Abstract

Cationic liposomes (CLs) are synthetic carriers of nucleic acids in gene delivery and gene silencing therapeutics. The introduction will describe the structures of distinct liquid crystalline phases of CL–nucleic acid complexes, which were revealed in earlier synchrotron small-angle X-ray scattering experiments. When mixed with plasmid DNA, CLs containing lipids with distinct shapes spontaneously undergo topological transitions into self-assembled lamellar, inverse hexagonal, and hexagonal CL–DNA phases. CLs containing cubic phase lipids are observed to readily mix with short interfering RNA (siRNA) molecules creating double gyroid CL–siRNA phases for gene silencing. Custom synthesis of multivalent lipids and a range of novel polyethylene glycol (PEG)-lipids with attached targeting ligands and hydrolysable moieties have led to functionalized equilibrium nanoparticles (NPs) optimized for cell targeting, uptake or endosomal escape. Very recent experiments are described with surface-functionalized PEGylated CL–DNA NPs, including fluorescence microscopy colocalization with members of the Rab family of GTPases, which directly reveal interactions with cell membranes and NP pathways. In vitro optimization of CL–DNA and CL–siRNA NPs with relevant primary cancer cells is expected to impact nucleic acid therapeutics in vivo.

This article is part of the themed issue ‘Soft interfacial materials: from fundamentals to formulation’.

Keywords: cationic liposomes, PEGylated nanoparticles, Rab GTPases, gene therapy, small-angle X-ray scattering, fluorescence optical imaging

1. Introduction

Gene therapy has the potential to treat a broad range of diseases that result from missing or defective genes. Engineered viral vectors and synthetic vectors are two distinct types of vectors, requiring different strategies for optimization, that are used in human clinical gene therapy trials targeting both traditional single gene diseases (e.g. cystic fibrosis) and complex multi-gene diseases such as cancer [1]. Cationic liposomes (CLs, closed spherical assemblies of lipids) are the most prevalent synthetic vector [2–15]. Gene delivery using cationic lipid-based vectors, termed lipofection, suffers from low transfection efficiency (TE; the ability to transfer DNA into cells followed by expression) in vivo in comparison with engineered viral vectors but also has advantages. One advantage is safety: to date, uses of adenoviral and retroviral vectors have, respectively, resulted in severe immune reactions with two patient deaths and insertional mutagenesis leading to cancer in two patients treated for X-linked SCID (severe combined immunodeficiency) in a small trial [16–18]. A second advantage is that synthetic vectors have the ability to deliver very large pieces of DNA; indeed, the first artificial human chromosomes (of order 108 bp) were delivered by lipofection [19]. Engineered viruses are limited in their DNA carrying capacity by their capsid size, and to date only cDNA therapeutic genes have been delivered. By contrast, synthetic vectors may carry full-length genes and regulatory sequences.

Cationic liposomes have also been shown to complex with and deliver small interfering RNA (siRNA) [20,21], double-stranded (typically between 19 and 25 bp) RNA molecules with two nucleotide overhangs at the 3′ ends that use the downstream elements of the RNAi pathway to affect sequence-specific gene silencing. The discovery of the RNAi pathway has already been a breakthrough for functional genomics [22,23], and it holds great promise in medicine [24–26]. Cationic liposomes remain one of the most common vectors for the delivery of siRNA [7]. However, while non-viral gene therapy has much potential for clinical use, it has yet to make a significant clinical impact due to the difficulty of designing efficient, programmable delivery vectors for in vivo applications.

2. Self-assembled structures of cationic liposome–nucleic acid complexes determined by synchrotron X-ray scattering

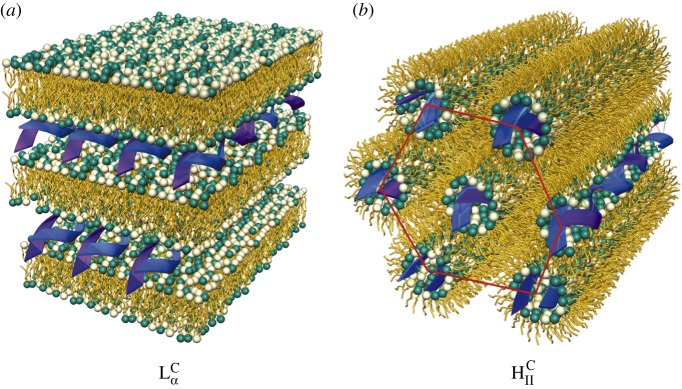

The most prevalent self-assembled structure of CL–DNA complexes was first solved using modern synchrotron-based high-resolution X-ray scattering [27–30]. These studies revealed that when CLs are mixed with DNA, the entropic gain of counter-ion release drives the spontaneous assembly of ‘loosely organized liposomes and DNA’ into highly organized CL–DNA complexes with well-defined liquid crystalline nanostructures. The same work further demonstrated that the particular shape of the lipid molecules constituting the cationic membranes can drive complexes to self-assemble into either a lamellar  phase consisting of alternating lipid bilayers and DNA monolayers or an inverse hexagonal HCII phase with DNA chains inserted in inverse cylindrical micelles arranged on a two-dimensional hexagonal array (figure 1). In these initial experiments, the lamellar phase membranes consisted of a mixture of a neutral zwitterionic lipid (DOPC: 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerophosphatidylcholine) and a univalent cationic lipid (DOTAP: 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane), where both lipids have a cylindrical shape that favours the

phase consisting of alternating lipid bilayers and DNA monolayers or an inverse hexagonal HCII phase with DNA chains inserted in inverse cylindrical micelles arranged on a two-dimensional hexagonal array (figure 1). In these initial experiments, the lamellar phase membranes consisted of a mixture of a neutral zwitterionic lipid (DOPC: 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerophosphatidylcholine) and a univalent cationic lipid (DOTAP: 1,2-dioleoyl-3-trimethylammonium-propane), where both lipids have a cylindrical shape that favours the  phase. The membranes of the inverse hexagonal phase consisted of a neutral zwitterionic lipid (DOPE: 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerophosphatidylethanolamine) with an inverse cone shape (i.e. with lipid headgroup area smaller than lipid tail area) mixed with DOTAP. Later structure–function studies with a series of custom-synthesized multivalent lipids [31–33] showed that these two phases of CL–DNA complexes had significantly different transfection properties. TE for lamellar

phase. The membranes of the inverse hexagonal phase consisted of a neutral zwitterionic lipid (DOPE: 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycerophosphatidylethanolamine) with an inverse cone shape (i.e. with lipid headgroup area smaller than lipid tail area) mixed with DOTAP. Later structure–function studies with a series of custom-synthesized multivalent lipids [31–33] showed that these two phases of CL–DNA complexes had significantly different transfection properties. TE for lamellar  complexes falls on a universal bell-shaped curve when plotted as a function of the membrane charge density (σM) of the complex [33,34]. For the non-lamellar HCII phase, TE is typically high and independent of σM [33].

complexes falls on a universal bell-shaped curve when plotted as a function of the membrane charge density (σM) of the complex [33,34]. For the non-lamellar HCII phase, TE is typically high and independent of σM [33].

Figure 1.

Two self-assembled liquid crystalline structures of cationic liposomes (CLs) mixed with DNA at equilibrium. The nanometre-scale structures were solved by synchrotron X-ray diffraction studies. (a) The lamellar  phase of CL–DNA complexes with alternating lipid bilayers and DNA monolayers. (b) The inverted hexagonal HCII phase of CL–DNA complexes, composed of DNA inserted within inverse lipid tubules which are arranged on a hexagonal lattice. Adapted with permission from AAAS from [27] and [28].

phase of CL–DNA complexes with alternating lipid bilayers and DNA monolayers. (b) The inverted hexagonal HCII phase of CL–DNA complexes, composed of DNA inserted within inverse lipid tubules which are arranged on a hexagonal lattice. Adapted with permission from AAAS from [27] and [28].

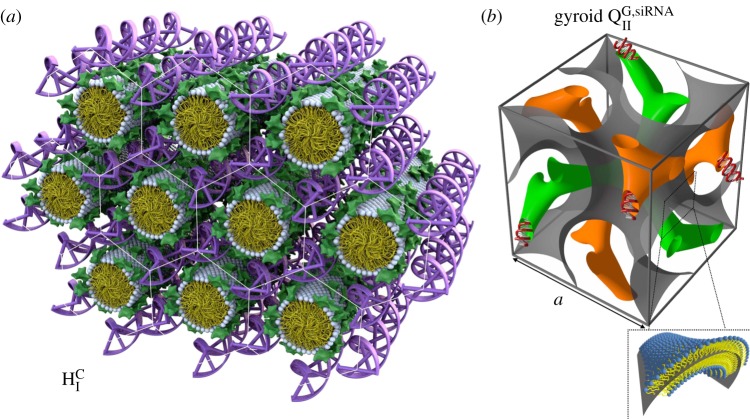

The formation of a new CL–DNA HCI phase with hexagonally ordered DNA rods surrounded by cylindrical micelles (figure 2a) was first reported after the successful custom synthesis of a novel multivalent cone-shaped lipid, MVLBG2, containing an unusually large dendritic head group with charge +16e [35]. Remarkably, this structure was found to improve TE in hard-to-transfect mouse embryonic fibroblast cells. More recently, a novel bicontinuous gyroid cubic phase (figure 2b, labelled QG,siRNAII) with siRNA incorporated within its two water channels was reported [36–38]. This phase was discovered in mixtures of siRNA with CLs containing a cubic phase forming lipid (GMO: 1-monooleoyl-glycerol) and DOTAP or the multivalent cationic lipid MVL5. The gyroid QG,siRNAII phase shows high silencing efficiency due to the tendency of cubic phase-forming lipids to induce pores in the endosomal membranes that envelop CL–siRNA complexes and thus facilitate cytoplasmic delivery [36]. Significantly, DOTAP/GMO–siRNA complexes in the gyroid cubic QG,siRNAII phase, at low cationic lipid content (i.e. low σM), show remarkably improved sequence-specific gene silencing compared with lamellar  phase complexes with the same σM.

phase complexes with the same σM.

Figure 2.

The structure of the hexagonal phase cationic liposome–DNA (CL–DNA) complexes and of the gyroid cubic phase of CL–siRNA complexes as deduced from synchrotron X-ray scattering. (a) The hexagonal HCI phase of MVLBG2/DOPC–DNA complexes. Multivalent lipid MVLBG2 (+16e) has a large dendritic headgroup, which promotes the formation of rod-like lipid micelles arranged on a hexagonal lattice with DNA inserted within the interstices with honeycomb symmetry. (b) The unit cell of the double-gyroid cubic phase with space group Ia3d. In this phase (labelled QG,siRNAII), siRNA is contained within two water channels (green and orange). For DOTAP/GMO–siRNA complexes the QG,siRNAII phase is observed for GMO molar fractions between 0.75 and 0.975. A lipid bilayer surface separates the two intertwined but independent water channels. The bilayer is represented by a surface (grey) marking the centre of the membrane as indicated in the enlarged inset. (a) Adapted and reprinted with permission from [35]. Copyright © 2006 American Chemical Society. (b) Adapted with permission from [36]. Copyright © 2010 American Chemical Society.

With regard to CLs as carriers of nucleic acids, we are now at a point where we have a comprehensive understanding of the biophysical and functional (TE) properties of CL–nucleic acid complexes, in particular, in our ability to predict how the self-assembled structures and the physico-chemical parameters (e.g. membrane charge density) of the complex influence TE [5,8,10,39].

3. Surface functionalized CL–DNA complexes: PEGylated CL–DNA nanoparticles with and without attached ligand for cell targeting

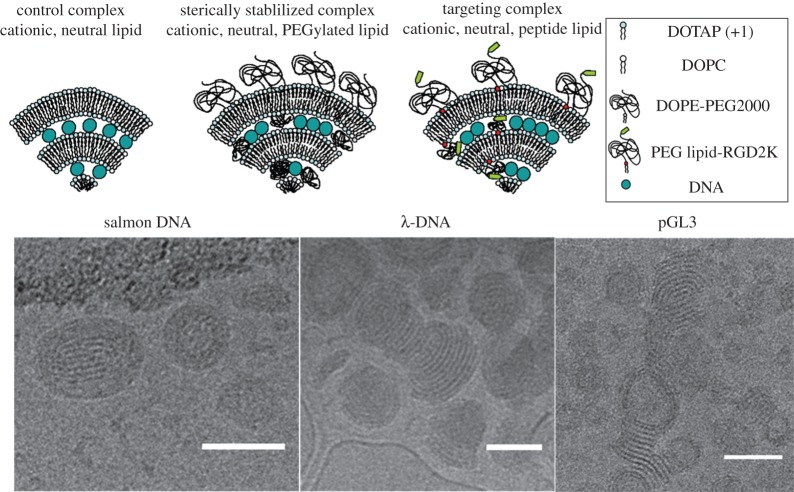

A major drawback of CL–DNA complexes (figure 3, top, left cartoon of the lamellar onion-like phase) is their relatively short circulation times in vivo due to opsonization of complexes and macrophage clearance [41,42]. In order to overcome this obstacle, polyethylene glycol (PEG) is often grafted to the surface of the complex (figure 3, top, middle cartoon). This is achieved by preparing CLs which, in addition to cationic and neutral lipids, also contain lipids with PEG covalently attached to their headgroups [43–50]. The added PEG polymer coat induces repulsive interactions with a range on the scale of the size of the polymer chain [51–54]. Complexes which contain sufficient PEG-lipids (such that the PEG chains transition from the mushroom to the brush conformation) sterically stabilize CL–DNA complexes against flocculation caused by van der Waals attractions [55–57]. Experiments have shown that PEGylated complexes resist aggregation even after extensive centrifugation [40]. Thus, the use of a PEG-lipid improves colloidal stability, and as experiments show PEGylation leads to the spontaneous formation of equilibrium nanoparticles (NPs). In vivo studies have verified that the PEG polymer coat inhibits protein binding to the surface, preventing immune cell clearance [58–60].

Figure 3.

Top: schematic of CL–DNA complexes and nanoparticles (NPs). Complexes without PEG (left); PEGylated NPs (middle); RGD-tagged PEGylated NPs (right). Bottom: cryogenic TEM of PEGylated CL–DNA NPs. (Left) Polydisperse salmon sperm DNA (average length ≈2 kbp) in cationic NPs. Here, ρchg=molar charge ratio of lipid to DNA=3 and DOTAP/DOPC/PE-PEG2K (80/17/3); (middle) 48 kbp λ-phage DNA in cationic NPs at ρchg=3 and DOTAP/DOPC/PE-PEG5K (80/15/5); and (right) pGL3 plasmid (4.8 kbp, used in transfection efficiency assays to measure gene expression) in cationic NPs at ρchg=2 and DOTAP/DOPC/PE-PEG2K (80/10/10) NPs. Scale bars, 50 nm. Adapted with permission from [40]. Copyright © 2015 American Chemical Society.

(a). Cryo-TEM studies of the structures of PEGylated CL–DNA nanoparticles

Dynamic light scattering (DLS) characterization of the hydrodynamic diameter of PEGylated CL–DNA complexes shows that they are inherently nanometre-scale particles with diameters of about 100 to 150 nm [61–64]. While Cryo-TEM studies are consistent with the DLS results, they further reveal (figure 3, bottom) differences in the detailed structure and morphology of PEGylated CL–DNA NPs that depend on DNA length and shape [40]. Figure 3 (bottom, left) shows a micrograph of the nanoscale structures of cationic PEGylated CL–DNA NPs formed with polydisperse linear salmon sperm DNA with an average length of 2 kbp at a lipid molar ratio of 80/15/5 DOTAP/DOPC/PEG2K-lipid and molar charge ratio of lipid to DNA=ρchg=3. The structures appear as locally lamellar oblate and spheroidal NPs. The lamellar structure of the NPs is more clearly evident with monodisperse λ-DNA with length 48 kb (figure 3, bottom, middle micrograph with λ-DNA at ρchg=3 and lipid ratio of 80/10/10 DOTAP/DOPC/PEG5K-lipid). Interestingly, the image also reveals terminated bilayer edges. NPs formed with circular plasmid pGL3 (L≈4.8 kbp) at a lipid molar ratio of 80/10/10 DOTAP/PC/PEG2K-lipid and ρchg=2 also show the lamellar structure and terminated bilayer edges, similar to λ-DNA containing NPs. In contrast with polydisperse salmon sperm DNA, NPs formed with λ-DNA or pGL3 can also exhibit hollow cores in addition to the lamellar morphology from core to surface.

A major drawback of PEGylated complexes is that they suffer from very low TE. This is because the repulsive polymer brush suppresses short-range electrostatic attraction between NPs and cells (i.e. binding of cationic NPs to anionic cell surface proteoglycans) resulting in reduced uptake by the cell. Furthermore, the PEG coat tends to inhibit endosomal escape for the small fraction of NPs that undergo endocytosis [65]. This is because when cells uptake CL–DNA NPs, fusion between the membranes of the NPs and endosomal membranes is a primary pathway for endosomal escape and cytoplasmic delivery [34]. PEGylation suppresses this fusion. Cellular uptake may be recovered by attaching targeting ligands to PEGylated complexes. This allows for targeted delivery and receptor-mediated uptake.

(b). Live-cell optical imaging for determination of intracellular spatial and temporal distribution of CL–DNA nanoparticles

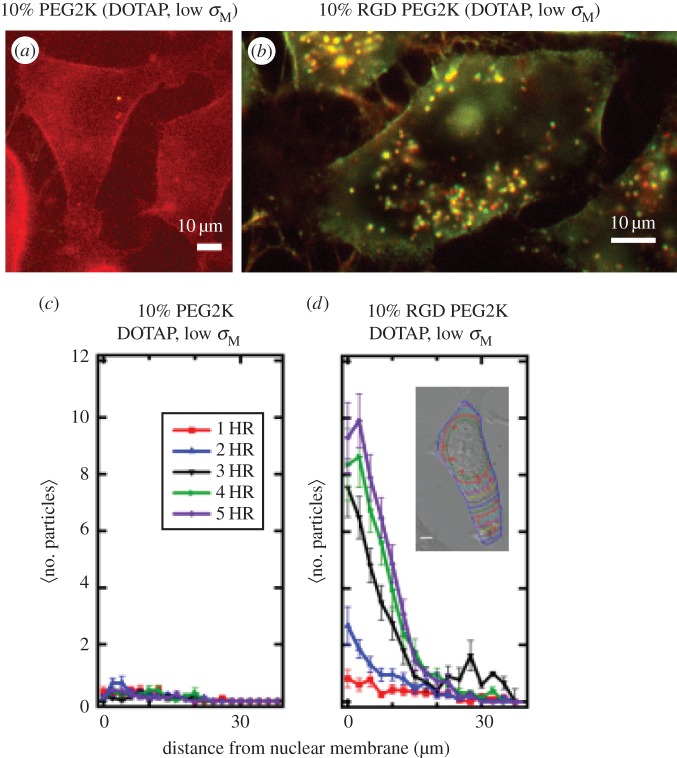

A recent live-cell imaging study with quantitative particle tracking yielded the intracellular distribution of complexes and directly confirmed the increased rate of complex uptake when PEG2K-lipid is replaced by RGD-PEG2K-lipid as the NP polymer coat (figure 4) [61,66]. The employed linear RGD peptide binds to the cell’s α5β1integrins, initiating receptor-mediated endocytosis [67–70].

Figure 4.

Live-cell imaging results of PEGylated and RGD-PEGylated CL–DNA nanoparticles (NPs) contrasting non-specific and specific uptake (a,b). Fluorescent images of low-σM DOTAP/DOPC (30/60, mol/mol)–DNA complexes with 10 mol% of either PEG2K-lipid (a) or RGD-PEG2K-lipid (b). Images at 5 h after NP addition (dual channel (Cy5-DNA (670 nm emission), TRITC-lipid (580 nm emission)) fluorescence; complexes at ρchg=molar charge ratio of lipid to DNA=10; mouse L-cells). These images at low membrane charge density (σM=0.005 e Å−2) show a dramatic increase in complex uptake when a linear RGD peptide targeting cell integrins is attached to the distal end of PEG2K (cf. a with b). Scale bars in (a,b) are 10 μm. (c,d) Quantitative particle tracking results of (a,b), averaged over 20 cells. The data show the intracellular distribution of NPs as a function of distance from the nucleus for 1 h through 5 h after NP addition. Low-σM PEG2K-coated complexes show ≈no uptake (c; cf. with a), while low-σM RGD-PEG2K-coated complexes are taken up soon after addition (d; cf. with b). (Inset to d) Contour lines in a typical cell show the boundaries used to define distance from nuclear membrane. Adapted from [61] with permission from Elsevier.

Figure 4a,c show that NPs with a low membrane charge density (σM=0.005 e Å−2, DOTAP/DOPC 30/60 (mol/mol)) containing 10 mol% PEG2K-lipid show nearly no uptake even 5 h after addition of NPs to cells. This is indicative of near complete suppression of electrostatic binding due to the PEG2K repulsive barrier. By contrast, NPs with the same low σM but containing linear RGD-PEG2K-lipid exhibit significant cellular uptake through specific RGD-integrin binding (figure 4b,d). Quantitative image analysis of the intracellular distribution of NPs as a function of time (where the number of fluorescent NPs is measured as a function of distance from the nucleus, see inset in figure 4d) shows strong uptake for RGD-tagged PEGylated NPs (figure 4d) versus virtually no uptake for PEGylated NPs (figure 4c). The live-cell imaging results are consistent with TE measurements, which show that suppression of TE for PEGylated NPs is partially overcome with RGD-tagged PEGylated NPs [61].

A recent study has shown that a PEG-lipid (termed HPEG-lipid) bearing an acid-labile acylhydrazone bond between the lipid headgroup and the PEG chain enhances endosomal escape of PEGylated NPs [62]. HPEG2K-lipid is stable at pH=7 and the PEG2K chains are cleaved from the lipid tail at pH=5. Indeed, NPs containing 10 mol% HPEG2K-lipid show partial recovery of TE compared with NPs containing 10 mol% PEG2K-lipid. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the low pH (≈4) of late endosomes induces dePEGylation, which in turn leads to membrane charge density-promoted endosomal escape by activated fusion [33,34,62]. Future studies with NPs which combine RGD-PEG2K-lipid and HPEG2K-lipid in an optimized molar ratio should lead to even higher TE resulting from both optimized targeting and uptake, and endosomal escape.

4. Fluorescence microscopy of lipid–nucleic acid nanoparticles with mutant Rab5-GFP: visualization of single nanoparticle behaviour inside giant endosomes

A previous study reported on three-dimensional images of CL–DNA complexes interacting with cells obtained via confocal microscopy [34]. In particular, those earlier studies showed that the interaction of complexes and cells was dependent on the CL–DNA complex self-assembly structure (i.e. lamellar versus inverse hexagonal). However, while highly informative, those earlier studies were not able to provide information, in a direct manner, on the mechanism of cell entry, which was hypothesized to be through endocytosis, and on intracellular pathways.

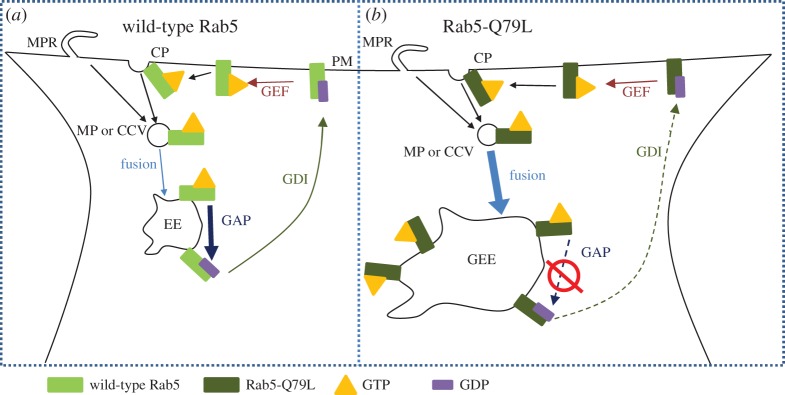

Fluorescence microscopy and automated particle colocalization with wild-type Rab5-GFP and Rab5-Q79L-GFP (a slowly hydrolysing mutant, figure 5) has been recently employed to measure, upon binding and cell uptake, colocalization of RGD-tagged CL–DNA NPs and early endosomes (EEs) in mammalian cells [63]. Rab5 is a member of a large family of GTPases that coordinate intracellular vesicle budding, trafficking and fusion between membrane organelles and between the plasma and organelle membranes [71]. Rab5 is localized to the plasma membrane, EEs and phagosomes. It plays a critical role in the formation of EEs [71–73]. Figure 5a shows a Rab5 cycle during endocytosis. Rab5-GTP is known to accumulate at the sites of clathrin-coated pits and macropinocytic ruffles where it is involved in the recruitment of proteins for endosomal budding from the plasma membrane [74–76]. Rab5-GTP interacts with effector macromolecules, which mediate homotypic fusion between GTP-Rab5 containing endocytic vesicles [77,78]. After GTP hydrolysis, Rab5-GDP complexes with guanosine nucleotide disassociation inhibitor, which facilitates cytoplasmic transport back to the plasma membrane. Guanine nucleotide exchange factor then converts Rab5-GDP to Rab5 GTP, completing the cycle [79]. Rab5-GDP cannot mediate endosome fusion and is inactive [77]. During the process where EEs gradually lose Rab5 after GTP hydrolysis, they simultaneously accumulate Rab7, marking the maturation process of EEs into late endosomes [80].

Figure 5.

Schematic drawing highlighting differences in wild-type Rab5 and mutant Rab5-Q79L cycles. (a) GTP-bound Rab5 (Rab5-GTP) is recruited to the lumen side of clathrin pits (CP) or macropinocytotic ruffles (MPR). Once the macropinosome (MP) or clathrin-coated vesicle (CCV) has pinched off from the plasma membrane (PM), Rab5-GTP mediates homotypic fusion with similar Rab5-GTP containing vesicles leading to the formation of early endosomes (EEs). GTPase activating protein (GAP) hydrolyses Rab5-GTP on EEs. Rab5-GDP complexes with guanosine nucleotide disassociation inhibitor (GDI) and undergoes cytoplasmic transport back to the PM. At the PM the cycle is completed once guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) promotes exchange of GDP with GTP. (b) In the case of mutant Rab5-Q79L, GTP hydrolysis through GAP is strongly suppressed resulting in two phenotypic changes. First, because fusion of MPs and CCVs is mediated by Rab5-GTP, reduced GTP hydrolysis increases the total number of fusion events experienced by EEs, leading to the formation of giant early endosomes (GEEs) that contain weakly hydrolysable Rab5-Q79L on the membrane. Second, loss of Rab5 from the EE through GTP hydrolysis (followed by accumulation of Rab7) is necessary for maturation of EEs into late endosomes, thus the reduced GTP hydrolysis of Rab5-Q79L delays maturation and extends the lifetime of EEs. Adapted from [63] with permission from Elsevier.

A different set of events occur when cells express a mutant form of Rab5-GTP with a point mutation, labelled Rab5-Q79L, which significantly slows down GTP hydrolysis [77] (figure 5b). EEs containing mutant Rab5-Q79L continuously fuse, leading to the formation of giant early endosomes (GEEs) [81]. In contrast with EEs, GEEs are longer lived and have a size of the order of several micrometres. This means that not only is the endosomal lumen clearly visible but, most remarkably, individual NPs are also resolvable within it.

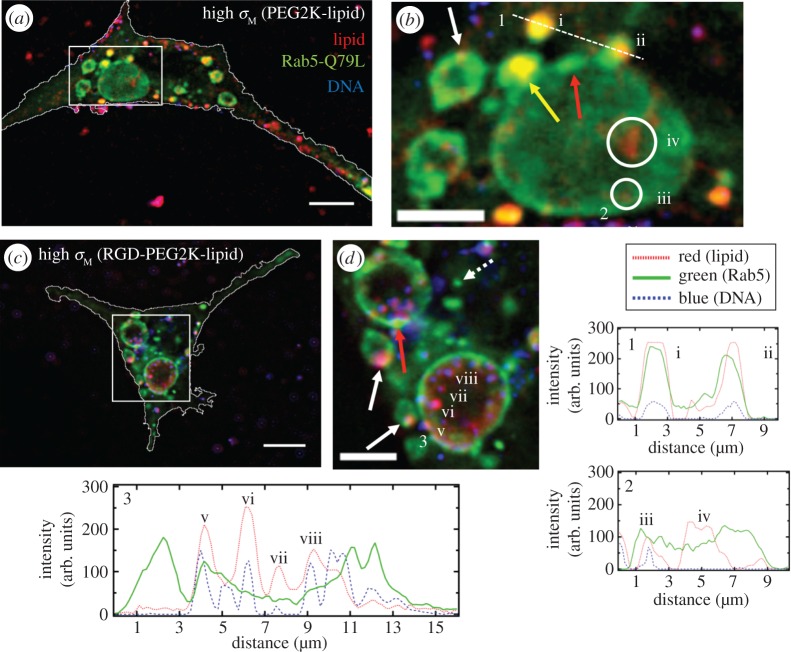

One can see a significant number of GEEs inside the cells resulting from the expression of mutant Rab5-Q79L-GFP (figure 6). In addition, a few much smaller EEs, which have not yet fused with other EEs, are also observed (dashed arrow in figure 6d). It is noteworthy to point out that GEEs tend to show non-uniform GFP fluorescence in their perimeter indicative of membrane sections rich in Rab5-Q79L-GFP (red arrows in figure 6b,d). This is most likely due to recent events where EEs have fused with GEEs. Additionally, the micrographs offer direct evidence of medium-sized, NP-containing EEs undergoing fusion with a GEE (figure 6b, yellow arrow and (ii)). Comparison between the two types of NPs shows that in the case of NPs without the RGD motif, fewer NPs colocalize with GEEs (figure 6b(i–iii)) relative to those where RGD is attached to the distal end of PEG (see NPs in magnified images figure 6d including (v–viii). The CL uptake observed in the large GEE in figure 6b(iv) is expected because CLs coexist with NPs for ρ>1 [28,29]. Significantly, the existence of GEEs in cells expressing Rab5-Q79L allows one to spatially resolve individual RGD-tagged NPs within GEEs (figure 6d(v–viii) and corresponding intensity profile 3). This ability to resolve individual NPs has led to images which strongly hint at RGD-tagged NPs adhering to GEE membranes in the case of high σM (figure 6d(v) and white arrows).

Figure 6.

Colocalization of cationic liposome–DNA nanoparticles (CL–DNA NPs) and giant early endosomes (GEEs). Rab5-Q79L inhibits endosome maturation, giving rise to large (greater than 5 μm) endosomes with spatially resolvable NPs. Nearly all intracellular CL–DNA NPs are foundwithin Rab5-Q79L-GFP labelled endosomes (red, TRITC (lipid); green, GFP (endosomes); blue, Cy5 (DNA)). All cells shown were fixed after 1 h of incubation at 4°C followed by 1 h of incubation at 37°C. (a,c) Fluorescent micrographs and cell boundaries (white outlines) of L-cells with (a) PEGylated high-σM NPs (MVL5/DOPC/PEG2K-lipid at a molar ratio of 50/40/10), (c) RGD-tagged high-σM NPs (MVL5/DOPC/RGD-PEG2K-lipid at a molar ratio 50/45/5). (b,d) High magnification of boxed regions in (a,c). (1–3) Intensity profiles of labelled scans from high magnification regions. Intensity profiles 1 and 2 show NPs (i,ii,iii) and liposomes (iv) found in EEs (i, ii) and GEEs (iii).Intensity profile 3 shows clear evidence of individually resolvable NPs (v,vi,vii,viii) inside the lumen of the GEE including a NP interacting with the inner membrane of the GEE (v). The yellow arrow in (b) points to an EE containing a NP fusing with a GEE. Red arrows in (b,d) show GFP-rich regions of the GEE membrane. Dashed arrow in (d) shows a smaller EE, similar to what is observed with wild-type Rab5. Solid white arrows in (b,d) point to clear examples of NPs adhering to the GEE membrane. Scale bars in (a,c) and (b,d) are 10 μm and 5 μm, respectively. Adapted from [63] with permission from Elsevier.

This study has led to the development of a robust imaging assay which allows one to directly visualize trapped NPs and their interactions with the luminal membrane of giant endosomes. Significantly, it suggests that colocalization studies of NPs in cells expressing mutant Rab5-Q79L is an effective imaging technique for designing new NPs and, through visualization, assessing whether they are efficient at endosomal escape.

5. Concluding remarks and future directions

The long-term goal of developing suitable surface functionalized CL–nucleic acid NPs for gene delivery and gene silencing necessitates the implementation of several complementary techniques. Live-cell colocalization imaging has the potential of providing direct information on NP intracellular spatial and temporal distribution, leading to important insights into the interactions of NPs with cell components and organelles. In this review, we described a recently developed technique [63], which combines fluorescence imaging and automated particle colocalization with the use of a novel mutated Rab-GTP enzyme in order to access direct information on the behaviour of individual NPs trapped inside GEEs. In the example shown in this review, NPs are seen inside giant endosomes and also interacting with the inner membrane wall of the organelles. The lipid composition of GEEs is closely related to those of EEs. Thus, the work has the potential of leading to unprecedented insight into the nature of interactions between NPs and encapsulating endosomes. These types of studies are destined to unravel the mechanisms by which NPs escape endosomes and navigate intracellular pathways, which is a crucial property of NPs designed for delivery of therapeutic molecules.

In order to fully understand and interpret the live-cell imaging data one needs to simultaneously characterize the structure and physico-chemical properties of the NPs (e.g. membrane charge density, lipid shape and charge). This is because the nature of NP interactions with cell components (organelle membranes and cytoskeletal filaments) is dependent not only on the charge of the NP but also on its size (i.e. the NP has to navigate the mammalian cytoskeleton with mesh size ≈200 nm) and its internal nanostructure (which may be obtained by X-ray scattering and cryo-TEM).

Data from direct optical imaging techniques in conjunction with those obtained from NP characterization by cryo-TEM, X-ray diffraction and DLS will allow one to correlate NP self-assembled structure and physico-chemical properties to biological activity measured in TE studies. Optimization of CL–DNA and CL–siRNA NPs in vitro with primary cancer cells is expected to have important implications for both the clinical study of gene therapy in vivo as well as the use of silencing and transfection in vitro as applied to functional genomics.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding

The authors are grateful for the support provided by the US National Institutes of Health under award R01 GM 59288 (transfection efficiency and colocalization studies with Rab GTPases) and the National Science Foundation under award DMR 1401784 (lipid–nucleic acid phase behaviour, nanoparticle imaging and automated image analysis).

References

- 1.Gene Therapy Clinical Trials Worldwide. See http://www.wiley.com/legacy/wileychi/genmed/clinical/ (accessed October 2015).

- 2.Felgner PL, Gadek TR, Holm M, Roman R, Chan HW, Wenz M, Northrop JP, Ringold GM, Danielsen M. 1987. Lipofection: a highly efficient, lipid-mediated DNA-transfection procedure. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 84, 7413–7417. ( 10.1073/pnas.84.21.7413) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu N, Liggitt D, Liu Y, Debs R. 1993. Systemic gene expression after intravenous DNA delivery into adult mice. Science 261, 209–211. ( 10.1126/science.7687073) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nabel GJ. et al. 1993. Direct gene transfer with DNA-liposome complexes in melanoma: expression, biologic activity, and lack of toxicity in humans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 11 307–11 311. ( 10.1073/pnas.90.23.11307) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Safinya CR, Ewert KK, Majzoub RN, Leal C. 2014. Cationic liposome–nucleic acid complexes for gene delivery and gene silencing. New J. Chem. 38, 5164–5172. ( 10.1039/c4nj01314j) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guo X, Huang L. 2012. Recent advances in nonviral vectors for gene delivery. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 971–979. ( 10.1021/ar200151m) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bielke W, Erbacher C. (eds) 2010. Nucleic acid transfection. Topics in Current Chemistry, vol. 296. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ewert KK, Zidovska A, Ahmad A, Bouxsein NF, Evans HM, McAllister CS, Samuel CE, Safinya CR. 2010. Cationic liposome–nucleic acid complexes for gene delivery and silencing: pathways and mechanisms for plasmid DNA and siRNA. In Nucleic acid transfection (eds W Bielke, C Erbacher). Topics in Current Chemistry, vol. 296, pp. 191–226. Berlin, Germany: Springer ( 10.1007/128_2010_70) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang L, Hung MC, Wagner E (eds).. 2005. Advances in genetics, vol. 53: non-viral vectors for gene therapy, 2nd edn San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ewert K, Ahmad A, Evans H, Safinya C. 2005. Cationic lipid-DNA complexes for non-viral gene therapy: relating supramolecular structures to cellular pathways. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 5, 33–53. ( 10.1517/14712598.5.1.33) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ewert K, Evans HM, Ahmad A, Slack NL, Lin AJ, Martin-Herranz A, Safinya CR. 2005. Lipoplex structures and their distinct cellular pathways. In Advances in genetics: non-viral vectors for gene therapy, vol. 53 (eds L Huang, MC Hung, E Wagner), 2nd edn, pp. 119–155. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ewert K, Slack NL, Ahmad A, Evans HM, Lin AJ, Samuel CE, Safinya CR. 2004. Cationic lipid-DNA complexes for gene therapy: understanding the relationship between complex structure and gene delivery pathways at the molecular level. Curr. Med. Chem. 11, 133–149. ( 10.2174/0929867043456160) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Safinya CR, Lin AJ, Slack NL, Koltover I. 2002. Structure and structure-activity correlations of cationic lipid/DNA complexes: supramolecular assembly and gene delivery. In Pharmaceutical perspectives of nucleic acid-based therapeutics (eds RI Mahato, SW Kim), pp. 190–209. London, UK: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang L, Hung M-C, Wagner E (eds). 1999. Nonviral vectors for gene therapy. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safinya CR, Koltover I. 1999. Self-assembled structures of lipid/DNA nonviral gene delivery systems from synchrotron X-ray diffraction. In Nonviral vectors for gene therapy (eds L Huang, M-C Hung, E Wagner), pp. 91–117. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams DA, Baum C. 2003. Gene therapy—new challenges ahead. Science 302, 400–401. ( 10.1126/science.1091258) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomas CE, Ehrhardt A, Kay MA. 2003. Progress and problems with the use of viral vectors for gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4, 346–358. ( 10.1038/nrg1066) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hacein-Bey-Abina S. et al. 2008. Insertional oncogenesis in 4 patients after retrovirus-mediated gene therapy of SCID-X1. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 3132–3142. ( 10.1172/jc135700) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harrington JJ, Van Bokkelen G, Mays RW, Gustashaw K, Willard HF. 1997. Formation of de novo centromeres and construction of first-generation human artificial microchromosomes. Nat. Genet. 15, 345–355. ( 10.1038/ng0497-345) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spagnou S, Miller AD, Keller M. 2004. Lipidic carriers of siRNA: differences in the formulation, cellular uptake, and delivery with plasmid DNA. Biochemistry 43, 13 348–13 356. ( 10.1021/bi048950a) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouxsein NF, McAllister CS, Ewert KK, Samuel CE, Safinya CR. 2007. Structure and gene silencing activities of monovalent and pentavalent cationic lipid vectors complexed with siRNA. Biochemistry 46, 4785–4792. ( 10.1021/bi062138l) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fire A, Xu SQ, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. 1998. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391, 806–811. ( 10.1038/35888) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McManus MT, Sharp PA. 2002. Gene silencing in mammals by small interfering RNAs. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 737–747. ( 10.1038/nrg908) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sioud M, Sørensen DR. 2003. Cationic liposome-mediated delivery of siRNAs in adult mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 312, 1220–1225. ( 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.057) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Akinc A. et al. 2008. A combinatorial library of lipid-like materials for delivery of RNAi therapeutics. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 561–569. ( 10.1038/nbt1402) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gindy ME, Leone AM, Cunningham JJ. 2012. Challenges in the pharmaceutical development of lipid-based short interfering ribonucleic acid therapeutics. Expert Opin. Drug Delivery 9, 171–182. ( 10.1517/17425247.2012.642363) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rädler JO, Koltover I, Salditt T, Safinya CR. 1997. Structure of DNA-cationic liposome complexes: DNA intercalation in multilamellar membranes in distinct interhelical packing regimes. Science 275, 810–814. ( 10.1126/science.275.5301.810) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koltover I, Salditt T, Rädler JO, Safinya CR. 1998. An inverted hexagonal phase of cationic liposome-DNA complexes related to DNA release and delivery. Science 281, 78–81. ( 10.1126/science.281.5373.78) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koltover I, Salditt T, Safinya CR. 1999. Phase diagram, stability, and overcharging of lamellar cationic lipid–DNA self-assembled complexes. Biophys. J. 77, 915–924. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76942-0) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Safinya CR. 2001. Structures of lipid–DNA complexes: supramolecular assembly and gene delivery. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 11, 440–448. ( 10.1016/S0959-440X(00)00230-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ewert K, Ahmad A, Evans HM, Schmidt HW, Safinya CR. 2002. Efficient synthesis and cell-transfection properties of a new multivalent cationic lipid for nonviral gene delivery. J. Med. Chem. 45, 5023–5029. ( 10.1021/jm020233w) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ewert KK, Evans HM, Bouxsein NF, Safinya CR. 2006. Dendritic cationic lipids with highly charged headgroups for efficient gene delivery. Bioconjugate Chem. 17, 877–888. ( 10.1021/bc050310c) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad A, Evans HM, Ewert K, George CX, Samuel CE, Safinya CR. 2005. New multivalent cationic lipids reveal bell curve for transfection efficiency versus membrane charge density: lipid–DNA complexes for gene delivery. J. Gene Med. 7, 739–748. ( 10.1002/jgm.717) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin AJ, Slack NL, Ahmad A, George CX, Samuel CE, Safinya CR. 2003. Three-dimensional imaging of lipid gene-carriers: membrane charge density controls universal transfection behavior in lamellar cationic liposome-DNA complexes. Biophys. J. 84, 3307–3316. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70055-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ewert KK, Evans HM, Zidovska A, Bouxsein NF, Ahmad A, Safinya CR. 2006. A columnar phase of dendritic lipid-based cationic liposome-DNA complexes for gene delivery: hexagonally ordered cylindrical micelles embedded in a DNA honeycomb lattice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 3998–4006. ( 10.1021/ja055907h) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leal Cl, Bouxsein NF, Ewert KK, Safinya CR. 2010. Highly efficient gene silencing activity of siRNA embedded in a nanostructured gyroid cubic lipid matrix. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 16 841–16 847. ( 10.1021/ja1059763) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leal C, Ewert KK, Shirazi RS, Bouxsein NF, Safinya CR. 2011. Nanogyroids incorporating multivalent lipids: enhanced membrane charge density and pore forming ability for gene silencing. Langmuir 27, 7691–7697. ( 10.1021/la200679x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leal C, Ewert KK, Bouxsein NF, Shirazi RS, Li Y, Safinya CR. 2013. Stacking of short DNA induces the gyroid cubic-to-inverted hexagonal phase transition in lipid–DNA complexes. Soft Matter 9, 795–804. ( 10.1039/c2sm27018h) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chan C-L, Ewert KK, Majzoub RN, Hwu Y-K, Liang KS, Leal C, Safinya CR. 2014. Optimizing cationic and neutral lipids for efficient gene delivery at high serum content. J. Gene Med. 16, 84–96. ( 10.1002/jgm.2762) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Majzoub RN, Ewert KK, Jacovetty EL, Carragher B, Potter CS, Li Y, Safinya CR. 2015. Patterned threadlike micelles and DNA-tethered nanoparticles: a structural study of PEGylated cationic liposome–DNA assemblies. Langmuir 31, 7073–7083. ( 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b00993) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lasic DD. (ed.). 1997. Liposomes in gene delivery. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lasic DD, Martin F (eds). 1995. Stealth liposomes. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woodle MC, Newman M, Collins L, Redemann C, Martin F. 1990. Improved long circulating (Stealth®) liposomes using synthetic lipids. In Proc. 17th Int. Symp. on Controlled Release Bioactive Material (ed. VHL Lee), pp. 77–78. Lincolnshire, IL: Control Release Society. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klibanov AL, Maruyama K, Torchilin VP, Huang L. 1990. Amphipathic polyethyleneglycols effectively prolong the circulation time of liposomes. FEBS Lett. 268, 235–237. ( 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81016-h) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Blume G, Cevc G. 1990. Liposomes for the sustained drug release in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1029, 91–97. ( 10.1016/0005-2736(90)90440-Y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papahadjopoulos D. et al. 1991. Sterically stabilized liposomes: improvements in pharmacokinetics and antitumor therapeutic efficacy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 88, 11 460–11 464. ( 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11460) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Allen TM, Hansen C, Martin F, Redemann C, Yau-Young A. 1991. Liposomes containing synthetic lipid derivatives of poly(ethylene glycol) show prolonged circulation half-lives in vivo. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1066, 29–36. ( 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90246-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woodle MC, Lasic DD. 1992. Sterically stabilized liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1113, 171–199. ( 10.1016/0304-4157(92)90038-c) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Papahadjopoulos D. 1995. Stealth liposomes: from steric stabilization to targeting. In Stealth liposomes (eds DD Lasic, F Martin), pp. 1–6. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silvander M. 2002. Steric stabilization of liposomes—a review. In Lipid and polymer-lipid systems (eds T Nylander, B Lindman), pp. 35–40. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 51.De Gennes P-G. 1979. Scaling concepts in polymer physics. New York, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Needham D, McIntosh TJ, Lasic DD. 1992. Repulsive interactions and mechanical stability of polymer-grafted lipid membranes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1108, 40–48. ( 10.1016/0005-2736(92)90112-Y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kuhl TL, Leckband DE, Lasic DD, Israelachvili JN. 1994. Modulation of interaction forces between bilayers exposing short-chained ethylene oxide headgroups. Biophys. J. 66, 1479–1488. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)80938-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kenworthy AK, Hristova K, Needham D, McIntosh TJ. 1995. Range and magnitude of the steric pressure between bilayers containing phospholipids with covalently attached poly(ethylene glycol). Biophys. J. 68, 1921–1936. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(95)80369-3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martin-Herranz A, Ahmad A, Evans HM, Ewert K, Schulze U, Safinya CR. 2004. Surface functionalized cationic lipid-DNA complexes for gene delivery: PEGylated lamellar complexes exhibit distinct DNA-DNA interaction regimes. Biophys. J. 86, 1160–1168. ( 10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74190-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lasic DD. 1993. Liposomes: from physics to applications. San Diego, CA: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Witten TA, Pincus PA. 2004. Structured fluids: polymers, colloids, surfactants. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hong K, Zheng W, Baker A, Papahadjopoulos D. 1997. Stabilization of cationic liposome-plasmid DNA complexes by polyamines and poly(ethylene glycol)-phospholipid conjugates for efficient in vivo gene delivery. FEBS Lett. 400, 233–237. ( 10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01397-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bradley AJ, Devine DV, Ansell SM, Janzen J, Brooks DE. 1998. Inhibition of liposome-induced complement activation by incorporated poly(ethylene glycol)-lipids. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 357, 185–194. ( 10.1006/abbi.1998.0798) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kostarelos K, Miller AD. 2005. Synthetic, self-assembly ABCD nanoparticles; a structural paradigm for viable synthetic non-viral vectors. Chem. Soc. Rev. 34, 970–994. ( 10.1039/b307062j) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Majzoub RN, Chan C-L, Ewert KK, Silva BFB, Liang KS, Jacovetty EL, Carragher B, Potter CS, Safinya CR. 2014. Uptake and transfection efficiency of PEGylated cationic liposome–DNA complexes with and without RGD-tagging. Biomaterials 35, 4996–5005. ( 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chan C-L, Majzoub RN, Shirazi RS, Ewert KK, Chen Y-J, Liang KS, Safinya CR. 2012. Endosomal escape and transfection efficiency of PEGylated cationic liposome–DNA complexes prepared with an acid-labile PEG-lipid. Biomaterials 33, 4928–4935. ( 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.038) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Majzoub RN, Chan C-L, Ewert KK, Silva BFB, Liang KS, Safinya CR. 2015. Fluorescence microscopy colocalization of lipid–nucleic acid nanoparticles with wildtype and mutant Rab5–GFP: a platform for investigating early endosomal events. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1848, 1308–1318. ( 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.03.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Silva BFB, Majzoub RN, Chan C-L, Li Y, Olsson U, Safinya CR. 2014. PEGylated cationic liposome–DNA complexation in brine is pathway-dependent. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1838, 398–412. ( 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.09.008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Song LY, Ahkong QF, Rong Q, Wang Z, Ansell S, Hope MJ, Mui B. 2002. Characterization of the inhibitory effect of PEG-lipid conjugates on the intracellular delivery of plasmid and antisense DNA mediated by cationic lipid liposomes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1558, 1–13. ( 10.1016/S0005-2736(01)00399-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Majzoub RN, Ewert KK, Safinya CR. 2015. Quantitative intracellular localization of cationic lipid-nucleic acid nanoparticles with fluorescence microscopy. In Non-viral gene delivery vectors: methods and protocols (ed. G Candiani) Totowa, NJ: Springer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pierschbacher MD, Hayman EG, Ruoslahti E. 1981. Location of the cell-attachment site in fibronectin with monoclonal antibodies and proteolytic fragments of the molecule. Cell 26, 259–267. ( 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90308-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pierschbacher MD, Ruoslahti E. 1984. Cell attachment activity of fibronectin can be duplicated by small synthetic fragments of the molecule. Nature 309, 30–33. ( 10.1038/309030a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pierschbacher MD, Ruoslahti E. 1984. Variants of the cell recognition site of fibronectin that retain attachment-promoting activity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 81, 5985–5988. ( 10.1073/pnas.81.19.5985) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pytela R, Pierschbacher MD, Ruoslahti E. 1985. Identification and isolation of a 140 kd cell surface glycoprotein with properties expected of a fibronectin receptor. Cell 40, 191–198. ( 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90322-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zerial M, McBride H. 2001. Rab proteins as membrane organizers. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 107–117. ( 10.1038/35052055) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gorvel J-P, Chavrier P, Zerial M, Gruenberg J. 1991. rab5 controls early endosome fusion in vitro. Cell 64, 915–925. ( 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90316-Q) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rubino M, Miaczynska M, Lippé R, Zerial M. 2000. Selective membrane recruitment of EEA1 suggests a role in directional transport of clathrin-coated vesicles to early endosomes. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 3745–3748. ( 10.1074/jbc.275.6.3745) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bucci C, Parton RG, Mather IH, Stunnenberg H, Simons K, Hoflack B, Zerial M. 1992. The small GTPase rab5 functions as a regulatory factor in the early endocytic pathway. Cell 70, 715–728. ( 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90306-W) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Horiuchi H, Giner A, Hoflack B, Zerial M. 1995. A GDP/GTP exchange-stimulatory activity for the Rab5-RabGDI complex on clathrin-coated vesicles from bovine brain. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 11 257–11 262. ( 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11257) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lanzetti L, Palamidessi A, Areces L, Scita G, Di Fiore PP. 2004. Rab5 is a signalling GTPase involved in actin remodelling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Nature 429, 309–314. ( 10.1038/nature02542) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stenmark H, Parton RG, Steele-Mortimer O, Lütcke A, Gruenberg J, Zerial M. 1994. Inhibition of rab5 GTPase activity stimulates membrane fusion in endocytosis. EMBO J. 13, 1287–1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Simonsen A. et al. 1998. EEA1 links PI(3)K function to Rab5 regulation of endosome fusion. Nature 394, 494–498. ( 10.1038/28879) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ullrich O, Stenmark H, Alexandrov K, Huber LA, Kaibuchi K, Sasaki T, Takai Y, Zerial M. 1993. Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor as a general regulator for the membrane association of rab proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 18 143–18 150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rink J, Ghigo E, Kalaidzidis Y, Zerial M. 2005. Rab conversion as a mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes. Cell 122, 735–749. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.043) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Roberts RL, Barbieri MA, Pryse KM, Chua M, Morisaki JH, Stahl PD. 1999. Endosome fusion in living cells overexpressing GFP-rab5. J. Cell Sci. 112, 3667–3675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]