Abstract

In the United States (US), a parent’s health insurance status affects their children’s access to health care making it critically important to examine trends in coverage for both children and parents. To gain a better understanding of these health insurance trends, we assessed the coverage status for both children and their parents over an 11-year time period (1998–2008). We conducted secondary analysis of data from the nationally-representative Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. We examined frequency distributions for full-year child/parent insurance coverage status by family income, conducted Chi-square tests of association to assess significant differences over time, and explored factors associated with full-year insurance coverage status in 1998 and in 2008 using logistic regression. When considering all income groups together, the group with both child and parent insured decreased from 72.4 % in 1998 to 67.2 % in 2008. When stratified by income, the percentage of families with an insured child, but an uninsured parent increased for low-income families from 12.4 to 25.1 % and from 3.8 to 7.1 % for middle-income families when comparing 1998–2008. In regression analyses, family income remained the strongest characteristic associated with a lack of full-year health insurance. As future policy reforms take shape, it will be important to look beyond children’s coverage patterns to assess whether gains have been made in overall family coverage.

Keywords: Health insurance coverage, Children’s health, Access to care, Family health, Uninsured

Introduction

Both lack of health insurance coverage and health insurance coverage discontinuity are associated with decreased access to health care for families, often resulting in unmet medical and prescription drug needs and a lack of recommended preventive health services [1–7]; all leading to generally poorer health [8, 9]. Those without health insurance coverage also have higher mortality rates than those with private health insurance [10]. The most common source of health insurance in the US is employer-sponsored coverage. Between 2000 and 2008, fewer employers in the United States (US) offered health insurance to families: the rate of employer-sponsored coverage decreased 6 % during this time period. For families still able to purchase coverage through employers, health insurance premiums increased steadily averaging 113 % between 2001 and 2011 [11, 12]. Due to these changes in access to coverage, millions of US families went without any health insurance while others had mixed coverage status within the family (i.e. parent(s) had insurance/child did not; child had insurance/parent(s) did not), or had difficulty attaining continuous coverage [13–15].

The increasing difficulty US families have had obtaining stable health insurance coverage has fueled action at the federal level. In 1997, legislation was passed to create the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which increased federal and state funding for children’s public health insurance [16]. Once CHIP was implemented, health insurance rates improved for children in families earning less than 400 % of the federal poverty level (FPL) [17]. CHIP was reauthorized in 2009, which expands public health insurance coverage for up to 4.1 million additional children by 2013 [18], and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) of 2010 has additional provisions to extend coverage to a greater number of children [16, 19].

While health insurance coverage for children is an important factor in their access to health care, gains in children’s coverage reflect only a part of the family health insurance equation: a positive relationship also exists between parents’ coverage and their child’s health insurance status. Compared to children with uninsured parents, children with insured parents are more likely to maintain stable coverage and to receive recommended health care services [7, 20–22]. While the CHIP has increased coverage for children, public insurance has been largely unavailable for non-disabled adults, regardless of income level. One study based on Current Population Survey data found 33.8 % of children under age 18 were covered by Medicaid versus a mere 9.9 % of adults in 2009 [23]. The PPACA has the potential to increase the availability of insurance for children as well as adults through health insurance exchanges and increased eligibility for Medicaid programs, but these gains have yet to be made [16, 19].

Past studies have looked at patterns of health insurance coverage for children or coverage for adults separately, but there is limited information about trends in family coverage [17, 24, 25]. In order to attain a true picture of access to health care for children, it is important to simultaneously understand trends in health insurance coverage for both children and their parents. Our study linked children and their parents in a nationally-representative dataset, from 1998 through 2008, to examine and compare the trends in health insurance coverage for both children and parents. Since health insurance status is also associated with income [26, 27] and it is likely that different income groups may have experienced different trends over time, we also looked at these trends stratified by income.

Methods

Data

This analysis used data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey-Household Component (MEPS-HC), which collects information from a subsample of households from the National Health Interview Survey and utilizes a stratified and clustered random sample with weights that produce nationally representative estimates for the civilian, non-institutionalized US population [28, 29]. MEPS-HC selects a new panel of respondents each year, and data is collected from each panel 5 times over a 2-year period. Each annual public use file contains data from two overlapping panels of the MEPS (e.g. the 2008 file contains data from the second year of panel 12 and the first year of panel 13). Each year of MEPS-HC data constitutes a nationally representative sample and pooling the data produces average annual estimates. MEPS survey design and methodology are reported elsewhere [30–33]. We combined yearly data for an 11-year period (1998–2008) from annual public use files [34].

We included children aged 0–17 years, with responses to one full year of the survey (N = 97,868). We linked each child to one or both parents and then constructed child/parent health insurance status variables. Children who could be linked to at least one biological, adopted, and/or step-parent residing in the same household were included (MEPS does not include variables for linking foster parents or non-parent guardians) (n = 94,675). We narrowed this group further to include only child and parent pairs for whom health insurance information was available for the full year; resulting in a final sample size of 93,419, weighted to a yearly average of about 70 million children [35].

Variables

We constructed child/parent variables to represent full-year insurance coverage status for child and parent pairs including: (1) child insured/parent insured, (2) child insured/parent not insured, (3) child not insured/parent insured, and (4) child not insured/parent not-insured [36]. MEPS-HC assesses insurance coverage status monthly. We utilized each person’s monthly coverage status to create full-year insurance variables. In this study, to be considered insured for the full-year, the child and/or parents had to report having at least 1 day of health insurance coverage in each of 12 months of the calendar year. For ‘parent’ insurance status, we considered parents insured if at least one parent was insured for the full-year. Parents were uninsured if the sole parent (in single parent households) or both parents were uninsured for some or all of the year. We based our household income stratifications on MEPS classifications, defining low-income as <200 % FPL (this combines the MEPS ‘poor’, ‘near poor’, and ‘low-income’ categories); middle-income as 200–<400 % FPL, and high-income as ≥400 % FPL [36]. We combined the MEPS poor, near poor, and low-income groups together to represent low-income for this study as many public health insurance programs and other charitable programs consider households earning less than 200 % FPL eligible for free or reduced-cost services [37].

Other demographic characteristics examined included child’s age, region of residence, health status (as perceived by the reporting parent), combined race/ethnicity, family composition (one parent in the household vs. two parents in the household), parent education, and parent employment. Note that race was characterized dissimilarly in different years of the MEPS. From 1998 to 2001, race was recorded as being American Indian, Aleut or Eskimo, Asian or Pacific Islander, black, or white; from 2002 to 2008, race categories were changed to white only, black only, American Indian/ Alaska Native only, Asian only, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander only, or multiple races. Therefore, our race/ethnicity categories of white/non-Hispanic, non-white/non-Hispanic, and Hispanic/any race are not directly comparable over time [e.g. in 1998 those recorded as being white/non-Hispanic could have been white plus another (unrecorded) race but not Hispanic, while in 2008, the category corresponds to those who were only white and not Hispanic].

Analysis

We examined frequency distributions for full-year child/ parent insurance coverage status stratified by income. We conducted Chi-square tests to assess significant differences in insurance status between 1998 and 2008 overall and by income level. We used logistic regression to explore additional demographic characteristics associated with health insurance coverage status in 1998 and in 2008. We reported measures of association from regression modeling as relative risks [38]. Sampling stratification variables and weights were used to account for the complex sample design of the survey, and all analyses were conducted using SUDAAN software, version 10.0.1 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC). This study was considered exempt by the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Review Board because MEPS data is publicly available.

Results

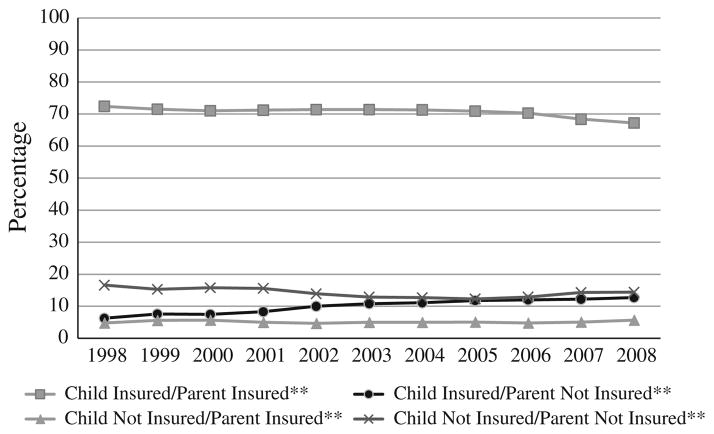

When considering all income groups together over the 11-year study period (1998–2008), the child insured and parent not insured group showed the most change, increasing steadily from 6.3 to 12.7 % (Fig. 1). The group with both child and parent insured decreased from 72.4 to 67.2 %, with the most notable drop between 2006 and 2008. The other two groups (child not insured/parent insured and child not insured/parent not insured) saw little change. Also notable in Fig. 1 is the consistent percentage of families with uninsured children and insured parents.

Fig. 1.

Child and parent full-year health insurance coverage status, all income levels, 1998–2008. Source: Medical expenditures panel survey-household component (MEPS-HC), 1998–2008. Full-year insurance status: MEPS-HC assesses insurance coverage status monthly, so we utilized each person’s monthly coverage status to create full-year insurance variables. To be considered insured for the full-year, the child and/or parent(s) had to report having at least 1 day of health insurance coverage in each of 12 months of the calendar year. **For ‘parent’ insurance status, we considered parent(s) insured if at least one parent was insured for the full-year. Parent(s) were uninsured if the sole parent (in single parent households) or both parents were uninsured for some or all of the year

When stratified by income as shown in Table 1, more drastic differences in coverage experienced by low- and middle-income US families between 1998 and 2008 become evident. This stratification reveals persistent disparities in coverage patterns between income groups. Most striking for the low-income group is the increasing percentage of families with child insured/parent not insured (from 12.4 to 25.1 %). This coincides with a decrease in low-income families with both child and parent insured (from 54.5 to 48.6 %) and both child and parent uninsured (from 26.3 to 21.4 %). Middle-income families saw a decrease in the percentage of those with both child and parent insured (from 78.4 to 72.9 %); however, the percentage of families with both child and parent not insured showed some early declines but ultimately remained the same over the entire time period.

Table 1.

Child and parent full-year health insurance status patterns, by income level, 1998 versus 2008

| Full-year* health insurance status | %

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1998 | 2008 | ||

| Low-income (< 200 % FPL) | |||

| Child insured/parent insured** | 54.5 | 48.6 | ^ |

| Child insured/parent not insured** | 12.4 | 25.1 | + |

| Child not insured/parent insured** | 6.8 | 4.9 | ^ |

| Child not insured/parent not insured** | 26.3 | 21.4 | ^ |

| Middle-income (200–400 % FPL) | |||

| Child insured/parent insured** | 78.4 | 72.9 | ^ |

| Child insured/parent not insured** | 3.8 | 7.1 | ^ |

| Child not insured/parent insured** | 4.6 | 7.0 | ^ |

| Child not insured/parent not insured** | 13.2 | 13.0 | |

| High-income (≥400 % FPL) | |||

| Child insured/parent insured** | 89.9 | 87.6 | |

| Child insured/parent not insured** | # | # | NA |

| Child not insured/parent insured** | # | 5.3 | NA |

| Child not insured/parent not insured** | 7.1 | 5.8 | |

Source: Medical expenditures panel survey-household component, 1998–2008

FPL Federal Poverty Level

Full-year insurance status: MEPS-HC assesses insurance coverage status monthly, so we utilized each person’s monthly coverage status to create full-year insurance variables. To be considered insured for the full-year, the child and/or parents had to report having some health insurance coverage in all 12 months of the calendar year

For ‘parent’ insurance status, we considered parents insured if at least one parent was insured for the full-year. Parents were uninsured if the sole parent (in single parent households) or both parents were uninsured for some or all of the year

Estimates unreliable due to small number (N < 30)

P value < 0.001 for comparisons between 1998 and 2008

P value < 0.05 for comparisons between 1998 and 2008

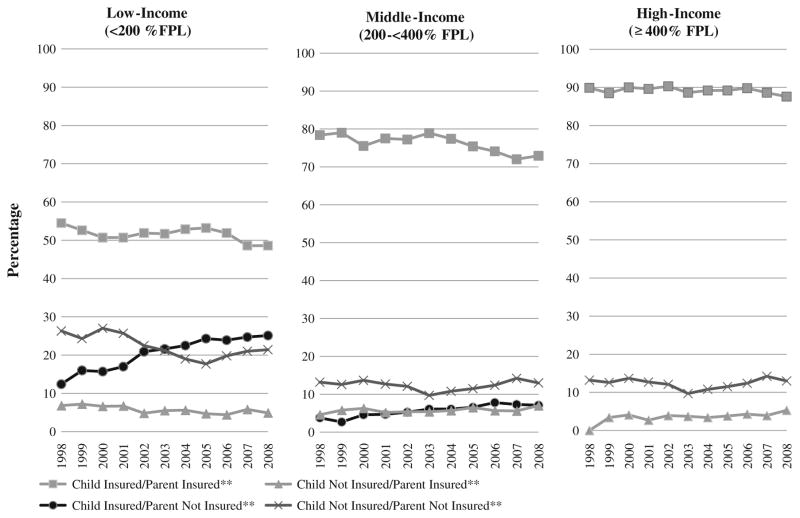

In addition to the declining percentage of coverage for both children and parents in low- and middle-income families, Fig. 2 illuminates the persistent disparities between income groups. In comparison to the large percentage of high-income children and parents with insurance coverage, the percentage of low-income families with both child and parent covered dipped below 50 % by 2008. Conversely, the majority of low-income families did not have health insurance coverage for a child and/or a parent in 2008 as compared to the small minority of high-income families.

Fig. 2.

Child and parent full-year health insurance coverage status, by income level, 1998–2008. Source medical expenditures panel survey-household component (MEPS-HC), 1998–2008. FPL federal poverty level. Full-year insurance status: MEPS-HC assesses insurance coverage status monthly, so we utilized each person’s monthly coverage status to create full-year insurance variables. To be considered insured for the full-year, the child and/or parent(s) had to report having at least 1 day of health insurance coverage in each of 12 months of the calendar year. **For ‘parent’ insurance status, we considered parent(s) insured if at least one parent was insured for the full-year. Parent(s) were uninsured if the sole parent (in single parent households) or both parents were uninsured for some or all of the year. #Child insured/parent not insured group estimates unreliable in high-income families due to small number (N <30). Accompanying detail can be found in “Appendix”

Several characteristics were significantly associated with full-year health insurance coverage for children and their parents in both 1998 and 2008. The most significant association was family income; those making <200 % FPL were less likely to have both child and parent insured for the full-year than those with family incomes ≥400 % FPL [adjusted relative risk (aRR) 0.69, confidence interval (CI): 0.63–0.74 in 1998; aRR 0.66, CI: 0.61–0.70 in 2008]. Additional characteristics consistently associated with a lack of insurance include living in the South, being Hispanic, having only one parent in the household, and parents with <12 years of education. Parent employment was initially found to be non-significant in multiple logistic regression (indicating multi-collinearity among the parent characteristics), but when included as part of an interaction term, was found to be an effect modifier of the relationship between full-year child/parent health insurance coverage status and parent education and family composition. Of note, few changes were seen when comparing significant associations in 1998 versus 2008 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations of family characteristics with both child and parent having full-year* insurance, 1998 versus 2008

| 1998

|

2008

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted RR (95 % CI) | Adjusted RR (95 % CI) | Unadjusted RR (95 % CI) | Adjusted RR (95 % CI) | |

| Family income | ||||

| < 200 % FPL | 0.60 (0.56–0.65) | 0.69 (0.63–0.74) | 0.56 (0.51–0.60) | 0.66 (0.61–0.70) |

| 200– < 400 % FPL | 0.87 (0.83–0.91) | 0.88 (0.84–0.92) | 0.83 (0.79–0.88) | 0.85 (0.80–0.90) |

| ≥400 % FPL | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Age | ||||

| 0–4 | 0.91 (0.86–0.97) | 0.96 (0.90–1.01) | 0.99 (0.93–1.05) | 1.02 (0.97–1.09) |

| 5–9 | 0.93 (0.88–0.99) | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 1.03 (0.97–1.09) | 1.06 (0.99–1.12) |

| 10–13 | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | 1.01 (0.96–1.05) | 1.05 (0.99–1.10) | 1.06 (1.00–1.11) |

| 14–17 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Midwest | 0.96 (0.90–1.04) | 0.94 (0.87–1.02) | 0.95 (0.88–1.02) | 0.95 (0.88–1.02) |

| South | 0.82 (0.76–0.88) | 0.85 (0.79–0.90) | 0.80 (0.73–0.87) | 0.83 (0.77–0.90) |

| West | 0.87 (0.80–0.95) | 0.93 (0.86–1.00) | 0.88 (0.82–0.95) | 0.95 (0.88–1.04) |

| Health status | ||||

| Excellent/very good/good | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Fair/poor | 0.82 (0.68–0.97) | 0.94 (0.83–1.07) | 0.95 (0.81–1.10) | 1.05 (0.94–1.18) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Non-white, non-Hispanic | 0.92 (0.86–0.99) | 1.06 (1.00–1.12) | 0.90 (0.86–0.95) | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) |

| Hispanic, any race | 0.65 (0.59–0.73) | 0.86 (0.79–0.93) | 0.61 (0.55–0.69) | 0.80 (0.73–0.87) |

| Family composition | ||||

| One parent in household | 0.79 (0.75–0.85) | 0.90 (0.85–0.95) | 0.75 (0.70–0.81) | + |

| Two parents in household | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Parent education | ||||

| ≥12 years | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| < 12 years | 0.62 (0.56–0.69) | + | 0.51 (0.44–0.59) | + |

| Parent employment | ||||

| At least one parent employed | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Parent(s) unemployed | 0.82 (0.75–0.90) | + | 0.72 (0.65–0.81) | + |

| Parent education × parent employment (interaction) | ||||

| At least one parent employed | ||||

| Parent education ≥12 years | ^ | 1.00 | ^ | 1.00 |

| Parent education < 12 years | ^ | 0.77 (0.69–0.87) | ^ | 0.74 (0.64–0.85) |

| Parent(s) unemployed | ||||

| Parent education ≥12 years | ^ | 1.00 | ^ | 1.00 |

| Parent education < 12 years | ^ | 1.15 (1.02–1.29) | ^ | 1.03 (0.89–1.19) |

| Family composition × parent employment (interaction) | ||||

| At least one parent employed | ||||

| One parent in household | ^ | # | ^ | 0.85 (0.79–0.92) |

| Two parents in household | ^ | # | ^ | 1.00 |

| Parent(s) unemployed | ||||

| One parent in household | ^ | # | ^ | 1.05 (0.85–1.31) |

| Two parents in household | ^ | # | ^ | 1.00 |

Source: Medical expenditures panel survey-household component (MEPS-HC), 1998–2008

Bold indicates RR significant at p < 0.05

RR relative risk; CI confidence interval, FPL federal poverty level

Full-year insurance status: MEPS-HC assesses insurance coverage status monthly, so we utilized each person’s monthly coverage status to create full-year insurance variables. To be considered insured for the full-year, the child and/or parent(s) had to report having at least 1 day of health insurance coverage in each of 12 months of the calendar year

Main effects for variables that are components of interaction terms are not estimated

Interaction terms not included in unadjusted regression models

Family composition × parent employment interaction was not significant and therefore was not included in the final regression model for 1998

Discussion

When considering patterns of health insurance coverage for US children and their parents from 1998 through 2008, there was a slow and steady decline in the percentage of those with full-year coverage for a child and at least one parent. Over the same time period, there was a steady increase in the percentage of families with an insured child but no coverage for their parents. When stratified by income, the changes in health insurance coverage patterns among low- and middle-income families were more dramatic as compared to high-income families. Most notable were the substantial decreases in the percentage of low-and middle-income families with both a child and parent insured, a simultaneous increase in those who had an insured child with an uninsured parent, and fairly consistent percentages where both child and parent were uninsured.

Our findings confirm previous studies that have shown children’s health insurance coverage rates increased after the passage of CHIP [39–41], though rates of increase had leveled off by the end of the past decade [17]. Our study adds to this body of knowledge by giving perspective on what has happened to parents during this same time period: although children have gained health insurance, parents have lost coverage. These findings are concerning because (1) lack of insurance leads to decreased ability for families to access health care [42–44], and (2) children’s health insurance coverage status can be negatively impacted by their parents’ lack of coverage [20–22, 45]. One study found parents’ with the fewest months of coverage had the highest odds of having uninsured children as compared to parents’ with continuous coverage [45]. Thus, despite gains in children’s health insurance, the erosion of parents’ coverage may still lead to unmet health care needs for both children and their parents. Since the health insurance status of children is often associated with that of their parents, we can expect disparities to persist until all family members receive coverage.

While our findings also show that several demographic characteristics are significantly associated with a lack of full-year health insurance, the nature of these associations have not changed much from 1998 to 2008, suggesting that there may be factors other than demographics that are contributing to the downward trends in full-year health insurance coverage.

Families will likely have increasing access to insurance coverage after full implementation of the PPACA. For example, the PPACA calls for (by 2014) expanding Medicaid to cover all Americans making less than 133 % FPL, creating state health insurance exchanges to allow those without insurance offered through their employers to buy it directly, and implementing tax credits to help middle class families buy insurance [19, 46]. Once these policies are fully implemented, some experts predict that uninsurance rates will drop by 50–70 % for adults and 40 % for children [47, 48]. Medicaid expansions may reverse the rising trend of low-income families with uninsured parents, and CHIP expansions may help more middle-class children gain insurance coverage. Since the Supreme Court ruling upheld the Medicaid expansion, but not enforcement for states to participate in the expansion, disparities in adult health insurance coverage may continue [49–51]. Thus, even with full implementation of the PPACA we may not see increases in health insurance rates among middle-income parents unless coverage becomes more affordable or a public option is made available to them.

This study highlights an alarming downward trend in health insurance coverage for US families. It also has relevance to future evaluations of how coverage patterns might change through PPACA implementation. Not only do study findings provide important historical comparisons, but our methods for assessing coverage patterns among US children and their parents will be important to assess future trends. It is essential to broaden studies of insurance coverage beyond children’s coverage in order get a more complete picture of how policies are affecting children and their families. Additionally, it is important to consider the relationship between changes in coverage and income level.

Limitations

Our analyses were limited by the existing data, and as with all studies that rely on self-report, response bias remains a possibility. We measured health insurance status changes over time, but MEPS data do not provide explanations about why these changes have occurred. Finally, this study does not account for state-level differences in policies which have expanded and contracted public health insurance to the uninsured, nor does it account for specific economic trends.

Conclusions

From 1998 through 2008, low- and middle-income children experienced an increase in health insurance coverage, but coverage for their parents decreased. Measuring success by patterns of children’s coverage in isolation misses persistent disparities in family coverage. Further, insurance coverage inequalities between low-income and high-income families have persisted despite efforts to increase spending on public coverage. Continued disparities and a downward trend in coverage for entire families will negatively impact children’s health. These findings support continued efforts to achieve policies that ensure better access to health insurance coverage for all.

Acknowledgments

This study was financially supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) (1 R01 HS018569) and the Oregon Health & Science University Department of Family Medicine. The funding agencies had no involvement in the design and conduct of the study; analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. AHRQ collects and manages the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Appendix

See Table 3.

Table 3.

Child and parent full-year* health insurance status patterns, by income level, 1998 through 2008

| Full-year insurance status* | Years | < 200 % FPL Unweighted N (%) |

200– < 400 FPL Unweighted N (%) |

≥400 FPL Unweighted N (%) |

Total Unweighted N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child insured/parent insured** | 1998 | 1,688 (54.5) | 1,489 (78.4) | 1,039 (89.9) | 4,216 (72.4) |

| 1999 | 1,484 (52.6) | 1,529 (79.0) | 1,222 (88.5) | 4,235 (71.5) | |

| 2000 | 1,419 (50.7) | 1,520 (75.5) | 1,280 (90.0) | 4,219 (71.0) | |

| 2001 | 2,022 (50.7) | 2,090 (77.5) | 1,642 (89.6) | 5,754 (71.2) | |

| 2002 | 2,605 (51.9) | 2,402 (77.2) | 1,781 (90.3) | 6,788 (71.4) | |

| 2003 | 2,636 (51.7) | 1,852 (78.9) | 1,428 (88.6) | 5,916 (71.4) | |

| 2004 | 2,622 (52.9) | 1,687 (77.4) | 1,460 (89.2) | 5,769 (71.3) | |

| 2005 | 2,522 (53.2) | 1,705 (75.4) | 1,458 (89.2) | 5,685 (70.9) | |

| 2006 | 2,411 (51.9) | 1,672 (74.1) | 1,471 (89.8) | 5,554 (70.3) | |

| 2007 | 2,029 (48.6) | 1,532 (72.0) | 1,341 (88.6) | 4,902 (68.4) | |

| 2008 | 2,305 (48.6) | 1,655 (72.9) | 1,265 (87.6) | 5,225 (67.2) | |

| Child insured/parent not insured** | 1998 | 461 (12.4) | 88 (3.8) | # | 561 (6.3) |

| 1999 | 500 (16.0) | 69 (2.7) | # | 594 (7.6) | |

| 2000 | 537 (15.7) | 98 (4.6) | # | 651 (7.5) | |

| 2001 | 767 (17.0) | 152 (4.7) | # | 949 (8.3) | |

| 2002 | 1,232 (20.9) | 211 (5.3) | # | 1,476 (10.0) | |

| 2003 | 1,322 (21.6) | 232 (6.1) | # | 1,585 (10.8) | |

| 2004 | 1,371 (22.5) | 176 (6.1) | # | 1,569 (11.1) | |

| 2005 | 1,431 (24.3) | 189 (6.6) | # | 1,641 (11.8) | |

| 2006 | 1,361 (23.9) | 222 (7.8) | # | 1,612 (12.0) | |

| 2007 | 1,208 (24.7) | 180 (7.3) | # | 1,413 (12.2) | |

| 2008 | 1,407 (25.1) | 179 (7.1) | # | 1,619 (12.7) | |

| Child not insured/parent insured** | 1998 | 242 (6.8) | 123 (4.6) | # | 393 (4.8) |

| 1999 | 230 (7.2) | 148 (5.8) | 50 (3.4) | 428 (5.6) | |

| 2000 | 180 (6.6) | 122 (6.3) | 57 (4.1) | 359 (5.7) | |

| 2001 | 273 (6.7) | 156 (5.2) | 50 (2.7) | 479 (5.0) | |

| 2002 | 260 (4.8) | 200 (5.4) | 80 (3.9) | 540 (4.7) | |

| 2003 | 304 (5.5) | 136 (5.4) | 69 (3.7) | 509 (5.0) | |

| 2004 | 287 (5.6) | 134 (5.7) | 52 (3.4) | 473 (5.0) | |

| 2005 | 225 (4.7) | 163 (6.5) | 64 (3.8) | 542 (5.1) | |

| 2006 | 220 (4.4) | 142 (5.7) | 79 (4.3) | 441 (4.8) | |

| 2007 | 228 (5.8) | 130 (5.6) | 63 (3.9) | 421 (5.1) | |

| 2008 | 241 (4.9) | 160 (7.0) | 69 (5.3) | 470 (5.7) | |

| Child not insured/parent not insured** | 1998 | 920 (26.3) | 314 (13.2) | 106 (7.1) | 1,340 (16.6) |

| 1999 | 884 (24.3) | 297 (12.6) | 101 (6.5) | 1,282 (15.3) | |

| 2000 | 962 (27.0) | 360 (13.7) | 83 (4.8) | 1,405 (15.8) | |

| 2001 | 1,116 (25.7) | 401 (12.7) | 116 (6.3) | 1,633 (15.6) | |

| 2002 | 1,311 (22.5) | 437 (12.1) | 107 (4.6) | 1,855 (13.9) | |

| 2003 | 1,183 (21.2) | 283 (9.7) | 106 (5.9) | 1,572 (12.9) | |

| 2004 | 1,146 (19.0) | 299 (10.8) | 101 (6.3) | 1,546 (12.7) | |

| 2005 | 1,033 (17.7) | 310 (11.5) | 104 (5.9) | 1,447 (12.3) | |

| 2006 | 1,120 (19.8) | 337 (12.4) | 87 (4.7) | 1,544 (12.9) | |

| 2007 | 984 (21.0) | 332 (14.2) | 101 (6.1) | 1,417 (14.3) | |

| 2008 | 1,080 (21.4) | 304 (13.0) | 96 (5.8) | 1,480 (14.4) |

Source: Medical expenditures panel survey-household component (MEPS-HC), 1998–2008

FPL federal poverty level

Full-year insurance status: MEPS-HC assesses insurance coverage status monthly, so we utilized each person’s monthly coverage status to create full-year insurance variables. To be considered insured for the full-year, the child and/or parents had to report having some health insurance coverage in all 12 months of the calendar year

For ‘parent’ insurance status, we considered parents insured if at least one parent was insured for the full-year. Parents were uninsured if the sole parent (in single parent households) or both parents were uninsured for some or all of the year

Estimates unreliable due to small number (N < 30)

Footnotes

Conflict of interest We have no financial conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Heather Angier, Email: angierh@ohsu.edu, Department of Family Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 Sam Jackson Rd, Mail Code FM, Portland, OR 97239, USA.

Jennifer E. DeVoe, Email: devoej@ohsu.edu, Department of Family Medicine, Oregon Health & Science, University and OCHIN, Inc, 3181 Sam Jackson Rd, Mail Code FM, Portland, OR 97239, USA

Carrie Tillotson, Email: tillotso@ohsu.edu, Department of Family Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 Sam Jackson Rd, Mail Code FM, Portland, OR 97239, USA.

Lorraine Wallace, Email: Lorraine.wallace@osumc.edu, Department of Family Medicine, The Ohio State University, 277 Northwood-High Building, 2231 North High Street, Columbus, OH 43201, USA.

Rachel Gold, Email: Rachel.gold@kpchr.org, Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente NW, 3800 N. Interstate, Portland, OR 97227, USA.

References

- 1.Cassedy A, Fairbrother G, Newacheck PW. The impact of insurance instability on children’s access, utilization, and satisfaction with health care. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2008;8(5):321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogbuanu C, Goodmand D, Kahn K, Noggle B, Long C, Bagchi S, et al. Factors associated with parent report of access to care and the quality of care received by children 4 to 17 years of age in Georgia. Maternal and Child Health. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-1002-2. Epub March 31, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kenney G. The impacts of the State Children’s Health Insurance Program on children who enroll: Findings from ten states. Health Services Research. 2007;42(4):1520–1543. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00707.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudano JJ, Baker DW. Intermittent lack of health insurance coverage and use of preventive services. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(1):130–137. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.1.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill SC. Individual insurance and access to care. Inquiry. 2011;48(2):155–168. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_48.02.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saver BG, Peterfreund N. Insurance, income, and access to ambulatory care in King County, Washington. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83(11):1583–1588. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.11.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dombkowski KJ, Lantz PM, Freed GL. Role of health insurance and a usual source of medical care in age-appropriate vaccination. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94(6):960–966. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McWilliams JM. Health consequences of uninsurance among adults in the United States: Recent evidence and implications. Milbank Quarterly. 2009;87(2):443–494. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00564.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franks P, Clancy CM, Gold MR, Nutting PA. Health insurance and subjective health status: Data from the 1987 National Medical Expenditure survey. American Journal of Public Health. 1993;83(9):1295–1299. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.9.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilper AP, Woolhandler S, Lasser KE, McCormick D, Bor DH, Himmelstein DU. Health insurance and mortality in US adults. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(12):2289–2295. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.157685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaiser Family Foundation and the Health Research and Education Trust. Employer health benefits: 2011 annual survey. 2011 Available from: http://ehbs.kff.org/pdf/2011/8225.pdf.

- 12.Vistnes JP, Zawacki A, Simon K, Taylor A. Declines in employer-sponsored insurance coverage between 2000 and 2008: Examining the components of coverage by firm size. Health Services Research. 2012;47(3 Pt 1):919–938. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01368.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shen YC, Long SK. What’s driving the downward trend in employer-sponsored health insurance? Health Services Research. 2006;41(6):2074–2096. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00590.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reschovsky JD, Strunk BC, Ginsburg P. Why employer-sponsored insurance coverage changed, 1997–2003. Health Affairs. 2006;25(3):774–782. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lavarreda SA, Brown ER, Cabezas L, Roby DH. Number of uninsured jumped to more than eight million from 2007 to 2009. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medicaid.gov. Children’s health insurance program. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2012. Available from: http://www.medicaid.gov/Medicaid-CHIP-Program-Information/By-Topics/Childrens-Health-Insurance-Program-CHIP/Childrens-Health-Insurance-Program-CHIP.html (cited 2012 March 6) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi M, Sommers BD, McWilliams JM. Children’s health insurance and access to care during and after the CHIP expansion period. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22(2):576–589. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act of 2009 (CHIPRA) Washington, DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2009. Children’s. Available from: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/7863.pdf (cited 2011 January 14) [Google Scholar]

- 19.111th Congress. Compilation of Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act 2010. 2010 Available from: http://docs.house.gov/energycommerce/ppacacon.pdf (cited 2011 December 16)

- 20.DeVoe JE, Tillotson CJ, Wallace LS. Children’s receipt of health care services and family health insurance patterns. Annals of Family Medicine. 2009;7(5):406–413. doi: 10.1370/afm.1040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeVoe JE, Ray M, Graham A. Public health insurance in Oregon: Underenrollment of eligible children and parent confusion about children’s enrollment status. American Journal of Public Health. 2011;101(5):891–898. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.196345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davidoff A, Dubay L, Kenney G, Yemane A. The effect of parents’ insurance coverage on access to care for low-income children. Inquiry. 2003;40(3):254–268. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_40.3.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fronstin P. Sources of health insurance and characteristics of the uninsured: Analysis of the March 2011 current population survey. EBRI Issue Brief. 2011;362:1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fronstin P. Sources of health insurance and characteristics of the uninsured: Analysis of the March 2008 current population survey. EBRI Issue Brief. 2008;321:1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen RA, Makuc DM, Bernstein AB, Bilheimer LT, Powell-Griner E. Health insurance coverage trends, 1959–2007: Estimates from the national health interview survey. National Health Statistics Reports. 2009;17:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simpson L, Owens PL, Zodet MW, Chevarley FM, Dougherty D, Elixhauser A, et al. Health care for children and youth in the United States: Annual report on patterns of coverage, utilization, quality, and expenditures by income. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2005;5(1):6–44. doi: 10.1367/A04-119R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larson K, Halfon N. Family income gradients in the health and health care access of US children. Maternal and Child Health. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0477-y. Epub June 5, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen J, Monheit A, Beauregard K, et al. The medical expenditure panel survey: A national health information resource. Inquiry. 1996–1997 Winter;33(4):373–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Medical expenditure panel survey. Silver Springs, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2004. Available from: http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/ (cited 2007 August 20) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weinick RM, Zuvekas SH, Drilea SK. Access to health care: Source and barriers, 1996; MEPS research findings no. 3. AHCPR Pub. No. 98-0001. Rockville, MD: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zuvekas SM, Weinick RM. Changes in access to care, 1977–1996: The role of health insurance. Health Services Research. 1999;34(1):271–279. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J, Monheit A, Beauregard K, et al. The medical expenditure panel survey: A national health information resource. Inquiry. 1996 Winter;:373–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen S. Sample design of the 1996 medical expenditure panel survey household component. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 1997. MEPS methodology report no. 2, Pub. No. 97-0027. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS HC-036: 1996–2006 pooled estimation file. 2008 Available from: http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h36/h36u06doc.shtml (cited 2009 February 20)

- 35.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Household component linking MEPS data. 2009 Available from: http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/workbook/WB-Linking.pdf (cited 2009 March 1)

- 36.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. MEPS HC-089: 2004 full year consolidated data file 2004. 2004 Available from: http://www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_stats/download_data/pufs/h89/h89doc.pdf (cited 2008 January 10)

- 37.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Moving ahead amid fiscal challenges: A look at medicaid spending, coverage and policy trends. Results from a 50-state medicaid budget survey for state fiscal years 2011 and 2012. Washington, DC: The Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, Brogan DJ. Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2010;171(5):618–623. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hudson JL, Selden TM. Children’s eligibility and coverage: Recent trends and a look ahead. Health Affairs. 2007;26(5):w618–w629. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.w618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dubay L, Kenney G. The impact of CHIP on children’s insurance coverage: An analysis using the National Survey of America’s Families. Health Services Research. 2009;44(6):2040–2059. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2009.01040.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dubay L, Guyer J, Mann C, Odeh M. Medicaid at the ten-year anniversary of SCHIP: Looking back and moving forward. Health Affairs. 2007;26(2):370–381. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.2.370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Children’s health—why insurance matters: Kaiser family foundation. 2002 Available from: http://www.kff.org/uninsured/4055-index.cfm (cited 2007 August 20)

- 43.Stevens GD, Seid M, Halfon N. Enrolling vulnerable, uninsured but eligible children in public health insurance: Association with health status and primary care access. Pediatrics. 2006;117(4):e751–e759. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hadley J. Sicker and poorer: The consequences of being uninsured. Medical Care Research and Review. 2003;60(2 Suppl):3S–75S. doi: 10.1177/1077558703254101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamauchi M, Carlson MJ, Wright BJ, Angier H, Devoe JE. Does health insurance continuity among low-income adults impact their children’s insurance coverage? Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s10995-012-0968-0. Epub Feb 24, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The health care law & you: What’s changing when. 2012 Available from: http://www.healthcare.gov/law/timeline/index.html (cited 2012 February 2)

- 47.Shoen C, Doty MM, Robertson RH, Collins SR. Affordable care act reforms could reduce the number of uninsured US adults by 70 percent. Health Affairs. 2011;30(9):1762–1771. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kenney G, Buettgens M, Guyer J, Heberlein M. Improving coverage for children under health reform will require maintaining current eligibility standards for medicaid and CHIP. Health Affairs. 2011;30(12):2371–2381. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Implementing the ACA’s medicaid-related health reform provisions after the supreme court’s decision. 2012 Aug [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kenney G, Dubay L, Zuckerman S, Huntress M. Making the medicaid expansion an ACA option: How many low-income Americans could remain uninsured? Washtington, DC: The Urban Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 51.McDonough JE. The Road Ahead for the Affordable Care Act. New England Journal of Medicine. 2012;367(3):199–201. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1206845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]