Abstract

“Unmodified”-electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) being considered unethical remained away from the scientific literature, but continued in practice in many parts of the world. The Mental Health Care Bill, 2011, proposed for its banning in India. The aim of this study is to retrospectively observe “how bad was unmodified-ECT” to the patients in a naturalistic setting. The study was done at the Central Institute of Psychiatry, India. Files of patients receiving unmodified ECT during 1990–1995 were retrospectively reviewed. Outcome was evaluated in terms of desired effectiveness and the side effects as noted in the files by the treating team. Six hundred and thirty-seven patients (6.94% of total admission) received ECT with meticulous standard-of-care except provision of anesthesia. Satisfactory improvement was noted in 95.45% patients with no noticeable/reported complication in 89.05%. Premature termination of ECT for complications occurred in 2.19% patients. “Unmodified”-ECT, though unethical, still could ensure favorable outcome with proper case selection and meticulous standard-of-care.

Keywords: Bad, electroconvulsive therapy, meticulous care, unmodified

INTRODUCTION

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) used to be applied without anesthesia and muscle relaxants initially after introduction. Use of anesthetics and muscle relaxants became widespread by late 1950s. With that, ECT gradually entered from “unmodified” to “modified” form. After that, “unmodified”-ECT used to be considered unjustified and unethical. As per policies, “unmodified”-ECT completely fell apart from experimental studies after 1960s.[1] However, in reality, its usage continued even in 21st century in different parts of the world including India (52%) and also in some of the developed countries such as Russia (80%) and Japan (55% of total ECT use).[2] Recently in India, the Mental Health Care Bill, 2011,[3] proposed for banning of unmodified ECT. The Indian psychiatric society came out with its position statement in 2012[4] mentioning that “prohibition of unmodified-ECT seems to be based on issues more related to popular perception rather than scientific evidence.” However, no change was made in the bill and it is waiting to become an act since 2013.

Despite widespread use, there is a lack of recent study on “unmodified”-ECT other than few surveys on the pattern of ECT practice based on respondent's version.[5,6] The aim of this study would be to collect some data and insight rather than valuing judgment regarding “how bad was unmodified ECT” to the patients in a naturalistic setting.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study was done in the Central Institute of Psychiatry (CIP), Ranchi, India. The study design was a retrospective observational study. The data were collected as a corollary to another study “ECT as an etiology of epilepsy – a retrospective study.”[7] Files of all the patients aged 18 years and above receiving ECT from April 1, 1990 to March 31, 1995, were selected for the study. At that time, in CIP, all the patients were given unmodified-ECT. Every single note was carefully scrutinized to find out the antecedents and clinical outcome of ECT. Outcome was evaluated in terms of desired effectiveness and common side effects as noted by the treating team.

RESULTS

A total of 637 patients (6.94% of total admission) with mean age of 27.16 ± 7.90 years received ECT. Predominantly, mood disorder patients (70.80%) with unmanageable injurious behaviors (42.70%), poor responder to drugs (26.84%), catatonia (16.33%), and suicidality (14.13%) were given ECT. There was mandatory pre-ECT clinical evaluation including dental, musculoskeletal, cardio-respiratory and neurological check-up, fundoscopy and electrocardiogram. Nonharmful beneficial effects of ECT used to be discussed in group meeting of patients to allay apprehension. All the patients were given ECT with unmodified, bitemporal, sine wave device. There was separate ECT station in each ward with a spacious room having one ECT table, ECT machine, Boyle's apparatus, and an attached recovery space. During administration, there used to be two doctors – junior and senior resident, multiple nursing, and ward staffs, but no anesthetist. Boyle's apparatus was used for mandatory pre-ECT oxygenation and sub-shock after care. Careful manual restraining of patients during convulsion was done at all vulnerable joints by multiple ward staffs and trainee nurses. Close clinical monitoring was done by a doctor and staff nurses till complete postictal recovery and subsequent feeding. Mean duration of convulsion in a session of ECT was 38.75 ± 10.33 s. There was down-titration of current parameters whenever the seizure duration used to go beyond 60 s. ECT was given in thrice weekly sessions till adequate improvement or plateau of response and then tapered over next few sessions. Mean number of sessions in a course of ECT was 7.60 ± 3.86. During ECT, all the patients were on psychotropics, but antiepileptics and benzodiazepines used to be omitted.

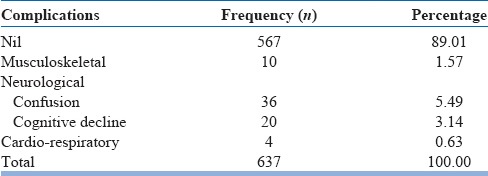

Sub-shocks were quite common (62.64% patients) showing a significant positive correlation with the age, total number of sessions, and presence of depressive disorder; but not with the post-ECT confusion. Following any sub-shock, there used to be proper cardio-respiratory care with adequate moist oxygen inhalation, spacing for few minutes with close clinical monitoring, and cancellation of session in case of multiple sub-shock. One patient had cardio-respiratory arrest and two had apnea following sub-shock managed with cardio-pulmonary resuscitation (CPR) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Peri-electroconvulsive therapy complications during electroconvulsive therapy

Regarding peri-ECT complications, only the subjective complaints of the patients and obvious clinical signs were documented in files. Musculoskeletal complications, the most commonly blamed complications for unmodified ECT, were surprisingly low. But out of ten, five were severe enough to omit subsequent ECT. Rest suffered from muscle pain requiring analgesic and no X-ray was advised for them. Surprisingly, there was also no note of subjective complaints of post-ECT headache.

Among neurological complications, post-ECT confusion was noted in 36 patients lasting for few minutes to about an hour with or without agitation. Out of 36, 25 required injectable diazepam 10 mg and in rest, they were self-limiting. Confusion showed a correlation (P < 0.05) with mean voltage and mean duration of convulsion, but not concurrent psychotropics such as lithium.

Cognitive problems in terms of subjective complaints of forgetfulness and objectively verified disturbed orientation, immediate and recent memory was found in 20 (3.14%) patients, out of them 18 were depressed. In all the patients, ECT continued with increased spacing and reduction of concurrent dosage of psychotropics, particularly tricyclic-antidepressants. Cognitive problems were transient over 2–3 weeks and showed a positive correlation with depression, antidepressants, age of the patients (P < 0.01), and number of sessions (P < 0.05), but not with the number of courses and occurrence of confusion.

Apart from these complications, there was no report of tardive seizure, status epilepticus, post-ECT dyskinesia, or prolonged obtundation after ECT even in combination with therapeutic doses of phenothiazines, tricyclic-antidepressants, and lithium.

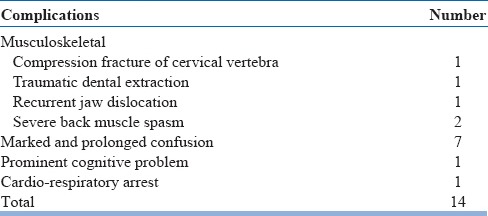

There were four cases of cardio-respiratory complications during ECT, three after sub-shock requiring CPR. In one known hypertensive patient, there was accelerated hypertension after the tenth session requiring increment in ongoing dosage of nifedipine for 2 days. None of them had any neurological sequel and ECT continued after 2 days' interval [Table 2].

Table 2.

Premature termination of electroconvulsive therapy due to serious complications

Surgical emphysema developed in a 26-year-old female patient where post-ECT X-ray revealed compression fracture of the fourth cervical vertebra. The patient was managed conservatively with cervical collar, analgesic, and haloperidol. Traumatic dental extraction occurred on the first ECT session in a 45-year-old female of acute psychosis. There was recurrent jaw dislocation in a 28-year-old female patient of recurrent mania, who had past history of safe treatment with ECT. Severe back muscle spasm without any fracture in X-ray was the reason for discontinuation of ECT in two more young male patients.

Five out of 7 patients in whom ECT discontinued for confusion improved within 1–2 days requiring only additional injectable diazepam, but no investigation. In two patients, confusion was further prolonged leading to shifting to nearby medical college. One patient was diagnosed as neurosyphilis and the other remained undiagnosed. Unfortunately, both died within a month.

ECT, discontinued for cognitive problem after three sessions in a 35-year-old male depressed patient, restarted after 3 weeks changing antidepressant imipramine to fluoxetine. The patient showed satisfactory improvement on eight sessions.

There was safe and effective use of ECT in few patients with serious medical morbidity. Seven hypertensive elderly depressed patients, two having additional ischemic heart disease with left ventricular hypertrophy, one having diabetes, and one having asthma were successfully treated with ECT. ECT was successfully given to two patients with past history of meningitis, one with childhood epilepsy, and five with comorbid mental retardation without any complication at that time and following next 3 years of follow-up.

Regarding overall outcome, clinically satisfactory improvement was noted in 95.14% patients. No rating scales were used. Poor improvement was particularly mentioned in the files of only 17 (2.67%) patients, out of which, 12 were of long duration schizophrenics, four were manic, and one was acute psychosis.

DISCUSSION

In case of “unmodified”-ECT, with no obligation of arranging anesthesia, rampant use remains an apprehension. But in this institute, the extent of use (6.94%) was much lower than Afro-Asian and Latin-American countries (25%),[2] due to strict selection criteria of patients. Proper adherence to guideline [1] has ensured a favorable outcome even out of a primitive sine wave device in this place (95.14%) which is comparable to other advanced places such as the United Kingdom, California, and Hong Kong.[2,8,9] Regarding complications, there must be under-reporting for not having any screening tool and only the noticeable side effects got recorded in the files. However, even the serious complications were much less than those reported prior to 1960s.[1] In that age, “host susceptibility” due to improper case selection, very high number of ECT sessions in quick succession, and inadequate standard of care during ECT were probably the reasons behind those complications rather than unsophisticated instrument.[10]

CONCLUSION

This article does not justify “unmodified”-ECT, but it shows strict adherence to proper standard of care that ensures favorable outcome even in “unmodified”-ECT with unsophisticated instrument.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank Dr. S. Haque Nizamie, Retired Professor of Excellence and Ex Director, Central Institute of Psychiatry, Ranchi, India… as the then head of the institute and thesis guide.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Electroconvulsive Therapy: Task Force Report No. 14. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leiknes KA, Jarosh-von Schweder L, Høie B. Contemporary use and practice of electroconvulsive therapy worldwide. Brain Behav. 2012;2:283–344. doi: 10.1002/brb3.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. The Mental Health Care Bill. 2011. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 30]. Available from: http://www.mohfw.nic.in .

- 4.Indian Psychiatric Society. Position Statement on the Draft Mental Health Care Bill. 2011. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 30]. Available from: http://www.Ips-online.org .

- 5.Agarwal AK, Andrade C, Reddy MV. The practice of ect in India: Issues relating to the administration of ect. Indian J Psychiatry. 1992;34:285–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chanpattana W, Kunigiri G, Kramer BA, Gangadhar BN. Survey of the practice of electroconvulsive therapy in teaching hospitals in India. J ECT. 2005;21:100–4. doi: 10.1097/01.yct.0000166634.73555.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ray AK. Does electroconvulsive therapy cause epilepsy? J ECT. 2013;29:201–5. doi: 10.1097/YCT.0b013e31827e5672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kramer BA. Use of ECT in California, revisited: 1984-1994. J ECT. 1999;15:245–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung KF. Electroconvulsive therapy in Hong Kong: Rates of use, indications, and outcome. J ECT. 2003;19:98–102. doi: 10.1097/00124509-200306000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devinsky O, Duchowny MS. Seizures after convulsive therapy: A retrospective case survey. Neurology. 1983;33:921–5. doi: 10.1212/wnl.33.7.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]