Abstract

The present study examined the specificity in relations between observed withdrawn and intrusive parenting behaviors and children's internalizing and externalizing symptoms in an at risk sample of children (ages 9 to 15-years-old) of parents with a history of depression (N = 180). Given past findings that parental depression and parenting behaviors may differentially impact boys and girls, gender was examined as a moderator of the relations between these factors and child adjustment. Correlation and linear regression analyses showed that parental depressive symptoms were significantly related to withdrawn parenting for parents of boys and girls and to intrusive parenting for parents of boys only. When controlling for intrusive parenting, preliminary analyses demonstrated that parental depressive symptoms were significantly related to withdrawn parenting for parents of boys, and this association approached significance for parents of girls. Specificity analyses yielded that, when controlling for the other type of problem (i.e., internalizing or externalizing), withdrawn parenting specifically predicted externalizing problems but not internalizing problems in girls. No evidence of specificity was found for boys in this sample, suggesting that impaired parenting behaviors are diffusely related to both internalizing and externalizing symptoms for boys. Overall, results highlight the importance of accounting for child gender and suggest that targeting improvement in parenting behaviors and the reduction of depressive symptoms in interventions with parents with a history of depression may have potential to reduce internalizing and externalizing problems in this high-risk population.

Keywords: Depression, parenting, internalizing symptoms, externalizing symptoms, parenting specificity, child gender

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) is a prevalent and debilitating mental health problem that affects more than 20 million adults in the United States annually, approximately 7.5 million of whom are parents of children and adolescents. Importantly, children of depressed parents experience significant levels of both internalizing and externalizing problems compared to children of nondepressed parents (Gunlicks & Weissman, 2008; National Research Council/Institute of Medicine [NRC/IOM], 2009). Although multiple risk factors may explain this relation, parental depressive symptoms and parenting behaviors are two potentially important risk mechanisms that may serve as targets of change in interventions (Compas et al., 2015; Goodman et al., 2011; Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000). Further, child gender may moderate the association between maternal depression and child adjustment (Sheeber, Davis, & Hops, 2002).

Parental depression, including levels of current depressive symptoms, contributes to a chronically and unpredictably stressful environment for children in part because depressed parents vacillate between high levels of withdrawn (i.e., emotionally and physically unavailable) and intrusive (i.e., irritable, hostile, coercive) behaviors (e.g., Hammen, Brennan, & Shih, 2004; Jaser et al. 2005, 2008). Depressive symptoms have consistently been associated with increased parental hostility, inconsistent discipline, negative affect, and lower responsiveness to children (Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000). Past research has been guided by the hypothesis that parenting problems reflect the affective, cognitive, and behavioral characteristics of depression including sad mood, loss of interest, fatigue, and irritability (NRC/IOM, 2009). For example, parents experiencing sad mood and fatigue may be less able to attend to children’s needs, whereas parents experiencing heightened irritability as a result of depression may express more negative affect and display harsh or inconsistent discipline with their children as a result of decreased tolerance for normative child behavior (Lovejoy et al., 2000). Dix and Meunier (2009) examined 13 potential processes that could account for the association between parental depressive symptoms and parenting, citing research that depressed parents are more self-oriented, attend less to child-relevant information, display more negative/less positive affect, and more favorably evaluate coercive responses to children. Gender differences in children’s risk have been found whereby daughters of parents with a history of depression may be at greater risk for developing depression than sons, a finding that could be partly explained by increased sensitivity to the stress associated with parental depression in girls (e.g., Hankin, Mermelstein, & Roesch, 2007) or different socialization of sons versus daughters (Goodman et al., 2011).

Although it is well established that deficits in parenting are associated with depression, the field lacks consensus on the conceptualization and operationalization of parenting behavior categories. This may be due to differences in theoretical models and the measures used to assess parenting. Past studies have largely grouped parenting patterns into broad categories, such as negative parenting (e.g., Wilson & Durbin, 2010), while paying relatively less attention to possible subtypes of negative parenting. This approach may lead researchers to underestimate the strength of and sources of variability in the association between parenting and child adjustment by failing to account for the subtypes of parenting deficits. Furthermore, examining negative parenting broadly is not conducive to clinical application; studies must identify which specific types of negative parenting are associated with problematic youth outcomes, before specific recommendations about parenting and preventive interventions can be made.

Dix and Meunier (2009) described several parenting deficits that have been consistently associated with parents’ depressive symptoms, including withdrawal, intrusiveness, and flat and negative emotional expression to children. Whereas Dix and Meunier combined these deficits into a single construct of low parenting competence, Lovejoy et al. (2000) divided parenting deficits into three categories: negative (including negative maternal affect or hostile or coercive behavior), disengaged (including neutral affect and uninvolved with the child; e.g., ignoring, withdrawal, silence during gaze aversion), and positive (including pleasant, enthusiastic interactions between parent and child). Drawing on these two important reviews, the current study examines two subtypes of negative parenting in relation to child adjustment by examining intrusive parenting, which includes hostile, intrusive, and coercive parenting behaviors (i.e., parenting errors of commission) and withdrawn parenting, which refers to a lack of involvement and responsiveness to the child (i.e., parenting errors of omission).

Intrusive and withdrawn parenting have been associated with increased levels of internalizing problems (see McKee, Colletti, Rakow, Jones, & Forehand, 2008; McLeod, Weisz, & Wood, 2007, for reviews) and externalizing problems (see Capaldi, Chamberlin, & Patterson, 1997; McKee, Colletti et al., 2008; McMahon, Wells, & Kotler, 2006, for reviews). Notably, evidence suggests that withdrawn parenting may place children at risk for externalizing problems. By failing to engage in age-appropriate limit setting and supervision, parents may fail to curb or stop children’s disruptive and/or aggressive behavior (e.g., Kawabata, Alink, Tseng, IJzendoorn, & Crick, 2011). Additionally, intrusive parenting may place children particularly at risk for developing internalizing problems. Researchers have proposed that repeated hostile confrontations between children and parents result in increased psychological distress/anxiety, feelings of hopelessness, and worthlessness in offspring, all of which are symptoms of internalizing problems (e.g., Burge & Hammen, 1991; Ge, Best, Conger, & Simons, 1996). Prior work on child gender has noted stronger effects of parenting for girls compared to boys (e.g., Berg et al., 2007; Casas et al., 2006). Such findings may reflect girls’ tendency to be attuned to interpersonal relationship quality to a greater degree than boys, making them more vulnerable to the interpersonal features of parenting style (Cyranowski, Frank, Young, & Shear, 2000; Oldehinkel, Veenstra, Ormel, de Winter, & Verhulst, 2006; Sheeber et al., 2002).

To date no studies have examined whether intrusive and withdrawn parenting behaviors have specific associations with internalizing and externalizing problems for girls and boys within the same sample. Studying specificity in the relation of these dimensions is particularly important in the context of parental depression, as parents are more likely to display these parenting behaviors and children are at increased risk to develop both internalizing and externalizing problems. According to Caron, Weiss, Harris, and Catron (2006), such tests of the specific associations of types of parenting must take into account at least two parenting behaviors and two types of child problems, and examine whether one of the parenting behaviors is associated with one type of child problem after controlling for co-occurring parenting behaviors and the other type of child problem (i.e., testing for a unique association). The test of unique specificity establishes whether a variable (e.g., intrusive parenting) has a direct association with a given outcome (e.g., child externalizing symptoms), or whether that variable’s association becomes non-significant when indirect relations through other variables (e.g., withdrawn parenting and child internalizing symptoms) are controlled. Although several studies have tested parenting specificity with the aforementioned criteria (e.g., Caron et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2008), only one study to date by McKee, Forehand et al. (2008) has examined parenting specificity in the context of parental depression. McKee, Forehand et al. examined parenting dimensions derived from the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (Frick, 1991) that included parental warmth, monitoring, and inconsistent discipline; results indicated that parental warmth was uniquely related to externalizing problems. The current study builds on McKee, Forehand et al. study in three ways: first by examining intrusive and withdrawn parenting as categories of parenting behaviors exhibited by depressed parents (see Dix & Meunier, 2009; Lovejoy et al., 2000), second by utilizing direct observations of parenting behaviors rather than child report of parenting, and third by incorporating child gender as a moderator.

The current study provides the first examination of unique specificity for the relation of intrusive and withdrawn parenting with boys’ and girls’ internalizing and externalizing problems in the context of a history of parental depression. As noted above, prior research has found that (a) parental depressive symptoms and withdrawn and intrusive parenting are associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in youth, and (b) depression is associated with impairments in parenting. Thus, in preliminary analyses we examine whether these associations are replicated in bivariate correlations and multiple linear regression analyses in the current sample. In the primary focus of this study, with regard to specificity, we hypothesize that withdrawn parenting will be uniquely associated with externalizing problems while intrusive parenting will be uniquely associated with internalizing problems. Given previous research on gender differences, we anticipate that the specific associations between parenting and child adjustment will be stronger for girls than for boys.

Methods

Participants

The sample included 180 families with 242 children (121 girls, 121 boys) between the ages of 9 and 15 years (M = 11.53, SD = 2.02) and the target parents (160 mothers, 20 fathers). All parents met criteria for at least one episode of MDD during the lifetime of their children (Median = 4.0 episodes; Current MDD, n = 48, Past MDD, n = 132). In consideration of the possible violation of independence of children within the same family, one child was randomly selected from each family with multiple children for all analyses. The final sample included 180 children (89 girls and 91 boys) between the ages of 9 and 15 years old (M = 11.46, SD = 2.00) and their parents (M = 41.96, SD = 7.53). This age range is suitable for investigating relations between parenting and child adjustment given that child adjustment problems increase in early to mid-adolescence (e.g., Hankin et al., 1998). Children were 74.4% Euro-American, 12.8% African-American, 3.3% Asian, 1.7% Latino or Hispanic, and 7.8% other or mixed ethnicity. Parents’ race/ethnicity included 82.2% Euro-American, 11.7% African-American, 1.1% Asian, 2.2% Latino or Hispanic, and 2.8% other or mixed ethnicity. Parents’ level of education included 5.6% of parents with less than high school, 8.9% completed high school, 30.6% had some college or technical school, 31.7% had a college degree, and 23.3% had a graduate education. The marital statuses of the parents were 61.7% married or co-habitating, 21.7% divorced, 10.5% never married, 5.0% separated, and 1.1% widowed. Annual household income ranged from less than $5,000 to more than $180,000 (median = $40,000).

Measures

Parental depression diagnoses

Parents’ current and past history of MDD was assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID; First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2001), a semi-structured diagnostic interview that was administered to the target parent by a trained research assistant or graduate student. The SCID is frequently used and has been shown to yield reliable diagnoses of past and current Major Depressive Disorder in adults (First et al., 2001). Inter-rater reliability was calculated on approximately 25% of randomly selected interviews and indicated 93% agreement (κ= 0.71) for diagnoses of MDD.

Parent depressive symptoms

Parents’ current depressive symptoms were assessed with the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II), a standardized and widely used self-report checklist of depressive symptoms with adequate internal consistency and validity in distinguishing severity of MDD (Beck, Steer, Ball, & Ranieri, 1996; Steer, Brown, Beck, & Sanderson, 2001). Internal consistency in the current sample was α = .93.

Observed parenting behaviors

A global coding system, the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (IFIRS; Melby et al., 1998), was used to code two videotaped 15-min conversations between the target parent and child. In the first task, the parent and child were instructed to discuss a recent pleasant family activity using a list of prompted questions that were written to elicit positive affect from the dyad (e.g., What are some other fun activities that we would like to do together?). In the second task, the parent and child discussed a recent family stressful event using a list of prompted questions that were written to elicit negative affect from the dyad (e.g., When mom/dad is sad, down, irritable or grouchy what usually happens?). The IFIRS system is designed to measure behavioral and emotional characteristics of the participants at both the individual (i.e., examination of the general mood or state of being of a person) and dyadic (i.e., examination of behavior directed by one person toward another person in an interaction context) level. Each behavioral code is rated on a 9-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all characteristic of the participant during the interaction) to 9 (the behavior is mainly characteristic of the participant during the interaction). In determining the score for each code, the frequency and the intensity of behavior, as well as the contextual and affective nature of the behavior, are considered. Pairs of trained research assistants independently coded the two parent-child interaction tasks and coders met to establish consensus on any discrepant codes (i.e., codes rated greater than 2 points apart). The mean rate of agreement for codes assessing parents’ behavior was 73%. Weekly training meetings were also held in order to prevent coder drift.

Observations of parent-child interactions by independent raters can provide relatively objective data about parenting (McKee, Jones, Forehand, & Cueller, 2013). Thus, this macro-level system is ideal for assessing patterns of behavior that comprise the ongoing, dynamic process of interaction (Melby & Conger, 2001). The validity of the IFIRS system has been established with correlational and confirmatory factor analyses (Alderfer et al., 2008; Melby & Conger, 2001).

Although parents and children were scored on a wide range of emotional and behavioral dimensions, the current study focused on seven specific codes that were selected to assess two subtypes of negative parenting—withdrawn and intrusive parenting—based on theory-driven and empirically supported distributions in parenting due to depression (see Table 1). Following procedures used previously with the IFIRS codes (e.g., Compas et al., 2010; Lim, Wood, & Miller, 2008), scores were aggregated across the two tasks and combined to create a composite code for each parenting category. Codes from the Dyadic Interaction Scales were chosen to capture withdrawn or intrusive behaviors of the parents that were directed at the child. Inter-rater reliability was calculated for each IFIRS code using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC); ICCs ranged from .52 to .94. The withdrawn parenting composite included codes of neglect-distancing (Mean ICC = .52), child-monitoring (Mean ICC = .58; reverse coded), quality time (Mean ICC = .94; reverse coded), and listener responsiveness (Mean ICC = .78; reverse coded), α = .76. The intrusive parenting composite included hostility (Mean ICC = .78), intrusiveness (Mean ICC = .72), and guilty coercion (Mean ICC = .76), α = .72. The significant positive association between withdrawn and intrusive parenting composites (r = .52, p < .01) suggests that these two categories represent related but distinct aspects of parenting.

Table 1.

Composite IFIRS Codes for Withdrawn and Intrusive Parenting

| Parenting Behavior(s) Associated

with Depressive Symptoms |

IFIRS Code | IFIRS Code Definition | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Withdrawn Parenting |

Self-focused attention; low motivation for social interaction with children |

Neglect/ Distancing (ND) |

The degree to which the parent is uncaring,

apathetic, uninvolved, ignoring, aloof, unresponsive, self-focused, and/or adult-oriented; the parent displays behavior that minimizes the amount of time, contact, or effort he/she has to expend on the child. |

| Low responsiveness and high

disengagement; lack of emotional support or reciprocity; tendency to select responses that require low effort |

Listener Responsiveness (LR) [Reverse coded] |

The degree to which the focal attends to,

shows interest in, acknowledges, and validates the verbalizations of the other person (the speaker) through the use of nonverbal backchannels and verbal assents. A responsive listener is oriented to the speaker and makes the speaker feel like he/she is being listened to rather than feeling like he/she is talking to a blank wall. |

|

| Lack of interest in and knowledge of

the activities of the child |

Child Monitoring (CM) [Reverse coded] |

Assesses the parent’s knowledge and

information as well as the extent to which the parent pursues information concerning the child’s daily life and daily activities. It measures the degree to which the parent knows what the child is doing, where the child is, and with whom. |

|

| Less social involvement; lack of

involvement between parent and child |

Quality Time (QT) [Reverse coded] |

Assesses the extent or quality of the

parent’s involvement in the child’s life outside of the immediate setting; represents time “well-spent” versus superficial involvement |

|

|

Intrusive Parenting |

Negative emotionality; disturbed

contingent responses to child behaviors; tendency to react to challenging child behaviors with anger |

Hostility (HS) | Measures the degree to which the focal

displays hostile, angry, critical, disapproving, and/or rejecting behavior toward the other interactor’s behavior (actions), appearance, or state. |

| Use of harsh control associated with

thoughts of parental incompetence |

Intrusive (NT) | Assesses intrusive and over-controlling

behaviors (e.g., over-monitoring, interfering with child’s autonomy) that are parent-centered rather than child centered. Does not reflect positivity or warmth. Task completion or the parent’s own needs appear to be more important than promoting the child’s autonomy. |

|

| Increased manipulative parenting

(e.g., guilt induction, shaming, conditional loving) |

Guilty Coercive (GC) |

The degree to which the focal achieves goals

or attempts to control or change the behavior or opinions of the other by means of contingent complaints, crying, whining, manipulation, or revealing needs or wants in a whiny or whiny-blaming manner. These expressions convey the sense that the focal’s life is made worse by something the other interactor does. |

Emotional and behavioral problems

Parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001) to assess total internalizing and externalizing problems in children and adolescents. These scales were selected to represent the range of problems that have been identified in children of depressed parents (e.g., Beardslee, Wright, Gladstone, & Forbes, 2007; Clarke et al., 2001). The CBCL includes a 118-item checklist of problem behaviors that parents rate as 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), or 2 (very true or often true) of their child in the past six months. Adolescents completed the Youth Self-Report (YSR; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), the self-report version of the CBCL for adolescents aged 11 to 18 years old. Reliability and validity of the CBCL and YSR are well established (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001). Internal consistency (α) in the current sample ranged from .79 to .91 for the scales used in this study. Children 9 and 10 years of age also completed this self-report to allow for complete data on all measures. The internal consistency for the YSR scales was adequate with this younger age group in the current sample (all α ≥ .80).

To reduce the number of analyses and control for method variance, composite variables were created from parent and child reports of internalizing and externalizing symptoms by converting parent and child reports to standardized z-scores and calculating the mean of the z-scores for each variable. The CBCL and YSR internalizing (r = .42, p < .001) and externalizing (r = .47, p < .001) z-scores in our sample were significantly positively correlated at a level comparable to those reported in the standardization of the measure (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Procedure

Participants were part of a larger study testing the efficacy of a family group cognitive-behavioral intervention to prevent depression and other mental health problems in children of parents with a history of MDD. Families were recruited through a variety of sources in and around a southern metropolitan area and a small northeastern city, including mental health clinics and local media outlets. Families were eligible if the parent met criteria for MDD either currently or during the lifetime of her or his child (or children) and the following criteria were met: (a) parent had no history of Bipolar I disorder, schizophrenia, or schizoaffective disorder; (b) children had no history of autism spectrum disorders, mental retardation, Bipolar I disorder, or schizophrenia; and (c) children did not currently meet criteria for conduct disorder or substance/alcohol abuse or dependence. Children with conduct disorder were excluded because of evidence that group interventions with children with disruptive behavior disorders can lead to contagion of these problems among group members (Dishion & Dodge, 2005). Therefore, the current sample is representative of families of depressed parents where children are at-risk for the development of internalizing and externalizing problems.

Families who met the eligibility criteria were invited into the laboratory to participate in a baseline assessment where they completed a battery of questionnaires, more extensive semi-structured interviews to confirm their eligibility, and two 15-minute parent-child videotaped interaction tasks. All data used in the present study were collected at the baseline assessment prior to randomization and participation in the intervention. The Institutional Review Boards at the two universities approved all procedures. Clinical graduate students completed all semi-structured interviews and conducted the parent-child interaction tasks. All participants were compensated $40 for the baseline assessment.

Data Analyses

All analyses were conducted using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) using AMOS (IBM SPSS AMOS, version 22: Arbuckle, 2013) in order to include the 8.89% of participants with partial data. Means and standard deviations for observed parenting behaviors, composite scores of children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and parents’ depressive symptoms were calculated, and skewness for all variables was assessed. Potential differences by child gender or parental depression status, as assessed by the SCID, were examined for all variables in a series of t-tests.

Bivariate Pearson’s correlations were calculated as a preliminary analysis to examine associations among observed withdrawn and intrusive parenting behaviors, parents’ depression status, and children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Child’s age was included in the correlation matrix to examine possible associations with parenting and child adjustment. Further preliminary analyses included multiple linear regressions to investigate the association between parental depressive symptoms and parenting behaviors. In the first regression analysis predicting withdrawn parenting, the BDI-II was entered along with intrusive parenting to control for co-occurring intrusive parenting behaviors. Similarly, withdrawn parenting was controlled in the regression analysis of parental depressive symptoms (BDI-II) predicting intrusive parenting.

To examine the question of interest (i.e., the extent to which parenting behaviors and parental depressive symptoms uniquely predict internalizing and externalizing behaviors in boys and girls), we conducted a series of multiple linear regressions. In one set, children’s internalizing problems served as the outcome variable. In the other, children’s externalizing problems was the dependent variable. In both regressions, we entered predictors in two steps. In step 1, we entered parent BDI-II both withdrawn and intrusive parenting. This step enabled us to examine the relation of each type of parenting to children’s internalizing and externalizing problems while controlling for parental depressive symptoms. Individual beta weights represent the contributions of each parenting type. In step 2, we entered the alternative type of child outcome. When internalizing problems was the dependent variable, the step 2 predictor was externalizing problems; conversely, when externalizing problems was the dependent variable, the step 2 predictor was internalizing problems. This enabled us to re-examine beta weights for intrusive and withdrawn parenting after controlling for the other outcome, thus testing the specificity hypothesis.

Because these relations could differ by child gender, we simultaneously tested this model for boys versus girls, using the multi-group option in AMOS. In the initial test of these models, we placed no cross-gender constraints on the parameter estimates. In subsequent tests, we constrained specific regression weights to be equal across groups, thereby testing for gender differences in each beta weight individually (i.e., a 1 degree-of-freedom change in chi-square). Finally, we tested interaction effects for gender to determine whether evidence emerged for a diathesis-stress model (i.e., sources of vulnerability amplify risk for maladaptation given poor experiences; Monroe & Simons, 1991; Zuckerman, 1999) or differential susceptibility model (i.e., sources of vulnerability not only amplify risk for maladaptation given poor experiences, but also increase the probability of positive adaption given high-quality caregiving experiences; Belsky & Pluess, 2009).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive Statistics

All variables were normally distributed with skewness < 1. Table 2 provides descriptive statistics for observed parenting behaviors, children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and parents’ BDI-II. T-scores on the YSR/CBCL scale composites at baseline are provided as a normative reference point for this sample (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001), though z-scores are used for analyses. The percent of children in the clinical range (T > 70, 98th percentile) was 7.5% on the YSR internalizing scale, 0.6% on the YSR externalizing scale, 10.3% on the CBCL internalizing scale, and 5.7% on the CBCL externalizing scale (2% would be expected to exceed this cutoff, based on normative scale data). These scores are similar to those reported for children of depressed parents in other studies, including the STAR*D trial (Foster et al., 2008). As expected, these data indicate that this is an at-risk sample as reflected by moderately elevated mean T-scores and the portion of the sample in the clinical range (2 to 4 times greater than would be expected based on the norms for most scales). Parents in and out of episode, as determined by the SCID, were compared on current depressive symptoms, parenting, and children’s problem scales. These groups were significantly different only on current depressive symptoms such that parents in episode were found to endorse significantly more symptoms on the BDI-II (M = 27.9; SD = 10.9) compared to parents not in episode (M = 16.1, SD = 11.7), t (180) = 6.10, p < .001. No variables of interest significantly differed as a function of child gender (ps > .10).

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations and Descriptive Statistics

| Measures | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Parent BDI-II Score | --- | .29** | .21† | .22* | .24* | .05 |

| 2. Withdrawn Parenting | .25* | --- | 46*** | .11 | .06 | .15 |

| 3. Intrusive Parenting | .14 | .56*** | --- | .26* | .22* | .22* |

| 4. Child Internalizing Problems | .37*** | .27* | .31** | --- | .67*** | .07 |

| 5. Child Externalizing Problems | .30** | .53*** | .46*** | .67*** | --- | .05 |

| 6. Child Age | .15 | .14 | -.03 | .02 | .11 | --- |

| Boys | ||||||

| M | 19.47 | 36.09 | 18.75 | 57.54 | 51.74 | 11.26 |

| SD | 13.73 | 6.22 | 7.02 | 8.61 | 8.21 | 2.07 |

| Girls | ||||||

| M | 18.98 | 37.01 | 19.67 | 56.25 | 52.40 | 11.66 |

| SD | 11.35 | 6.74 | 8.18 | 9.98 | 9.68 | 1.92 |

Note. Boys are above the diagonal, girls are below the diagonal. BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory—II. Means and standard deviations for children’s internalizing and externalizing symptoms are reported as T-scores to provide a normative reference point (all analyses used z-scores of the composite CBCL/YSR scores for each type of symptom).

p = .052,

p < .05,

p ≤ .01,

p < .001

Bivariate correlation analyses

Bivariate correlations for parenting behaviors, parents’ current depressive symptoms, and children’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors are presented separately for boys and girls in Table 2. Consistent with findings from prior research, parents’ current depressive symptoms, as measured by the BDI-II, were significantly positively correlated with children’s internalizing symptoms and externalizing symptoms in boys and girls. Parental depressive symptoms were also significantly related to higher levels of observed withdrawn parenting behaviors for parents of boys and girls; however, the association between parental depressive symptoms and intrusive parenting approached significance for parents of boys (p = .052), but not for parents of girls. Intrusive parenting was significantly positively correlated with both internalizing and externalizing problems in boys and girls. Withdrawn parenting was significantly positively correlated with internalizing and externalizing problems for girls, but was not significantly associated with either measure of adjustment for boys. Finally, child age was significantly associated only with intrusive parenting for boys in this sample.

Linear Regression Analyses

Linear regression analyses were conducted to analyze the association between current parental depressive symptoms and each type of parenting behavior when controlling for the other type of parenting behavior. When controlling for withdrawn parenting in the first regression analysis, the BDI-II was not significantly associated with intrusive parenting for parents of boys or girls (p > .10). However, the BDI-II was significantly related to withdrawn parenting for parents of boys when controlling for intrusive parenting (β = .20, p < .05) and the relation between the BDI-II and withdrawn parenting approached significance for parents of girls when controlling for intrusive parenting (β = .17, p = .06).

Specificity in Parenting and Child Adjustment

Linear regression analyses were conducted to test the primary hypothesis of the study: the association between each type of parenting behavior and internalizing and externalizing behaviors. Table 3 shows the results of these analyses when internalizing problems served as the dependent variable. Initially, intrusive, but not withdrawn, parenting significantly predicted internalizing problems for boys, and this association approached significance for girls in this sample (step 1). When controlling for externalizing problems (step 2), parental depressive symptoms was a unique predictor of internalizing problems for girls; however, neither type of parenting nor the BDI-II uniquely predicted internalizing problems in boys.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting Child Internalizing Problems (Males: N = 91; Females: N = 89)

| Predictor | Males | Females | Sex diff:

Δχ2(1) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | ||

| Step 1 | .05 | .07 | |||||||

| Parent BDI-II | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.18 | 0.05*** | 0.02 | 0.33 | 2.95† | ||

| Withdrawn parenting | −0.01 | 0.03 | −0.06 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.50 | ||

| Intrusive parenting | 0.05* | 0.02 | 0.25 | 0.05† | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.00 | ||

| Step 2 | .36*** | .29*** | |||||||

| Parent BDI-II | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03* | 0.01 | 0.21 | 3.27† | ||

| Withdrawn parenting | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | −0.05 | 0.03 | −0.18 | 2.19 | ||

| Intrusive parenting | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.04 | ||

| Child externalizing

problems |

0.61*** | 0.08 | 0.64 | 0.67*** | 0.10 | 0.67 | 0.22 | ||

Note.

p < .06,

p < .05,

p ≤ .001

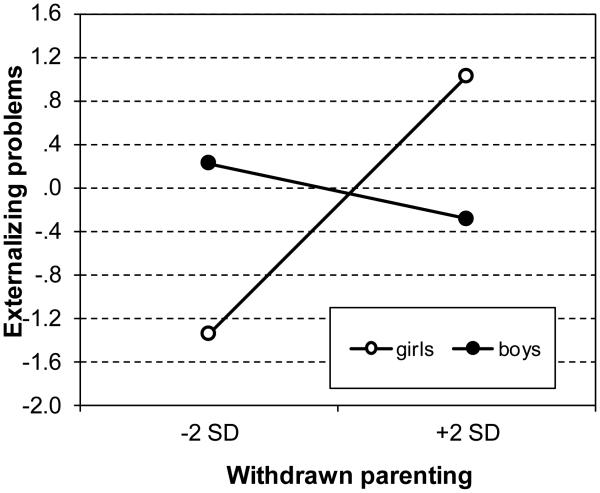

Table 4 shows the results when children’s externalizing problems served as the dependent variable. In step 1 of the regression, parental depressive symptoms and intrusive parenting (approaching significance; p = .056) predicted externalizing problems in boys, whereas depressive symptoms (approaching significance; p = .052) and both types of parenting significantly predicted externalizing problems in girls. When internalizing problems were added to the model in step 2, neither parental depressive symptoms nor parenting were significantly related to externalizing problems for boys. However, the relation between withdrawn, but not intrusive, parenting remained significant for girls in step 2. The association between withdrawn parenting and externalizing problems was significantly stronger for girls than for boys (χ² = 10.29, p < .001). To portray this interaction across 95% of the proposed predictor we conducted simple slope plots and calculations at −2 SD and +2 SD from the centered mean of withdrawn parenting (see Figure 1). Following recommendations set by Roisman et al. (2012) for examining differential susceptibility (e.g., the theory that many sources of vulnerability may amplify risk for maladaptation given poor caregiving experiences but increase the probability of positive adaptation given high-quality caregiving experiences; Belsky & Pluess, 2009), the proportion of the interaction (PoI) index was calculated to better understand the ratio of externalizing problems in girls under different levels of withdrawn parenting. PoI indices approximating .50 and exceeding .16 are regarded as yielding support for differential susceptibility, whereas values between .00 and .16 provide stronger support for diathesis stress (see Roisman et al., 2012). The PoI index was .55 ,suggesting differential susceptibility.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Regression Analysis for Variables Predicting Child Externalizing Problems (Males: N = 91; Females: N = 89)

| Predictor | Males | Females | Sex diff:

Δχ2(1) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | B | SE B | β | ΔR2 | ||

| Step 1 | 0.04 | 0.26*** | |||||||

| Parent BDI-II | 0.02* | 0.01 | 0.22 | 0.03† | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.09 | ||

| Withdrawn parenting | −0.03 | 0.03 | −0.10 | 0.10*** | 0.03 | 0.36 | 8.79** | ||

| Intrusive parenting | 0.05† | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.05* | 0.03 | 0.23 | 0.02 | ||

| Step 2 | 0.37*** | 0.24*** | |||||||

| Parent BDI-II | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.53 | ||

| Withdrawn parenting | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.06 | 0.09*** | 0.03 | 0.33 | 10.29*** | ||

| Intrusive parenting | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.11 | 0.15 | ||

| Child internalizing

problems |

0.66*** | 0.09 | 0.64 | 0.56*** | 0.08 | 0.55 | 0.82 | ||

Note.

p < .06,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p ≤ .001

Figure 1.

Plot of Gender x Withdrawn parenting interaction on Externalizing problem

Discussion

The findings from the present multi-method, multi-informant study extend previous research by examining two distinct types of negative parenting, intrusive and withdrawn behaviors, in relation to internalizing and externalizing problems in children of depressed parents. Previous research has consistently demonstrated that intrusive and withdrawn parenting patterns, which parents with current or past depression are likely to display, are risk factors for the development of internalizing and externalizing problems in offspring (Goodman et al., 2011). However, past findings on parental depression have not included specificity analyses regarding the association between withdrawn parenting, intrusive parenting, and child adjustment (see McKee, Colletti, et al., 2008, for a review).

In line with current research on parental depression, parents’ current depressive symptoms were positively correlated with observed withdrawn and intrusive parenting behaviors and child internalizing and externalizing symptoms for boys, and withdrawn parenting and internalizing and externalizing problems for girls (Dix & Meunier, 2009; Goodman et al., 2011). Parental depressive symptoms were not associated with increased levels of observed intrusive parenting for girls, suggesting that parents may respond differently to their sons and daughters even when experiencing depressive symptoms. Regarding developmental effects, child age was only significantly associated with intrusive parenting in parents of boys, suggesting that parents may display increased hostile or intrusive behaviors for older sons. Future studies utilizing a comparison group of healthy controls (i.e., parents without a history of depression) would aid in determining whether this effect is unique to children of parents with a history of depression.

When controlling for intrusive parenting in preliminary regression analyses, parental depressive symptoms were significantly associated with withdrawn parenting for boys and the relation approached significance for girls. However, parental depressive symptoms were not significantly associated with intrusive parenting when controlling for withdrawal, suggesting that depressive symptoms may be more strongly related to withdrawn than intrusive parenting, or that the association of the current depressive symptoms and intrusiveness may be best explained through co-occurring withdrawn parenting behaviors. Interestingly, levels of observed parenting and child problems did not differ based on parents’ current MDD diagnostic status based on the SCID, a finding that supports recent conceptualizations that depression may best be understood as a dimensional rather than categorical disorder (e.g., Hankin, Fraley, Lahey, & Waldman, 2005; Hyman, 2010).

Regarding the relation between withdrawn parenting and child adjustment, bivariate correlation analyses demonstrated a significant relationship between this type of parenting and internalizing and externalizing symptoms in girls but not boys. This suggests that withdrawn parenting may be related to both types of problems for girls and echoes past findings that parenting may be more influential for daughters compared to sons. In the regression analysis, withdrawn parenting was not significantly related to internalizing problems in boys or girls when controlling for parental depressive symptoms and intrusive parenting. Rather, only parents’ current depressive symptoms was significant for girls, but not boys, suggesting that the original association between parental withdrawal and girls’ internalizing problems may be better explained through a direct influence of parental depressive symptoms. In contrast, withdrawn parenting remained a significant predictor of externalizing problems in girls when accounting for internalizing problems, intrusive parenting, and parental depressive symptoms in the regression analysis, demonstrating a unique relation for withdrawn parenting and daughters’ externalizing problems. Broadly, these findings support research that depressed parents who exhibit withdrawn parenting behaviors may contribute to externalizing symptoms by failing to engage in age-appropriate limit setting and supervision to curb or stop children’s disruptive and/or aggressive behavior (e.g., Kawabata et al., 2011). Regarding gender differences, analyses examining the interaction between parental withdrawal and externalizing problems in girls suggested differential susceptibility, such that low levels of withdrawn parenting are related to low externalizing problems compared to boys, while high levels of withdrawn parenting are related to high externalizing problems compared to boys. Multiple processes may account for the greater influence of withdrawn parenting on girls’ adjustment compared to boys. For example, studies have suggested that boys and girls cope differently with the stress associated with parental depression, even within the same sibling group (e.g., Klimes-Dougan & Bolger, 1998), which may differentially influence psychosocial adjustment. Etiological models attempting to explain such differences have also focused on hormonal (Angold et al., 1999), genetic (e.g., Silberg, Rutter, & Eaves, 2001), culturally shaped values and vulnerabilities (Seligman et al., 1995), and stress exposure and stress processes (Shih et al., 2006; England & Sim, 2009).

In line with previous research, intrusive parenting was significantly and positively correlated with children’s externalizing and internalizing symptoms for all adolescents in the sample. In testing for a unique association, however, intrusive parenting was not related to child internalizing or externalizing problems when accounting for the other type of child problem. This suggests that the relation between parenting and internalizing symptoms may be best explained by intrusive parenting and externalizing symptoms; conversely the relation between intrusive parenting and externalizing symptoms may be best explained by intrusive parenting and internalizing symptoms. Thus, although intrusive parenting is significantly related to increased levels of children’s internalizing and externalizing problems in this sample, there is no evidence for specificity of this parenting construct.

Taken together, findings from this sample of parents with a history of depression and their children demonstrate that withdrawn parenting behaviors are specifically linked to externalizing problems in girls, while intrusive parenting may be more diffusely related to both internalizing and externalizing symptoms in both boys and girls. Neither intrusive parenting nor withdrawn parenting, when considered simultaneously and in the context of externalizing symptoms, was a unique predictor of internalizing symptoms in youth. One explanation for this finding arises from high rates of comorbidity for internalizing and externalizing disorders in youth (Pesenti-Gritti et al., 2008). Parenting behaviors may not have been uniquely associated with internalizing symptoms because of their strong associations with co-occurring externalizing symptoms. Alternatively, a mechanism aside from parenting, such as genetic transmission or the modeling of negative cognitive style, may account for internalizing problems in this sample. Instead, the regression analysis including all of the predictors for internalizing problems demonstrated that parenting and parental depressive symptoms were nonsignificant for boys, and yielded a significant relation only between parents’ current depressive symptoms and internalizing problems for girls. This finding is supported by previous research that girls may be more strongly influenced by parental depressive symptoms than boys (Sheeber et al., 2002).

The present study has several limitations that should be noted. First, children who had a diagnosis of Conduct Disorder or current MDD were excluded from participating in the study. Consequently, the sample does not entirely represent children of depressed parents, and the incidence of children’s maladjustment may be underestimated, as symptoms of these disorders are included in externalizing and internalizing symptoms, respectively. However, as evidenced by the elevated scores on the CBCL and YSR, this sample represents children at high risk for internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Second, because this study was cross-sectional, directionality could not be established. Although we tested unidirectional associations between parenting and internalizing and externalizing problems in children of depressed parents, current research has stressed the importance of examining child effects on parental behavior (Beach, Brody, Kogan, & Philibert, 2009). Characteristics of children (e.g., physical appearance, gender, behavior, temperament) likely function to influence parents’ perceptions, expectations, and/or beliefs about the child, which in turn impact child-directed behavior (Luster & Okagaki, 2006). Influences of child characteristics on parenting were not analyzed in this study, but could provide a more accurate picture of the relationship between parenting and child adjustment. Further, longitudinal investigations could better determine the temporal sequence among parental depressive episodes, parenting impairments, and child problems. Finally, because cross-sectional data (a) does not allow time to elapse between the putative cause and effect and (b) does not allow for statistical control for the prior levels of the dependent variable (see Cole & Maxwell, 2003), we did not test a meditational hypothesis in the present study. Future longitudinal studies should be conducted to better understand the relations between depressive symptoms, parenting behaviors, and child problems simultaneously in a path-analytic model.

Despite the aforementioned shortcomings, the current study also had several strengths. First, the examination of specificity for intrusive and withdrawn parenting and child adjustment has not previously been analyzed in the context of parental depression. Second, by utilizing observational measures of parenting behaviors, parent- and child-reports of internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and diagnostic interviews and self-report methods for depressive symptoms, results of the present study contain relatively little overlap in shared method variance. However, we acknowledge that two of the measures, parental BDI-II scores and CBCL ratings, may be confounded, and the BDI-II and child adjustment associations may be affected by shared method variance (e.g., Rowe & Kandel, 1997). Third, considering past findings of differential effects for parental depression and parenting for boys versus girls, examining these associations by gender is a significant strength. Finally, the sample size was relatively large, especially taking into account the use of observational measures, and allowed for greater statistical power.

In sum, this study replicated past findings in that parental depressive symptoms were significantly related to child internalizing and externalizing problems, and provided new data suggesting that parental depressive symptoms may be associated with withdrawn parenting for parents of boys and girls, and intrusive parenting for parents of boys only. Further, the association between depressive symptoms and withdrawn parenting when controlling for co-occurring intrusive parenting behaviors was found to be significant for boys and girls. Findings from this study extended previous work by examining the unique specificity of parenting behaviors and child adjustment by gender in the context of parental depression. Consistent with previous findings, intrusive parenting was correlated with elevated levels of internalizing and externalizing problems in boys and girls, but no patterns of specificity emerged from this subtype of negative parenting when controlling for the other type of symptom. A pattern of specificity emerged for withdrawn parenting such that greater levels of observed parental withdrawal predicted heightened externalizing problems for girls, but not for boys. As previously stated, longitudinal studies should further test the possibility that parents’ depressive symptoms directly influence internalizing problems in girls, even when accounting for parenting behaviors, while withdrawn parenting is the primary risk factor for externalizing problems for girls in this population. Additionally, further work should be conducted to better understand what specific risk factors underlie the relationship between parental depression and maladjustment for boys in this population. Findings from this and future studies can lead to the enhancement of parenting interventions focused on decreasing internalizing and externalizing problems in children of depressed parents (e.g., Compas et al., 2010) with sensitivity to child gender. Results from the present study suggest that targeting decreases in parental depressive symptoms and parental withdrawal may directly lead to decreases in girls’ internalizing and externalizing symptoms, respectively, in the context of parental depression.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants R01MH069940 and R01MH069928.

Contributor Information

Laura McKee, University of Georgia.

Rex Forehand, University of Vermont.

References

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families; Burlington, VT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer MA, Fiese BH, Gold JI, Cutuli JJ, Holmbeck GN, Goldbeck L, Patterson J. Evidence-based assessment in pediatric psychology: Family measures. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008;33:1046–61. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm083. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Worthman CM. Pubertal changes in hormone levels and depression in girls. Psychological Medicine. 1999;29:1043–1053. doi: 10.1017/s0033291799008946. doi:10.1017/s0033291799008946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL. IBM SPSS Amos 22 user’s guide. Amos Development Corporation; Crawfordville, FL: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Beach S, Brody G, Kogan S, Philibert R. Change in caregiver depression in response to parent training: Genetic moderation of intervention effects. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:112–117. doi: 10.1037/a0013562. doi:10.1037/a0013562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardslee W, Wright E, Gladstone T, Forbes P. Long-term effects from a randomized trial of two public health preventive interventions for parental depression. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:703–713. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.703. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, Ranieri WF. Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories – IA and –II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1996;67:588–597. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6703_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J, Pluess M. Beyond diathesis stress: Differential susceptibility to environmental influences. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(6):885–908. doi: 10.1037/a0017376. doi:10.1037/a0017376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA, Wiebe DJ, Beveridge RM, Palmer DL, Korbel CD, Upchurch R, Donaldson DL. Mother–child appraised involvement in coping with diabetes stressors and emotional adjustment. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32(8):995–1005. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm043. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burge D, Hammen C. Maternal communication: Predictions of outcome at follow-up in a sample of children at high and low risk for depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:174–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.2.174. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.100.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D, Chamberlain P, Patterson GR. Ineffective discipline and conduct problems in males: Associations, late adolescent outcome, and prevention. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 1997;2:343–353. doi:10.1016/s1359-1789(97)00020-7. [Google Scholar]

- Caron A, Weiss B, Harris V, Catron T. Parenting behavior dimensions and child psychopathology: Specificity, task dependency, and interactive relations. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:34–45. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_4. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casas JF, Weigel SM, Crick NR, Ostrov JM, Woods KE, Yeh EAJ, et al. Early parenting and children’s relational and physical aggression in the preschool and home contexts. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology. 2006;27:209–227. doi:10.1016/j.appdev.2006.02.003. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke GN, Hornbrook M, Lynch F, Polen M, Gale J, Beardslee W, Seeley J. A randomized trial of a group cognitive intervention for preventing depression in adolescent offspring of depressed parents. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:1127–1134. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1127. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.12.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Maxwell SE. Testing mediational models with longitudinal data: questions and tips in the use of structural equation modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:558. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.558. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.112.4.558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Champion JE, Forehand R, Cole DA, Reeslund KL, Fear J, Roberts L. Coping and parenting: Mediators of 12-month outcomes of a family group cognitive–behavioral preventive intervention with families of depressed parents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78(5):623–634. doi: 10.1037/a0020459. doi:10.1037/a0020459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compas BE, Forehand R, Thigpen J, Hardcastle E, Garai E, McKee L, Sterba S. Efficacy and moderators of a family group cognitive–behavioral preventive intervention for children of parents with depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2015;83(3):541. doi: 10.1037/a0039053. doi:10.1037/a0039053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyranowski JM, Frank E, Young E, Shear MK. Adolescent onset of the gender difference in lifetime rates of major depression - A theoretical model. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2000;57:21–27. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.57.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Dodge KA. Peer contagion in interventions for children and adolescents: Moving towards an understanding of the ecology and dynamics of change. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33(3):395–400. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-3579-z. doi:10.1007/s10802-005-3579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix T, Meunier LN. Depressive symptoms and parenting competence: An analysis of 13 regulatory processes. Developmental Review. 2009;29:45–68. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2008.11.002. [Google Scholar]

- England MJ, Sim LJ, editors. Depression in Parents, Parenting, and Children:: Opportunities to Improve Identification, Treatment, and Prevention. National Academies Press; 2009. doi:10.17226/12565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Foster CE, Webster MC, Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Rush AJ, King CA. Course and severity of maternal depression: Associations with family functioning and child adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2008;37(8):906–916. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9216-0. doi:10.1007/s10964-007-9216-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ. The Alabama Parenting Questionnaire. University of Alabama; Unpublished instrument, Tuscaloosa, AL: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Best KM, Conger RD, Simons RL. Parenting behaviors and the occurrence and co-occurrence of adolescent depressive symptoms and conduct problems. Developmental Psychology. 1996;32:717–731. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.32.4.717. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S, Rouse M, Connell A, Broth M, Hall C, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2011;14:1–27. doi: 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. doi:10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunlicks ML, Weissman MM. Change in child psychopathology with improvement in parental depression: A systematic review. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:379–389. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181640805. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e3181640805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammen C, Brennan PA, Shih JH. Family discord and stress predictors of depression and other disorders in adolescent children of depressed and nondepressed women. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:994–1002. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000127588.57468.f6. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000127588.57468.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin B, Fraley R, Lahey B, Waldman I. Is depression best viewed as a continuum or discrete category? A taxometric analysis of childhood and adolescent depression in a population-based sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:96–110. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.96. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.114.1.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Mermelstein R, Roesch L. Sex differences in adolescent depression: Stress exposure and reactivity models. Child development. 2007;78(1):279–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman S. The diagnosis of mental disorders: The problem of reification. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:155–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091532. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaser SS, Fear JM, Reeslund KL, Champion JE, Reising MM, Compas BE. Maternal sadness and adolescents’ responses to stress in offspring of mothers with and without a history of depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:736–746. doi: 10.1080/15374410802359742. doi:10.1080/15374410802359742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaser SS, Langrock AM, Keller G, Merchant MJ, Benson MA, Reeslund K, Compas BE. Coping with the stress of parental depression II: Adolescent and parent reports of coping and adjustment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34(1):193–205. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_18. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DJ, Forehand R, Rakow A, Colletti CJM, McKee L, Zalot A. The specificity of maternal parenting behavior and child adjustment difficulties: A study of inner-city African American families. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:181–192. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.181. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata Y, Alink L, Tseng W, IJzendoorn M, Crick N. Maternal and paternal parenting styles associated with relational aggression in children and adolescents: A conceptual analysis and meta-analytic review. Developmental Review. 2011;31:240–278. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2011.08.001. [Google Scholar]

- Klimes-Dougan B, Bolger AK. Coping with maternal depressed affect and depression: Adolescent children of depressed and well mothers. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1998;27(1):1–15. doi:10.1023/a:1022892630026. [Google Scholar]

- Lim J, Wood B, Miller B. Maternal depression and parenting in relation to child internalizing symptoms and asthma disease activity. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:264–273. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.264. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.22.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;29:561–592. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. doi:10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luster T, Okagaki L. Parenting: An ecological perspective. Vol. 2. Routledge; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Colletti C, Rakow A, Jones D, Forehand R. Parenting and child externalizing behaviors: Are the associations specific or diffuse? Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2008;13:201–215. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.005. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee L, Forehand R, Rakow A, Reeslund K, Roland E, Hardcastle E, Compas B. Parenting specificity. An examination of the relation between three parenting behaviors and child problem behaviors in the context of a history of caregiver depression. Behavior Modification. 2008;32(5):638–658. doi: 10.1177/0145445508316550. doi:10.1177/0145445508316550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKee LG, Jones DJ, Forehand R, Cueller J. Assessment of parenting style, parenting relationships, and other parenting variables. In: Saklofski D, editor. Handbook of psychological assessment of children and adolescents. Oxford University Press; New York: 2013. pp. 788–821. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199796304.013.0035. [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Weisz JR, Wood JJ. Examining the association between parenting and childhood depression: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:986–1003. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.001. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMahon RJ, Wells KC, Kotler JS. Conduct problems. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Treatment of childhood disorders. 3rd Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 137–268. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD, Book R, Rueter M, Lucy L, Repinski D, Scaramella L. The Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales. 5th Unpublished manuscript, Institute for Social and Behavioral Research, Iowa State University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Monroe SM, Simons AD. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders. Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110(3):406–425. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine . Depression in parents, parenting, and children: Opportunities to improve identification, treatment and prevention. The National Academies; Washington, DC: 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldehinkel AJ, Veenstra R, Ormel J, de Winter AF, Verhulst FC. Temperament, parenting, and depressive symptoms in a population sample of preadolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:684–695. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01535.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesenti-gritti P, Spatola CA, Fagnani C, Ogliari A, Patriarca V, Stazi MA, Battaglia M. The co-occurrence between internalizing and externalizing behaviors. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;17:82–92. doi: 10.1007/s00787-007-0639-7. M. doi:10.1007/s00787-007-0639-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe DC, Kandel D. In the eye of the beholder? Parental ratings of externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25(4):265. doi: 10.1023/a:1025756201689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman M, Reivich K, Jaycox L, Gillham J. The Optimistic Child. Houghton Mifflin; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sheeber L, Davis B, Hops H. Children of depressed parents: Mechanisms of risk and implications for treatment. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2002. Gender-specific vulnerability to depression in children of depressed mothers; pp. 253–274. doi:10.1037/10449-010. [Google Scholar]

- Shih JH, Eberhard NK, Hammen C, Brennan PA. Differential exposure and reactivity to interpersonal stress predict sex differences in adolescent depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2006;35:103–115. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_9. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3501_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg JL, Rutter M, Eaves L. Genetic and environmental influences on the temporal association between earlier anxiety and later depression in girls. Biological Psychiatry. 2001;49:1040–1049. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01161-1. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steer R, Brown G, Beck A, Sanderson W. Mean Beck Depression Inventory-II scores by severity of major depressive episode. Psychological Reports. 2001;88:1075–1076. doi: 10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3c.1075. doi:10.2466/pr0.2001.88.3c.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson S, Durbin E. Effects of paternal depression on fathers’ parenting behaviors: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2010;30:167–180. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.007. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M. Vulnerability to psychopathology: A biosocial model. Washington DC. 1999 doi:10.1037/10316-000. [Google Scholar]