Abstract

Patient: Male, 61

Final Diagnosis: Benazepril induced agranulocytosis

Symptoms: Sepsis

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: None

Specialty: Critical Care Medicine

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors are widely used drugs, and in appropriately selected patients, serious side effects are infrequent. Commonly seen side effects include cough, rash, hyperkalemia, renal dysfunction, and angioedema. Historically, dose-related agranulocytosis has been associated with captopril. Benazepril, a relatively more potent angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, is rarely associated with agranulocytosis.

Case Report:

Here, we report a case of drug-induced agranulocytosis due to benazepril, with complete recovery of white blood cell count upon discontinuation of the drug. All tests for other causes of agranulocytosis were unremarkable. This report highlights a serious and rare side effect associated with benazepril.

Conclusions:

Benazepril is a commonly employed anti-hypertensive medication, and we report an unusual condition associated with this medication in order to increase vigilance among caregivers. In such cases, prompt recognition and discontinuation of the causative drug can make the difference between a recovery and a fatal outcome associated with drug-induced agranulocytosis.

MeSH Keywords: Abnormalities, Drug-Induced; Agranulocytosis; Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme Inhibitors

Background

Neutropenia is usually defined as an absolute neutrophil count (ANC) below 1,500 cells/μL (<1.5×109/L). Agranulocytosis, a life-threatening condition also known as granulocytopenia, is defined as severe neutropenia (i.e., ANC <500 cells/μL). This severe decrease in infection-fighting cells leaves the patient at high risk for serious infections. The majority of cases are acquired as a secondary complication to the administration of certain drugs [1]. Although this complication is associated with an increasing number of drugs, the current literature shows a stable incidence of drug-induced agranulocytosis (DIAG). However, an accurate estimation of incidence is difficult to quantify because the condition is likely underreported [2]. The detailed pathological mechanism of DIAG is poorly understood and a causal relationship between the condition and a drug can be difficult to elicit. Most of the literature on DIAG is based on reported cases rather than epidemiological studies, and there is a need for increased awareness of drugs that can cause neutropenia in order to avoid fatal complications.

There are many drugs listed in the etiology of DIAG, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs). ACEIs are considered first-line medications for congestive heart failure and hypertension, especially in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease. ACEIs have a good safety profile, are rarely associated with adverse events, and are generally not life-threating [3]. Despite these encouraging statistics, captopril has been reported to cause agranulocytosis. Here, we present a rare case of agranulocytosis following treatment with benazepril. There are very few suspected cases of agranulocytosis submitted to the WHO newsletter; to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of benazepril-induced agranulocytosis reported in the curated literature on the PubMed database.

Case Report

A 61-year-old, Hispanic male was admitted to the emergency department with complaints of throat pain and difficulty swallowing which had lasted one week. The patient denied any contact with individuals known to be sick. There was no history of recent travel, weight loss, or night sweats. The only comorbid condition was hypertension. The patient denied any history of smoking or recreational drug abuse. In the emergency department, vital signs were within normal limits, except for a temperature of 102°F (38.8°C). Physical examination revealed good bilateral equal air entry with no added rhonchi or wheezing. Cardiovascular and neurological examinations revealed no abnormalities. The abdomen was soft and non-tender, without palpable visceromegaly.

Complete blood count showed white blood cell count of 0.5 K/μL with absolute neutrophilic count of zero, normal hemoglobin level, mildly decreased hematocrit of 39%, and normal platelet count. The patient was diagnosed as having febrile neutropenia, and therefore, admitted to the hospital for additional investigation and management.

Initially, the patient was started on broad-spectrum antibiotics for pharyngitis and suspected pharyngeal abscess. Peripheral smear, comprehensive metabolic panel, and hemoglobin electrophoresis were within normal limits. Results of a malaria smear were negative. T and B cell assay was normal. HTLV I and II antibody assays were negative. Heterophilic antibodies were not detected, and tests for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV-VCA) IgM, HIV, RPR, and ANA were negative. Serum protein electrophoresis showed only a decrease in albumin, but all other serum proteins were within normal concentrations. Neutrophil antibodies were not detected. The patient’s ferritin level was elevated to 627.8 ng/mL; however, vitamins, folate, and LDH levels were normal. A test for hepatitis A total antibody was positive. Hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B surface antibody, and hepatitis C antibody were negative. Blood culture, throat culture, blood fungal culture, acid-fast bacillus blood culture, and urine culture were all negative. A urine toxicology screen was also negative.

A chest radiograph, abdomen ultrasound, and computed tomography of the head and neck were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid was sent for several tests, including a venereal disease research laboratory test, assays for bacterial antigens, viral culture, CMV PCR, Gram stain, acid-fast bacillus culture, aerobic culture, and fungal cultures. All these tests came back negative. Cell counts and differentials, protein levels, and glucose level were within normal limits.

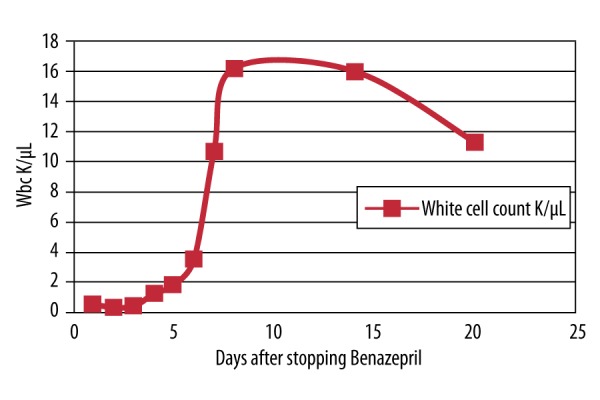

The patient’s home medications included amlodipine and benazepril. Benazepril was added for treatment of the patient’s anti-hypertension approximately two months prior to the onset of symptoms. Benazepril, thought to be the offending agent causing agranulocytosis, was discontinued. This resulted in fast recovery of the white blood cell count. The patient remained afebrile for one week and was discharged with a diagnosis of benazepril-induced agranulocytosis. The patient was followed for two additional weeks in the clinic, and repeated blood tests showed that the white blood cell count was 11.3 K/μL with 83% neutrophils after 21 days. The change in white blood cell count over time is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

White blood cell count after treatment with benazepril.

Amlodipine has been reported to cause neutropenia only rarely, and a history of the recent addition of benazepril was more suggestive of it being the cause. In addition, the patient recovered completely upon discontinuation of benazepril, and negative test results for other possible secondary causes of agranulocytosis helped to confirm the diagnosis of DIAG secondary to benazepril.

Discussion

Neutropenia is defined as an ANC <1,500 cells/μL. The term “agranulocytosis,” first introduced in 1922 by Schultz, means a lack of granulocytes, and is used for severe neutropenia (ANC <500 cells/μL) [4]. Agranulocytosis is a rare and serious condition, and medications account for nearly two-thirds of cases [5]. Despite the emergence of new drugs, incidence of DIAG has remained stable over the last two decades and varies between 3.4 to 5.3 cases per million population per year in Europe and 2.4 to 15.4 per million population per year in the USA [6].

DIAG manifests as an idiosyncratic reaction and is associated with high morbidity. Pathophysiological mechanisms of DIAG are poorly understood and highly speculative. In addition, there is no gold standard test for the diagnosis of DIAG, which warrants the need for increased awareness and high vigilance among clinicians to report these drug reactions [7].

Emmanuel et al. reviewed the drugs that have been implicated in the occurrence of agranulocytosis. In addition to these medications, Emmanuel et al. identified old age, septicemia or shock, and metabolic disorders as poor prognostic factors for agranulocytosis [8]. Clinical manifestations have been historically described as edema, necrosis, and pharyngitis, followed by coma and death within days. Oral ulcers, septicemia, septic shock, pneumonia, sore throat, acute tonsillitis, and skin and deep seated infections are other reported complications of DIAG [6,8].

DIAG can occur via immune-mediated destruction of circulating neutrophils by antibodies or by direct toxic effects of a drug on marrow granulocytic precursors; both mechanisms are mediated by reactive metabolites [9]. Alexander et al. recently reviewed the mechanism of DIAG, concluding that it is an idiosyncratic response triggered by reactive metabolites of the causative drug. The ability of a drug to be converted to reactive metabolites was thought to be a useful marker to predict the risk of DIAG; however, the research to support this hypothesis is lacking [10]. Among non-chemotherapy drugs, antibiotics are the most common medications associated with DIAG [11]. Some of the medications that can cause DIAG have their own particular risk factors, such as HLA-B27, HLA-B35, and HLA-B38 in patients with clozapine-associated agranulocytosis [12].

Among ACEIs, captopril is well known to cause agranulocytosis, especially in patients with autoimmune disease or renal failure [13,14]. Enalapril was also assumed to be the cause of agranulocytosis in a patient who developed agranulocytosis while taking verapamil and enalapril. Both drugs were discontinued upon diagnosis of agranulocytosis, resulting in rapid restoration of white blood cells [15]. Benazepril acts as an ACEI by decreasing the synthesis of angiotensin II. It is rapidly absorbed and more potent in vitro than other inhibitors [16]. While taking benazepril, eight patients have been reported to have developed agranulocytosis, according to a pharmaceutical newsletter. Definite improvement was reported following the cessation of benazepril treatment in two cases only, and it was concluded that these reports are inconclusive and alone do not justify a warning [17]. We extensively searched the literature and could not find any reports describing benazepril-associated agranulocytosis. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of benazepril-associated agranulocytosis reported in the curated PubMed database.

The diagnosis of DIAG requires a detailed medication history and high index of suspicion for possible offending medications. Diagnostic criteria for DIAG include: a neutrophil count <500 cells/mm3, hemoglobin >10 g/dL, a platelet count >100,000 cells/mm3, history of drug exposure, and no previous indication of a secondary cause of agranulocytosis [18].

The other major causes of neutropenia in adults include benign ethnic neutropenia, nutritional deficiencies, collagen vascular disorders, and hematologic disorders such as myelodysplasia [19]. In our patient, the testing designed to elucidate secondary causes of agranulocytosis was unremarkable. The patient did not have any history of neutropenia in the past, and there was no remission after benazepril was stopped, a result that contraindicates a diagnosis of cyclic neutropenia.

Certain bacterial infections, such as typhoid fever, shigellosis, brucellosis, and tuberculosis are often associated with neutropenia. In addition, some viruses, including human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis A, cytomegaloviruses, and Epstein-Barr virus can cause neutropenia. About half of patients with HIV have neutropenia, usually due to autoimmune destruction of neutrophils [20]. In our patient, complete diagnostic testing did not reveal any evidence of an infection.

Conclusions

For DIAG, most data come from case reports. Because ACEI are commonly employed drugs, we report this case to increase awareness among prescribers about this rare but potentially lethal side effect of benazepril. Previously described cases of ACEI-induced agranulocytosis are mainly reported with captopril and in the context of renal disorder or rheumatologic conditions. Our case is unique because benazepril was found to be the sole cause of agranulocytosis for this patient.

Successful recovery of white blood cell count upon discontinuation of the medication without further recurrence highlights the importance of prompt recognition to avoid untoward effects.

Abbreviations:

- ACEIs

angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

- DIAG

drug-induced agranulocytosis

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- HTLV

human T-lymphotropic virus

- RPR

rapid plasma regain

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- WHO

World Health Organization

Footnotes

Statement

No funding was provided for the production of this case report.

References:

- 1.Ibáñez L, Vidal X, Ballarín E, Laporte JR. Population-based drug-induced agranulocytosis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(8):869–74. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.8.869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van der Klauw MM, Goudsmit R, Halie MR, et al. A population-based case-cohort study of drug-associated agranulocytosis. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(4):369–74. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.4.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parish RC, Miller LJ. Adverse effects of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. An update. Drug Saf. 1992;7(1):14–31. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199207010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersohn F, Konzen C, Garbe E. Systematic review: Agranulocytosis induced by nonchemotherapy drugs. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(9):657–65. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-9-200705010-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Jurgelon JM, et al. Drugs in the aetiology of agranulocytosis and aplastic anaemia. Eur J Haematol Suppl. 1996;60:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1996.tb01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrès E, Zimmer J, Affenberger S, et al. Idiosyncratic drug-induced agranulocytosis: Update of an old disorder. Eur J Intern Med. 2006;17(8):529–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Navarro-Martinez R, Chover-Sierra E, Cauli O. Non-chemotherapy drug-induced agranulocytosis in a tertiary hospital. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2016;35(3):244–50. doi: 10.1177/0960327115580603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andrès E, Zimmer J, Mecili M, et al. Clinical presentation and management of drug-induced agranulocytosis. Expert Rev Hematol. 2011;4(2):143–51. doi: 10.1586/ehm.11.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tesfa D, Keisu M, Palmblad J. Idiosyncratic drug-induced agranulocytosis: Possible mechanisms and management. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(7):428–34. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston A, Uetrecht J. Current understanding of the mechanisms of idiosyncratic drug-induced agranulocytosis. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015;11(2):243–57. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2015.985649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Andrès E, Maloisel F, Kurtz JE, et al. Modern management of non-chemotherapy drug-induced agranulocytosis: A monocentric cohort study of 90 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Intern Med. 2002;13(5):324–28. doi: 10.1016/s0953-6205(02)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dettling M, Cascorbi I, Roots I, Mueller-Oerlinghausen B. Genetic determinants of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: Recent results of HLA subtyping in a non-jewish caucasian sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):93–94. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pillans PI, Koopowitz A. Captopril-associated agranulocytosis. A report of 3 cases. S Afr Med J. 1991;79(7):399–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Staessen J, Fagard R, Lijnen P, Amery A. Captopril and agranulocytosis. Lancet. 1980;1(8174):926–27. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)90853-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elis A, Lishner M, Lang R, Ravid M. Agranulocytosis associated with enalapril. DICP. 1991;25(5):461–62. doi: 10.1177/106002809102500502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hilal-Dandan R. Renin and Angiotensin. In: Brunton LL, Chabner BA, Knollmann BC, editors. Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 12e. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization Benazepril and agranulocytosis: A possible rare adverse reaction involving ACE inhibitors as a class. WHO Pharmaceuticals Newsletter. 2003;2:9. Available from: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4945e/3.1.html#Js4945e.3.1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Munshi HG, Montgomery RB. Severe neutropenia: a diagnostic approach. West J Med. 2000;172(4):248–52. doi: 10.1136/ewjm.172.4.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dale DC, Guerry D, IV, Wewerka JR, et al. Chronic neutropenia. Medicine (Baltimore) 1979;58(2):128–44. doi: 10.1097/00005792-197903000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Murphy MF, Metcalfe P, Waters AH, et al. Incidence and mechanism of neutropenia and thrombocytopenia in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Br J Haematol. 1987;66(3):337–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb06920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]