Abstract

Background and Purpose

Emergency Medical Services (EMS) routing of acute stroke patients to designated centers may increase the proportion of patients receiving care at facilities meeting national standards and augment recruitment for prehospital stroke research.

Methods

We analyzed consecutive patients enrolled within 2 hours of symptom onset in a prehospital stroke trial, before and after regional Los Angeles County Emergency Medical Services (EMS) implementation of preferentially routing acute stroke patients to Approved Stroke Centers (ASCs). From January 2005 to mid-November 2009, patients were transported to the nearest Emergency Department, while from mid-November 2009 to December 2012 patients were preferentially transported to first 9, and eventually 29, ASCs.

Results

There were 863 subjects enrolled before and 764 after EMS preferential routing, with implementation leading to an increase in the proportion cared for at an ASC from 10% to 91% (P<0.0001), with a slight decrease in paramedic on-scene to Emergency Department arrival time (34.5 minutes [SD 9.1] vs. 33.5 [SD 10.3], p=0.045). The effects of routing were immediate and included an increase in of proportion receiving ASC care (from 17% to 88%, p<0.001) and a greater number of enrolments (18.6% increase) when comparing 12 months before and after regional stroke system implementation.

Conclusions

The establishment of a regionalized EMS system of acute stroke care dramatically increased the proportion of acute stroke patients cared for at ASCs, from 1 in 10 to more than 9 in 10, with no clinically significant increase in prehospital care times, and enhanced recruitment of patients into a prehospital treatment trial.

Keywords: prehospital, stroke, emergency medical services, triage

INTRODUCTION

Clinical trials and observational studies demonstrate that acute stroke patients have better outcomes when cared for at designated acute stroke centers1, 2. Consequently, national guidelines from Emergency Medical Services (EMS) organizations and from the American Stroke Association have recommended that EMS systems preferentially route acute stroke patients to certified acute stroke centers known to be capable of rapidly and reliably delivering systematic stroke care.3, 4 By the end of 2010, in the United States, 17 states and several additional counties, covering 53% of the national population had legislation or regulation requiring EMS to set up regional systems of acute stroke care with preferential routing of early stroke patients to stroke center facilities.5, 6

However, during the rapid expansion of regionalized stroke care systems, formal studies of their effect on increasing access to stroke center care been sparse. In addition, prior studies have not investigated the impact of regionalized routing on recruitment of patients into prehospital stroke treatment trials. We studied the impact of preferential routing of patients to stroke centers on sites of care, prehospital transport times, and research recruitment in the most populous county in the United States.

METHODS

Data was obtained from the National Institute of Health Field Administration of Stroke Therapy-Magnesium (FAST-MAG) clinical trial,7 a phase 3 clinical trial of prehospital initiation of magnesium vs. placebo for likely stroke patients presenting within 2 hours from last known well time. The detailed methods of the FAST-MAG trial have been published.8, 9 Patients with likely stroke indicated by a positive Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS) and paramedic and physician-confirmed last known well time of within 2 hours were offered enrollment in the trial. The trial was conducted in Los Angeles County from 2005-2012 and in Orange County from 2010-2012. Cases entered into this study were confined to Los Angeles County. Los Angeles County has a population of 10 million racially and ethnically diverse inhabitants. The Los Angeles County Emergency Medical Services (EMS) system is the largest in the US, with 31 provider agencies, 238 paramedic ambulances, over 2,200 paramedics, and 69 adult receiving hospitals.

In response to national3, 4 and state10 recommendations, the deliberations of the LA County Stroke Task Force, and public stakeholder forums, the Los Angeles EMS Agency implemented a countywide stroke regional system of care on November 16, 2009. This regional policy was developed independently of the clinical trial and will continue to be implemented indefinitely. Before this date, paramedics transported presumptive stroke patients to the nearest adult Emergency Department. After this date, EMS preferentially routed presumptive stroke patients within 2 hours of last known well time directly to the nearest Approved Stroke Center (ASC). However, if paramedic ambulance transport time was more than 30 minutes, the patient was medically unstable, or the patient requested a preferred non-ASC facility, they were transported to the nearest or preferred medical facility, whether or not it was an ASC. To be designated as Approved Stroke Centers, receiving hospitals had to: 1) be certified as Primary Stroke Center (PSC) by The Joint Commission (or equivalent national body), 2) sign a letter of understanding indicating they would follow the policies required by LA EMS for ASCs, and 3) share pre-specified data on individual cases transported to their facility with LA EMS.

The implementation of the LA County EMS Regional Stroke System during the period of performance of the Field Administration of Stroke Therapy- Magnesium (FAST-MAG) clinical trial afforded a unique opportunity to analyze data collected before and after policy enactment. FAST-MAG was a phase 3, NIH-funded, randomized clinical trial assessing magnesium sulfate or placebo initiated by paramedics in the field within 2 hours of stroke onset being conducted throughout Los Angeles County.11 Entry criteria for FAST-MAG and selection criteria for routing to Approved Stroke Centers strongly overlapped. Both required patients to be identified as likely having acute stroke on a modified version of the Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen and to be within 2 hours of last known well time.12, 13 However, appropriate to a research trial, FAST-MAG had additional selection criteria, including absence of severe renal failure, absence of pre-stroke disability, and systolic blood pressure between 90-220.14

Data collected prospectively in FAST-MAG analyzed for this report included date of enrollment, destination hospital, last known well time (LKWT), time of paramedic arrival on scene, time of emergency department arrival, and final diagnosis (ischemic stroke, transient ischemic attack (TIA), intracranial hemorrhage (ICH), other). Neurologic deficit severity at the time of paramedic encounter was rated on the Los Angeles Motor Scale (LAMS).15 Additionally, ASC or non-ASC status of destination hospitals on enrollment dates was determined for all enrolled patients from January 2005 to December 2012. Launch of the EMS routing policy occurred in the middle of this period, on November 16, 2009. During the pre-routing period, 41 of the 69 adult ED receiving facilities in the County participated in the FAST-MAG trial, including all the medium and large stroke volume hospitals. At the initiation of the routing policy 9 of the 67 adult ED receiving facilities (two facilities closed) in the County were Approved Acute Stroke Centers. By December 2011, the number of ASCs increased to 24, and by trial end in December 2012 the number of ASCs increased to 29. Patients were considered brought to a non-Approved Stroke Center if they were transported to a hospital that never became or an ASC or were transported to a hospital that eventually became an ASC but before it acquired ASC status. Patients were considered brought to an ASC if they were transported to an ASC facility after it had acquired ASC status. All ASC hospitals in this study were certified as Primary Stroke Centers (PSC) by The Joint Commission (TJC). Although every certified PSC hospital eventually sought approval as an ASC, the dates of certification (by TJC) and designation (as an ASC) may have differed. For the purposes of these analyses we considered the date of ASC designation and not PSC certification, however there were no study cases presenting to a hospital achieving PSC certification but not ASC approval, and thus the terms ASC and PSC are used interchangeably in this study.

The impact of routing policy implementation upon the proportion of patients accessing Approved Stroke Centers was analyzed over the entire 8-year study period. In addition, to minimize the effects of secular changes in care processes, the effect of routing policy on use of tissue plasminogen activator and trial enrollment rate was examined in the narrower time band of the year before and one year after field triage policy start.

RESULTS

From January 2005 to December 2012 there were 1627 enrollments in Los Angeles County, 863 (53%) prior to and 764 (47%) after adoption of the countywide EMS routing protocol. In the immediate peri-adoption period, during the one year before routing 215 patients were enrolled and during the one year after 255, patients were enrolled. Clinical characteristics of patients enrolled before and after EMS routing are shown in Table 1, and did not differ.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics of before and after groups, including age, sex, LAMS score, time from LKW to arrival on scene, scene to door time.

| Overall FAST-MAG Study population | One year Pre and post | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Before (n=863) | After (n=764) | Significance (p) | Before (n=215) | After (n=255) | Significance (p) |

| Age (years, Mean, SD) | 69 (14) | 70 (14) | 0.162 | 68 (14) | 70 (14) | 0.239 |

| Female Gender N (%) | 366 (42%) | 325 (43%) | 0.958 | 88 (41%) | 102 (40%) | 0.838 |

| Race | 0.016 | 0.485 | ||||

| White | 692 (80%) | 568 (74%) | 175 (81%) | 198 (78%) | ||

| Black | 95 (11%) | 123 (16%) | 22 (10%) | 37 (12%) | ||

| Asian | 67 (8%) | 64 (8%) | 11 (5%) | 12 (5%) | ||

| Other | 9 (1%) | 9 (1%) | 7 (3%) | 7 (3%) | ||

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 200 (23%) | 191 (25%) | 0.397 | 55 (26%) | 66 (26%) | 0.921 |

| LAMS Score (median, IQR) | 3 (2-5) | 3 (1-5) | 0.664 | 3 (2-5) | 3 (1-5) | 0.664 |

| Final Diagnosis | 0.193 | 0.197 | ||||

| Cerebral Ischemia | 628 (73%) | 563 (74%) | 149 (69%) | 173 (68%) | ||

| ICH | 207 (24%) | 165 (22%) | 60 (28%) | 69(27%) | ||

| Other (i.e. stroke mimic) | 28 (3%) | 36 (5%) | 6 (3%) | 13 (5%) | ||

| Time from 911 call to paramedic on-scene (Minutes, mean [SD]) | 6.4 [3.1] | 7.4 [3.9] | <0.001 | 6.9 [3.4] | 6.5 [3.0] | 0.235 |

| Time on-scene to ED arrival (Minutes, median, [IQR]) | 33, [28-40] | 32, [27-39] | 0.045 | 32, [27-39] | 33, [28-41] | 0.270 |

| Intravenous TPA Administered (% of cerebral ischemia, N treated/N cerebral ischemia) | 29% (178/624) | 42% (230/547) | <0.001 | 33% (49/149) | 35% (60/173) | 0.832 |

| Transported to an Approved Stroke Center | 10%(90/863) | 91% (698/764) | <0.001 | 17% (37/215) | 88% (224/255) | <0.001 |

LAMS: Los Angeles Motor Score,15 LKWT: Las known well time, TPA: Tissue plasminogen activator

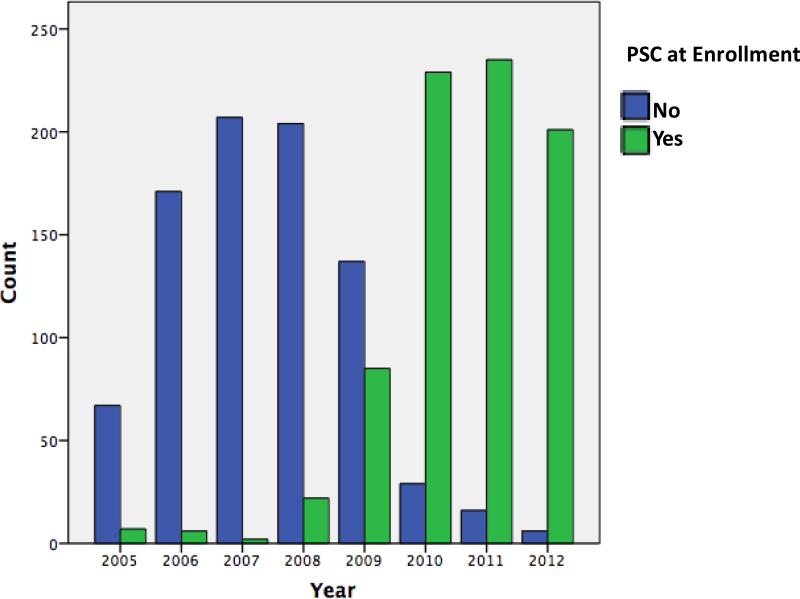

Figure 1 shows the number of enrolled acute likely stroke patients receiving care at PSC/ASCs throughout the course of the study. Overall, in the nearly 5 years prior to EMS routing, 90/863 (10%) patients were transported to a PSC. In contrast, in the slightly more than 3 years after EMS routing 698/764 (91%) patients were transported to a PSC (P<0.001). Prior to introduction of routing, in the years 2005-2008, there was minimal or no increase in the proportion of patients treated at PSCs. The start of routing in 2009 had a substantial immediate effect; with further increases in the PSC care proportion throughout 2010-2012 as more facilities became designated stroke centers. By the final year of the study, 2012, 201/207 (97%) of patients received initial care at a certified PSC. Over the entire study period, the introduction of preferential routing was not associated with an increase in the time interval from paramedic arrival on scene to ED arrival (scene to door time). Scene to door time actually slightly decreased from the pre-diversion to the diversion period, 34.5 min. (SD 9.1) vs. 33.5 (SD 10.3), p=0.045.

Figure 1.

Yearly count of subjects enrolled by destination hospital without (blue) or with (green) PSC certification

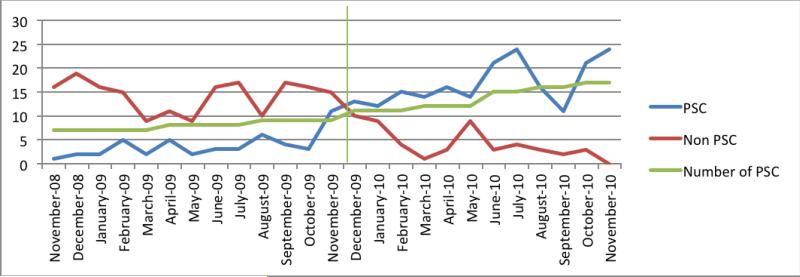

Figure 2 shows data from the focused analysis of the year immediately before and the year immediately after implementation of the EMS routing policy. During the baseline year, under the policy of transport to the nearest ED regardless of stroke center status, 215 subjects were enrolled in the field and transported to 44 receiving hospitals. In the post-intervention year, under the destination policy of preferential routing to stroke centers, 255 subjects were enrolled in the field and transported to 27 receiving hospitals. The percentage of subjects transported to Joint Commission-certified Primary Stroke Centers increased from 17% in the period prior to implementation to 88% following PSC diversion (P<0.0001, Figure 1). The mean monthly enrollment rate increased from 17.9 before to 21.2 after stroke center diversion. Time intervals from paramedic arrival on scene to patient arrival at the ED (scene to door times) during the before and after stroke center routing periods were similar, 33.6 (SD 9.7) minutes before vs.34.8 (SD 10.6) minutes after, p=0.221 in the focused two-year analyses. The number of patients who received intravenous TPA after ED arrival increased from 49 to 60, an increase of 22%, although the rates of TPA use among enrolled ischemic stroke patients did not differ (23% vs. 24%) in the two-year period encompassing policy change.

Figure 2.

Number of patients each month enrolled in FAST-MAG and brought by EMS to receiving hospitals certified or not certified as Primary Stroke Centers by the Joint Commission. The blue line traces enrollments with PSC destination hospitals whereas the red line traces non-PSC receiving facilities. The green line indicates the November 16, 2009 date of implementation of PSC diversion

DISCUSSION

Our findings demonstrate that regionalized systems of stroke care can have an immediate and profound effect on acute stroke care processes.16 Implementation of a prehospital routing system to Approved Stroke Centers in the most populous county in the United States resulted in an immediate and dramatic increase in the proportion of acute stroke patients cared for at certified Primary Stroke Centers. In the first year of implementation, the percentage of hyper-acute stroke patients (LKWT under 2 hours) cared for at Joint Commission-certified Primary Stroke Centers quintupled, from less than 20% to nearly 90% of eligible patients. The substantial increase in the proportion of patients cared for at certified PSCs is expected to have beneficial effects on clinical outcome based on prior clinical trials and observational studies. The systematic medical and nursing care provided at PSCs has been shown to improve outcomes for hemorrhagic patients and for ischemic stroke patients treated with lytics and treated with supportive care.2, 3, 17

In addition to improving access to stroke center care; implementation of EMS routing also drove a substantial increase in recruitment of patients into an NIH trial of a potential prehospital neuroprotective agent for stroke. In the one-year pre-intervention period, the FAST-MAG trial was active at 50 of the 69 receiving facilities in the County, accounting for over 80% of patient transports in the County. However, patients being transported to the remaining 19 smaller hospitals could not be offered trial enrollment. Since all Approved Stroke Centers in the county were also active trial sites, after system implementation more patients had trial facilities as their destination hospitals and could be offered trial enrollment. The Los Angeles experience is one of the first to demonstrate that regional systems of acute stroke can increase patient enrollment in studies of promising new therapies, an often envisaged potential benefit of care regionalization.18 Fewer destination hospitals receiving a greater share of acute stroke patients can lead to more efficiency in clinical trial planning and better focus of resources.

This study's findings confirm and extend prior reports of implementation of stroke centers in US urban regions. The pioneering system implementations in Houston and in two New York City boroughs were both associated with rapid and substantial increases in the proportion of patients cared for at designated facilities.19, 20 The current study demonstrates this effect in a larger EMS system using Joint Commission-certified, not locally certified, stroke centers and also uniquely shows a beneficial impact upon research recruitment.

This study has limitations. The population recruited into FAST-MAG is a subset of patients covered by the regional routing policy, rather than all patients. However, none of the exclusion criteria, such as renal failure, absence of a consent provider, or patient declination regarding trial participation, appear likely to confound analysis of routing impact. The study analyzed effects in the first 3 years after system implementation. At the end of this period 29 hospitals had become Approved Stroke Centers and joined the regional system. In subsequent years, several additional facilities have joined, as the regional system continued to mature. With more facilities, a few additional geographic pockets in our system with no available ASC were filled in, likely allowing even a greater proportion of patients to be transported to an Approved Stroke Center and further decreasing field transport times.

We conclude that the impact of EMS regional stroke care organization is immediate and profound, has the potential to improve patient outcomes, and can substantially enhance patient recruitment into prehospital clinical trials.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: Supported by NIH-NINDS Award U01 NS 44364

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration- URL: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov. Unique identifier: NCT00059332

Disclosures: David S. Liebeskind: Honoraria from Stryker and Covidien, research funding form the NIH

WORKS CITED

- 1.Audebert HJ, Schenkel J, Heuschmann PU, Bogdahn U, Haberl RL. Effects of the implementation of a telemedical stroke network: The telemedic pilot project for integrative stroke care (tempis) in bavaria, germany. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:742–748. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(06)70527-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Xian Y, Holloway RG, Chan PS, Noyes K, Shah MN, Ting HH, et al. Association between stroke center hospitalization for acute ischemic stroke and mortality. JAMA. 2011;305:373–380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acker JE, Pancioli AM, Crocco TJ, Eckstein MK, Jauch EC, Larrabee H, et al. Implementation strategies for emergency medical services within stroke systems of care. Stroke. 2007;38:3097–3115. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.186094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crocco TJ, Grotta JC, Jauch EC, Kasner SE, Kothari RU, Larmon BR, et al. Ems management of acute stroke—prehospital triage (resource document to naemsp position statement). Prehospital Emergency Care. 2007;11:313–317. doi: 10.1080/10903120701347844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song S, Saver JL. Growth of regional stroke systems of care in the united states in the first decade of the 21st century. Stroke. 2011;42:e340. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.657809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hanks N, Wen G, He S, Song S, Saver JL, Cen S, et al. Expansion of u.S. Emergency medical service routing for stroke care: 2000-2010. The western journal of emergency medicine. 2014;15:499–503. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2014.2.20388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saver JL, Starkman S, Eckstein M, Stratton S, Pratt F, Hamilton S, et al. Prehospital initiation of magnesium sulfate as neuroprotection for acute stroke. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:528–536. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1408827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saver JL, Starkman S, Eckstein M, Stratton S, Pratt F, Hamilton S, et al. Methodology of the field administration of stroke therapy - magnesium (fast-mag) phase 3 trial: Part 1 - rationale and general methods. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:215–219. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saver JL, Starkman S, Eckstein M, Stratton S, Pratt F, Hamilton S, et al. Methodology of the field administration of stroke therapy - magnesium (fast-mag) phase 3 trial: Part 2 - prehospital study methods. Int J Stroke. 2014;9:220–225. doi: 10.1111/ijs.12242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stroke Systems Work Group Recomendations for the establishment of an optimal system of acute stroke care for adults: A statewide plan for california. [7/13/15];California Department of Public Healt website. 2009 http://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/cvd/Pages/strokecare.aspx.

- 11.Sanossian N, Starkman S, Liebeskind DS, Ali LK, Restrepo L, Hamilton S, et al. Simultaneous ring voice-over-internet phone system enables rapid physician elicitation of explicit informed consent in prehospital stroke treatment trials. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:539–544. doi: 10.1159/000247596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kidwell CS, Saver JL, Schubert GB, Eckstein M, Starkman S. Design and retrospective analysis of the los angeles prehospital stroke screen (lapss). Prehospital Emergency Care. 1998;2:267–273. doi: 10.1080/10903129808958878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kidwell CS, Starkman S, Eckstein M, Weems K, Saver JL. Identifying stroke in the field : Prospective validation of the los angeles prehospital stroke screen (lapss). Stroke. 2000;31:71–76. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.1.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. [5/31/2011];Field administration of stroke therapy - magnesium (fast-mag) trial. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00059332.

- 15.Llanes JN, Kidwell CS, Starkman S, Leary MC, Eckstein M, Saver JL. The los angeles motor scale (lams): A new measure to characterize stroke severity in the field. Prehospital Emergency Care. 2004;8:46–50. doi: 10.1080/312703002806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schuberg S, Song S, Saver JL, Mack WJ, Cen SY, Sanossian N. Impact of emergency medical services stroke routing protocols on primary stroke center certification in california. Stroke. 2013;44:3584–3586. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.000940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDonald CM, Cen S, Ramirez L, Song S, Saver JL, Mack WJ, et al. Hospital and demographic characteristics associated with advanced primary stroke center designation. Stroke. 2014;45:3717–3719. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alberts MJ, Hademenos G, Latchaw RE, Jagoda A, Marler JR, Mayberg MR, et al. Recommendations for the establishment of primary stroke centers. JAMA. 2000;283:3102–3109. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.23.3102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gropen TI, Gagliano PJ, Blake CA, Sacco RL, Kwiatkowski T, Richmond NJ, et al. Quality improvement in acute stroke. Neurology. 2006;67:88–93. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000223622.13641.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wojner-Alexandrov AW, Alexandrov AV, Rodriguez D, Persse D, Grotta JC. Houston paramedic and emergency stroke treatment and outcomes study (hopsto). Stroke. 2005;36:1512–1518. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170700.45340.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]