Abstract

Diarrheal diseases are a major cause of childhood death in resource-poor countries, killing about 760, 000 children under age 5 each year. While deaths due to diarrhea have declined dramatically, high rates of stunting and malnutrition have persisted. Environmental Enteric Dysfunction (EED) is a subclinical condition caused by constant fecal-oral contamination with resultant intestinal inflammation and villous blunting. These histological changes were first described in the 1960’s but the clinical impact of EED is only just being recognized in the context of failure of nutritional interventions and oral vaccines in resource-poor countries. We review the existing literature regarding the underlying causes of and potential interventions for EED and poor growth in children, highlighting the epidemiology, clinical and histologic classification of the entity, as well as discussing novel biomarkers and possible therapies. Future research priorities are also discussed.

Keywords: malnutrition, diarrheal diseases, environmental enteric dysfunction, interventions

Introduction

Enteric infections and diarrheal diseases are the second leading cause of death in children < five years old world-wide, causing approximately 760, 000 annual deaths (1). Diarrhea is inextricably interlinked with malnutrition and is one of the main causes of under-nutrition in children < five years of age (1). Chronic malnutrition and stunting in children is thought to carry further life-long morbidity by leading to cognitive and physical deficits with subsequent adverse implications for the economic potential of low and middle income countries (2, 3).

Over the past several decades, there have been substantial efforts to reduce the burden of childhood diarrheal disease. These have included the introduction of an improved oral rehydration solution of lowered osmolarity, the adoption of routine zinc supplementation, the encouragement of exclusive breastfeeding, the introduction of enteropathogen vaccines (e.g. rotavirus) and, critically, public health campaigns to promote these effective therapeutic and preventive approaches (4). Together, these steps have helped to dramatically reduce childhood deaths due to diarrhea from > 5 million in the 1980s (5) to < 1 million recently (6).

Despite these impressive improvements in prevention and therapy for childhood diarrhea, however, there has generally not been a concomitant reduction in rates of childhood undernutrition in young infants and children in resource-poor countries (3, 7–9). Although better treatment and prevention of clinically apparent gastrointestinal infections has been a laudable achievement, these public health efforts have not always resulted in better growth outcomes. Indeed, one modeling approach showed that the near universal provision of many known interventions to prevent childhood growth faltering (including vitamin A and zinc supplementation, balanced energy protein supplementation, complementary feeding, breastfeeding promotion, and prenatal micronutrient supplementation) would only reduce the global prevalence of stunting at 36 months by about a third (4). These and other data have led to the hypothesis that the driver of poor growth may not be clinically apparent infections per se, but instead a chronic, indolent inflammatory state affecting the gastrointestinal tract of children and infants in poor countries (10).

Termed environmental enteric dysfunction (EED), this entity is now hypothesized to be more important for nutritional and other cognitive outcomes compared to clinically apparent infections. Given the large postulated burden of EED in children globally, the paradigm shift from acute infections to EED is a key topic of interest and relevance to the pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition community. There is a current lack in our knowledge regarding the role of nutrition in the development of EED and as a potential intervention. This review provides an overview of the currently proposed underlying causes of EED with specific emphasis on potential interventions.

Environmental Enteric Dysfunction: Definition, Epidemiology & Pathogenesis

Environmental enteric dysfunction (EED) is an acquired subclinical condition of the small intestine among residents of low-income countries that is thought to be a result of chronic exposure to enteropathogens with resultant mucosal inflammation, villous blunting, altered barrier integrity, and reduced intestinal absorptive capacity (10–13). EED has also been variously described in the literature as tropical or environmental enteropathy, subclinical malabsorption, and tropical sprue (13, 14). The term EED has been recently proposed (11) in order to emphasize the functional nature of the lesion, as opposed to basing its definition solely on histopathologic criteria. First described in the 1960–70’s (15–17) studies in Asia, Africa, the Indian sub-continent and Central America showed morphological changes or functional signs of EED in a high proportion of apparently healthy adults and children (18–21). These included clinical or subclinical malabsorption of macro- and micronutrients, as well as increased permeability to small molecules. While widely reported in the 1970–80’s, minimal progress was made on the underlying disease mechanisms, and the topic of EED sharply diminished from the global health literature over the next 20 to 30 years. Interest in the condition has now resurfaced in the context of failure of nutritional interventions, susceptibility to infection with pathogens and poor response to oral vaccines (22), as well as the demonstration that measures of small intestine permeability are related to altered weight and height gain patterns (23).

EED is proposed to be a consequence of the continuous burden of immune-stimulation by fecal-oral exposure to entero-pathogens leading to a persistent acute phase response and chronic inflammation (24, 25). While studies of intestinal biopsies are few and among small numbers of children, EED can be characterized by a spectrum of histological findings ranging from normal to pathologic with a significant reduction in the villus-to-crypt ratio due to villus shortening, crypt hyperplasia and resultant decrease in the surface area of mature absorptive intestinal epithelial cells. Epithelial damage and loss of brush-border enzymes leads to macro- and micronutrient malabsorption (24, 26) (Figure 1). Histological examination can also be notable for lymphocytic and plasma cell infiltration in the lamina propria (12, 13) (Figure 2). Brown et al. recently reported the first animal model of EED (27) and demonstrated that early-life consumption of a 7% protein and 5% fat diet (versus an isocaloric control diet), in combination with iterative oral exposure to commensal Bacteroidales species and Escherichia coli, remodels the murine small intestine to resemble features of EED observed in humans. A critical functional characteristic of EED is altered small intestinal permeability leading to a measurable increase in flux of small water soluble molecules across epithelial cells. The lactulose:mannitol test (described below) has been widely used as a surrogate for the gold standard for diagnosis, especially when biopsies are difficult to obtain (28, 29). Recurrent viral, bacterial, protozoal and/or helminthic infections lead to chronic mucosal inflammation and increased permeability – this both leads to and is a consequence of malnutrition. Parallels can be drawn between EED and other conditions marked by gastrointestinal malabsorption such as celiac disease, Crohn’s disease and intestinal failure syndromes, with the thought that potential diagnostic and therapeutic applications exist from these common clinical pediatric gastroenterology conditions (11, 30–33) (Table 1).

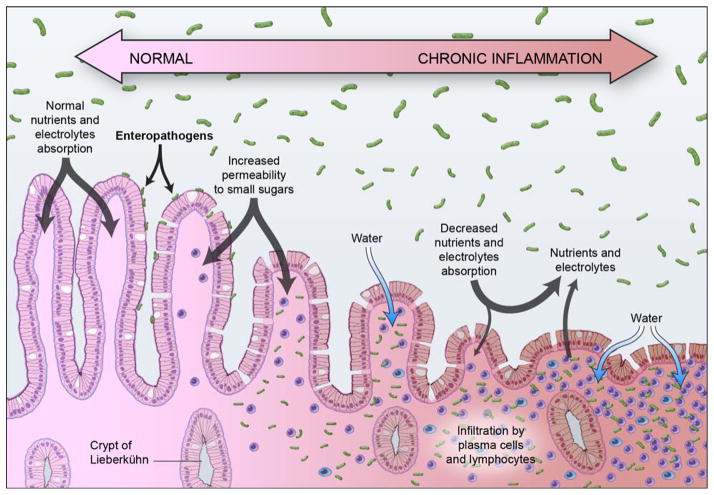

Figure 1.

Proposed schematic progression of Environmental Enteric Dysfunction resulting from a hyper-stimulated enteric immune system: i) chronic recurrent exposure to abnormally high concentrations of ingested enteropathogens in the small-intestinal lumen, ii) mucosal inflammation with infiltration of the lamina propria by plasma cells and lymphocytes, iii) spectrum of villous blunting, altered barrier integrity, and reduced intestinal absorptive capacity (e.g. malabsorption of small sugars such as lactulose). The bidirectional arrow points out the fact that the lesion may improve or worsen over time (Illustration © 2015 Haderer & Muller Biomedical Art).

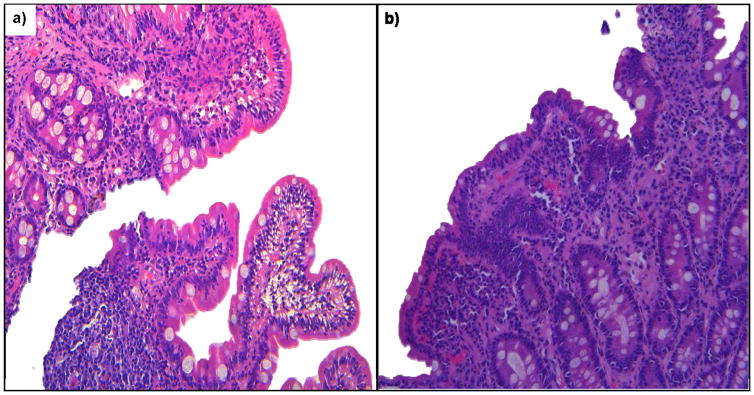

Figure 2.

a) & b) Duodenal biopsies typical histo-pathological features of Environmental Enteric Dysfunction (villus atrophy, crypt hyperplasia and lamina propria infiltration by inflammatory cells) (Histopathology images courtesy of Dr. A Ali)

Table 1.

Summary of known features of Environmental Enteric Dysfunction (EED) and other intestinal malabsorptive conditions

| Disease | Environmental Enteric Dysfunction | Tropical sprue | Celiac disease | Crohn’s disease | Intestinal failure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Sub-clinical enteric dysfunction in residents of low-income countries due to chronic exposure to enteropathogens | Enteric inflammatory disease found in the tropics which may be a more severe form of EED | Small bowel gluten hypersensitive to gluten, leading to difficulty in digesting food | Chronic inflammatory disease which can involve any part of the enteric system, associated with ulcers and fistulae. | Condition characterized by the reduction of functional intestinal mass necessary for adequate digestion and absorption of nutrient, fluid, and growth requirements |

| Signs and Symptoms | Mild to moderate malabsorption with associated stunting/growth failure. Possible diarrhea | Persistent diarrhea, acute weight loss, micronutrient deficiencies | Stool irregularity, abdominal pain, micronutrient (iron, folate) deficiency, FTT, decreased bone mineralization, transaminitis, stunting. Atypical disease: amernorrhea, chronic fatigue, dental enamel defects, dermatitis herpetiformis | Intestinal fistulas/abscesses/strictures, perianal disease, growth failure, bloody diarrhea, extra-intestinal manifestation (arthritis, PSC, psoriasis, uveitis) | Intolerance of enteral nutrition with diarrhea, bloating, emesis, weakness, fatigue |

| Pathogenesis | Persistent acute and chronic inflammation due to a continuous burden of immunostimulation by fecal-oral exposure to enteropathogens | Infections (parasitic, protozoal, bacterial) | Genetic susceptibility: HLA genes encoding the DQ2 & DQ8 molecules, initiated by exposure to gluten proteins. Enteric damage due to combined t-cell and antibody mediated response. | Total of 163 host susceptibility loci meet genome-wide significance thresholds e.g. genes NOD2, ATG161L | Depending on type: short bowel syndrome (due to acquired or congenital disorders of the gastrointestinal tract), intestinal motility disorders (preservation of intestinal length with limited function), and intestinal epithelial defects (e.g. tufting enteropathy, microvillus inclusion disorder) |

| Histopathology | Blunting of intestinal villi, increased crypt lengthening, intraepithelial lymphocytes and lymphocytic infiltration of the lamina propria; can be normal | Intestinal villi blunting, crypt lengthening, intraepithelial lymphocytic infiltration | Similar to EED: Blunting of intestinal villi, increased crypt lengthening, intraepithelial lymphocytes and lymphocytic infiltration of the lamina propria | Chronic inflammation with architectural distortion, granulomas are diagnostic but are not always present | Variable depending on type |

| Serologic Diagnosis/Functional Biomarkers | ¥ Lactose/mannitol test, serum citrulline, fecal calprotectin, plasma cytokines, fecal neopterin, plasma LPS core Ab, LPS binding protein, flagellin specific Ab, soluble CD14, myeloperoxidase, alpha-anti-trypsin, REG1A&B | No established biochemical parameters for diagnosis | Anti-tissue transglutaminase Ig A; anti- endomysial Ig A | No validated diagnostic biomarkers | ¥ serum citrulline, |

Note: Abbreviations – FTT, failure to thrive; HLA, Human Leucocyte Antigen; Ab, antibody; NOD, Nucleotide-binding Oligomerization Domain-containing protein; ATG, autophagy; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; REG1B, stool regenerating gene 1β protein

biomarkers under investigation, evaluating intestinal absorption & mucosal permeability, enterocyte function, inflammation, microbial translocation & immune activation.

Biomarkers of gut function

Although the gold standard for diagnosing the histologic features of EED is via intestinal biopsy, the fact that functional measures of GI absorption and permeability characterize the entity mean that these functional assays have also been proposed as diagnostic tests. It is important to recognize that the ability to obtain small bowel mucosal biopsies from living patients has been a relatively recent addition to the pediatric gastroenterology diagnostic armamentarium (34). We need to be able to safely and cheaply diagnose children with EED, to monitor the effect of interventions and possibly to also screen those at risk. At present, there is no single biomarker/or set of measures that comprehensively and reliably detects early functional bowel dysfunction and the effect on growth faltering (Table 1). Putative biomarkers of EED broadly fall under the following categories:

1. Intestinal absorption and mucosal permeability

For many years, dual sugar permeability tests have stood as the most widely used biomarker of EED. The tests utilize sugars that are not enzymatically digested in the gut and are excreted intact by the kidneys. The lactulose:mannitol (L:M) diagnostic test has been used to assess intestinal barrier function over several decades in multiple populations (35–37). In this test, in patients with normal enteric function, there should be a low level of disaccharide lactulose (larger sugar) compared with monosaccharide mannitol (smaller molecule) in the urine. In patients with impaired intestinal integrity, intestinal permeability to larger sugars increases and that to smaller molecules stays the same or decreases, resulting in higher lactulose to mannitol ratio (38). The L:M test has been investigated in the context of infant malnutrition by Manary et al. (39). While the premise of the test, since it measures true physiology, appear promising, there have been several issues identified with the application of this and other sugar permeability tests to quantify EED. Constraints include variability in the testing reporting, protocol (dosage of sugars given, the solution osmolarity, and the urine collection time) and instrumental performance, all of which combine to limit comparison across different studies. Furthermore, whether high-performance liquid chromatography platforms were used versus enzyme-based assays, study report of excretion ratios versus concentration ratios and the lack of international reference or measurement standards are all factors precluding these from being the ideal test to use in EED.

Increased intestinal permeability leading to protein losses can be measured by fecal α1-anti-trypsin (α 1AT) content. α 1AT is an endogenous glycoprotein present in normal serum at a concentration of 1.9 to 5.0 g/L. It is normally not present in the diet and has a molecular weight similar to albumin. This protease inhibitor is normally not actively secreted, absorbed, and is resistant to degradation by gut proteases (40). α 1AT has been recently used along with neopterin and myeloperoxidase to compose an EE disease activity score as part of the MAL-ED study (see below) (41). Issues with α 1AT as a screening test for EED include its non-specific nature given that elevations can be secondary to common GI infections (eg., Shigella and other invasive species) as well as cardiac or gastrointestinal disorders.

2. Enterocyte mass and function

Measures of enterocyte mass and function are another proposed class of biomarkers and include plasma citrulline (CIT) concentration or measuring increases in CIT after an oral dose of a precursor, alanine-glutamine dipeptide (11, 42). CIT is a non-essential amino acid that is synthesized from glutamine and proline by the enterocytes of the small intestine. Chronic and acute reduction of enterocyte mass has correlated with low plasma CIT and has been validated for quantitative enterocyte mass assessment in villous atrophy disease (43), Crohn’s disease (44), gastrointestinal toxicity of chemotherapy and radiotherapy (45), and for follow-up on small bowel transplantation (46). Recent data from young Malian children with moderate acute malnutrition, showed that CIT increased with gains in WHZ and MUAC during nutritional rehabilitation and could be reflective of improved enteral absorptive ability (47). However, in the setting of systemic inflammation such as sepsis, the entercocytes may be acutely dysfunctional with decreased synthetic ability to make CIT. This would mean that the lab value would not accurately reflect enterocyte mass. Additionally, the kidneys convert CIT into arginine and therefore in the setting of renal impairment, CIT levels may be elevated leading to a false conclusion of elevated enterocyte mass (48).

3. Inflammation

Given that EED is characterized by intestinal inflammation, measures used in clinical diseases characterized by inflammation such as IBD, have been proposed. These include plasma cytokines, stool calprotectin, myeloperoxidase, neopterin and lactoferrin. Cytokines are polypeptides that are 8–30 kDa in size and include interleukins, chemokines, interferons, tumor necrosis factors (TNFs), and growth factors (49) and have been demonstrated to be critical in the modulation of host responses to infection, injury and inflammation. Cytokine analysis can identify the presence of an activated immune response and immunosuppression. It can guide targeted therapeutic regimens designed to reduce inflammation and its secondary effects, or to address a poorly functioning immune system (50). Pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1β, IL-15, IL-17, TNF-α, IFN-γ, GM-CSF) and anti-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-4, IL-6, IL-10) have been studied in many chronic disease states (e.g. IBD, rheumatoid arthritis and dermatitis). Petri et al. recently reported associations of pro-inflammatory cytokines with neurodevelopment in a prospective cohort of Bangladeshi infants from birth until 24 months of age. They showed elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β (> 7.06 pg/mL) and IL-6 (> 10.52 pg/mL) were significantly associated with decreases in motor score, conversely, an elevated level of the Th-2 cytokine IL-4 (> 0.70 pg/mL) was associated with a 3.6 increase in cognitive score (51). Limitations include lack of standardization and use in different clinical settings. Fecal calprotectin has been extensively studied as a non-invasive marker of intestinal inflammation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (52).

Calprotectin is secreted extracellularly from stimulated neutrophils and monocytes, or is released by cell disruption or death (53). However, fecal calprotectin was demonstrated in healthy US children to be elevated in the stools of breastfed children in comparison to infants who were mixed-fed (54). Furthermore, the usefulness of this biomarker remains debated in neonates due to high levels in this age range, more than 5 times higher than in adults and children > 4 years of age, and because of high inter-individual variations in both healthy full-term and preterm infants during the first weeks of life (53).

Myeloperoxidase is a specific leukocytic enzyme that has been used previously to quantify the number of neutrophils in tissue (55). Its activity has been related linearly to the number of neutrophils present. Since leukocytes play an important role in initiating and amplifying the immune response that results in the mucosal damage that is characteristic of inflammatory bowel disease, MPO which is a constituent of neutrophilic granules is an indicator of activity (26). Various prior studies have shown that solubilized MPO from inflamed tissue is directly proportional to the number of neutrophils present (56, 57). MPO levels in patients with IBD are significantly high and a rapid decline is seen with resolution of disease exacerbation. MPO is currently under investigation in ongoing EED studies. Limitations include lack of standardization for MPO assessment and that increased MPO is nonspecific and can reflect activation of neutrophils and macrophages in any infectious, inflammatory, or infiltrative process.

Lactoferrin is an iron-binding glycoprotein found to be concentrated in secondary granules of leukocytes. It is not detected in normal stool specimens unless neutrophils are present and hence is considered to be a useful marker for fecal leukocytes and a measure of intestinal inflammation (58). It has been shown to be elevated in colitis secondary to severe Clostridium difficile (59), cryptosporidiosis (60) and shigellosis (58). Lactoferrin test is rapid, cheap and commercially available. It is limited by need for further investigation into optimum thresholds for the lactoferrin test in different epidemiologic settings such as in areas where diarrheal disease is endemic.

4. Microbial translocation and immune activation

A central component to EED pathogenesis includes microbial translocation and immune activation. Biomarkers measuring this include fecal neopterin, plasma lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–specific and flagellin (FLA)–specific antibodies, and circulating soluble CD14. Neopterin is a catabolic product of guanosine triphosphate and is synthesized by macrophages upon stimulation with the cytokine interferon-gamma serving as a marker of cellular immune system activation as well (61). Investigators following Gambian children with enteropathy for growth outcomes showed that fecal neopterin concentrations were inversely associated with height and weight gain (28). Limitations of neopterin include its nonspecific nature as a marker of activated cell mediated immunity involving release of interferon gamma. Longitudinal serial measurements in the same individual could overcome difficulties with interpretation in settings where chronic parasitic (malaria) or bacterial (tuberculosis) infections may elevate the baseline neopterin level.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)–specific and flagellin (Fla)–specific antibodies have been described as indirect measures of increased gastrointestinal permeability and have been studied in adult IF patients (62): in 23 adults with IF, Fla-specific serum IgM, IgA, and IgG levels were markedly increased compared with controls. LPS-specific IgA was significantly higher in IF patients compared with healthy controls; LPS-specific IgM, IgA, and IgG levels each decreased over time in association with PN weaning. Both LPS– and Fla– antibodies have been studied as biomarkers of systemic infections (63) however, whether this gut barrier dysfunction is associated with growth has not been determined. Preliminary results investigating the relationship of poor growth in young Tanzanian children at risk of EED showed an increase in serum Fla and LPS immunoglobulin (Ig) levels in Tanzanian infants was noted in follow-up versus healthy Boston infants (47). After adjusting for gender, baseline LAZ, and multiple demographic variables, there was a trend toward an increased risk of stunting associated with increased anti-Fla IgG concentrations (HR for Q4 vs. Q1 = 1.52; p for trend = 0.08). Increased anti- Fla IgA, anti-LPS IgA, anti- Fla IgG, and anti-LPS IgG concentrations at 6 wks of age were each associated with an increased risk of subsequent underweight. Limitations of anti-Fla and LPS antibodies include lack of standardization and expense of assays.

5. Intestinal injury and repair

The stool regenerating gene 1β (REG1B) protein has been proposed as a potential measure of intestinal injury and repair. In mouse models, REG1 proteins have been demonstrated to be involved with cellular proliferation and differentiation within the gastrointestinal tract (64). Human Reg1A and Reg1B proteins are both dramatically increased during inflammatory diarrheal diseases. Up-regulated expression of Reg1A and Reg1B genes has also been observed in other gastrointestinal inflammatory disorders including inflammatory bowel disease (65) as well as in colorectal cancer (66). In terms of a role in infectious diseases, it has been found that Reg1A and Reg1B are the most up-regulated genes in colon biopsy samples of individuals with acute E. histolytica colitis (67). Reg1A protein is found in Paneth cells and nonmature columnar cells of small intestinal crypt (68), and the mid-to basal portion of colonic crypts (69), which are areas of epithelial cell renewal. The proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects of Reg1 proteins, the response of these proteins to inflammatory stimuli, and the up-regulation of Reg1A and Reg1B during a broad range of intestinal inflammatory conditions, suggest an important role for these proteins during enteric infections and intestinal inflammation. Limitations similar to other biomarkers under investigation include lack of standardization.

Interventions to improve EED

Multiple postulated mechanisms for impaired growth in children with EED include: (1) decreased nutrient intake; (2) altered nutrient absorption; (3) increased intestinal permeability with subsequent bacterial translocation and immune stimulation; (4) increased energy expenditure due to chronic inflammation; and (5) the growth-inhibiting effects of chronic inflammation (e.g., inhibition of IGF-1 by IL-6) (13, 70). Strategies currently under study to treat EED aim to target several of these. Both nutritional (vitamin A (19), zinc (71), glutamine (72–74), multiple micronutrients (75) and medical (antibiotics (29), anti-inflammatory agents (76), probiotics (18)) therapies have been studied for the treatment of EED (Table 2) (70). Other therapies proposed for future study include drugs which are currently being used or under investigation in diseases with similar pathogenesis such celiac and IBD. In celiac disease, research has been focused on identifying drugs targeted to tight junction regulation. Recently, Larazotide acetate has been shown to decrease intestinal permeability following gluten challenge in celiac disease patients (77). In Crohn’s disease (78) and ulcerative colitis (79), drugs used for epithelial healing include topical 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA/mesalamine) and its derivatives 5-ASA compounds (e.g. sulfasalazine) (80) and topical corticosteroids (e.g. budesonide) (81). Another anti-inflammatory agent currently under investigation for Crohn’s disease to consider for EED would be Mongersen (82), an oral SMAD7 antisense oligonucleotide formulated to deliver its active ingredient primarily into the lumen of the terminal ileum and right colon (82).

Table 2.

Summary of medical & nutritional interventions in children experiencing growth faltering with Environmental Enteric Dysfunction

| Effect on intestinal Permeability | |

|---|---|

| Nutritional Interventions | |

|

| |

| Vitamin A (1, 2) | Decreased |

| Zinc (1) | Decreased |

| Glutamine(3–5) | Variable results depending on study |

| Glycine (3) | Increased |

| Multiple micronutrients (6) | Decreased |

|

| |

| Medical Interventions | |

|

| |

| Mesalazine (5-ASA compound) (7) | Safety study, no evidence of deterioration in intestinal Barrier integrity |

| Probiotics (Lactobacillus CG) (8) | No significant difference |

| Rifaximin (9) | No significant difference |

Research Directions

The Interactions of Malnutrition & Enteric Infections: Consequences for Child Health and Development (MAL-ED)

Increased understanding of the complex inter-relationship between enteric infections and malnutrition is needed to design better intervention strategies to reduce childhood morbidity and mortality. An international investigator group is collaborating on a project entitled The Interactions of Malnutrition & Enteric Infections: Consequences for Child Health and Development (MAL-ED) (83). This project has established a network of sites that focuses on studying populations with a high prevalence of malnutrition and enteric infections. The investigators at the following eight sites, including those in Peru, Brazil, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Tanzania, South Africa and Nepal, and their colleagues in the United States are conducting comprehensive studies, using shared and harmonized protocols, to identify and characterize the factors associated with a child’s risk of enteric infection, chronic diarrhea, malnutrition as well with impaired gut function, vaccine response and cognitive and physical development. These studies will elucidate some of the complex relationships among these factors, leading to more targeted, cost-effective interventions that will further reduce the burden of disease for those living in poverty. The results of these studies are intended to address the following scientific hypotheses, namely that:

Infection with specific enteropathogens leads to malnutrition by causing intestinal inflammation and/or by altering the barrier and adsorptive functions of the gut.

The combination of enteric infections and malnutrition results in growth and cognitive impairments in young children and may lead to impaired immunity as measured by responses to childhood vaccine.

Investigators have quantified the association between intestinal inflammation and linear growth failure using an EE disease activity score comprised of three fecal markers (neopterin, AIATand myeloperoxidase) in children under longitudinal surveillance for diarrheal illness in eight countries. Results were notable for children with the highest score growing 1.08 cm less than children with the lowest score over the 6-month period following the tests after controlling for the incidence of diarrheal disease (41). Recent MAL-ED results published from Bangladesh (84) investigating the relationship between exposure to enteric pathogens through geophagy, consumption of soil, EE, and stunting showed that children with caregiver-reported geophagy had significantly higher EE scores (0.72 point difference, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.01, 1.42) and calprotectin concentrations (237.38 μg/g, 95% CI: 12.77, 462.00). At the 9-month follow-up the odds of being stunted (height-for-age z-score < −2) was double for children with caregiver-reported geophagy (odds ratio [OR]: 2.27, 95% CI: 1.14, 4.51).

The MAL-ED sites also recently reported pathogen-specific burdens of community diarrhea from all their sites (85). Norovirus GII, rotavirus, Campylobacter spp, astrovirus, and Cryptosporidium spp exhibited the highest attributable burdens of diarrhea in the first year of life. The major pathogens associated with diarrhea in the second year of life were Campylobacter spp, norovirus GII, rotavirus, astrovirus, and Shigella spp. Rotavirus had the highest adjusted attributable fraction (AF) for sites without rotavirus vaccination and the fifth highest AF for sites with the vaccination. Bloody diarrhoea was primarily associated with Campylobacter spp and Shigella spp, fever and vomiting with rotavirus, and vomiting with norovirus GII. These findings suggested that although single-pathogen strategies have an important role in the reduction of the burden of severe diarrheal disease, the effect of such interventions on total diarrheal incidence at the community level might be limited. Further results of the MAL-ED study are anticipated to shed critical light on the problem of EED

Microbiome and Vaccine Responsiveness

With increases in our knowledge of the human microbiome and its interplay with the genome (86), the role of a ‘dysbiotic microbiome’ in children with EED is an area of current research (87–90). It has been demonstrated that the human gut microbiome undergoes development over the first 2–3 years of life that is altered in malnourished children, despite receiving high-nutrient interventions (88–90). This is reflective of the critical importance of the first 1000 days of life in the development of stunting (3, 91). A complex interplay involving maternal malnutrition, micronutrient deficiencies in breast milk and complementary foods and/or unhygienic preparation predisposes infants in these resource-poor countries to develop a ‘dysbiotic microbiome’. Researchers from the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh have published results from 48 infants demonstrating that Bifidobacterium predominance early in infancy may enhance thymic development and responses to both oral and parenteral vaccines, whereas deviation resulting in greater bacterial diversity may cause systemic inflammation with lower vaccine responses (92). The authors concluded that vaccine responsiveness may be improved by promoting intestinal bifidobacteria and minimizing dysbiosis early in infancy. There are many questions as yet unanswered regarding the role of the microbiome and the development of EED: 1) Are there possible therapeutic targets (such as use of probiotics or antimicrobials) for intestinal dysbiosis? 2) What is the longitudinal bacterial profile of children at risk of stunting? 3) What is the ‘best microbiome’ to have? 4) Are the microbiomes in otherwise non-diseased non-stunted children living in low and middle-income countries similar to healthy children living in industrialized countries?

However, there needs to be caution when considering which strategies, including the use of antibiotics, to use to help manipulate the microbiome. Blaser et al recently reported (93) that the disruption of the intestinal microbiota during maturation by low-dose antibiotic exposure can alter host metabolism and adiposity. They showed that low-dose penicillin (LDP), delivered from birth, induces metabolic alterations and affects ileal expression of genes involved in immunity. LDP that is limited to early life transiently perturbs the microbiota, which is sufficient to induce sustained effects on body composition, indicating that microbiota interactions in infancy may be critical determinants of long-term host metabolic effects. In addition, LDP enhances the effect of high-fat diet induced obesity. They further highlighted the role of the microbiome by demonstrating that the growth promotion phenotype was transferrable to germ-free hosts by LDP-selected microbiota, showing that the altered microbiome, and not antibiotics, plays a causal role. Oral Rotavirus and Polio vaccine response in children with EED is an area of active research. The Performance of Rotavirus and Oral Polio Vaccines in Developing Countries (PROVIDE) study (94, 95) has been constructed to investigate the association of EED and other possible explanatory factors with oral polio and rotavirus vaccine failure in communities in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and Kolkata, India. Results of the PROVIDE study are pending at the time of this publication.

WAter, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH)

Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) have traditionally been linked to acute gastrointestinal infections. Recently it has been hypothesized that an important pathway through which inadequate WASH access impacts on the burden of disease is via chronic inflammation in EED (96, 97). Improving WASH, as well as the child’s macro- and micronutrient intake, may be the primary means of preventing or mitigating environmental enteropathy and undernutrition. There are commonalities between the WASH and nutrition sectors with regard to research, advocacy and programmatic integration to tackle undernutrition. It is argued that WASH and nutrition as cornerstones of public health share a number of common goals but also common challenges that put both fields at risk of being de-prioritized in health policy (98). However, new evidence has raised questions about the WASH strategy of increased latrine coverage as an effective method for reducing exposure to faecal pathogens and preventing disease. Clasen et al. performed a cluster-randomized trial in India that found that increased toilet coverage did not lead to any significant improvements in the occurrence of child diarrhea, prevalence of parasitic worm infections, child stunting or child mortality (99). The authors highlighted the need for sanitation approaches that meet international coverage targets, but are locally implemented in a way that achieves uptake, reduces exposure, and delivers genuine health gains (99). Further WASH sanitation intervention studies are currently on-going in rural Zimbabwe and Mozambique (100, 101).

Conclusions

There is now enough evidence to suggest an association between recurrent clinical or sub-clinical enteric infections leading to a continuum of changes in the small bowel of children in developing countries, who are exposed to poor sanitation and inadequate environmental hygiene. This gut dysfunction, termed as EED, may lead to poor nutrient absorption, weaker immune response to oral vaccines, stunted growth, and impaired cognitive development. EED is thought to be an acquired condition which potentially may be reversible and has now become the new focus of preventive malnutrition related efforts in the global health context. Studies designed specifically to assess the impact of EED in children using the gold standard of histology from gut biopsies as a primary end-point and growth as a secondary end-point are currently in progress. To date, a limited number of trials have focused on the effect of nutritional and medical interventions on small intestinal permeability (using sugar permeability tests as EED biomarkers). Chronic enteropathies seen in clinical pediatric gastroenterology such as celiac disease, Crohn’s disease and intestinal failure syndromes, can help provide information that can be used to understand EED better. Large multi-country observational studies of infants in low-income countries are currently underway which will help improve our understanding of the pathophysiology of EED along with bringing consensus to an operational definition. Future areas of research focus will include trials exploring therapeutics along with investigation of biomarkers for gut function as a proxy for the gold standard of histology from gut biopsies and the EED microbiome. Exciting opportunities exist for the application of our current clinical understanding of similar entities such as celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease and intestinal failure.

Acknowledgments

SOURCES OF SUPPORT:

SS: None

AA: Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1066200)

CD: NICHD (K24 DK104676), Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (OPP1066203)

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: All authors (SS, AA & CD) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

ETHICAL ADHERENCE: The material in this article represents a review of prior published literature and this study does not involve human subjects, medical records or human tissues.

STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP: All material in this article represents the authors’ own work. Author Contributions:

Syed:

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; and the acquisition, analysis AND Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND Final approval of the version to be published; AND Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ali:

Interpretation of data for the work; AND Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; AND Final approval of the version to be published; AND Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions elated to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Duggan:

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; AND revising the work critically for important intellectual content; AND Final approval of the version to be published; AND Agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

DISCLOSURE OF FUNDING: As above

References

- 1.WHO. Diarrhoeal disease. 2013 [08/24/2015]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs330/en/

- 2.Adair LS, Fall CH, Osmond C, Stein AD, Martorell R, Ramirez-Zea M, et al. Associations of linear growth and relative weight gain during early life with adult health and human capital in countries of low and middle income: findings from five birth cohort studies. Lancet. 2013;382(9891):525–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60103-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Victora CG, de Onis M, Hallal PC, Blossner M, Shrimpton R. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: revisiting implications for interventions. Pediatrics. 2010;125(3):e473–80. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, Cousens S, Dewey K, Giugliani E, et al. What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet. 2008;371(9610):417–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Snyder JD, Merson MH. The magnitude of the global problem of acute diarrhoeal disease: a review of active surveillance data. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1982;60(4):605–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, Perin J, Scott S, Lawn JE, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet. 2012;379(9832):2151–61. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60560-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevens GA, Finucane MM, Paciorek CJ, Flaxman SR, White RA, Donner AJ, et al. Trends in mild, moderate, and severe stunting and underweight, and progress towards MDG 1 in 141 developing countries: a systematic analysis of population representative data. Lancet. 2012;380(9844):824–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60647-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marriott BP, White A, Hadden L, Davies JC, Wallingford JC. World Health Organization (WHO) infant and young child feeding indicators: associations with growth measures in 14 low-income countries. Maternal & child nutrition. 2012;8(3):354–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00380.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krebs NF, Mazariegos M, Chomba E, Sami N, Pasha O, Tshefu A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of meat compared with multimicronutrient-fortified cereal in infants and toddlers with high stunting rates in diverse settings. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(4):840–7. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.041962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humphrey JH. Child undernutrition, tropical enteropathy, toilets, and handwashing. Lancet. 2009;374(9694):1032–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60950-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keusch GT, Denno DM, Black RE, Duggan C, Guerrant RL, Lavery JV, et al. Environmental enteric dysfunction: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and clinical consequences. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(Suppl 4):S207–12. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keusch GT, Rosenberg IH, Denno DM, Duggan C, Guerrant RL, Lavery JV, et al. Implications of acquired environmental enteric dysfunction for growth and stunting in infants and children living in low- and middle-income countries. Food Nutr Bull. 2013;34(3):357–64. doi: 10.1177/156482651303400308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korpe PS, Petri WA., Jr Environmental enteropathy: critical implications of a poorly understood condition. Trends Mol Med. 2012;18(6):328–36. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prendergast A, Kelly P. Enteropathies in the developing world: neglected effects on global health. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86(5):756–63. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chacko CJ, Paulson KA, Mathan VI, Baker SJ. The villus architecture of the small intestine in the tropics: a necropsy study. J Pathol. 1969;98(2):146–51. doi: 10.1002/path.1710980209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindenbaum J, Gerson CD, Kent TH. Recovery of small-intestinal structure and function after residence in the tropics. I. Studies in Peace Corps volunteers. Annals of internal medicine. 1971;74(2):218–22. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-74-2-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keusch GT. Subclinical malabsorption in Thailand. I. Intestinal absorption in Thai children. Am J Clin Nutr. 1972;25(10):1062–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/25.10.1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galpin L, Manary MJ, Fleming K, Ou CN, Ashorn P, Shulman RJ. Effect of Lactobacillus GG on intestinal integrity in Malawian children at risk of tropical enteropathy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82(5):1040–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.5.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thurnham DI, Northrop-Clewes CA, McCullough FS, Das BS, Lunn PG. Innate immunity, gut integrity, and vitamin A in Gambian and Indian infants. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2000;182(Suppl 1):S23–8. doi: 10.1086/315912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goto R, Panter-Brick C, Northrop-Clewes CA, Manahdhar R, Tuladhar NR. Poor intestinal permeability in mildly stunted Nepali children: associations with weaning practices and Giardia lamblia infection. The British journal of nutrition. 2002;88(2):141–9. doi: 10.1079/bjnbjn2002599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fagundes Neto U, Martins MC, Lima FL, Patricio FR, Toledo MR. Asymptomatic environmental enteropathy among slum-dwelling infants. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 1994;13(1):51–6. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1994.10718371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qadri F, Bhuiyan TR, Sack DA, Svennerholm AM. Immune responses and protection in children in developing countries induced by oral vaccines. Vaccine. 2013;31(3):452–60. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lunn PG, Northrop-Clewes CA, Downes RM. Intestinal permeability, mucosal injury, and growth faltering in Gambian infants. Lancet. 1991;338(8772):907–10. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91772-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell DI, Elia M, Lunn PG. Growth faltering in rural Gambian infants is associated with impaired small intestinal barrier function, leading to endotoxemia and systemic inflammation. J Nutr. 2003;133(5):1332–8. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solomons NW. Environmental contamination and chronic inflammation influence human growth potential. J Nutr. 2003;133(5):1237. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campbell DI, Murch SH, Elia M, Sullivan PB, Sanyang MS, Jobarteh B, et al. Chronic T cell-mediated enteropathy in rural west African children: relationship with nutritional status and small bowel function. Pediatr Res. 2003;54(3):306–11. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000076666.16021.5E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown EM, Wlodarska M, Willing BP, Vonaesch P, Han J, Reynolds LA, et al. Diet and specific microbial exposure trigger features of environmental enteropathy in a novel murine model. Nature communications. 2015;6:7806. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell DI, McPhail G, Lunn PG, Elia M, Jeffries DJ. Intestinal inflammation measured by fecal neopterin in Gambian children with enteropathy: association with growth failure, Giardia lamblia, and intestinal permeability. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39(2):153–7. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200408000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trehan I, Shulman RJ, Ou CN, Maleta K, Manary MJ. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of rifaximin, a nonabsorbable antibiotic, in the treatment of tropical enteropathy. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2009;104(9):2326–33. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nath SK. Tropical sprue. Current gastroenterology reports. 2005;7(5):343–9. doi: 10.1007/s11894-005-0002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hill ID, Dirks MH, Liptak GS, Colletti RB, Fasano A, Guandalini S, et al. Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of celiac disease in children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40(1):1–19. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200501000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jostins L, Ripke S, Weersma RK, Duerr RH, McGovern DP, Hui KY, et al. Host-microbe interactions have shaped the genetic architecture of inflammatory bowel disease. Nature. 2012;491(7422):119–24. doi: 10.1038/nature11582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krawinkel MB, Scholz D, Busch A, Kohl M, Wessel LM, Zimmer KP. Chronic intestinal failure in children. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2012;109(22–23):409–15. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shiner M. Coeliac disease: histopathological findings in the small intestinal mucosa studies by a peroral biopsy technique. Gut. 1960;1:48–54. doi: 10.1136/gut.1.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bjarnason I, MacPherson A, Hollander D. Intestinal permeability: an overview. Gastroenterology. 1995;108(5):1566–81. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ford RP, Menzies IS, Phillips AD, Walker-Smith JA, Turner MW. Intestinal sugar permeability: relationship to diarrhoeal disease and small bowel morphology. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1985;4(4):568–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nathavitharana KA, Lloyd DR, Raafat F, Brown GA, McNeish AS. Urinary mannitol: lactulose excretion ratios and jejunal mucosal structure. Arch Dis Child. 1988;63(9):1054–9. doi: 10.1136/adc.63.9.1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee GO, Kosek P, Lima AA, Singh R, Yori PP, Olortegui MP, et al. Lactulose: mannitol diagnostic test by HPLC and LC-MSMS platforms: considerations for field studies of intestinal barrier function and environmental enteropathy. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;59(4):544–50. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weisz AJ, Manary MJ, Stephenson K, Agapova S, Manary FG, Thakwalakwa C, et al. Abnormal gut integrity is associated with reduced linear growth in rural Malawian children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2012;55(6):747–50. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3182650a4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crossley JR, Elliott RB. Simple method for diagnosing protein-losing enteropathies. British medical journal. 1977;1(6058):428–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6058.428-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kosek M, Haque R, Lima A, Babji S, Shrestha S, Qureshi S, et al. Fecal markers of intestinal inflammation and permeability associated with the subsequent acquisition of linear growth deficits in infants. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;88(2):390–6. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.12-0549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peters JH, Wierdsma NJ, Teerlink T, van Leeuwen PA, Mulder CJ, van Bodegraven AA. The citrulline generation test: proposal for a new enterocyte function test. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics. 2008;27(12):1300–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crenn P, Vahedi K, Lavergne-Slove A, Cynober L, Matuchansky C, Messing B. Plasma citrulline: A marker of enterocyte mass in villous atrophy-associated small bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(5):1210–9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papadia C, Sherwood RA, Kalantzis C, Wallis K, Volta U, Fiorini E, et al. Plasma citrulline concentration: a reliable marker of small bowel absorptive capacity independent of intestinal inflammation. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2007;102(7):1474–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01239.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gosselin KB, Feldman HA, Sonis AL, Bechard LJ, Kellogg MD, Gura K, et al. Serum citrulline as a biomarker of gastrointestinal function during hematopoietic cell transplantation in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2014;58(6):709–14. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lutgens LC, Deutz N, Granzier-Peeters M, Beets-Tan R, De Ruysscher D, Gueulette J, et al. Plasma citrulline concentration: a surrogate end point for radiation-induced mucosal atrophy of the small bowel. A feasibility study in 23 patients. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2004;60(1):275–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McDonald C, Hao T, Gosselin K, Manji K, Gewirtz A, Kisenge R, et al. Elevations in Serum Anti-flagellin and Anti-lipopolysaccharide Immunoglobulins are related to underweight in young Tamzanian children. The FASEB Journal. 2015;29(no.1 supplement 403.4) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Piton G, Manzon C, Cypriani B, Carbonnel F, Capellier G. Acute intestinal failure in critically ill patients: is plasma citrulline the right marker? Intensive care medicine. 2011;37(6):911–7. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2172-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cannon JG. Inflammatory Cytokines in Nonpathological States. News in physiological sciences : an international journal of physiology produced jointly by the International Union of Physiological Sciences and the American Physiological Society. 2000;15:298–303. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.2000.15.6.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Siebert S, Tsoukas A, Robertson J, McInnes I. Cytokines as therapeutic targets in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory diseases. Pharmacological reviews. 2015;67(2):280–309. doi: 10.1124/pr.114.009639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jiang NM, Tofail F, Moonah SN, Scharf RJ, Taniuchi M, Ma JZ, et al. Febrile illness and pro-inflammatory cytokines are associated with lower neurodevelopmental scores in Bangladeshi infants living in poverty. BMC pediatrics. 2014;14:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mao R, Xiao YL, Gao X, Chen BL, He Y, Yang L, et al. Fecal calprotectin in predicting relapse of inflammatory bowel diseases: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2012;18(10):1894–9. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kapel N, Campeotto F, Kalach N, Baldassare M, Butel MJ, Dupont C. Faecal calprotectin in term and preterm neonates. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;51(5):542–7. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181e2ad72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dorosko SM, Mackenzie T, Connor RI. Fecal calprotectin concentrations are higher in exclusively breastfed infants compared to those who are mixed-fed. Breastfeeding medicine : the official journal of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. 2008;3(2):117–9. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2007.0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Williams JG, Hughes LE, Hallett MB. Toxic oxygen metabolite production by circulating phagocytic cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1990;31(2):187–93. doi: 10.1136/gut.31.2.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krawisz JE, Sharon P, Stenson WF. Quantitative assay for acute intestinal inflammation based on myeloperoxidase activity. Assessment of inflammation in rat and hamster models. Gastroenterology. 1984;87(6):1344–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weissmann G, Smolen JE, Korchak HM. Release of inflammatory mediators from stimulated neutrophils. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(1):27–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007033030109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guerrant RL, Araujo V, Soares E, Kotloff K, Lima AA, Cooper WH, et al. Measurement of fecal lactoferrin as a marker of fecal leukocytes. Journal of clinical microbiology. 1992;30(5):1238–42. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.5.1238-1242.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Steiner TS, Flores CA, Pizarro TT, Guerrant RL. Fecal lactoferrin, interleukin-1beta, and interleukin-8 are elevated in patients with severe Clostridium difficile colitis. Clinical and diagnostic laboratory immunology. 1997;4(6):719–22. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.6.719-722.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alcantara CS, Yang CH, Steiner TS, Barrett LJ, Lima AA, Chappell CL, et al. Interleukin-8, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and lactoferrin in immunocompetent hosts with experimental and Brazilian children with acquired cryptosporidiosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2003;68(3):325–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Murr C, Widner B, Wirleitner B, Fuchs D. Neopterin as a marker for immune system activation. Current drug metabolism. 2002;3(2):175–87. doi: 10.2174/1389200024605082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ziegler TR, Luo M, Estivariz CF, Moore DA, 3rd, Sitaraman SV, Hao L, et al. Detectable serum flagellin and lipopolysaccharide and upregulated anti-flagellin and lipopolysaccharide immunoglobulins in human short bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294(2):R402–10. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00650.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Galloway DP, Troutt ML, Kocoshis SA, Gewirtz AT, Ziegler TR, Cole CR. Increased Anti-Flagellin and Anti-Lipopolysaccharide Immunoglobulins in Pediatric Intestinal Failure: Associations With Fever and Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections. JPEN Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. 2015;39(5):562–8. doi: 10.1177/0148607114537073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Miyaoka Y, Kadowaki Y, Ishihara S, Ose T, Fukuhara H, Kazumori H, et al. Transgenic overexpression of Reg protein caused gastric cell proliferation and differentiation along parietal cell and chief cell lineages. Oncogene. 2004;23(20):3572–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kawanami C, Fukui H, Kinoshita Y, Nakata H, Asahara M, Matsushima Y, et al. Regenerating gene expression in normal gastric mucosa and indomethacin-induced mucosal lesions of the rat. Journal of gastroenterology. 1997;32(1):12–8. doi: 10.1007/BF01213290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Watanabe T, Yonekura H, Terazono K, Yamamoto H, Okamoto H. Complete nucleotide sequence of human reg gene and its expression in normal and tumoral tissues. The reg protein, pancreatic stone protein, and pancreatic thread protein are one and the same product of the gene. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1990;265(13):7432–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Peterson KM, Guo X, Elkahloun AG, Mondal D, Bardhan PK, Sugawara A, et al. The expression of REG 1A and REG 1B is increased during acute amebic colitis. Parasitology international. 2011;60(3):296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dieckgraefe BK, Crimmins DL, Landt V, Houchen C, Anant S, Porche-Sorbet R, et al. Expression of the regenerating gene family in inflammatory bowel disease mucosa: Reg Ialpha upregulation, processing, and antiapoptotic activity. Journal of investigative medicine : the official publication of the American Federation for Clinical Research. 2002;50(6):421–34. doi: 10.1136/jim-50-06-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sekikawa A, Fukui H, Fujii S, Nanakin A, Kanda N, Uenoyama Y, et al. Possible role of REG Ialpha protein in ulcerative colitis and colitic cancer. Gut. 2005;54(10):1437–44. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.053587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Petri WA, Naylor C, Haque R. Environmental enteropathy and malnutrition: do we know enough to intervene? BMC Med. 2014;12(1):187. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen P, Soares AM, Lima AA, Gamble MV, Schorling JB, Conway M, et al. Association of vitamin A and zinc status with altered intestinal permeability: analyses of cohort data from northeastern Brazil. Journal of health, population, and nutrition. 2003;21(4):309–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Williams EA, Elia M, Lunn PG. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, glutamine-supplementation trial in growth-faltering Gambian infants. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;86(2):421–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/86.2.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lima NL, Soares AM, Mota RM, Monteiro HS, Guerrant RL, Lima AA. Wasting and intestinal barrier function in children taking alanyl-glutamine-supplemented enteral formula. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007;44(3):365–74. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31802eecdd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lima AA, Brito LF, Ribeiro HB, Martins MC, Lustosa AP, Rocha EM, et al. Intestinal barrier function and weight gain in malnourished children taking glutamine supplemented enteral formula. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40(1):28–35. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Smith HE, Ryan KN, Stephenson KB, Westcott C, Thakwalakwa C, Maleta K, et al. Multiple micronutrient supplementation transiently ameliorates environmental enteropathy in Malawian children aged 12–35 months in a randomized controlled clinical trial. J Nutr. 2014;144(12):2059–65. doi: 10.3945/jn.114.201673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Jones KD, Hunten-Kirsch B, Laving AM, Munyi CW, Ngari M, Mikusa J, et al. Mesalazine in the initial management of severely acutely malnourished children with environmental enteric dysfunction: a pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2014;12:133. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0133-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Leffler DA, Kelly CP, Green PH, Fedorak RN, DiMarino A, Perrow W, et al. Larazotide acetate for persistent symptoms of celiac disease despite a gluten-free diet: a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(7):1311–9. e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lahad A, Weiss B. Current therapy of pediatric Crohn’s disease. World journal of gastrointestinal pathophysiology. 2015;6(2):33–42. doi: 10.4291/wjgp.v6.i2.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Regan BP, Bousvaros A. Pediatric ulcerative colitis: a practical guide to management. Paediatric drugs. 2014;16(3):189–98. doi: 10.1007/s40272-014-0070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Perrotta C, Pellegrino P, Moroni E, De Palma C, Cervia D, Danelli P, et al. Five-aminosalicylic Acid: an update for the reappraisal of an old drug. Gastroenterology research and practice. 2015;2015:456895. doi: 10.1155/2015/456895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Scott FI, Osterman MT. Medical management of crohn disease. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2013;26(2):67–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1348043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Monteleone G, Neurath MF, Ardizzone S, Di Sabatino A, Fantini MC, Castiglione F, et al. Mongersen, an oral SMAD7 antisense oligonucleotide, and Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(12):1104–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1407250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kosek M, Guerrant RL, Kang G, Bhutta Z, Yori PP, Gratz J, et al. Assessment of environmental enteropathy in the MAL-ED cohort study: theoretical and analytic framework. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(Suppl 4):S239–47. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.George CM, Oldja L, Biswas S, Perin J, Lee GO, Kosek M, et al. Geophagy is associated with environmental enteropathy and stunting in children in rural Bangladesh. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92(6):1117–24. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Platts-Mills JA, Babji S, Bodhidatta L, Gratz J, Haque R, Havt A, et al. Pathogen-specific burdens of community diarrhoea in developing countries: a multisite birth cohort study (MALED) Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(9):e564–75. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00151-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Group NHW, Peterson J, Garges S, Giovanni M, McInnes P, Wang L, et al. The NIH Human Microbiome Project. Genome research. 2009;19(12):2317–23. doi: 10.1101/gr.096651.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gough EK, Stephens DA, Moodie EE, Prendergast AJ, Stoltzfus RJ, Humphrey JH, et al. Linear growth faltering in infants is associated with Acidaminococcus sp. and community-level changes in the gut microbiota. Microbiome. 2015;3:24. doi: 10.1186/s40168-015-0089-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Subramanian S, Huq S, Yatsunenko T, Haque R, Mahfuz M, Alam MA, et al. Persistent gut microbiota immaturity in malnourished Bangladeshi children. Nature. 2014;510(7505):417–21. doi: 10.1038/nature13421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smith MI, Yatsunenko T, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Mkakosya R, Cheng J, et al. Gut microbiomes of Malawian twin pairs discordant for kwashiorkor. Science. 2013;339(6119):548–54. doi: 10.1126/science.1229000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, et al. Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature. 2012;486(7402):222–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Horton R. Maternal and child undernutrition: an urgent opportunity. Lancet. 2008;371(9608):179. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61869-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Huda MN, Lewis Z, Kalanetra KM, Rashid M, Ahmad SM, Raqib R, et al. Stool microbiota and vaccine responses of infants. Pediatrics. 2014;134(2):e362–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cox LM, Yamanishi S, Sohn J, Alekseyenko AV, Leung JM, Cho I, et al. Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell. 2014;158(4):705–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.The PROVIDE Study (Performance of Rotavirus and Oral Polio Vaccines in Developing Countries) 2015 Nov 17; doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0518. Available from: https://www.providestudy.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Kirkpatrick BD, Colgate ER, Mychaleckyj JC, Haque R, Dickson DM, Carmolli MP, et al. The “Performance of Rotavirus and Oral Polio Vaccines in Developing Countries” (PROVIDE) study: description of methods of an interventional study designed to explore complex biologic problems. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;92(4):744–51. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.14-0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Arnold BF, Null C, Luby SP, Unicomb L, Stewart CP, Dewey KG, et al. Cluster-randomised controlled trials of individual and combined water, sanitation, hygiene and nutritional interventions in rural Bangladesh and Kenya: the WASH Benefits study design and rationale. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8):e003476. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bartram J, Cairncross S. Hygiene, sanitation, and water: forgotten foundations of health. PLoS Med. 2010;7(11):e1000367. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Luby S. Is targeting access to sanitation enough? Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(11):E619–E20. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70326-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Clasen T, Boisson S, Routray P, Torondel B, Bell M, Cumming O, et al. Effectiveness of a rural sanitation programme on diarrhoea, soil-transmitted helminth infection, and child malnutrition in Odisha, India: a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(11):e645–53. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70307-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brown J, Cumming O, Bartram J, Cairncross S, Ensink J, Holcomb D, et al. A controlled, before-and-after trial of an urban sanitation intervention to reduce enteric infections in children: research protocol for the Maputo Sanitation (MapSan) study, Mozambique. BMJ Open. 2015;5(6):e008215. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mbuya MN, Tavengwa NV, Stoltzfus RJ, Curtis V, Pelto GH, Ntozini R, et al. Design of an Intervention to Minimize Ingestion of Fecal Microbes by Young Children in Rural Zimbabwe. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(Suppl 7):S703–9. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Peterson KM, Buss J, Easley R, Yang Z, Korpe PS, Niu F, et al. REG1B as a predictor of childhood stunting in Bangladesh and Peru. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(5):1129–33. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.048306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]