ABSTRACT

The surface area of the maxilloturbinals and fronto-ethmoturbinals is commonly used as an osteological proxy for the respiratory and the olfactory epithelium, respectively. However, this assumption does not fully account for animals with short snouts in which these two turbinal structures significantly overlap, potentially placing fronto-ethmoturbinals in the path of respiratory airflow. In these species, it is possible that anterior fronto-ethmoturbinals are covered with non-sensory (respiratory) epithelium instead of olfactory epithelium. In this study, we analyzed the distribution of olfactory and non-sensory, respiratory epithelia on the turbinals of two domestic cats (Felis catus) and a bobcat (Lynx rufus). We also conducted a computational fluid dynamics simulation of nasal airflow in the bobcat to explore the relationship between epithelial distribution and airflow patterns. The results showed that a substantial amount of respiratory airflow passes over the anterior fronto-ethmoturbinals, and that contrary to what has been observed in caniform carnivorans, much of the anterior ethmoturbinals are covered by non-sensory epithelium. This confirms that in short-snouted felids, portions of the fronto-ethmoturbinals have been recruited for respiration, and that estimates of olfactory epithelial coverage based purely on fronto-ethmoturbinal surface area will be exaggerated. The correlation between the shape of the anterior fronto-ethmoturbinals and the direction of respiratory airflow suggests that in short-snouted species, CT data alone are useful in assessing airflow patterns and epithelium distribution on the turbinals.

KEY WORDS: Airflow, Ethmoturbinal, Histology, Maxilloturbinal, Respiratory physiology

Summary: Olfactory and non-sensory epithelia in the nose tend to be located in the path of olfactory and respiratory airflow, respectively. Some ethmoturbinals are shown to function in respiration in short-snouted felids.

INTRODUCTION

Mammals vary widely in their reliance on olfaction, ranging from those with very limited or no sense of smell, as is the case in cetaceans (Godfrey et al., 2013), to those with reduced abilities such as semi-aquatic seals or sea lions (Negus, 1958) and visually dominant species (Schreider and Raabe, 1981; Proctor, 1982; Smith et al., 2004, 2007a; Hornung, 2006; Smith and Rossie, 2008), to those with enhanced abilities such as terrestrial caniforms (e.g. canids, ursids) (Pihlström, 2008; Craven et al., 2007; Van Valkenburgh et al., 2011). To understand the evolution of this variation, it is useful to estimate olfactory ability across a wide range of species, both extant and extinct. To do so, investigators have relied on osteological proxies of olfactory ability, such as olfactory bulb size (Healy and Guilford, 1990), ethmoid plate surface area (Bhatnagar and Kallen, 1974; Pihlström et al., 2005; Pihlström, 2008; Bird et al., 2014) or the area of the nasal cavity covered in olfactory epithelium (OE) (Negus, 1958; Wako et al., 1999; Rowe et al., 2005; Van Valkenburgh et al., 2011; Green et al., 2012). The latter is typically estimated from the surface area of the ethmoturbinals and frontoturbinals, a connected set of bony scrolls that are largely housed within the caudal-most aspect of the nasal cavity. This is based on the assumption that the ethmoturbinal and frontoturbinal scrolls are covered in sensory (olfactory) epithelium to the same degree in all species.

However, recent histological studies have shown that while this assumption may hold for species with a long snout, it is not true of short-snouted species, such as small primates, bats and at least one marsupial (Rowe et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2007a,b, 2012). In these species, the first ethmoturbinal (Maier, 1993; Smith and Rossie, 2006) extends far forward in the foreshortened nasal cavity, placing it within the respiratory airflow path, where it is covered in respiratory epithelium rather than OE. Thus, the surface area of the ethmoturbinals is an overestimate of olfactory surface area (and presumably ability) in these species. Similarly, estimates of the surface area available for heat and moisture transfer during respiration based solely on the maxilloturbinals will be underestimated.

In addition to the aforementioned osteological proxies of olfactory ability, recent studies (Craven et al., 2007, 2010; Lawson et al., 2012) have demonstrated that the anatomical structure of the nasal cavity and the resulting intranasal airflow and odorant deposition patterns may also contribute significantly to olfactory ability. Specifically, Craven et al. (2007, 2010) suggested that two key features of the nasal cavity in keen-scented (macrosmatic) animals (including carnivorans) are the presence of a dorsal meatus, which functions as a bypass for airflow around the maxilloturbinals, and a posteriorly located olfactory recess that may be partially or entirely separated from the respiratory airflow path by a thin plate of bone called the transverse lamina (Negus, 1958). As a result of this nasal morphology, airflow in the canine nose was shown to split into distinct respiratory and olfactory flow paths, in which olfactory airflow is directed through the dorsal meatus to the posterior olfactory recess, where it then slowly flows anteriorly through the fronto-ethmoturbinal complex, eventually reaching the nasopharynx and exiting the nasal cavity (Craven et al., 2010). Additionally, Craven et al. (2010) postulated that because macrosmatic animals (e.g. carnivorans, ungulates, rodents and marsupials) all appear to possess a common gross nasal architecture consisting of a dorsal meatus and an olfactory recess, similar nasal airflow patterns might be expected in these species. Nasal airflow studies in the rat support this assertion (Kimbell et al., 1997; Zhao et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2007a). In contrast, airflow patterns in the feeble-scented (microsmatic) human nasal cavity, which lacks a dorsal meatus and an olfactory recess, vary significantly from those in macrosmatic species, largely because the olfactory region in humans is situated within the main respiratory airflow path through the nasal cavity (e.g. see Keyhani et al., 1995; Subramaniam et al., 1998; Zhao et al., 2004, 2006).

Although felids are considered to be macrosmats relative to primates, including humans, they are similar to non-human primates in having reduced snout lengths. An earlier study that estimated respiratory turbinal size in canids and felids, based on maxilloturbinal bone volume, found that felids have reduced maxilloturbinals relative to canids (Van Valkenburgh et al., 2004). By itself, this finding suggests a reduced ability to condition inspired air as well as to retain heat and water relative to canids, but this seems unlikely given that canids and felids share similar environments and have widely overlapping geographic ranges. Instead, it may be that, as in other short-snouted mammals, the anterior ethmoturbinals have been recruited to participate in respiration rather than olfaction. To explore this possibility, we analyzed the distribution of OE versus non-sensory epithelium in the nasal cavity of the domestic cat, Felis catus, using standard histological techniques and compared this with a similar analysis of the bobcat, Lynx rufus (Yee et al., 2016). To better understand the relationship between tissue distribution and cranial anatomy in three dimensions, we matched selected slices from computed tomography (CT) scans of a domestic cat skull to our histological sections, and highlighted regions covered by OE and non-sensory epithelia on the CT scans. We also performed a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation of nasal airflow in the bobcat to assess the correlation between airflow patterns and epithelial distribution on the turbinals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal and tissue collection

For the domestic cat, we sampled two adults, a 10-year-old male with normal genotype and phenotype (cat 4298) and a 6.5-month-old male (cat 6559) heterozygous for a mucopolysaccharidoses VI genotype and normal phenotype. Histological samples were obtained at autopsy from cats housed at the University of Pennsylvania, School of Veterinary Medicine, and euthanized with an overdose (80 mg kg−1) of pentobarbital in accordance with protocols approved by its Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and the guidelines of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Experiments described in this work conformed to the National Institutes of Health guide for the care and use of laboratory animals (NIH Publications 80-23, revised 1978). The anterior portion of each head containing the nose and olfactory bulbs was removed and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 7 days, beginning 15–30 min after euthanasia. After 7 days of fixation, the heads were decalcified in Sorenson's solution [5% ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) in phosphate buffer, pH 6.8], and then cryoprotected in 10%, 20% and 30% sucrose series. The lower jaws and muscles were removed and the noses were frozen in M1 embedding matrix (Shandon Lipshaw, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). A series of coronal sections (16–20 μm) were made at various intervals. Sections were placed onto Superfrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) or Starfrost Adhesive slides (Mercedes Medical, Sarasota, FL, USA) and stored at −80°C.

For the bobcat, a single adult specimen was acquired from a trapper in Pennsylvania in accordance with the regulations of the Pennsylvania Game Commission. The head was removed and the nose was flushed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and was then placed in the same fixative solution for approximately 2 weeks at 4°C. The specimen was then immersed for another 2 weeks in a phosphate-buffered saline solution containing approximately 0.25% Magnevist (Bayer, Germany) for high-resolution magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning. After MRI scanning of the nasal cavity was completed, the specimen was then shipped to the Monell Chemical Senses Center (Philadelphia, PA, USA) for histological analysis. As described in Yee et al. (2016), the head was immersed in a decalcification HCl–EDTA buffer solution (Mercedes Medical) after removing the skin and soft tissues surrounding the nose and skull, and stored at 4°C for 6 weeks, with changes of solution every 3 to 4 days. The nose was then further cleaned by removing the teeth, lower jaw, orbital bones and posterior regions of the skull. The nose was bisected into sagittal halves and the right side was used for histological analysis.

Histological staining

Domestic cat slides were initially dried in an oven at 56°C overnight. After rehydration with dH2O, slides were stained with Alcian Blue at pH 2.5 for 10 min (Fisher Scientific) to label goblet cells and Bowman's glands, rinsed three times with dH2O, followed by Nuclear Fast Red (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA) for 3–4 min. After rinsing three times with dH2O, the slides were dried in an oven for 1 h and cleared with Histoclear (National Diagnostics, Atlanta, GA, USA) and mounted on glass coverslips with Permount (Fisher Scientific). For cat 4298, 65 slides at intervals between 160 and 200 μm were stained. Of those, 26 stained sections, between 0.5 and 2.5 mm apart, were selected for quantitative measurement with the most anterior section at approximately 14 mm posterior to the tip of the nose and the last section at a distance of 43.45 mm from the tip of the nose. For cat 6559, 26 stained slides, between 0.3 and 2.6 mm apart, with similar turbinal anatomy to that in the selected sections from cat 4298, were chosen for staining and quantitative analysis.

For the bobcat, 21 slides at intervals from 200 to 400 μm were stained with Alcian Blue and Nuclear Fast Red. To further visualize OE from non-sensory epithelium, adjacent sections were labeled with β-tubulin III antibody, as has been previously done to label olfactory neurons in cats (Lischka et al., 2008). After washing, tissue sections were incubated with a secondary mouse biotinylated antibody (Vector Laboratories), followed by the avidin-biotinylated horseradish peroxidase complex ABC Elite Kit (Vector Laboratories). Sections were then reacted with the chromogen diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma Chemicals) and 0.1% H2O2 for visualization.

Quantitative measurements of histological sections

For the domestic cats, selected stained sections were digitally scanned at 1200 dpi resolution on an HP flatbed scanner to generate an 8×10 inch printed hard copy of each section. For the bobcat, stained sections were digitally captured with a RT slider SPOT camera (Diagnostic Instruments) attached to a Nikon SMZ-U dissecting microscope. The septum, maxilloturbinal, nasoturbinal and fronto-ethmoturbinals were identified based on location in each section. Non-sensory epithelium (including respiratory, transitional and stratified epithelia) and OE were identified under 40× and 60× objective magnifications by well-defined histological characteristics of olfactory mucosa as contrasted to the adjacent respiratory mucosa (i.e. epithelial thickness, presence or absence of Alcian Blue stained goblet cells and/or Bowman's glands in the underlining lamina propria). For the domestic cats, OE was identified via well-defined histological characteristics (as described). For the bobcat, OE was identified by β-tubulin labeling.

Digital scans of the domestic cats and bobcat were quantitatively measured using the ImageProPlus 6.0 software (MediaCybernetics). The following measures were taken on each section for both sides of the cat noses and the right side of the bobcat nose: (1) the total length (cross-sectional perimeter) of the septum, maxilloturbinals, nasoturbinals and fronto-ethmoturbinals, and (2) the total length (cross-sectional perimeter) of OE lining each of these structures. Our measurement of the fronto-ethmoturbinal complex includes all larger and smaller turbinals of the ethmoid bone (i.e. combined surface area of the ethmoturbinals, interturbinals and frontoturbinals as defined by Maier, 1993; Smith et al., 2007b; Maier and Ruf, 2014). The perimeter of non-sensory epithelium for each section was determined by subtracting OE perimeter from total septal and turbinal perimeters. The surface area of a given section was calculated by multiplying the perimeter of OE for a section by the distance to the next section. The OE surface areas were summed across all sections to give a cumulative measure of OE surface area on the nasoturbinals, septum and fronto-ethmoturbinals. With these measurements, we also calculated the proportion of the surface area of the turbinals and septum that are covered with OE, as well as the relative OE/non-sensory epithelium ratio in the nasal fossa. As the bobcat measurements were taken from the right half of the nose, cumulative measurements from the domestic cats were divided by two to allow for a consistent comparison.

Because the anterior tips of turbinals may have been excluded if they occurred in the interslice intervals (0.2–0.4 mm), we estimated the maximum possible error. This was done by adding the perimeter of OE measured on its first occurrence to the overall sum of OE on the septum, nasoturbinals, fronto-ethmoturbinals and cumulative total OE, and found the percentage difference that arose from this addition. The maximum OE perimeter measurement error that was due to possibly excluding the anterior tips of turbinals and septum because they ended in an interslice interval was, on average, 4.8% for the septum, 12.7% for the nasoturbinals, 0.04% for the ethmoturbinals and 2.1% for the cumulative total OE surface area.

CT and MRI scans

To view the anatomy in three dimensions, high-resolution CT scans of the skull of a domestic cat (Felis catus) were acquired at the University of Texas (UT) High Resolution X-Ray Computed Tomography Facility. The data set comprises 387 scans of the nasal cavity, with a slice thickness of 0.238 mm, and is available by request from the Digimorph library (http://www.digimorph.org/). The scans were first imported into the software program Mimics 14.0 (Materialise Inc.) to view the three-dimensional data set from coronal, sagittal and transverse perspectives, as well as to enhance visualization of the turbinals by increasing the contrast between the bony turbinals and the air. MRI scanning for the bobcat nose was performed on a 7-Tesla horizontal Agilent system at Pennsylvania State University (PSU). Coronal CT and MRI scans were selected where the morphology of the turbinals most closely resembled histological sections at various locations in the nasal fossa (Figs 1–3). This allowed for a comparison of the relative distributions of epithelium at specific locations in the nasal fossa.

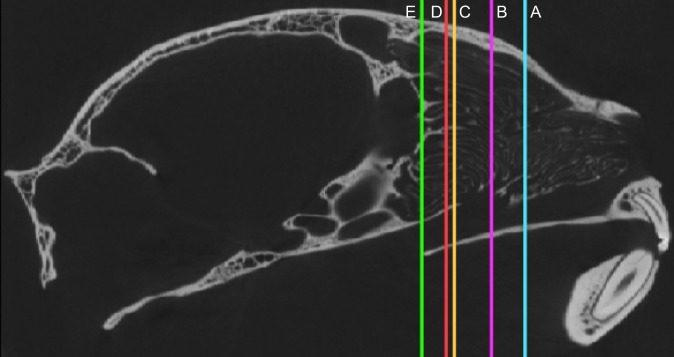

Fig. 1.

Sagittal view of the skull of a domestic cat. Locations A–E are indicated to show the locations of the scans in Fig. 2 within the nasal fossa, and are defined as the percent of the total length of the nasal fossa from anterior to posterior: A, 38%; B, 60%; C, 80%; D, 93%; and E, 98%.

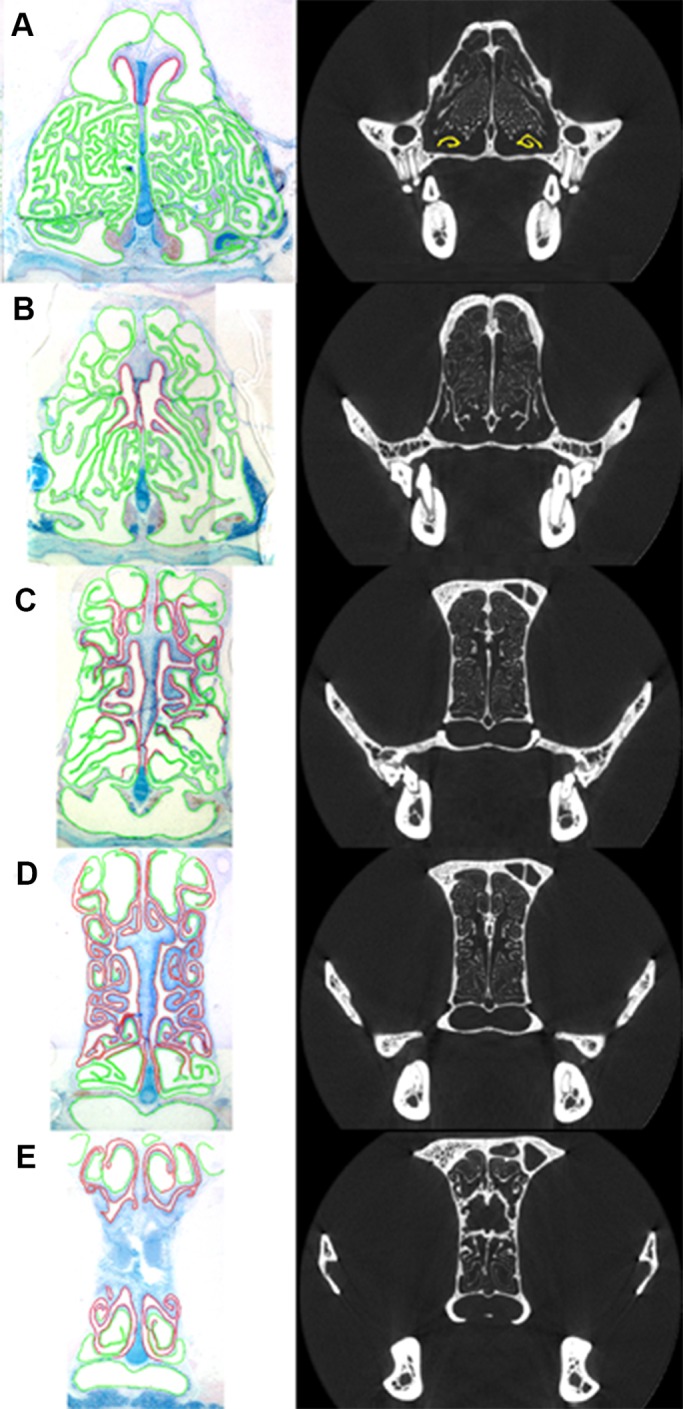

Fig. 3.

Coronal view of histological sections (left) of the turbinals of the bobcat with OE (red) and non-sensory epithelium (green), and coronal MRI scans (right) corresponding to similar locations in the skull. Sections and scans A–E were chosen to approximate those in Fig. 2. In section A, Mt refers to the maxilloturbinals, Ft refers to the fronto-ethmoturbinals and Nt refers to the nasoturbinals. In MRI scan A, the maxilloturbinals have been outlined in yellow.

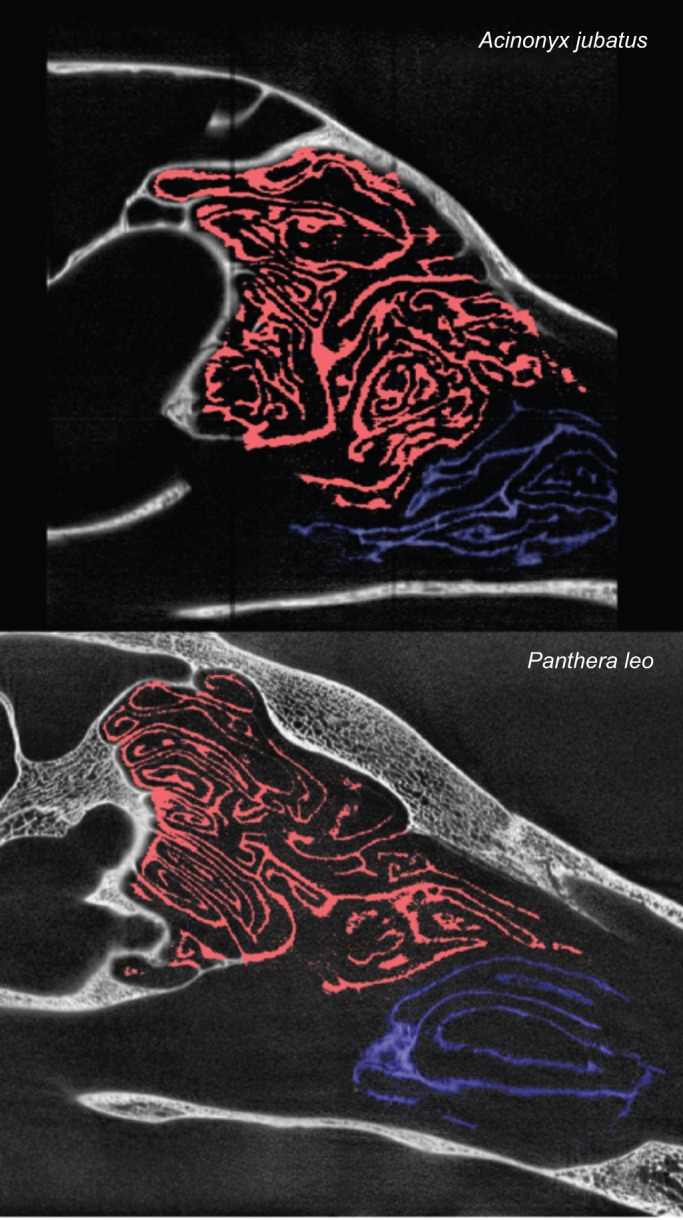

To compare the degree of overlap of the fronto-ethmoturbinals and maxilloturbinals between a long-snouted canid and a short-snouted felid, CT scans of the skull of a Mexican gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi) (USNM 98307, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA) were also obtained from the University of Texas and processed the same way as the scans of the domestic cat. A similar procedure was performed for two additional felids, the cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus, FMNH 29635, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, USA) and the African lion (Panthera leo, MMNH 17537, University of Minnesota Museum of Natural History, Minneapolis, MN, USA). Subsequently, we inspected sagittal scans of the nasal fossa of each animal to estimate the degree of overlap in each case.

Computational fluid dynamics

To examine nasal airflow patterns in a short-snouted felid, we acquired high-resolution (80 μm isotropic) MRI scans (Fig. 4A,B) of the head of the bobcat at PSU and reconstructed a three-dimensional anatomical model of the left nasal airway (Fig. 4C) from the MRI data using the methodology of Craven and colleagues (Craven et al., 2007; Ranslow et al., 2014; Coppola et al., 2014). A high-fidelity, hexahedral-dominant computational mesh (Fig. 4D) was then generated from the reconstructed nasal airway surface model using snappyHexMesh, the unstructured mesh generation utility in the open-source computational continuum mechanics library OpenFOAM (www.openfoam.com). The mesh contained roughly 121 million computational cells, including five wall-normal layers along the airway walls to resolve near-wall velocity gradients and a spherical refinement region around the nostril to resolve the flow as it accelerates toward and enters the naris on inspiration.

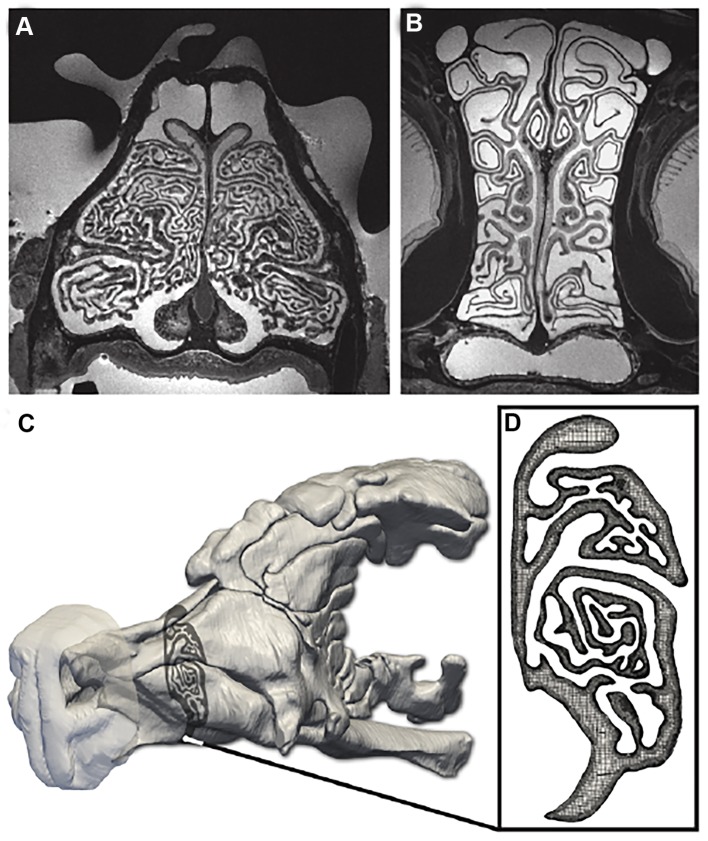

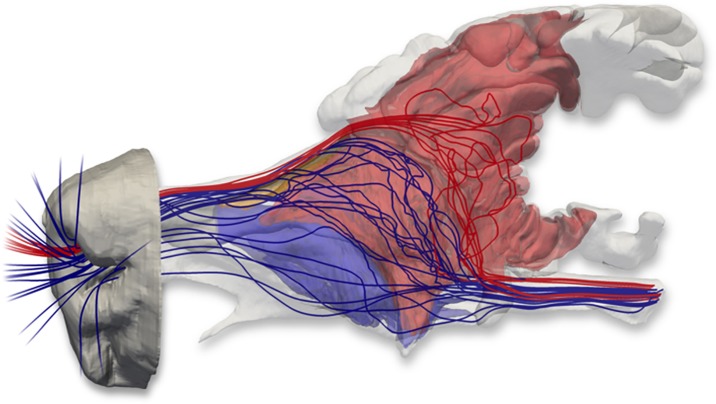

Fig. 4.

Anatomical reconstruction and CFD model of the nasal airway of the bobcat. (A,B) High-resolution (80 μm isotropic) MRI scans of the head of a bobcat cadaver were acquired and used to reconstruct (C) a three-dimensional anatomical model of the left nasal airway. (D) A computational mesh was then generated from the anatomical model and used in a CFD simulation of respiratory airflow in the nose. In the MRI scans (A,B), the airway lumen is light gray, and tissue and bone are dark. In D, the airway is gray.

A steady-state computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulation of laminar airflow during inspiration was performed using OpenFOAM. As in Craven et al. (2009), the computational domain included the anatomical model of the left nasal airway positioned in the center of a large rectangular box with atmospheric pressure boundary conditions assigned to the sides of the box. A pressure outlet boundary condition was specified at the nasopharynx to induce a physiologically realistic respiratory airflow rate of 3.7 l min−1, which was determined from the mass of the specimen (12 kg) and the allometric equation for respiratory minute volume developed by Bide et al. (2000). No-slip boundary conditions were assigned on the external nose and airway walls, which were assumed to be rigid. Additionally, as justified by Craven et al. (2009), the presence of the thin mucus layer that lines the nasal epithelium was neglected.

The SIMPLE (Semi-Implicit Method for Pressure-Linked Equations) algorithm was used to numerically solve the incompressible continuity and Navier–Stokes equations using second-order accurate spatial discretization schemes. The simulation was performed on 480 processors of a parallel computer cluster at PSU. Iterative convergence of the SIMPLE algorithm was obtained by forcing the normalized solution residuals to be less than 10−4. Additionally, the volumetric flow rate, viscous and pressure forces, and other solution quantities were monitored to ensure solution convergence. Visualization and post-processing of the CFD results were performed using the open-source visualization software ParaView (www.paraview.org).

RESULTS

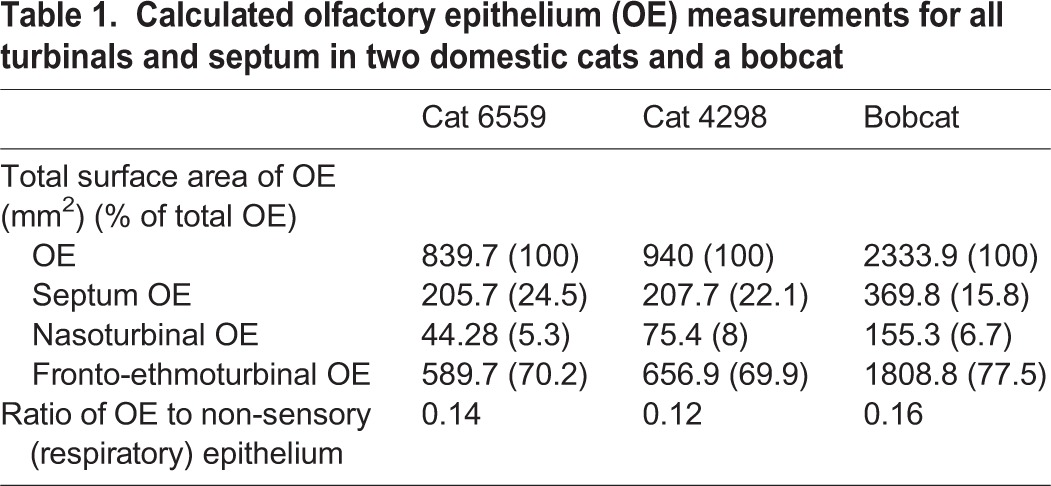

In cat 6559, OE was distributed unequally over the septum, nasoturbinals and fronto-ethmoturbinals. Approximately 24.5% of the total OE could be found on the septum, with the remaining 5.3% and 70.2% lining the nasoturbinals and the fronto-ethmoturbinals, respectively (Table 1). This was similar to the distribution in cat 4298, in which 22.1% of total OE was found on the septum, 8% on the nasoturbinals and 69.9% on the fronto-ethmoturbinals, as well as the bobcat in which 15.8% of total OE was found on the septum, 6.7% on the nasoturbinals and 77.5% on the fronto-ethmoturbinals. On average, cat 6559 had a cumulative total OE surface area of 839.7 mm2, while cat 4298 had a total of 940 mm2. The bobcat had a cumulative total OE surface area of 2333.9 mm2. Overall, the ratio of OE surface area to non-sensory epithelium surface area was 0.14 in cat 6559, 0.12 in cat 4298 and 0.16 in the bobcat.

Table 1.

Calculated olfactory epithelium (OE) measurements for all turbinals and septum in two domestic cats and a bobcat

In both domestic cats, the general pattern of OE distribution in the nasal fossa was similar, and so here we report the results obtained from cat 6559. In the rostral region, the fronto-ethmoturbinals extended anteriorly in the snout, lying above much of the maxilloturbinal complex (Fig. 1A). However, the most anterior appearance of OE was not on the fronto-ethmoturbinals. Instead, it first appeared on the roof of the nasal cavity and the dorsal arch of the nasoturbinals, at a distance of approximately 38% of the total length of the nasal fossa (Fig. 2A). At this location, the maxilloturbinals were barely present. Here, the fronto-ethmoturbinals occupied much of the available space, and were totally covered with non-sensory epithelium.

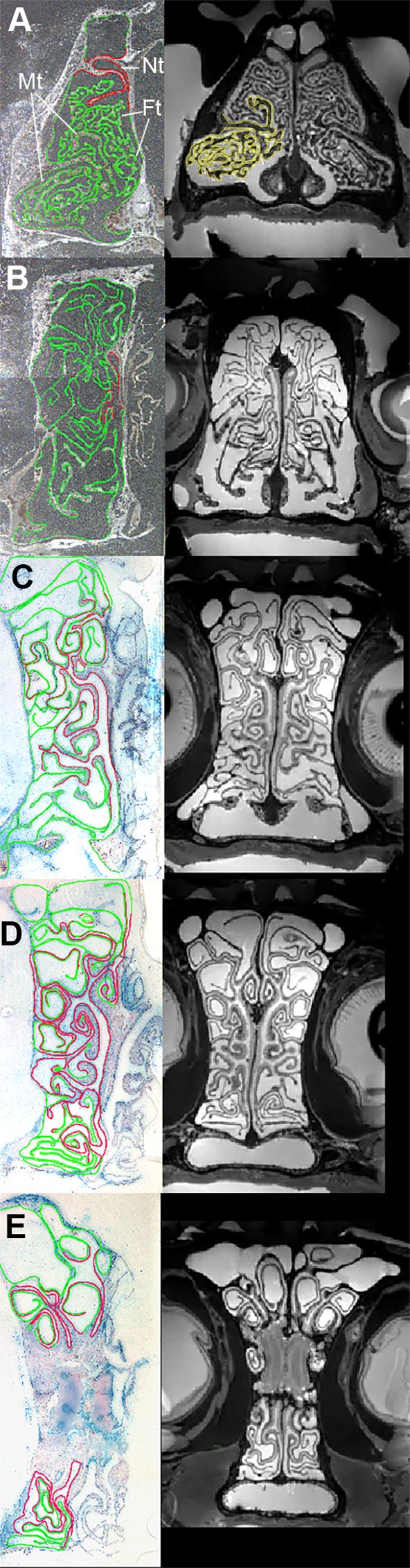

Fig. 2.

Coronal view of histological sections (left) of the turbinals of cat 6559 with olfactory epithelium (OE; red) and non-sensory epithelium (green), and coronal CT scans (right) corresponding to approximately similar locations in the skull. CT scan A has the maxilloturbinals colored in yellow, showing minimal maxilloturbinal presence at this location. See Fig. 1 for location of scans A–E within the skull.

OE remained concentrated on the septum and the medial aspect of the nasoturbinals for the anterior 60% of the total length of the nasal fossa, at which point it began to gradually expand laterally (Fig. 2B). OE was present posterior to the internal nares within the anterior regions of the olfactory recess, where it was predominantly distributed on the septum, nasoturbinals and the medial portion of the fronto-ethmoturbinals (Fig. 2C).

Within the caudal regions of the olfactory recess, the proportional coverage of OE increased posteriorly until, at a position of approximately 90% of the total length of the nasal fossa, 48.6% of the available turbinal and septum surface area was covered by OE (Fig. 2D). At location E, at a position of approximately 98% of the total length of the nasal fossa, OE covered 44.5% of the available surface area, and was split nearly evenly dorsal and ventral to the cribriform plate (Fig. 2E).

In the bobcat, the broad patterns of epithelial distribution (OE and non-sensory) are fairly similar to that of the domestic cat; Fig. 3 shows histological outlines and MRI scans of the bobcat nasal cavity at corresponding locations to that of the domestic cat shown in Fig. 2. In the anterior nasal cavity of the bobcat (Fig. 3A), the fronto-ethmoturbinals are present and are covered with non-sensory epithelium much like in the domestic cat. OE is also first seen in the bobcat covering the nasoturbinals and the roof of the nasal cavity. Subsequently, OE is found on the septum and nasoturbinals (Fig. 3B), and only in the olfactory recess (Fig. 3C–E) does OE occupy a sizeable portion of the available turbinal surface area, which is again comparable to that observed in the domestic cat.

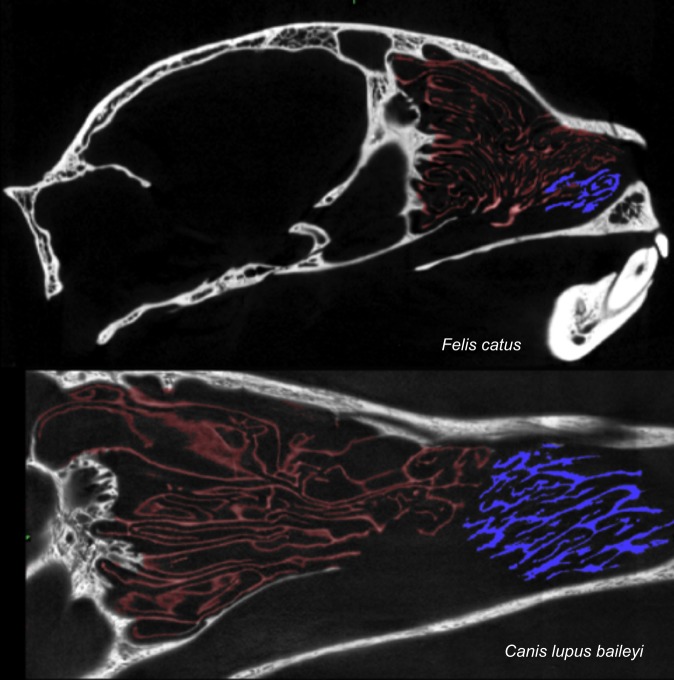

Morphologically, the fronto-ethmoturbinals of the domestic cat extended far forward in the snout and lay above much of the maxilloturbinal complex (Fig. 1A). Compared with the scanned gray wolf, there was much greater overlap of the maxilloturbinal complex and the fronto-ethmoturbinals in the cat (Fig. 5). Indeed, in sagittal sections it appears that the anterior fronto-ethmoturbinals are aligned with the path of respiratory airflow from the external nares to the nasopharynx, as are the maxilloturbinals. The anterior fronto-ethmoturbinals slope downward posteriorly, appearing to be angled towards the internal nares (Fig. 5). This differs from the alignment of more posterior ethmoturbinals, which are roughly horizontal, particularly in the olfactory recess. A comparison between the relatively long-snouted lion and short-snouted cheetah (Fig. 6) showed a similar result: there was substantially greater overlap of the fronto-ethmoturbinals and maxilloturbinals in the cheetah than in the lion, and the anterior fronto-ethmoturbinals also seem to be aligned with the respiratory airflow path.

Fig. 5.

Sagittal CT scans of the turbinals of a domestic cat (Felis catus) and a Mexican gray wolf (Canis lupus baileyi). Ethmoturbinals are in red, maxilloturbinals in blue.

Fig. 6.

Sagittal CT scans of the turbinals of a cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus) and a lion (Panthera leo). Ethmoturbinals are in red, maxilloturbinals in blue.

The CFD simulation of nasal airflow in the bobcat showed that during inspiration, olfactory and respiratory flow paths in the nose are separated; the olfactory flow path passes through the dorsal meatus, directly into the olfactory recess, and subsequently leaves the nasal cavity through the internal nares (Fig. 7). Respiratory airflow, however, does not enter the olfactory recess, but instead flows directly to the internal nares after passing over both the maxilloturbinals and the anterior fronto-ethmoturbinals. Of the two, the anterior fronto-ethmoturbinals comprise a much larger portion of the total respiratory surface area compared with the maxilloturbinals.

Fig. 7.

Nasal airflow patterns in the bobcat obtained from a CFD simulation of airflow in the nose. The fronto-ethmoturbinals (red) and maxilloturbinals (blue) were segmented from the MRI data and are visualized with flow streamlines extracted from the CFD solution. As Craven et al. (2010) found in the domestic dog, separate respiratory and olfactory airflow paths exist in the nasal cavity of the bobcat. Olfactory airflow (illustrated by red streamlines) reaches the olfactory recess via the dorsal meatus, bypassing the convoluted maxilloturbinals. Respiratory airflow (illustrated by blue streamlines) is directed away from the olfactory recess and toward the internal nares by the maxilloturbinals and the anterior extensions of the fronto-ethmoturbinals.

DISCUSSION

In general, cats are regarded as macrosmatic animals, though they are thought to have a weaker sense of smell than dogs, based on their behavior and a comparison of the number of functional olfactory receptor genes in both species (Hayden et al., 2010). Cats are carnivorans, and as such, possess a macrosmatic nasal airway architecture consisting of a dorsal meatus and an olfactory recess (Figs 1, 2). In this study, we found that this nasal architecture results in a general similarity in the nasal airflow patterns between the bobcat and dog, in that olfactory and respiratory airstreams are separated (see Fig. 7 herein and fig. 7 in Craven et al., 2010). However, unlike the dog, anterior extensions of the fronto-ethmoturbinals spatially overlap the maxilloturbinals in both felids (cat and bobcat) and are covered with respiratory epithelium (Fig. 2A,B, 3A). In this region, OE is primarily confined to the dorsal meatus, which contains the olfactory airflow stream, while respiratory airflow passes over the (limited) maxilloturbinals and the anterior fronto-ethmoturbinals, where OE is absent. Thus, the histological distribution of epithelia in the bobcat nose appears to be highly correlated with the nasal airflow patterns. That is, the respiratory airflow stream passes mainly over non-sensory epithelium, whereas OE is primarily exposed to only the olfactory airflow stream (see Figs 3, 7).

Gross nasal morphology and turbinal anatomy in the domestic cat are very similar to that in the bobcat (Figs 2, 3), which strongly suggests that similar nasal airflow patterns occur in the domestic cat. Given the similar epithelial distribution in the domestic cat and bobcat, the correlation between nasal histology and airflow patterns found in the bobcat also likely applies to domestic cats. Accordingly, these data strongly suggest that the anterior fronto-ethmoturbinals have been co-opted for respiratory function in these two species, and likely other similarly short-snouted felids.

The degree of spatial overlap of the fronto-ethmoturbinals and maxilloturbinals in all three short-snouted felids (domestic cat, bobcat and cheetah) was similar and much less than that observed in both the longer-snouted lion and the long-snouted gray wolf. This suggests that the degree of spatial overlap of the fronto-ethmoturbinals and maxilloturbinals is more closely correlated with relative snout length than with phylogenetic groupings such as feliforms versus caniforms.

Given the similarity of the gross nasal architecture and the overall nasal airflow patterns between the dog and the bobcat, we might also expect qualitatively similar odorant deposition patterns in the olfactory region. Lawson et al. (2012) observed that the highest odorant deposition fluxes are located anteriorly in the sensory region of the canine nose, along the dorsal meatus and nasal septum, which is consistent with our observation of OE being concentrated in this location in the domestic cat (Fig. 2) and bobcat (Fig. 3). In the canine, highly soluble odorants are deposited anteriorly in the sensory region, particularly along the dorsal meatus, and less-soluble odorants are deposited more uniformly (Lawson et al., 2012). OE in the cats is concentrated on the medial aspect of the olfactory recess, with less OE being distributed peripherally; hence, there is less surface area for detecting moderately soluble and insoluble odorants. Accordingly, compared with other animals that possess more peripheral OE, cats may have a reduced sense of smell for less-soluble odorants.

Compared with other species, it is interesting to note that Smith et al. (2007a,b) also observed respiratory mucosa on fronto-ethmoturbinal I in the mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus) and noted that it is positioned more anteriorly and is, therefore, exposed to respiratory airflow (Smith et al., 2007b). Thus, it appears that fronto-ethmoturbinals in the mouse lemur also may have been co-opted for respiratory air-conditioning. This suggests that fronto-ethmoturbinals that function in respiration may have arisen convergently in primates and carnivorans as a result of having a shorter snout, either through selection for enhanced jaw muscle leverage in feliforms (Biknevicius and Van Valkenburgh, 1996) or other selection factors that led to reduced primate snouts (Smith et al., 2007b).

In our study of feliform and caniform carnivorans, there appears to be a clear relationship between turbinal architecture, nasal airflow and epithelial distribution. Recent research has shown that airflow may influence turbinal size and shape during development (Coppola et al., 2014), which is consistent with the results of the present study. Inferring epithelial surface area from CT data alone is difficult, but can be improved by taking into account nasal airflow patterns and the variability of OE distribution in different species. In this study, we have shown that visual inspection of CT data can offer an initial insight into expected nasal airflow patterns and epithelial distribution. Future work will focus on documenting OE distribution in more short-snouted taxa and testing our hypotheses concerning nasal airflow and odorant deposition patterns using CFD (e.g. as in Zhao et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2007a,b; Craven et al., 2009, 2010; Lawson et al., 2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to T. Ryan and T. Neuberger at PSU for providing CT scans of the domestic cat and MRI scans of the bobcat, respectively. We thank C. Packer for the loan of the African lion skull, as well as the curatorial staff of the US National Museum and the Field Museum of Natural History for the loans of the gray wolf and cheetah skulls, respectively. We thank A. Quigley, A. Ranslow and A. Rygg for assistance in segmenting and reconstructing the MRI data of the bobcat. We also thank L. Lo for assistance in staining and measuring cat sections and anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript. Histology was performed at the Monell Histology and Cellular Localization Core.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

B.P. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. K.K.Y. performed histological work, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. F.W.L. performed histological work on the domestic cat specimens and reviewed the manuscript. N.E.R. contributed to the development of the initial hypotheses, experimental planning and methods, and assisted with editing of the manuscript. M.E.H. provided the cat samples and reviewed the manuscript. C.J.W. was principal investigator on NSF Award 1118852 and provided intellectual and editorial input. B.A.C. was principal investigator on NSF Award 1120375, performed the CFD simulations and wrote the manuscript. B.V.V. was principal investigator on NSF Awards 0517748 and 1119768, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

Histology was supported, in part, by funding from the National Institutes of Health–National Institute on Deafness and other Communication Disorders Core Grant P30DC011735. The study was also supported by the National Science Foundation [IOS-0517748 and IOS-1119768 to B.V.V., IOS-1118852 to C.J.W. and IOS-1120375 to B.A.C.] and the National Institutes of Health [P40-OD010939 to M.E.H.]. Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Data availability

The domestic cat CT scan data set is available by request from the Digimorph library (http://www.digimorph.org/).

References

- Bhatnagar K. P. and Kallen F. C. (1974). Cribriform plate of ethmoid, olfactory bulb and olfactory acuity in forty species of bats. J. Morphol. 142, 71-89. 10.1002/jmor.1051420104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bide R. W., Armour S. J. and Yee E. (2000). Allometric respiration/body mass data for animals to be used for estimates of inhalation toxicity to young adult humans. J. Appl. Toxicol. 20, 273-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biknevicius A. R. and Van Valkenburgh B. (1996). Design for killing: craniodental adaptations of predators. In Carnivore Behavior, Ecology, and Evolution, Vol. 2 (ed. Gittleman J. L.), pp. 393-428. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bird D. J., Amirkhanian A., Pang B. and Van Valkenburgh B. (2014). Quantifying the cribriform plate: influences of allometry, function, and phylogeny in Carnivora. Anat. Rec. 297, 2080-2092. 10.1002/ar.23032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola D. M., Craven B. A., Seeger J. and Weiler E. (2014). The effects of naris occlusion on mouse nasal turbinate development. J. Exp. Biol. 217, 2044-2052. 10.1242/jeb.092940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven B. A., Neuberger T., Paterson E. G., Webb A. G., Josephson E. M., Morrison E. E. and Settles G. S. (2007). Reconstruction and morphometric analysis of the nasal airway of the dog (Canis familiaris) and implications regarding olfactory airflow. Anat. Rec. 290, 1325-1340. 10.1002/ar.20592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven B. A., Paterson E. G., Settles G. S. and Lawson M. J. (2009). Development and verification of a high-fidelity computational fluid dynamics model of canine nasal airflow. J. Biomech. Eng. 131, 091002 10.1115/1.3148202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craven B. A., Paterson E. G. and Settles G. S. (2010). The fluid dynamics of canine olfaction: unique nasal airflow patterns as an explanation of macrosmia. J. R. Soc. Interface 7, 933-943. 10.1098/rsif.2009.0490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey S. J., Geisler J. and Fitzgerald E. M. G. (2013). On the olfactory anatomy in an archaic whale (Protocetidae, Cetacea) and the minke whale Balaenoptera acutorostrata (Balaenopteridae, Cetacea). Anat. Rec. 296, 257-272. 10.1002/ar.22637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green P. A., Van Valkenburgh B., Pang B., Bird D., Rowe T. and Curtis A. (2012). Respiratory and olfactory turbinal size in canid and arctoid carnivorans. J. Anat. 221, 609-621. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2012.01570.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden S., Bekaert M., Crider T. A., Mariani S., Murphy W. J. and Teeling E. C. (2010). Ecological adaptation determines functional mammalian olfactory subgenomes. Genome Res. 20, 1-9. 10.1101/gr.099416.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy S. and Guilford T. (1990). Olfactory-bulb size and nocturnality in birds. Evolution 44, 339-346. 10.2307/2409412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung D. E. (2006). Nasal anatomy and the sense of smell. Adv. Otorhinolaryngol. 63, 1-22. 10.1159/000093747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyhani K., Scherer P. W. and Mozell M. M. (1995). Numerical simulation of airflow in the human nasal cavity. J. Biomech. Eng. 117, 429-441. 10.1115/1.2794204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimbell J. S., Godo M. N., Gross E. A., Joyner D. R., Richardson R. B. and Morgan K. T. (1997). Computer simulation of inspiratory airflow in all regions of the F344 rat nasal passages. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 145, 388-398. 10.1006/taap.1997.8206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson M. J., Craven B. A., Paterson E. G. and Settles G. S. (2012). A computational study of odorant transport and deposition in the canine nasal cavity: implications for olfaction. Chem. Senses 37, 553-566. 10.1093/chemse/bjs039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lischka F. W., Gomez G., Yee K. K., Dankulich-Nagrundy L., Lo L., Haskins M. E. and Rawson N. E. (2008). Altered olfactory epithelial structure and function in feline models of mucopolysaccharidoses I and VI. J. Comp. Neurol. 511, 360-372. 10.1002/cne.21847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier W. (1993). Zur evolutiven und funktionellen Morphologie des Gesichtsschädels der Primaten. Z. Morphol. Anthropol. 79, 279-299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier W. and Ruf I. (2014). Morphology of the nasal capsule of primates-with special reference to Daubentonia and Homo. Anat. Rec. 297, 1985-2006. 10.1002/ar.23023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Negus V. (1958). The Comparative Anatomy and Physiology of the Nose and Paranasal Sinuses. Edinburgh: E. & S. Livingstone. [Google Scholar]

- Pihlström H. (2008). Comparative anatomy and physiology of chemical senses in aquatic mammals. In Sensory Evolution on the Threshold (ed. Thewissen J. G. M. and Nummela S.), pp. 95-109. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pihlström H., Fortelius M., Hemilä S., Forsman R. and Reuter T. (2005). Scaling of mammalian ethmoid bones can predict olfactory organ size and performance. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 272, 957-962. 10.1098/rspb.2004.2993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor D. F. (1982). The upper airway. In The Nose: Upper Airway Physiology and the Atmospheric Environment (ed. Proctor D. F.. and Andersen I. H. P.), pp. 23-43. New York, NY: Elsevier Biomedical Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ranslow A. N., Richter J. P., Neuberger T., Van Valkenburgh B., Rumple C. R., Quigley A. P., Pang B., Krane M. H. and Craven B. A. (2014). Reconstruction and morphometric analysis of the nasal airway of the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) and implications regarding respiratory and olfactory airflow. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 297, 2138-2147. 10.1002/ar.23037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe T. B., Eiting T. P., Macrini T. E. and Ketcham R. A. (2005). Organization of the olfactory and respiratory skeleton in the nose of the gray short-tailed opossum Monodelphis domestica. J. Mamm. Evol. 12, 303-336. 10.1007/s10914-005-5731-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schreider J. P. and Raabe O. G. (1981). Anatomy of the nasal-pharyngeal airway of experimental animals. Anat. Rec. 200, 195-205. 10.1002/ar.1092000208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. D. and Rossie J. B. (2006). Primate olfaction: anatomy and evolution. In Olfaction and the Brain: Window to the Mind (ed. Brewer W., Castle D., and Pantelis C.), pp. 135-166. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. D. and Rossie J. B. (2008). Nasal fossa of mouse and dwarf lemurs (Primates, Cheirogaleidae). Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 291, 895-915. 10.1002/ar.20724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. D., Bhatnagar K. P., Tuladhar P. and Burrows A. M. (2004). Distribution of olfactory epithelium in the primate nasal cavity: are microsmia and macrosmia valid morphological concepts? Anat. Rec. A Discov. Mol. Cell. Evol. Biol. 281A, 1173-1181. 10.1002/ar.a.20122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. D., Bhatnagar K. P., Rossie J. B., Docherty B. A., Burrows A. M., Cooper G. M., Mooney M. P. and Siegel M. I. (2007a). Scaling of the first ethmoturbinal in nocturnal strepsirrhines: olfactory and respiratory surfaces. Anat. Rec. 290, 215-237. 10.1002/ar.20428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. D., Rossie J. B. and Bhatnagar K. P. (2007b). Evolution of the nose and nasal skeleton in primates. Evol. Anthropol. 16, 132-146. 10.1002/evan.20143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. D., Eiting T. P. and Bhatnagar K. P. (2012). A quantitative study of olfactory, non-olfactory, and vomeronasal epithelia in the nasal fossa of the bat Megaderma lyra. J. Mamm. Evol. 19, 27-41. 10.1007/s10914-011-9178-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam R. P., Richardson R. B., Morgan K. T. and Kimbell J. S. (1998). Computational fluid dynamics simulations of inspiratory airflow in the human nose and nasopharynx. Inhal. Toxicol. 10, 91-120. 10.1080/089583798197772 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Valkenburgh B., Theodor J., Friscia A., Pollack A. and Rowe T. (2004). Respiratory turbinates of canids and felids: a quantitative comparison. J. Zool. 264, 281-293. 10.1017/S0952836904005771 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Valkenburgh B., Curtis A., Samuels J. X., Bird D., Fulkerson B., Meachen-Samuels J. and Slater G. J. (2011). Aquatic adaptations in the nose of carnivorans: evidence from the turbinates. J. Anat. 218, 298-310. 10.1111/j.1469-7580.2010.01329.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wako K., Hiratsuka H., Katsuta O. and Tsuchitani M. (1999). Anatomical structure and surface epithelial distribution in the nasal cavity of the common cotton-eared marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). Exp. Anim. 48, 31-36. 10.1538/expanim.48.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G. C., Scherer P. W. and Mozell M. M. (2007a). Modeling inspiratory and expiratory steady-state velocity fields in the Sprague-Dawley rat nasal cavity. Chem. Senses 32, 215-223. 10.1093/chemse/bjl047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang G. C., Scherer P. W., Zhao K. and Mozell M. M. (2007b). Numerical modeling of odorant uptake in the rat nasal cavity. Chem. Senses 32, 273-284. 10.1093/chemse/bjl056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee K. K., Craven B. A., Wysocki C. J. and Van Valkenburgh B. (2016). Comparative morphology and histology of the nasal fossa in four mammals: gray squirrel, bobcat, coyote and white-tailed deer. Anat. Rec. (in press). 10.1002/ar.23352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K., Scherer P. W., Hajiloo S. A. and Dalton P. (2004). Effect of anatomy on human nasal air flow and odorant transport patterns: implications for olfaction. Chem. Senses 29, 365-379. 10.1093/chemse/bjh033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao K., Dalton P., Yang G. C. and Scherer P. W. (2006). Numerical modeling of turbulent and laminar airflow and odorant transport during sniffing in the human and rat nose. Chem. Senses 31, 107-118. 10.1093/chemse/bjj008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]