Abstract

Objective: To determine the exact role of sodium channel proteins in migration, invasion and metastasis and understand the possible anti-invasion and anti-metastatic activity of repurposed drugs with voltage gated sodium channel blocking properties.

Material and methods: A review of the published medical literature was performed searching for pharmaceuticals used in daily practice, with inhibitory activity on voltage gated sodium channels. For every drug found, the literature was reviewed in order to define if it may act against cancer cells as an anti-invasion and anti-metastatic agent and if it was tested with this purpose in the experimental and clinical settings.

Results: The following pharmaceuticals that fulfill the above mentioned effects, were found: phenytoin, carbamazepine, valproate, lamotrigine, ranolazine, resveratrol, ropivacaine, lidocaine, mexiletine, flunarizine, and riluzole. Each of them are independently described and analyzed.

Conclusions: The above mentioned pharmaceuticals have shown anti-metastatic and anti-invasion activity and many of them deserve to be tested in well-planned clinical trials as adjunct therapies for solid tumors and as anti-metastatic agents. Antiepileptic drugs like phenytoin, carbamazepine and valproate and the vasodilator flunarizine emerged as particularly useful for anti-metastatic purposes.

Keywords: Voltage-gated sodium channels, cancer, phenytoin, flunarizine, repurposed drugs, metastasis

Introduction

The capacity to metastasize is one of the hallmarks of cancer 1 and usually death due to cancer is not caused by the primary tumor but rather by the metastatic spread 2. The lack of an effective therapy in prevention of metastasis results in a high mortality rate in oncology. So it seems reasonable that if the risk of metastasis can be reduced, the outlook of cancer patients may significantly improve survival and quality of life. Solving the metastasis problem is solving the cancer problem 3.

Many natural products, like genistein 4, resveratrol 5 and curcumin 6, 7 have shown interesting anti-metastasis activity. The same effect has been observed with older pharmaceuticals like aspirin 8, not-as-old pharmaceuticals such as celecoxib 6, 9; new pharmaceuticals like ticagrelor 10, as well as with more sophisticated molecules like dasatinib and ponatinib 6 or ultrasophisticated drugs, like polymeric plerixafor 11.

Many other compounds have also been identified as possessing anti-metastatic effects, including increases in NO 12, cimetidine, doxycycline, heparin and low molecular heparins, and metapristone 13.

High creativity has been employed in the search for anti-metastatic compounds. For example, Ardiani et al. developed a vaccine-based immunotherapy to enhance CD4 and CD8 T lymphocyte activity against Twist 14. Twist is a transcription factor involved in invasion and metastasis.

Many known pharmaceuticals that are, or were, in use for other purposes than cancer treatment are demonstrating anti-metastatic activity. This is the case for thiobendazole, which is an antifungal, anti-parasitic drug that has been used in medical practice for over 40 years, but which also shows anti-migratory and apoptosis-inducing activity 15. The introduction of Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved products which are used for a purpose different for which it was originally approved is called repurposing of a drug.

Many new drugs are being introduced in the area of anti-metastatic activity. One such example, zoledronic acid 16 is a biphosphonate that decreases bone metastasis. Denosumab 17 is another example. It is a monoclonal antibody directed against the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa B ligand (RANKL) that diminishes the number of circulating cancer cells and prevents bone metastasis. It is in Phase II clinical trials and has the advantage of subcutaneous administration, while zoledronic acid requires intravenous route (for further information on these compounds, see clinical trials NCT01952054, NCT01951586, NCT02129699) 18.

Metastasis is a multi-step development. The different steps in the metastatic cascade can be targeted with a combination of drugs against each step. Migration and invasion are necessary steps for the metastatic cascade. There is no metastasis without prior migration of malignant cells, so that if migration and invasion are blocked, metastasis should not occur.

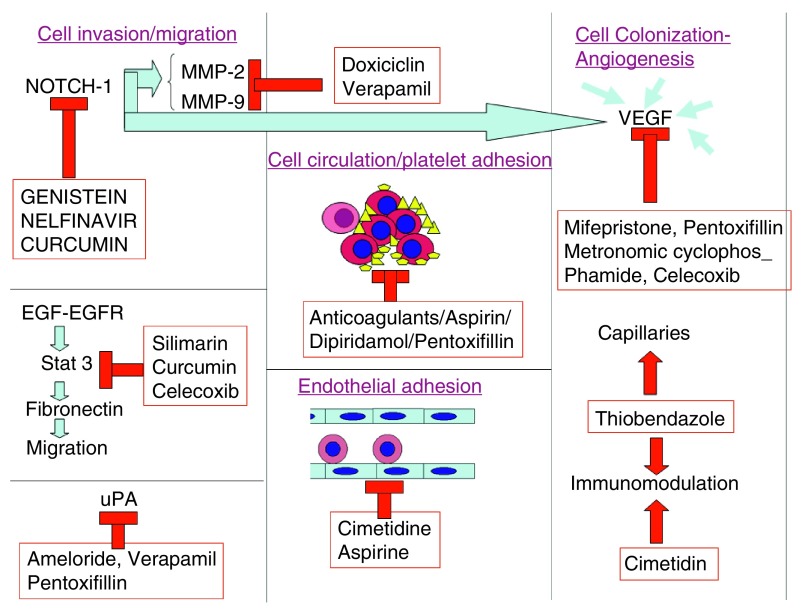

Invasion is the first step in metastasis, and in a very simplified view, it can be divided into three stages (Shown schematically in Figure 1):

Figure 1. Repurposed drugs acting at different levels of the metastatic cascade.

(uPA: urinary plasminogen activator).

-

1.

Translocation of cells across extracellular matrix barriers

-

2.

Degradation of matrix proteins by specific proteases

-

3.

Cell migration

Voltage-gated sodium channels

Neurons and muscle cells (and excitable tissues in general) express voltage-gated sodium channel (VGSC) proteins; tumor cells may also express these proteins. VGSCs are important players in migration and invasion as it will be described in this manuscript.

Sodium channels were first described by Hodgkin and Huxley in 1952 and knowledge about structure and physiology of VGSCs are mainly the result of seminal investigations developed by William Catterall 19.

Sodium channels are glycosylated transmembrane proteins that form passages in the cell membrane for the penetration of sodium into the intracellular space according to their electrical gradients. Voltage-gated sodium channels (also known as VGSCs or ‘NaV’ channels) refers to the mechanism that triggers these proteins to allow sodium movement across the membrane.

There are nine known VGSCs (NaV1.1 to Nav1.9) that are members of the superfamily of VGCSs. NaV1.1, 1.2, 1.3 and 1.6 are found in the central nervous system. NaV1.4 is found in muscle and NaV1.5 in cardiac muscle 20.

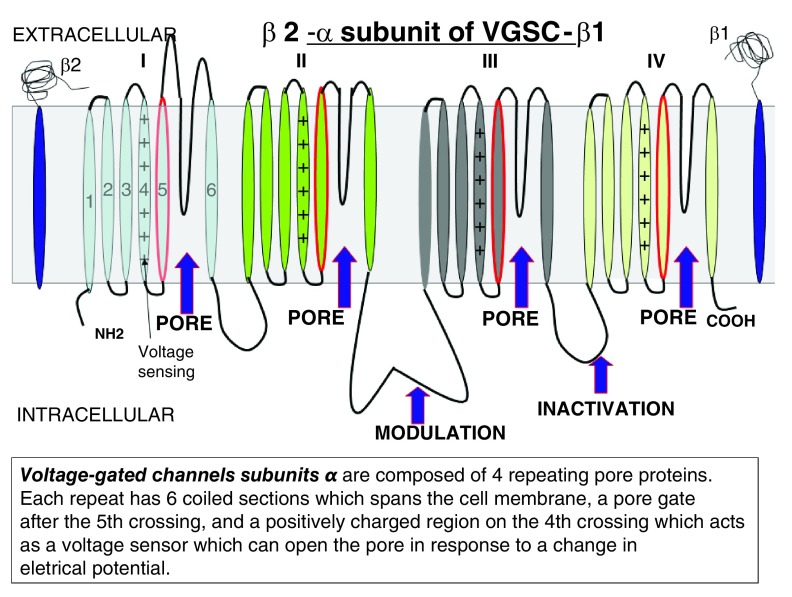

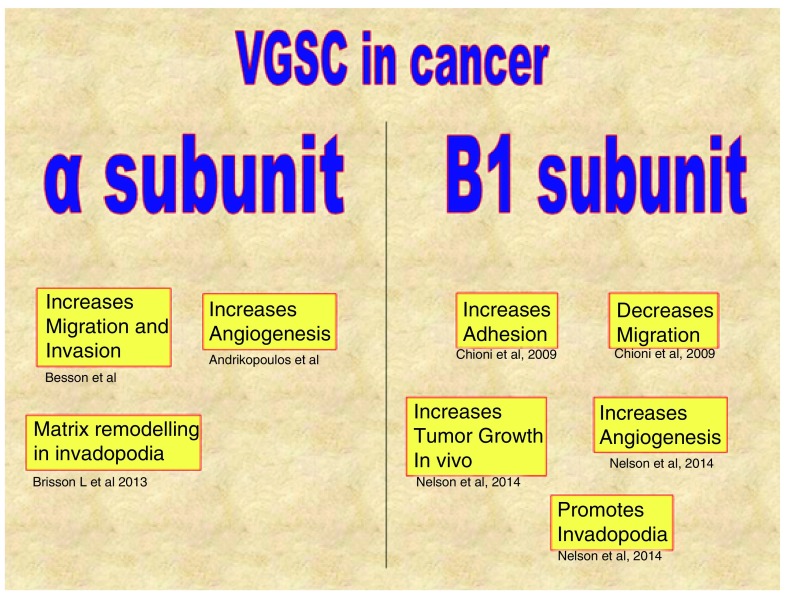

VGSC is formed by a large subunit (α) and other smaller subunits (β). The α subunit is the core of the channel and is fully functional by itself, even without the presence of β subunits 19– 21.

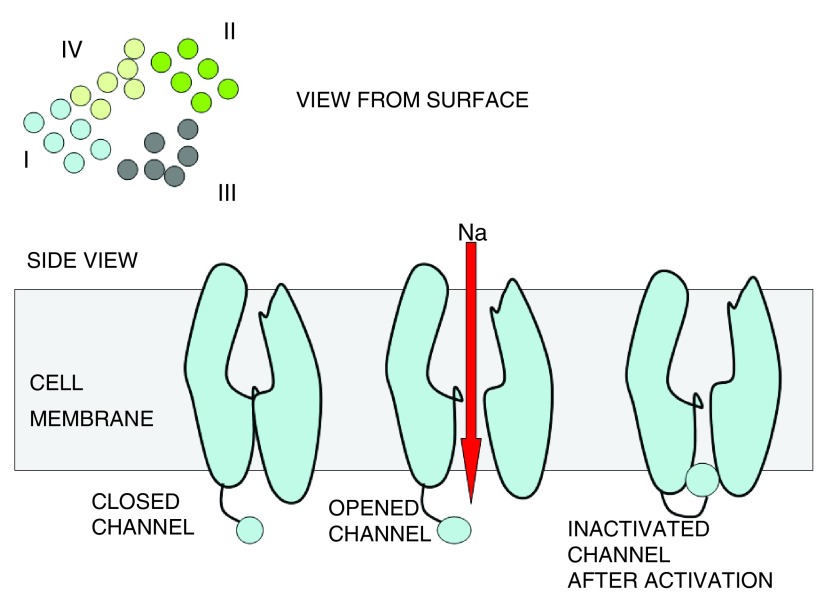

When a cell expresses VGSC α subunits, this means that it is capable of conducting sodium into the cell. The structure of VGSC can be seen in Figure 2 and Figure 3. VGSCs modulate the exchange of Na+ across the cell membrane and the inflow of this electrolyte spikes the action potential in excitable tissues 22.

Figure 2. An idealized drawing of α and β units of VGSCs.

Figure 3. Surface and side view of VGSC.

It is well known that expression of VGSCs appears in cancer cells where it is not expressed in their normal counterparts, and plays a significant role in disease progression. Table 1 shows examples of the cancer tissues in which dysregulated expression of VGSCs were identified and the role they play.

Table 1. VGSC functional over-expression in different cancer tissues.

| Cancer | Reference | Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Human breast cancer | Fraser, 2005 23 | VGSC (neonatal isoform of NaV1.5) was significantly upregulated in metastatic cells.

VGSC activity increased endocytosis, migration and invasion |

| Non small-cell lung

cáncer (NSCLC) |

Roger, 2007 24 | Strongly metastatic cell lines have functional VGSCs while normal cells do not have it.

Inhibition of channels with tetrodotoxin (TTX) reduced invasivenes by 50%. |

| Small cell lung cáncer

(SCLC) |

Blandino, 1995 25 | VGSCs are over-expressed in SCLC. |

| Cervical cancer cells | Diaz, 2007 26 | Na

v1.2, Na

v1.4, Na

v1.6, and Na

v1.7 transcripts were detected in cervical cancer cell

specimens. |

| Prostate cancer | Bennett, 2004 27 | VGSC expression increases with invasion capacity that can be blocked with TTX.

Increased VGSC expression is enough to increase invasive phenotype. |

| Metastatic ovarian

cancer cells |

Gao, 2010 28 | Highly metastatic ovarian cells showed significantly elevated expression of Nav1.2,

Nav1.4, Nav1.5 and Nav1.7. TTX reduced migration and invasion around 50%. |

| Human colon cancer

cells |

House, 2010 29 | SCN5A, the gene coding for α sububit of VGSC is a regulator of the invasive phenotype. |

| T lymphocytes (Jurkat

cells) |

Fraser, 2004 30 | Jurkat cells express VGSC and this protein has an important role in invasiveness of these

cells. |

| Pancreatic cancer

cells |

Sato K, 1994 31 | MIA-PaCa-2 and CAV cells were tested

in vitro and

in vivo with phenytoin (PHEN). Both

cell lines showed growth inhibition in a dose dependable manner. This might be due to VGSC overexpression according to our criteria (the authors think that this was due to calcium channel blocking). |

| Mesothelial

neoplastic cells |

Fulgenzi, 2006 32 | Express VGSCs, particularly NaV1.2, and NaV1.6, and NaV1.7. TTX decreased cell

motility and migration. |

Targeting these channels may represent a legitimate way of reducing or blocking the metastatic process.

The role of sodium channel in invasion, metastasis and carcinogenesis is insufficiently known.

Sodium channel proteins and cancer

In 1995, Grimes et al. 33 investigated the differential electrophysiological characteristics of VGSCs in two different rodent prostate cancer cell lines: the Mat-Ly-Lu cell line, which is a highly metastatic line (more than 90% of metastasis to lung and lymph nodes under experimental conditions) and the AT-2 cell line with a much lower metastatic potential (less than 10% chance of developing metastasis in experimental conditions). They found fundamental differences in electrophysiological features between these two cell lines which displayed a direct relationship with in vitro invasiveness. Sodium inward currents were detected only in the Mat-Ly-Lu cell line and inhibition of VGSC protein with Tetrodotoxin (TTX; a powerful inhibitor of VGSCs) significantly reduced the capacity for invasion (mean reduction 33%). On the other hand, TTX showed no effect on invasion of AT-2 cell lines. The TTX-induced reduction of invasion showed a direct correlation with the amount of cells expressing VGSC in the culture.

No fundamental differences in the potassium channels were found between the two cell lines, except for a lower density of potassium channels in the Mat-Ly-Lu cell line. The authors concluded that ion channels may be involved in malignant cell behavior and that VGSCs could play a role in the metastatic process.

In 1997, Laniado et al. 34 investigated the presence of VGSC in human prostate cell lines. As in the Grimes research they used two different cell lines: one with a low metastatic potential: the LN-Cap cell line which is androgen dependent and expresses prostate-specific antigen, and the PC-3 line which is more malignant, does not express prostate-specific antigen and exhibits a high rate of metastatic potential.

As in the work by Grimes et al., they found that PC-3, the more malignant cell line, expressed VGSC protein and that inhibition of this channel protein with TTX reduced invasion in a significant way. LN-Cap cells did not express VGSC.

One of the conclusions reached by the authors was that cancer cells expressing functional VGSC had a selective advantage regarding migration and distant metastasis. In the case of both humans and rodents, not all cells in the highly malignant cell cultures showed the presence of the VGSC protein. For example, in PC-3 cell culture only 10% of cells expressed a functional VGSC protein. This is the reason why the authors consider these cells as a clonal evolution that gives pro-tumor and pro-invasive advantages.

The correlation between VGSC protein expression and invasiveness in human and rat prostate cancer cells was confirmed by Smith et al. 35 by comparing seven lines of rat prostate carcinoma cells with different metastatic ability, and nine human prostate carcinoma cell lines. In general, invading capacity of the basement membrane and metastatic ability showed a positive correlation with the percentage of cells expressing VGSC. But this positive correlation between percentage of cells expressing VGSCs and the percentage of cells being invasive occurred only up to 27% of the cells being invasive in the rat series and up to 12% of cells being invasive in the human series. Authors suggested that these discrepancies may be due to the necessity of other factors for invasive capability besides VGSC presence; i.e. this protein may represent a prerequisite for the invasive phenotype but other requirements must also be achieved for a full-blown invasive phenotype. Fraser et al. 36 determined the key role played by VGSCs in prostate cancer cells in invasion and motility and showed that TTX and phenytoin (PHEN) that are known VGSC blockers, decreased motility and invasiveness while channel openers increased motility. However, the increased invasion capacity in VGSC-expressing cancer cells is not limited to prostate cancers. The same features were found in breast cancer cell lines MCF-7 (estrogen receptor positive), MDA-MB-231 and MDA-MB-468 (both estrogen receptor negative).

Baciotglu et al. 38 when experimenting on a rat model of induced breast cancer showed the importance of inhibiting VGSCs in order to inhibit antioxidant response. They observed a survival improvement in rats treated with a VGSC blocker.

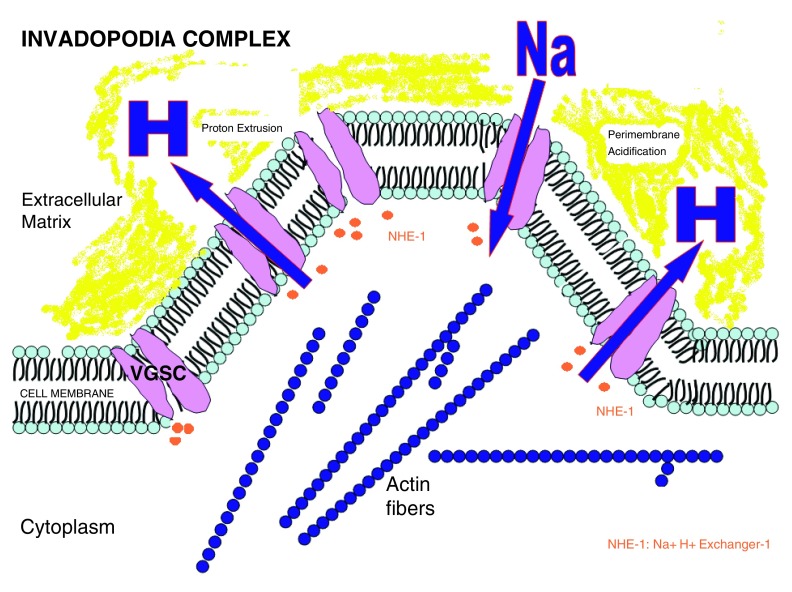

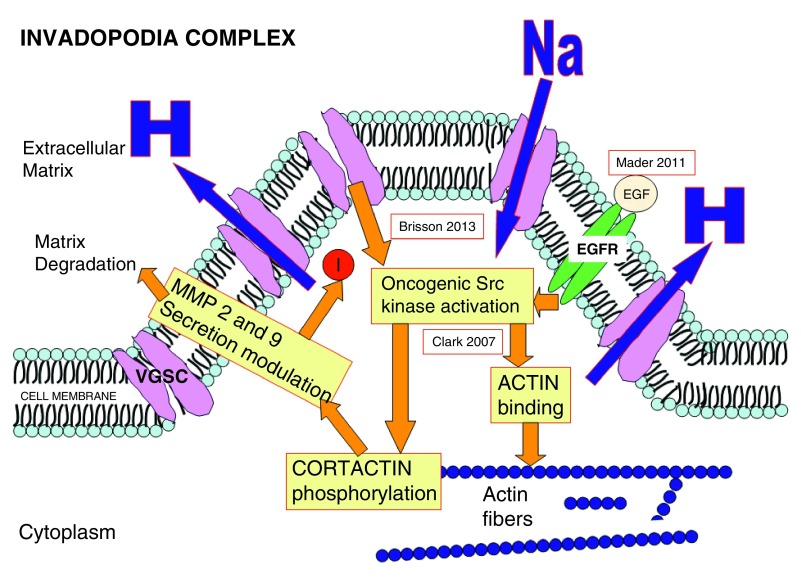

An important location of VGSCs in cancer cells is in a cellular region directly involved in migration and invasion: the invadopodia. Invadopodias are protrusions of the plasma membrane, rich in actin that are strongly related to degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM). Figure 4 and Figure 5 summarize how invadopodia works and the relation between VGSC and invadopodia.

Figure 4. Proton extrusion through VGSC and NHE-1 (sodium hydrogen exchanger-1) produces acidification of extracellular matrix surrounding the cellular membrane (yellow area in the figure).

(Brisson 2013 39; Gillet 2009 40). Acidification activates cathepsine degradation of the extracellular matrix.

Figure 5. VGSCs.

The second mechanism of action is through activation of Src which increases MMP-2 and MMP-9 secretion and activity through phosphorylation of Cortactin. It is postulated that there is a feedback loop starting with MMPs products which induces the development of new invadopodia (Red circle around I). (This figure has been constructed based on references Gillet 2009 40, Brisson 2013 133, Clark 2007 42 and Mader 2011 41).

According to Brisson et al. 39, NaV 1.5 Na+ channels regulate the NHE-1 exchanger protein that increases proton extrusion with extracellular matrix acidification that promotes invasion and migration through activity of cystein cathepsines and degradation of extracellular matrix 40.

A second mechanism of invasion promotion was described by Mader et al. 41 through the EGFR-Scr-cortactin pathway. Src is activated by VGSCs and Src phosphorylates cortactin. Cortactin is involved in MMP-9 and MMP-2 upregulation and secretion as can be seen in Figure 5. These events lead to matrix degradation, an integral step in cancer cell invasion 42.

There are nine different VGSC α subunits and four different β subunits. The expression of these subunits may vary in the different tumor cells 21. For example, NaV 1.5 is overexpressed in astrocytoma, breast and colon cancer. NaV 1.7 is found in breast, prostate and non small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and NaV 1.6 in cervical and prostate cancer. This suggests that the α subunits seem to be tissue specific.

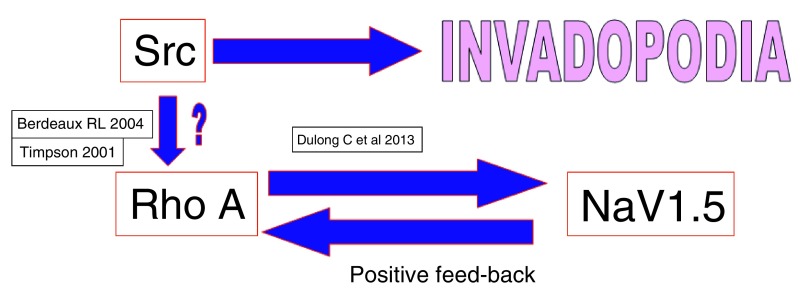

The main players in the invadopodia complex, besides the VGSCs are Src kinase, cortactin and Rho-A GTPase. The exact relation between these players is not fully known and needs further research. (For further reading on invadopodia and cortactin, see references 43, 44).

One possible relation between invadopodia-Src-VGSCs is described in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Tarone et al. 46 in 1985 reported the relation between the oncogenic Src and promotion of invadopodia.

Berdeaux et al. 47 reported that the small molecule GTPase Rho A activity is under control of oncogenic Src and localizes in the invadopodia complex and Durlong et al. 48 (2013) showed that Rho-A regulates the expression and activity of NaV1.5 and found a positive feedback between NaV1.5 and Rho A in breast cancer cells. According to Timpson et al. 49, cooperation between mutant p53 and oncogenic Ras activates Rho-A.

Figure 7. Activities of alpha and beta-1 subunits of VGSCs in cancer 131– 133.

Onganer and Djamgoz 45 proposed the hypothesis that VGSC upregulation enhances the metastatic phenotype by enhancing endocytic membrane activity in SCLC.

Andrikopoulus et al. 50 have demonstrated that VGSCs have pro-angiogenic functions by significantly increasing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling in endothelial cells. Endothelial cells express NaV1.5 and NaV1.7. TTX blocks, and NaV1.5 RNAi decreases endothelial cell proliferation and tubular differentiation that are essential steps in the angiogenesis process.

The important implications of VGSCs in cancer progression and invasion led Litan and Langhans 51 to express that cancer is a channelopathy (For further reading on structure and functions of VGSC see reference 52).

Material and methods

A search was performed in the medical literature to find pharmaceuticals already in use for other purposes than cancer, that as an off-target effect could inhibit VSGCs and to determine if these pharmaceuticals can actually decrease migration, invasion and metastatic potential of cancer. A Pubmed advanced search retrieved 50519 articles under the search condition “voltage-gated sodium channel blocker” during the period of 1981–2015.

The articles that considered drugs that were not in clinical use or FDA-approved were not included in this study, with the exception of resveratrol and natural polyphenols.

The following drugs fulfilling these criteria were found: phenytoin, carbamazepine, lamotrigine valproate, ranolazine, resveratrol, ropivacaine, lidocaine, mexiletine, flunarizine, and riluzole.

A new search was performed in Pubmed for each of the above listed pharmaceuticals with two search criteria: 1) the drug and 2) the term cancer. The period considered was from 1962 to the current time.

Those VGSC blocking drugs that exhibited anti-cancer activity based mainly by other mechanisms are only briefly mentioned; valproic acid and lamotrigine probably act against cancer by histone deacetylase inhibition and riluzole’s anti-cancer mechanism is probably related to the glutamatergic pathway.

Tetrodotoxin is also analyzed in spite of the fact that it is not in clinical use, because it is the traditional model molecule of VGSC blocking, against which other drugs are comparatively tested in the experimental setting.

Results

Tetrodotoxin (TTX)

Many biological toxins like those found in scorpions and sea anemones develop their toxicity by introducing modifications to the properties of VGSCs 52. This toxicity can be achieved by inactivation of VGSCs (as in the case of TTX) or on the contrary by persistent activation of the channel (in the case of veratridine, acinitine and many others).

TTX is a powerful biological neurotoxin found in fishes of the Tetraodontiformes order and certain symbiotic bacteria. TTX binds to VGSCs and blocks its activity, mainly in the nervous system. It is used as a biotoxin for defensive or predatory purposes. TTX binds to the extracellular portion of VGSC, disabling the function of the ion channel and results in a very poisonous effect producing death through respiratory paralysis 22.

Due to its high toxicity it is not used as a therapeutic agent, but TTX has been very useful in the experimental setting for the study of VGSCs physiology.

Phenytoin (Diphenylhydantoin; PHEN)

PHEN is an anticonvulsant that has been identified as a sodium channel blocker 53, 54 which has been held responsible for inducing lymphoma, pseudolymphoma, hematological malignancies and other cancers in patients under chronic treatment 55. This carcinogenic effect of phenytoin was not confirmed in large epidemiological studies 56. PHEN diminishes cell mediated immunity 57.

Vernillo et al. in 1990 58 found that phenytoin inhibited bone resorption in rat osteosarcoma cells through significant reduction of collagenase and gelatinase activities. But Dyce et al. 59 did not find evidence of PHEN’s gelatinase inhibitory activity in B16 melanoma cells in vitro. This may be evidence of tissue-specific activity which has not been investigated any further. Dyce et al. did not find important anti-metastatic activity either in a melanoma tail injection model in mice. But when the data of this publication is examined in detail, it seems that the anti-metastatic activity is not so low as mentioned by the authors: they found that after injection of tumor cells in the mice protected with PHEN, the animal developed mean pulmonary colonies 4.6 +/- 3.1 but when the mice received no PHEN, developed. 10.2 +/- 9.9 colonies. Beyond any statistical analysis the difference seems important.

Yang et al. 60 found that NaV 1.5 was over-expressed in breast cancer cells with high metastatic potential, and the anticonvulsivant PHEN had the ability to reduce migration and invasion at clinically achievable concentrations in MDA-MB-231 cells (which are strongly metastatic) and showed no effects on MCF-7 cells with low metastatic potential.

PHEN blocks Na + channels and has a high affinity for VGSCs in the inactivated state of the channel 61. Compared with verapamil, lidocaine and carbamacepine, PHEN had an intermediate potency between verapamil and lidocaine, being verapamil the strongest inhibitor and carbamazepine the weakest.

Abdul et al. 62 studied the effect of four anticonvulsants (PHEN, carbamazepine, valproate and ethosuxinide) on the secretion of prostate specific antigen and interleukin-6 in different human prostate cancer cell lines. PHEN and carbamazepine inhibited the secretion of both.

Fadiel et al. 63 found that PHEN is a strong estrogen receptor α antagonist at clinically achievable concentrations and at the same time is a weak agonist.

Table 2. Summary of PHEN’s activity against cancer and metastasis.

| Reference | Findings |

|---|---|

| Nelson, 2015 64 | PHEN at clinically achievable concentration reduces breast cancer growth, invasion and metastasis

in vivo in

a xenograft model. |

| Yang M, 2012 60 | At clinically achievable concentration PHEN inhibited migration and invasion of highly metastatic breast

cancer MDA-MB-231 cell line, and had no effect on MCF-7 cell line which has a low metastatic potential and do not express VGSCs. |

| Lee Ts, 2010 65 | DPTH-N10 a phenytoin derivate drug, inhibits proliferation of COLO 205 colon cancer cell line. |

| Lyu Y, 2008 66 | DPTH-N10 a phenytoin derivate drug, shows strong anti-angiogenic activity. Inhibits HUVEC proliferation and

capillary like tube formation. |

| Sikes, 2003 67 | New VGSC blockers based on PHEN, showed increased inhibition of prostate cancer growth. |

| Anderson, 2003 68 | Developed new VGSC blockers based on the PHEN binding site study. These new VGSC blockers showed

potent inhibition of prostate cancer cells growth (Androgen independent PC3 line). |

| Fraser, 2003 36 | PHEN decreased motility of prostate cancer cells. |

| Abdul, 2001 62 | PHEN and carbamazepine decreased PSA secretion in human prostate carcinoma cell lines. |

| Lobert, 1999 69 | PHEN has inhibitory effects on microtubule assembly and has additive effects with vinblastine. |

| Kawamura, 1996 70 | PHEN potentiates vinblastine citotoxicity. |

| Sato K, 1994 31 | PHEN decreased growth of MIA PaCa-2 (pancreatic cancer cells). |

| Lang DG, 1993 71 | PHEN, Carbamazepine and lamotrigine are inhibitors of sodium channels and reduces glutamate release in

rat neuroblastoma cells. |

| Tittle, 1992 72 | PHEN decreased growth in six murine tumor cell lines of lymphoid origin. |

There is an undesired side effect of PHEN that may represent a drawback for its use in cancer: immunological depression 73– 76. This is an issue that deserves further research. Finally it has to be mentioned that PHEN interacts with many other pharmaceuticals, particularly those usually employed in chemotherapy.

In summary, the main activities developed by PHEN in relation with cancer are:

VGSC blocking, microtubule polymerization blocking, immunosuppression, calcium channel blocking and enhancement of vinblastine cytotoxicity.

Carbamazepine

Carbamazepine is a sodium channel blocker, pro-autophagy agent and histone deacetylase inhibitor that has been in use since 1962 for the treatment of seizures, neuropathic pain and bipolar disorders and has shown interesting anti-metastatic potential in the experimental setting 77. Studies have also insinuated preventative effects in prostate cancer 78.

Carbamazepine induces Her2 protein degradation through the proteosome without modifying its production 79. This activity seems to be related to histone deacetylase inhibition rather than VGSC blocking. Growth inhibition in estrogen-receptor positive breast cancer cell lines seems probably a histone deacetylase inhibitor effect 80.

Oxcarbazepine, a molecule related to carbamazepine is also a sodium channel blocker 81 and a potassium channel blocker, but it has not been investigated for cancer.

The anti-cancer mechanisms shown by carbamazepine are in summary:

Valproic acid (VAL)

An anticonvulsivant drug that exerts multiple actions related to anti-cancer effects: calcium channel blocker, VGSC blocker, inhibition of histone deacetylase, potentiation of inhibitory activity of GABA, decreases angiogenesis, interferes with MAP kinase pathways and the β catenin-Wnt pathway 83. Val is being tested in various clinical trials in leukemias and solid tumors 84. Most of the anti-tumor activities of VAL seem to be related to the inhibition of histone deacetylase rather than VGSC blocking and further discussion goes beyond the scope of this review.

Ranolazine

Ranolazine, (Ranexa) is an antiarrhythmic drug indicated for the treatment of chronic angina that was first approved by FDA in 2006. Common side effects are dizziness, constipation, headache and nausea 85.

Ranolazine inhibits the late inward sodium current in heart muscle, so that it works as a sodium channel inhibitor. Ranolazine is metabolized by the CYP3A enzyme.

Driffort et al. 86 demonstrated that ranolazine inhibition of NaV1.5 reduced breast cancer cells invasiveness in vivo and in vitro using the highly invasive MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line. This drug also efficiently decreased the activity of the embryonic/neonatal isoform of NaV1.5 (the active isoform usually found in human breast cancer cells). Ranolazine did not change the viability of the cell. It also decreased the pro-invasive morphology of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. They also demonstrated that injection of cancer cells through the tail vein of nude mice at non-toxic doses achieved a significant reduction in metastatic colonization.

Resveratrol and other polyphenols

Certain biologically active natural phenols like resveratrol and genistein have shown effects on VGSCs, increasing hyperpolarized potentials during steady state inactivation 88.

Resveratrol’s inhibitory effects on VGSC has consequences for the behaviour of metastatic cells. Fraser et al. 89 showed that resveratrol significantly decreased lateral and transversal motility and invasion capacity of rat prostate cancer cells (MAT-Ly-Lu cells), without changes in cellular viability. They also found that resveratrol inhibited VGSC in a dose-dependent manner and using TTX with resveratrol did not increase VGSC inhibition nor metastatic cell behavior. Resveratrol also inhibits epithelial sodium channels 90.

Resveratrol is not the only polyphenol with VGSC blocking activity: quercetin and catechin showed similar effects 91 in ventricular myocytes and genistein in rat cervical ganglia 92 and nociceptive neurons 93.

Gabapentin

Gabapentin is used for the treatment of pain and decreases expression of NaV1.7 and ERK-1/ERK-2 in ganglion neurons 94, 95 and expression of NaV1.2 96. We found no publications about gabapentin as a possible anti-metastasis or anti-invasion treatment.

Riluzole

Riluzole is a drug used for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and it is a known sodium channel blocker. This effect was demonstrated in human prostate cancer cell lines 97. Most likely, the anticancer activity of riluzole is mainly related to other anticancer characteristics of this drug like downregulation of the glutamatergic pathway 98.

Flunarizine

Flunarizine is a calcium channel blocker with a long plasma half-life, used in migraine prevention, vertigo and adjuvant treatment of epilepsy, but has shown important activity as a VGSC blocker 99– 101. It binds calmodulin.

At low temperatures (22 degrees) flunarizine potentiate the binding of phenytoin to VGSC 102.

Flunarizine has shown anti-cancer activities in lymphoma and multiple myeloma 103, and leukaemia 104, but these anti-cancer activities were apparently related to induction of apoptosis, which is not a consequence of VGSC blockage. On melanoma cells, flunarizine showed decreased motility and invasion in vitro 105, 106 . Flunarizine inhibited migration and phagocytosis in B16 melanoma cells and M5076 macrophage-like cancer cells 107.

According to data found in medical literature we may consider anti-cancer activities of flunarizine in the following way:

-

a)

Activities dependent on VGSC blocking: decreased motility and invasion 105– 107.

-

b)

Activities dependent on calcium channel blocking: vasodilatation and increased concentration of chemotherapeutic drugs in tumor tissues 108– 110, and increased radiosensitivity due to better oxygen delivery to anoxic areas of the tumor 111.

-

c)

WNT inhibition 103.

-

d)

Inhibition of lymphangiogenesis 112.

-

e)

Increase of melphalan`s citotoxicity in resistant ovarian cancer cells 113 and in rhabdomyosarcoma 114.

-

f)

Positive modulation of doxorubicin in multidrug resistant phenotype colon adenocarcinoma cells 115.

-

g)

Decreased blood viscosity improving oxygen delivery to the tumor 116.

-

h)

Other anti-tumor activities: apoptosis and growth rate inhibition 103, 104, 117.

Flunarizine has not been tested in cancer trials. The fact that it can significantly reduce motility in melanoma cells which is a highly metastasizing tumor and is also an inhibitor of lymphangiogenesis, makes it an interesting adjuvant therapy that deserves further research. The possible synergy with phenytoin is also an issue that should be explored.

However, flunarizine has also shown cytoprotective effects in certain tissues (auditory cells) against cisplatin 118 and flunarizine may induce Nrf-2 overexpression that confers resistance to chemotherapy in some tumors like Her2 positive breast cancer 119.

Local anaesthetics

Local anaesthetics eliminate pain through VGSC blocking on nociceptive neurones.

Local anaesthetics like lidocaine have shown interesting anti-cancer effects in various cancer cells. Lidocaine is a VGSC blocker. The mechanisms involved in decreased proliferation seems related to the inhibitory actions of local anaesthetics on EGFR 120 rather than VGSC blocking. Inhibition of invasion found in cancer cells treated with lidocaine (HT1080, HOS, and RPMI-7951) by Mammoto et al. was attributed by the authors to shedding of the extracellular domain of heparin binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor and not to VGSC blocking 121.

Baptista-Hon et al. described a decrease in metastatic potential of colon cancer cells (SW620 cells) by ropivacaine and decrease of Nav1.5 function (adult and neonatal isoforms) 122.

Piegeler et al., 2012 identified decreased Src activity produced by amide-linked anaesthetics as an independent mechanism of migration and invasion decrease 123.

Other drugs

Other drugs that have shown significant VGSC blocking activity and may have activity in the fight against migration, invasion and metastasis are: fluoxetin blocks NaV1.5 124, and mexiletine 125.

Intravenous propofol has been recognized as an anti-invasion drug in HeLa, HT1080, HOS and RPMI-75 cells by decreasing actin stress-fiber formation and focal adhesion inhibition, but this drug is not a VGSC blocker and the probable mechanism is through Rho-A modulation 126.

All of the drugs we have mentioned are low cost pharmaceuticals, have predictable and well known side effects, and therefore they are adequate candidates for further clinical trials.

Discussion

Functionally active VGSCs are expressed in many metastatic cancer cells. This functional expression is an integral element of the metastatic process in many different solid tumors.

The essential role of this protein in invadopodia has been established, so VGSCs became a legitimate target to decrease migration, invasion and metastasis. Repurposed drugs like anticonvulsants, (phenytoin in particular) have shown interesting anti-invasion effects.

Carbamazepine’s ability to induce Her2 protein degradation should be considered an interesting association to trastuzumab.

Targeting VGSCs may act in synergy with anti-angiogenic treatments and with other chemotherapeutic drugs like vinblastine.

On the other hand in the review by Besson et al. 127 there is a very important remark: VGSC is also present in macrophages and cells related with the immunologic system, so that disrupting VGSC`s activity may deteriorate also anti-tumor immunologic mechanisms.

Flunarizine represents a particularly interesting molecule because it may attack cancer from four different angles: invasion and migration through VGSC blocking, WNT pathway down-regulation, decreased lymphangiogenesis and better oxygenation of hypoxic areas which permits a better arrival of chemotherapeutic drugs and increased sensitivity to radiation. It has never been tested in clinical trials for cancer treatment.

Future directions

New VGSCs blockers are under research. Sikes et al. 67 developed new blockers based on the phenytoin binding site to VGSC. They found compounds with enhanced activity in VGSC blocking and antitumor activity against human prostate cancer cells.

The association of two or more VGSC blockers may show synergistic enhanced anti-metastatic activity. Nerve growth factor (NGF) increases the number of VGSCs 129; tanezumab, a new NGF inhibitor diminishes the amount of VGSCs 128, so we may assume that tanezumab may develop synergistic activity with VGSC blockers. Tanezumab has not been tested in cancer and we think it deserves more research because NGF is also an anti-apoptotic protein 130.

Stettner et al. 134 found that men over 50 years of age may be benefited with the use of anticonvulsivants, regarding prostate cancer prevention because they observed lower PSA levels compared with control groups. They also described a ranking of this preventive activity: valproic acid>levetiracetam>carbamazepine/oxcarbazepine>lamotrigine. The authors also observed synergy between these drugs.

Conclusions

Repurposed VGSC blocker drugs, particularly phenytoin, flunarizine and polyphenols, deserve clinical trials as complementary treatment to decrease the metastatic risk.

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no funds were involved in supporting this work.

[version 1; referees: 2 approved]

References

- 1. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA: Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–74. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mehlen P, Puisieux A: Metastasis: a question of life or death. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(6):449–458. 10.1038/nrc1886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Taketo MM: Reflections on the spread of metastasis to cancer prevention. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2011;4(3):324–328. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pavese JM, Krishna SN, Bergan RC: Genistein inhibits human prostate cancer cell detachment, invasion, and metastasis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;100(Suppl 1):431S–436S. 10.3945/ajcn.113.071290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yang X, Li X, Ren J: From French Paradox to cancer treatment: anti-cancer activities and mechanisms of resveratrol. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2014;14(6):806–25. 10.2174/1871520614666140521121722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Xiong A, Yang Z, Shen Y, et al. : Transcription Factor STAT3 as a Novel Molecular Target for Cancer Prevention. Cancers (Basel). 2014;6(2):926–57. 10.3390/cancers6020926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kronski E, Fiori ME, Barbieri O, et al. : miR181b is induced by the chemopreventive polyphenol curcumin and inhibits breast cancer metastasis via down-regulation of the inflammatory cytokines CXCL1 and -2. Mol Oncol. 2014;8(3):581–95. 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Langley RE, Rothwell PM: Aspirin in gastrointestinal oncology: new data on an old friend. Curr Opin Oncol. 2014;26(4):441–7. 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Li WW, Long GX, Liu DB, et al. : Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor celecoxib suppresses invasion and migration of nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell lines through a decrease in matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 activity. Pharmazie. 2014;69(2):132–7. 10.1691/ph.2014.3794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gebremeskel S, LeVatte T, Liwski RS, et al. : The reversible P2Y12 inhibitor ticagrelor inhibits metastasis and improves survival in mouse models of cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(1):234–40. 10.1002/ijc.28947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Li J, Oupický D: Effect of biodegradability on CXCR4 antagonism, transfection efficacy and antimetastatic activity of polymeric Plerixafor. Biomaterials. 2014;35(21):5572–9. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu Y, Yu T, Liang H, et al. : Nitric oxide inhibits hetero-adhesion of cancer cells to endothelial cells: restraining circulating tumor cells from initiating metastatic cascade. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4344. 10.1038/srep04344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang J, Chen J, Wan L, et al. : Synthesis, spectral characterization, and in vitro cellular activities of metapristone, a potential cancer metastatic chemopreventive agent derived from mifepristone (RU486). AAPS J. 2014;16(2):289–98. 10.1208/s12248-013-9559-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ardiani A, Gameiro SR, Palena C, et al. : Vaccine-mediated immunotherapy directed against a transcription factor driving the metastatic process. Cancer Res. 2014;74(7):1945–57. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-2045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhang J, Zhao C, Gao Y, et al. : Thiabendazole, a well-known antifungal drug, exhibits anti-metastatic melanoma B16F10 activity via inhibiting VEGF expression and inducing apoptosis. Pharmazie. 2013;68(12):962–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rietkötter E, Menck K, Bleckmann A, et al. : Zoledronic acid inhibits macrophage/microglia-assisted breast cancer cell invasion. Oncotarget. 2013;4(9):1449–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rolfo C, Raez LE, Russo A, et al. : Molecular target therapy for bone metastasis: starting a new era with denosumab, a RANKL inhibitor. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2014;14(1):15–26. 10.1517/14712598.2013.843667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. NCT01952054, NCT01951586, NCT02129699. Reference Source [Google Scholar]

- 19. Catterall WA: Voltage-gated sodium channels at 60: structure, function and pathophysiology. J Physiol. 2012;590(Pt 11):2577–2589. 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Termin A, Martinborough E, Wilson D: Chapter 3 – Recent Advances in Voltage-Gated Sodium Channel Blockers: Therapeutic Potential as Drug Targets in the CNS. Annu Rep Med Chem. 2008;43:43–60. 10.1016/S0065-7743(08)00003-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brackenbury WJ: Voltage-gated sodium channels and metastatic disease. Channels (Austin). 2012;6(5):352–361. 10.4161/chan.21910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lee CH, Ruben PC: Interaction between voltage-gated sodium channels and the neurotoxin, tetrodotoxin. Channels (Austin). 2008;2(6):407–412. 10.4161/chan.2.6.7429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fraser SP, Diss JK, Chioni AM, et al. : Voltage-gated sodium channel expression and potentiation of human breast cancer metastasis. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(15):5381–9. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roger S, Rollin J, Barascu A: Voltage-gated sodium channels potentiate the invasive capacities of human non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2007;39(4):774–786. 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blandino JK, Viglione MP, Bradley WA, et al. : Voltage-dependent sodium channels in human small-cell lung cancer cells: role in action potentials and inhibition by Lambert-Eaton syndrome IgG. J Membr Biol. 1995;143(2):153–163. 10.1007/BF00234661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Diaz D, Delgadillo DM, Hernández-Gallegos E, et al. : Functional expression of voltage-gated sodium channels in primary cultures of human cervical cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210(2):469–478. 10.1002/jcp.20871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bennett ES, Smith BA, Harper JM: Voltage-gated Na + channels confer invasive properties on human prostate cancer cells. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447(6):908–914. 10.1007/s00424-003-1205-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gao R, Shen Y, Cai J, et al. : Expression of voltage-gated sodium channel alpha subunit in human ovarian cancer. Oncol Rep. 2010;23(5):1293–1299. 10.3892/or_00000763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. House CD, Vaske CJ, Schwartz AM, et al. : Voltage-gated Na + channel SCN5A is a key regulator of a gene transcriptional network that controls colon cancer invasion. Cancer Res. 2010;70(17):6957–67. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fraser SP, Diss JK, Lloyd LJ, et al. : T-lymphocyte invasiveness: control by voltage-gated Na + channel activity. FEBS Lett. 2004;569(1-3):191–194. 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.05.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sato K, Ishizuka J, Cooper CW, et al. : Inhibitory effect of calcium channel blockers on growth of pancreatic cancer cells. Pancreas. 1994;9(2):193–202. 10.1097/00006676-199403000-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fulgenzi G, Graciotti L, Faronato M, et al. : Human neoplastic mesothelial cells express voltage-gated sodium channels involved in cell motility. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(7):1146–1159. 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grimes JA, Fraser SP, Stephens GJ, et al. : Differential expression of voltage-activated Na + currents in two prostatic tumour cell lines: contribution to invasiveness in vitro. FEBS Lett. 1995;369(2-3):290–294. 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00772-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Laniado ME, Lalani EN, Fraser SP: Expression and functional analysis of Voltage-activated Na + channels in human prostate cancer cell lines and their contribution to invasion in vitro. Am J Pathol. 1997;150(4):1213–1221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Smith P, Rhodes NP, Shortland AP, et al. : Sodium channel protein expression enhances the invasiveness of rat and human prostate cancer cells. FEBS Lett. 1998;423(1):19–24. 10.1016/S0014-5793(98)00050-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fraser SP, Salvador V, Manning EA, et al. : Contribution of functional voltage-gated Na + channel expression to cell behaviors involved in the metastatic cascade in rat prostate cancer: I. Lateral motility. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195(3):479–87. 10.1002/jcp.10312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roger S, Besson P, Le Guennec JY: Involvement of a novel fast inward sodium current in the invasion capacity of a breast cancer cell line. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1616(2):107–111. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Batcioglu K, Uyumlu AB, Satilmis B, et al. : Oxidative stress in the in vivo DMBA rat model of breast cancer: suppression by a voltage-gated sodium channel inhibitor (RS100642). Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;111(2):137–41. 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2012.00880.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Brisson L, Driffort V, Benoist L, et al. : Na v1.5 Na + channels allosterically regulate the NHE-1 exchanger and promote the activity of breast cancer cell invadopodia. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 21):4835–4842. 10.1242/jcs.123901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gillet L, Roger S, Besson P, et al. : Voltage-gated Sodium Channel Activity Promotes Cysteine Cathepsin-dependent Invasiveness and Colony Growth of Human Cancer Cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(13):8680–8691. 10.1074/jbc.M806891200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mader CC, Oser M, Magalhaes MA, et al. : An EGFR-Src-Arg-Cortactin pathway mediates functional maturation of invadopodia and breast cancer cell invasion. Cancer Res. 2011;71(5):1730–1741. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Clark ES, Whigham AS, Yarbrough WG, et al. : Cortactin is an essential regulator of matrix metalloproteinase secretion and extracellular matrix degradation in invadopodia. Cancer Res. 2007;67(9):4227–35. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Murphy DA, Courtneidge MA: The ‘ins’ and ‘outs’ of podosomes and invadopodia: characteristics, formation and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(7):413–426. 10.1038/nrm3141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cosen-Binker LI, Kapus A: Cortactin: the gray eminence of the cytoskeleton. Physiology (Bethesda). 2006;21:352–361. 10.1152/physiol.00012.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Onganer PU, Djamgoz MB: Small-cell lung cancer (human): potentiation of endocytic membrane activity by voltage-gated Na + channel expression in vitro. J Membr Biol. 2005;204(2):67–75. 10.1007/s00232-005-0747-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tarone G, Cirillo D, Giancotti FG, et al. : Rous sarcoma virus-transformed fibroblasts adhere primarily at discrete protrusions of the ventral membrane called podosomes. Exp Cell Res. 1985;159(1):141–57. 10.1016/S0014-4827(85)80044-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Berdeaux RL, Diaz B, Kim L, et al. : Active Rho is localized to podosomes induced by oncogenic Src and is required for their assembly and function. J Cell Biol. 2004;166(3):317–323. 10.1083/jcb.200312168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Dulong C, Fang YJ, Gest C, et al. : The small GTPase RhoA regulates the expression and function of the sodium channel Nav1.5 in breast cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2014;44(2):539–547. 10.3892/ijo.2013.2214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Timpson P, McGhee EJ, Morton JP, et al. : Spatial regulation of RhoA activity during pancreatic cancer cell invasion driven by mutant p53. Cancer Res. 2011;71(3):747–757. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Andrikopoulos P, Fraser SP, Patterson L, et al. : Angiogenic functions of voltage-gated Na + Channels in human endothelial cells: modulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) signaling. J Biol Chem. 2011;286(19):16846–16860. 10.1074/jbc.M110.187559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Litan A, Langhans SA: Cancer as a channelopaty: ion channels and pumps in tumor development and progression. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015;9:86. 10.3389/fncel.2015.00086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Denac H, Mevissen M, Scholtysik G, et al. : Structure, function and pharmacology of voltage-gated sodium channels. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2000;362(6):453–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Matsuki N, Quandt FN, Ten Eick RE, et al. : Characterization of the block of sodium channels by phenytoin in mouse neuroblastoma cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;228(2):523–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Willow M, Gonoi T, Catterall WA, et al. : Voltage clamp analysis of the inhibitory actions of diphenylhydantoin and carbamazepine on voltage-sensitive sodium channels in neuroblastoma cells. Mol Pharmacol. 1985;27(5):549–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schwinghammer TL, Howrie DL: Phenytoin-induced lymphadenopathy. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1983;17(6):460–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Olsen JH, Boyce JD, Jr, Jenssen JP, et al. : Cancer among epileptic patients exposed to anticonvulsant drugs. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(10):803–8. 10.1093/jnci/81.10.803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Okamoto Y, Shimizu K, Tamura K, et al. : Effects of phenytoin on cell-mediated immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 1988;26(2):176–9. 10.1007/BF00205612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vernillo AT, Ramamurthy NS, Lee HM, et al. : The effect of phenytoin on collagenase and gelatinase activities in UMR 106-01 rat osteoblastic osteosarcoma cells. Matrix. 1990;10(1):27–32. 10.1016/S0934-8832(11)80134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Dyce M, Sharif SF, Whalen GF, et al. : Search for anti-metastatic therapy: effects of phenytoin on B16 melanoma metastasis. J Surg Oncol. 1992;49(2):107–12. 10.1002/jso.2930490209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yang M, Kozminski DJ, Wold LA, et al. : Therapeutic potential for phenytoin: targeting Na v 1.5 sodium channels to reduce migration and invasion in metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;134(2):603–615. 10.1007/s10549-012-2102-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ragsdale DS, Scheuer T, Catterall WA, et al. : Frequency and voltage dependent inhibition of type IIA Na + channels, expressed in a mammalian cell line by local anesthetic, antiarrhytmic and anticonvulsivant drugs. Mol Pharmacol. 1991;40(5):756–765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Abdul M, Hoosein N: Inhibition by anticonvulsants of prostate-specific antigen and interleukin-6 secretion by human prostate cancer cells. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(3B):2045–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Fadiel A, Song J, Tivon D, et al. : Phenytoin is an estrogen receptor α-selective modulator that interacts with helix 12. Reprod Sci. 2015;22(2):146–55. 10.1177/1933719114549853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Nelson M, Yang M, Dowle AA, et al. : The sodium channel-blocking antiepileptic drug phenytoin inhibits breast tumour growth and metastasis. Mol Cancer. 2015;14(1):13. 10.1186/s12943-014-0277-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lee TS, Chen LC, Liu Y, et al. : 5,5-Diphenyl-2-thiohydantoin-N10 (DPTH-N10) suppresses proliferation of cultured colon cancer cell line COLO-205 by inhibiting DNA synthesis and activating apoptosis. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2010;382(1):43–50. 10.1007/s00210-010-0519-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Liu Y, Wu J, Ho PY, et al. : Anti-angiogenic action of 5,5-diphenyl-2-thiohydantoin-N10 (DPTH-N10). Cancer Lett. 2008;271(2):294–305. 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sikes RA, Walls AM, Brennen WN, et al. : Therapeutic approaches targeting prostate cancer progression using novel voltage-gated ion channel blockers. Clin Prostate Cancer. 2003;2(3):181–187. 10.3816/CGC.2003.n.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Anderson JD, Hansen TP, Lenkowski PW, et al. : Voltage-gated sodium channel blockers as cytostatic inhibitors of the androgen-independent prostate cancer cell line PC-3. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2(11):1149–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Lobert S, Ingram JW, Correia JJ, et al. : Additivity of dilantin and vinblastine inhibitory effects on microtubule assembly. Cancer Res. 1999;59(19):4816–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kawamura KI, Grabowski D, Weizer K, et al. : Modulation of vinblastine cytotoxicity by dilantin (phenytoin) or the protein phosphatase inhibitor okadaic acid involves the potentiation of anti-mitotic effects and induction of apoptosis in human tumour cells. Br J Cancer. 1996;73(2):183–8. 10.1038/bjc.1996.33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Lang DG, Wang CM, Cooper BR: Lamotrigine, phenytoin and carbamazepine interactions on the sodium current present in N4TG1 mouse neuroblastoma cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266(2):829–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Tittle TV, Schaumann BA, Rainey JE, et al. : Segregation of the growth slowing effects of valproic acid from phenytoin and carbamazepine on lymphoid tumor cells. Life Sci. 1992;50(14):PL79–83. 10.1016/0024-3205(92)90104-W [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dosch HM, Jason J, Gelfand EW: Transient antibody deficiency and abnormal t-suppressor cells induced by phenytoin. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(7):406–409. 10.1056/NEJM198202183060707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sorrell TC, Forbes IJ: Depression of immune competence by phenytoin and carbamazepine. Studies in vivo and in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 1975;20(2):273–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Fontana A, Grob PJ, Sauter R, et al. : IgA deficiency, epilepsy, and hydantoin medication. Lancet. 1976;2(7979):228–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(76)91028-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Marcoli M, Gatti G, Ippoliti G, et al. : Effect of chronic anticonvulsant monotherapy on lymphocyte subpopulations in adult epileptic patients. Hum Toxicol. 1985;4(2):147–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Teichmann M, Kretschy N, Kopf S, et al. : Inhibition of tumour spheroid-induced prometastatic intravasation gates in the lymph endothelial cell barrier by carbamazepine: drug testing in a 3D model. Arch Toxicol. 2014;88(3):691–9. 10.1007/s00204-013-1183-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Stettner M, Krämer G, Strauss A, et al. : Long-term antiepileptic treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors may reduce the risk of prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21(1):55–64. 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32834a7e6f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Meng Q, Chen X, Sun L, et al. : Carbamazepine promotes Her-2 protein degradation in breast cancer cells by modulating HDAC6 activity and acetylation of Hsp90. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;348(1–2):165–71. 10.1007/s11010-010-0651-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Meng QW, Zhao CH, Xi YH, et al. : [Inhibitory effect of carbamazepine on proliferation of estrogen-dependent breast cancer cells]. Ai Zheng. 2006;25(8):967–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Huang CW, Huang CC, Lin MW, et al. : The synergistic inhibitory actions of oxcarbazepine on voltage-gated sodium and potassium currents in differentiated NG108-15 neuronal cells and model neurons. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11(5):597–610. 10.1017/S1461145707008346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Beutler AS, Li SD, Nicol R, et al. : Carbamazepine is an inhibitor of histone deacetylases. Life Sci. 2005;76(26):3107–3115. 10.1016/j.lfs.2005.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kostrouchová M, Kostrouch Z, Kostrouchová M: Valproic acid, a molecular lead to multiple regulatory pathways. Folia Biol (Praha). 2007;53(2):37–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Michaelis M, Doerr HW, Cinatl J, Jr: Valproic acid as anti-cancer drug. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(33):3378–93. 10.2174/138161207782360528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Banon D, Filion KB, Budlovsky T, et al. : The usefulness of ranolazine for the treatment of refractory chronic stable angina pectoris as determined from a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(6):1075–1082. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.11.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Driffort V, Gillet L, Bon E, et al. : Ranolazine inhibits Na V1.5-mediated breast cancer cell invasiveness and lung colonization. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:264. 10.1186/1476-4598-13-264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Djamgoz MB, Onkal R: Persistent current blockers of voltage-gated sodium channels: a clinical opportunity for controlling metastatic disease. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov. 2013;8(1):66–84. 10.2174/1574892811308010066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Ingolfsson HI, Thakur P, Herold KF, et al. : Phytochemicals perturb membranes and promiscuously alter protein function. ACS Chem Biol. 2014;9(8):1788–1798. 10.1021/cb500086e [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Fraser SP, Peters A, Fleming-Jones S, et al. : Resveratrol: inhibitory effects on metastatic cell behaviors and voltage-gated Na + channel activity in rat prostate cancer in vitro. Nutr Cancer. 2014;66(6):1047–58. 10.1080/01635581.2014.939291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Weixel KM, Marciszyn A, Alzamora R, et al. : Resveratrol inhibits the epithelial sodium channel via phopshoinositides and AMP-activated protein kinase in kidney collecting duct cells. Plos One. 2013;8(19):e78019. 10.1371/journal.pone.0078019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Wallace CH, Baczkó I, Jones L, et al. : Inhibition of cardiac voltage-gated sodium channels by grape polyphenols. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149(6):657–665. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Jia Z, Jia Y, Liu B, et al. : Genistein inhibits voltage-gated sodium currents in SCG neurons through protein tyrosine kinase-dependent and kinase-independent mechanisms. Pflugers Arch. 2008;456(5):857–66. 10.1007/s00424-008-0444-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Liu L, Yang T, Simon SA: The protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor, genistein, decreases excitability of nociceptive neurons. Pain. 2004;112(1–2):131–41. 10.1016/j.pain.2004.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Zhang JL, Yang JP, Zhang JR, et al. : Gabapentin reduces allodynia and hyperalgesia in painful diabetic neuropathy rats by decreasing expression level of Nav1.7 and p-ERK1/2 in DRG neurons. Brain Res. 2013;1493:13–8. 10.1016/j.brainres.2012.11.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Yang RH, Wang WT, Chen JY, et al. : Gabapentin selectively reduces persistent sodium current in injured type-A dorsal root ganglion neurons. Pain. 2009;143(1–2):48–55. 10.1016/j.pain.2009.01.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Liu Y, Qin N, Reitz T, et al. : Inhibition of the rat brain sodium channel Nav1.2 after prolonged exposure to gabapentin. Epilepsy Res. 2006;70(2–3):263–8. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Abdul M, Hoosein N: Voltage-gated sodium ion channels in prostate cancer: expression and activity. Anticancer Res. 2002;22(3):1727–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Wall BA, Wangari-Talbot J, Shin SS, et al. : Disruption of GRM1-mediated signalling using riluzole results in DNA damage in melanoma cells. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27(2):263–74. 10.1111/pcmr.12207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Kiskin NI, Chizhmakov IV, Tsyndrenko AYa, et al. : R56865 and flunarizine as Na +-channel blockers in isolated Purkinje neurons of rat cerebellum. Neuroscience. 1993;54(3):575–85. 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90229-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Fischer W, Kittner H, Regenthal R, et al. : Anticonvulsant profile of flunarizine and relation to Na + channel blocking effects. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2004;94(2):79–88. 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2004.pto940205.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ye Q, Yan LY, Xue LJ, et al. : Flunarizine blocks voltage-gated Na + and Ca 2+ currents in cultured rat cortical neurons: A possible locus of action in the prevention of migraine. Neurosci Lett. 2011;487(3):394–9. 10.1016/j.neulet.2010.10.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Francis J, Burnham WM: [3H]Phenytoin identifies a novel anticonvulsant-binding domain on voltage-dependent sodium channels. Mol Pharmacol. 1992;42(6):1097–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Schmeel LC, Schmeel FC, Kim Y, et al. : Flunarizine exhibits in vitro efficacy against lymphoma and multiple myeloma cells. Anticancer Res. 2015;35(3):1369–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Conrad DM, Furlong SJ, Doucette CD, et al. : The Ca 2+ channel blocker flunarizine induces caspase-10-dependent apoptosis in Jurkat T-leukemia cells. Apoptosis. 2010;15(5):597–607. 10.1007/s10495-010-0454-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Fink-Puches R, Helige C, Kerl H, et al. : Inhibition of melanoma cell directional migration in vitro via different cellular targets. Exp Dermatol. 1993;2(1):17–24. 10.1111/j.1600-0625.1993.tb00194.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Hofmann-Wellenhof R, Fink-Puches R, Smolle J, et al. : Correlation of melanoma cell motility and invasion in vitro. Melanoma Res. 1995;5(5):311–9. 10.1097/00008390-199510000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Sezzi ML, De Luca G, Materazzi M, et al. : Effects of a calcium-antagonist (flunarizine) on cancer cell movement and phagocytosis. Anticancer Res. 1985;5(3):265–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Kaelin WG, Jr, Shrivastav S, Jirtle RL: Blood flow to primary tumors and lymph node metastases in SMT-2A tumor-bearing rats following intravenous flunarizine. Cancer Res. 1984;44(3):896–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Bellelli A, Camboni C, de Luca G, et al. : In vitro and in vivo enhancement of vincristine antitumor activity on B16 melanoma cells by calcium antagonist flunarizine. Oncology. 1987;44(1):17–23. 10.1159/000226436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Vaupel P, Menke H: Blood flow, vascular resistance and oxygen availability in malignant tumours upon intravenous flunarizine. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1987;215:393–8. 10.1007/978-1-4684-7433-6_48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Wood PJ, Hirst DG: Cinnarizine and flunarizine as radiation sensitisers in two murine tumours. Br J Cancer. 1988;58(6):742–745. 10.1038/bjc.1988.301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Astin JW, Jamieson SM, Eng TC, et al. : An in vivo antilymphatic screen in zebrafish identifies novel inhibitors of mammalian lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic-mediated metastasis. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(10):2450–62. 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0469-T [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Gornati D, Zaffaroni N, Villa R, et al. : Modulation of melphalan and cisplatin cytotoxicity in human ovarian cancer cells resistant to alkylating drugs. Anticancer Drugs. 1997;8(5):509–16. 10.1097/00001813-199706000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Castellino SM, Friedman HS, Elion GB, et al. : Flunarizine enhancement of melphalan activity against drug-sensitive/resistant rhabdomyosarcoma. Br J Cancer. 1995;71(6):1181–7. 10.1038/bjc.1995.230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Silvestrini R, Zaffaroni N, Costa A, et al. : Flunarizine as a modulator of doxorubicin resistance in human colon-adenocarcinoma cells. Int J Cancer. 1993;55(4):636–9. 10.1002/ijc.2910550420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Kavanagh BD, Coffey BE, Needham D, et al. : The effect of flunarizine on erythrocyte suspension viscosity under conditions of extreme hypoxia, low pH, and lactate treatment. Br J Cancer. 1993;67(4):734–741. 10.1038/bjc.1993.134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Sezzi ML, Zupi G, De Luca G, et al. : Effects of a calcium-antagonist (flunarizine) on the in vitro growth of B16 mouse melanoma cells. Anticancer Res. 1984;4(4–5):229–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. So HS, Kim HJ, Lee JH, et al. : Flunarizine induces Nrf2-mediated transcriptional activation of heme oxygenase-1 in protection of auditory cells from cisplatin. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13(10):1763–1755. 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Kang HJ, YI, Hong YB, et al. : HER2 confers drug resistance of human breast cancer cells through activation of NRF2 by direct interaction. Sci Rep. 2014;4: 7201. 10.1038/srep07201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Sakaguchi M, Kuroda Y, Hirose M: The antiproliferative effect of lidocaine on human tongue cancer cells with inhibition of the activity of epidermal growth factor receptor. Anesth Analg. 2006;102(4):1103–1107. 10.1213/01.ane.0000198330.84341.35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Mammoto T, Higashiyama S, Mukai M, et al. : Infiltration anesthetic lidocaine inhibits cancer cell invasion by modulating ectodomain shedding of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF). J Cell Physiol. 2002;192(3):351–8. 10.1002/jcp.10145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Baptista-Hon DT, Robertson FM, Robertson GB, et al. : Potent inhibition by ropivacaine of metastatic colon cancer SW620 cell invasion and Na V1.5 channel function. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113( Suppl 1):i39–i48. 10.1093/bja/aeu104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Piegeler T, Votta-Velis EG, Liu G, et al. : Antimetastatic potential of amide-linked local anesthetics: inhibition of lung adenocarcinoma cell migration and inflammatory Src signaling independent of sodium channel blockade. Anesthesiology. 2012;117(3):548–559. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182661977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Poulin H, Bruhova I, Timour Q, et al. : Fluoxetine blocks Na v1.5 channels via a mechanism similar to that of class 1 antiarrhythmics. Mol Pharmacol. 2014;86(4):378–89. 10.1124/mol.114.093104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Wang Y, Mi J, Lu K, et al. : Comparison of Gating Properties and Use-Dependent Block of Na v1.5 and Na v1.7 Channels by Anti-Arrhythmics Mexiletine and Lidocaine. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0128653. 10.1371/journal.pone.0128653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Mammoto T, Mukai M, Mammoto A, et al. : Intravenous anesthetic, propofol inhibits invasion of cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2002;184(2):165–70. 10.1016/S0304-3835(02)00210-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Besson P, Driffort V, Bon É, et al. : How do voltage-gated sodium channels enhance migration and invasiveness in cancer cells? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015; pii: S0005-2736(15)00136-4. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Brown MT, Herrmann DN, Goldstein M, et al. : Nerve safety of tanezumab, a nerve growth factor inhibitor for pain treatment. J Neurol Sci. 2014;345(1–2):139–47. 10.1016/j.jns.2014.07.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Kalman D, Wong B, Horvai AE, et al. : Nerve growth factor acts through cAMP-dependent protein kinase to increase the number of sodium channels in PC12 cells. Neuron. 1990;4(3):355–366. 10.1016/0896-6273(90)90048-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Mnich K, Carleton LA, Kavanagh ET, et al. : Nerve growth factor-mediated inhibition of apoptosis post-caspase activation is due to removal of active caspase-3 in a lysosome-dependent manner. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1202. 10.1038/cddis.2014.173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Chioni AM, Brackenbury WJ, Calhoun JD, et al. : A novel adhesion molecule in human breast cancer cells: voltage-gated Na + channel beta1 subunit. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41(5):1216–1227. 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Nelson M, Millican-Slater R, Forrest LC, et al. : The sodium channel β1 subunit mediates outgrowth of neurite-like processes on breast cancer cells and promotes tumour growth and metastasis. Int J Cancer. 2014;135(10):2338–2351. 10.1002/ijc.28890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Brisson L, Gillet L, Calaghan S, et al. : Na V1.5 enhances breast cancer cell invasiveness by increasing NHE1-dependent H + efflux in caveolae. Oncogene. 2011;30(17):2070–2076. 10.1038/onc.2010.574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Stettner M, Krämer G, Strauss A, et al. : Long-term antiepileptic treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors may reduce the risk of prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2012;21(1):55–64. 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e32834a7e6f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]