INTRODUCTION

Epidermolysis bullosae (EB) is a rare group of inherited disorders that manifest as blister or erosion of the skin and in some cases the epithelial lining of other organs, in response to little or no apparent trauma. Mild variants have been estimated to occur as frequently as 1 per 50,000 births. More severe varieties are believed to occur in 1 per 500,000 births annually. “Butterfly children” is a term often used to describe younger patients because the skin is said to be as fragile as a butterfly's wings.1 The following major types (based on the precise ultra-structural level at which the split responsible for blistering occurs) of EB have been identified:

-

(a)

Epidermolytic: Epidermolysis bullosa simplex (EBS)

-

(b)

Lucidolytic: Junctional epidermolysis bullosa (JEB)

-

(c)

Dermolytic: Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB)1

Although examination of skin biopsy is often required to establish the diagnosis, it may not be necessary in few babies, especially those with a positive family history, who have blisters on the palms and soles only. Here we report a case of EB in a newborn baby. The case is reported to heighten the clinical awareness of this condition.

CASE REPORT

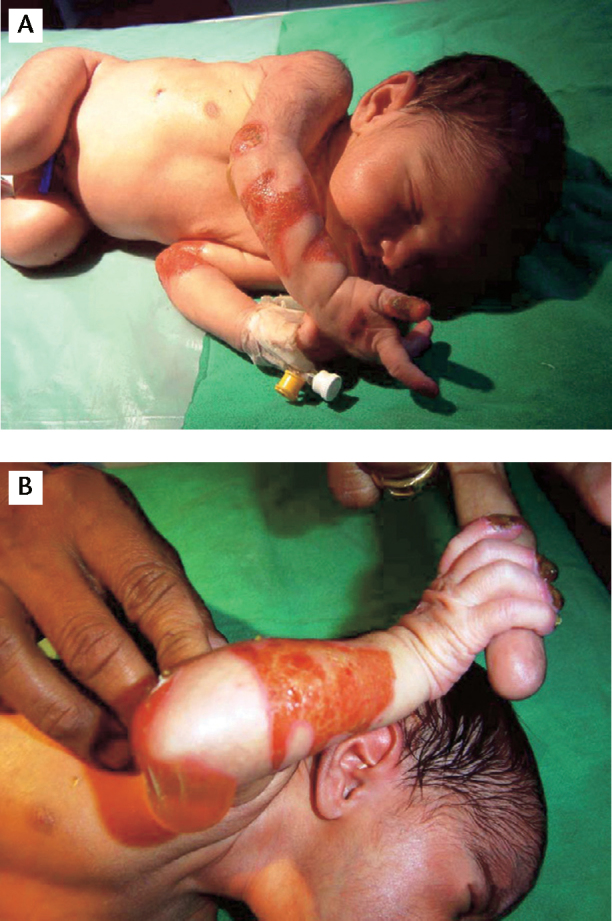

A 37-weeks term female baby was born with characteristic skin rashes. The baby was born to a primigravida mother, out of non-consanguineous marriage. The skin of the baby was eroded and fresh granulation tissues were present over the extensor aspects of both elbows and buttocks. Over the next few days, new lesions appeared, in the form of blisters and peeling of skin over various other body parts, especially the diaper area and parts more prone to friction and rubbing (Figure 1). Blisters were filled with clear straw-coloured fluid and varied in size from 1 mm to 5 cm in diameter. Fingers and toes were affected with dystrophic and eroded nails. There were no other associated defects and other systemic examination was normal. Limb and body movements were complete and sucking was effective and normal. A clinical diagnosis of EBS was made. Screening test for congenital syphilis was negative. Skin biopsy (using electron microscopy) from the edge of affected lesion confirmed it to be EBS. There was no similar family history in the past. Supportive management in the form of skin dressing, puncture of blisters, local antiseptic application and careful handling was done. Complete breast feeds was started and genetic counselling was done. The baby is progressing well on regular OPD follow-up.

Figure 1(A, B).

Typical features of epidermolysis bullosa with skin blisters and erosions involving the areas more prone for rubbing and trauma.

DISCUSSION

Epidermolysis bullosae is a genetic disorder caused by a mutation in the keratin gene. The identified genes include those that encode keratins 5 and 14 in EBS (autosomal recessive), collagen VII in DEB (autosomal recessive and dominant types), and laminin 5 in Herlitz JEB (autosomal dominant).2 The exact prevalence of EB is unknown. Worldwide, an estimated 50 in 1 million live births are diagnosed with EB, and 9 in 1 million are in population. Of these cases, approximately 92% are EBS, 5% are DEB, 1% is JEB, and 2% are unclassified.3 Incidence in India is estimated to be 54 per million live births (according to National Epidermolysis bullosa Registry).4

The disorder is characterised by the presence of extremely fragile skin and recurrent blister formation, resulting from minor mechanical friction or trauma. Depending on the type of EB, disease severity may range from occasional mild blistering of the hands and feet to severe and widespread formation of bullae. Areas prone to blistering due to pressure, trauma, or excessive heating include the fingers, hands, elbows, feet, legs, and diaper area (in infants). These lesions may result in nonhealing erosions, infection, scarring, and joint contracture (Table 1). Symptoms depend on the type of EB but can include hoarse cry, cough, alopecia, blistering around the eyes and nose, blistering in or around the mouth and throat causing feeding or swallowing difficulty, dental abnormalities such as tooth decay, nail loss or deformed nails.1, 3 Death may occur during infancy or early childhood due to sepsis, renal failure, upper airway occlusion, or failure to thrive (due to oesophageal stricture).5, 6

Table 1.

Comparing the clinical features of three major types of epidermolysis bullosa.

| Type | Onset | Clinical features |

|---|---|---|

| EBS | At birth or early infancy | Blisters develop all over the body but commonly on hands, feet, and extremities (frictional areas) |

| JEB | At birth | Generalised and severe form, where blisters appear all over the body and often involve mucous membranes and internal organs |

| DEB | At birth or early childhood | Generalised severe blistering is more common and involves large areas of skin and mucous membranes. |

| Can be localised in frictional areas |

EBS: epidermolysis bullosa simplex, JEB: junctional epidermolysis bullosa, DEB: dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa.

Skin biopsy light microscopy examination in EBS reveals separation and blister formation in the epidermal layer (keratinocytes). Examination by immunofluorescent antibody/antigen mapping is the sine qua non for the diagnosis of EBS because of its rapid turnaround time, and high sensitivity and specificity.7 Transmission electron microscopic examination may also be used to identify tonofilament clumping and further delineate the classification of EBS. The leading edge of a mechanically induced blister with some normal adjacent skin should be biopsied as older blisters undergo change that may obscure the diagnostic morphology. In all cases of EBS, splitting is observed within or just above the basal cell layer of the skin.7

Supportive care to protect the skin from blistering, appropriate dressings that will not further damage the skin and will promote healing, and prevention and treatment of secondary infection are the mainstay of EB treatment.8 Dressings involve three layers: a primary non-adherent dressing, a secondary layer providing stability and adding padding, and a tertiary layer with elastic properties.9 Aluminium chloride (20%) applied to palms and soles can reduce blister formation in some individuals. Keratolytics and softening agents for palmer plantar hyperkeratosis may prevent tissue thickening and cracking. Surveillance for wound infection is important and treatment with topical and/or systemic antibiotics or silver-impregnated dressings or gels can be helpful. Additional nutritional support may be required for failure to thrive in infants and children with EBS who have more severe involvement. Management of fluid and electrolyte problems is critical, as they can be significant and even life-threatening in the neonatal period and in infants with widespread disease.

To prevent skin trauma and blistering, it may be helpful to wear padding around trauma-prone areas such as the elbows, knees, ankles, and buttocks. Contact sports should be avoided. Genetic counselling should be done in affected cases.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): Report of the Third International Consensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:931–950. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGrath JA, Mellerio JE. Epidermolysis bullosa. Br J Hosp Med. 2006;67:188–191. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2006.67.4.20864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marinkovich MP, Herron GS, Khavari PA, Bauer EA. Inherited epidermolysis bullosa. In: Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 6th ed. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 2003. pp. 596–609. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grover S. Generalised recessive dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa in two sisters. IJDVL. 2001;67:205–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Risser J, Lewis K, Weinstock MA. Mortality of bullous skin disorders from 1979 through 2002 in the United States. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1005–1008. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fine JD, Johnson LB, Weiner M, Suchindran C. Cause-specific risks of childhood death in epidermolysis bullosa. J Pediatr. 2008;152:276–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yiasemides E, Walton J, Marr P, Villanueva EV, Murrell DF. A comparative study between transmission electron microscopy and immunofluorescence mapping in the diagnosis of epidermolysis bullosa. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:387–394. doi: 10.1097/01.dad.0000211510.44865.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mellerio JE, Weiner M, Denyer JE. Medical management of epidermolysis bullosa: Proceedings of the Second International Symposium on Epidermolysis Bullosa, Chile, 2005. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:795–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2007.03316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bello YM, Falabella AF, Schachner LA. Management of epidermolysis bullosa in infants and children. Clin Dermatol. 2003;21:278–282. doi: 10.1016/s0738-081x(03)00050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]