INTRODUCTION

Androgen receptor (AR) sensitivity is an important determinant in full expression of male phenotype in an XY individual at two stages of life, intrauterine life as well as at puberty.

The androgen insensitivity syndrome (AIS) represents a spectrum of disorders where the degree of receptor insensitivity varies from minimal to complete insensitivity.1, 2 In case of minimal androgen insensitivity (MAIS), the individual is a phenotypically male with male sterility, azoospermia, and gynaecomastia. The other end of the spectrum includes XY individuals who have complete androgen insensitivity and they present as tall phenotypically females with well-developed breasts, blind vagina, and absent or scanty pubic and axillary hair.1

It is the middle of the spectrum of androgen insensitivity; the partial androgen insensitivity syndrome (PAIS), which is the most difficult to diagnose and presents as a diagnostic dilemma. Although these patients have an XY karyotype, they present with ambiguous genitalia at birth,1 impaired spermatogenesis1 with otherwise normal testis, absent or rudimentary mullerian structures,3 normal or increased synthesis of testosterone, normal or increased synthesis of luteinising hormone by pituitary,2 or defective androgen binding activity of genital skin fibroblasts.4

The estimated incidence of complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS) is one in 20,400 XY births,5 while the incidence of PAIS is one in 130,000 births.6

We present a case of a 26-year-old, who was born with ambiguous genitalia and had undergone feminising genitoplasty at the age of four years. She was raised as a girl and presented to us with features of masculinisation.

CASE REPORT

The patient, a 26-year-old female, working as a sports teacher in a girl's school, presented to us in the outpatient department with gradual onset of features of masculinisation over the past eight years. She was fifth in order of birth and was of average height compared to her siblings. A detailed history revealed that she was born with ambiguous genitalia for which medical help was taken by her parents at the age of four years. Medical records at that age revealed penoscrotal hypospadias, with length of phallus around 2.5 cm with no testis palpable in the inguinal region or groin. Investigations done 22 years back showed normal serum electrolytes and urinary 17-ketosteroids. Ultrasound and contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan of whole abdomen revealed a small hypoplastic uterus with no evidence of any intra-abdominal gonads. However, both kidneys and suprarenal's were normal. Barr body was present on the buccal mucosal smear and her karyotype revealed Turners' syndrome with mosaic pattern (45 XO/XX). She subsequently underwent vaginoplasty with clitoroplasty at the age of 4.5 years and was raised as a female.

At around the age of 13 years she was prescribed cyclic oestrogen and progesterone. Though she had breast development, she continued to have amenorrhoea and stopped taking hormones after a few years.

On examination, she was of average height and weight (height: 171 cm, weight: 65 Kg, BMI: 22.23). However, she had male type of body contour (Figure 1). Hirsutism was evident and her Ferriman Gallwey score was 21. Breasts were developed to Tanner's stage III. Axillary hairs were present and pubic hairs were developed to Tanner's stage IV. No lump was palpable on per abdominal examination and all hernial sites were free. Both the labia majora were seen, a 0.5 cm scar mark of previous surgery was visualised in between the labia anteriorly (Figure 2). Urethra was present 1 cm below the scar of clitoroplasty on the anterior vaginal wall, and vagina was just an inch long and ended blindly. Per rectally, uterus was not palpable. Her hormone profile revealed normal serum dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS), androstenedione, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels (410 μg/dL, 1.02 ng/mL, 0.63 ng/mL, respectively). However, she had high serum testosterone levels (109 ng/dL, normal adult male 200–800 ng/dL, adult female 20–80 ng/dL) and low serum oestradiol (16 pg/mL) for an adult female. Serum LH (19.6 mIU/mL) and serum FSH (26.3 mIU/mL) were also raised. Neither gonads nor uterus was visualised on ultrasound pelvis. A repeat karyotype was ordered which revealed 46XY, with no numerical or structural chromosomal anomalies.

Figure 1.

Masculine facies.

Figure 2.

External genitalia.

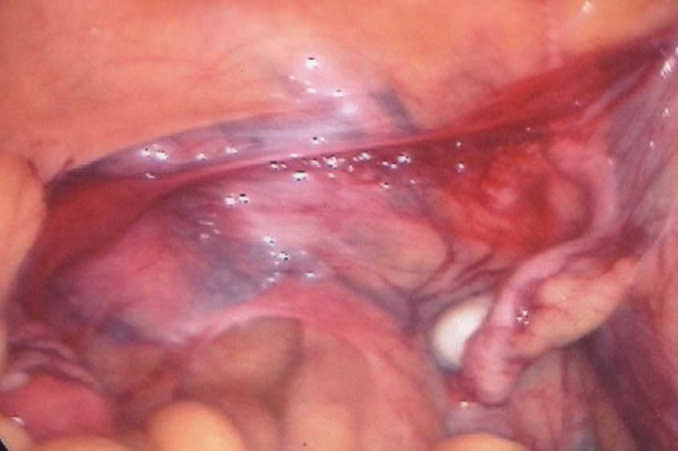

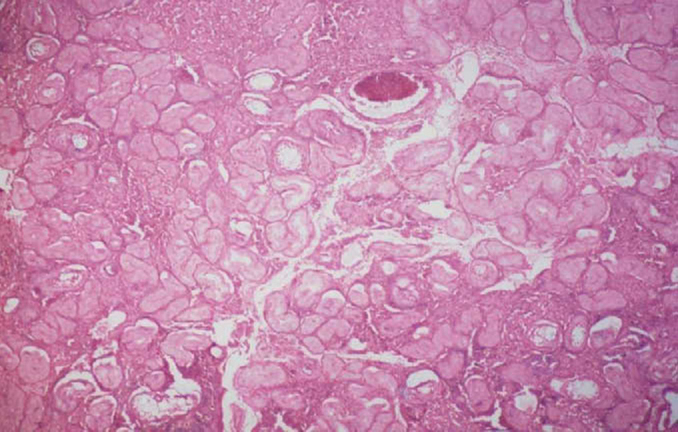

A diagnostic laparoscopy with bilateral gonadectomy was then performed on the patient. Per-operatively, bilateral gonads with fallopian tubes were visualised. However, the tubes were connected by a fibrous band with a bulbous swelling on the left side which appeared like left rudimentary horn of the uterus (Figure 3). The histopathology report of the gonads was reviewed in the department of pathology, Base Hospital, Delhi Cantt. It revealed Leydig cell proliferation, atrophic seminiferous tubules with no evidence of any ovarian tissue, hence, confirming the gonads as testis (Figure 4, Figure 5). The tubular structure was confirmed as fallopian tubes on histopathology report. Hence, a diagnosis of PAIS was made. Her serum testosterone levels postoperatively at six weeks had fallen to 3.8 ng/dL. She has been advised hormone replacement therapy (HRT), and is on close follow-up till date.

Figure 3.

Laparoscopic view.

Figure 4.

Leydig cell proliferation.

Figure 5.

Atrophic semniferous tubules.

DISCUSSION

Individuals with partial androgen insensitivity, unlike those with the complete or mild forms, present at birth with ambiguous genitalia, and the decision to raise the child as male or female is very difficult.1 They present with varying degrees of hypospadias, micropenis, bifid scrotum, with either descended or undescended testes, and gynaecomastia at puberty.1 It is transmitted as an X-linked trait and is related to the mutations in AR gene.

Management of AIS includes sex assignment, genitoplasty, gonadectomy in relation to tumour risk, HRT, and genetic and psychological counselling.

Key considerations involved in assigning gender include the appearance of the genitalia,7 the extent to which the child can virilise at puberty,2 surgical options and the postoperative sexual function of the genitalia,8, 9, 10 genitoplasty complexity9 and the projected gender identity of the child. The majority of individuals with PAIS are raised as male.1

Genitoplasty, unlike gender assignment, can be irreversible, and there is no guarantee that adult gender identity will develop as assigned despite surgical intervention.10 Points of consideration include what conditions justify genitoplasty, the extent and type of genitoplasty that should be employed, when genitoplasty should be performed and what should be the goals of genitoplasty.7, 10

Though feminising genitoplasty typically requires fewer surgeries to achieve an acceptable result and results in fewer urologic difficulties, there is no evidence that feminising surgery results in a better psychosocial outcome.10 Procedures include clitoral reduction/recession, labiaplasty, repair of the common urogenital sinus, vaginoplasty, and vaginal dilation through non-surgical pressure methods.7, 10

The outcome of masculinising genitoplasty is dependent on the amount of erectile tissue and the extent of hypospadias.7 Procedures include correction of penile curvature and chordee, reconstruction of the urethra, hypospadias correction, orchidopexy, and mammoplasty after puberty for correction of gynaecomastia.1

Gonadectomy at time of diagnosis is currently recommended for PAIS if presenting with cryptorchidism, due to the high (50%) risk of germ cell malignancy.7 Hormone replacement therapy is required after gonadectomy, and should be modulated over time to replicate the hormone levels naturally present in the body during the various stages of puberty.7

CONCLUSION

The cases of PAIS, present with ambiguous genitalia at birth and require detailed and deliberate evaluation to confirm their diagnosis. These children if reared as females as in our case, present with virilisation at the usual age of male puberty and have to be dealt with accordingly.

Though majority of the workers believe that they should be raised as males, however, a multidisciplinary approach with individualisation of every case is essential to reach the best possible outcome for a psychologically satisfying adulthood.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

None identified.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hughes IA, Deeb A. Androgen resistance. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20:577–598. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galani A, Kitsiou-Tzeli S, Sofokleous C, Kanavakis E, Kalpini-Mavrou A. Androgen insensitivity syndrome: clinical features and molecular defects. Hormones (Athens) 2008;7:217–229. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannema SE, Scott IS, Rajpert-De Meyts E, Skakkebæk NE, Coleman N, Hughes IA. Testicular development in the complete androgen insen-sitivity syndrome. J Pathol. 2006;208:518–527. doi: 10.1002/path.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ahmed SF, Cheng A, Hughes IA. Assessment of the gonadotrophin-gonadal axis in androgen insensitivity syndrome. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80:324–329. doi: 10.1136/adc.80.4.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lund A, Juvonen V, Lähdetie J, Aittomäki K, Tapanainen JS, Savontaus ML. A novel sequence variation in the transactivation regulating domain of the androgen receptor in two infertile Finnish men. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(Suppl 3):1647–1648. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00256-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bangsbøll S, Qvist I, Lebech PE, Lewinsky M. Testicular feminization syndrome and associated gonadal tumors in Denmark. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1992;71:63–66. doi: 10.3109/00016349209007950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahmed SF, Cheng A, Dovey L. Phenotypic features, androgen receptor binding, and mutational analysis in 278 clinical cases reported as androgen insensitivity syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:658–665. doi: 10.1210/jcem.85.2.6337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morel Y, Rey R, Teinturier C. Aetiological diagnosis of male sex ambiguity: a collaborative study. Eur J Pediatr. 2002;161:49–59. doi: 10.1007/s00431-001-0854-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes IA, Houk C, Ahmed SF, Lee PA, LWPES Consensus Group, ESPE Consensus Group Consensus statement on management of intersex disorders. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:554–563. doi: 10.1136/adc.2006.098319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ismail-Pratt IS, Bikoo M, Liao LM, Conway GS, Creighton SM. Normalization of the vagina by dilator treatment alone in complete androgen insensitivity syndrome and Mayer-Rokitansky-Kuster-Hauser syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2020–2024. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]