Introduction

Buccal mucosa squamous cell carcinoma (BMSCC) is a rare but aggressive form of oral cavity cancer, associated with a high rate of locoregional recurrence and poor survival [1]. Patients with BMSCC have a worse stage-for-stage survival rate than the patients with other oral cavity sites [2]. It is not known to spread to distant organs. In these patients combined modality treatment incorporating surgery, adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy should be considered as the best practice [3].

We report a case of locally advanced BMSCC which metastasised to left adrenal on presentation, picked up by PET-CT and later confirmed by CT-guided FNAC. An exhaustive pubmed search suggests that this is the first case of carcinoma buccal mucosa metastasising to adrenals, though rarely other sites of distant metastases have been reported; including brain, pericardial cavity, liver, lung, thyroid, bone and bone marrow [4]. We recommend a thorough metastatic workup including PET-CT for patients who present with advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinomas.

Case Report

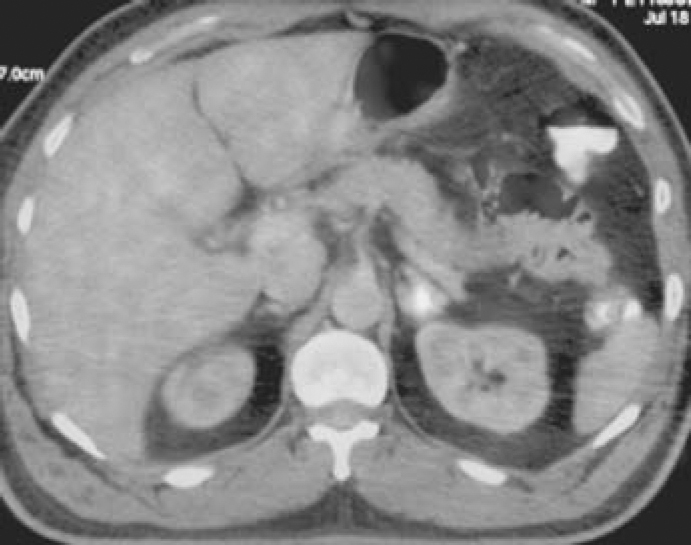

A 50 year old male presented with a 5 × 4 cm ulcero-proliferative growth in left buccal mucosa and a 6 × 5cm mass in left submandibular region of eight months duration. His CT face and neck revealed a 5.8 × 2.4 × 5.6 cm heterogeneously enhancing mass involving the left cheek and adjacent upper and lower lips, 5.8 × 3.8 × 3.7 cm necrotic lymph node in the left submandibular region with peripheral nodular enhancement and multiple left level II – IV lymph nodes, largest measuring 2.4 × 1.9 cm at level II. His whole body 3D PET-CT using 10 mci of FDG was suggestive of increased FDG concentration in mass involving the left cheek and adjacent upper and lower lips (SUV 3.4), 5.8 × 3.8 × 3.7 cm necrotic lymph node in the left submandibular region (SUV 2.5), multiple left level II – IV lymph nodes (SUV 1.8) and left adrenal gland (SUV 1.6) as shown in Fig. 1, Fig. 2. Histopathological examination of the growth in buccal mucosa revealed squamous cell carcinoma. CT-guided FNAC from left adrenal lesion (Fig. 3) was suggestive of squamous cell metastasis in left adrenal. In view of continuous severe pain in buccal growth and impending fungation of cervical nodal mass, the patient was started on palliative local radiotherapy followed by palliative chemotherapy which he tolerated poorly. He had rapid downhill course and was advised supportive and palliative care in view of poor performance status. He succumbed to advanced disseminated disease within three months of presentation.

Fig. 1.

Buccal carcinoma and the

Fig. 2.

Increased FDG uptake in left adrenal left submandibular nodal involve-gland, ment seen on PET-CT.

Fig. 3.

CT guided FNAC smears from left adrenal lesion showing clusters of malignant squamous cells (high power view of malignant cells in inset).

Discussion

Squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity ranks as the twelfth most common cancer in the world and the eighth most frequent in males. In USA, cancers of oral cavity comprises approximately 3% of all cancers, the most common subsite for oral cavity carcinomas being the tongue followed by floor of mouth [5]. However, BMSCC is the most common oral cancer in men and the third most common oral cancer in women in India; and accounts for up to one-third of all tobacco-related cancers [6]. This higher rate of BMSCC in India is likely related to the widespread practice of betel nut chewing, in addition to tobacco and alcohol. Other suspected but not confirmed etiologic agents include human papilloma virus, poor oral hygiene and chronic irritation [6, 7]. Patients usually present with a persistent ulcer or an exophytic growth in the gingivobuccal complex, loosening of teeth, ill-fitting dentures or trismus. Pain is a late feature. Patients with advanced disease present with orocutaneous fistula, severe trismus and lymph node metastasis. Many patients have associated premalignant lesions like leukoplakia and erythroplakia or premalignant condition like submucous fibrosis [6].

Depending on the specific site in the gingivobuccal complex (alveolus, gingivobuccal sulcus or buccal mucosa alone), the extent of the primary tumour and the status of lymph nodes, the treatment of these cancers may be by surgery or radiation therapy used alone or in combination, with or without chemotherapy [3, 6]. Treatment of BMSCC cancer is primarily surgical. The aim of surgical treatment is to excise the entire primary lesion with clear margins (1-2 cm) and also effectively treat the regional lymph nodes. This ablative surgery is followed by primary reconstruction to provide rapid healing, restore function and appearance and thereby improve patient's quality of life [6]. Post-operative chemoradiation offers improved loco-regional control versus post-operative radiation alone for high-risk histologic findings, including perineural invasion, close or positive surgical margins, extracapsular lymph node spread, multiple positive lymph nodes, and advanced T-stage. Post-op radiotherapy is usually given to 50-60 Gy and begins approximately 4-6 weeks after surgery [1, 3].

About 90% of recurrences occur within the first 1.5 years after treatment. Local recurrence is more common than regional recurrence, and has been reported between 23 to 32% [2, 8]. Locoregional control and survival rates may be greater with surgical excision plus post-operative radiation than with treatment with either modality alone [1]. Distant metastases are uncommon in buccal carcinoma. An exhaustive PubMed search suggests that this is the first case of carcinoma buccal mucosa metastasising to adrenals, though rarely other sites of distant metastases have been reported; including brain, pericardial cavity, lung, thyroid, bone and bone marrow [4, 5].

PET scan is not a standard workup for a carcinoma buccal mucosa in our institute. However, if there is a doubtful lesion on routine standard imaging which looks like a metastasis or if there is high index of suspicion of the patient harbouring metastatic disease, patient can be referred for PET-CT before taking him up for radical surgery or concurrent CCRT. PET-CT is increasingly becoming an important investigation in the primary and metastatic workup of head and neck carcinomas. FDG-PET/CT is superior to CT alone for assessing locoregional spread, treatment planning, detecting distant metastasis, picking up synchronous lesions, workup in carcinoma of unknown primary sites and for detecting recurrences in early and advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. PET/CT has a sensitivity of 89%, specificity of 95%, and accuracy of 92% in head and neck malignant conditions [4]. About 30-50% patients undergo a change in their treatment plan when assessed by PET-CT compared to CT scan alone [9]. The use of integrated PET/CT is more accurate than the use of PET alone for differentiating benign and metastatic adrenal gland lesions and allows early detection and accurate localization of adrenal lesions in oncology patients, thereby facilitating treatment planning. The sensitivity, specificity and accuracy of PET in depicting adrenal gland metastasis in oncology cases were 74, 73, and 74%, respectively, whereas those of integrated PET/CT were 80, 89, and 84%, respectively (p values; 0.5, 0.125, and 0.031, respectively) [10].

PET-CT was diagnostic for adrenal metastatic lesion in this patient, later confirmed by CT-guided FNAC. Although PET-CT is not a cost-effective investigation for standard workup of all oral carcinomas, we recommend that a PET-CT can be considered for patients who present with long-standing locally advanced untreated primary oral SCC with high risk of having metastatic disease, patients with unknown primary, patients with equivocal CT/MRI findings and for detecting persistent or recurrent disease and patients.

Conflicts of Interest

None identified.

References

- 1.Lin D, Bucci MK, Eisele DW, Wang SJ. Squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa: a retrospective analysis of 22 cases. Ear, Nose Throat J. 2008;87:582–586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diaz EM, Jr, Holsinger FC, Zuniga ER, Roberts DB, Sorensen DM. Squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa: one institution's experience with 119 previously untreated patients. Head Neck. 2003;25:267–273. doi: 10.1002/hed.10221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Badakh DK, Grover AH. The efficacy of postoperative radiation therapy in patients with carcinoma of the buccal mucosa and lower alveolus with positive surgical margins. Indian J Cancer. 2005;42:51–56. doi: 10.4103/0019-509x.15101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pichi B, Marchesi P, Manciocco V. Carcinoma of the buccal mucosa metastasizing to the talus. J Craniofac Surg. 2009;20:1142–1145. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181abb469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Manon RR, Myers JN, Khuntia D, Harari PM. Oral Cavity Cancer. In: Wazer DE, Freeman C, Prosnitz LR, editors. Perez and Brady's principles and practice of Radiation Oncology. 5th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. pp. 891–912. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Misra S, Chaturvedi A, Misra NC. Management of gingivobuccal complex cancer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90:546–553. doi: 10.1308/003588408X301136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chocolatewala NM, Chaturvedi P. Role of human papilloma virus in the oral carcinogenesis: an Indian perspective. J Cancer Res Ther. 2009;5:71–77. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.52788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoo MH, Cho GS, Lee YS, Roh JL, Choi SH, Nam SY. Squamous cell carcinoma of the buccal mucosa: Treatment results and recurrence features of 23 cases. Oral Oncology Supplement. 2009;3:169–170. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ha PK, Hdeib A, Goldenberg D. The role of positron emission tomography and computed tomography fusion in the management of early-stage and advanced-stage primary head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:12–16. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross MD, Avram A, Fig LM, Fanti S, Al-Nahhas A, Rubello D. PET in the diagnostic evaluation of adrenal tumors. Q J Nucl Med Mal Imaging. 2007;51:272–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]