INTRODUCTION

Intestinal lipomas (IL) are benign, slow-growing mesenchymal neoplasms arising from adipose connective tissue in the bowel wall. The incidence of IL is between 0.035% and 4.4% in large autopsy series while colonoscopy studies put the incidence at between 0.11% and 0.15%.1, 2 The majority of IL are small and asymptomatic. Larger lesions may be symptomatic and also cause radiological and endoscopic confusion with malignancy.3 We report a series of cases of symptomatic IL which were successfully managed surgically.

CASE REPORTS

The first case was a 54-year-old male who presented with colicky right abdominal pain of one month duration. Clinically he had an ill-defined 18 × 6 cm2 lump in the right lumbar region and iliac fossa. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of abdomen showed a non-uniform wall thickening with narrowed lumen of the caecum and the ascending colon up to the hepatic flexure along with loss of fat plane with the liver, suggestive of locally infiltrative colonic malignancy (Figure 1). Colonoscopy demonstrated a large polypoidal lesion extending from the ileo-caecal valve to the hepatic flexure. Endoscopic biopsy failed to reveal the diagnosis. At laparotomy, an irreducible ileo-colic intussusception was found and a right hemicolectomy was done. The intussusception was caused by a large polypoidal mass arising from the terminal ileum (Figure 2). Histopathological examination (HPE) confirmed fatty tissue with no evidence of malignancy.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography of abdomen showing the non-uniform wall thickness with irregular narrowing of the lumen of the ascending colon.

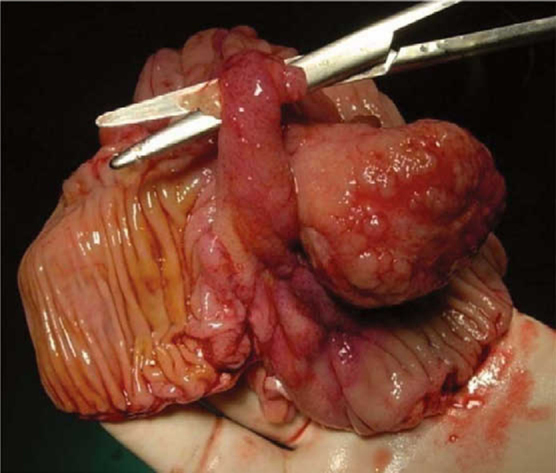

Figure 2.

Intussusception across the ileo-caecal valve caused by a large lipoma arising from the terminal ileum.

The second case was a 23-year-old lady who presented first with watery diarrhoea and later with colicky pain left lower abdomen associated with bleeding per rectum. Colonoscopy revealed a large polyp almost occupying 50% of the lumen of the sigmoid and the descending colon. An intussusception was encountered when the scope was negotiated beyond the polyp. Biopsy was taken which suggested fatty tissue. The CECT of abdomen confirmed the colo-colic intussusception with lipoma as a lead point. Intra-operatively a large lipoma from the descending colon had caused the colo-colic intussusception (Figure 3). The patient underwent a left colectomy with stapled colo-colic anastomosis. Histopathological examination confirmed the lipoma.

Figure 3.

Resected specimen cut open to show the lipoma as the lead point for the intussusception.

The third case was a 73-year-old lady who presented with subacute intestinal obstruction. Clinically, the abdomen was soft and distended. Digital rectal examination revealed a large mass occupying the whole of the rectum. Sigmoidoscopy showed a large ball-like mass with ulcerated surface. The CECT of abdomen revealed a thick walled rectum and sigmoid colon with soft tissue density lesion in the recto-sigmoid junction causing luminal narrowing. At surgery, there was a large polypoidal mass arising from the sigmoid colon and causing a colo-rectal intussusception (Figure 4). Sigmoid colectomy with colo-rectal anastomosis was done. The patient recovered uneventfully. Histopathological examination revealed colonic lipoma.

Figure 4.

Resected submucosal lipoma causing intussusception.

DISCUSSION

Bauer first described lipoma of the colon in 1757.4 These lipomas occur in elderly people (average age 60 years).3 In our series of three cases, one was young at 23 years of age while the other two presented were above 50 years of age. Almost 70% of these lipomas are localised in the right hemi-colon; the caecum, ascending and transverse colon in decreasing order of frequency.1 Our series had two cases of left colon and the third from the distal ileum. Men have a slightly increased propensity towards left-sided lesions.2 Pathologically, IL are well differentiated and arise from adipose connective tissue in the bowel wall. Almost, 90% are submucosal in origin. The rest are either subserosal or intramuscular.3

They are usually solitary with varying sizes and may be sessile or pedunculated.3 All three cases in our series had pedunculated lesions. Majority of these lesions are asymptomatic or detected incidentally during the examination of symptoms like abdominal pain, change in bowel habits, rectal bleeding or in surgical specimen removed for various other reasons.2, 5 The severity of signs and symptoms is attributed to the size of the lesions. Lipomas > 2 cm in diameter may be symptomatic.5 On rare occasions, IL may present with massive haemorrhage, obstruction, perforation, intussusception, or prolapse.5 All lipomas in our cases were > 2 cm in size and all were symptomatic. Intussusception was present in all cases. One patient had associated rectal bleeding.

In practice, the diagnosis of IL and its complications as well as distinguishing them from the more common premalignant polyp or frank malignancy can often be challenging.6 Various investigative modalities like barium enema, ultrasound, CT scans, and colonoscopy can be helpful. At barium enema the most important diagnostic feature of the lipoma is that the tumour can deform by peristalsis “squeeze sign”.7 The use of ultrasound is limited due to the presence of gas in the bowel.8 CT can diagnose IL with relative certainty due to its uniform appearance and density and the negative Hounsfield unit (HU: –50).9

Although colonoscopy gives the best view of the lesion, it may be difficult to take a biopsy of the adipose tissue lying beneath normal mucosa.1 Probing with closed biopsy forceps producing a keyhole through which biopsy can be taken is sometimes possible. Other features on colonoscopy include the “tenting” sign, where the mucosa tents over the lesion when grasped with forceps, the “cushion” sign, where flattening of the lesion is followed by restoration of its shape on pressure being removed, and the “naked fat” sign, where adipose tissue discharges from the mucosal defect following biopsy.1

Treatment of IL is varied and debatable. Small and asymptomatic lipomas require no treatment.10 Intervention is required for symptomatic IL or for HPE in case of diagnostic dilemma. Elective endoscopic removal of submucosal lipoma < 2 cm in diameter is reported to be safe and appropriate; however, in larger lesions the risk of complications like haemorrhage and perforation makes the procedure controversial.9 For lesions > 2 cm, surgical resection seems to be the ideal especially when malignancy cannot be completely excluded.10 Surgical intervention is also mandatory in emergencies like obstruction, intussusception, perforation, or very rarely massive haemorrhage. In conclusion, IL are an uncommon cause for intestinal obstruction and haemorrhage. Clinical recognition is vital for distinction from premalignant lesions and treatment.

REFERENCES

- 1.El Tinay OY, Khan IR, Noureldin OH, Al Boukai AA. Caecal lipoma causing colo-colonic intussusception. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:145–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Montgomery DA, Reidy J. Giant submucosal colonic lipomata: report of a case and review of the literature. SMJ. 2004;49:71. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franc-Law JM, Begin LR, Vasilevsky CA, Gordon PH. The dramatic presentation of colonic lipomata: report of two cases and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2001;67:491–494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Haller JD, Roberts TW. Lipomas of the colon: a clinico-pathologic study of 20 cases. Surgery. 1964;55:773–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katsinelos P, Chatzimavroudis G, Zavos C, Paroutoglou G, Papaziogas B, Kountouras J. A novel technique for the treatment of a symptomatic giant colonic lipoma. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:467–469. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.0208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim CY, Bandres D, Tio TL, Benjamin SB, Al-Kawas FH. Endoscopic removal of large colonic lipomas. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:929–931. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.124098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alponat A, Kok KYY, Gob PMY, Ngoi SS. Intermittent subacute intestinal obstruction due to a giant lipoma of the colon: a case report. Am Surg. 1996;62:918–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wissbage DL, Scheible W, Leopold JR. Ultrasonic appearance of adult intussusception. Radiology. 1997;124:791–792. doi: 10.1148/124.3.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung YF, Ho YH, Nyam DC, Leong AF, Seow-Choen F. Management of colonic lipomas. Aust NZ J Surg. 1998;68:133–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1998.tb04723.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Cong JC, Chen CS, Qiao L, Liu EQ. Submucous colon lipoma: a case report and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:3167–3169. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i20.3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]