Abstract

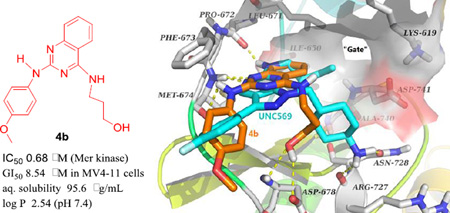

Current results identified 4-substituted 2-phenylaminoquinazoline compounds as novel Mer tyrosine kinase (Mer TK) inhibitors with a new scaffold. Twenty-one 2,4-disubstituted quinazolines (series 4–7) were designed, synthesized, and evaluated against Mer TK and a panel of human tumor cell lines aimed at exploring new Mer TK inhibitors as novel potential antitumor agents. A new lead, 4b, was discovered with a good balance between high potency (IC50 0.68 µM) in the Mer TK assay and antiproliferative activity against MV4-11 (GI50 8.54 µM), as well as other human tumor cell lines (GI50 < 20 µM), and a desirable druglike property profile with low log P value (2.54) and high aqueous solubility (95.6 µg/mL). Molecular modeling elucidated an expected binding mode of 4b with Mer TK and necessary interactions between them, thus supporting the hypothesis that Mer TK might be a biologic target of this kind of new active compound.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

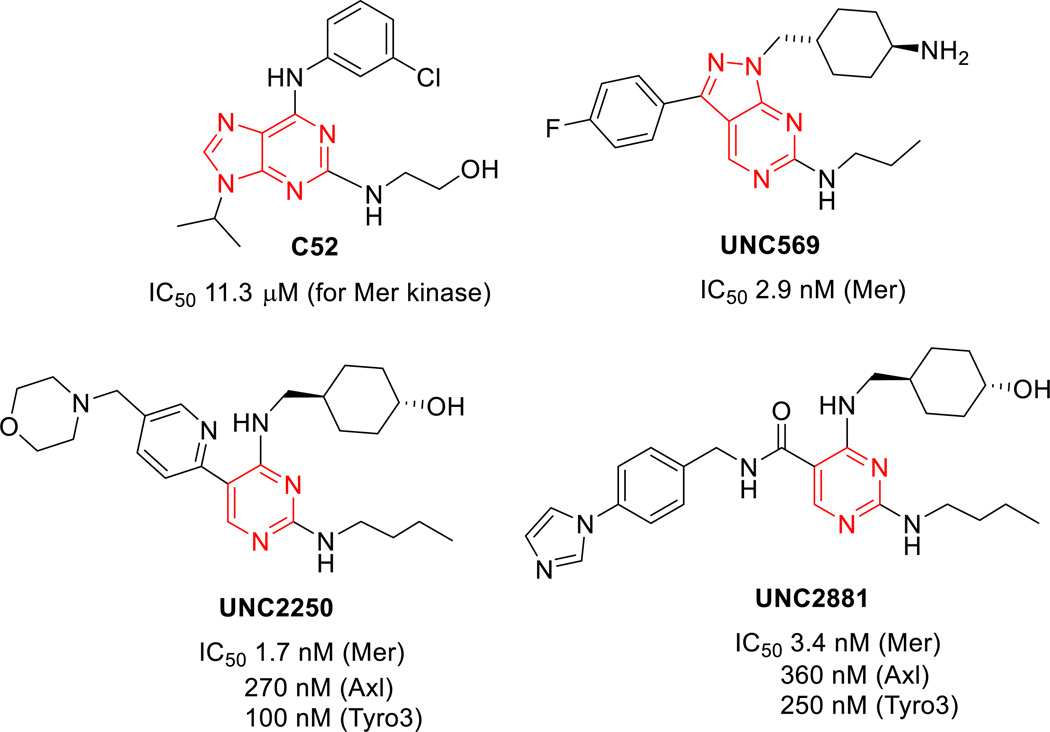

Mer tyrosine kinase (Mer TK) is a member of the TAM (Tyro3/Axl/Mer) kinase family and has been identified as a specific therapeutic target for acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL),1 the most common malignant cancer in children. Despite a significant improvement in ALL treatment in terms of survival (>80%) over the past 40 years,2 novel targeted therapies for pediatric ALL are urgently needed, because current standard therapy treatments induce short- and long-term toxicities,3,4 plus development of resistance and relapse. The Mer TK plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of ALL through initiation of anti-apoptotic signaling via increased phosphorylation of Akt and Erk, and subsequent prevention of cell apoptosis,5 and is ectopically expressed at high-levels in pediatric T- and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemias in vitro and in vivo in contrast to normal lymphocytes.6 The overexpression of Mer TK in T-and B-cells has provided compelling evidence that inhibition of Mer reduces the survival of leukemic cells, makes cells more susceptible to death, and significantly delays the onset of disease in a xenograft mouse model of leukemia.7 Additionally, over- or ectopic-expression of Mer TK is also associated with a wide spectrum of human cancers and other diseases, including thrombosis, autoimmune disease, and retinitis pigmentosa.8 Therefore, the Mer receptor tyrosine kinase is a very promising selective therapeutic target for new anticancer drugs, not only for pediatric ALL, but possibly for other leukemias and adult solid tumors.9 As a new biological target, the crystal structure of Mer TK was first identified by a complex with C-52, a weak Mer inhibitor.10 Subsequently, small molecular Mer kinase inhibitors, including UNC569,11 UNC2250,12 and UNC288113 (Figure 1), with subnanomolar inhibitory potency were discovered and crystal structures of Mer TK complexed with these new ligands have also reported. These results should greatly assist the exploration of novel Mer tyrosine kinase inhibitors for treatment of ALL and other cancers.

Figure 1.

The Mer TK inhibitors reported

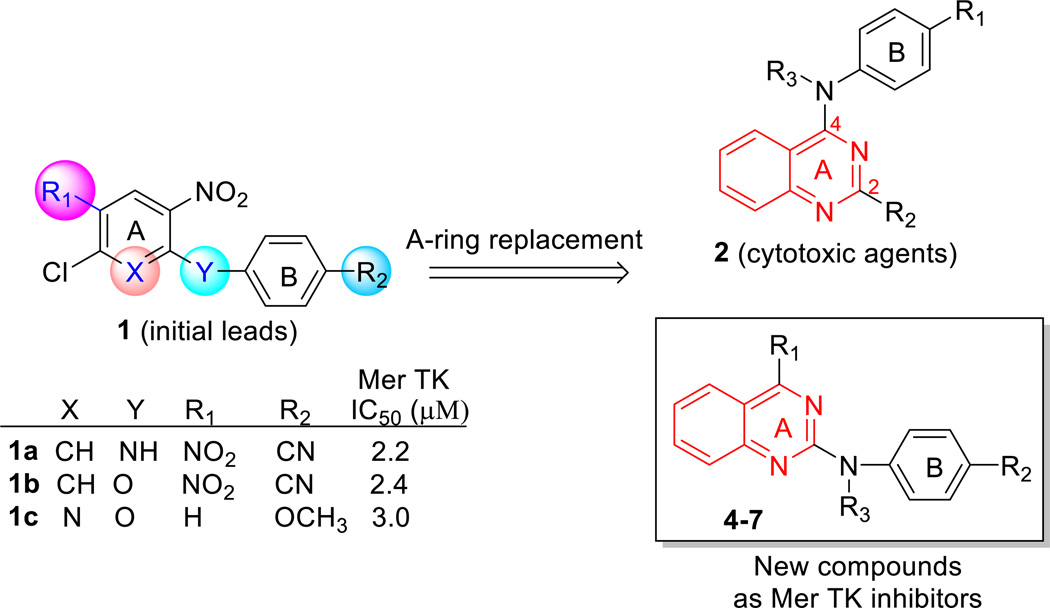

In our prior study, high throughput screening of 72 kinases led to the initial discovery of Mer TK inhibitors leads 1a–c with simple and similar scaffolds (Figure 2). 5-Chloro-N-4-cyanophenyl-2,4-dinitro aniline (1a) and two analogues 1b and 1c showed selective inhibition against Mer tyrosine kinase (IC50 2.2–3.0 µM) without activity against Tyro3 and Axl kinases (IC50 > 30 µM) in the TAM (Tyro3/Axl/Mer) kinase family.14 Meanwhile, the three compounds also clearly exhibited anticancer activity with low micromolar GI50 values ranging from 0.33 to 4.79 µM in a human tumor cell line (HTCL) panel, including A549 (human lung cancer), KB (nasopharyngeal carcinoma), KB-vin (vincristine- resistant KB subline), DU145 (prostate cancer), and K562 (human chronic myelogenous leukemia cells). With this starting point, some structural optimizations were conducted to explore novel Mer kinase inhibitors with a new scaffold as anticancer agents. Based on a structure analysis of several known Mer TK inhibitors as shown in Figure 1, we observed that the pyrimidine ring is a common structural core moiety and appropriate substituents are positioned in a binding orientation at the Mer TK binding site. To increase the probability of generating successful advanced leads, the phenyl or pyridine ring (A-ring) of the initial leads 1a–c was replaced with other bioisosteric aromatic rings in our following lead modifications. After several attempts, the quinazoline ring system was found to be a better structural core moiety, leading to a series of 2-substituted 4-phenylamino-quinazoline compounds 2 (Figure 2) with extremely high antitumor potency (GI50 < 10 nM) in several cellular assays as well as in vivo.15,16,17 However, the series 2 compounds did not show inhibitory activity in Mer TK assays (IC50 >30 µM); thus, their antitumor target is not the Mer TK. However, when the phenylamino moiety (B-ring) was positioned at the 2-position of the quinazoline ring (A ring), the resulting 2-phenylaminoquinazoline compounds exhibited obvious inhibitory potency against Mer TK with low micromolar IC50 values. Therefore, several series of 4-substituted 2-phenylaminoquinazoline compounds (4–7 series) were designed, synthesized, and evaluated in Mer tyrosine kinase and human tumor cell line (HTCL) assays aimed at exploring the new type of Mer TK inhibitor leads. As shown in Figure 2, our structural modifications were focused on the three substituents, R1 at the 4-position on the quinazoline ring (A-ring), R2 on the phenyl ring (B-ring), and R3 on the nitrogen (N) linker between the A- and B-rings, while a phenyl ring was maintained at the 2-position of the quinazoline. Herein, we reported new series of 4-substituted 2-arylaminoquinazolines 4–7, including synthesis, biological activity in Mer TK and cellular assays, assessment of essential physicochemical properties associated with ADMET profiles, and structure-acitivity relationship (SAR) discussion as well as molecular modeling demonstrated at targeting Mer tyrosine kinase.

Figure 2.

Initial leads, modification strategy, and new compounds designed

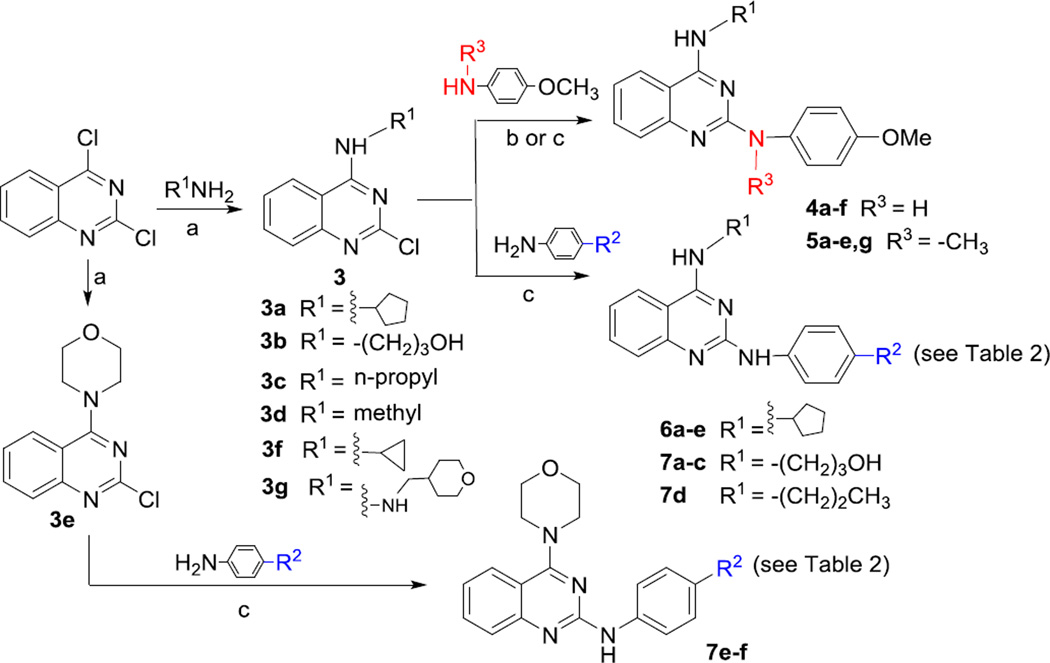

Chemistry

A facilitated synthetic route to target compounds 4–7 is illustrated in Scheme 1. Commercially available 2,4-dichloroquinazoline was coupled with various amines at room temperature in THF for 1 h to preferentially produce 4-alkylamino-2-chloroquinazolines 3a–f in 60–95% yields, due to the higher reactivity of the 4-chloro compared with the 2-chloro position on the quinazoline ring.18 Next, 4-methoxy-N-substituted-anilines were reacted with the 2-chloro on quinazolines 3b–f in the presence of a stronger base t-BuOK and catalyst Pd(OAc)2/X-phos in a mixed solvent of t-BuOH and toluene under microwave irritation at 130 °C to obtain the corresponding 4-alkylamino-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)amino quinazolines 4b–f, respectively, in 33–54% yields. Alternatively, N-methyl-4-methoxyaniline or other para-substituted anilines were coupled with 3a–f in EtOH under microwave irritation at 150 °C to yield target compounds 5a–e, 4a, 6a–e, and 7a–f, respectively. All target compounds were identified by NMR and MS data.

Scheme 1.

(a) THF, rt, < 60 min; (b) t-BuOK (2 equiv.), Pd(OAc)2/X-phos (5% and 4% equiv.), t-BuOH/toluene (v:v 0.5/2.5 mL), microwave, 130 °C, 15 min (for 4b–f); (c) EtOH, microwave, 150 °C, 15–25 min.

Results and discussion

All 4-substituted 2-phenylaminoquinazoline compounds (series 4–7) were first evaluated for inhibition of Mer TK in a high throughput screening platform with staurosporine as a positive control.11 The first two series of 4-substituted 2-(para-methoxyphenyl)aminoquinazolines 4 (R3 = H) and 5 (R3 = Me) were designed to investigate effects of various alkyl groups (R1) at the 4-position of the quinazoline, and their biological data are shown in Table 1. Except 5e and 5f (>30 µM), most series 4 and 5 compounds exhibited obvious inhibitory activity in the Mer TK assay with low micromolar IC50 values of 0.68 to 10.2 µM. These results indicated that the 2-phenylaminoquinazoline is likely a fundamental pharmacophore of this new class of Mer-TK inhibitors. However, comparatively, series 4 compounds were generally as or more potent than corresponding series 5 compounds in the same assay (see 4a vs 5a, 4b vs 5b, 4d vs 5d, and 4e vs 5e), suggesting that the methyl substituent (R3) on the N-linker between the two aryl rings (A and B rings) was not essential for enhanced inhibitory activity against Mer TK. However, the 4-substituent (R1) on the quinazoline ring was modifiable based on the activity shown with a variety of 4-alkylamino groups (R1) from linear chains of different lengths (b–d) or small rings from three- to six-membered (f, a, e, g). The 4-(3-hydroxypropyl)amino linear chain (R1 = NH(CH2)3OH) resulted in the most potent compound 4b with an IC50 value of 0.68 µM in the Mer TK assay, but the presence of a six-membered ring in the R1 substituent (5e and 5g) led to decreased or abolished potency. Subsequently, the impact of the substituent (R2) at the para-position of the phenyl B-ring on biological activity was explored by series 6 and 7, in which R3 on the N-linker is hydrogen (H). Series 6, with the same R1 substituent (4-cyclopentylamino) found in 4a, contained various para-R2 substituents. Compared with 4a (R2 = OMe, IC50 1.08 µM), 6d with a para-hydroxy (R2 = OH) substituent showed a similar low IC50 value of 1.24 µM. Three other series 6 compounds [6b (R2 = NH2), 6c (R2 = F) and 6e (R2 = COOH)] displayed IC50 values from 2.96 to 7.27 µM, three- to seven-fold less potent than 4a, whereas 6a (R2 = CN) was inactive (IC50 >30 µM) in the Mer TK assay. Three of the series 7 compounds (7a–7c) contain the same linear chain R1 group (4-NH(CH2)3OH) found in 4b. Although less potent than 4b, compound 7a (R2 = CN) still exhibited significant potency (IC50 = 1.72 µM), especially, as compared with inactive 6a. Meanwhile, 7b (R2 = NH2) and 7c (R2 = F) were inactive (IC50 >30 µM), in contrast to the corresponding 6b and 6c in the same assay. Moreover, 7d (R1 = 4-propylamino, R2 = F) was less potent (IC50 = 7.84 µM) than the corresponding 4c and 5c (R1 = 4-propylamino, R2 = OMe, R3 = H or Me). Consistent with the results of 5e and 5g, compounds 7e and 7f with a morpholine in the R1 position were inactive (IC50 >30 µM) in the Mer TK assay. Altogether, the current results indicated that both R1 and R2 substituents could affect the potency against Mer TK, even though clear relationships were not always observed. These results demonstrated that a para-methoxy group (R2 = OMe) on the phenyl B-ring was generally more favorable than several other R2 substituents (particularly, COOH, NH2, F) for Mer TK inhibitory potency. Regardless, a R2 group with strong electronegativity (e.g., F) or electron-withdrawing effect (COOH, CN), as either H-bond acceptor or donor, might interfere with the interactions between the small molecule and Mer TK.

Table 1.

Biological activities and physicochemical properties of series 4 and 5

| ||||||||||

| R1 | R3 | IC50 (µM)a Mer TK |

GI50 (µM)b | Propertiesc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A549 | KB | KB-vin | DU145 | MV4-11 | Aq. Sol. (µ g/mL) |

Log P | ||||

| 4a | H | 1.08 | 10.1 | 11.1 | 12.6 | 12.4 | 4.91 | 10.4 | >5 | |

| 5a | Me | 1.14 | 9.4 | 11.7 | 10.1 | 10.2 | 2.70 | 1.11 | >5 | |

| 4b | H | 0.68 | 15.2 | 20.3 | 17.1 | 18.3 | 8.75 | 95.6 | 2.54 | |

| 5b | Me | 2.01 | 13.0 | 24.8 | 30.8 | 30.2 | 70.1 | ND | ND | |

| 4c | H | 3.43 | 3.53 | 5.33 | 5.09 | 4.08 | 5.88 | 4.36 | >5 | |

| 5c | Me | 1.84 | 12.4 | 13.7 | 12.4 | 13.0 | 2.33e | 3.43 | >5 | |

| 4d | H | 2.25 | 16.1 | 14.8 | 17.5 | 14.3 | 3.07 | 6.61 | 3.21 | |

| 5d | Me | 10.2 | 19.9 | 18.7 | 22.9 | 24.3 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 4e | H | 2.06 | 20.1 | 21.0 | 15.3 | 20.1 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 5e | Me | >30 | NDd | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 4f | H | 3.56 | 13.0 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 13.0 | <13.4 | ND | ND | |

| 5g | Me | >30 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Staurosporinef | 0.00081 | |||||||||

| Paclitaxel (nM)f | 4.9 | 2.6 | 948 | 2.6 | ND | |||||

The concentration that inhibits 50% Mer tyrosine kinase;

The concentration inhibits 50% human tumor cell growth, averaged values determined by at least three independent experiments;

active compounds with IC50 <10 µM and GI50 <20 µM were measured by the methods in Reference 19;

not detected;

tested in human chronic myelogenous leukemia (K526) cells;

reference compounds as the passitive control in related assays.

Subsequently, compounds (series 4–7) active in Mer TK assay, except 5e, 5g, 7e, and 7f (IC50 > 30 µM), were further evaluated in cellular assays against a human tumor cell line (HTCL) panel, including A549, KB, KB-vin, and DU145 cell lines, to determine their antiproliferative activity. Paclitaxel was used as the positive reference. As shown in Tables 1 and 2, most of the new compounds exhibited moderate potency with GI50 values less than 20 µM. Notably, similar potencies were generally observed against both KB and drug-resistant KB-vin cell lines, indicating that these compounds are not substrates of Pgp, a membrane efflux-pump protein. Among them, 4c and 7d showed the highest overall antiproliferative potency (GI50 3.53–5.09 µM and 2.5–4.3 µM respectively). Interestingly, compound 7a (R1 = −NH(CH2)3OH, R2 = CN) showed selective potency against A549 (GI50 3.00 µM) and drug-resistant KB-vin (GI50 4.31 µM) cell growth, five- to eight-fold more potent than against DU145 (GI50 18.7 µM) and KB cell lines (GI50 23.7 µM). This result suggested that the R2-group on the B-ring might affect the selectivity in different cell lines. With the criteria of IC50 < 10 µM and GI50 < 30 µM in the above cellular assays, 13 active compounds were chosen and further tested against the MV4-11 (acute leukemia) cell line, because the Mer kinase is especially overexpressed in T- and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Except 5b, most of the tested compounds exhibited low micromolar GI50 values against this cell line, with two- to four-fold higher potency than against the prior four tested cell lines. The high potency and selectivity in MV4-11 cells are supportive for this compound type as new antitumor agents targeting Mer TK.

Table 2.

Biological activities and physicochemical properties of series 6 and 7

| ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | IC50 (µM)a Mer TK |

GI50 (µM)b | Propertyc | ||||||

| A549 | KB | KB-vin | DU145 | MV4-11 | Aq. Sol. (µ g/mL) |

Log P | ||||

| 4a | OMe | 1.08 | 10.1 | 11.1 | 12.6 | 12.4 | 4.91 | 10.4 | >5 | |

| 6a | CN | >30 | >31.3 | >31.3 | >31.3 | >31.3 | NDd | ND | ND | |

| 6b | NH2 | 7.27 | 15.9 | 17.4 | 21.7 | 18.7 | 4.42 | ND | ND | |

| 6c | F | 4.17 | 12.8 | 13.8 | 12.3 | 9.9 | 5.43 | 1.54 | >5 | |

| 6d | OH | 1.24 | 14.8 | 12.1 | 13.6 | 14.3 | 3.00 | 3.10 | 3.95 | |

| 6e | COOH | 2.90 | 28.7 | 25.2 | 19.8 | 27.3 | 7.50 | ND | ND | |

| 4b | OMe | 0.68 | 15.2 | 20.3 | 17.1 | 18.3 | 8.75 | 95.6 | 2.54 | |

| 7a | CN | 1.72 | 3.00 | 23.7 | 4.31 | 18.7 | 2.79 | 7.52 | 2.84 | |

| 7b | NH2 | >30 | 17.1 | 19.7 | 18.7 | 20.8 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 7c | F | >30 | 19.3 | 17.1 | 24.2 | 20.6 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 7d | F | 7.84 | 4.3 | 2.9 | 2.5 | 4.2 | ND | ND | ND | |

| 7e | F | >30 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| 7f | NH2 | >30 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Staurosporinee | 0.00081 | |||||||||

| Paclitaxel (nM)e | 4.9 | 2.6 | 948 | 2.6 | ||||||

IC50 is concentration that inhibits 50% Mer tyrosine kinase;

GI50 is concentration that inhibits 50% human tumor cell growth, and the values were averaged values determined by at least three independent experiments;

active compounds with IC50 <10 µM and GI50 <20 µM were measured by the methods in Reference 19;

not detected;

reference compounds as the passitive control in related assays.

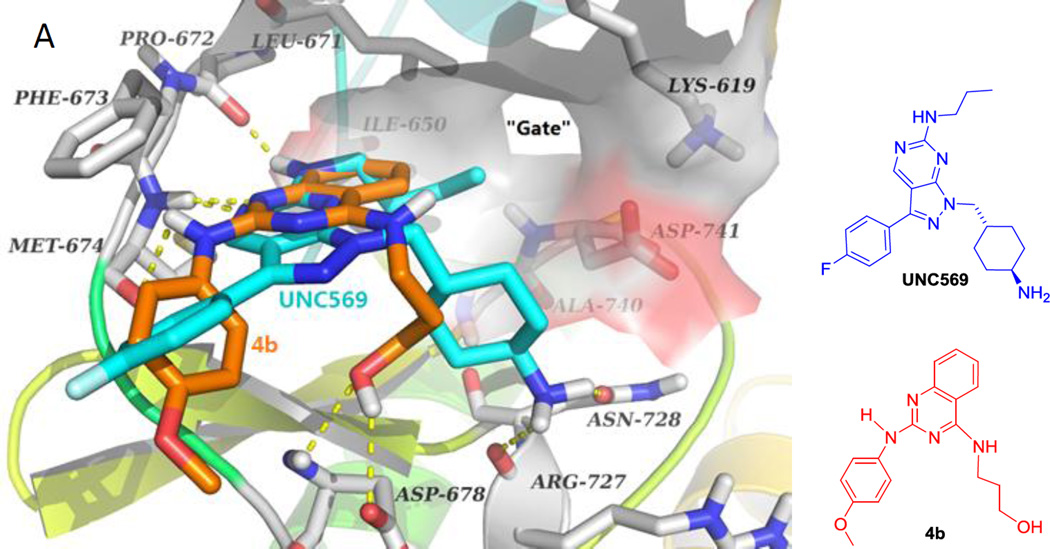

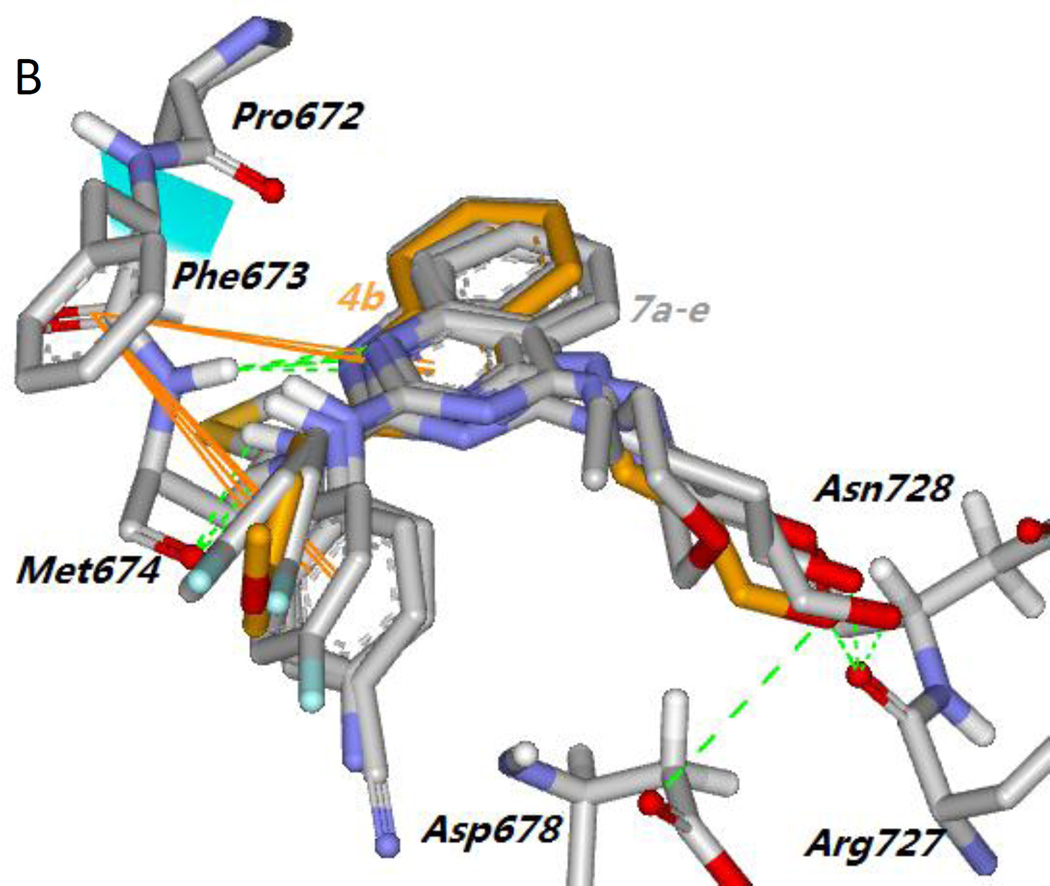

To demonstrate that Mer TK could be a target of the active new compounds, we performed molecular modeling studies with Discovery Studio 3.0 (Accelrys) docking into the ligand-specificity active site of Mer TK mapped by several co-crystal structures of Mer with ligands.10 The crystal structure of Mer kinase in complex with ligand UNC569 (PDB code: 3TCP)11 from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb) was used to dock the most active compound 4b and predict a potential binding mode for 4-alkylamino-2-arylaminoquinazolines. As shown in Figure 3A, the pyrazolopyrimidine ring of original ligand UNC569 (cyan stick) was located near the “gate” of the protein and sustained the orientation and overall binding conformation of its substituents at the Mer TK binding site. Original ligand UNC569 showed four hydrogen bonds with Mer kinase: two within the hinge region produced by the nitrogen on the pyrimidine ring with the NH of residue Met674 as well as the NH of the propylamino side chain with the carbonyl of residue Pro672, and two additional hydrogen bonds from the primary amino group on the methylcyclohexyl moiety with the carbonyls of Arg727 and Asn728, respectively. As expected, representive compound 4b displayed a predicted binding model with Mer TK similar to that of UNC569 as shown in Figure 3. Compound 4b (orange stick) superimposed well with UNC569, having a similar binding orientation and four hydrogen bonds with the Mer kinase site. Two H-bonds were formed between the key amino acid Met674 with the nitrogen on the quinazoline ring and the NH linker of 4b, respectively, supporting the conclusion that a NH linker is favorable for higher potency compared with a methylated N-linker (comparison of series 4 and 5). Two additional H-bonds were produced between the OH in the 4-substituent (R1) of 4b with the backbone carbonyl and amino groups, respectively, of Asp678. In addition, a π-π interaction was observed between the phenyl ring of Phe673 and the quinazoline rings in 4b, which also superimposed over the pyrazolopyrimidine rings of UNC569. The calculated binding free energy of 4b was −18.25 kcal/mol. Therefore, the docking results of 4b supported the possibility that compounds of this new type could act as Mer tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Furthermore, compounds 7a–7e, either active or inactive against Mer TK, were also docked to the Mer TK binding site in the same manner and superimposed with 4b (in orange). As shown in Figure 3B, 7a–7e (in gray) have the same binding orientation as that of 4b and similar interactions around key amino acids Phe673, Met674, and Arg727 (or Asn728). Notably, the π-π interaction between the phenyl ring (B-ring) at the 2-position of the quinazoline with Phe673 was also observed in this series of compounds, thus demonstrating that the 2-phenylamino moiety is a necessary pharmacophore for Mer TK inibition. Meanwhile, different binding conformations of the B-ring moiety in this compound series are also observed in Figure 3B. Thus, molecular potency related with the B-ring conformations could be affected by flexibility of the NH-linker and different para-substituents (R2) on the B-ring.

Figure 3.

(A) Predicted binding mode of 4b (orange) with Mer kinase (PDB code: 3TCP) overlapped with UNC569 (cyan, the original bound ligand of 3TCP). Surrounding amino acid side chains are shown in gray stick format and are labeled. Surface is added on the amino acids Lys619, Leu671, Ile650, Ala740 and Asp741 to show the forming “gate”. Hydrogen bonds are shown by yellow dashed lines, and the distance between ligands and protein is less than 3 Å. Oxyen atoms are red and nitrogen atoms are blue in ligands and amino acid residues. (B) The binding modes of compounds 7a–7e (gray) superimposed on 4b (orange).

To increase drug discovery success, the druglike properties of active compounds mtust also be considered as a prominent component, in addition to potency, during the early stages of lead optimization. Consequently, nine promising compounds, based on the Mer TK (IC50 <5 µM) and MV4-11 cellular (GI50 <10 µM) assay results, were further assessed for essential instrinsic physicochemical properties of aqueous solubility and lipophilicity that are associated with ADME drug properties, potency, and adverse safety. Aqueous solubility and log P values were measured by HPLC methods19 at pH 7.4, similar to the physiological condition in plasma, and the data are listed in Tables 1 and 2. The experimental log P values of 4b, 4d, 6d, and 7a fell within a desirable range of 2.54–3.95 (<4) and the remaining compounds 4a, 5a, 4c, 5c, and 6c possessed higher lipophilicity (log P > 5). Notably, 4b, the most potent compound against Mer TK (IC50 0.68 µM), displayed a desirable log P value of 2.54 and relatively high solubility of 95.6 µg/mL, signifying a good balance that should contribute favorably to better ADME profiles. With the same R1 substituent as 4b, compound 7a also showed a low log P value (2.84) and moderate aqueous solubility (7.52 µg/mL), suggesting that the polar 4-(3-hydroxy)propylamino substituent (R1) in 4b and 7a led to lower molecular lipophilicity. Concomitant with increased molecular lipophilicity, 4d (log P 3.21) and 6d (log P 3.95) displayed decreased aqueous solubilities of 6.61 µg/mL and 3.10 µg/mL, respectively. Based on data comparison of 4a vs 5a and 4c vs 5c in Table 1, the presence of a methyl group (R3) might lead to a decrease in the molecular aqueous solubility. On the other hand, the aqueous solubility results for 4a (R2 = OMe), 6c (R2 = F), and 6d (R2 = OH) revealed the following favorable order: OMe > OH > F.

Conclusion

In the current study, twenty-one 4-substituted 2-phenylaminoquinazolines (series 4–7) were designed, synthesized, and evaluated against Mer TK and a human tumor cell line panel. Among them, 13 compounds showed high inhibitory potency against Mer TK with low micromolar IC50 values ranging from 0.68 to 4.17 µM. Most of these promising compounds also exhibited significant antiproliferative activity against the MV4-11 cell line (IC50 < 10 µM), as well as a broad HTCL panel with moderate IC50 values (< 20 µM). Further assessment of physicochemical properties in vitro identified three new lead compounds 4a, 4b, and 7a with a favorable balance between potency in Mer TK and cellular assays and druglike properties of aqueous solubility and lipophilicity. In particular, compound 4b had an IC50 of 0.68 µM against Mer TK, moderate GI50 values ranging from 8 to 20 µM in cellular assays, a desirable log P value of 2.54, and high aqueous solubility (95.6 µg/mL). Molecular modeling studies predicted a reasonable binding mode of 4b with Mer TK similar to that of the known Mer kinase inhibitor UNC569, supporting our hypothesis that Mer TK might be a biologic target of 4b. Current results demonstrated that (1) the phenylamino moiety at the 2-position on the quinazoline ring (A-ring) is necessary for inhibitory potency against Mer TK; (2) the R1 at the 4-position on the quinazoline ring is modifiable and its H-bonds formed with Asp678, Arg 727, or Asn278 on the binding site of Mer TK are critical to enhance potency in both Mer TK and cellular assays as well as improve drug-like properties; (3) the para-R2 on the phenyl B-ring greatly affects molecular potency, and a methoxy group (OMe) is better than other groups such as OH, NH2, COOH, F; (4) the NH linker between two aryl rings is favorable to enhance molecular potency compared with the methyl group (R3) on the N-linker that might benefit the balance between molcular lipophilicity and aqueous solubility. Therefore, the current studies discovered a series of new Mer TK inhibitors with a 4-substituted 2-phenylaminoquinazoline scaffold and provided helpful directions for further lead optimization aimed at the discovery and development of highly potent and selective Mer inhibitors as novel anticancer agents.

Experimental Section

Chemistry

Melting points were measured on a SGW X-4 Micro-Melting point detector without correction. The proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra were measured on a JNM-ECA-400 (400 MHz) spectrometer using tetramethylsilane (TMS) as internal standard. The solvent used was DMSO unless indicated. Mass spectra (MS) were measured on an API-150EX mass spectrometer with electrospray ionization connected with an Agilent 1100 system. The microwave reactions were performed on a microwave reactor from Biotage, Inc. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on silica gel GF254 plates. Silica gel GF254 and H (200–300 mesh) from Qingdao Haiyang Chemical Company was used for TLC and preparative TLC, respectively. Medium-pressure column chromatography was performed using a CombiFlash companion system from ISCO, Inc. to purify target compounds. All chemicals were obtained from Beijing Chemical Works or Sigma-Aldrich, Inc. The purity of target compounds was measured with HPLC methods and reached >95% for biological assays. The HPLC analyses were performed by using an Agilent 1200 HPLC system with a UV detector and an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column (150 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm) under the conditions of elution with 35–70% acetonitrile (CAN)) in water, flow rate 0.8 mL/min, UV detection at 254 nm, and injection volume of 15 L.

General preparation of 2-chloro-4-(N-substituted)aminoquinazolines 3a–f

A mixture of 2,4-dichloroquinazoline (1.0 equiv) and an amine (2.0 equiv) in THF (ca. 10 mL) was stirred at room temperature for 0.5–3 h monitored by TLC until the reaction finished. After solvent was removed under reduced pressure, solid crude product was washed with water, dried, and purified by flash column chromatography (gradient eluention: EtOAc/petroleum ether, 0–50%) to give corresponding compounds 3a–f in yields of 60–95%. The structures of intermediame 3a and 3b as representive compounds were identified with MS and 1H NMR spectra as indicated below.

2-Chloro-4-(N-cyclopentyl)aminoquinazoline (3a)

Starting with 2,4-dichloro quinazoline (2 g, 10 mmol) and cyclopentanamine (1.7 g, 20 mmol) to produce 2.3 g of 3a in 93 % yield, white solid, mp 108~110 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.61 (4H, m, CH2×2), 1.75 (2H, m, CH2), 2.03 (2H, m, CH2), 4.50 (1H, f, J = 7.2 Hz, CH), 7.53 (1H, td, J = 8.4 and 1.2 Hz, H-6), 7.60 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-5), 7.79 (1H, td, J = 8.4 and 1.2 Hz, ArH-7), 8.37 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-8), 8.46 (1H, d, J = 7.2 Hz, NH); MS m/z (%) 248 (M + 1, 20), 250 (M + 3, 8), 144 (100).

2-Chloro-4-((3-hydroxypropyl)amino)quinazoline (3b)

Starting with 2,4-dichloro quinazoline (2 g, 10 mmol) and 3-aminopropan-1-ol (1.5 g, 20 mmol) to produce 2.2 g of 3b in 92 % yield, white solid, mp 93~95 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.81 (2H, f, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2), 3.52 and 3.57 (each 2H, m, CH2), 4.58 (1H, t, J = 4.8 Hz, OH,), 7.53 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, H-6), 7.61 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.79 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 8.26 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 8.73 (1H, br, NH); MS m/z (%) 238 (M + 1, 40), 240 (M + 3, 13), 144 (100).

General procedure for synthesis of 4b–f

A mixture of a 4-substituted 2-chloroquinazoline (3b–f) (1.0 equiv) and 4-methoxyaniline (1.05–1.5 equiv) in the presence of t-BuOK (2 equiv), X-Phos (0.04 equiv), Pd(OAc)2 (0.05 equiv), and Celite (300 mg) in t-BuOH (0.5 mL) and toluene (2.5 mL) was heated at 130 C for 15 min under microwave irradiation in a closed vial. EtOAc (5 mL) was then added to the mixture, precipitated solid was filtered off, and solvent was removed from the filtrate under reduced pressure to obtain crude products. Purification by flash column chromatography (gradient methanol/DCM ether, 0–5%) provided corresponding pure target compounds.

4-(3-Hydroxypropyl)amino-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)aminoquinazoline (4b)

Starting with 2-chloro- 4-(3-hydroxypropyl)aminoquinazoline (3b) (105 mg, 0.44 mmol) and 4-methoxyaniline (65 mg, 0.52 mmol) to produce 48 mg of 4b in 34% yield, white solid, mp 114~116 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm 1.88 (2H, f, J = 5.6 Hz, CH2), 3.73 (2H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, NCH2), 3.79 (2H, t, J = 5.6 Hz, OCH2) 3.80 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.23 (1H, br, OH), 6.88 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.14 (1H, td, J = 8.0, ArH-6), 7.53~7.58 (3H, m, ArH-5, 7, 8), 7.59 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′); MS m/z (%) 325 (M + 1, 100).

2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)amino-4-propylaminoquinazoline (4c)

Starting with 2-chloro-4-(N-propylamino) quinazoline (3c) (270 mg, 1.22 mmol) and 4-methoxyaniline (225 mg, 1.83 mmol) to produce 204 mg of 4c in 54% yield, yellow solid, mp 220~222 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 0.92 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH3), 1.66 (2H, six, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2), 3.49 (2H, m, CH2,), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 7.01 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.44 (1H, t, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-6), 7.48 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.56 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-5), 7.81(1H, t, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-7), 8.38 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-8), 9.85 (1H, br, NH), 10.32 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 309 (M + 1, 100).

2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)amino-4-methylaminoquinazoline (4d)

Starting with 2-chloro-4-(N-metnyl) aminoquinazoline (3d) (150 mg, 0.78 mmol) and 4-methoxyaniline (120 mg, 0.97 mmol) to produce 73 mg of 4d in 33% yield, faint yellow solid, mp 142~144 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.02 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.72 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.85 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.13 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-6), 7.35 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.55 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 7.83 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.98 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 8.07 (1H, br, NH), 8.87 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 281 (M + 1, 100).

2-(4-Methoxyphenyl)amino-4-(N-morpholino)quinazoline (4e)

Starting with 4-(2-chloroquinazolin-4-yl)morpholine (3e) (130 mg, 0.52 mmol) and 4-methoxyaniline (95 mg, 0.77 mmol) to produce 68 mg of 4e in 39% yield, white solid, mp 141~143 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.63 (4H, t, J = 4.4 Hz, 2 × CH2), 3.73 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.81 (4H, t, J = 4.4 Hz, 2 × CH2), 6.88 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.18 (1H, td, J = 8.0 and 1.2 Hz, ArH-6), 7.49 (1H, dd, J = 8.0 and 1.2 Hz, ArH-5), 7.62 (1H, td, J = 8.0 and 1.2 Hz, ArH-7), 7.78 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.78 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.15 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 337 (M + 1, 100).

4-(N-cyclopropyl)amino-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)aminoquinazoline (4f)

Starting with 2-chloro-4-(N-cyclopropyl)aminoquinazoline (3f) (215 mg, 0.98 mmol) and 4-methoxy aniline (184 mg, 1.49 mmol) to produce 103 mg of 4f in 33% yield, faint yellow solid, mp 192~194 °C; 1H NMR (CDCl3) δ ppm 0.94–0.99 (4H, m, CH2×2), 1.64 (1H, m, CH), 3.82 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.87 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.21 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-6), 7.42 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.56 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 7.65 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 8.02 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 10.27 (1H, s, NH), 13.26 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 307 (M + 1, 100).

Coupling reaction procedure for preparations of 4a, 5, 6, and 7 series

A mixture of a 4-substituted 2-chloroquinazoline (3) (1.0 equiv) and a para-substituted aniline or para-substituted N-methylaniline (1.05–1.5 equiv) in EtOH (2.5 mL) in a closed vial was heated under microwave irradiation at 150 °C for 15–25 min monitored by TLC until the reaction finished. The mixture was poured into water, and pH adjusted to 10 with NaHCO3. The solid crude product was collected, washed, and purified by flash column chromatography (gradient elution: MeOH/CH2Cl2, 0–5%) to give corresponding target compound.

4-(N-Cyclopentyl)amino-2-(4-methoxyphenyl)aminoquinazoline (4a)

Starting with 2-chloro-4-(N-cyclopentyl)aminoquinazoline (3a) (340 mg, 1.37 mmol) and 4-methoxyaniline (205 mg, 1.65 mmol) to produce 303 mg of 4a in 66% yield, faint yellow solid, mp 211~213 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.58 (2H, m, CH2), 1.77 (4H, m, CH2×2), 1.99 (2H, m, CH2), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 4.50 (1H, br, s, CH), 7.01 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.44 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-6), 7.48 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.54 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.81(H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 8.51 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.39 (1H, br, NH), 10.34 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 335 (M + 1, 100).

4-(N-Cyclopentyl)amino-2-(N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)aminoquinazoline (5a)

Starting with 3a (260 mg, 0.95 mmol) and 4-methoxy-N-methylaniline (160 mg, 1.16 mmol) to produce 270 mg of 5a in 82% yield, white solid, mp 216–218 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.53 (2H, m, CH2), 1.72 (4H, m, CH2 ×2), 1.93 (2H, m, CH2), 3.57 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.82 (3H, s, OCH3), 4.33 (1H, f, J = 7.2 Hz, CH), 7.09 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.42 (1H, t, J = 8.0, ArH-6), 7.43 (3H, m, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.78 (2H, m, ArH-5, 7), 8.51 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.36 (1H, br, NH); MS m/z (%) 349 (M + 1, 100), 281 (M 67, 70).

4-(3-Hydroxypropyl)amino-2-((N-(4-methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)aminoquinazoline (5b)

Starting with 3b (160 mg, 0.67 mmol) and N-methyl-4-methoxyaniline (112 mg, 0.81 mmol) to produce 165 mg of 5b in 73% yield, white solid, mp 188~190 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.75 (2H, m, CH2), 3.35–3.43 (4H, m, CH2×2), 3.56 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.82 (3H, s, OCH3), 4.60 (1H, s, OH), 7.09 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.43 (1H, m, ArH-6), 4,45 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.76 (2H, m, ArH-5, 7), 8.37 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.79 (1H, br, NH); MS m/z (%) 339 (M + 1, 100).

2-(N-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)amino-4-propylaminoquinazoline (5c)

Starting with 3c (240 mg, 1.08 mmol) and 4-methoxy-N-methylaniline (180 mg, 1.31 mmol) to produce 270 mg of 5c in 86% yield, white solid, mp 191~193 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 0.84 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH3), 1.58 (2H, m, CH2), 3.39 (2H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, NCH2,), 3.57 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.82 (3H, s, OCH3), 7.09 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.42 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.43 (1H, t, J = 8.0, ArH-6), 7.76 (2H, m, ArH-7,5), 8.40 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.87 (1H, br, NH); MS m/z (%) 322 (M + 1, 100).

2-(N-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)amino-4-methylaminoquinazoline (5d)

Starting with 3d (185 mg, 0.96 mmol) and 4-methoxy-N-methylaniline (160 mg, 1.16 mmol) to produce 214 mg of 5d in 76% yield, white solid, mp 204~206 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.02 (3H, br. s, NCH3), 3.58 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.83 (3H, s, OCH3), 7.11 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.43 (1H, m, ArH-6), 7.44 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.77 (2H, m, ArH-5, 7), 8.37 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.91 (1H, br, NH); MS m/z (%) 295 (M + 1, 100).

2-(N-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)amino-4-(N-morpholino)quinazoline (5e)

Starting with 3e (124 mg, 0.52 mmol) and 4-methoxy-N-methylaniline (75 mg, 0.55 mmol) to produce 138 mg of 5e in 80% yield, white solid, mp 143–145°C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.48 (4H, J = 4.2 Hz, NCH2×2), 3.48 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.69 (4H, t, J = 4.2 Hz, OCH2×2), 3.78 (3H, s, OCH3), 6.92 (2H, d, J = 8.8, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.13 (1H, td, J = 8.0 and 1.2 Hz, ArH-6), 7.27 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.41 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.57 (1H, td, J = 8.0 and 1.2 Hz, ArH-7), 7.77 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8); MS m/z (%) 350 (M + 1, 30), 321 (M − 29, 100).

2-(N-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-N-methyl)amino-4-(N-((tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)methyl)aminoqui nazoline (5g)

Starting with 2-chloro-4-(N-((tetrahydro-2H-pyran-4-yl)methyl) aminoquinazolin (3g) (138 mg, 0.50 mmol) and 4-methoxy-N-methylaniline (75 mg, 0.55 mmol) to produce 153 mg of 5g in 81% yield, white solid, mp 165–167°C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.06 (2H, m, CH2), 1.36 (2H, m, CH2), 1.74 (1H, m, CH), 3.07 (2H, t, J = 6.0 Hz, NCH2), 3.15 (2H, t, J = 10.0 Hz, CH2O), 3.44 (3H, s, NCH3), 3.75 (3H, s, OCH3), 3.79 (2H, m, CH2O), 6.92 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.07 (1H, td, J = 8.0 and 1.2, ArH-6), 7.25 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.31 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.50 (1H, td, J = 8.0 and 1.2 Hz, ArH-7), 7.97 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 8.03 (1H, t, J = 6.0 Hz, NH); MS m/z 379 (M + 1, 100).

2-(4-Cyanophenyl)amino-4-(N-cyclopentyl)aminoquinazoline (6a)

Starting with 3a (249 mg, 1.01 mmol) and 4-cyanoaniline (125 mg, 1.10 mmol) to produce 245 mg of 6a in 74 % yield, white solid, mp 218~220 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.63 (2H, m, CH2), 1.79 (4H, m, CH2×2), 2.05 (2H, m, CH2), 4.54 (1H, f, J = 7.2 Hz, CH), 7.51 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-6), 7.59 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.86 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.90 (1H, m, ArH-7), 7.91 (3H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 8.55 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.59 and 10.95 (each 1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 330 (M + 1, 100).

2-(4-Aminophenyl)amino-4-(N-cyclopentyl)aminoquinazoline (6b)

Starting with 3a (250 mg, 1.01 mmol) and benzene-1,4-diamine (123 mg, 1.13 mmol) to produce 220 mg of 6b in 69% yield, yellow solid, mp 223~225 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.57 (2H, m, CH2), 1.72 (4H, m, CH2×2), 2.00 (2H, m, CH2), 4.51 (1H, br, CH), 6.64 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.18 (2H, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.40 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-6), 7.54 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.77 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 8.46 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.25 (1H, br, NH), 10.05 (1H, br, NH); MS m/z (%) 320 (M + 1, 100), 252 (M − 67, 85).

4-(N-Cyclopentyl)amino-2-(4-fluorophenyl)aminoquinazoline (6c)

Starting with 3a (245 mg, 0.99 mmol) and 4-fluoroaniline (140 mg, 1.15 mmol) to produce 315 mg of 6c in 98% yield, white solid, mp 208~210 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.58 (2H, m, CH2), 1.76 (4H, m, CH2×2), 1.99 (2H, m, CH2), 4.47 (1H, m, CH), 7.30 (2H, t, JH, F = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.46 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-6), 7.56 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.62 (2H, dd, JH, F = 8.4 and 4.2 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.83 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 8.54 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.48 (1H, s, NH), 10.53 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 323 (M + 1, 100), 255 (M − 67, 97).

4-(N-Cyclopentyl)amino-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)aminoquinazoline (6d)

Starting with 3a (255 mg, 1.03 mmol) and 4-aminophenol (120 mg, 1.10 mmol) to produce 269 mg of 6d in 83% yield, light yellow solid, mp 169~171 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.57 (2H, m, CH2), 1.73 (4H, m, CH2×2), 2.00 (2H, m, CH2), 4.50 (1H, br, CH), 6.81 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.38 (3H, J = 8.0 z, ArH-2′, 6′ and ArH-6), 7.51 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.75 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 8.42 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.06 (1H, br, NH), 9.51 (1H, br, OH), 10.05 (1H, br, NH); MS m/z (%) 321 (M + 1, 90), 253 (M − 67, 100).

2-(4-Carboxyphenyl)amino-4-(N-cyclopentyl)aminoquinazoline (6e)

Starting with 3a (250 mg, 1.01 mmol) and 4-aminobenzoic acid (151 mg, 1.10 mmol) to produce 240 mg of 6e in 81% yield, white solid, mp 302~304 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.63 (2H, m, CH2), 1.79 (4H, m, CH2×2), 2.05 (2H, m, CH2), 4.57 (1H, f, J = 6.4 Hz, CH), 7.50 (1H, td, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-6), 7.57 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.79 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.86 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 7.99 (2H, d, J = 8.8 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 8.53 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.50 (1H, s, NH), 10.79 (1H, s, NH), 12.90 (1H, s, COOH); MS m/z (%) 349 (M + 1, 100).

2-(4-Cyanophenyl)amino-4-((3-hydroxypropyl)amino)quinazoline (7a)

Starting with 3b (241 mg, 1.01 mmol) and 4-cyanoaniline (125 mg, 1.05 mmol) to produce 48 mg of 7a in 34 % yield, white solid, mp 177~179 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.84 (2H, f, J = 6.0 Hz, CH2), 3.54 (2H, t, J = 6.0 Hz, NCH2), 3.70 (2H, m, OCH2), 4.62 (1H, br, OH), 7.51 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, H-6), 7.59 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.85 (1H, m, ArH-7), 7.87 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.90 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 8.40 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 10.05 (1H, s, NH), 10.91 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 320 (M + 1, 100).

2-(4-Aminophenyl)amino-4-((3-hydroxypropyl)aminoquinazoline (7b)

Starting with 3b (240 mg, 1.01 mmol) and benzene-1,4-diamine (120 mg, 1.10 mmol) to produce 196 mg of 7b in 63% yield, faint yellow, mp 274~276 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.81 (2H, m, CH2), 3.50 (2H, m, CH2), 3.61 (2H, m, CH2), 4.63 (1H, br, OH), 6.63 (2H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.18 (2H, br, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.41 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-6), 7.56 (1H, br. ArH-5), 7.77 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 8.31 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.58 (1H, br, NH), 10.02 (1H, br, NH); MS m/z (%) 310 (M + 1, 100).

2-(4-Fluorophenyl)amino-4-(3-hydroxypropyl)aminoquinazoline (7c)

Starting with 3b (237 mg, 1.00 mmol) and 4-fluoroaniline (133 mg, 1.05 mmol) to produce 206 mg of 7c in 66% yield, white solid, mp 185~187 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 1.80 (2H, f, J = 6.4 Hz, CH2), 3.49 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, CH2), 3.61 (2H, t, J = 6.4 Hz, CH2), 4.65 (1H, br, OH), 7.28 (2H, t, JH, F = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.47 (1H, td, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-6), 7.57 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.64 (2H, dd, JH, F = 8.4 and 4.2 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.83 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 8.36 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.85 (1H, br, NH), 10.42 (1H, br, NH); MS m/z (%) 313 (M + 1, 100).

4-Propylamino-2-(4-fluorophenyl)aminoquinazoline (7d)

Starting with 3c (133 mg, 0.60 mmol) and 4-fluoroaniline (75 mg, 0.67 mmol) to produce 120 mg of 7d in 67% yield, faint yellow solid, mp 202~204 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 0.91 (3H, t, J = 7.2 Hz, CH3), 1.65 (2H, six, J = 7.2 Hz, CH2), 3.48 (2H, m, CH2), 7.28 (2H, t, JH, F = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.46 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-6), 7.56 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.62 (2H, dd, JH,F = 8.4 and 4.2 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.82 (1H, t, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 8.39 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 9.87 (1H, br, NH), 10.44 (1H, br, NH); MS m/z (%) 297 (M + 1, 100).

2-(4-Fluorophenyl)amino-4-(N-morpholino)quinazoline (7e)

Starting with 3e (85 mg, 0.34 mmol) and 4-fluoroaniline (45 mg, 0.41 mmol) to produce 86 mg of 7e in 78% yield, white solid, mp 223~225 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.67 (4H, t, J = 4.2 Hz, 2 × NCH2), 3.81 (4H, t, J = 4.2 Hz, 2 × OCH2), 7.13 (2H, t, JH, F = 8.4 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.22 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-6), 7.54 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-5), 7.64(1H, dd, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-7), 7.86 (1H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-8), 7.91 (2H, dd, JH,F = 8.4 and 4.2 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 9.39 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 325 (M + 1, 100).

2-(4-Aminophenyl)amino-4-(N-morpholino)quinazoline (7f)

Starting with 3e (125 mg, 0.50 mmol) and benzene-1,4-diamine (60 mg, 0.57 mmol) to produce 152 mg of 7f in 94% yield, white solid, mp 195~197 °C; 1H NMR δ ppm 3.59 (4H, t, J = 4.0 Hz, 2 × NCH2), 3.80 (4H, t, J = 4.0 Hz, OCH2 ×2), 4.76 (2H, br, NH2), 6.52 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-3′, 5′), 7.13 (1H, t, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-6), 7.42 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-5), 7.46 (2H, d, J = 8.0 Hz, ArH-2′, 6′), 7.57 (1H, t, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-7), 7.79 (1H, d, J = 8.4 Hz, ArH-8), 8.83 (1H, s, NH); MS m/z (%) 322 (M + 1, 100).

Mer Tyrosine Kinase assay11

Inhibition of Mer kinase by a test compound was measured in the Microfluidic Capillary Electrophoresis (MCE) assay. This activity assay was performed in a 384-well, polypropylene microplate (Greiner BioOne, Monroe, NC) in a final volume of 50 µL in 50 mM Hepes, pH 7.4 containing 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.1% Triton X-100, 10 mM MgCl2 and ATP at 27 µM for the enzyme. All reactions were terminated by addition of 50 µL of 70 mM EDTA. Phosphorylated and unphosphorylated substrate peptides (EFPIYDFLPAKKK-CONH2 for Mer TK) were separated following a 180 min incubation on a Caliper LabChip EZ Reader II equipped with a 12-sipper chip in separation buffer supplemented with CR-8 and analyzed using EZ Reader software (Caliper Life Sciences; Hopkinton, MA). The assay conditions for MCE assays and screening against 72 kinases are described in Supporting Information (SI).

Antiproliferative activity in cellular assays

According to procedures described previously,20–22 target compounds were assayed by using the SRB method with a HTCL panel, included human lung carcinoma (A-549), epidermoid carcinoma of the nasopharynx (KB), P-gp-expressing epidermoid carcinoma of the nasopharynx (KBvin), and prostate cancer (DU145). Whereas, MTT method was used to evaluate antitumor activity in human myelogenous leukemia (MV4-11) cell line. The potency of each compound was expressed as GI50 value, which represents the molar drug concentration required to cause 50% tumor cell growth inhibition. All data represent at least three independent experiments performed in duplicate.

Aqueous Solubility Determination

Solubility was measured separately at pH 7.4 by using an HPLC-UV method. Test compounds were initially dissolved in DMSO at 10 mg/mL. Ten microliters of this stock solution were spiked into either pH 7.4 phosphate buffer (1.0 mL) with the final DMSO concentration being 1%. The mixture was stirred for 4 h at room temperature, and then concentrated at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The saturated supernatants were transferred to other vials for analysis by HPLC-UV and detected at 254 nm. Each sample was performed in triplicate. For quantification, a model 1200 HPLC-UV (Agilent) system was used with an Agilent Eclipse XDB-C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 5 m) and gradient elution of methanol (MeOH) in water, starting with 60% of MeOH, which was linearly increased up to 80% over 10 min, then slowly increased up to 90% over 15 min. The flow rate was 1.0 mL/min, and injection volume was 15 µL. Aqueous concentration was determined by comparison of the peak area of the saturated solution with a standard curve plotted as peak area versus known concentrations, which were prepared by solutions of test compound in acetonitrile (ACN) at 50 µg/mL, 25 µg/mL, 12.5 µg/mL, 3.13 µg/mL, 0.78 µg/mL, and 0.20 µg/mL.

Log P Measurement

Using the same DMSO stock solution (10 mg/mL) as above, 10 µL of this solution was added into n-octanol (0.6 mL) and water (0.6 mL). The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h and then left to stand overnight. Each solution (ca. 0.2 mL) from two phases was transferred respectively into other vials for HPLC analysis. The instrument and conditions were the same as those for solubility determination. Log P value was calculated by the peak area ratios in n-octane and in water (log P = log (Soct/Swater).

Molecular Modeling

All molecular modeling studies were performed with Discovery Studio 3.0 (Accelrys, San Diego, USA). The crystal structure of Mer kinase in complex with UNC569 (PDB code: 3TCP) was downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb) for use in the modeling study. Flexible Docking was used to evaluate and predict in silico binding free energy of the inhibitors and for automated docking. The protein protocol was prepared by several operations, including standardization of atom names, insertion of missing atoms in residues and removal of alternate conformations, insertion of missing loop regions based on SEQRES data, optimization of short and medium size loop regions with the Looper algorithm, minimization of remaining loop regions, calculation of pK, and protonation of the structure. The protein model was typed with the CHARMM force field. A binding sphere with a radius of 8.0 Å was defined through the original ligand (UNC569) as the binding site for the study. The docking protocol employed total ligand and the side chain of amino acids Leu671, Pro672, Phe673, Met674, Asp678, Arg727 and Asn728 flexibility, and the final ligand conformations were determined by the simulated annealing molecular dynamics search method set to a variable number of trial runs. Docked ligand 4b was further refined using in situ ligand minimization with the Smart Minimizer algorithm by standard parameters. The implicit solvent model of Generalized Born with Molecular Volume (GBMV) was also used to calculate the binding energies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Mer kinase screening assay data were provided by Prof. William P. Janzen, Center for Integrative Chemical Biology and Drug Discovery, Eshelman School of Pharmacy, UNC-CH. This investigation was supported by Grants 81120108022 from the Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) awarded to Dr. Lan Xie and NIH Grant CA177584 from the National Cancer Institute awarded to Dr. K. H. Lee. This study was also supported in part by the Taiwan Department of Health, China Medical University Hospital Cancer Research Center of Excellence (DOH100-TD-C-111- 005).

Abbreviations

- ALL

acute lymphocytic leukaemia

- ADMET

absorption, distribution, metabolism, elimination and toxicity

- A549

human lung cancer cell line

- DU145

prostate cancer cell line

- GI50

effective concentration for 50% cell growth inhibition

- HTCL

human tumor cell lines

- IC50

effective concentration that inhibits 50% Mer tyrosine kinase

- K562

human chronic myelogenous leukemia cell line

- KB

nasopharyngeal carcinoma cell line

- KB-vin

vincritstine-resistant KB subline cell line

- Mer TK

Mer tyrosine kinase

- MV4-11

acute leukemia cell line

- PDB

protein data base

- SAR

structure-activity relationship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Linger RMA, DeRyckere D, Brandao L, Sawczyn KK, Jacobsen KM, Liang X, Keating AK, Graham DK. Blood. 2009;114:2678–2687. [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Leary M, Krailo M, Anderson JR, Reaman GH. Seminars in Oncology. 2008;35:484–493. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salzer WL, Devidas M, Carroll WL, Winick N, Pullen J, Hunger SP, Camitta BA. Leukemia. 2009;24:355–370. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schultz KR, Bowman WP, Aledo A, Slayton WB, Sather H, Devidas M, Wang C, Davies SM, Gaynon PS, Trigg M, Rutledge R, Burden L, Jorstad D, Carroll A, Heerema NA, Winick N, Borowitz MJ, Hunger SP, Carroll WL, Camitta B. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2009;27:5175–5181. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guttridge KL, Luft JC, Dawson TL. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277(27):24057–24066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112086200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham DK, Salzberg DB, Kurtzberg J, Sather S, Matsushima GK, Keating AK, Liang X, Lovell MA, Williams SA, Dawson TL, Schell MJ, Anwar AA, Snodgrass HR, Earp HS. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2662–2669. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keating AK, Salzberg DB, Sather S, Liang X, Nickoloff S, Anwar A, Deryckere D, Hill K, Joung D, Sawczyn KK, Park J, Curran-Everett D, McGavran L, Meltesen L, Gore L, Johnson GL, Graham DK. Oncogene. 2006;25:6092–6100. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linger RMA, Keating AK, Earp HS, Graham DK. Advances in Cancer Research. 2008:35–83. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(08)00002-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linger RMA, Keating AK, Earp HS, Graham DK. Expert Opin. Ther. Tatgets. 2010;14(10):1073–1990. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2010.515980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang X, Finerty P, Jr, Walker JR, Butler-Cole C, Vedadi M, Schapira M, Parker SA, Turk BE, Thompson DA, DhePaganon S. J. Struct. Biol. 2009;165:88–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Yang C, Simpson C, DeRyckere D, Deusen AV, Miley MJ, Kireev D, Norris-Drouin J, Sather S, Hunter D, Korboukh VK, Patel HS, Janzen WB, Machius M, Johnson GL, Earp HS, Graham DK, Frye SV, Wang X. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;3:129–134. doi: 10.1021/ml200239k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W, Zhang D, Stashko MA, DeRyckere D, Hunter D, Kireev D, Miley MJ, Cummings C, Lee M, Norris-Drouin J, Stewart WM, Sather S, Zhou Y, Kirkpatrick G, Machius M, Janzen WP, Earp HS, Graham DK, Frye SV, Wang X. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:9683–9692. doi: 10.1021/jm401387j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, McIver AL, Stashko MA, DeRyckere D, Branchford BR, Hunter D, Kireev D, Miley MJ, Norris-Drouin J, Stewart WM, Lee M, Sather S, Zhou Y, Di Paola JA, Machius M, Janzen WP, Earp HS, Graham DK, Frye SV, Wang X. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:9693–9700. doi: 10.1021/jm4013888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang XF, Tian XT, Ohkoshi E, Qin B, Liu YN, Wu PC, Hung HY, Hour MJ, Qian K, Huang R, Bastow KF, Janzen WP, Jin J, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee KH, Xie L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;22:6224–6228. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang XF, Wang SB, Ohkoshi E, Wang LT, Hamel E, Qian K, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee KH, Xie L. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013;67:196–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2013.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang XF, Guan F, Ohkoshi E, Guo W, Wang L, Zhu DQ, Wang SB, Wang LT, Hamel E, Yang D, Li L, Qian K, Morris-Natschke SL, Yuan S, Lee KH, Xie L. J. Med. Chem. 2014;57:1390–1402. doi: 10.1021/jm4016526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang SB, Wang XF, Qin B, Ohkoshi E, Hsieh KY, Hamel E, Cui MT, Zhu DQ, Goto M, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee KH, Xie L. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2015;23:5740–5747. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smits RA, de Esch IJP, Zuiderveld OP, Broeker J, Sansuk K, Guaita E, Coruzzi G, Adami M, Haaksma E, Leurs R. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:7855–7865. doi: 10.1021/jm800876b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun LQ, Zhu L, Qian K, Qin B, Huang L, Chen CH, Lee KH, Xie L. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:7219–7229. doi: 10.1021/jm3007678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boyd MR. Status of the NCI preclinical antitumor drug discovery screen. In: Devita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology Updates. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1989. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monks A, Scudiero D, Skehan P, Shoemaker R, Paull K, Vistica D, Hose C, Langley J, Cronise P, Vaigro-Wolff A, Gray-Goodrich M, Campbell H, Mayo J, Boyd M. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1991;83:757–766. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.11.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Houghton P, Fang R, Techatanawat I, Steventon G, Hylands PJ, Lee CC. Methods. 2007;42:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.