Abstract

Background: The goals of limb-sparing surgery in the setting of extremity malignancies are 2-fold: oncological clearance and the rehabilitation of function and aesthetics. Treatment success should be defined by the extent of restoration of the patient’s premorbid function for reintegration into society. Methods: We would like to report an unusual case of a patient with a chronically ankylosed elbow with joint invasion by basal cell carcinoma which resulted from malignant transformation of an overlying, long-standing wound due to inadequately treated septic arthritis from his childhood years. Results: Following R0 resection, upper limb shortening and compression plate elbow arthrodesis were performed with the aim of restoring the degree of upper limb function that the patient had been accustomed to preoperatively. The resultant circumferential defect was then closed with a contralateral, free muscle-sparing latissimus dorsi flap. Conclusions: Functional preservation may therefore be more important than the mere restoration of anatomical defects in these especially challenging situations.

Keywords: upper extremity, limb salvage, elbow, arthrodesis, free flap

Introduction

The management of extremity malignancies has traditionally been wide resection and when necessary, amputation. With a multidisciplinary approach, limb salvage and functional reconstruction have become the treatment of choice because previous studies have shown comparable survival rates and an improved quality of life when compared with amputation.2 This has largely come about due to improvements in microsurgical techniques which have enabled the transfer of vascularized tissues, including bone, tendon, muscle, nerve, and skin, especially when major defects are anticipated. In contrast, plate-only arthrodesis of the wrist8 and shoulder3 after tumor resection has been reported previously, but such joint fusion of the elbow has not been described in the oncological setting because it remains largely a salvage procedure with much limitation in function that can be achieved.6 We would like to report a case of elbow reconstruction using a combination of both compression plate arthrodesis after limb shortening and microvascular free flap coverage for the circumferential defect after resection with successful restoration of the patient’s premorbid upper limb function.

Case Report

A 68-year-old, right-hand dominant man presented with an ankylosed right elbow that had a fixed-flexion deformity of approximately 65° without any active or passive range of joint motion. There was also a 4.4×3.5-cm fungating and discharging soft-tissue mass over the posterolateral aspect of the right elbow suspicious for malignancy. Previously at the age of 13 years, the patient had developed septic arthritis which required open arthrotomy and joint washout following a supracondylar fracture of the right humerus. Swabs were taken from the wound discharge and sent for bacterial cultures, which grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus, confirming the presence of concomitant infection. Initial workup, including blood tests and x-rays, was inconclusive, but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a deep and extensive invasive component, which could not be differentiated from the destruction and scarring from his childhood injury (Figure 1). Open wedge biopsy was then performed with a histopathology of invasive basal cell carcinoma (BCC; nodular subtype) reported (Figure 2), and further preoperative positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET-CT) imaging was negative for metastases (Figure 1). The patient was subsequently counseled and informed consent obtained for a planned wide resection and reconstruction with a fibular autograft, plate construct, and free tissue transfer for defect coverage.

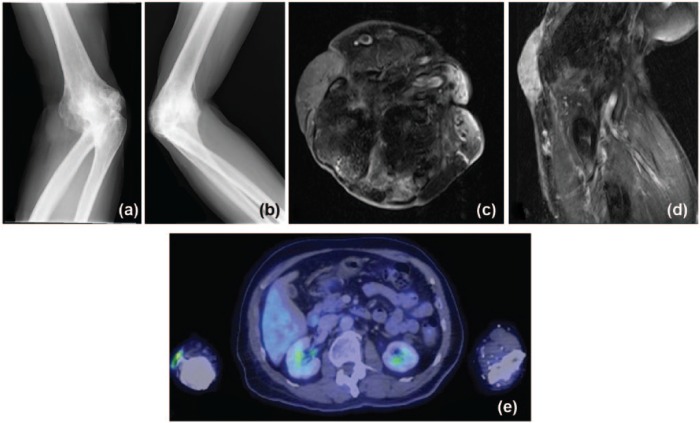

Figure 1.

Preoperative imaging studies: (a, b) X-rays showed marked cortical irregularities with sclerosis of articulating bones, disorganization and arthrodesis of the proximal radioulnar and radiocapitellar joints; (c, d) T1-weighted MRI with contrast revealed almost complete ankylosis of the elbow with hypointensity suggestive of calcification at the radiocapitellar joint, subcutaneous soft-tissue edema over the olecranon, and diffuse skin thickening with a heterogeneous slightly hyperintense and enhancing lesion at the lateral aspect of the elbow; (e) PET-CT was only significant for focal FDG uptake in the lateral aspect of the right elbow.

Note. MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET-CT, positron emission tomography–computed tomography; FDG, fluorodeoxyglucose.

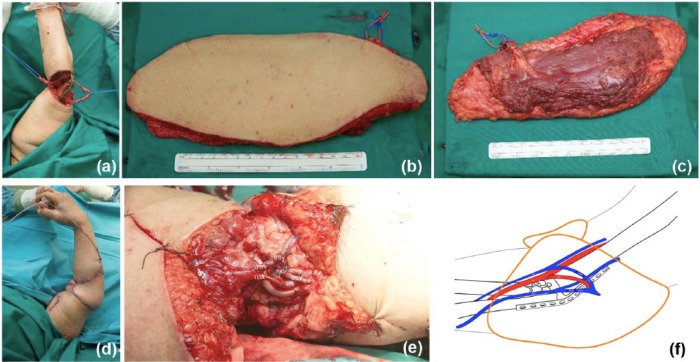

Figure 2.

(a) Preoperative clinical view of lesion over posterolateral aspect of right ankylosed elbow. (b) Histopathology demonstrates peripheral palisading of the tumor cells with stromal retraction clefting characteristic of basal cell carcinoma (hematoxylin-eosin, original magnification ×200).

Intraoperatively however, the skin overlying the elbow was contracted with involvement of the joint capsule; the radial and ulnar nerves were also scarred down. R0 resection with clear margins on the intraoperative frozen section was achieved via en bloc resection of the entire elbow joint (12 cm superoinferiorly × 10 cm mediolaterally × 8 cm anteroposteriorly), including a portion of the distal humerus, the proximal radius and ulna, and the overlying soft tissues. At this point, the resection defect was circumferential with exposure of the radial and ulnar nerves, and transected cephalic and basilic veins (Figure 3). An on-table decision was taken to proceed with elbow arthrodesis, and this was achieved after shortening of the upper limb (about 9 cm in total) with further osteotomies using an oscillating saw and osteotomes until there were raw bleeding bone surfaces with maximal contact for internal osteosynthesis using a 4.5-mm titanium locking compression plate to obtain a fusion angle at about 65° flexion (same as the preoperative fixed-flexion deformity) between the distal humerus and proximal ulna. The aim of this was to restore the same degree of function that the patient had been accustomed to in the last 55 years. The proximal radius was also shortened, and these pieces of bone were salvaged as an on-lay autograft around the planned fusion site.

Figure 3.

Postexcision circumferential defect including exposure of the radial and ulnar nerves, and transected basilic and cephalic veins (not shown).

The short saphenous vein was then harvested for interpositional vein grafting of the transected cephalic and basilic veins. Next, a contralateral, muscle-sparing free latissimus dorsi flap measuring 24×10 cm was harvested and transferred to the right elbow defect (Figure 4). The thoracodorsal artery was anastomosed end to side with the brachial artery; the thoracodorsal vein and a branch of the serratus anterior vein were both anastomosed end to end with branches of the cephalic and basilic veins, respectively (Figure 4), via the short saphenous vein grafts. The flap was then inset in a 360° wrap-around manner and the wound closed over suction drains.

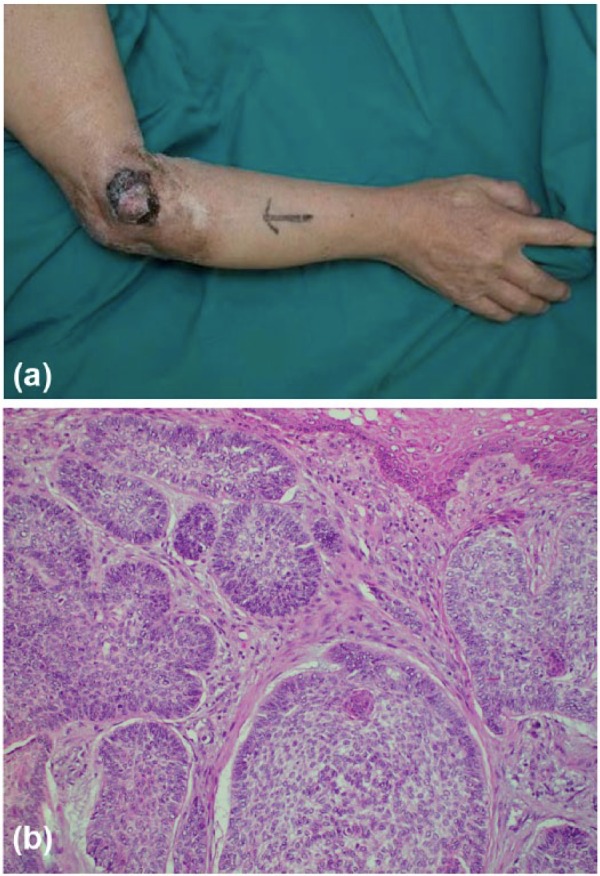

Figure 4.

(a) Postexcision circumferential defect with exposure of the radial and ulnar nerves and plate after limb shortening and joint arthrodesis; (b, c) harvest of a 24×10-cm muscle-sparing free latissimus dorsi flap; (d) flap inset in a 360° wrap-around fashion; and microsurgical anastomosis (e) intraoperative and (f) schematic views.

Note. TDA was anastomosed end to side to the BA; the TDV and a branch of the SAV were both anastomosed end to end to the CV and a branch of the BV, respectively, via interpositional SSV grafts. TDA, thoracodorsal artery; BA, brachial artery; TDV, thoracodorsal vein; SAV, serratus anterior vein; CV, cephalic vein; BV, basilic vein; SSV, short saphenous vein.

The patient’s postoperative course was otherwise unremarkable, and he was discharged after 19 days. A specially designed cast was used to splint the reconstructed upper limb from the arm to the wrist with a window at the elbow (recipient site) for flap monitoring. This had to be refashioned a couple of times during the course of his follow-up due to cast migration. Bone healing with obvious evidence of callous formation was seen on x-ray by 9 months postoperative (Figure 5). The patient was last seen at 23 months after surgery and has undergone secondary flap debulking procedures twice at 11 and 19 months. There have been no symptoms of ulnar, median, or radial nerve compression or chronic pain. Hand function (motor and sensory) was also largely preserved because the median nerve was not resected intraoperatively, but it was not as strong or dexterous as before. This is due to the operative sequelae of partial proximal loss and detachment of the flexor and extensor muscle origins off the distal humerus and proximal radius and ulna (Figure 6) where margins were taken and limb shortening performed; forearm muscle function was still possible because part of the muscle originates from the interosseous membrane and radial and ulnar shafts which were all largely preserved. The patient is otherwise very satisfied with the outcome of his surgery with no significant difference in 2-point discriminatory sensation compared with before surgery; functionally, though he was previously only able to feed himself using cutlery before the surgery, he was now able to reach to his mouth with his hand after the limb-shortening procedure.

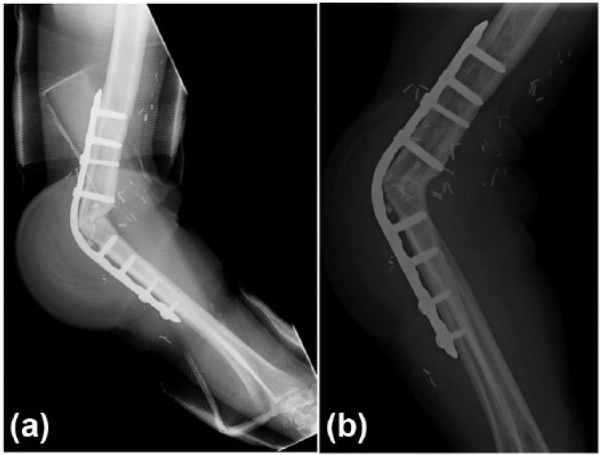

Figure 5.

Postoperative x-rays: (a) at 9 months showing early signs of callous formation; (b) at 23 months follow-up with evidence of bony union across the site of joint arthrodesis.

Figure 6.

Functional preservation achieved with satisfactory restoration of the patient’s preoperative upper limb to its preoperative state.

Note. Clinical deformity seen is due to morbidity arising from oncological resection leading to partial loss of flexor and extensor muscle origins; satisfactory regain of hand function was achieved with hand therapy.

Discussion

Malignant degeneration of a chronic, nonhealing wound is known as Majorlin’s ulcer and is usually in the form of squamous cell carcinoma. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of Majorlin’s ulcer arising from BCC with an invasive component into the joint. There has only been one similar case in the literature reported by Kopp et al, but this was due to a primary BCC, and their treatment plan consisted of 4 stages: excision and vacuum-assisted closure, re-excision to clear margins, surgical delay of a pedicled musculocutaneous latissimus dorsi flap measuring 18×23 cm, and flap division and transfer for wound coverage.5 The patient was eventually discharged after 42 days and reported to have a complete range of elbow motion but without any mention of specific details of upper limb function or follow-up period. In contrast, we adopted an approach similar to that for the treatment of extremity sarcomas in our patient by offering immediate functional reconstruction to hopefully achieve a quicker recovery time and reduce the overall number of surgical procedures and costs, which has been demonstrated by Mundinger et al to be a viable strategy especially when upper limb function is anticipated to be severely compromised following oncological resection as in this case.7 In addition, we were obliged to err on the side of caution in our case and to assume that the entire elbow joint was affected due to the combination of intraoperative local anatomy, as suggested by Anwar et al,1 and preoperative MRI findings as described previously. Taken together, we felt that wide excision of the elbow joint to include the periosteum and adjacent bone was necessary for adequate oncological clearance despite the large amount of bone loss involved; the final deep (and closest soft-tissue) margin reported was 2.5 cm without tumor involvement or evidence of bone or marrow infiltration.

In treating large bony defects with elbow arthrodesis, the choice of compression plate-only elbow arthrodesis for internal osteosynthesis in this instance requires further justification, especially when there are other reconstructive options available, such as a composite latissimus dorsi-rib flap,9 free vascularized fibula bone grafting in combination with prostheses,10 or even a total elbow arthroplasty. We rationalized our treatment approach based on (1) long-standing ankylosis of the elbow joint with a severely restricted range of motion due to long-term atrophy and contracture of the muscles controlling the joint which would therefore not add any function even with a total elbow arthroplasty that costs significantly more than a plate; instead, the patient had learnt to compensate with postural adjustments over the last 55 years prior to his presentation; (2) evidence of chronic infection in the site of BCC invasion that would pose a risk to local soft-tissue reconstruction especially when the patient’s skin and muscles were thin and atrophied, and this may, in turn, necessitate further revision surgeries in the event of nonunion or malunion and pathological fractures; (3) extensive bone and soft-tissue loss to an upper extremity that is already functionally limited, on top of the post-resection defect that did not have adequate bone stock for a regular total elbow arthroplasty; and (4) rigid plate fixation to allow skeletal stability for earlier functional rehabilitation to maximize clinical outcomes in a patient who is not anticipated to have full dynamic function restored. In addition, further shortening of the humerus before elbow arthrodesis also reduces the arm length to enable closer proximity to the body and mouth.

The soft-tissue coverage of the reconstructed elbow joint in this case also proved particularly challenging. A muscle-sparing harvest of the latissimus dorsi flap, where only a cuff of muscle was taken rather than in its entirety, was performed because it would otherwise be excessive for insetting into a circumferential elbow defect that required skin coverage that was both thin yet sturdy enough. The cuff of muscle also provided for dead space obliteration of the defect after resection and limb shortening, improved antibiotic delivery to help combat the existing chronic infection, and helped in withstanding the potential shearing forces from the compression plate posteriorly where the elbow is a pressure-prone area. Anteriorly, microvascular anastomosis of the flap at the antecubital fossa meant that the neurovascular structures were configured like a “bag of spaghetti” and were at a higher risk of compression and kinking during flap inset due to its bulkiness despite a muscle-sparing harvest, as well as the consequent tension during wound closure in a 360° wrap-around fashion. The location of the microanastomoses also proved to be a particular challenge during subsequent secondary debulking procedures. Finally, casting of the shortened limb and plated elbow is not without risk to the flap reconstruction due to possible cast migration and consequent flap compression and circulatory compromise.

Overall, treatment success in upper extremity oncologic reconstruction should be defined by the extent of restoration of the patient’s premorbid function for successful reintegration into society. Functional preservation as demonstrated in this case by the combination of elbow arthrodesis, a last resort but reliable technique, in combination with modern microsurgical methods for defect coverage, may therefore be more important than the mere restoration of anatomical defects in these especially challenging situations.4

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Junsiyuan Li, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Singapore General Hospital, and Dr Kesavan Sittampalam and Dr Timothy Tay, Department of Pathology, Singapore General Hospital, for their help and expertise with the preparation of this article.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: This study was approved by our institutional review board.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: Not applicable in the study.

Statement of Informed Consent: Informed consent (verbal) was obtained from the patient for this study.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Anwar U, Al Ghazal SK, Ahmad M, Sharpe DT. Horrifying basal cell carcinoma forearm lesion leading to shoulder disarticulation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:6e-9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bray PW, Bell RS, Bowen CV, Davis A, O’Sullivan B. Limb salvage surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy for soft tissue sarcomas of the forearm and hand. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22:495-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chun JM, Byeon HK. Shoulder arthrodesis with a reconstruction plate. Int Orthop. 2009;33:1025-1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Koller H, Kolb K, Assuncao A, Kolb W, Holz U. The fate of elbow arthrodesis: indications, techniques, and outcome in fourteen patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:293-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kopp J, Polykandriotis E, Loos B, et al. Giant rodent ulcer of the elbow requiring defect coverage by preconditioned latissimus dorsi pedicled myocutaneous flap following excision. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:252-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McAuliffe JA, Burkhalter WE, Ouellette EA, Carneiro RS. Compression plate arthrodesis of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992;74:300-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mundinger GS, Prucz RB, Frassica FJ, Deune EG. Concomitant upper extremity soft tissue sarcoma limb-sparing resection and functional reconstruction: assessment of outcomes and costs of surgery. Hand. 2014;9:196-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O’Bierne J, Boyer MI, Axelrod TS. Wrist arthrodesis using a dynamic compression plate. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1995;77:700-704. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ozer K, Toker S, Morgan S. The use of a combined rib-latissimus dorsi flap for elbow arthrodesis and soft-tissue coverage. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20:e9-e13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van Alphen NA, Houdek MT, Steinmann SS, Moran SL. Combined composite osteofasciocutaneous fibular free flap and radial head arthroplasty for reconstruction of the elbow joint. Microsurgery. 2014;34:475-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]