INTRODUCTION

Postpartum haemorrhage is a dreaded complication. Survival depends upon immediate surgical control of the bleeding, medical management in the form of uterotonic drugs and rapid, effective transfusion therapy aimed at correction of intravascular blood volume.1, 2 Fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) by itself too has a high mortality rate and the presence of severe coagulopathy is common in these patients.3, 4 Pregnancy in a patient of FHF has a higher incidence of mortality because of haemorrhage in the setting of coagulopathy. There have been recent reports in literature outlining the benefits of recombinant factor VIIa in obstetric disasters.5, 6

We describe here a case of pregnancy with antepartum haemorrhage, FHF, severe coagulopathy and grade I encephalopathy who was taken up for a caesarian section, developed postoperative haemorrhage and massive blood loss. To stem the bleeding, she was managed with transfusion of blood components followed by recombinant factor VIIa.

CASE REPORT

The patient, a 31-year-old third gravida weighing 60 Kg, with history of one previous abortion reported at 38 weeks gestation with a breech presentation and complaints of progressive jaundice. On examination, she was haemodynamically stable, was icteric, had a grade I encephalopathy and anasarca. The liver was not palpable and she had deranged liver functions and coagulation profile (Table 1). Titres of IgG anti-HAV, IgM anti-HEV and HBsAg were negative. Ultrasonography (USG) revealed a normal liver with no evidence of fatty infiltration.

Table 1.

Investigation chart.

| At admission | After first surgery | Before first dose of rFVIIa | After rFVIIa | After second surgery and second dose of rFVIIa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hb (g/dL) | 14 | 9 | 6.6 | − | 10 |

| Serum bilirubin (mg/dL) | 14 | 11.4 | − | − | 13 |

| AST/ALT (U/L) | 104/394 | 334/72 | − | − | − |

| Prothrombin time (sec) | 12/23 | 12/30 | 12/40 | 12/15 | 12/9.7 |

| INR | 2.6 | 4 | 6 | 1.3 | 0.73 |

| PTTK (sec) | 30/40 | 30/38 | 30/62 | 30/33 | 30/29 |

| Platelet count (mm3) | − | 140,000 | 40,000 | 80,000 | 98,000 |

| FDP (ng/dL) | 6 | − | − | > 80 | |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 275 | − | 200 | − | 120 |

| D dimer (ng/dL) | 6 | − | 8 | > 40 |

Hb: haemoglobin, AST: aspartate aminotransferase, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, INR: international normalized ratio, PPTK: prothrombin time with activated thromboplastin with kaolin, FDP: fibrin degradation products.

The patient was diagnosed as pregnancy with acute liver failure and coagulopathy and was managed conservatively with injection vitamin K 10 mg i.v. daily and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) transfusions.

After two days she started bleeding per vaginum with a blood loss of approximately 800 mL over one hour. She became hypotensive, had tachycardia and an emergency caesarean section was planned. The patient was accepted for anaesthesia in ASA (The American Society of Anesthesiologists) grade IVE.

In view of generalised swelling peripheral vascular access could not be established and the right internal jugular vein was cannulated under FFP cover, central venous pressure was found to be 6 cm of water.

Rapid sequence induction with propofol in a sleep dose and succinylcholine was carried out. A live male baby was extracted following which the uterus remained atonic with persistent bleeding despite administration of methyl ergometrine, oxytocine infusion, intramuscular, and intrauterine injections of prostaglandin and therefore, as a last resort, obstetric hysterectomy was performed.

Her vitals parameters stabilised with an approximate intra-operative blood loss of 1,500 mL being replaced with three packed red blood cells (PRBC), six units each of FFP and cryoprecipitate and fluids (3,000 mL normal saline solution, and 500 mL of Voluven® [6% hydroxyethyl starch 130/0.4 in 0.9% sodium chloride injection]). The central venous pressure (CVP) was maintained between 12 cm and 14 cm of water and the urine output was 300 mL intra-operatively.

In view of encephalopathy and poor lung compliance she was shifted to intensive care unit (ICU) for elective ventilation and kept sedated and paralysed. Postoperatively investigations showed a deranged coagulation profile and anaemia (Table 1). A central venous blood gas analysis was carried out which showed: pH 7.46, PaCO2 31 mmHg, PaO2 41 mmHg, HCO3 21 mmol/L, and O2 sat 81%. Two PRBCs, six FFPs, and 250 mL of 20% albumin were transfused.

Over the next eight hours, she remained stable although the pulse rate showed an upward trend with the CVP staying between 3 cm and 6 cm of water. The abdominal drains had collected 1,675 mL of blood and lab investigations showing anaemia, thrombocytopenia, and coagulopathy (Table 1). One pack of single donor platelets, six units of FFP, and five units of PRBC were transfused. In view of continued bleeding in spite of a total of eight units of PRBC, 14 units of FFP, six units of cryoprecipitate and one unit of single donor platelets, in the absence of hypothermia and acidosis, 4.8 mg of recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) at 80 μg/Kg was injected intravenously over three minutes after reconstitution by the bed side. There was a dramatic correction of the prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) (Figure 1, Figure 2). She remained stable over the next six hours. However, thereafter, there was a rapid collection of frank blood in the abdominal drains (750 mL) with hypotension and ooze from puncture sites. Moreover, she was showing features of early disseminated intravenous coagulopathy (DIC) with fibrin degradation products (FDP) > 80 ng/dL and D Dimers > 40 ng/dL and a drop in the platelet counts to 40,000/mm3 though her PT was C – 13s T – 19s INR 1.5 aPTT C – 30s T – 36s. The haemoglobin was 7 g/dL in spite of the blood transfusions. An emergency bed side ultrasound examination showed an intra-abdominal collection. In view of the fresh findings, it was decided to take the patient up for emergency re-exploration to rule out any surgical cause of the bleeding as also for peritoneal toilette.

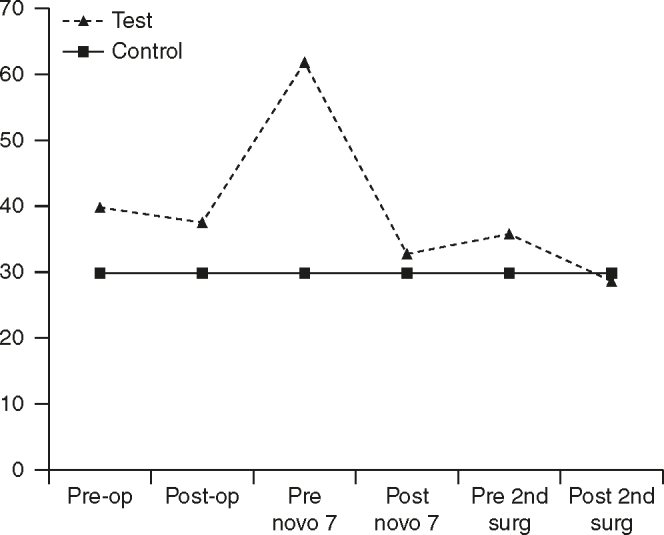

Figure 1.

International normalized ratio values. Pre-op: pre-operative day; Post-op: postoperative day.

Figure 2.

Activated partial thromboplastin time profile. Pre-op: pre-operative day; Post-op: postoperative day.

She was accepted for anaesthesia in ASA grade VE. General anaesthesia was administered, she remained haemodynamically stable intra-operatively. During surgery a collection of approximately 3,200 mL blood and clots were removed from the abdominal cavity, there was no active surgical bleeding but a generalised ooze was present.

The internal iliac arteries on both sides were ligated; the pelvis was sprayed with fibrin glue. Blood component replacement with six units each of PRBC, cryoprecipitate, platelet rich plasma, and one unit of single donor platelets was carried out. Further, 2.4 mg IV rFVIIa at 40 μg/Kg1 was also administered prior to closing the abdomen. The same dose was repeated intravenously after one hour of surgery after confirming the absence of hypothermia or metabolic acidosis. She was ventilated postoperatively in view of severe hypoxia with poor lung compliance.

By the evening, there was an improvement in coagulopathy, haemoglobin and platelet counts (Table 1). No more blood products were transfused for the next 12 hours after which the laboratory investigations showed: Hb 10.0 g/dL%, platelets 60,000/mm3, PT C12s T-22s INR – 2.4, serum bilirubin 13 mg/dL, venous blood gas pH 7.5, O2 sat 98%.

She was administered FFP and platelets intermittently thereafter in addition to a broad spectrum antibiotics and made a gradual recovery. She was weaned off ventilatory support by the sixth day and extubated.

DISCUSSION

Recombinant activated factor VIIa enjoys Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for the treatment of bleeding in patients with haemophilia A or B with inhibitors to factor VIII or IX. In the past few years, there are a number of case reports of its successful, empirical, out-of-licence, “compassionate use”7 rFVIIa has also been used for severe PPH to good effect.8, 9, 10, 11 Compassionate use of factor VII directs that it may be used only as a last resort once other means to control massive bleeding have been exhausted.7, 12 Therefore, all efforts to correct coagulopathy in our patient were made by conventional means. Factor VIIa was used for the first time only at this stage.

There are now numerous reports of the prophylactic use of factor VII in patients of liver failure to correct the coagulopathy prior to surgical procedures.13, 14, 15 Among the earliest case series published in this area,5 91.7% of cases of severe PPH treated with rFVIIa in addition to standard surgical and medical interventions showed a good response. Interestingly, the authors recorded a learning curve in the use of rFVIIa for surgeons and anaesthesiologists: in the first part of the study the average use of blood products before the use of rFVIIa was 67.6 units, but only 37.2 units in the second part of the study, indicating that rFVIIa was being administered earlier in the bleeding episodes.

Other authors16, 17 have concluded that the use of rFVIIa may allow not only to decrease the number of blood products administered, but also to avoid a hysterectomy if used more rapidly. They have shown that of 27 PPH cases treated with rFVIIa uterine atony was responsible for 82% of PPH cases. At a median dose of 79 mg/Kg (range 16–128 mg/Kg), rFVIIa was effective in avoiding emergency hysterectomy in 16 of 21 cases (76%), and led to a relevant reduction or complete cessation of bleeding in 24 of 27 cases (89%).

In a another comprehensive review article, the authors have considered the use in patients with liver disease and active bleeding as promising and they too have touched on the dilemma of whether the drug should be administered early or late.18

In our patient, the time frame of about 12 hours between the first surgery and the time to administration of rFVIIa when it was attempted to stem the bleeding by conventional methods resulted in collection of 3.2 L of blood in the abdominal cavity despite drains being in situ. Though there was a dramatic correction of the coagulation parameters it is evident that by this time early DIC was setting in more so because of the large collection of blood in the abdominal cavity. During the second surgery once the collected blood was removed and rFVIIa administered just prior to closure of the abdomen after infusing adequate blood components the bleeding became significantly less allowing the patient to recover uneventfully.

In hind sight, early use of rFVIIa to control the coagulopathy prior to the emergency caesarian section may have avoided the requirement of hysterectomy, subsequent continued bleeding, as also requirement of the second dose of rFVIIa. Thus, indicating that there may be a role for the pre-/intra-operative use of rFVIIa in the pregnant patient with liver failure, coagulopathy, and massive bleeding being taken up for emergent surgery.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mousa HA, Walkinshaw S. Major postpartum haemorrhage. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2001;13:595–603. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200112000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Macphail S, Talks K. Massive postpartum haemorrhage and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;14:123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiodt FV, Atillasoy E, Shakil AO. Etiology and outcome for 295 patients with acute liver failure in the United States. Liver Transpl Surg. 1999;5:29–34. doi: 10.1002/lt.500050102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pereira SP, Langley PG, Williams R. The management of abnormalities of hemostasis in acute liver failure. Semin Liver Dis. 1996;16:403–414. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ahonen J, Jokela R. Recombinant factor VIIa for life-threatening postpartum haemorrhage. Br J Anaesth. 2005;94:592–595. doi: 10.1093/bja/aei094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zupanic SS, Sokolic V, Viskovic T, Sanjug J, Simic M, Kastelan M. Successful use of recombinant factor VIIa for massive bleeding after caesarian section due to HELLP syndrome. Acta Haematol. 2002;108:162–163. doi: 10.1159/000064699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martinowitz U, Michaelson M, on behalf of the Israeli Multidisciplinary rFVIIa Task Force Guidelines for the use of recombinant activated factor VII (rFVIIa) in uncontrolled bleeding: a report by the Israeli multidisciplinary rFVIIa task force. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:640–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobieszczyk S, Breborowicz G. Management recommendations for postpartum hemorrhage. Arch Perinat Med. 2004;10:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincent JL, Rossaint R, Riou B, Ozier Y, Zideman D, Spahn DR. Recommendations on the use of recombinant activated factor VII as an adjunctive treatment for massive bleeding-a European perspective. Crit Care. 2006;10:R120. doi: 10.1186/cc5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welsh A, McLintock C, Gatt S, Somerset D, Popham P, Ogle R. Guidelines for the use of recombinant activated factor VII in massive obstetric haemorrhage. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;48:12–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2007.00823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franchini M, Franchi M, Bergamini V. The use of recombinant activated FVII in postpartum haemorrhage. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010;53:219–227. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181cc4378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spivey M, Parr MJA. Therapeutic approaches in trauma-induced coagulopathy. Minerva Anestesiol. 2005;71:281–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedner U. Recombinant activated factor VII as a universal haemostatic agent. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 1998;9:S147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jeffers L, Chalasani N, Balart L, Pyrsopoulos N, Erhardtsen E. Safety and efficacy of recombinant factor VIIa in patients with liver disease undergoing laparoscopic liver biopsy. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:118–126. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anantharaju A, Mehta K, Mindikoglu AL, Van Thiel DH. Use of activated recombinant human factor VII (rhFVIIa) for colonic polypectomies in patients with cirrhosis and coagulopathy. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48:1414–1424. doi: 10.1023/a:1024144217614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boehlen F, Morales MA, Fontana P, Ricou B, Irion O, de Moerloose P. Prolonged treatment of massive postpartum haemorrhage with recombinant factor VIIa: case report and review of the literature. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;111:284–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouma LS, Bolte AC, van Geijn HP. Use of recombinant activated factor VII in massive postpartum haemorrhage. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;137:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levi M, Peters M, Büller HR. Efficacy and safety of recombinant factor VIIa for treatment of severe bleeding: a systematic review. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:4. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000159087.85970.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]