Abstract

Plasticity in inhibitory receptors, neurotransmission, and networks is an important mechanism for nociceptive signal amplification in the spinal dorsal horn. We studied potential changes in GABAergic pharmacology and its underlying mechanisms in hyperalgesic priming, a model of the transition from acute to chronic pain. We find that while GABAA agonists and positive allosteric modulators reduce mechanical hypersensitivity to an acute insult, they fail to do so during the maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming. In contrast, GABAA antagonism promotes antinociception and a reduction in facial grimacing after the transition to a chronic pain state. During the maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming, we observed increased neuroligin (nlgn) 2 expression in the spinal dorsal horn. This protein increase was associated with an increase in nlgn2A splice variant mRNA, which promotes inhibitory synaptogenesis. Disruption of nlgn2 function with the peptide inhibitor, neurolide 2, produced mechanical hypersensitivity in naive mice but reversed hyperalgesic priming in mice previously exposed to brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Neurolide 2 treatment also reverses the change in polarity in GABAergic pharmacology observed in the maintenance of hyperalgesic priming. We propose that increased nlgn2 expression is associated with hyperalgesic priming where it promotes dysregulation of inhibitory networks. Our observations reveal new mechanisms involved in the spinal maintenance of a pain plasticity and further suggest that disinhibitory mechanisms are central features of neuroplasticity in the spinal dorsal horn.

Keywords: Hyperalgesic priming, GABA, Neuroligin 2, Dorsal horn, BDNF

1. Introduction

Changes in the spinal dorsal horn γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) system are implicated in pathological pain. Alterations in dorsal horn GABAergic function include a loss of the neurotransmitter itself,17,19 a loss of GABAergic neurons,52 a reduction in the pharmacological efficacy of certain GABAA receptors (GABAAR),3,4 a disruption of the neuronal Cl− gradient that diminishes inhibitory hyperpolarization,13,14,16,18,30 and a potential switch in the polarity of behavior effect of agonists and antagonists.1 An underlying feature of these changes may be differences in postsynaptic plasticity between inhibitory and excitatory neurons in response to afferent input,27 decreased expression or function of the neuron-specific K+, Cl− cotransporter 2 (KCC2),14,23,38,39 and/or altered expression of the inhibitory synapse adhesion molecule neuroligin 2 (nlgn2).15 KCC2 establishes low intracellular Cl− concentrations that are required for inhibitory hyperpolarization on opening of GABAARs. Loss of KCC2 expression after injury is associated with the development of mechanical allodynia and the generation of neuropathic pain.14,18,23,30 Nlgn2 recruits GABAARs and its postsynaptic scaffolding protein, gephyrin, to synapses thereby regulating inhibitory synapse formation and strength,11,36 which directly contributes to the inhibitory and excitatory balance of neuronal networks.9 Hence, expression changes in GABAAR regulatory proteins such as KCC2 and nlgn2 can have a profound impact on GABAergic circuit function and may be a driver of pathological conditions in the CNS (central nervous system) including chronic pain.6,23

While the above evidence suggests a role for loss of normal inhibition in the dorsal horn following injury,41 the possible role of changes in spinal GABAergic circuitry as a driver of the transition from acute to chronic pain is unknown. Using a mouse model of hyperalgesic priming, which models the transition from an acute to chronic pain state,5,24,28,40,42,43 we sought to assess alterations in GABAergic circuit function during the initiation and maintenance phases of hyperalgesic priming using behavioral measures with GABAAR agonists and antagonists. Simultaneously, we monitored expression changes of nlgn2 and KCC2 in the spinal dorsal horn during the course of hyperalgesic priming with the underlying hypothesis that persistent changes in one or both of these proteins may reflect their predominant role in establishing neuroplasticity underlying pathological pain.

We found an inversion of the effects of GABAAR agonists and antagonists in the maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming. These changes were observed with a concomitant persistent increase in nlgn2 protein expression in the spinal dorsal horn with no evidence for altered KCC2 expression in this model. Importantly, pharmacological targeting of nlgn2 with a newly discovered peptide reversed hyperalgesic priming. These observations point to a disruption in normal spinal inhibition and to nlgn2 as a novel target in the transition to a pathological pain state.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Experimental animals

All procedures that involved use of animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Arizona and The University of Texas at Dallas and were in accordance with International Association for the Study of Pain guidelines. All behavioral studies were conducted using male ICR mice weighing between 20 and 25 g Harlan Laboratories (Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A). Mice were used in behavioral experiments starting 1 week after arrival at the animal facility at University of Arizona School of Medicine or University of Texas at Dallas. Animals were housed with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and had food and water available ad libitum.

2.2. Behavioral testing

Mechanical withdrawal threshold testing was conducted using the up-down method.8 Animals were placed in acrylic boxes with wire mesh floors and habituated for a minimum of 1 hour before the measurement of mechanical withdrawal thresholds of the appropriate hind paw using calibrated von Frey filaments (Stoelting, Wood Dale, IL). To establish hyperalgesic priming, we administered 0.1 ng of recombinant human interleukin 6 (IL-6; R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) in 25 µL sterile 0.9% NaCl into the left hind paw with an intraplantar (i.pl.) injection and measured their mechanical withdrawal thresholds at various time points after injection. Alternatively, intrathecal (i.t.) injection of 100 ng of recombinant human brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF; R&D systems) dissolved in 5 µL sterile 0.9% NaCl was used to induce hyperalgesic priming. On day 7, animals were baselined for mechanical thresholds and subsequently injected in the left hind paw with 100 ng of PGE2 (prostaglandin E2) (Cayman Chemical; Ann Arbor, MI) in 10 µL sterile 0.9% NaCl. Afterward, mechanical withdrawal thresholds were measured at 3 and 24 hours. For all i.t. injections, drugs were administered in 5 or 10 µL sterile 0.9% saline or water to animals anesthetized with isoflurane for no longer than 3 minutes. For all intraperitoneal injections, drugs were dissolved in sterile saline and administered in 200 µL volume.

Mouse Grimace Scale was used to quantify spontaneous pain in mice.29 We scored the changes in the facial expressions (using the facial action coding system) 24 hours after i.pl. PGE2 injection.

The experimenters measuring mechanical withdrawal thresholds or scoring mouse facial expressions were always blinded to the experimental conditions. Mice were randomized to groups by a blinded experimenter and mice of individual groups were never housed together (eg, home cages were always mixed between experimental groups). Compounds used are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Experimental compounds used in this study.

| Experimental compounds | Vendor | Cat. no. | Dose and reference | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscimol | Tocris | 0289 | 0.3 µg i.t.3,4 | GABAA agonist |

| Midazolam | Tocris | 2831 | 10 µg i.t.3,4 | Benzodiazepine |

| THIP (garboxadol) | Tocris | 0817 | 3 µg i.t.3,4 | GABAA agonist |

| SR95531 (gabazine) | Tocris | 1262 | 150 ng i.t.1 | GABAA antagonist |

| SKF82958 | Sigma-Aldrich | C130 | 4.1 µg i.t.27 | Dopamine D1/D5 agonist |

| Neurolide 2 (HSEGLFQRA tetramer) | Synthesized for this work | N/A | 0.8 µg i.t. dose modified from van der Kooij et al48 | nlgn2 inhibitory peptide |

| Acetazolamide | Sigma-Aldrich | A6011 | 22.5 µg i.t. dose2–4 |

GABAA, γ-aminobutyric acid type A; i.t., intrathecal; i.pl., intraplantar; nlgn2, neuroligin 2.

Adaptations are themselves works protected by copyright. So in order to publish this adaptation, authorization must be obtained both from the owner of the copyright in the original work and from the owner of copyright in the translation or adaptation.

2.3. Immunoblotting

Harvested tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer containing 10 mM HEPES at pH 7.9, 20 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.05% Triton X-100, protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail 2/3 (P5726, P0044; Sigma Aldrich). Then the lysate was spun at 1000g for 15 minutes at 4°C, and the supernatant was collected and measured for protein concentration using BCA (bicinchoninic acid assay) Protein Assay Kit (PI-23, 223; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Approximately 20 µg of protein per sample was mixed with loading buffer, 4× Laemmli sample buffer (161-077; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), with 5% dithiothreitol (DTT) v/v (161-0611; Bio-Rad) and heated to 95°C for 5 minutes to facilitate denaturation of protein and then ran on 7.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for separation. The exception to this are the samples shown in Figure 3E, which were not heat treated and prepared without the reducing agent DTT to preserve KCC2 oligomers.26 When the run was completed, the gels were transferred onto PVDF (polyvinylidene difluroide) membranes (IPVH00010; Millipore, Billerica, MA) overnight at 4°C. The membranes in the following day was collected and blocked with 5% dry milk for 1 hour at room temperature and then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. In the following day, these membranes were incubated in the horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) for chemiluminescent detection onto a radiography film or on ChemiDoc Touch (170-8370; Bio-Rad) after the substrate (WBKLS0500; Millipore) application to the membranes. Densitometric analyses were performed on immunoblots with ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD) using the gel analysis tool available as a plugin from McMaster University (www.macbiophotonics.ca). Densitometry was done following instructions given for this plugin for ImageJ. Antibodies used are given in Table 2.

Figure 3.

Intrathecal (i.t.) brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) treatment dynamically modulates expression of neuroligins and neurexin in the spinal dorsal horn. (A) The i.t. injection of BDNF causes mechanical hypersensitivity that resolves within 4 days. Following the resolution of mechanical hypersensitivity, on day 7, intraplantar (i.pl.) injection of PGE2 precipitates mechanical hypersensitivity only in animals previously exposed to BDNF and this mechanical hypersensitivity completely resolves within 7 days of PGE2 injection (N = 4 for BDNF group). (B) Spinal dorsal horn collected from animals at 24 hours after BDNF i.t. injection (black box in (A)) showed a significant reduction of neuroligin (nlgn)1 and nrxn1β expression and no change in nlgn2 and KCC2 expression level. (C) In the dorsal horn of animals that received i.t. BDNF 7 days previously (red box in (A)), increased expression of nlgn2 was observed, while the expressions of nlgn1, nrxn1β, and KCC2 were comparable with vehicle-treated mice. (D) DRGs from mice 7 days after BDNF (red box in (A)) showed no expression changes of any of these target proteins. (E) Western blots are shown run under nondenaturing conditions (described in Materials and methods) with a long (top) and short (bottom) exposure from dorsal horn samples of mice treated 7 days previously with vehicle (V) or BDNF (B). No change in KCC2 monomers or multimers was observed. (F) BDNF-primed mice were treated with PGE2 and then 3 hours later received i.t. injections of acetazolamide (22.5 ng) or vehicle and mechanical hypersensitivity was measured at the indicated time points. No difference was observed between groups (N = 5 per group). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; 2-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc test. N = 6 to 8 mice per group except (A) and (F).

Table 2.

Antibodies used for immunoblotting.

| Antibody | Vendor | Cat. no. | Dilution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neuroligin 1 | NeuroMab | 75-160 | 1:2000 |

| Neuroligin 2 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-14089 | 1:1000 |

| Neurexin 1β | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | sc-14334 | 1:2000 |

| GAPDH | Cell Signaling | 2118 | 1:6000 |

| KCC2 | NeuroMab | 75-013 | 1 µg/mL |

KCC2, K+; Cl−, cotransporter 2.

2.4. Nlgn2 inhibitory peptide synthesis

Inhibitory nlgn2 peptide (neurolide 2) was synthesized as a tetramer composed of 4 monomer peptides HSEGLFQRA coupled to a lysine backbone. The inhibitor was prepared by semi-manual solid-phase fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl/tert-butyl synthetic strategy performed in fritted syringes using a Domino manual synthesizer obtained from Torviq (Niles, MI).22,47 The compound was fully deprotected and cleaved from the resin by treatment with 91% trifluoroacetic acid, 3% H2O, 3% 1,2-ethanedithiol, and 3% thioanisole. After ether extraction of scavengers, the compound was purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (Waters model 600 with a C18 reversed-phase column; 15–20 mm, 22 × 250 mm; 218TP022; Grace Vydac, Hesperia, CA). The peptide was eluted with a linear gradient of CH3CN (0.1%), CF3CO2H (20%–60%) at a flow rate of 5.0 mL/min. Purified compound was lyophilized and reconstituted in dimethyl sulfoxide and kept at −80°C before the experiment. The structure was characterized by electrospray ionization on a Bruker 9.4 T Fourier transform ion-cyclotron resonance (high-resolution accurate mass) mass spectrometer.

2.5. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted from the tissues using the RNAqueous Total RNA kit (AM1912; Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA), following manufacturer’s protocol for tissue samples. Extracted RNA was further treated by DNAse digestion using TURBO DNA-free kit (AM1907; Life Technologies) to remove any genomic contamination. RNA quantification and purity were tested using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer. Total RNA of 20 ng was used for cDNA synthesis with iScript Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-qPCR kit (170-8890; Bio-Rad). Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) reactions were performed on an ABI 7500 Real-time PCR System with SYBR Green PCR master mix (4309155; Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) using default 2-step (95–60°) amplification. Reactions were run in triplicates, and melt curves were performed at the end of every run to ensure amplification of single species. All the CT value of each target was normalized to GAPDH (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase) value, and then the vehicle and treatment groups were compared using ΔΔCT method.32

All primer pairs were tested and validated for their efficiency in the sample type by running a RNA standard curve, generated by 5-fold dilutions of 6 points. Only the primers with efficiency that fell between 90% and 110% with a single, shoulder-free peak upon melt curve analysis were used. Primers sequences are listed in Table 3. Moreover, no reverse transcriptase (no-RT) and no template (NT) controls were run for every sample set or primer pairs to check for genomic DNA contamination or primer dimer, respectively.

Table 3.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction primers.

| Target | Sequence | Amplicon size |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroligin 1 | ||

| F | GGA ACG CCA CTC AGT TTG CT | 119 |

| R | TTG GAC GTA TGA TGA AAC CAC AT | |

| Neuroligin 2-pan | ||

| F | AGG CAG GGA GGA GGA CTT G | 74 |

| R | CAC CTT AAC ACT GCT CCA CGA A | |

| Neuroligin 2A | ||

| F | GCT CAA TCC GCC AGA CAC | 67 |

| R | GCC GTG TAG AAA CAG CAT GA | |

| Neuroligin 2(−) | ||

| F | CAC CTA CGT GCA GAA CCA GA | 79 |

| R | AGA GTC CCG GAT ATC GTC CT | |

| GAPDH | ||

| F | AGG TCG GTG TGA ACG GAT TTG | 123 |

| R | TGT AGA CCA TGT AGT TGA GGT CA |

2.6. Data analysis and statistics

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Data were analyzed with GraphPad (San Diego, CA) Prism Version 6 for PC or Mac. Statistical differences between groups were measured by 2-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc test unless otherwise noted. The a priori level of significance was set at 95%.

3. Results

3.1. Hyperalgesic priming changes spinal GABAAR pharmacology

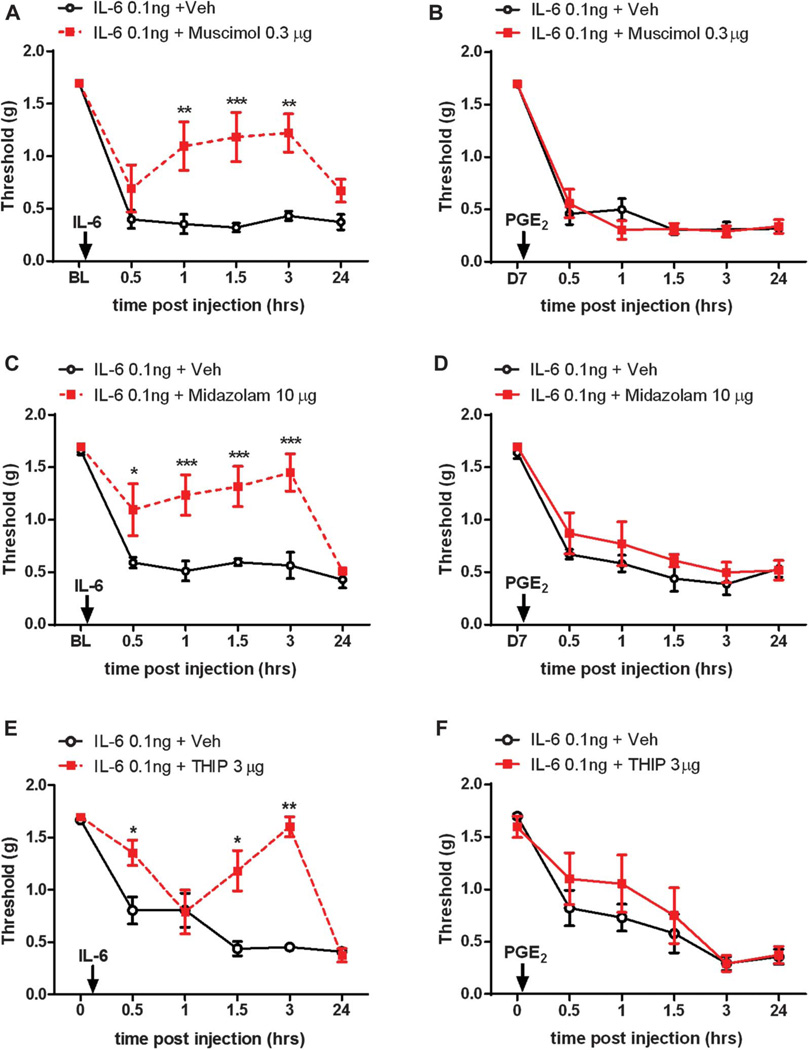

Several lines of evidence indicate that changes in GABAAR pharmacology occur in the spinal dorsal horn following inflammation or peripheral nerve injury. We have previously observed that the analgesia produced by spinal application of GABAAR agonists and positive modulators is significantly reduced in neuropathic animals and that this effect is rapidly restored with carbonic anhydrase inhibition.3,4,41 Others have reported an inversion of the valence of GABAAR pharmacology after peripheral inflammation, wherein spinal application of GABAAR agonist now exacerbates mechanical hypersensitivity, whereas a GABAAR antagonist now produces analgesia.1 We investigated the possible changes in GABAAR pharmacology in the setting of hyperalgesic priming. We sought to address this question by comparing analgesic effects of GABAAR agonists, positive allosteric modulators and antagonists during the initiation and maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming. When we injected the GABAAR agonist, muscimol (0.3 µg), i.t. at the time of i.pl. injection of IL-6, we observed that muscimol produced a robust alleviation of mechanical hypersensitivity lasting for at least 3 hours postdrug administration (Fig. 1A). However, when the same dose of muscimol was administered i.t. at the time of PGE2 i.pl. injection in IL-6-primed mice, muscimol failed to influence mechanical hypersensitivity (Fig. 1B). Similarly, spinal application of the benzodiazepine, midazolam (10 µg), and the δ subunit preferring GABAA receptor agonist, THIP (3 µg), attenuated IL-6-induced mechanical hypersensitivity (Figs. 1C and E), but again, the same dose of midazolam and THIP injected i.t. in primed mice failed to block the PGE2 induction of mechanical hypersensitivity (Figs. 1D and F).

Figure 1.

GABAA receptor agonists and positive modulators lose their analgesic efficacy during the maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming. (A) The intrathecal (i.t.) injection of GABAAR agonist, muscimol, at the time of i.pl. injection of interleukin 6 (IL-6) prevented animals from developing mechanical hypersensitivity for up to 3 hours. When the same dose of muscimol was given to mice that received IL-6 7 days before PGE2 intraplantar (i.pl.) injection, it failed to alleviate mechanical hypersensitivity (B). (C) A benzodiazepine, midazolam, given i.t. at the time of IL-6 i.pl. injection attenuated mechanical hypersenstivity for up to 3 hours but when injected to mice that were previously exposed to IL-6, midazolam failed to block PGE2-induced mechanical hypersensitivity (D). (E) The i.t. injection of THIP significantly attenuated IL-6-induced mechanical hypersensitivity but failed to do so when given to IL-6 primed animals at the time of PGE2 i.pl. injection (F). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; 2-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc test. N = 6 to 8 mice per group.

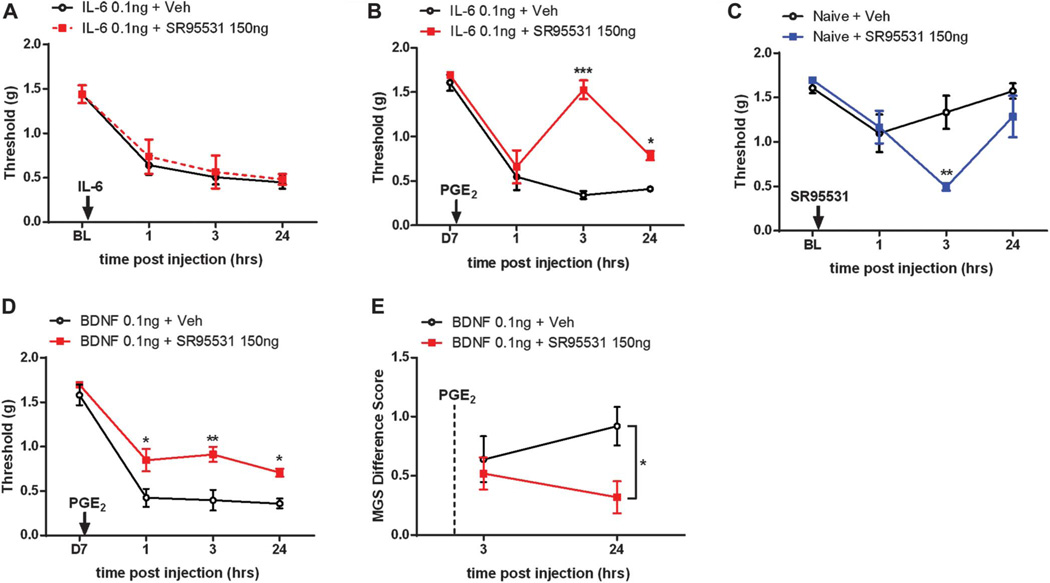

The loss of analgesic effects of muscimol, midazolam, and THIP in primed animals led us to investigate the effects of the GABAAR antagonist, SR95531 (also called gabazine). Similarly to previous findings in rats in an acute inflammatory setting,1 we gave i.t. injections of SR95531 to mice at the same time that we administered i.pl. IL-6 and measured mechanical hypersensitivity. We observed that animals receiving both IL-6 and SR95531 (150 ng) did not show greater mechanical hypersensitivity than animals that only received i.pl. IL-6 (Fig. 2A). However, when the same dose of SR95531 was administered spinally at the time of PGE2 i.pl. injection in primed mice, it significantly attenuated mechanical hypersensitivity (Fig. 2B). We subsequently determined that 150 ng of SR95531 produces a robust mechanical hypersensitivity when injected i.t. in naive animals (Fig. 2C) as shown previously in a broad variety of studies (reviewed in Ref. 37).

Figure 2.

GABAA receptor antagonist causes antinociception selectively in interleukin 6 (IL-6)-primed and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-primed animals. (A) Animals that received intrathecal (i.t.) injection of SR95531, GABAAR antagonist, with IL-6 intraplantar (i.pl.) treatment showed similar level of mechanical hypersensitivity as animals that only received i.pl. IL-6 injection. (B) When the same dose of SR95531 was injected to animals that were previously exposed to IL-6, animals showed a significant attenuation of PGE2-induced mechanical hypersensitivity. (C) Spinal injection of SR95531 produced robust mechanical hypersensitivity in naive mice. SR95531 treatment led to a significant attenuation of PGE2 precipitation of priming (D) and less facial grimacing (E) in animals that were primed with i.t. BDNF 7 days previously. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; 2-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc test. N = 6 to8 mice per group.

Although our previous experiments used a peripherally directed injection of IL-6 to produce priming, we have also shown that an i.t. injection of pronociceptive molecules like BDNF produces hyperalgesic priming in mice.34 Moreover, disruption of BDNF signaling with sequestering treatments or small molecule trkB antagonists reverses hyperalgesic priming induced by IL-6 or by other pronociceptive factors like agonists of protease-activated receptors.34,46 Therefore, BDNF is a key molecule for the initiation and maintenance of hyperalgesic priming.24,40 We then asked if BDNF-evoked hyperalgesic priming was also reduced by GABAAR antagonism. The i.t. injection of SR95531 in BDNF-primed mice also alleviated mechanical hypersensitivity in response to PGE2 injection (Fig. 2D), mirroring the results obtained with IL-6-primed mice (Fig. 2C). We have also previously demonstrated that PGE2 injection in primed animals causes an increase in facial grimacing.28,46 This measure is reflective of changes in the affective state of mice.29 We tested whether this affective state was also influenced by GABAAR antagonism in primed mice. Here, we saw significantly less grimacing at 24 hours post-i.t. SR95531 injection paired with PGE2 into the hind paw (Fig. 2E). Therefore, both IL-6- and BDNF-induced hyperalgesic priming causes changes in spinal GABAAR pharmacology, suggesting a persistent change in the spinal GABAergic system in hyperalgesic priming.

3.2. Spinal injection of BDNF acutely reduces nlgn1 and persistently increases nlgn2 expression in the spinal dorsal horn

Hyperalgesic priming with either IL-6 or BDNF produced clear changes in GABAAR pharmacology in the spinal cord. In order to better understand the cellular mechanisms that may mediate this change, we sought to determine the expression profiles of nlgn1, nlgn2, and KCC2 during both initiation and maintenance phases of hyperalgesic priming. We first gave i.t. injections of BDNF to 2 groups of mice and collected spinal dorsal horns and DRGs (dorsal root ganglion) either 24 hours (when mechanical hypersensitivity is full-blown) or 7 days (when it has resolved) after the injection (Fig. 3A). We chose to use spinal injection of BDNF as our priming stimulus to focus our investigation on the mechanisms of postsynaptic plasticity in the spinal dorsal horn. Tissues were quantified for their expression of nlgn1 and nlgn2, neurexin 1β (nrxn1β), which is a presynaptic binding protein of neuroligins, and KCC2. We observed that nlgn1 and its binding partner, nrxn1β, were significantly downregulated 24 hours after BDNF i.t. injection, whereas there was no significant change to nlgn2 or KCC2 expression at this time point (Fig. 3B). Seven days after BDNF injection, however, nlgn2 was significantly upregulated in spinal dorsal horn tissues, whereas nlgn1 and nrxn1β expression returned to levels found in vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 3C). No changes to KCC2 protein expression were detected at this time point (Fig. 3C). When lumbar DRGs were isolated from these animals and analyzed for nlgn1, nlgn2, and nrxn1β expression (KCC2 was not analyzed because it is not expressed in DRG),14 we observed no changes in protein expression at 7 days following BDNF exposure (Fig. 3D). To look at potential changes in KCC2 expression more carefully, we performed Western blots on spinal dorsal horn tissues 7 days after BDNF treatment under nondenaturing conditions to observe KCC2 monomers and multimeric protein complexes. We also showed 2 different exposures. We did not observe any changes in KCC2 expression under these conditions in the spinal dorsal horn 7 days after BDNF treatment (Fig. 3E). Lee and Prescott recently showed that the carbonic anhydrase inhibitor acetazolamide inhibits mechanical allodynia only when it arises because of chloride dysregulation and has no effect when disinhibition arising because of alterations in GABAA function is responsible for mechanical allodynia.31 We therefore used a dose of acetazolamide that we have shown to be effective in reducing neuropathic mechanical hypersensitivity in rats2 and mice3,4 to see if this would reverse PGE2-induced precipitation of hyperalgesic priming. Consistent with our Western blot data for KCC2, acetazolamide had no effect in this experimental paradigm suggesting that chloride dysregulation is not responsible for mechanical hypersensitivity in this setting (Fig. 3F). These findings suggest that nlgn1 and nlgn2 are dynamically regulated by spinal BDNF and may play a role in hyperalgesic priming, whereas KCC2 is unlikely to contribute to this effect.

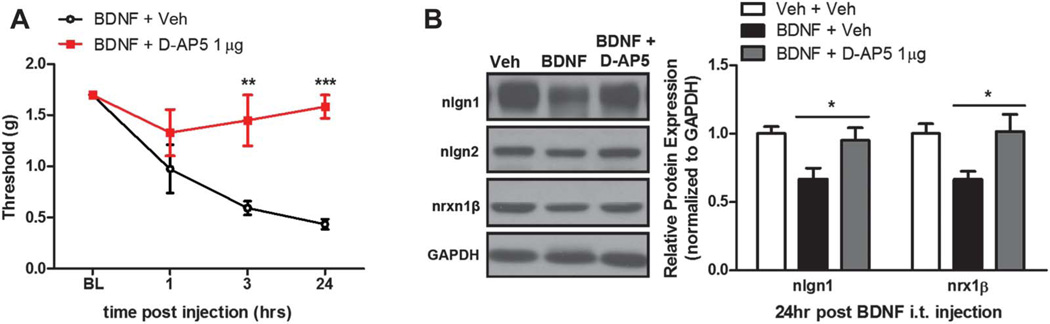

3.3. Acute BDNF-induced mechanical hypersensitivity and nlgn1 and nrxn1β downregulation is n-methyl-d-aspartate receptor dependent

We first assessed mechanisms involved in the acute regulation of nlgn1 expression following BDNF exposure. BDNF-evoked changes in neuronal excitability are linked to n-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) function. For example, BDNF application to the spinal cord potentiates NMDAR-mediated nociceptive synaptic relays25 and increases C-fiber-evoked field potentials,53 both of which are completely blocked by pretreatment with NMDAR antagonists. Behavioral data from many groups demonstrate that spinal antagonism of NMDARs attenuates mechanical hypersensitivity induced by i.t. injection of BDNF, suggesting that BDNF requires NMDAR activation for its pronociceptive effects.35 We sought to determine if NMDAR activation after BDNF i.t. injection is required for the reduction of nlgn1 and nrxn1β expression at the peak of BDNF-induced mechanical hypersensitivity. We administered the NMDAR antagonist, D-AP5 (1 µg, i.t.), 15 minutes before BDNF i.t. injection and tested for changes in mechanical withdrawal threshold at 1, 3, and 24 hours (Fig. 4A). We found that animals that received D-AP5 before BDNF injection were completely free of mechanical hypersensitivity at 24 hours. When the spinal dorsal horns were collected from these animals and analyzed for nlgn1 and nrxn1β expression, BDNF-treated animals, as previously observed, showed downregulation of nlgn1 and nrxn1β (Fig. 4B). This effect was completely blocked by D-AP5 pretreatment (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-induced downregulation of neuroligin (nlgn)1 and nrxn1β is blocked by a NMDA antagonist. (A) Pretreatment with n-methyl-d-aspartate receptor antagonist, D-AP5, 15 minute before BDNF intrathecal injection completely blocked mechanical hypersensitivity. (B) Spinal dorsal horn collected from animals at 24 hours after coinjection of BDNF and D-AP5 revealed that D-AP5 prevented downregulation of nlgn1 and nrxn1β. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; 2-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc test. N = 5 to 6 mice per group.

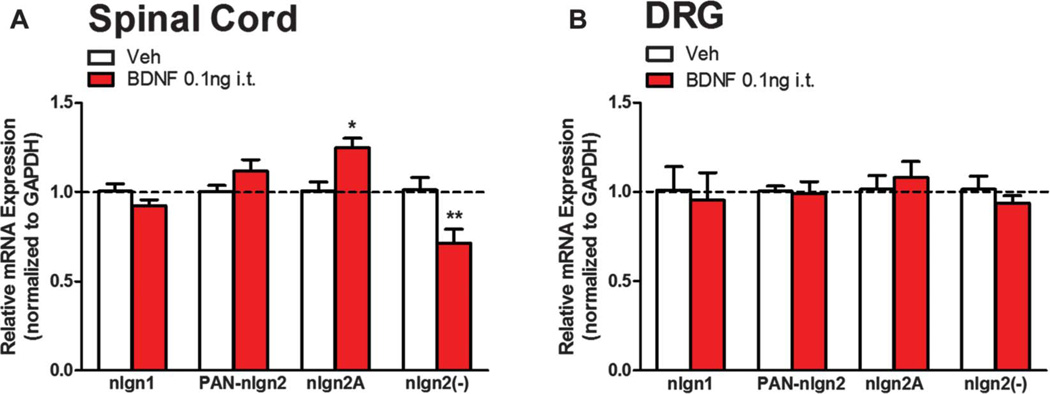

3.4. BDNF persistently modulates expression of splice isoforms of nlgn2 in the spinal cord

We next sought to determine mechanisms regulating changes in nlgn2 expression in the maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming. One possibility is that BDNF exposure causes a persistent increase in nlgn2 mRNA production and/or stability. Neuroligin genes produce multiple splice isoforms.20,44 In the case of nlgn2, it is alternatively spliced in its ectodomain, where a short alternative exon that gives rise to 20 amino acids is either present or absent (nlgn2A or nlgn2(−), respectively). Interestingly, shifting the balance between nlgn2A and nlgn2(−) transcripts has been shown to influence the ratio of glutamatergic to GABAergic synapse formation. When the nlgn2A to nlgn2(−) ratio is increased, more GABAergic synapses form, whereas a decrease in the ratio promotes glutamatergic synapses in hippocampal culture.10 Differential expression of these splice isoforms have also been implicated in neuropathic pain.15 Therefore, we assessed nlgn2 mRNA levels, including these splice variants, using qPCR on spinal dorsal horn and DRG total RNA extracts. We administered i.t. injections of BDNF to mice and collected spinal dorsal horns and DRGs 7 days later for total RNA extraction. When we analyzed nlgn2 mRNA expression profiles from these tissues, we observed that pan-nlgn2 expression was unaltered (Fig. 5A). We observed a splice isoform-specific regulation wherein the nlgn2A splice variant was significantly increased and nlgn2(−) transcripts were decreased in the spinal dorsal horn of BDNF-primed animals (Fig. 5A). We checked for the expression of these splice isoforms in DRGs to find a possible contribution of primary afferent terminals in the increased expression level of nlgn2A (Fig. 5B). Similar to the protein expression data from DRG, nlgn2 isoform expression levels were unchanged in BDNF-primed animals. These findings suggest that BDNF shifts the spinal nlgn2A to nlgn2(−) ratio, which based on previous studies, should stimulate formation of inhibitory synapses.

Figure 5.

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) induces differential expression of neuroligin (nlgn)2 splice isoforms. Vehicle or BDNF were injected intrathecally and 7 days later dorsal horn of the spinal cord and DRGs were collected. (A) By quantitative polymerase chain reaction from dorsal horn, nlgn2A mRNA expression was upregulated, whereas nlgn2(−) mRNA showed reduced expression. (B) No changes were observed in DRGs. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01; 2-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc test. N = 5 to 6 mice per group.

3.5. Pharmacological targeting nlgn2 reverses hyperalgesic priming

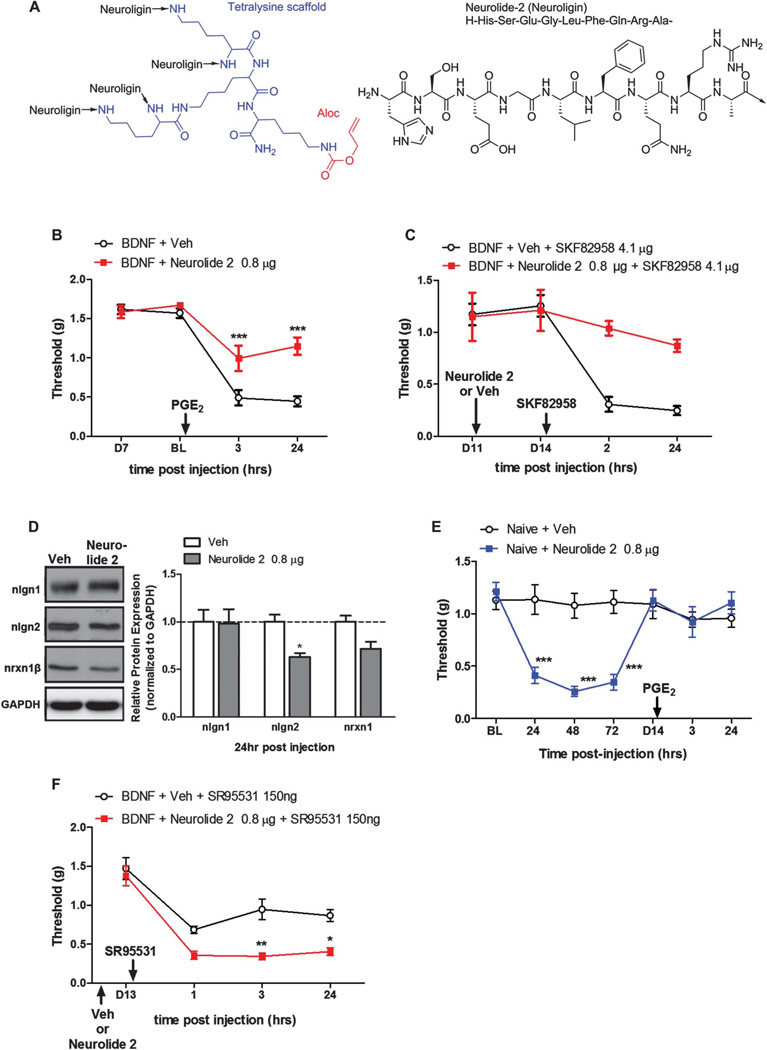

Increased protein levels for nlgn2 coupled with increased mRNA levels of nlgn2A after BDNF priming suggest augmented numbers of inhibitory nlgn2-expressing synapses in the maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming. Our pharmacological experiments with GABAAR agonists and antagonists indicate an inversion of the polarity of this neurotransmitter system in the maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming. Based on these observations, we predict that interference with nlgn2 function should have differential effects in naive vs primed mice. We tested this using a newly discovered peptide (Neurolide 248; Fig. 6A) that selectively interferes with nlgn2 function. We first primed mice with i.t. injection of BDNF. Then, 7 days later, during the maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming, mice received a single injection of neurolide 2 (0.8 µg). We then precipitated mechanical hypersensitivity with i.pl. injection of PGE2 24 hours after the neurolide 2 administration. We saw that animals that received neurolide 2 showed a significant reduction of mechanical hypersensitivity following PGE2 injection (Fig. 6B). Neurolide 2 also reversed the effect of a dopamine D1/D5 agonist given i.t., which we have previously shown promotes mechanical hypersensitivity exclusively in primed mice (Fig. 6C)28.

Figure 6.

Neurolide 2 disruption of neuroligin (nlgn)2 signaling reverses hyperalgesic priming. (A) Structure of neurolide 2. (B) Intrathecal (i.t.) neurolide 2 injection, 24 hours before PGE2 intraplantar (i.pl.) injection, significantly attenuated mechanical hypersensitivity at 3 and 24 hours postinjection. (C) The i.t. neurolide 2 injection 11 days after brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) exposure was followed by i.t. injection of the D1/D5 agonist SKF82958 on day 14. SKF82958 failed to precipitate hyperalgesic priming in mice previously treated with neurolide 2. (D) Spinal dorsal horn collected 24 hours after neurolide 2 injection showed a reduction in nlgn2 protein expression by Western blotting without changes to nlgn1 or nrxn1β expression. (E) Naive mice receiving i.t. neurolide 2 developed mechanical hypersensitivity lasting approximately 4 days but failed to develop hyperalgesic priming to PGE2 injection. (F) BDNF-primed mice treated with i.t. neurolide 2 on day 11 after injection show mechanical hypersensitivity in response to the GABAA antagonist SR95531 given i.t. on day 13 after BDNF treatment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; 2-way analysis of variance with Bonferroni post hoc test. N = 5 to 6 mice per group.

We confirmed the selectivity of neurolide 2 by checking for a reduction of nlgn2 expression in the spinal dorsal horn 24 hours after injection. Neurolide 2 reduced nlgn2 expression but had no effect on nlgn1 or nrxn1β (Fig. 6D). We tested the effect of neurolide 2 on naive mice, where we predict that inhibition of nlgn2 function should induce mechanical hypersensitivity, consistent with observation in rats using shRNA.15 Neurolide 2 i.t. injection caused robust mechanical hypersensitivity in naive mice that resolved within 7 days (Fig. 6E). Interestingly, when we tested these mice for the presence of hyperalgesic priming, they failed to demonstrate a response to PGE2 injection (Fig. 6E) despite showing a previous period of mechanical hypersensitivity roughly equal to the duration and intensity evoked by spinal BDNF. Finally, we sought to determine whether neurolide 2 treatment would reverse changes in GABAergic pharmacology apparent during the maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming. To do this, we primed mice with BDNF, treated with neurolide 2 or vehicle 11 days later and then exposed all mice to the GABAA antagonist SR95531. Although SR95531 did not cause mechanical hypersensitivity in BDNF primed mice treated with vehicle on day 11, neurolide 2–treated mice now showed a robust mechanical hypersensitivity (Fig. 6F). This demonstration is consistent with observations in naive mice and indicates that neurolide 2 treatment reverses pathological changes in GABAergic circuitry that are a key component of maintenance of hyperalgesic priming. Therefore, increased nlgn2-expressing inhibitory synapses in the spinal dorsal horn mediate the pathological neuroplasticity underlying the maintenance of hyperalgesic priming.

4. Discussion

Our findings collectively support the following primary conclusions: (1) hyperalgesic priming causes an inversion in the polarity of spinal GABAAR pharmacology; (2) spinal nlgn1 and nrxn1β expression is transiently reduced during the initiation phase of hyperalgesic priming via an NMDAR-dependent mechanism; (3) nlgn2 protein and a splice isoform of nlgn2 mRNA, nlgn2A, are increased in the dorsal horn during the maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming; and (4) pharmacological targeting of nlgn2 with the recently discovered peptide inhibitor neurolide 2 reduces nlgn2 protein expression and reverses the established hyperalgesic priming. These findings demonstrate that the maintenance of pathological pain plasticity underlying hyperalgesic priming relies on alterations in dorsal horn inhibitory pharmacology and circuitry that are regulated by a novel nlgn2-mediated mechanism.

A variety of previous reports attribute the generation of mechanical hypersensitivity after peripheral nerve injury to anionic plasticity governed by KCC2 and/or changes in GABAergic tone that may depend on loss of neurotransmitter (reviewed in Refs. 23,37,41). A potential manifestation of this change in GABAergic function is altered GABAAR-mediated pharmacology after peripheral injury. In fact, an inversion of the valence of spinal GABAAR pharmacology during CFA (Freund's completed adjuvant)-induced peripheral inflammation, wherein i.t. injection of a GABAAR antagonist produced antinociception, whereas a GABAAR agonist exacerbated mechanical hypersensitivity, was noted by Anseloni and Gold.1 Likewise, in neuropathic pain models, we have previously observed a loss of analgesic efficacy for a variety of GABAAR agonists and allosteric modulators that can be rapidly restored by inhibition of carbonic anhydrase.3,4 This finding, which is supported by modeling studies,16 is most readily explained by deficits in KCC2 function.41 Using a hyperalgesic priming model, we find that spinal GABAAR antagonism produced antinociception at a dose that is normally pronociceptive in nonprimed animals. A possible explanation for this is a BDNF-mediated persistent decrease in KCC2 expression and/or function.13 However, we failed to observe any persistent change in KCC2 protein expression in the spinal dorsal horn in this model and acetazolamide did not reverse mechanical hypersensitivity after hyperalgesic priming. This latter point is important because it has recently been shown that acetazolamide reverses mechanical allodynia and changes in dorsal horn physiology consistent with chloride dysregulation but has no effect if altered GABAA function is responsible for this effect.31 Nevertheless, further investigation is required to positively rule out the contribution of KCC2 to our observations because KCC2 activity can also be regulated through phosphorylation and/or protein trafficking,23 mechanisms that we did not explore, and an important caveat to our conclusions. A very recent study suggested a novel mechanism of dorsal horn plasticity, alterations in nlgn expression and function that may play an important role in neuropathic pain.15 This led us to explore the possible role of nlgn1 and 2 plasticity in the setting of hyperalgesic priming. Our findings support a model wherein nlgn2 controls pathological alterations in inhibitory synapse structure and function that underlies the maintenance of hyperalgesic priming.

Nlgn2 synaptic adhesion molecules have been shown to exclusively localize to inhibitory synapses,49 to recruit gephyrin,36 which is involved in clustering of GABAARs, and to be required for the formation of functioning inhibitory synapses.9 Our observation of increased nlgn2 protein expression and increased nlgn2A mRNA strongly suggests that GABAergic inhibitory synapses increase after priming, which could increase inhibitory tone. Paradoxically, this change is accompanied by an inversion of the valence of GABAAR pharmacology, suggesting that this increased tone contributes to pain plasticity rather than alleviating it. A possible explanation for this is the maladaptive formation of inhibitory synapses whose net effect is disinhibition. Here, rather than anionic plasticity, we speculate that proliferation of inhibitory synapses on GABAergic interneurons leads to negative regulation of inhibitory circuits resulting in a net excitatory effect. This is consistent with an anti-nociceptive effect of GABAAR antagonists and a lack of change in KCC2 protein expression. Interestingly, a recent report examining changes in nlgn expression following peripheral nerve injury in rats found an upregulation of nlgn2 expression in the spinal cord that was likewise not accompanied by changes in nlgn1 or neurexin expression. Moreover, these investigators also found that nlgn2 knockdown, in their case with shRNA, led to an alleviation of mechanical hypersensitivity brought about by peripheral nerve injury yet caused mechanical hypersensitivity in sham rats.15 This is strikingly similar to our findings with the nlgn2 interfering peptide, neurolide 2. Interestingly, while the study in rats with peripheral nerve injury found an upregulation of the nlgn2(−) splice variant in the spinal cord,15 we observed an increase in nlgn2A. These 2 isoforms have differential distributions between inhibitory (nlgn2A) and excitatory (nlgn2(−)) synapses,10,15 and these disparate results between hyperalgesic priming and neuropathic models, respectively, may point to crucial differences in underlying mechanisms. Interestingly, despite differential regulation at the level of splicing, they both illustrate how targeting of nlgn2 in the spinal dorsal horn can lead to beneficial effects after peripheral injury. In the case of hyperalgesic priming, further investigation is required to understand which group of GABAergic neurons is mediating this effect and what their downstream targets are. These experiments may lead to new insights into how the transition to pathological pain occurs.

We find a dynamic regulation of nlgn expression in the spinal cord after i.t. BDNF treatment. Although nlgn2 is increased during the maintenance of hyperalgesic priming, nlgn1 was decreased in the spinal dorsal horn during the initiation of priming. Nlgn1 interacts with PSD-95,21 modulates the NMDAR to AMPAR (alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionate receptor) ratio11 and recruits NMDARs to excitatory synapses.7 Accordingly, a reduction in nlgn1 significantly reduces excitatory postsynaptic current.11 We speculate that our observation of decreased nlgn1 expression may be related to a protective homeostatic mechanisms against excitotoxicity51 or excessive network activity.50 Nevertheless, because nlgn1 expression changes were transient in the hyperalgesic priming model, we conclude that nlgn1 is unlikely to play a role in the maintenance of hyperalgesic priming and we focused our subsequent experiments on nlgn2.

Our findings add to a growing body of literature pointing to altered neuronal network behavior following the transition to a chronic pain state. We recently showed that descending dopaminergic projections from the A11 nucleus of the hypothalamus play a key role in promoting the maintenance of hyperalgesic priming although this same pathway plays no apparent role in acute mechanical hypersensitivity or pain affect.28 Dopamine D1/D5 receptors underlie this effect, again, playing a role only once hyperalgesic priming enters its maintenance phase.28 Importantly, we show here that disruption of nlgn2 in the maintenance phase of hyperalgesic priming reverses the pain promoting effects of D1/D5 agonists that are only apparent in primed animals. Likewise, disruption of nlgn2 with neurolide 2 led to a reversal in the pain inhibitory effects of a GABAA antagonist in primed animals, causing the antagonist to again act in a pronociceptive manner. These findings indicate that the neurolide 2 treatment reverts spinal pharmacology in primed mice back to a state that is observed in naive mice, suggesting a reversal of the pathological plasticity state. A similar model, termed “latent sensitization,” has been used to demonstrate that dorsal horn μ-opioid, and perhaps other G-protein-coupled receptors,33 acquire constitutive activity following peripheral inflammation. These constitutively active receptors then mask hyperalgesia that can be revealed with administration of a μ-opioid inverse agonist.12,45 Collectively, this body of work indicates that neuronal networks mediating acute pain sensitivity directly following injury may not be the same once the organism transitions to a state of pathological pain plasticity. More work is needed to explore this idea more fully; however, it would have important implications for target development and therapeutic discovery. An intriguing possibility, based on our current and previous work is that dopaminergic spinal projections control GABAergic network plasticity leading to the maintenance of a chronic pain state. Future work will explore this hypothesis in more detail.

The original description of neurolide 2 indicated that the peptide disrupts nlgn2/neurexin 1β interactions,48 but this work did not address whether neurolide 2 decreases nlgn2 protein levels. We observed a decrease in nlgn2 protein levels after treatment with neurolide 2. The mechanism through which this occurs is not known. However, chronic stress induces altered social behavior that is accompanied by decreased hippocampal nlgn2 expression. Neurolide 2 treatment mimics the effects of stress on social behaviors suggesting, consistent with our findings, that this treatment reduces nlgn2 expression in hippocampus.48 Therefore, we conclude that our experimental results with neurolide 2 are consistent with previous work using this tool to disrupt nlgn2 function.

In this study, we discovered that hyperalgesic priming induces changes to spinal GABAAR pharmacology and persistently increases nlgn2-expressing inhibitory synapses, which play a key role in maintaining the neuroplasticity mediating hyperalgesic priming. Our observations indicate that nlgn2 can be manipulated through pharmacological targeting to achieve a reversal of pathological pain plasticity. Therefore, our work gives new insight into a novel type of GABAergic plasticity in the spinal dorsal horn controlled by nlgn2.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants: R01NS065926 (T.J.P.), R01GM102575 (T.J.P.) and The University of Texas STARS program research support grant (T.J.P.).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Anseloni VCZ, Gold MS. Inflammation-induced shift in the valence of spinal GABA-A receptor-mediated modulation of nociception in the adult rat. J Pain. 2008;9:732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asiedu M, Ossipov MH, Kaila K, Price TJ. Acetazolamide and midazolam act synergistically to inhibit neuropathic pain. PAIN. 2010;148:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Asiedu MN, Mejia G, Ossipov MK, Malan TP, Kaila K, Price TJ. Modulation of spinal GABAergic analgesia by inhibition of chloride extrusion capacity in mice. J Pain. 2012;13:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asiedu MN, Mejia GL, Hubner CA, Kaila K, Price TJ. Inhibition of carbonic anhydrase augments GABAA receptor-mediated analgesia via a spinal mechanism of action. J Pain. 2014;15:395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asiedu MN, Tillu DV, Melemedjian OK, Shy A, Sanoja R, Bodell B, Ghosh S, Porreca F, Price TJ. Spinal protein kinase M zeta underlies the maintenance mechanism of persistent nociceptive sensitization. J Neurosci. 2011;31:6646–6653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6286-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blundell J, Tabuchi K, Bolliger MF, Blaiss CA, Brose N, Liu X, Südhof TC, Powell CM. Increased anxiety-like behavior in mice lacking the inhibitory synapse cell adhesion molecule neuroligin 2. Genes Brain Behav. 2009;8:114–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2008.00455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Budreck EC, Kwon OB, Jung JH, Baudouin S, Thommen A, Kim HS, Fukazawa Y, Harada H, Tabuchi K, Shigemoto R, Scheiffele P, Kim JH. Neuroligin-1 controls synaptic abundance of NMDA-type glutamate receptors through extracellular coupling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:725–730. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214718110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman CR, Casey KL, Dubner R, Foley KM, Gracely RH, Reading AE. Pain measurement: an overview. PAIN. 1985;22:1–31. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chih B, Engelman H, Scheiffele P. Control of excitatory and inhibitory synapse formation by neuroligins. Science. 2005;307:1324–1328. doi: 10.1126/science.1107470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chih B, Gollan L, Scheiffele P. Alternative splicing controls selective transsynaptic interactions of the neuroligin-neurexin complex. Neuron. 2006;51:171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chubykin AA, Atasoy D, Etherton MR, Brose N, Kavalali ET, Gibson JR, Südhof TC. Activity-dependent validation of excitatory versus inhibitory synapses by neuroligin-1 versus neuroligin-2. Neuron. 2007;54:919–931. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Corder G, Doolen S, Donahue RR, Winter MK, Jutras BL, He Y, Hu X, Wieskopf JS, Mogil JS, Storm DR, Wang ZJ, McCarson KE, Taylor BK. Constitutive mu-opioid receptor activity leads to long-term endogenous analgesia and dependence. Science. 2013;341:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1239403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coull JA, Beggs S, Boudreau D, Boivin D, Tsuda M, Inoue K, Gravel C, Salter MW, De Koninck Y. BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature. 2005;438:1017–1021. doi: 10.1038/nature04223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coull JA, Boudreau D, Bachand K, Prescott SA, Nault F, Sik A, De Koninck P, De Koninck Y. Trans-synaptic shift in anion gradient in spinal lamina I neurons as a mechanism of neuropathic pain. Nature. 2003;424:938–942. doi: 10.1038/nature01868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolique T, Favereaux A, Roca-Lapirot O, Roques V, Léger C, Landry M, Nagy F. Unexpected association of the “inhibitory” neuroligin 2 with excitatory PSD95 in neuropathic pain. PAIN. 2013;154:2529–2546. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doyon N, Prescott SA, Castonguay A, Godin AG, Kroger H, De Koninck Y. Efficacy of synaptic inhibition depends on multiple, dynamically interacting mechanisms implicated in chloride homeostasis. PLoS Comput Biol. 2011;7:e1002149. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1002149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eaton MJ, Plunkett JA, Karmally S, Martinez MA, Montanez K. Changes in GAD-and GABA-immunoreactivity in the spinal dorsal horn after peripheral nerve injury and promotion of recovery by lumbar transplant of immortalized serotonergic precursors. J Chem Neuroanat. 1998;16:57–72. doi: 10.1016/s0891-0618(98)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gagnon M, Bergeron MJ, Lavertu G, Castonguay A, Tripathy S, Bonin RP, Perez-Sanchez J, Boudreau D, Wang B, Dumas L, Valade I, Bachand K, Jacob-Wagner M, Tardif C, Kianicka I, Isenring P, Attardo G, Coull JA, De Koninck Y. Chloride extrusion enhancers as novel therapeutics for neurological diseases. Nat Med. 2013;19:1524–1528. doi: 10.1038/nm.3356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ibuki T, Hama AT, Wang XT, Pappas GD, Sagen J. Loss of GABA-immunoreactivity in the spinal dorsal horn of rats with peripheral nerve injury and promotion of recovery by adrenal medullary grafts. Neuroscience. 1996;76:845–858. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(96)00341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichtchenko K, Nguyen T, Südhof TC. Structures, alternative splicing, and neurexin binding of multiple neuroligins. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2676–2682. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.5.2676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Irie M, Hata Y, Takeuchi M, Ichtchenko K, Toyoda A, Hirao K, Takai Y, Rosahl TW, Sudhof TC. Binding of neuroligins to PSD-95. Science. 1997;277:1511–1515. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5331.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Josan JS, Vagner J, Handl HL, Sankaranarayanan R, Gillies RJ, Hruby VJ. Solid-phase synthesis of heterobivalent ligands targeted to melanocortin and cholecystokinin receptors. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2008;14:293–300. doi: 10.1007/s10989-008-9150-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaila K, Price TJ, Payne JA, Puskarjov M, Voipio J. Cation-chloride cotransporters in neuronal development, plasticity and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:637–654. doi: 10.1038/nrn3819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kandasamy R, Price TJ. The pharmacology of nociceptor priming. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2015;227:15–37. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-46450-2_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kerr BJ, Bradbury EJ, Bennett DL, Trivedi PM, Dassan P, French J, Shelton DB, McMahon SB, Thompson SW. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor modulates nociceptive sensory inputs and NMDA-evoked responses in the rat spinal cord. J Neurosci. 1999;19:5138–5148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-12-05138.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khirug S, Ahmad F, Puskarjov M, Afzalov R, Kaila K, Blaesse P. A single seizure episode leads to rapid functional activation of KCC2 in the neonatal rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2010;30:12028–12035. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3154-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HY, Jun J, Wang J, Bittar A, Chung K, Chung JM. Induction of long-term potentiation and long-term depression is cell-type specific in the spinal cord. PAIN. 2015;156:618–625. doi: 10.1097/01.j.pain.0000460354.09622.ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kim JY, Tillu DV, Quinn TL, Mejia GL, Shy A, Asiedu MN, Murad E, Schumann AP, Totsch SK, Sorge RE, Mantyh PW, Dussor G, Price TJ. Spinal dopaminergic projections control the transition to pathological pain plasticity via a d1/d5-mediated mechanism. J Neurosci. 2015;35:6307–6317. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3481-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langford DJ, Bailey AL, Chanda ML, Clarke SE, Drummond TE, Echols S, Glick S, Ingrao J, Klassen-Ross T, Lacroix-Fralish ML, Matsumiya L, Sorge RE, Sotocinal SG, Tabaka JM, Wong D, van den Maagdenberg AM, Ferrari MD, Craig KD, Mogil JS. Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nat Methods. 2010;7:447–449. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lavertu G, Cote SL, De Koninck Y. Enhancing K-Cl co-transport restores normal spinothalamic sensory coding in a neuropathic pain model. Brain. 2014;137(pt 3):724–738. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee KY, Prescott SA. Chloride dysregulation and inhibitory receptor blockade yield equivalent disinhibition of spinal neurons yet are differentially reversed by carbonic anhydrase blockade. PAIN. 2015;156:2431–2437. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2- DDCT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marvizon JC, Walwyn W, Minasyan A, Chen W, Taylor BK. Latent sensitization: a model for stress-sensitive chronic pain. Curr Protoc Neurosci. 2015;71:9.50.1–9.50.14. doi: 10.1002/0471142301.ns0950s71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Melemedjian OK, Tillu DV, Asiedu MN, Mandell EK, Moy JK, Blute VM, Taylor CJ, Ghosh S, Price TJ. BDNF regulates atypical PKC at spinal synapses to initiate and maintain a centralized chronic pain state. Mol Pain. 2013;9:12. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-9-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nijs J, Meeus M, Versijpt J, Moens M, Bos I, Knaepen K, Meeusen R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a driving force behind neuroplasticity in neuropathic and central sensitization pain: a new therapeutic target? Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2015;19:565–576. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2014.994506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poulopoulos A, Aramuni G, Meyer G, Soykan T, Hoon M, Papadopoulos T, Zhang M, Paarmann I, Fuchs C, Harvey K. Neuroligin 2 drives postsynaptic assembly at perisomatic inhibitory synapses through gephyrin and collybistin. Neuron. 2009;63:628–642. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prescott SA. Synaptic inhibition and disinhibition in the spinal dorsal horn. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2015;131:359–383. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Price TJ, Cervero F, De Koninck Y. Role of cation-chloride-cotransporters (CCC) in pain and hyperalgesia. Curr Top Med Chem. 2005;5:547–555. doi: 10.2174/1568026054367629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Price TJ, Cervero F, Gold MS, Hammond DL, Prescott SA. Chloride regulation in the pain pathway. Brain Res Rev. 2009;60:149–170. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2008.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price TJ, Inyang KE. Commonalities between pain and memory mechanisms and their meaning for understanding chronic pain. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2015;131:409–434. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Price TJ, Prescott SA. Inhibitory regulation of the pain gate and how its failure causes pathological pain. PAIN. 2015;156:789–792. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reichling DB, Green PG, Levine JD. The fundamental unit of pain is the cell. PAIN. 2013;154(suppl 1):S2–S9. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reichling DB, Levine JD. Critical role of nociceptor plasticity in chronic pain. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:611–618. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sussman JL, Harel M, Frolow F, Oefner C, Goldman A, Toker L, Silman I. Atomic structure of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: a prototypic acetylcholine-binding protein. Science. 1991;253:872–879. doi: 10.1126/science.1678899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Taylor BK, Corder G. Endogenous analgesia, dependence, and latent pain sensitization. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2014;20:283–325. doi: 10.1007/7854_2014_351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tillu DV, Hassler SN, Burgos-Vega CC, Quinn TL, Sorge RE, Dussor G, Boitano S, Vagner J, Price TJ. Protease-activated receptor 2 activation is sufficient to induce the transition to a chronic pain state. PAIN. 2015;156:859–867. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vagner J, Xu L, Handl HL, Josan JS, Morse DL, Mash EA, Gillies RJ, Hruby VJ. Heterobivalent ligands crosslink multiple cell-surface receptors: the human melanocortin-4 and delta-opioid receptors. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2008;47:1685–1688. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Kooij MA, Fantin M, Kraev I, Korshunova I, Grosse J, Zanoletti O, Guirado R, Garcia-Mompo C, Nacher J, Stewart MG, Berezin V, Sandi C. Impaired hippocampal neuroligin-2 function by chronic stress or synthetic peptide treatment is linked to social deficits and increased aggression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39:1148–1158. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Varoqueaux F, Jamain S, Brose N. Neuroligin 2 is exclusively localized to inhibitory synapses. Eur J Cell Biol. 2004;83:449–456. doi: 10.1078/0171-9335-00410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vitureira N, Goda Y. Cell biology in neuroscience: the interplay between Hebbian and homeostatic synaptic plasticity. J Cell Biol. 2013;203:175–186. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201306030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang H, Yu SW, Koh DW, Lew J, Coombs C, Bowers W, Federoff HJ, Poirier GG, Dawson TM, Dawson VL. Apoptosis-inducing factor substitutes for caspase executioners in NMDA-triggered excitotoxic neuronal death. J Neurosci. 2004;24:10963–10973. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3461-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yowtak J, Wang J, Kim HY, Lu Y, Chung K, Chung JM. Effect of antioxidant treatment on spinal GABA neurons in a neuropathic pain model in the mouse. PAIN. 2013;154:2469–2476. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhou LJ, Zhong Y, Ren WJ, Li YY, Zhang T, Liu XG. BDNF induces late-phase LTP of C-fiber evoked field potentials in rat spinal dorsal horn. Exp Neurol. 2008;212:507–514. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]