INTRODUCTION

The branchial cyst, fistula, and sinuses are the anomalies of the branchial apparatus which consists of five mesodermal arches separated by invaginations of the ectoderm called as clefts. The branchial fistula is not a true fistula as it rarely has two openings. More often even if both ends are patent there is a thin membrane covering the internal opening.1 Demonstration of a complete branchial fistula on imaging studies is uncommon.2 We present a case of a complete branchial fistula in a young lady with a special emphasis on imaging.

CASE REPORT

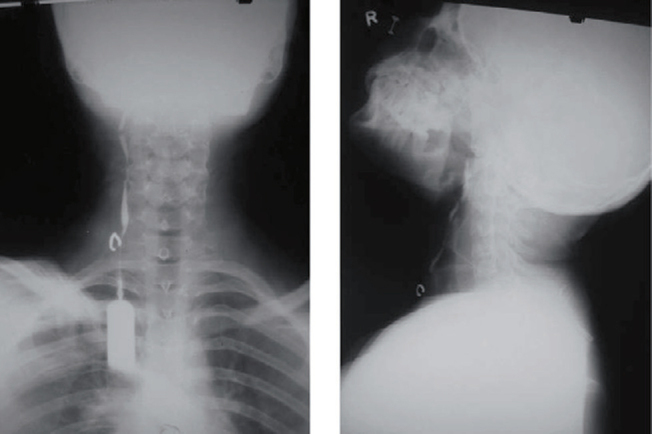

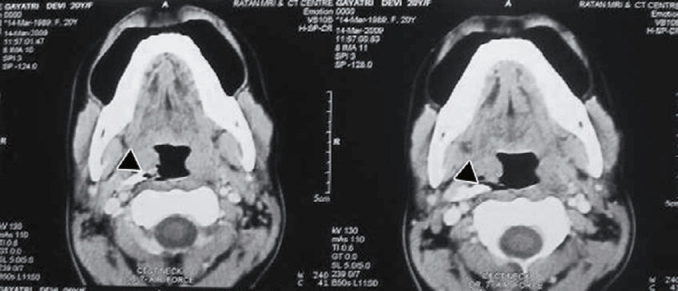

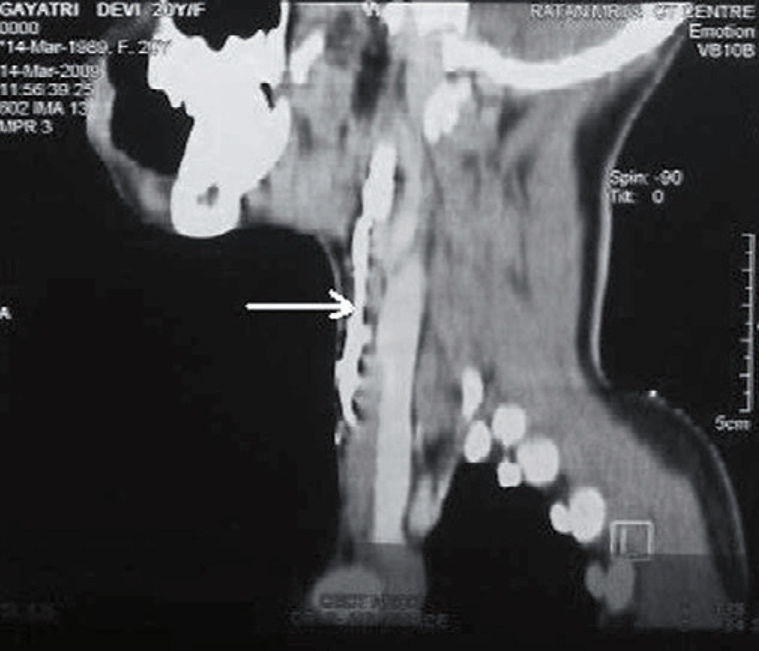

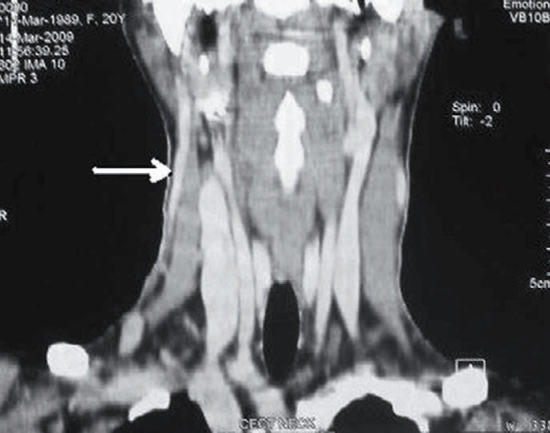

A 26-year-old lady presented with history of discharge from the right-hand side of neck on and off since birth. There was no history of trauma or operative intervention. Local examination revealed a pinhead opening along the anterior border of sternocle domastoid on the right-hand side of lower third of neck. There was no sign of inflammation around the opening. A sinogram study using iodinated contrast media revealed a tract coursing cranially up to the right tonsillar fossa. There was no spillage of contrast at the cranial end (Figure 1). A contrast enhanced CT sinogram was done to delineate the exact course of tract before surgery. It revealed a contrast delineated tract coursing anterior to the right sternocleidomastoid muscle, between internal and external carotid arteries and finally ending at the right tonsillar fossa (Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4). Based on imaging and the clinical history a diagnosis of branchial fistula of second branchial arch was made. The patient underwent excision of the tract by a step ladder approach (Figure 5).

Figure 1.

Sinogram anteroposterior and lateral view demonstrating the sinus tract.

Figure 2.

Axial CECT scan of neck showing the contrast delineated sinus tract (black arrowhead) on the right-hand side.

Figure 3.

Sagittal reformat CT image of sinus tract (white arrow).

Figure 4.

Coronal reformat CT image of the sinus tract (white arrow).

Figure 5.

Peroperative specimen of sinus tract.

DISCUSSION

The branchial apparatus were first described by Von Baer while its anomalies were first described by von Ascheroni.3 The branchial fistula is an uncommon anomaly of embryonic development of branchial apparatus. Amongst these, anomalies of second branchial arch as well as pouch are common. They represent 90–95% of branchial anomalies.4 During embryonic development, the second arch grows caudally and it covers the second, third, and fourth branchial clefts. The cervical sinus of His is formed by the fusion of this second arch with the enlarging epipericardial ridge of the fifth arch. The edges of cervical sinus in the due course fuse and hence in life no defect is seen. However, it is the persistence of intervening ectoderm that gives rise to branchial cyst. The branchial fistula results from breakdown of the endoderm, usually in the second pouch. In the normal course a persistent fistula of the second branchial cleft and pouch passes from the external opening in the mid or lower third of neck in the line of the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, deep to platysma along the carotid sheath. The tract then passes medially deep between the internal and external carotid arteries, as in our case, after crossing over the glossopharyngeal and hypoglossal nerves. Finally, it opens internally in the tonsillar fossa.

Clinically most of these cases present with mucoid discharge from the anterior aspect of neck. In addition presence of infection may lead to formation of an abscess and signs of inflammation at the site of opening. Although branchial fistula may occur at any age but commonly they present in first or second decade of life.5 Most of the times it is a simple sinus opening that extend up the neck for a variable distance. Complete branchial fistula with internal opening into tonsillar region is rare. Besides radiological demonstration of complete tract is further difficult. Ford et al4 documented one case in their series of 98 fistulae in which the entire tract was visualized.

Bailey classified the second branchial cleft anomalies into four subtypes based on their location.6 Types I—III are the most frequently occurring second arch anomalies, with type II being the most common.

-

•

Type I—It lies deep to the platysma muscle and the overlying cervical fascia, anterior to sternocleidomastoid muscle.

-

•

Type II— It is thought to be due to persistence of sinus of His. These lie in contact with the great vessels. It is located posterior to submandibular gland, anterior and medial to sternocleidomastoid muscle.

-

•

Type III– The tract courses between internal and external carotid arteries and may extend to lateral wall of pharynx or skull base. These are thought to arise from the dilated pharyngeal pouch.

-

•

Type IV– It arises from remnant of pharyngeal pouch and lie next to the pharyngeal wall, medial to the great vessels at the level of the tonsillar fossa.

The diagnosis is most often clinical and radiological investigations are rarely asked for. However, a fistulogram if performed delineates the tract and it is often the commonest investigation available as done in our case. A complete fistula demonstrable by a fistulogram is uncommon.2 With the available of multislice computed tomography scan a CT fistulogram with reformatted images unambiguously delineates the relation of sinus tract to that of important structures of neck. It also helps in classifying the type of lesion, provides a roadmap for surgeon prior to surgery, and reduces the chance of recurrence.

MRI is most advantageous for Type I first branchial cleft cysts and for parapharyngeal masses that may be second branchial cleft cysts. By the inherent nature of better tissue contrast it provides the relationship of glandular tissue to the mass (e.g. fat planes between the parotid gland and a parapharyngeal mass) and hence acts as a roadmap prior to surgery.

Ultrasound is useful in situations where CT scanning and MRI are unavailable. Ultrasound can delineate the branchial cleft cyst. However, complete delineation of fistulous tract is difficult even with the use of high resolution transducers. The uncomplicated branchial cleft cyst appears with anechoic contents. The presence of faint echogenic debris in the cyst arises from the cellular material, cholesterol crystals, and keratin within the cyst. Presence of pseudosolid or heterogeneous mass with internal debris and septa should make the radiologist to consider other differential diagnoses like tuberculous node, noninflammatory lesions such as malignant lymphadenopathy, lipoma, nerve sheath tumour, carotid body tumour, external laryngocoele, and cystic hygroma. Although ultrasound can confirm the cystic nature of a mass, it does not adequately evaluate the extent and depth of neck lesions.7

The treatment of choice for branchial fistula is surgical excision. Several surgical approaches have been described for the management of a branchial fistula. These include a transcervical approach, either by a stepladder approach or through a long incision along the anterior border of sternocliedomastoid and a combined pull through technique. The standard surgery for a second branchial arch fistula is the stepladder approach originally described by Bailey in 1933 with two incisions in the neck that gives exposure of the fistula tract with less tissue dissection. The higher incision should be bigger than the lower one because the fistula tract is deeper in location in the vicinity of important neurovascular structures. The reported incidence of recurrence rate was 3% where only external approach was used. This most probably is due to incomplete excision of the fistula tract in the parapharyngeal space.4 However, no recurrence rate is reported after using combined oral and transcervical approach.

In conclusion, a complete branchial fistula demonstrable on imaging studies is uncommon. Imaging studies in the form of a fistulogram and a CT fistulogram confirm the diagnosis, define the extent of the tract, and delineate the relation of sinus tract to that of important structures of neck which facilitates its complete excision thereby reducing recurrence rates.

REFERENCES

- 1.Shekhar C, Kumar R, Kumar R, Mishra SK, Roy M, Bhavana K. The complete branchial fistula: a case report. Ind J Otolaryngol Head Neck Sur. 2005;57:320. doi: 10.1007/BF02907698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Augustine AJ, Pai KR, Govindarajan R. Clinics in diagnostic imaging. Sing Med J. 2001;42:494–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De PR, Mikhail T. A combined approach excision of branchial fistula. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109:999–1000. doi: 10.1017/s002221510013186x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford GR, Balakrishnan A, Evans JN. Branchial cleft and pouch anomalies. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106:137–143. doi: 10.1017/s0022215100118900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ang AH, Pang KP, Tan LK. Complete branchial fistula. Case report and review of the literature. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:1077–1079. doi: 10.1177/000348940111001116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey H. Branchial Cysts and Other Essays on Surgical Subjects in the Faciocervical Region. Lewis; London: 1929. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ahuja A, King AD, Metriweli C. Second branchial cleft cyst: variability of sonographic appearances in adult cases. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:315–319. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]