Abstract

Objective

Homophobic victimization, and specifically name-calling, has been associated with greater psychological distress and alcohol use in adolescents. This longitudinal study examines whether sexual orientation moderates these associations, and also differentiates between the effects of name-calling from friends and non-friends.

Method

Results are based on 1,325 students from three Midwestern high schools who completed in-school surveys in 2012 and 2013. Linear regression analysis was used to examine the associations among homophobic name-calling victimization and changes in anxiety symptoms, depressive symptoms, and alcohol use one year later, controlling for other forms of victimization and demographics.

Results

Homophobic name-calling victimization by friends was not associated with changes in psychological distress or alcohol use among either students who self-identified as heterosexual or those who self-identified as lesbian, gay or bisexual (LGB). In contrast, homophobic name-calling by non-friends was associated with increased psychological distress over a one-year period among LGB students, and increased drinking among heterosexual students.

Discussion

Homophobic name-calling victimization, specifically from non-friends, can adversely affect adolescent well-being over time and thus is important to address in school-based bullying prevention programs. School staff and parents should be aware that both LGB and heterosexual adolescents are targets of homophobic name-calling, but may tend to react to this type of victimization in different ways. Further research is needed to understand the mechanisms through which homophobic victimization increases the risk of psychological distress and alcohol use over time.

Longitudinal Associations of Homophobic Name-Calling Victimization With Psychological Distress and Alcohol Use During Adolescence

The use of homophobic epithets at school is commonplace among adolescents. National data indicate that nearly two-thirds of sexual minority (e.g., lesbian, gay, or bisexual; LGB) students report hearing students make derogatory remarks such as “dyke” or “faggot” often or frequently in school (1). Although LGB youth are more likely to experience homophobic name-calling than their heterosexual peers (2, 3), it can be directed towards youth of any sexual orientation. Homophobic name-calling often goes unchecked by school staff for a variety of reasons (1), yet there is growing evidence that homophobic name-calling can have serious deleterious effects on its victims. Understanding the ways in which homophobic name-calling adversely affects adolescent well-being over time, and the conditions under which it is most likely to have an impact, is important for addressing this important and pervasive problem.

Minority stress theory posits that individuals from stigmatized social categories are exposed to excess stress as a result of their marginalized social (often a minority) position, and that this stress increases their likelihood of mental health problems (4). It is often used to explain the relatively high rates of psychological distress and substance use found in studies of sexual minorities (5, 6). Being called homophobic epithets may reinforce this marginalized status among LGB youth, and induce something akin to “minority stress” among heterosexual youth as a result of others conferring a marginalized minority identity on them. Homophobic name-calling victimization might be expected to lead to increased psychological distress and heavier substance use for both LGB and heterosexual youth at least in part through its association with social marginalization.

Cross-sectional and longitudinal research indicates that students with diverse sexual orientations fare poorly from homophobic name-calling victimization. Specifically, LGB students targeted with these epithets and other forms of homophobic victimization experience greater psychological distress (e.g., 7) and are at increased risk for suicidal ideation and attempted suicide (8). Similar associations between homophobic name-calling victimization and psychological distress have been found among middle school and high school students in general (9-11), and one study specifically of heterosexual high school students found that males who experienced homophobic victimization at the beginning of the school year showed increased anxiety and depressive symptoms by the end of the school year (12). Although victimization by peers in general tends to have a greater impact on psychological distress for LGB than heterosexual youth (13), the limited research examining whether this is the case for homophobic name-calling victimization in particular has yielded mixed results. Of two cross-sectional studies, one of high school students from a Midwestern U.S. public school district found a stronger association with psychological distress for LGB youth (14), whereas another study of youth ages 11-17 in Amsterdam did not (3). Longitudinal studies examining whether sexual orientation moderates the effects of homophobic name-calling victimization on subsequent psychological distress are lacking.

In understanding the effects of homophobic victimization on adolescent well-being, substance use has received less empirical attention than psychological distress. Cross-sectional data indicate that adolescents who experience homophobic victimization tend to engage in more alcohol use than those not experiencing this type of victimization (9, 15), with some evidence that this association may be stronger for LGB youth (2, 10, 14). However, longitudinal studies such as the present one are needed to examine whether homophobic victimization during adolescence is a risk factor for escalated substance use over time. This study focuses specifically on alcohol use given the pervasiveness of this behavior among high school students (16) and the importance of understanding risk factors for underage drinking.

There may also be certain social conditions which affect the extent to which being called these epithets is perceived as threatening. One potentially important factor that has received little empirical attention is whether the name-calling is by a friend or non-friend, which may influence how this behavior is perceived and reacted to by the target of the epithet. Adolescents often engage in bullying behaviors such as homophobic name-calling in an attempt to establish dominance over other youth (17) and, as such, it may be stressful to some extent for the victim regardless of its source. However, compared to homophobic name-calling from non-friends, it may be the case that name-calling from friends feels more threatening because adolescents spend more time with these peers and share more intimate emotional connections, and therefore have more to lose from any adverse social effects of the name-calling. However, another possibility is that homophobic name-calling from friends may feel less threatening because the adolescent is still part of a friendship network and reaping the benefits that this status affords, or because the name-calling is being delivered with a less aggressive or marginalizing intention. A better understanding is needed of the extent to which homophobic name-calling from friends and from non-friends have adverse effects on adolescent psychological distress and alcohol use over time.

This study furthers research on the effects of homophobic name-calling victimization on adolescent well-being in several important respects. First, it extends existing cross-sectional research by examining how victimization experiences predict changes in psychological distress and alcohol use over a one-year period. Second, it investigates whether the associations of homophobic name-calling victimization with psychological distress and alcohol use vary depending on the victim's sexual orientation and the nature of the victim-perpetrator relationship (friend vs. non-friend). We hypothesized that positive associations would be found for both sexual minority and heterosexual youth, but would be stronger for sexual minority youth. We did not have an a priori expectation for how the effects of name-calling from friends versus non-friends might differ and considered these analyses to be exploratory. Third, this study investigates whether the associations between homophobic name-calling victimization and poorer adolescent outcomes can be accounted for by other forms of peer victimization. This is an understudied, yet important question given that victimized youth often experience multiple forms of bullying (9). Finally, this study explores whether the frequency of name-calling victimization is positively associated with social marginalization, either perceived (self-ratings of friend support) or actual (number of school-based friendship nominations). If so, we were interested in testing whether social marginalization mediates the associations of homophobic name-calling victimization with psychological distress and alcohol use, as suggested by minority stress theory.

Method

Participants

Students enrolled in three Midwestern public high schools were invited to complete in-school surveys in Spring 2012 (Wave 1) and Spring 2013 (Wave 2) for a study on social networks and adolescent risk behavior. The Wave 1 survey was completed by 2,009 9th-11th grade students; of those who completed Wave 1, 1,420 students (70.68%) also completed the Wave 2 survey. Those who completed Wave 1 only tended to be slightly older (M=15.97, SD=1.01, p<.001), and were more likely to be African American (66.67%) and less likely to be Hispanic (5.13%, p<.001), compared to those who completed both surveys; however, there were not significant group differences on gender or sexual orientation. The analytic sample was restricted to 1,325 students who participated in both waves and were not missing information on key study variables. The analytic sample is 46.1% male and 15.70 years old on average at Wave 1; other demographic characteristics can be found in Table 1. Study materials and procedures, including a waiver of active parental consent (students provided informed assent for their participation), were approved by the institutional review board and school district administrators, and a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics for Main Study Variables at Wave 1 by Sexual Orientation.

| Full Sample | Heterosexual | LGB | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=1325) | (N=1076) | (N=249) | ||

|

|

||||

| Mean (SD)/% | Mean (SD)/% | Mean (SD)/% | pa | |

| Victimization | ||||

| HV Friend (0-4) | 0.81 (1.22) | 0.77 (1.20) | 0.98 (1.29) | * |

| HV Non-friend (0-4) | 0.24 (0.65) | 0.19 (0.57) | 0.45 (0.88) | ‡ |

| AV (0-4) | 0.52 (0.71) | 0.47 (0.65) | 0.73 (0.89) | ‡ |

| Well-Being | ||||

| Anxiety (0-2.5) | 0.55 (0.72) | 0.55 (0.71) | 0.56 (0.72) | |

| Depression (0-2.8) | 0.80 (0.67) | 0.76 (0.64) | 0.97 (0.74) | ‡ |

| Alcohol use (0-2) | 0.05 (0.20) | 0.04 (0.19) | 0.07 (0.24) | # |

| Marginalization | ||||

| Friend support (0-1.6) | 0.38 (0.49) | 0.38 (0.50) | 0.35 (0.47) | |

| Popularity (0-20) | 3.86 (3.08) | 3.95 (3.16) | 3.43 (2.68) | * |

| Demographics | ||||

| Male | 46.11 | 50.74 | 26.10 | ‡ |

| White | 32.83 | 32.42 | 34.54 | |

| Black | 49.21 | 49.54 | 47.79 | |

| Hispanic | 11.09 | 10.87 | 12.05 | |

| Other race/ethnicity | 6.87 | 7.16 | 5.62 | |

| 9th grade | 34.94 | 34.67 | 36.14 | |

| 10th grade | 37.35 | 36.34 | 37.35 | |

| 11th grade | 26.51 | 29.00 | 26.51 | |

Note.

Comparison of heterosexual and LGB students.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001. HV = homophobic victimization; AV = aggression victimization.

Measures

Demographics

Gender, race/ethnicity, and school grade were included as covariates in the analyses. Sexual orientation was assessed by asking students how they would identify their sexual orientation given the following options: exclusively heterosexual; predominantly heterosexual; bisexual, but more heterosexual; bisexual; bisexual, but more lesbian or gay; predominantly lesbian or gay; and exclusively lesbian or gay. We then classified students as either heterosexual (i.e., endorsed “exclusively heterosexual”) or LGB (i.e., endorsed any other option). Transgender was not a response option for this item. Demographic information generally came from the Wave 1 survey; in cases where an item was missing, we used Wave 2 information instead.

Past month victimization (Wave 1)

Homophobic name-calling victimization was assessed with three items from the target scale of the Homophobic Content Agent Target Scale (HCAT; 18). Students were asked the following: “Some kids call each other names such as homo, gay, lesbo, or fag. How many times in the last 30 days did the following people say these words to you?” They then rated how often they experienced this name-calling from a friend, someone that they did not like, and someone that they did not know well (0=never, 1=1 or 2 times, 2=3 or 4 times, 3=5 or 6 times, 4=7 or more times). Frequency of homophobic name-calling from someone they did not like and someone they did not know well were highly correlated (r=0.71) and thus were averaged. Physical and verbal aggression victimization was assessed at Wave 1 using the four-item University of Illinois Victimization Scale (UIVS; 19). Students rated how often things happened to them in the past 30 days such as “Other students called me names”, “Other students made fun of me”, “Other students picked on me”, and “I got hit and pushed by other students” (0=never to 5=7 or more times; α=0.71).

Past month psychological distress (Waves 1-2)

Anxiety symptoms in the past 30 days were assessed by averaging ratings of two items created for this study asking how often they worried a lot and were nervous or afraid (r=0.60). Depressive symptoms in the past 30 days were assessed by averaging ratings on the 5-item Modified Depression Scale (20) which asked how often they were very sad, were grouchy or irritable, felt hopeless about the future, slept a lot more or less than usual, and had difficulty concentrating on schoolwork (α=0.78). All of these items were rated on a scale from 0=never to 4=almost always.

Past month alcohol use (Waves 1-2)

Average number of drinks per day in the past 30 days was assessed with two items. The first item asked how often they had at least one full drink of alcohol (0 days, 1 day, 2 days, 3-5 days, 6-9 days, 10-19 days, 20-30 days) and this value was converted through linear interpolation into a point estimate of the number of days they drank (0, 1, 2, 4, 7.5, 14.5, 25). The second item asked the number of drinks consumed on the days they drank (a few sips, about ½ a drink, 1 drink, 2 drinks, 3 or more drinks) and this value was converted into an estimated of the number of drinks (0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 3). Average number of drinks per day was calculated as: [(number of days × number of drinks)/30].

Social marginalization (Wave 1)

We used two indicators of marginalization, with lower scores indicating greater marginalization: friend social support and school-based friendship nominations. Social support was assessed with the Vaux Social Support Record peer subscale, which is an adaptation of Vaux's Social Support Appraisals scale (21). Students rated how much they agreed with each statement: they have friends who care about their feelings and what happens to them, give good suggestions and advice about their problems, and help them with practical problems (0=not at all to 2=a lot; α=0.92). School-based friendship nominations involved asking students to “Tell us who your friends are. Who do you hang out with the most at school?” They could list up to 8 friends and were asked to not list their siblings or friends that did not go to their school. The total number of nominations received by each student was summed, with this indicator corresponding to the “indegree centrality” network measure that assesses popularity as measured by direct friend linkages with others (22).

Analytic Plan

Generalized linear models were used to examine associations of homophobic name-calling victimization with adolescent psychological distress and alcohol use. Victimization from friends and victimization from non-friends were correlated at r=0.32, p<.01 and included in the same model. We first examined these associations controlling for aggression victimization, sexual orientation, the Wave 1 version of the outcome variable, gender, race/ethnicity, and school grade. We then added three interaction terms to these models: homophobic victimization from friends by sexual orientation, homophobic victimization from non-friends by sexual orientation, and aggression victimization by sexual orientation. These analyses were clustered within school. Bivariate correlations were used to explore whether frequency of name-calling victimization was positively associated with social marginalization as a first step in determining whether to test for mediation.

Results

Table 1 compares heterosexual and LGB students on baseline rates of victimization, psychological distress, alcohol use, social marginalization, and demographic characteristics. Results indicate that LGB students reported significantly more homophobic victimization (from both friends and non-friends) and aggression victimization. On average, LGB students reported significantly more depressive symptoms and a significantly lower peer-nominated popularity than heterosexual students, as well as marginally higher alcohol use (p=.10). LGB and heterosexual students did not differ significantly on anxiety symptoms or friend support. Although LGB students were less likely to be male than heterosexual students, these groups did not differ on other demographic characteristics. Correlations among these variables can be found in a supplemental table.

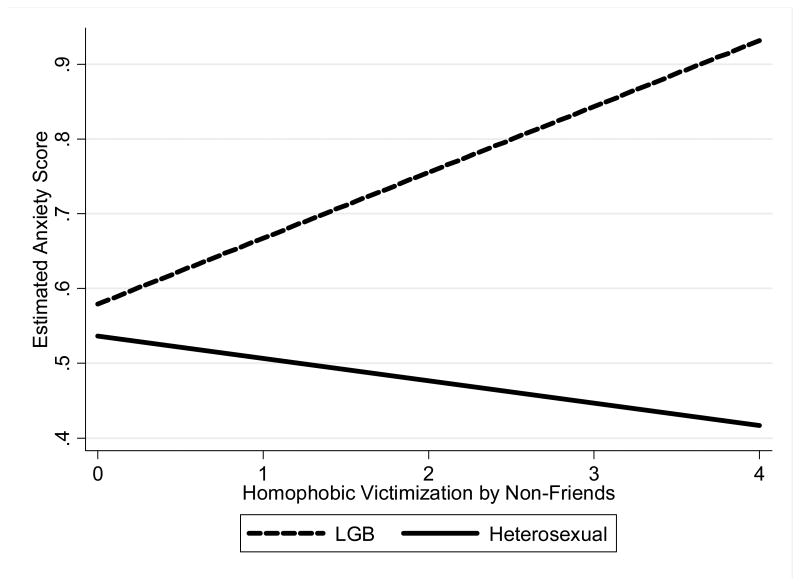

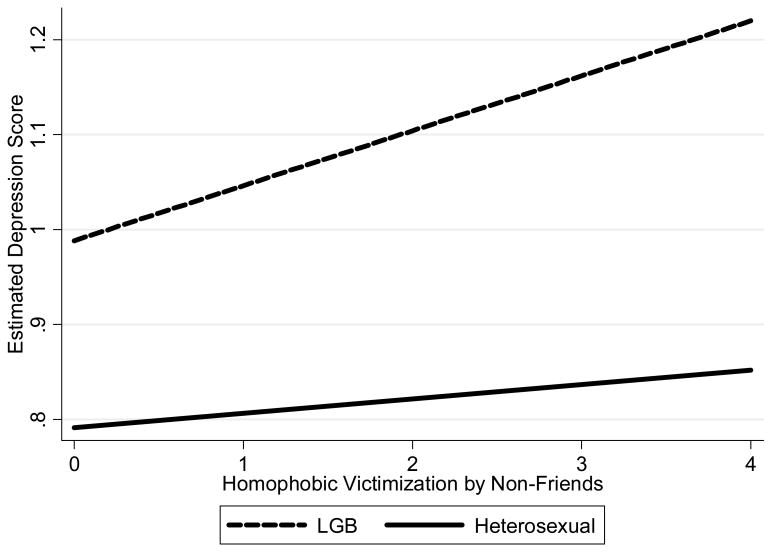

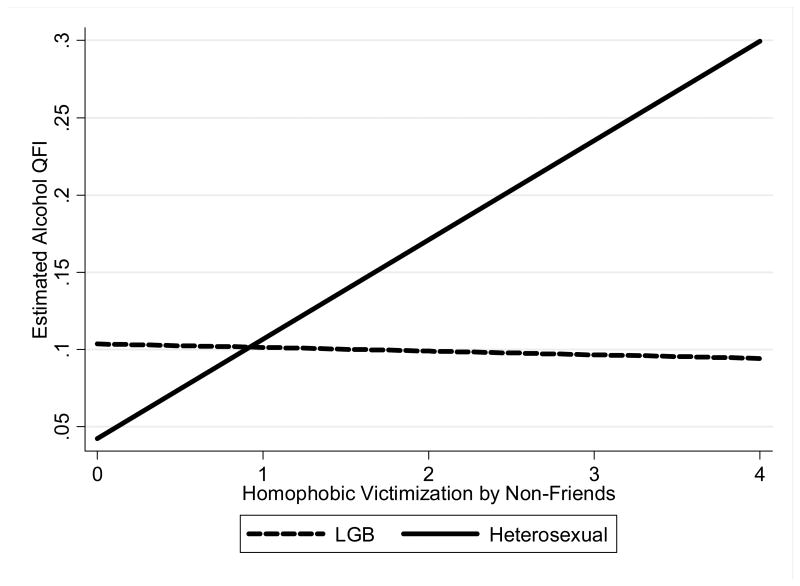

Table 2 presents estimates from linear models predicting changes in psychological distress and alcohol use over a one-year period associated with initial homophobic name-calling victimization, controlling for aggression victimization and demographic characteristics. Homophobic name-calling from friends was not associated with changes in either measure of psychological distress or alcohol use. However, homophobic name-calling victimization from non-friends interacted with sexual orientation in predicting changes in psychological distress and alcohol use over time. In the case of anxiety symptoms, heterosexual and LGB students had similar levels of anxiety symptoms in the absence of homophobic name-calling from non-friends; however, as the frequency of name-calling from non-friends increased, LGB students showed a pronounced increase in their anxiety symptoms over time (see Figure 1a). There was also a marginally significant (p<.10) interaction of homophobic name-calling from non-friends and sexual orientation on depressive symptoms, which showed a more pronounced increase in depressive symptoms for LGB compared to heterosexual students as homophobic name-calling increased (see Figure 1b). In the case of alcohol use, heterosexual students tended to drink less than their LGB peers in the absence of homophobic name-calling from non-friends, but surpassed LGB students in alcohol use as the name-calling from non-friends became more frequent (see Figure 1c).

Table 2. Clustered Linear Regression Models Predicting Change in Alcohol Use, Anxiety, and Depression from Homophobic Name-Calling Victimization.

| Anxiety Symptoms | Depressive Symptoms | Alcohol Use | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|

|

||||||

| Variable | b | b | b | b | b | b |

| Outcome variable (W1) | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.49 * | 0.49 * |

| Male | -0.19 * | -0.18 † | -0.10 * | -0.10 * | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Black | -0.12 | -0.12 | -0.03 | -0.02 | -0.04 | -0.04 |

| Hispanic | -0.02 | -0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | -0.06 * | -0.06 * |

| Other race | 0.03 | 0.02 | -0.07 * | -0.07 * | -0.04 # | -0.04 # |

| Grade | -0.02 | -0.03 | -0.02 | -0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Heterosexual | -0.03 | 0.00 | -0.14 | -0.23 | -0.01 | -0.01 |

| HV-F | 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| HV-NF | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.02 | -0.03 |

| AV | 0.03 | -0.01 | 0.05 # | -0.05 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| HV-F × Heterosexual | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.01 | |||

| HV-NF × Heterosexual | -0.13 * | -0.11 # | 0.08 * | |||

| AV × Heterosexual | 0.06 | 0.15 | -0.04 | |||

Note.

p < .10.

p < .05.

p < .01. Reference group for race/ethnicity is non-Hispanic White.

HV-F = homophobic victimization by friends; HV-NF = homophobic victimization by non-friends; AV = aggression victimization.

Figure 1. Figure 1a, 1b, and 1c.

Interactions of homophobic name-calling victimization from non-friends X sexual orientation on changes in estimated anxiety, depression, and alcohol use scores over one-year period

Finally, we explored whether homophobic name-calling victimization was positively associated with the two indicators of social marginalization. Non-significant correlations were found between perceived friend support and homophobic name-calling from friends (r=0.02, p=.52) and non-friends (r=0.03, p=.25), as well as school-based friendship nominations and homophobic name-calling from non-friends (r=-0.03, p=.30). A significant correlation was found between school-based friendship nominations and name-calling from friends; however, contrary to expectations, it indicated that more popular students tended to be the target of more homophobic name-calling (r=0.21, p<.001). Given the lack of evidence that victimization is associated with greater social marginalization, mediation tests were not needed.

Discussion

Given the pervasiveness of homophobic name-calling during adolescence, it may be easy to dismiss these behaviors and commentary as harmless banter. However, the use of homophobic epithets is strongly associated with bullying behavior (23) and its effects can be far from benign for youth who are on the receiving end. Prior research has shown that being the target of homophobic epithets is associated with higher psychological distress (7-12). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal study to show that high school students who experience more frequent homophobic name-calling victimization show significant increases in their psychological distress (particularly anxiety symptoms) and alcohol use over a one-year period. These associations held even after controlling for whether the student was also experiencing other types of peer victimization at school such as being made fun of, picked on, or hit and pushed. This is important given that bullied students may experience multiple forms of peer victimization (9), and there has been some question in the literature about whether homophobic name-calling has deleterious effects on adolescent well-being in its own right, apart from other forms of victimization the student may be experiencing (3). Our results suggest that this is indeed the case – although the effects of homophobic name-calling victimization depend on the sexual orientation of the victim and his/her relationship to the perpetrator.

In the case of homophobic name-calling from friends, neither LGB nor heterosexual students who experienced more name-calling showed significant changes in their psychological distress or alcohol use over time. This finding was unexpected given that LGB youth appear to be more negatively affected by victimization in general (13), and at least one study found that LGB youth responded more negatively to homophobic name-calling victimization in particular (14). However, results from the present study emphasize the importance of differentiating between homophobic name-calling victimization from friends and non-friends, which previous studies have not done. One possible explanation for the lack of association between homophobic name-calling from friends and decreases in adolescent well-being is that derogatory language within friendship groups may sometimes be used as terms of endearment or camaraderie rather than as a means of marginalizing certain group members. This interpretation is consistent with our unexpected finding of a modest, but significant positive correlation between homophobic name-calling from friends and number of school-based friendship nominations, indicating that those who experienced more name-calling tended to be more popular at school.

In contrast, homophobic name-calling victimization from peers they did not like or did not know well was associated with decreased well-being over time, with the nature of the response differing for heterosexual and LGB adolescents. Our findings suggest that LGB students appeared to feel more personally threatened by this type of victimization. Compared to their heterosexual peers, LGB students showed a greater increase in anxiety symptoms over time, such as worrying a lot and being nervous about the future, and a trend of increased depressive symptoms at higher levels of name-calling victimization. Our finding that homophobic victimization is more strongly associated with anxiety than depressive symptoms is consistent with some prior research (12), and this finding is also consistent with the heightened vigilance due to discrimination posited by the minority stress model (4). A very different pattern was found for alcohol use, which was positively associated with homophobic name-calling from non-friends among heterosexual students only. An important direction for future research is to better understand why homophobic name-calling by non-friends may encourage drinking among heterosexual youth, particularly in the absence of a similar increase in psychological distress. Examining these adolescents’ motivations for drinking (24) may provide useful insights. For example, they may drink due to conformity or social motives – that is, as a means of trying to fit in or improve their social experiences with peers – more than to cope with anxiety and depression as a result of being marginalized (indeed, homophobic name-calling from non-friends was unrelated to our indicators of social marginalization). Drinking motives in this context deserve further empirical attention for at least three reasons. First, it can shed light on the mechanisms through which homophobic name-calling from non-friends influences drinking behavior. Second, certain motives for drinking in late adolescence are more strongly predictive of subsequent alcohol use and symptoms of alcohol use disorder in adulthood (25); as such, some victimized adolescents may be at greater risk for later drinking problems than others and in need of early intervention. Third, the interventions themselves to address alcohol use among victimized adolescents may be more effective to the extent that they are tailored to the adolescent's motives for drinking in response to being victimized (26).

Findings from this study should be interpreted in light of several limitations. Results are based on a cohort of youth recruited from three Midwest public schools and may not generalize to youth in other school environments or parts of the country. Although the longitudinal design is a notable strength of this study, it is a limitation that the follow-up period of one year did not allow us to assess the longer-term effects of homophobic name-calling victimization. Finally, we lacked statistical power to test whether these results differed by gender or sexual minority subgroups; this is an important direction for future research.

Our findings indicate that the consequences of experiencing homophobic name-calling victimization on adolescent well-being are complex. Effective interventions to assist adolescents who have been victimized by homophobic name-calling may need to include content tailored not only to the sexual orientation of the victim, but also the victim's relationship to the perpetrator. Towards this end, qualitative research examining more local peer group norms for homophobic bullying (e.g., peer groups where it is normative versus not) would be useful for better understanding how adolescents interpret and respond to homophobic name-calling in different peer contexts. In addition, future research that provides a deeper and more nuanced understanding of the mechanisms through which homophobic name-calling victimization increases psychological distress and substance use, as well as identifies individual and contextual factors associated with resilience in the face of homophobic name-calling (27), are needed to help inform intervention content to improve outcomes for victimized adolescents.

Supplementary Material

Implications and Contributions.

Homophobic name-calling victimization in high school is associated with an increase in alcohol use and psychological distress over time. However, the sexual orientation of the victim and the victim's relationship to the perpetrator are important factors to consider in efforts to address the adverse effects of this form of victimization.

Acknowledgments

Work on this article was support by grant R01DA033280-01 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (PI: Harold D. Green). This research uses data from grant # 2011-90948-IL-IJ from the National Institute of Justice (PI: Dorothy Espelage).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Kosciw JG, Greytak EA, Palmer NA, et al. The 2013 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender youth in our nation's schools. New York: GLSEN; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birkett M, Espelage DL, Koenig B. LGB and questioning students in schools: The moderating effects of homophobic bullying and school climate on negative outcomes. J Youth Adolescence. 2009;38:989–1000. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9389-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Collier KL, Bos HMW, Sandfort TGM. Homophobic name-calling among secondary school students and its implications for mental health. J Youth Adolescence. 2013;42:363–375. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9823-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129:674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A psychological mediation framework Psychol Bull. 2009;135:707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction. 2008;103:546–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birkett M, Newcomb ME, Mustanski B. Does it get better? A longitudinal analysis of psychological distress and victimization in lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning youth J Adolescent Health. 2015;56:280–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Bergen DD, Bos HM, van Lisdonk J, et al. Victimization and suicidality among Dutch lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:70–72. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Espelage DL, Low S, De La Rue L. Relations between peer victimization subtypes, family violence, and psychological outcomes during early adolescence. Psychol Violence. 2012;2:313–324. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poteat VP, Espelage DL. Predicting psychosocial consequences of homophobic victimization in middle school students. J Early Adolescence. 2007;27:175–191. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swearer SM, Turner RK, Givens JE, et al. “You're so gay”! Do different forms of bullying matter for adolescent males? School Psychol Rev. 2008;37:160–173. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Poteat VP, Scheer JR, DiGiovanni CD, et al. Short-term prospective effects of homophobic victimization on the mental health of heterosexual adolescents. J Youth Adolescence. 2014;43:1240–1251. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-0078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fedewa AL, Ahn S. The effects of bullying and peer victimization on sexual-minority and heterosexual youths: A quantitative meta-analysis of the literature. Journal of GLBT Family Studies. 2011;7:398–418. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Espelage DL, Aragon SR, Birkett M, et al. Homophobic teasing, psychological outcomes, and sexual orientation among high school students: What influence do parents and schools have? School Psychol Rev. 2008;37:202–216. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Darwich L, Hymel S, Waterhouse T. School avoidance and substance use among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and questioning youths: The impact of peer victimization and adult support. J Educ Psychol. 2012;104:381–392. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miech RA, Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, et al. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research. The University of Michigan; 2015. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use, 1975–2014: Volume I, secondary school students. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodkin PC, Espelage DL, Hanish LD. A relational framework for understanding bullying developmental antecedents and outcomes. Am Psychol. 2015;70:311–321. doi: 10.1037/a0038658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Poteat VP, Espelage DL. Exploring the relation between bullying and homophobic verbal content: The Homophobic Content Agent Target (HCAT) scale. Violence and victims. 2005;20:513–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Espelage DL, Holt MK. Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. J Emot Abuse. 2001;2:123–142. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn EC, Johnson RM, Green JG. The Modified Depression Scale (MSD): A brief, no-cost assessment tool to estimate the level of depressive symptoms in students and schools. SchMent Health. 2012;4:34–45. doi: 10.1007/s12310-011-9066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vaux A, Phillips J, Holly L, et al. The Social Support Appraisals (SS-A) Scale: Studies of reliability and validity. Am J Commun Psychol. 1986;14:195–219. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Freeman LC. Centrality in social networks conceptual clarification. Soc Networks. 1979;1:215–239. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poteat VP, Rivers I. The use of homophobic language across bullying roles during adolescence. J Appl Dev Psychol. 2010;31:166–172. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol Assessment. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patrick ME, Schulenberg JE, O'Malley PM, et al. Adolescents' reported reasons for alcohol and marijuana use as predictors of substance use and problems in adulthood. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2011;72:106–116. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canale N, Vieno A, Santinello M, et al. The efficacy of computerized alcohol intervention tailored to drinking motives among college students: A quasi-experimental pilot study. Am J Drug Alcohol Ab. 2015;41:183–187. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2014.991022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sapouna M, Wolke D. Resilience to bullying victimization: The role of individual, family and peer characteristics. Child Abuse Neglect. 2013;37:997–1006. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.