Abstract

Rationale

Mutations in desmosome proteins cause arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (AC), a disease characterized by excess myocardial fibro-adipocytes. Cellular origin(s) of fibro-adipocytes in AC is unknown.

Objective

To identify the cellular origin of adipocytes in AC.

Methods and Results

Human and mouse cardiac cells were depleted from myocytes and flow sorted to isolate cells expressing platelet-derived growth factor receptor A (PDGFRA) and exclude those expressing other lineage and fibroblast markers (CD32, CD11B, CD45, Lys76, Ly−6c and Ly6c, THY1, and DDR2). The PDGFRApos:Linneg:THY1neg:DDR2neg cells were bipotential, as the majority expressed COL1A1, a fibroblast marker, and a subset CEBPA, a major adipogenic transcription factor, and therefore, were referred to as fibro-adipogenic progenitors (FAPs). FAPs expressed desmosome proteins including desmoplakin (DSP), predominantly in the adipogenic but not fibrogenic subsets. Conditional heterozygous deletion of Dsp in mouse using Pdgfra-Cre deleter led to increased fibro-adipogenesis in the heart and mild cardiac dysfunction. Genetic fate mapping tagged 41.4±4.1% of the cardiac adipocytes in the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice, indicating an origin from FAPs. FAPs isolated from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mouse hearts showed enhanced differentiation to adipocytes. Mechanistically, deletion of Dsp was associated with suppressed canonical Wnt signaling and enhanced adipogenesis. In contrast, activation of the canonical Wnt signaling rescued adipogenesis in a dose-dependent manner.

Conclusions

A subset of cardiac FAPs, identified by the PDGFRApos:Linneg:THY1neg:DDR2neg signature, expresses desmosome proteins and differentiates to adipocyte in AC through a Wnt-dependent mechanism. The findings expand the cellular spectrum of AC, commonly recognized as a disease of cardiac myocytes, to include non-myocyte cells in the heart.

Keywords: Adipocytes, progenitor cells, heart failure, cardiomyopathy, genetics

Subject Terms: Cardiomyopathy, Heart Failure

INTRODUCTION

Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy (AC) is an enigmatic hereditary disease characterized pathologically by excess fibro-adipocytes in the myocardium and clinically by ventricular arrhythmias, heart failure, and sudden death 1–3. Molecular genetic basis of AC has been partially elucidated. Mutations in genes encoding desmosome proteins, components of the intercalated disks, have been identified as the main causes of AC 2, 4. Cardiac myocytes (CMs), thus far, are the only cell type in the heart known to express desmosome proteins. However, CMs are differentiated cells and are not expected to switch fate and trans-differentiate to fibro-adipocytes. Thus, the molecular genetic discoveries have raised the intriguing question of how do mutations in the desmosome proteins; expressed in the heart, hitherto, only in CMs, lead to the unique phenotype of fibro-adipogenesis in the heart. We surmised that cells other than cardiac myocytes in the heart express desmosome proteins and differentiate to fibro-adipocytes in AC.

The heart is a cellularly heterogeneous organ, comprised of a number of mature and immature cells. Among the mature cells, CMs are the only cardiac cells that are known to express desmosome proteins. Among the resident progenitor cells, KIT+ cells have been shown to express junction protein plakoglobin (JUP), a component of the desmosomes, and differentiate to adipocytes 5. However, KIT+ progenitors are scant in the heart and contribute only to a small fraction of the excess adipocytes in AC 5. It is unknown whether desmosome proteins are also expressed in other resident mature and progenitor cells in the heart.

A subset of resident skeletal muscle progenitor cells, commonly identified by the expression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α (PDGFRA), are considered to be fibro-adipocyte progenitors (FAPs) 6–8. Skeletal FAPs are bipotential cell types that under physiological states are quiescent but upon muscle injury are activated to facilitate muscle regeneration by the endogenous myogenic stem cells 6–9. Persistent injury or failure of the skeletal muscle to regenerate following injury leads to differentiation of the FAPs to fibroblasts and adipocytes 6–8. Therefore, we surmised that the heart, similar to skeletal muscles, might contain a subset of resident progenitor cells, which could differentiate to adipocytes in AC. However, the presence and characteristics of the cardiac FAPs and/or their differentiation to adipocytes in the heart have yet-to-be demonstrated. Such progenitor cells, in the context of AC, have to express the desmosome proteins in order to differentiate to adipocytes in the presence of the mutant desmosome protein in AC. Alternatively, such cells could differentiate to adipocytes through paracrine mechanisms, emanating from myocytes that express the mutant desmosome protein. The present study is designed to identify and characterize cardiac progenitor cells that differentiate to adipocytes in AC and determine the responsible mechanism(s).

METHODS

The investigation conforms to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and Review Board approved the studies. A detailed Material and Methods section is provided in the Online supplementary material.

Isolation and characterization of human and mouse cardiac FAPs

Steps taken to isolate cardiac FAPs are shown in Online Figure I. In brief, non-cardiac myocyte fraction of heart cells was sorted to isolate cells that express PDGFRA and exclude those expressing hematopoietic lineage markers CD32, CD11B, CD45, Lys76, Ly−6c and Ly6c (Linneg), stem cell and fibroblast marker THY1, and fibroblast marker DDR2. The isolated mouse PDGFRApos:Linneg:THY1neg:DDR2neg cells were also analyzed for the expression of lineage markers TIE2, PDGFRB, CD146, and KIT antigen by flow cytometry and/or immunostaining.

Isolation of mouse adult cardiac myocytes (CMs)

To isolate CMs, explanted mouse heart was perfused with a calcium free perfusion media and a digestion buffer containing collagenase II 10. CMs were isolated from the digested tissue by filtration and low speed centrifugation and were gradually introduced to calcium at the final concentration of 1.5 mM. CMs were plated in culture dishes or cover glasses coated with laminin and incubated immediately in a 2% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The isolation procedure is expected to exclude non-myocyte cardiac cells 10.

Isolation and culture of smooth muscle cells (SMCs), endothelial cells (ECs), and cardiac fibroblasts (CFs)

Mouse aortic SMCs were isolated from the mouse aortic tissues and cultured as previously published 11. Mouse primary cardiac microvascular ECs were purchased from a commercial source and grown on plates pre-coated with gelatin-based coating solution in M1168 mouse endothelial cell growth medium. Cardiac fibroblasts were isolated as previously published 12.

Immunofluorescence (IF), immunoblotting (IB), immunohistochemistry (IH), and quantitative PCR (qPCR)

IF, IB, IH, and qPCR were performed, as published 13–15.{Lim, 2001 #103}.

Detection of apoptosis: Apoptosis was detected by TUNEL assay, as previously described 16.

Lineage tracer mice: Pdgfra:Egfp reporter mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory 17.

These mice express the H2B-eGFP fusion protein from the endogenous Pdgfra locus, leading to expression of H2B-eGFP mimicking the expression pattern of the endogenous Pdgfra gene 17. Myh6-Cre, DspF/F and R26-FSTOPF-Eyfp mice have been published 16, 18–21. Pdgfra-Cre BAC transgenic mice were from Jackson Laboratory. Oligonucleotide primers used in genotyping by PCR are listed in Online Table I.

Echocardiography

Left ventricular dimensions and function in mice were assessed by B-mode, M-mode and Doppler echocardiography using a HP 5500 Sonos echocardiography unit equipped with a 15-MHz linear transducer, as published 5, 14, 15. Wall thicknesses and left ventricular (LV) dimensions were measured from M-mode images using the leading-edge method on 3 consecutive cardiac cycles. LV fractional shortening and mass were calculated as previously described 5, 14, 15.

Morphometric and histological analyses

Ventricular/body weight ratio, H&E, Masson Trichrome, Picrosirius Red, and Oil Red O staining were analyzed, as published 5, 14, 15. To quantify extent of fibrosis, collagen volume fraction (CVF) was determined from Sirius Red stained thin myocardial sections using ImageTool 3.0 software.

Induction of adipogenesis

Isolated cardiac FAPs were treated with an Adipogenesis Induction Medium for 2 to 7 days, as published 5, 14, 15.

Activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway

To activate the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, cells were treated with 2 different concentrations (5 and 10 μM) of 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime (BIO), a known activator of the canonical Wnt signaling, as described 5, 22, 23.

Statistical analysis

Normally distributed continuous variables between the two groups were compared by t-test or Mann-Whitney U test. Differences among multiple groups were analyzed by one-way ANOVA or multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA). Pairwise comparisons were performed by Bonferroni multiple comparisons test. Differences among the categorical values were compared by Kruskall-Wallis test.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of cardiac FAPs

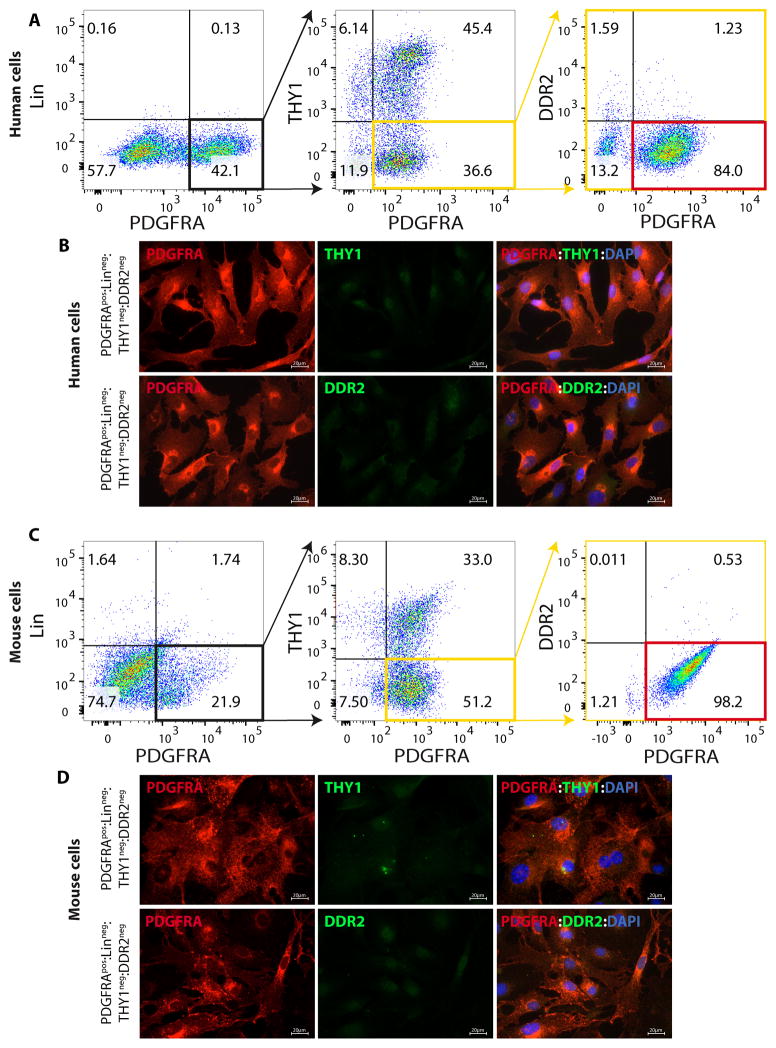

A subset of progenitor cells in skeletal muscles, referred to as FAPs, are characterized by the expression of cell surface marker PDGFRA and exclusion of other cell types known to express PDGFRA, such as bone marrow-derived progenitors 6, 8, 24, 25. In the heart presence and characteristics of FAPs and the subset that differentiate to adipocytes are unknown. To isolate cardiac FAPs, human and mouse myocyte-depleted cardiac cells were sorted by flow cytometry to isolate cells that expressed PDGFRA but not the hematopoietic progenitor markers CD32, CD11B, CD45, Lys76, Ly−6c and Ly6c, stem cell and fibroblast marker THY1, or fibroblast marker DDR2 (Figure 1 and Online Figure I). The findings were also corroborated by IF staining of human and mouse FACS isolated PDGFRApos;Linneg;THY1neg;DDR2neg cells for the lack of expression of THY1 and DDR2 (Figure 1). Myocyte-depleted cardiac cells were analyzed for co-expression of PDGFRA and additional lineage markers TIE2; a marker for endothelial cells, KIT antigen; a marker for progenitor cells, CD146; a marker for pericytes, and PDGFRB; a marker for progenitor cells and pericytes. As shown in Online Figure II, less than 1% of cardiac PDGFRApos cells expressed TIE2, KIT, CD146, and PDGFRB lineage markers.

Figure 1. Isolation of FAPs from human and mouse hearts.

A, C. Flow cytometry plots showing the multi-step approach used to isolate FAPs from human (A) and mouse (C) hearts: non-myocyte fraction of cardiac cells were sorted to isolate cells positive for PDGFRA but negative for the hematopoietic progenitor markers CD32, CD11B, CD45, Lys76, Ly-6c and Ly6c, the stem cell and fibroblast marker THY1, and the fibroblast marker DDR2. Positive gates were set by analyzing signals from negative control samples, which were stained only with the corresponding IgG isotype for each marker. B, D. Immunofluorescence panels confirming the lack of expression of THY1 and DDR2 in human (B) and mouse (D) FACS isolated PDGFRApos:Linneg:THY1neg:DDR2neg cells.

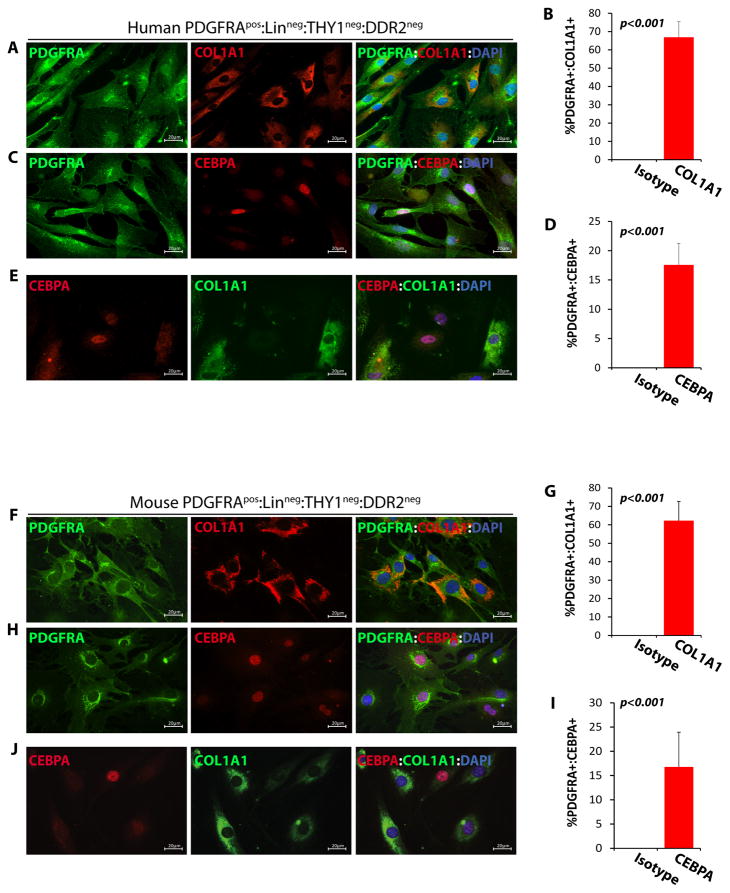

To determine whether isolated human and mouse PDGFRApos:Linneg:THY1neg:DDR2neg cells were bipotential for fibrogenesis and adipogenesis, similar to FAPs in skeletal muscles, they were stained for the expression of COL1A1 and CEBPA, markers for fibrogenesis and adipogenesis, respectively. As shown in Figure 2, PDGFRApos:Linneg:THY1neg:DDR2neg cells showed bimodal expression patterns of these two markers, as the majority predominantly expressed COL1A1 COL1A1 (62.3 ± 10.4% in mouse; 66.9 ± 8.5 in human) and a minority subset (16.8 ± 7.2% in mouse; 17.6±3.7 in human) predominantly expressed CEBPA (Figure 2). These findings collectively suggest PDGFRApos:Linneg:THY1neg:DDR2neg cells isolated from the heart are bipotential cells, expressing either adipogenic or fibrogenic markers. Henceforth, they were referred to as cardiac FAPs.

Figure 2. Fibrogenic and adipogenic potential of FAPs isolated from the human and mouse hearts.

A–H. IF staining and relative quantifications of human (A–D) and mouse (F–I) cardiac FAPs, identified by expression of PDGFRA (in green), for the fibrogenic marker COL1A1 (A, F) and the adipogenic marker CEBPA (C, H) (both in red). About 65% of FAPs expressed COL1A1 (B, 66.9±8.5%, N=4, ~150 cells counted in each experiment in human; G, 62.3 ± 10.4%, N=8, ~200 cells counted in each experiment in mouse: N=8) while a smaller percentage expressed CEBPA (D, 17.6±3.7% in human; I, 16.8 ± 7.2% in mouse). E, J. Co-Immunofluorescence staining of human (E) and mouse (J) cardiac FAPs for COL1A1 and CEBPA showing that a subset of FAPs express COL1A1, but not CEBPA and another subset express CEBPA but not COL1A1.

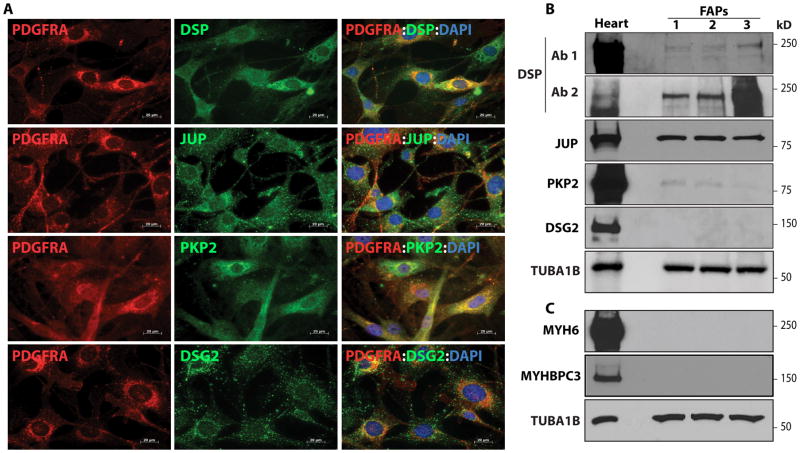

Expression of desmosome proteins in FAPs

To determine whether cardiac FAPs express desmosome proteins, expressions of Desmoplakin (DSP), junction protein plakoglobin (JUP), plakophilin 2 (PKP2), and desmoglein 2 (DSG2) were determined by IF and IB 2, 26. As shown in Figure 3, DSP, JUP, PKP2, and DSG2 were expressed in cardiac FAPs(Figure 3). To exclude potential contamination of the isolated FAPs with CMs, hitherto, the only cardiac cell type known to express desmosome proteins, isolated cardiac FAPs cells were examined for the expression of sarcomere proteins myosin heavy chain 6 (MYH6) and myosin binding protein C3 (MYBPC3). As shown in Figure 3, MYH6 and MYBPC3 were not expressed in cardiac FAPs, indicating that the isolates were devoid of contamination with CMs.

Figure 3. Expression of desmosome proteins in FAPs isolated from the mouse heart.

A, B. Detection of expression of desmoplakin (DSP, 2 different antibodies), junction protein plakoglobin (JUP), plakophilin 2 (PKP2) and desmoglein 2 (DSG2) by immunofluorescence (A) and immunoblotting (B) in FACS isolated cardiac FAPs. C. Absence of expression of the sarcomeric proteins MYH6 and MYBPC3 in isolated FAPs by immunoblotting to exclude potential contamination with CMs. Heart tissue is included as a positive control.

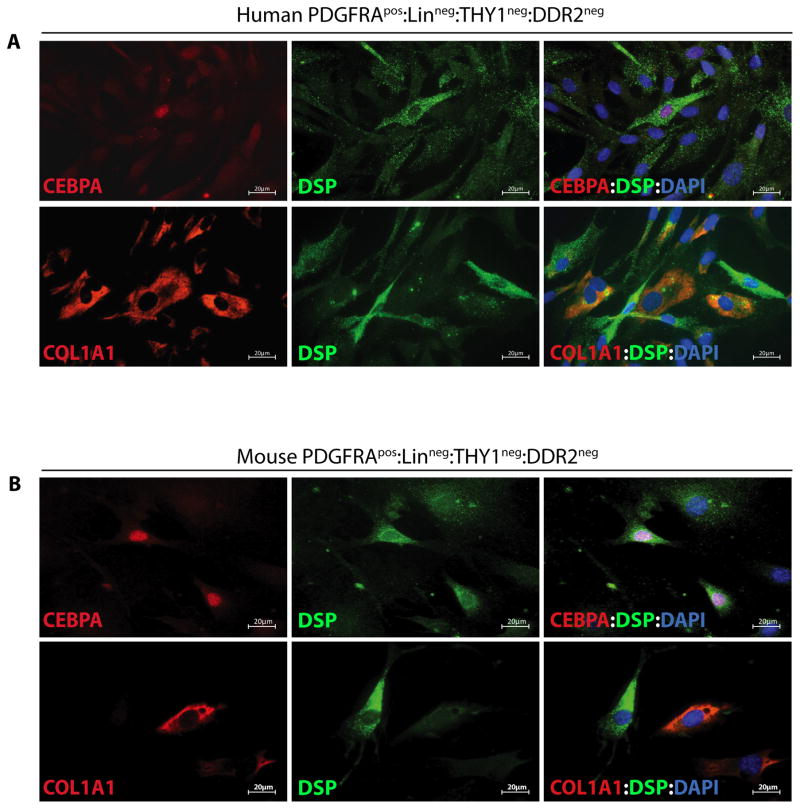

Expression of DSP protein in cardiac adipogenic FAPs

To determine whether both subpopulations of cardiac FAPs expressed DSP, isolated human and mouse PDGFRApos:Linneg:THY1neg:DDR2neg cells were co-stained for the expression of DSP and CEBPA or COL1A1. As shown in Figure 4, DSP protein was predominantly co-expressed with CEBPA but not with COL1A1.

Figure 4. Expression of DSP protein predominantly in adipogenic FAPs from human and mouse heart.

A, B. Co-IF staining for the expression of DSP and CEBPA or COL1A1 in cardiac FAPs from human (A) and mouse (B). DSP protein was predominantly co-expressed with CEBPA but not with COL1A1 in both, human and mouse cells.

Expression of PDGFRA in other cardiac cell types

As a prelude to genetic fate mapping, we determined whether PDGFRA was expressed in other major cardiac cell types, namely, CMs, CFs, SMCs, and ECs. Neither CMs, ECs, nor SMCs expressed PDGFRA protein as detected by IF staining of isolated cells and IB of extracted proteins (Online Figure III). Likewise, Pdgfra mRNA was undetectable in isolated adult CMs (Online Figure IIIC). In contrast 71.1 ± 20.2 % of isolated CFs, identified by the expression of COL1A1, also expressed PDGFRA (Online Figure III), a finding that is in accord with the literature and immunostaining of the FAPs for COL1A1 (Figure 2) 27–29. In accord with these findings, immunostaining of thin mouse myocardial sections also showed expression of the PDGFRA in CFs but not in CMs. SMCs, or ECs (Online Figure IV).

In a complementary set of studies and to corroborate detection of expression of PDGFRA in cardiac cell types, we determined expression of the reporter protein enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) in the heart in the Pdgfra-Egfp reporter mice. In this model expression of EGFP is transcriptionally regulated by the Pdgfra locus 17. Approximately 51.3 ± 9.8% of CFs was tagged with the EGFP (Online Figure V), a finding that was in accord with the expression of PDGFRA in isolated adult CFs (Online Figure III) and immunostaining of cardiac FAPs for COL1A1 (Figure 2). However, expression of the reporter protein EGFP was not detected in CMs, SMCs, and ECs, indicating that Pdgfra locus was transcriptionally inactive in these mature cardiovascular cells (Online Figure V).

Absence of expression of DSP in CFs, SMCs, and ECs

To determine whether DSP was expressed in CFs, ECs, and SMCs in the heart, isolated murine CFs, SMCs, and ECs were stained for the expression of DSP and analyzed by IB. As shown in Online Figure VI, DSP protein was not expressed in isolated CFs, SMCs, and ECs, while it was expressed in isolated cardiac myocytes, as expected.

Lineage tracing upon genetic deletion of Dsp gene in cardiac FAPs

To determine whether deficiency of DSP affects differentiation of FAPs to adipocytes, Dsp gene was conditionally deleted upon expression of cre recombinase in cardiac FAPs. In this strategy, crossing of Pdgfra-Cre deleter with DspF/F:R26-FSTOPF-Eyfp mice led to expression of the cre recombinase in cardiac FAPs, deletion of the floxed exon 2 of the Dsp gene, and deletion of the STOP sequence upstream of the Eyfp gene. The former led to inactivation of Dsp and the latter to expression of EYFP in FAPs in the Pdgfra-Cre:R26-FSTOPF-Eyfp:DspW/F lineage tracer mice (hitherto Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F) (Online Figure VII).

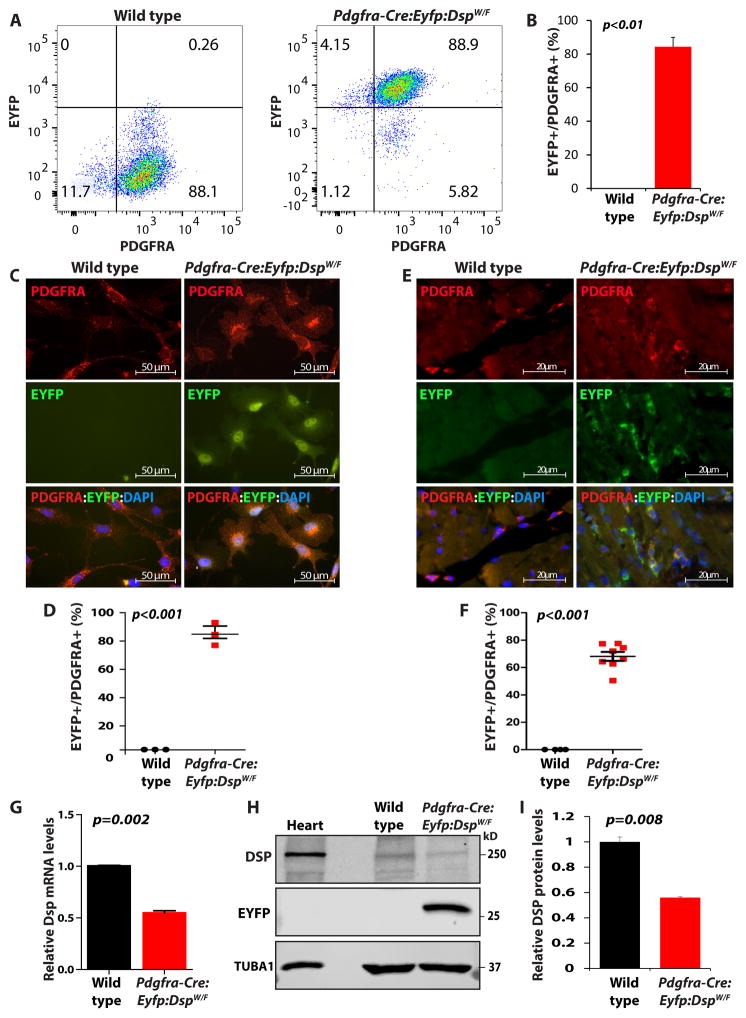

To determine efficiency of the cre-mediated recombination, FAPs were isolated from the hearts of Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F lineage tracer mice and analyzed by flow cytometry for the expression of EYFP, as an indicator of recombination efficiency (Figure 5A and B). Expression of EYFP was detected in ~ 84.3 ± 5.6 % of the cardiac FAPs (Figure 5). Direct examination of isolated cardiac FAPs under fluorescence microscopy also confirmed expression of EYFP in 84.8 ± 7.9% of the isolated FAPs (Figure 5). To complement the data on the recombination efficiency, thin myocardial sections from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F lineage tracer mice were co-stained for the expression of PDGFRA and EYFP. Approximately 68.2 ± 9.2% of PDGFRA expressing cells also expressed EYFP (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Efficiency of the cre-mediated recombination in the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F lineage tracer mice.

A. Expression of enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (EYFP)) in FAPs isolated from the heart of wild type and Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F lineage tracer mice by FACS. B. Quantitative data showing expression of EYFP in 84.3 ± 5.6 % of the FAPs isolated from the heart of the lineage tracer mice (N=5). C. Direct fluorescence microscopic panels showing expression of the reporter protein EYFP in FAPs isolated from the heart of the lineage tracer mice. D. Quantitative data from 3 independent isolates showing detection of EYFP in ~ 85% of the isolated FAPs. E, F. Expression of EYFP in thin myocardial sections from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F lineage tracer mice (E). Quantitative data (F) show that about 68% of cells expressing PDGFRA also expressed EYFP (N=8 mice per group; 3 sections per mouse, 15 fields of 63X magnification per section). G–I. qPCR data and immunoblot showing reduced Dsp mRNA (G) and DSP protein levels (H, I) by approximately 50 % in cardiac FAPs isolated from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F lineage tracer mice, as compared to cardiac FAPs from the control mice (N=3).

To determine functional deletion of the Dsp gene in cardiac FAPs, mRNA and protein levels of Dsp were determined by qPCR and IB, respectively. Transcript levels of Dsp were reduced by 52.8 ± 3.3 % and that of DSP protein by approximately 56.0 ± 0.7 % in cardiac FAPs isolated from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F lineage tracer mice as compared to control mice (Figure 5).

To exclude fortuitous deletion of Dsp in other cardiac cells in the lineage tracer mice, mRNA and protein levels of Dsp gene as well as expression of EYFP were determined in CMs isolated from the hearts of WT and Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice. Surprisingly, 17.9 ± 0.3 % of CMs isolated from the hearts of Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice expressed EYFP suggesting, to our knowledge for the first time, developmental heterogeneity of CMs in the mouse heart (Online Figure VIII). The finding suggests transcriptional activity of the Pdgfra locus in a subset of CMs during development. To determine, whether genetic tagging of a subset of CMs under the transcriptional activity of the Pdgfra locus affected expression levels of Dsp mRNA and protein, their levels were quantified in isolated CMs. Dsp mRNA and protein levels were not significantly altered in CMs isolated from the lineage tracer mice as compared to control CMs (Online Figure VIII). Likewise, IF staining of isolated CMs showed localization of DSP to the junctional areas (Online Figure VIII). Considering that adult CMs do not express PDGFRA (Online Figures III, IV, and V), tagging of a subset of CMs with EYFP in the reporter mice suggests transient transcriptional activity of the Pdgfra locus during CM development but not persistent active transcription.

Expression of EYFP was also analyzed in myocardial sections from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice stained for EYFP and specific markers for CFs, SMCs and ECs. Only CFs but not SMCs or ECs expressed EYFP (Online Figure IX). This finding is in accord with the data in the Pdgfra-Egfp reporter mice (Online Figure V) as well as with the data showing in vitro and in vivo expression of PDGFRA in isolated CFs from wild type mice (Online Figures III and IV)

Phenotypic consequences of deletion of Dsp in cardiac FAPs

Echocardiographic data on left ventricular dimensions and function in 9 months old wild type, Pdgfra-Cre, and Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice are shown in Online Table II. As shown, Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice exhibited mild cardiac dilatation and dysfunction as compared to wild type and Pdgfgra-Cre control mice. There was no discernible cardiac dysfunction in the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp or R26-FSTOPF-Eyfp or DspF/F mice.

Ventricular/body weight ratio was modestly increased in the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice as compared to wild type mice or Pdgfra-Cre mice (Online Figure X). Picrosirius staining of thin myocardial sections showed increased myocardial interstitial fibrosis in the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice, comprising 3.8 ± 1.1 % of the myocardium (Online Figures X and XI). Similarly, Oil Red O staining of thin myocardial sections showed a 13 ± 8 -fold increase in the number of adipocytes in the heart of the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice, as compared to control mice (Online Figures X and XI). Moreover, the number of cells expressing adipogenic transcription factor CEBPA was also increased significantly in the hearts of Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice, as compared to the control groups (Online Figure XD and G and Figure XI). To further explore fibro-adipogenesis, FAPs were isolated from wild type and Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mouse hearts and along with thin myocardial sections were stained for pro-fibrotic transforming growth factor β1 (TGFB1). As shown in Online Figure XII, TGFB1 expression levels were increased in isolated FAPs and myocardial sections from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice. Finally, considering that deletion of Dsp in cardiac myocytes induces apoptosis 16, we determined whether deletion of Dsp in cardiac FAPs also induced apoptosis. The number of cells stained positive in the TUNEL assay was not significantly different between the wild type and Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice (Online Figure XIII).

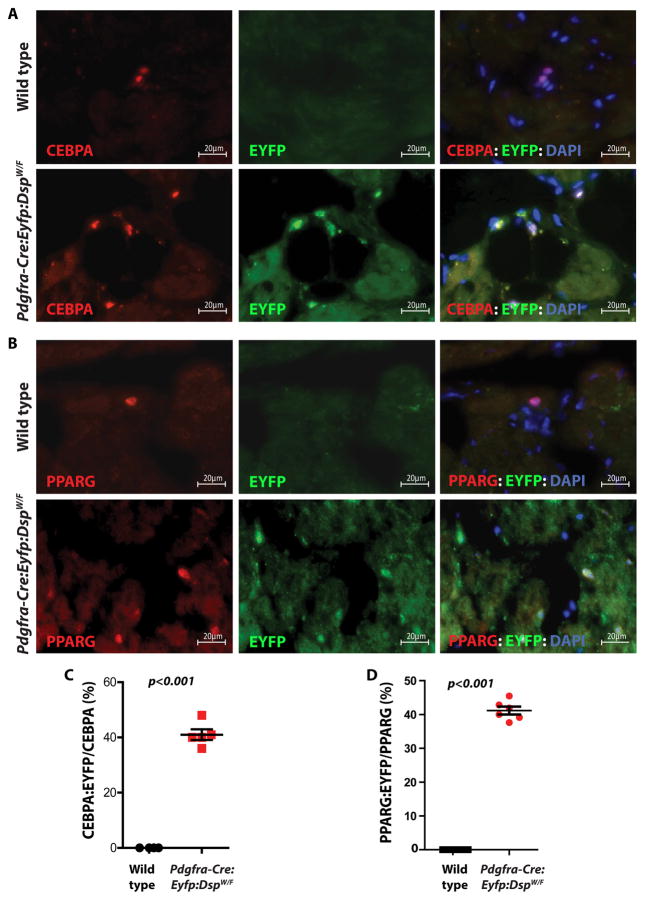

Origin of adipocytes from cardiac FAPs

To determine whether excess adipocytes in the heart originated from FAPs, thin myocardial sections were immunostained with antibodies against EYFP and adipogenic transcription factors CEBPA or PPARG. Approximately 41.4 ± 4.1 % of cells in the heart of lineage tracer mice that expressed CEBPA also expressed EYFP (Figure 6). The results were similar for the co-expression of PPARG and EYFP (41.2 ± 2.6 %) as shown in Figure 6. These data collectively indicate that close to half of the excess adipocytes in DSP-deficient mouse model originate from FAPs. To determine whether increased number of adipocytes in the heart of Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice was because of proliferation of the adipocytes, thin myocardial sections were co-stained for the expression of CEBPA, to mark adipocytes, and Ki67 protein (MKI67), to mark proliferating cells. As shown in Online Figure XIV, while the number of adipocytes was greater in the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice, percent of adipocytes that were stained positive for the proliferation marker did not differ significantly between the wild type and lineage tracer mice.

Figure 6. FAPs are a cell source of excess adipocytes in the heart of the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F lineage tracer mice.

A, B. Immunofluorescence panels showing co-expression of the reporter protein EYFP and the adipogenic markers CEBPA (A) and PPARG (B) in the myocardium of wild type and Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F lineage tracer mice. Thin myocardial sections from wild type mice were included as controls. Approximately 41±4 % of cells expressing CEBPA also expressed EYFP in the heart of lineage tracer mice (C) (N=5 mice per group; 4 sections per mouse, 20 fields of 63X magnification per section). Similarly, 41±3 % of the cells that expressed PPARG also expressed EYFP (D) (N=6 mice per group; 4 sections per mouse, 20 fields of 63X magnification per section). The data indicate genetic labeling of the adipocytes by the Pdgfra locus in the heart of the lineage tracer mice.

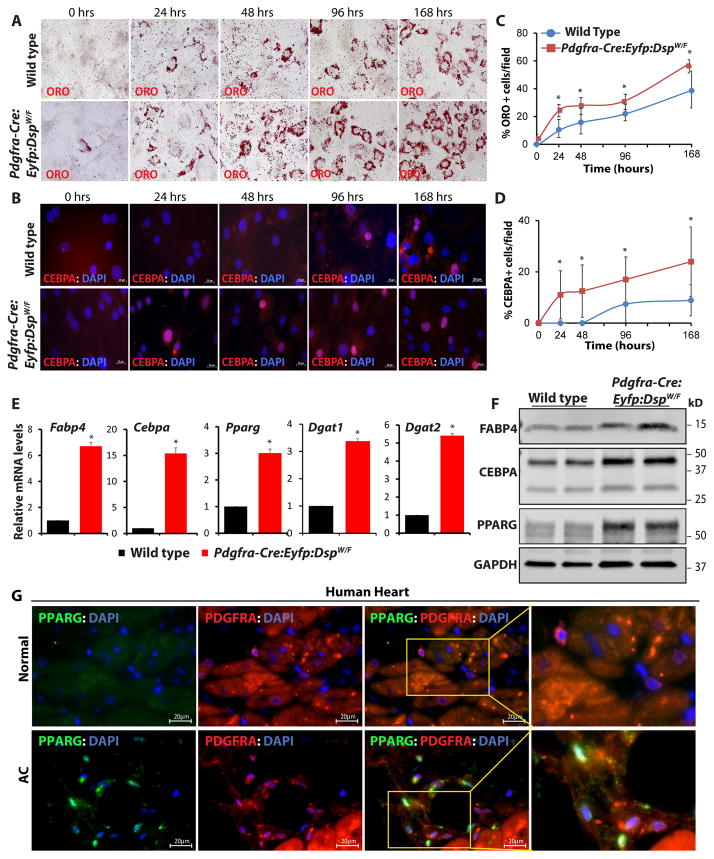

Enhanced differentiation of Dsp-deficient FAPs to adipocytes

To further support differentiation of cardiac FAPs to adipocytes, FAPs were isolated from the hearts of wild type and Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice and treated with an adipogenic induction medium, as published 5, 13. Adipogenesis was analyzed serially at multiple time points by quantifying the number of Oil Red O and CEBPA stained cells. The number of Oil Red O- and CEBPA-stained cells (Figure 7) was consistently higher in cardiac FAPs isolated from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice as compared to cells isolated from the wild type mice at all time points. Likewise, quantification of transcript levels of selected adipogenic genes by qPCR showed marked increases in the transcript levels of Fabp4, Cebpa, Pparg, Dgat1, and Dgat2 in FAPs isolated from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F as compared to control mice (Figure 7). Similarly, protein levels of FABP4, CEBPA, and PPARG were increased in FAPs isolated from the lineage tracer mice (Figure 7). To corroborate the findings based on Oil Red O staining, cells were stained for perilipin, a marker of mature adipocytes. The number of cells expressing perilipin was significantly increased in the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F as compared to wild type mice (Online Figure XV).

Figure 7. Enhanced adipogenesis in cardiac FAPs isolated from the DSP haplo-insufficient mice and detection of adipogenic FAPs in the human heart.

A, B. Oil Red O staining and CEBPA immunostaining showing accumulation of fat droplets (A) and expression of the adipogenic transcription factor CEBPA (B) in cardiac FAPs isolated from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F lineage tracer mice, as compared to wild type mice, at 4 time points upon induction of adipogenesis with insulin, IBMX and DXM. C, D. quantitative data showing increased number of mature (ORO+) adipocytes (C) and CEBPA+ cells (D) in the cardiac FAPs from the transgenic mice as compared with wild type mice at each time point (N=3, ~300 cells counted at each time point for each group, *p<0.05). E. qPCR data for selected adipogenic genes after 4 days of adipogenesis induction showing marked increase in the transcript levels of Fabp4, Cebpa, Pparg, Dgat1, and Dgat2 in cardiac FAPs isolated from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp: DspW/F mice as compared to wild type mice (N=3, * p<0.05). F. Immunoblots showing increased protein levels of adipogenic markers FABP4, CEBPA, and PPARG in cardiac FAPs isolated from the heart of lineage tracer mice after 4 days of adipogenic induction. G. Immunofluorescence stained panels from a control human heart and a human heart from a patients with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (AC), showing co-expression of PDGFRA and the adipogenic transcription factor PPARG, suggestive of the presence of FAPs in transition to adipocytes in the human heart with AC.

To extend the findings in the mouse models to human AC, thin myocardial sections from the hearts of human patients with AC were stained for the expression of PDGFRA and the adipogenic transcription factors PPARG (Figure 7G). Approximately 43.6 ± 0.8 % of adipocytes in the human hearts with AC co-expressed PDGRFA and PPRAG, suggesting a transitional state of cardiac FAPs to adipocytes in the human hearts with AC.

Exclusion of a paracrine mechanism for differentiation of cardiac FAPs to adipocytes

Considering that CMs are the main cardiac cells that are known to express desmosome proteins and given that lineage tracing identified about half of the adipocytes as originating from FAPs, a new set of lineage tracing was performed to test for paracrine mechanisms in differentiation of FAPs to adipocytes in AC. According to the paracrine hypothesis, the stimulus has to originate from cells that express desmosome proteins, mainly CMs and target cardiac resident cells that differentiate to adipocytes. To test this hypothesis, Pdgfra-Egfp reporter mice, whereby EGFP is expressed under transcriptional regulation of the Pdgfra locus, was crossed to the Myh6-Cre:DspW/F mouse model of AC. These mice are heterozygous for Dsp in CMs. The Pdgfra-Egfp:Myh6-Cre:DspW/F mice afford the opportunity to test a paracrine effect(s), emanating from the Dsp-deficient CMs and targeting resident EGFP-labeled FAPs for differentiation to adipocytes. Cardiac phenotype in the Pdgfra-Egfp:Myh6-Cre:DspW/F lineage tracer mice was comparable to that published for the Myh6-Cre:DspW/F mice 16. As would be expected, the phenotype was notable for enhanced fibro-adipogenesis and cardiac dysfunction (Online Figure XVI and Online Table III).

To detect whether adipocytes in the heart of Pdgfra-Egfp:Myh6-Cre:DspW/F expressed EGFP, thin myocardial sections were stained for EGFP and CEBPA. The findings are notable for the increased number of adipocytes in the hearts of Pdgfra-Egfp:Myh6-Cre:DspW/F mice (Online Figure XVII,), which is in accord with the finding in the Myh6-Cre:DspW/F mice 16. However, the percentage of adipocytes expressing EGFP in the control Pdgfra-Egfp and Pdgfra-Egfp:Myh6-Cre:DspW/F mice was not significantly different (Online Figure XVII). The finding excludes differentiation of cardiac FAPs to adipocytes due to paracrine effects of Dsp-deficient CMs.

Suppression of the canonical Wnt signaling as a mechanism for enhanced differentiation of cardiac FAPs to adipocytes

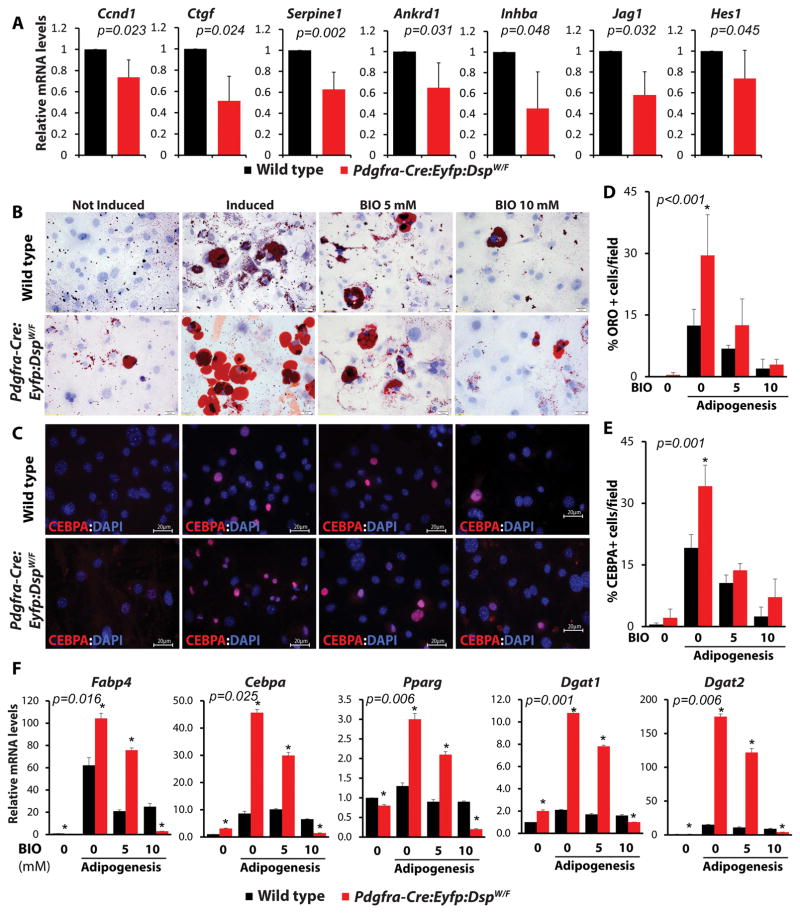

Because canonical Wnt signaling, a major determinant of cell fate and differentiation, has been previously implicated in the pathogenesis of adipogenesis in AC 5, 13, 16, transcript levels of established targets of the canonical Wnt signaling pathways in the heart were analyzed by qPCR. As shown in Figure 8, transcript levels of several canonical Wnt target genes were significantly reduced in the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice.

Figure 8. Suppression of the canonical Wnt and rescue of adipogenesis upon activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway.

A. qPCR quantification of the transcript levels of established targets of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway showing reduced levels in the heart of Pdgfra-Cre: Eyfp: DspW/F lineage tracer mice, as compared to wild type control mice (N=3 mice per group). B–E. Rescue of adipogenesis upon activation of the canonical Wnt pathway. ORO stained (B) and CEBPA immunostained (C) panels showing FAPs isolated from the heart of wild type and Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice, subjected to adipogenic stimulation and treated with 2 doses of BIO, a known activator of the Wnt signaling. Quantitative data (panels D and E) show activation of the canonical Wnt signaling reduced adipogenesis in a dose-dependent manner (N=3, ~300 cells for ORO, ~200 cells for CEBPA-IF counted in each experiment for each group). F. qPCR data showing transcript levels of selected genes involved in adipogenesis prior to induction of adipogenesis, upon induction with adipogenic media and following treatment with two increasing concentrations of BIO. Treatment with BIO normalized increased transcript levels of the adipogenic genes Fabp4, Cebpa, Pparg, Dgat1, and Dgat2 in FAPs isolated from the heart of Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice in a dose-dependent manner (N=3 for each experiment,*p< 0.05).

To determine the pathogenic role of suppressed canonical Wnt signaling in differentiation of Dsp-deficient FAPs to adipocytes, FAPs were isolated from the hearts of Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp DspW/F mice, and treated with 6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime (BIO) to activate the canonical Wnt signaling 5, 23. Treatment with BIO rescued adipogenesis in FAPs in a dose-dependent manner, as determined by Oil Red O and IF staining for CEBPA (Figure 8). Likewise, treatment of cardiac FAPs, isolated from the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp DspW/F mice, with BIO normalized transcript levels of several adipogenic genes (Figure 8).

DISCUSSION

A subset of human and mouse resident cardiac progenitor cells, identified as PDGFRA pos:Linneg:THY1neg:DDR2neg cells, referred to as cardiac FAPs, is a major source of adipocytes in AC caused by Dsp haploinsufficiency. Cardiac FAPs exhibit bimodal expression patterns for the adipogenic transcription factor CEBPA and the fibroblast marker COL1A1. Desmosome proteins including DSP are expressed only in a subset of FAPs that predominantly express CEBPA but not in cells expressing COL1A1. Genetic deletion of Dsp in cardiac FAPs leads to their differentiation to adipocytes in the mouse heart through a canonical Wnt-dependent mechanism. Cardiac FAPs give origin to ~ 40% of the adipocytes in the heart of a mouse model of AC, a finding that indicates a heterogeneous cellular origin of excess adipocytes in AC. Thus, the finding of the present study by showing expression of desmosome proteins in cardiac FAPs expand the cellular basis of AC, which is conventionally considered a disease of CMs, to include non-myocyte cells, namely FAPs, in the heart.

Multiple cell surface and lineage-specific markers were used to identify and isolate cardiac FAPs in the human as well as in the mouse hearts. Likewise, expression of multiple desmosome proteins were detected in cardiac FAPs and confirmed by complementary methods. The data also show two distinct subsets of FAPs with regards to expression of the adipogenic and fibrogenic markers, likely serving as progenitors for their respective lineages. Notably desmosome protein DSP was predominantly expressed in the adipogenic but not the fibrogenic subset of cardiac FAPs. In accord with this observation, DSP was not expressed in CFs and other common cardiac cell types such as SMCs and ECs, a finding that was confirmed at multiple levels and in vitro studies as well as in vivo mapping studies using reporter mice. Thus, although a subset of CFs originate from cells transcriptionally regulated by the Pdgfra locus, CFs and a subset of FAPs that predominantly express COL1A1 do not express DSP. Therefore, in the genetic fate mapping studies expression of the cre recombinase under the transcriptional control of the Pdgfra locus is expected to lead to specific deletion of the Dsp gene in a subset of cardiac FAPs that express DSP but not in CFs and other cell types in the heart.

Because PDGFRA is also considered a fibroblast marker, we excluded cells expressing other fibroblast markers THY1pos and DDR2pos cells. Nevertheless, despite exclusion of such cells, approximately 70 % of cardiac FAPs also expressed COL1A1, which is a marker for CF lineage. Whether COL1A1pos cells are true fibroblast progenitor cells or mature CFs was not discerned in the presence study, as DSP, which was targeted for deletion, was not expressed in CFs or in the subset of COL1A1pos FAPs. Heterogeneous origin of CFs further cofounds their effective identification and isolation, by a defined set of markers 30. In accord with the data on the developmental heterogeneity of CFs 27–29, genetic fate mapping using the Pdgfra-Cre mice tagged approximately 50% of CFs as originating from cells that are transcriptionally regulated by the Pdgfra locus.

Approximately half of cardiac adipocytes in the Dsp heterozygous mice originated from cardiac FAPs. This finding might in part reflect an incomplete recombination efficiency, which was estimated to be ~ 80%. It also suggests a heterogeneous origin of the excess adipocytes in AC. We have previously shown that a small fraction of cardiac adipocytes originate from cells that express the KIT antigen 5. FAPs are distinct from KITpos cells, as shown in cell sorting and immunostaining data (Online Figure II). Thus, additional cell types including other mesenchymal progenitor cells might give rise to excess adipocytes. Alternatively, resident cardiac adipocytes might simply proliferate in response to yet-to-be defined mechanism(s) in AC. The latter seems unlikely, as the number of proliferating adipocytes were not significantly different between the wild type and the Dsp-deficient lineage tracer mice. It is also important to note that the mouse models of AC, caused by mutations in the desmosome proteins, do not truly recapitulate the human phenotype, as the extent of fibro-adipocyte infiltration in the myocardium is rather modest, as compared to AC in humans. Incomplete recapitulation of the human phenotype in model organisms is not unusual and rather expected 31, 32. Nevertheless, the finding of a subset of adipocytes in the hearts of human patients with AC co-expressing PDGFRA and PPARG offer additional credence to relevance of the findings to human AC.

An intriguing finding of the present study is the developmental heterogeneity of CMs. Accordingly, genetic fate mapping identified a minority fraction of CMs (~ 20%) that was transcriptionally regulated by the Pdgfra locus sometimes during development. Considering that PDGFRA is not transcriptionally active in adult CM, as shown by multiple sets of data in the present study, the finding indicates transient transcriptional activity of the Pdgfra locus during cardiac development and subsequent silencing of the locus in the adult CMs. It is important to note despite labeling of a subset of CMs with EYFP, protein and mRNA levels of Dsp gene were unchanged in CMs. This finding might simply indicate that heterozygous deletion of Dsp in ~ 20% of CMs is not sufficient to reduce levels of Dsp mRNA and protein in the whole heart, particularly considering transcriptional compensation from the wild type allele 33. In addition, a modest reduction might not be within the resolution of qPCR and IB. Nevertheless, the Pdgfra-Cre:Eyfp:DspW/F mice exhibited mild cardiac dilatation and dysfunction, which might reflect the role of FAPs in supporting cardiac function or the effects of modest and yet undetectable changes in the expression level of Dsp gene in ~ 20% of CMs. Biological and functional significance of developmental heterogeneity of CMs, nevertheless, remains to be determined.

The findings also implicate suppressed canonical Wnt signaling in the heart as a mechanism for enhanced differentiation of resident FAPs to adipocytes, which is also in accord with the previous findings 5, 13, 16. The mechanisms responsible for suppression of the canonical Wnt signaling were not directly tested in the present study but presumably are similar to those published 5, 13, 16. The second set of genetic fate-mapping, whereby EGFP protein was expressed under transcriptional activity of the Pdgfra locus in the background of deletion of Dsp gene in CMs, excluded a possible paracrine mechanism(s) for differentiation of FAPs to adipocytes in the Dsp-deficient mice. Mechanistic studies, however, are not comprehensive of various putative mechanisms that might be involved in the pathogenesis of AC and its perplexing histopathological phenotypes.

In summary, we have identified a subset of human and mouse resident cardiac progenitor cells, characterized by the expression of PDGFRA but lacking expression of other cell lineage markers, and referred to as cardiac FAPs, as a cell source of excess adipocytes in AC. A subset of cardiac FAPs that express adipogenic transcription factor CEBPA also express desmosome proteins including DSP and differentiate to adipocytes in a mouse model of AC caused by Dsp haplo-insufficiency, through a mechanism that involves the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. The findings expand the cellular basis of AC to include cardiac FAPs and indicate a heterogeneous cellular basis of the complex phenotype of AC.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What Is Known?

Arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (AC), an inherited genetic disease, is an important cause of sudden cardiac death in the young.

Mutations in genes encoding desmosome proteins cause AC.

Cardiac myocytes, hitherto, are the only cardiac cell type known to express desmosome proteins.

A Pathological hallmark of AC is excessive fibro-adipogenesis in the heart, which contributes to both cardiac dysfunction and arrhythmias.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

We have identified a subset of resident cardiac cells, fibro-adipocyte progenitors (FAPs), that express the cell surface marker platelet derived growth factor alpha receptor (PDGFRA), and exhibit a bimodal pattern for the expression of either an adipogenic transcription factor CEBPA or a fibroblast marker COL1A1.

The sub-fraction of cardiac FAPs that express adipogenic markers also express desmosome proteins, including DSP.

Deletion of Dsp gene in FAPs leads to their differentiation to adipocytes.

FAPs give origin to approximately half of the excess cardiac adipocytes in AC.

Canonical Wnt signaling pathway regulate differentiation of cardiac FAPs to adipocytes in AC.

We found that in addition to cardiac myocytes, desmosome proteins are expressed in t FAPs, and these cells contribute to the pathogenesis of the unique phenotype of fibro-adipogenesis in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Mr. Alon R. Azares for his technical support with FACS.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported in part by grants from NIH, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI, R01 HL088498, 1R01HL132401, and R34 HL105563), Leducq Foundation (14 CVD 03), Roderick MacDonald Foundation (13RDM005), TexGen Fund from Greater Houston Community Foundation, George and Mary Josephine Hamman Foundation, American Heart Association Beginning Grant in Aid (15BGIA25080008 to RL), and American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship (14POST18720013 to SNC).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AC

Arrhythmogenic Cardiomyopathy

- BIO

6-bromoindirubin-3′-oxime

- CD146

cluster of differentiation 146

- CEBPA

CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α

- CFs

Cardiac fibroblasts

- CMs

Cardiac myocytes

- COL1A1

Collagen 1 alpha 1

- CVF

Collagen volume fraction

- DAPT

N-[N-(3,5-Difluorophenacetyl)-L-alanyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester

- DDR2

Discoidin Domain Receptor 2

- DGAT1

Diacylglycerol O-Acyltransferase 1

- DGAT2

Diacylglycerol O-Acyltransferase 2

- DSC2

Desmocolin 2

- DSG2

Desmoglein 2

- DSP

Desmoplakin

- ECs

Endothelial cells

- EGFP

Enhanced green fluorescent protein

- FABP4

Fatty Acid Binding Protein 4

- FAPs

Fibro-adipocyte progenitors

- GFP

Green fluorescent protein

- IB

Immunoblotting

- IDs

Intercalated Disc

- IF

Immunofluorescence

- IH

Immunohistochemistry

- JUP

Junction protein plakoglobin

- KIT

KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase

- Lin

Lineage

- MSCs

Mesenchymal stem cells

- MYBPC3

Myosin binding protein C3

- MYH6

Myosin heavy chain 6

- PDGFRA

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α

- PDGFRB

Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-β

- PKP2

Plakophilin 2

- PPARG

Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma

- qPCR

Quantitative PCR

- ShRNA

Short hairpin RNA

- TGFB1

Transforming growth factor B1

- THY1

Thymocyte differentiation antigen 1

- TIE2

Endothelial-specific receptor tyrosine kinase

- TUNEL

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES

None.

References

- 1.Corrado D, Basso C, Thiene G, McKenna WJ, Davies MJ, Fontaliran F, Nava A, Silvestri F, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Wlodarska EK, Fontaine G, Camerini F. Spectrum of clinicopathologic manifestations of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: A multicenter study. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997;30:1512–1520. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delmar M, McKenna WJ. The cardiac desmosome and arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathies: From gene to disease. Circulation research. 2010;107:700–714. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.223412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Groeneweg JA, Bhonsale A, James CA, te Riele AS, Dooijes D, Tichnell C, Murray B, Wiesfeld AC, Sawant AC, Kassamali B, Atsma DE, Volders PG, de Groot NM, de Boer K, Zimmerman SL, Kamel IR, van der Heijden JF, Russell SD, Jan Cramer M, Tedford RJ, Doevendans PA, van Veen TA, Tandri H, Wilde AA, Judge DP, van Tintelen JP, Hauer RN, Calkins H. Clinical presentation, long-term follow-up, and outcomes of 1001 arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia/cardiomyopathy patients and family members. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2015;8:437–446. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.114.001003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunn KE, Ashley EA. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy: Toward a modern clinical and genomic understanding. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2015;8:421–424. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lombardi R, da Graca Cabreira-Hansen M, Bell A, Fromm RR, Willerson JT, Marian AJ. Nuclear plakoglobin is essential for differentiation of cardiac progenitor cells to adipocytes in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation research. 2011;109:1342–1353. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.255075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Joe AW, Yi L, Natarajan A, Le Grand F, So L, Wang J, Rudnicki MA, Rossi FM. Muscle injury activates resident fibro/adipogenic progenitors that facilitate myogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:153–163. doi: 10.1038/ncb2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uezumi A, Fukada S, Yamamoto N, Takeda S, Tsuchida K. Mesenchymal progenitors distinct from satellite cells contribute to ectopic fat cell formation in skeletal muscle. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:143–152. doi: 10.1038/ncb2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uezumi A, Ito T, Morikawa D, Shimizu N, Yoneda T, Segawa M, Yamaguchi M, Ogawa R, Matev MM, Miyagoe-Suzuki Y, Takeda S, Tsujikawa K, Tsuchida K, Yamamoto H, Fukada S. Fibrosis and adipogenesis originate from a common mesenchymal progenitor in skeletal muscle. Journal of cell science. 2011;124:3654–3664. doi: 10.1242/jcs.086629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heredia JE, Mukundan L, Chen FM, Mueller AA, Deo RC, Locksley RM, Rando TA, Chawla A. Type 2 innate signals stimulate fibro/adipogenic progenitors to facilitate muscle regeneration. Cell. 2013;153:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O’Connell TD, Rodrigo MC, Simpson PC. Isolation and culture of adult mouse cardiac myocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;357:271–296. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-214-9:271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gao S, Wassler M, Zhang L, Li Y, Wang J, Zhang Y, Shelat H, Williams J, Geng YJ. Microrna-133a regulates insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor expression and vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in murine atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2014;232:171–179. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haudek SB, Xia Y, Huebener P, Lee JM, Carlson S, Crawford JR, Pilling D, Gomer RH, Trial J, Frangogiannis NG, Entman ML. Bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursors mediate ischemic cardiomyopathy in mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:18284–18289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608799103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen SN, Gurha P, Lombardi R, Ruggiero A, Willerson JT, Marian AJ. The hippo pathway is activated and is a causal mechanism for adipogenesis in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Circulation research. 2014;114:454–468. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen SN, Czernuszewicz G, Tan Y, Lombardi R, Jin J, Willerson JT, Marian AJ. Human molecular genetic and functional studies identify trim63, encoding muscle ring finger protein 1, as a novel gene for human hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation research. 2012;111:907–919. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.270207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ruggiero A, Chen SN, Lombardi R, Rodriguez G, Marian AJ. Pathogenesis of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by myozenin 2 mutations is independent of calcineurin activity. Cardiovascular research. 2013;97:44–54. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Gras E, Lombardi R, Giocondo MJ, Willerson JT, Schneider MD, Khoury DS, Marian AJ. Suppression of canonical wnt/beta-catenin signaling by nuclear plakoglobin recapitulates phenotype of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2006;116:2012–2021. doi: 10.1172/JCI27751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamilton TG, Klinghoffer RA, Corrin PD, Soriano P. Evolutionary divergence of platelet-derived growth factor alpha receptor signaling mechanisms. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:4013–4025. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.11.4013-4025.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, Costantini F. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of eyfp and ecfp into the rosa26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vasioukhin V, Bowers E, Bauer C, Degenstein L, Fuchs E. Desmoplakin is essential in epidermal sheet formation. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:1076–1085. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agah R, Frenkel PA, French BA, Michael LH, Overbeek PA, Schneider MD. Gene recombination in postmitotic cells. Targeted expression of cre recombinase provokes cardiac-restricted, site-specific rearrangement in adult ventricular muscle in vivo. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1997;100:169–179. doi: 10.1172/JCI119509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lombardi R, Dong J, Rodriguez G, Bell A, Leung TK, Schwartz RJ, Willerson JT, Brugada R, Marian AJ. Genetic fate mapping identifies second heart field progenitor cells as a source of adipocytes in arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. Circulation research. 2009;104:1076–1084. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.196899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen EY, DeRan MT, Ignatius MS, Grandinetti KB, Clagg R, McCarthy KM, Lobbardi RM, Brockmann J, Keller C, Wu X, Langenau DM. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitors induce the canonical wnt/beta-catenin pathway to suppress growth and self-renewal in embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:5349–5354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1317731111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Polychronopoulos P, Magiatis P, Skaltsounis AL, Myrianthopoulos V, Mikros E, Tarricone A, Musacchio A, Roe SM, Pearl L, Leost M, Greengard P, Meijer L. Structural basis for the synthesis of indirubins as potent and selective inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3 and cyclin-dependent kinases. J Med Chem. 2004;47:935–946. doi: 10.1021/jm031016d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arrighi N, Moratal C, Clement N, Giorgetti-Peraldi S, Peraldi P, Loubat A, Kurzenne JY, Dani C, Chopard A, Dechesne CA. Characterization of adipocytes derived from fibro/adipogenic progenitors resident in human skeletal muscle. Cell Death Dis. 2015;6:e1733. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anam K, Davis TA. Comparative analysis of gene transcripts for cell signaling receptors in bone marrow-derived hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell and mesenchymal stromal cell populations. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2013;4:112. doi: 10.1186/scrt323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rampazzo A, Nava A, Malacrida S, Beffagna G, Bauce B, Rossi V, Zimbello R, Simionati B, Basso C, Thiene G, Towbin JA, Danieli GA. Mutation in human desmoplakin domain binding to plakoglobin causes a dominant form of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. American journal of human genetics. 2002;71:1200–1206. doi: 10.1086/344208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore-Morris T, Guimaraes-Camboa N, Banerjee I, Zambon AC, Kisseleva T, Velayoudon A, Stallcup WB, Gu Y, Dalton ND, Cedenilla M, Gomez-Amaro R, Zhou B, Brenner DA, Peterson KL, Chen J, Evans SM. Resident fibroblast lineages mediate pressure overload-induced cardiac fibrosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:2921–2934. doi: 10.1172/JCI74783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moore-Morris T, Tallquist MD, Evans SM. Sorting out where fibroblasts come from. Circulation research. 2014;115:602–604. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.304854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali SR, Ranjbarvaziri S, Talkhabi M, Zhao P, Subat A, Hojjat A, Kamran P, Muller AM, Volz KS, Tang Z, Red-Horse K, Ardehali R. Developmental heterogeneity of cardiac fibroblasts does not predict pathological proliferation and activation. Circulation research. 2014;115:625–635. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Travers JG, Kamal FA, Robbins J, Yutzey KE, Blaxall BC. Cardiac fibrosis: The fibroblast awakens. Circulation research. 2016;118:1021–1040. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.306565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marian AJ. Modeling human disease phenotype in model organisms: “It’s only a model!”. Circulation research. 2011;109:356–359. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.249409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Libby P. Murine “model” monotheism: An iconoclast at the altar of mouse. Circulation research. 2015;117:921–925. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McAnally AA, Yampolsky LY. Widespread transcriptional autosomal dosage compensation in drosophila correlates with gene expression level. Genome Biol Evol. 2010;2:44–52. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evp054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.