ECT at different stages of the treatment series. Squire Subjective Memory Questionnaire (SSMQ) is a structured questionnaire developed by Squire, intended to question patients' own views about the extent of memory loss.[7,10,15,16,17,18]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

All consecutive patients hospitalized between November 2008 and April 2009 at a tertiary care psychiatry hospital of 2000 beds, and scheduled for ECT were evaluated for inclusion in this study. Patients aged between 18 and 64 years, diagnosed as having treatment-resistant major depressive disorder (either bipolar or unipolar) or treatment-resistant bipolar manic episode according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) diagnostic criteria, who would receive ECT for the 1st time or those who had not received ECT within the last 6 months were evaluated. The diagnosis and ECT indications were decided by the attending psychiatrists. Response to treatment was evaluated by the attending psychiatrist. Patients with a serious physical or neurological disorder, those with a history of head trauma and with mental retardation and those who could not self-administer SSMQ were excluded from the study. Patients who were able to complete initial cognitive assessments were enrolled in the study. A total of 140 patients (79 males and 61 females) were included in the study. The patients were informed about the procedure and the study, and their written informed consents were obtained. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice.

Assessment

The sociodemographic data of patients were obtained and recorded in the form developed for this purpose (ECT form). The psychiatric diagnoses were ascertained with the help of the Turkish version of Structured Clinical Interview Form for DSM-IV (SCID-I).[19,20] Before the first ECT session, the global cognitive functioning of the patients was assessed by the Turkish version of mini-mental state examination (MMSE).[21,22] Patients with MMSE >25 were included in this study. SCID and MMSE were administered by a senior psychiatry resident (S:B.).

The SSMQ, developed for subjective assessment of memory, was also administered 1 day before the first ECT session and repeated 2 h after the 1st, 3rd ECT sessions, and end of ECT treatment. We evaluated the participants after examining their consciousness and orientation. The psychiatrist enrolling the subjects ensured whether the subjects could be oriented to the test.

SSMQ is self-administered and contains 18 items. The patients' answers are scored between -4 (worse than before), 0 (same as before), and +4 (better than before) points, the sum of which are added together to obtain a final score. A negative score shows an increase in the degree of forgetfulness. SSMQ was translated to Turkish by an English-speaking psychiatrist.

Electroconvulsive therapy administration technique

All patients were administered bilateral brief-pulse frontotemporal ECT (with a Thymatron IV device Somatics Inc., Lake Bluff, IL, USA) at the ECT Center, 3 times a week, every other day in the mornings. The patients were fasted for 6 h before the procedure. General anesthesia was induced by intravenous administration of appropriate anesthetic agents, with succinylcholine for muscle paralysis. Half-age method was used in determining the initial intensity of stimulus seizures shorter than 25 s were considered inadequate, and the dose was increased 50%, with a maximum of 3 times in a session.[23,24] In the subsequent sessions, when the duration of convulsions decreased to 25–30 s, the dose was increased 10%.

Concomitant medications

All patients were taking combinations of psychotropic medications (antidepressants, antidepressants + antipsychotics, and antipsychotics) at maximally tolerated doses, without clinical improvement, and ECT treatment was considered necessary by their attending psychiatrists. Their usual psychopharmacological therapy continued during the course of the study. The pharmacotherapy of the patients was not restricted in any way in accordance with the protocol of this study, and a comparison on the possible effects of the drugs was not included in the design of the study.

Statistical analysis

The duration of seizure, mini-mental test scores, and SSMQ scores was examined with Shapiro–Wilk test. As the continuous variables did not show a normal distribution, they were presented as median (interquartile range) and minimal-maximal values, whereas categorical variables such as gender, marital status, and educational level were presented as numbers (percent). The duration of seizures and differences in total ECT sessions in diagnostic groups were examined with Kruskal–Wallis analysis, the differences in SSMQ scale scores between the measurement time points were examined with F1_LD_F1 design.[25,26,27] The results of F1_LD_F1 design were presented as ANOVA-type test statistical results. In factors where significant differences were detected, relative treatment effects (RTE) for dual comparisons were evaluated. As additional information, mean ± standard deviation (mean ± SD) values were given in patient groups and measurement time points. IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 (IBM Corp., Released 2012. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and MS-Excel 2013 software were used in statistical analysis, calculations, and graphic drawings. “nparLD” module was used in F1_LD_F1 design in R program.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic characteristics

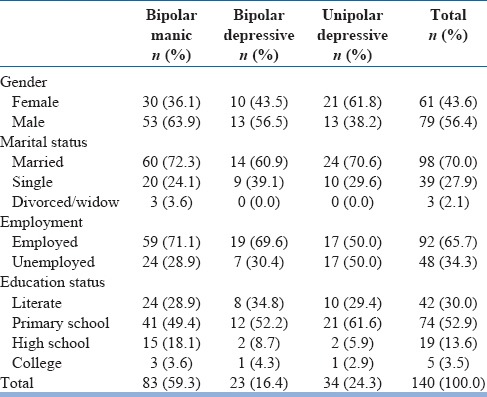

A total of 140 patients were included in this study (79 [56.4%] males and 61 [43.6%] females). The mean age of male patients was 45.47 ± 8.54 years, and mean age of females was 42.1 ± 4.4 years. About 83 of the 140 patients (59.3%) had a diagnosis of bipolar mania, 23 (16.4%) had bipolar depression, and 34 (24.3%) had unipolar depression.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

The sociodemographic characteristics of the patients according to psychiatric diagnosis

Electroconvulsive therapy characteristics

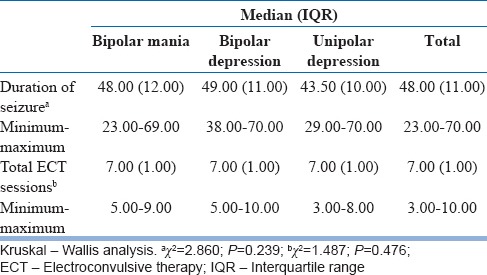

The diagnostic groups were found to be homogenous according to the number of ECT sessions administered (χ2 = 1.487, P = 0.476).

The mean duration of seizure of patients with bipolar mania, bipolar depression, and unipolar depression were similar in different diagnostic groups (χ2 = 2.860, P = 0.239). ECT Characteristics according to diagnosis are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Electroconvulsive therapy characteristics according to diagnosis

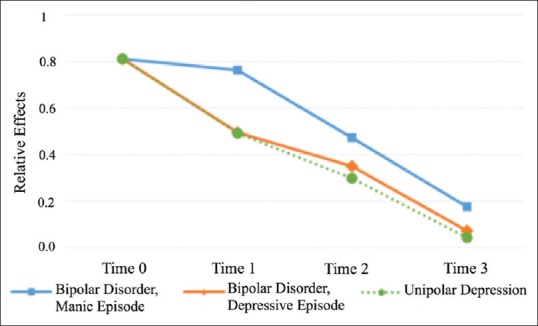

Subjective evaluation of memory

SSMQ scores of the patients before ECT were zero. SSMQ scores showed a significant decrease after the first, third, and at the end of ECT sessions. This decrease was parallel to the increasing number of ECT sessions. The scores were observed to decrease in time in all diagnostic groups and presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The changes of relative effects of Squire Subjective Memory Questionnaire scores of groups according to time of measurement

The group with bipolar mania had reported significantly milder subjective memory complaints in comparison to those with bipolar depression and unipolar depression.

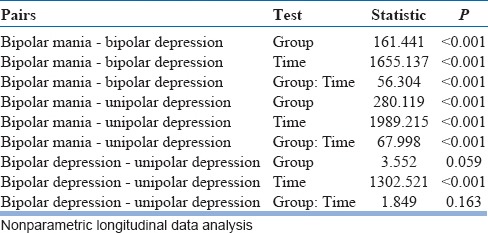

The scale scores of patients with bipolar mania were significantly different than those of patients with bipolar depression and unipolar depression (P < 0.001 for all tests). The changes in scores of patients with bipolar mania in time were different than the other patients (P < 0.001 for group: Time test). The changes in time of SSMQ scores of patients with bipolar/unipolar depression were found to be similar (P = 0.163).

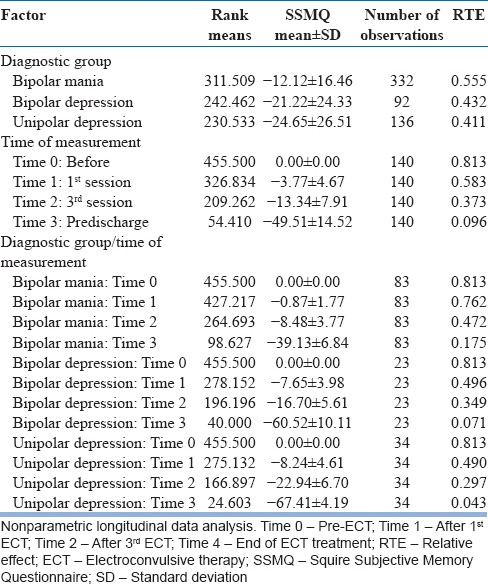

Results of all pair-wise comparisons are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Pair-wise comparisons

When the groups were evaluated generally, the scores of patients in the bipolar mania group were higher than the other two groups (RTE = 0.555, P < 0.001), when the measurement times were evaluated, pretreatment scores were higher than other times (RTE = 0.813). Rank means ± SDs and relative impact of each score are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Relative effects obtained according to diagnostic groups and measurement times

When the differences in SSMQ scores were examined according to diagnostic groups and time, a significant difference independent from time was found between the groups and a significant difference independent from group was found between the times (P < 0.001). Furthermore, a difference was detected between diagnostic groups in terms of change of scores according to time (F = 35.699, P < 0.001).

A decrease was detected in SSMQ scores of all patients, starting after the first session, showing a significant difference in comparison with the pretreatment evaluation, and also a significant increase in progressive sessions.

In comparison of diagnostic groups, the decrease in scores in patients with depression (bipolar or unipolar) was similar, whereas this decrease was significantly less in manic patients.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we are reporting progressive subjective memory complaints in depressive and manic patients during a bilateral brief-pulse ECT course, and it is more in depression than mania.

While early studies had reported a negative impact of ECT on subjectively rated memory, more recent studies showed a weak effect or a positive effect, implying that bilateral brief-pulse ECT may not produce the complaints that were seen with bilateral sine-wave ECT and others have reported even weaker less negative effects of unilateral placement.[8,9,15,28,29,30,31] Brakemeier in a recent study reported with brief-pulse unilateral versus bilateral ECT with improved SSMQ scores few days after ECT relative to baseline. Chee Ng also reported improvement in SSMQ scores at 6th ECT, the end of sessions, and 1 month with RUL ECT. Mayur comparing baseline with 24 h after 8th session and 3 months have found a significant improvement in terms of SSMQ scores at every time point and also have drawn attention to advantages of ultra-brief-pulse.[11,16,32] In this study, contrary to a number of studies, improvement in SSMQ scores, with brief-pulse, could not be demonstrated. It is highly possible that the administration of SSMQ within 2 h of ECT was a major factor.

Another influence may also be the preference of bitemporal ECT in this study, our results were only in line with of Squire et al.[17] at post-ECT 1-week scores, where all patients were administered bilateral ECT and patients reporting increased memory complaints which return to pre-ECT levels at 6th months. Our results reflect the early phase findings and as the patients were not followed up to examine long-term side effects of bilateral, brief-pulse ECT on subjective memory we cannot deduce any conclusion for long-term effects on the patients.

In this study, bipolar manic patients had reported significantly less subjective memory complaints than depressive patients (either bipolar or unipolar). Most western studies using the SSMQ are done on patients with treatment-resistant depression. Although different results were reported by some studies, a significant association was found between the severity of depression and subjective memory disturbances.[33] Studies evaluating subjective memory reported a significant relationship between the severity of depressive symptoms and SSMQ scores and marked improvement after the termination of an ECT course.[15,16] There is few study reporting memory complaints of bipolar manic patients.[12,13,34,35] The presence of less severe subjective memory complaints in manic patients in comparison to those in depression in this study may be considered to be an influence of the affective state at the time of the evaluations. The absence of examining if the mood status of the patients were associated with subjective memory complaints by scales may have prevented our evaluation of this effect and differences.

Limitations

As this study reflects existing treatment protocols, its findings provide information from our actual psychiatric practice and should be interpreted with caution, taking into consideration several influences that might be present. One of these influences may be continuation of the use of psychoactive medications. ECT administration in the presence of pharmacotherapy may prevent definite conclusions. Another limitation may be the lack of a control group of similar patients treated with pharmacotherapy only. Furthermore, preference of bitemporal ECT in this study (due to institutional protocols), restrict any conclusions regarding optimal electrode placement. Finally, patients were not followed up to examine long-term side effects of bilateral, brief-pulse ECT on retrograde subjective memory in this study due to financial restrictions. Future studies using more sensitive neuropsychological methods with longer-term follow-up are will be welcome.

As healthcare professionals working at a psychiatric facility treating a large number of psychiatric patients, some with ECT, we believe that ECT is very important and beneficial. We also believe that our results reflect the early phase findings. A longer-term follow-up study should be done, for which we could not provide the necessary funds, as a result of which we had to evaluate only the early phase cross-sectional findings, which we shared. We believed that a better understanding on memory disturbances associated with ECT will be beneficial for both clinicians, and the society in general. Further longer-term studies in the future will provide clearer answers to various questions that are not addressed in this study.

CONCLUSION

These findings suggest an increasing degree of subjective memory complaints with bilateral brief-pulse ECT parallel to the increasing number of ECT sessions. Although we found electroconvulsive therapy to cause some memory disturbances in the acute phase, we still believe that its benefits largely overweight these. Long-term follow-up studies may provide more data on this issue.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank, Mesut Akyol, PhD, Department of Biostatistics Yıldırım Beyazıt University Medical School, and Dilek Tunali, MD, for reviewing the text and references with a critical eye.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kho KH, van Vreeswijk MF, Simpson S, Zwinderman AH. A meta-analysis of electroconvulsive therapy efficacy in depression. J ECT. 2003;19:139–47. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200309000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medda P, Toni C, Perugi G. The mood-stabilizing effects of electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2014;30:275–82. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0000000000000160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Versiani M, Cheniaux E, Landeira-Fernandez J. Efficacy and safety of electroconvulsive therapy in the treatment of bipolar disorder: A systematic review. J ECT. 2011;27:153–64. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181e6332e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mukherjee S, Debsikdar V. Unmodified electroconvulsive therapy of acute mania: A retrospective naturalistic study. Convuls Ther. 1992;8:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mukherjee S, Sackeim HA, Lee C. Unilateral ECT in the treatment of manic episodes. Convuls Ther. 1988;4:74–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bharadwaj V, Grover S, Chakrabarti S, Avasthi A, Kate N. Clinical profile and outcome of bipolar disorder patients receiving electroconvulsive therapy: A study from North India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2012;54:41–7. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.94644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser LM, O'Carroll RE, Ebmeier KP. The effect of electroconvulsive therapy on autobiographical memory: A systematic review. J ECT. 2008;24:10–7. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181616c26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schat A, van den Broek WW, Mulder PG, Birkenhäger TK, van Tuijl R, Murre JM. Changes in everyday and semantic memory function after electroconvulsive therapy for unipolar depression. J ECT. 2007;23:153–7. doi: 10.1097/yct.0b013e318065aa0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vamos M. The cognitive side effects of modern ECT: Patient experience or objective measurement? J ECT. 2008;24:18–24. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e31815d9611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Porter RJ, Douglas K, Knight RG. Monitoring of cognitive effects during a course of electroconvulsive therapy: Recommendations for clinical practice. J ECT. 2008;24:25–34. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e31815d9627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mayur P, Byth K, Harris A. Autobiographical and subjective memory with right unilateral high-dose 0.3-millisecond ultrabrief-pulse and 1-millisecond brief-pulse electroconvulsive therapy: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J ECT. 2013;29:277–82. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3182941baf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rami-Gonzalez L, Bernardo M, Boget T, Salamero M, Gil-Verona JA, Junque C. Subtypes of memory dysfunction associated with ECT: Characteristics and neurobiological bases. J ECT. 2001;17:129–35. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Semkovska M, McLoughlin DM. Measuring retrograde autobiographical amnesia following electroconvulsive therapy: Historical perspective and current issues. J ECT. 2013;29:127–33. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e318279c2c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ingram A, Saling MM, Schweitzer I. Cognitive side effects of brief pulse electroconvulsive therapy: A review. J ECT. 2008;24:3–9. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e31815ef24a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prudic J, Peyser S, Sackeim HA. Subjective memory complaints: A review of patient self-assessment of memory after electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2000;16:121–32. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200006000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brakemeier EL, Berman R, Prudic J, Zwillenberg K, Sackeim HA. Self-evaluation of the cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2011;27:59–66. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181d77656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Squire LR, Wetzel CD, Slater PC. Memory complaint after electroconvulsive therapy: Assessment with a new self-rating instrument. Biol Psychiatry. 1979;14:791–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Squire LR, Zouzounis JA. Self-ratings of memory dysfunction: Different findings in depression and amnesia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1988;10:727–38. doi: 10.1080/01688638808402810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Çorapçıoğlu A, Aydemir Ö, Yıldız M, Esen A, Köroğlu E. Turkish version of Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Clinical Version (SCID-I/CV) Ankara: Physicians Publication Association; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JB. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV clinical version (SCID-I/CV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Güngen C, Ertan T, Eker E, Yaşar R, Engin F. Reliability and validity of the standardized mini mental state examination in the diagnosis of mild dementia in Turkish population. Turk J Psychiatry. 2002;13:273–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”.A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petrides G, Fink M. The “half-age” stimulation strategy for ECT dosing. Convuls Ther. 1996;12:138–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Canbek O, Menges OO, Atagun MI, Kutlar MT, Kurt E. Report on 3 years' experience in electroconvulsive therapy in bakirkoy research and training hospital for psychiatric and neurological diseases: 2008-2010. J ECT. 2013;29:51–7. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e318282d126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunner E, Munzel U, Puri ML. Rank score tests in factorial designs with repeated measures. J Multivar Anal. 1999;70:286–317. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunner E, Domhof S, Langer F. Nonparametric Analysis of Longitudinal Data in Factorial Experiments. New York: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Noguchi K, Gel YR, Brunner E, Konietschke F. nparLD: An R software package for the nonparametric analysis of longitudinal data in factorial experiments. J Stat Softw. 2012;50:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kellner CH, Tobias KG, Wiegand J. Electrode placement in electroconvulsive therapy (ECT): A review of the literature. J ECT. 2010;26:175–80. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181e48154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Fuller R, Keilp J, Lavori PW, Olfson M. The cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy in community settings. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:244–54. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daniel WF, Crovitz HF, Weiner RD, Rogers HJ. The effects of ECT modifications on autobiographical and verbal memory. Biol Psychiatry. 1982;17:919–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lisanby SH, Maddox JH, Prudic J, Devanand DP, Sackeim HA. The effects of electroconvulsive therapy on memory of autobiographical and public events. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:581–90. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.6.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng C, Schweitzer I, Alexopoulos P, Celi E, Wong L, Tuckwell V, et al. Efficacy and cognitive effects of right unilateral electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2000;16:370–9. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200012000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Devanand DP, Fitzsimons L, Prudic J, Sackeim HA. Subjective side effects during electroconvulsive therapy. Convuls Ther. 1995;11:232–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barekatain M, Jahangard L, Haghighi M, Ranjkesh F. Bifrontal versus bitemporal electroconvulsive therapy in severe manic patients. J ECT. 2008;24:199–202. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e3181624b5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Virit O, Ayar D, Savas HA, Yumru M, Selek S. Patients' and their relatives' attitudes toward electroconvulsive therapy in bipolar disorder. J ECT. 2007;23:255–9. doi: 10.1097/yct.0b013e318156b77f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]