Abstract

Objective

To compare rates of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or greater (CIN3+) between women age 21–24 and women ≥ age 25 undergoing a see-and-treat strategy for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) cytology.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, women treated with a see-and-treat loop electrosurgical excisional procedure (LEEP) for HSIL cytology at our university-based colposcopy clinic between 2008–2013 were identified. Data collected included age, race, parity, smoking status, method of contraception, history of abnormal cytology, HIV status, and LEEP histology. Cohorts were compared using Pearson’s Chi-squared test of association and Fischer’s exact test.

Results

369 women were included in this analysis. The mean age was 30 (SD 7.2, range 21–56). 97 women (26.3%) were 21–24 years old. The rate of CIN3 in all women undergoing a see-and-treat LEEP for HSIL cytology was 65.9% (95% CI 60.8–70.5). The rate of CIN 2 was 15.2% (95% CI 11.9–19.2). 3 women (1.1%) had invasive carcinoma. There was no difference in risk of CIN3+ in the young women compared to women ≥25 (RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.92–2.02). Within this see-and-treat population, there was no correlation between presence of CIN3+ and race, smoking, contraception, or HIV status.

Conclusion

The majority of women undergoing see-and-treat for HSIL cytology will have CIN3 on final histology. In this large cohort, women ages 21–24 did not have lower rates of CIN3 compared to women age 25 and older, suggesting that see-and-treat is still a valid treatment option for the prevention of invasive disease in young women.

Keywords: see-and-treat, young women, HSIL, LEEP, colposcopy

Introduction

High-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is a precursor to invasive cervical cancer [1]. In most cervical cancer screening algorithms, women with abnormal cytology are referred for colposcopic-directed biopsy. If CIN 2 or 3 is detected, an excisional procedure such as a loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) or a cold knife cone (CKC) is usually recommended [2]. Secondary to the high prevalence of CIN2+ (defined as CIN2, CIN3, or invasive cancer) in women with high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) on cervical cytology, an alternative strategy, the “see-and-treat” method, was developed in which patients are treated with an immediate excisional procedure without prior colposcopic-guided biopsy [3–5]. Benefits of the see-and-treat method include fewer required visits and lower cost, which may be particularly beneficial for low-income patients in whom lack of transportation, lack of insurance or other financial concerns can be significant barriers to treatment. Risks of see-and-treat include risk of overtreatment and potential risks of future adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preterm birth [3, 6–9].

The 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors released by the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP) recommend against the use of the see-and-treat strategy in women under age 25 [2]. This recommendation is a result of several studies demonstrating low incidence of CIN3+ (defined as CIN3 or invasive cancer), high rates of regression of CIN2 and potential adverse effects of excisional procedures on future pregnancy outcomes in women 25 years of age and under [10–14].

In light of the new guidelines, our study sought to determine whether women age 21–24 had a decreased risk of CIN3+ compared to women greater than 25 after see-and-treat for HSIL.

Materials and Methods

Following approval by the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Institutional Review Board, clinic records from the UAB Colposcopy Clinic were reviewed to identify all patients who underwent a see-and-treat LEEP for HSIL cytology from January 2008 to May 2013. This large, university-based colposcopy clinic serves as a statewide referral center for women who are either uninsured or have Medicaid. This study time period preceded implementation of the National Affordable care act.

The medical record of each subject was reviewed. Abstracted information included age, race, parity, method of contraception, smoking history, previous abnormal cytology or diagnosis of CIN, and history of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Rates of CIN3 were determined by review of the formal histologic reports for each LEEP specimen, which had been interpreted by a gynecologic pathologist at the time of collection. No patients were excluded. Patients were divided into two cohorts in accordance with the 2012 updated consensus guidelines published by the ASCCP - the first consisting of women ages 21–24 (young cohort), and the second consisting of women age 25 or greater (standard cohort) [2].

Patient characteristics and the primary outcome were compared between cohorts using Pearson’s Chi-squared test of association and Fischer’s exact test. Relative risk and 95% confidence intervals were also calculated. A multivariable, mutually adjusted logistic regression was conducted to measure the effect of age group in predicting the primary outcome. A p value of <0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). A post hoc power analysis revealed an 80% power to detect a 14% decrease in risk of CIN3+ in women ages 21–24.

Results

We identified a total of 369 women with HSIL cytology treated with a see-and-treat LEEP in our university colposcopy clinic between January 2008 and May 2013. These women were divided into two cohorts in accordance with the ASCCP Updated Consensus Guidelines. The young cohort included women less than age 25, while the standard cohort included women age 25 and older. The mean age of all eligible patients was 30 (standard deviation 7.2, range 21–56). The mean age in the young cohort was 23 (standard deviation 1.0, range 21–24), and the mean age in the standard cohort was 32 (standard deviation 7.0, range 25–56).

Most women were White (n=189, 51.2%) or Black (n=143, 38.8%). The majority of women were parous (n=292, 79.1%). 189 women (50.4%) were current or former smokers. 276 women (79.4%) used contraception. The most popular contraceptive choices were depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (n=88, 23.8%) and oral contraceptive pills (n=79, 21.4%). 216 women (58.5%) had a history of abnormal cytology or CIN, including 90 patients (24.3%) with previous low-grade cytology or CIN1 and 126 patients (34.1%) with a previous history of CIN2+. 42 patients (11.4%) were missing data on smoking history, current contraceptive method, parity, or previous history of CIN.

There were significant differences between the young and standard cohorts when comparing race and parity. More women were White in the young cohort compared to the standard cohort (62.9% versus 48.3%; p=0.022). Not surprisingly, there were more parous women in the standard cohort than the young cohort (82.0% versus 71.1%; p=0.0003). There were no differences between cohorts when comparing smoking status, history of abnormal cytology or CIN, or presence of HIV (Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of Baseline Characteristics between Young and Standard Cohorts

| Total (N=369) | Age 21–24 (N=97) | Age ≥ 25 (N=272) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| CIN3+* | ||||

| Yes | 246 (66.7) | 71 (73.2) | 175 (64.3) | 0.11 |

| No | 123 (33.3) | 26 (26.8) | 97 (35.7) | |

|

| ||||

| Race | ||||

| White | 189 (51.2) | 61 (62.9) | 128 (47.1) | 0.022 |

| Black | 143 (38.8) | 27 (27.8) | 116 (42.6) | |

| Hispanic | 30 (8.1) | 9 (9.3) | 21 (7.7) | |

| Other/Unknown | 7 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (2.6) | |

|

| ||||

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Nonsmoker | 167 (45.2) | 43 (44.3) | 124 (45.6) | 0.56 |

| Current/Former Smoker | 186 (50.4) | 53 (54.6) | 133 (48.9) | |

| Unknown | 16 (4.3) | 1 (1.0) | 15 (5.5) | |

|

| ||||

| Parity | ||||

| Nulliparous | 58 (15.7) | 23 (25.0) | 35 (13.6) | 0.0003 |

| Para 1 | 109 (29.5) | 37 (40.2) | 72 (27.9) | |

| Multiparous (Para 2+) | 183 (49.6) | 32 (34.8) | 151 (58.5) | |

| Unknown | 19 (5.1) | 5 (5.2) | 14 (5.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Contraception Use | ||||

| Yes | 276 (74.8) | 82 (84.5) | 194 (77.6) | 0.15 |

| No | 71 (19.2) | 15 (15.6) | 56 (22.4) | |

| Unknown | 22 (6.0) | 0 (0.0) | 22 (8.1) | |

|

| ||||

| Previous History of CIN | ||||

| None | 130 (35.2) | 41 (42.3) | 89 (32.7) | 0.24 |

| LSIL**/CIN1 | 90 (24.3) | 19 (19.6) | 71 (26.1) | |

| Untreated HSIL**, CIN2 or 3 | 84 (22.7) | 26 (26.8) | 58 (21.3) | |

| Treated CIN2 or 3 | 42 (11.3) | 9 (9.3) | 33 (12.1) | |

| Unknown | 23 (6.2) | 2 (2.1) | 21 (7.7) | |

|

| ||||

| HIV Positive | ||||

| Yes | 10 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (3.7) | 0.069+ |

| No | 359 (97.3) | 97 (100.0) | 262 (96.3) | |

All data reported as n (%). Unknown variables not included in statistical analysis. LSIL = low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, HSIL = high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, CIN = cervical intraepithelial neoplasia, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus.

CIN3+ includes histologic diagnosis of CIN3 or invasive cancer

Refer to cervical cytology reports

P-value from two-sided Fischer’s Exact Test instead of Pearson’s Chi-square test of association

Of the entire study population, there were 305 women (82.7%) with CIN2+ on final histology after see-and-treat. Specifically, 56 women (15.2%) had CIN2, 246 women (66.7%) had CIN3, and 3 women (1.1%) were found to have invasive cervical cancer (Figure 1). The three women who were diagnosed with invasive cancer were all in the standard cohort (ages 28, 40, and 40) and had no known history of CIN or abnormal cytology. There was no difference in age, race, smoking status, method of contraception, or presence of HIV in women who had CIN3+ compared to those who did not.

Figure 1.

Distribution of histology in all patients undergoing see-and-treat LEEP for HSIL cytology, n=369.

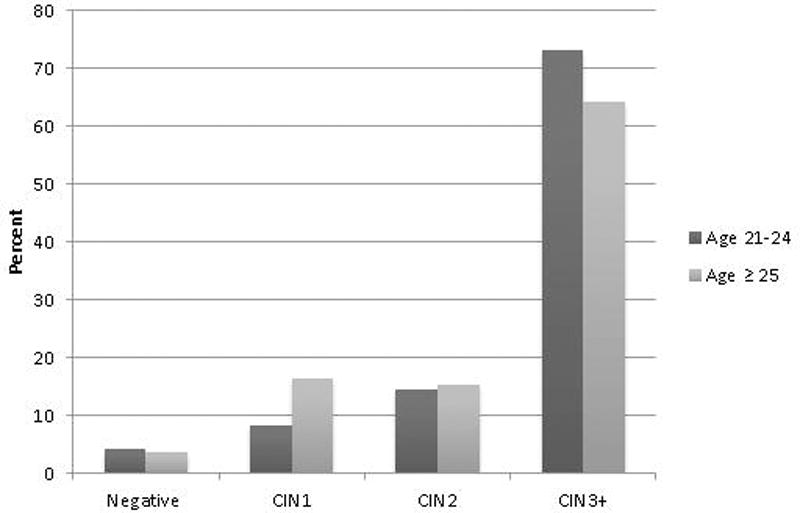

73.2% of women (n=71) in the young women cohort had CIN3+ on final histology compared to 64.3% of women (n=175) in the standard cohort (Figure 2). Women ages 21–24 did not have a lower rate of CIN3+ compared to women age 25 or older (RR 1.37, 95% CI 0.92–2.02).

Figure 2.

LEEP histology in women ages 21–24 compared to women age 25 or older after see-and-treat LEEP for HSIL.

Since the young and standard cohorts differed significantly in race and parity, a logistic regression model was created to predict CIN3+ using age group, race, and parity. The results indicate that only parity was statistically significant in predicting CIN3+ (OR 2.35, 95% CI 1.3–4.2; Table 2).

Table 2.

Results of Multivariable, Mutually Adjusted Logistic Regression Model including Age Group, Race and Parity

| Effect | Point Estimate | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age 21–24 vs age >25 | 1.698 | 0.987 – 2.920 | 0.056 |

| Black Race* | 1.199 | 0.740 – 1.942 | 0.580 |

| Hispanic Race* | 1.052 | 0.456 – 2.426 | 0.922 |

| Multiparity | 2.353 | 1.307 – 4.239 | 0.004 |

Compared to White Race

Discussion

Despite advances in cervical cancer screening, the decline in incidence of cervical cancer has plateaued in recent years [15]. Both worldwide and in the United States, there are significant income-related disparities in the morbidity and mortality from invasive cervical cancer [16]. In the United States, greater than 60% of invasive cervical cancers are diagnosed in underserved populations where poverty, limited education, and poor access to healthcare may limit appropriate screening for and treatment of pre-invasive disease [16].

CIN3 is a known precursor to invasive cancer, and while prospective data are limited, at least a third of women with untreated CIN3 will go on to develop invasive cervical cancer [1]. Our large cohort study demonstrates that the majority of women (66.7%) with HSIL cytology will have CIN3+ on their final histology, and there is no difference in the rate of CIN3+ in women ages 21–24 compared to women age 25 or older. See-and-treat has been the preferred option for treatment of HSIL cytology for women in our colposcopy clinic secondary to high rates of CIN3, poor follow-up rates, and long distances from this central referral clinic. Moreover, our state has both a higher age-adjusted incidence rate of cervical cancer, 8.7 per 100,000 women, as compared to the national average of 8.1 per 100,000 women, in addition to a higher mortality rate from the disease [17]. Under the new ASCCP guidelines, see-and-treat is considered unacceptable for treatment of HSIL in women under age 25 due to potential for adverse pregnancy outcomes and possibility of regression of CIN2 [2].

While many studies have examined pregnancy outcomes after LEEP, the data are conflicting [18]. Conner et al. recently performed a large meta-analysis including 19 studies and over 1.4 million women. Although women with a history of LEEP had an increased risk of preterm delivery compared to women without LEEP (RR 1.61, 95% CI 1.35–1.92), there was no difference in preterm birth rate in women with history of LEEP compared to women with a history of cervical dysplasia but no previous LEEP (RR 1.08, 95% CI 0.88–1.33). The authors concluded that preterm labor and cervical dysplasia have similar risk factors, which likely explain the association between LEEP and preterm delivery [19].

In addition to concerns about future pregnancy outcomes, evidence of high regression rates of CIN2 and low incidence of invasive disease has prompted concerns about overtreatment of CIN in young women. Katki et al. demonstrated that the 5-year risk of invasive disease for women ages 21–24 was essentially zero regardless of cytology results; however, these same women had a 5-year risk of CIN3+ of 28%, equivalent to women ages 25–29 [14]. Importantly, many patients included in this study are from a well-screened population with a lower than average risk of cervical cancer, which is vastly different from our referral population [20].

More conservative algorithms cannot be effective in management of CIN unless patients can be counted on to reliably present for follow up visits. In patients who lack resources such as health insurance and access to transportation, the increased number of visits required for conservative management may pose substantial barriers to treatment. The see-and-treat strategy combines diagnosis and treatment in a single visit, eliminating the need for multiple follow-up visits. In regions with a higher cervical cancer prevalence, such as our own, it is important to capitalize on opportunities to treat pre-invasive disease. We have demonstrated in this study that rates of overtreatment with the see-and-treat approach are low and that even young women have high rates of CIN3+.

We believe that see-and-treat still warrants consideration in management of HSIL cytology, even in women less than 25. Limitations of our study include potential confounding variables that are unaccounted for as well as the known potential biases associated with a retrospective study design. Prospective trials that evaluate this important question in populations with high rates of cervical cancer should be considered.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure of Financial Support: This research was supported in part by a NIH grant to CAL (5K12HD0012580-15).

Abbreviations

- CIN

cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- HSIL

high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

- LEEP

loop electrosurgical excision procedure

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- CI

confidence interval

- CKC

cold knife conization

- ASCCP

American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology

- UAB

University of Alabama at Birmingham

- LSIL

low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Report: Warner K. Huh, M.D. serves as a member of the Merck Scientific Advisory Board. None of the other authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

IRB Status: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Alabama at Birmingham

Previous Presentation: Poster presentation at Society for Gynecologic Oncology’s 45th Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer, March 22–25, 2014, Tampa, Florida

References

- 1.McCredie MR, et al. Natural history of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9(5):425–34. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massad LS, et al. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(5 Suppl 1):S1–S27. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e318287d329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn TS, Burke M, Shwayder J. A “see and treat” management for high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion pap smears. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2003;7(2):104–6. doi: 10.1097/00128360-200304000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massad LS, Collins YC, Meyer PM. Biopsy correlates of abnormal cervical cytology classified using the Bethesda system. Gynecol Oncol. 2001;82(3):516–22. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2001.6323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Numnum TM, et al. A prospective evaluation of “see and treat” in women with HSIL Pap smear results: is this an appropriate strategy? J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2005;9(1):2–6. doi: 10.1097/00128360-200501000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosgraaf RP, et al. Overtreatment in a see-and-treat approach to cervical intraepithelial lesions. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(6):1209–16. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318293ab22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho H, Kim JH. Treatment of the patients with abnormal cervical cytology: a “see-and-treat” versus three-step strategy. J Gynecol Oncol. 2009;20(3):164–8. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2009.20.3.164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holschneider CH, Ghosh K, Montz FJ. See-and-treat in the management of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions of the cervix: a resource utilization analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94(3):377–85. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00337-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bigrigg MA, et al. Colposcopic diagnosis and treatment of cervical dysplasia at a single clinic visit. Experience of low-voltage diathermy loop in 1000 patients. Lancet. 1990;336(8709):229–31. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)91746-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jakobsson M, et al. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure and the risk for preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(3):504–10. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b052de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sadler L, et al. Treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and risk of preterm delivery. JAMA. 2004;291(17):2100–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruinsma FJ, Quinn MA. The risk of preterm birth following treatment for precancerous changes in the cervix: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BJOG. 2011;118(9):1031–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.02944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moscicki AB, et al. Rate of and risks for regression of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 in adolescents and young women. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(6):1373–80. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fe777f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katki HA, et al. Five-year risk of CIN 3+ to guide the management of women aged 21 to 24 years. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(5 Suppl 1):S64–8. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3182854399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.A.C. Society, editor. Society., A.C. Cancer Facts & Figures 2014. Atlanta: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Freeman HP, Wingrove BK, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities (U.S.) Excess cervical cancer mortality : a marker for low access to health care in poor communities : an analysis. Rockville, MD: National Cancer Institute, Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities; p. 79. (NIH pub. 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alabama Cancer Facts & Figures 2012. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Samson SL, et al. The effect of loop electrosurgical excision procedure on future pregnancy outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):325–32. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000151991.09124.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Conner S. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure and risk of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(4):752–761. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katki HA, et al. Cervical cancer risk for women undergoing concurrent testing for human papillomavirus and cervical cytology: a population-based study in routine clinical practice. Lancet Oncol. 12(7):663–72. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70145-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]