Introduction

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma (CTCL) is a subset of non-Hodgkin's T-cell lymphomas which presents with malignant lymphocytic infiltration of the skin. The disease spectrum is characterized by clonal proliferation of helper T-cells of the CD4 phenotype in the skin. Mycosis Fungoides (MF), the commonest variant of CTCL, is characterized clinically by an indolent clinical course with subsequent evolution of patches, plaques andtumours and histologically by the infiltration of the epidermis by medium-sized to large atypical T-cells with cerebriform nuclei [1]. Although not very rare worldwide, it is commonest among Africans and relatively uncommon among Asians. Hypopigmented MF is a rare variant of patch stage MF in the dark skinned. Folliculotropic MF is an uncommon variant characterized by folliculotropic T-cell infiltrates with or without mucinous degeneration of the hair follicles.

Case Report

Case 1

A 43 year old male presented with insidious, dark, raised, painless lesions over his face for four years. There was no history of fever, weight loss, epistaxis, red eyes, testicular pain, swelling of hands/feet, muscle weakness, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, joint pains or systemic symptoms.

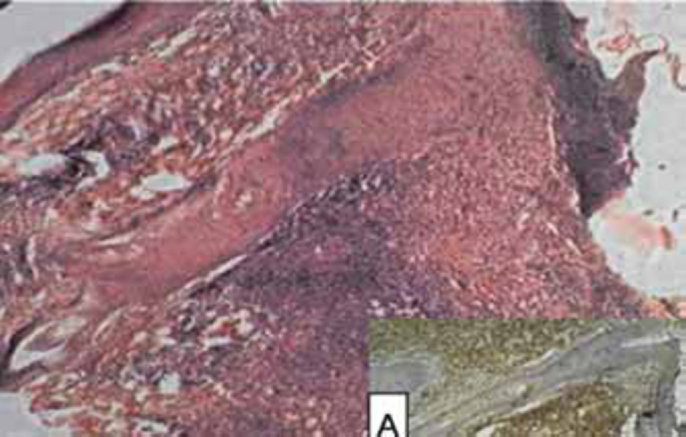

General physical and systemic examination was normal. Dermatological examination revealed two discrete, well defined, dusky-erythematous, boggy, alopecic plaques studded with follicular papules over the left eyebrow and chin (Fig. 1A). He had a solitary, non-tender left preauricular lymph node. Haematological and biochemical investigations were normal. No atypical cells were noticed in the peripheral blood smear. Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) of preauricular lymph node revealed polymorphic inflammatory cells with no granulomas or atypical cells. Mantoux test, anti nuclear antibody (ANA) screen, ultrasonography (USG) abdomen and chest radiograph were normal. Skin biopsy revealed dermal perifollicular infiltrates of atypical hyperchromatic T cells, blast cells and admixed histiocytes and eosinophils, with marked folliculotropism and follicular mucin deposits on Alcian blue staining (Fig. 2). Immunophenotypical analysis demonstrated a CD3+CD4+CD8-phenotype of the neoplastic T cells (Fig. 2, Inset A). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) over deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) extracted from the skin revealed T-cell monoclonality. Based on the clinical, histopathological and immunophenotypical findings, a diagnosis of Folliculotropic MF (Stage II A) (T1N1M0B0) was made [2].

Fig. 1.

Folliculotropic Mycosis Fungoides (A: Before treatment; B: After six months of treatment)

Fig. 2.

(H&E, X150) Photomicrograph showing marked follicular exocytosis; with strong CD 3 positivity (Inset ‘A’)

Case 2

A 17 year old male developed gradually progressive, dark and light coloured, non itchy, painless, scaly patches over the thighs and trunk for 15 years. There was no history of numbness, epistaxis, red eyes, testicular pain, swelling of hands/feet, muscle weakness, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, joint pain, weight loss, fever, breathlessness, chest pain, cough and palpitation.

General and systemic examination was normal. Dermatological examination revealed discrete, ill-defined, hyperpigmented, scaly plaques over medial aspect of right thigh and the left anterior chest wall. There were multiple, ill defined, normesthetic, hypopigmented, polysized macules over the trunk involving > 10% body surface area (BSA) (Fig. 3 A).

Fig. 3.

Hypopigmented Mycosis Fungoides (A: Before treatment; B: After six months of treatment)

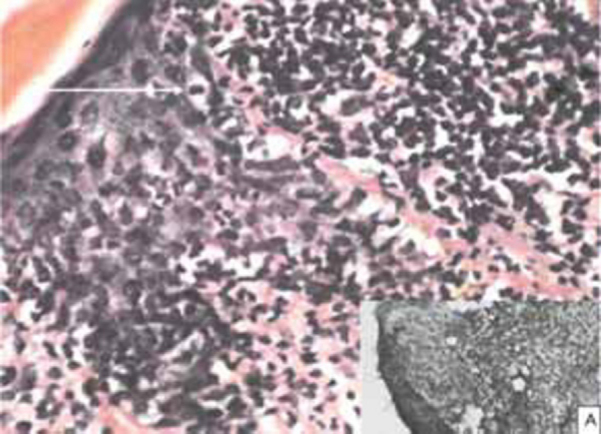

Biochemical and haematological investigations were normal. No atypical cells were noticed in the peripheral blood smear. USG abdomen and chest skiagram were normal. Skin biopsy from the hypopigmented patch revealed perivascular and diffuse dermal infiltrates with variable infiltration of the epidermis by medium-sized and large atypical T-cells with cerebriform nuclei, admixed small lymphocytes, histiocytes andeosinophils (Fig. 4). Pautrier microabscesses were absent. Immunophenotypical analysis demonstrated a CD3+CD4+CD8- phenotype of the neoplastic T cells (Fig 4 A). Based on the clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical findings, a diagnosis of Hypopigmented MF (Stage IB) (T2N0M0B0) was made [2].

Fig. 4.

(H&E, X400) Photomicrograph showing marked exocytosis by pleomorphic neoplastic lymphocytes (white arrow); with strong CD 3 positivity (Inset ‘A’)

Psoralen + Ultra Violet-A (PUVA) was administered to both the cases (8-Methoxypsoralen @ 0.6 mg/kg BW, followed two hours later by exposure to UV-A in PUVA chamber, gradually increasing dosage from 2.5J/m2 twice weekly). In Case-1, only head and neck areas were exposed taking due precautions with whole body clothing and UV protective goggles. As he responded poorly to 25 cycles of PUVA, topical 5% imiquimod cream overnight application twice weekly was added. Within three months, the preauricular lymph node disappeared completely and lesions regressed with residual alopecia (Fig. 1B). Case-2 showed remarkable response in six months to whole body PUVA therapy alone, with the hypopigmented macules merging almost imperceptibly with surrounding normal skin (Fig. 3B). No other skin directed therapy or topical agents were offered. None of them developed adverse drug reactions and both are under regular follow-up. It is planned to continue PUVA till clearance/remission is achieved, followed by maintenance schedule.

Discussion

Primary CTCLs have been classified by the European Organization for Research on the Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) and World Health Organisation (WHO) based on cell type (T cell, NK cell, B cell or precursor cell) and clinical outcome (indolent or aggressive) [3].

Folliculotropic MF has distinctive clinical and histologic features, is more refractory to standard treatment and has a worse prognosisthan classical MF. First described in 1957 as ‘Alopecia Mucinosa’, and later as ‘Follicular Mucinosis’, two types are reported: one occurring in children and young adults without other cutaneous or extracutaneous association (Idiopathic), the other occurring in elderly patients and associated with MF or Sézary syndrome (Lymphoma-associated) [4, 5]. Progression of Idiopathic Follicular Mucinosis into CTCL has been reported [6].

In our first case, clinical differentials of rosacea, sarcoidosis and tumid discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE) were considered, but histopathology and phenotyping ruled them out. It has been suggested that all pilotropic forms of MF should be included under the term ‘adnexotropic cutaneous lymphomas’ [7]. Immune response modifiers like imiquimod and IFN-α have proven value in treatment of CTCL esp in patch and plaque stage MF and in treatment resistant cases [8, 9]. We achieved remarkable success with topical imiquimod in PUVA-resistant folliculotropic MF.

Apart from the classic Alibert-Bazin type, MF has many clinical and histologic subtypes, viz verrucous, vesicular, pustular, granulomatous, poikilodermatous, ichthyosiform and hypopigmented [10]. Though MF is primarily a disease of adults/elderly and comparatively rare in Asians, the hypopigmented variant is commoner in children and in dark skinned Asians vis-à-vis Caucasians [11]. The predominant location on the buttocks and other unexposed body areas is an important feature and clue to the diagnosis [1]. Hypopigmented MF is mostly Stage I, responds well to PUVA/UVB or topical mechlorethamine, resulting in remissions for years and long-term survival. Relapses that may occur respond well to another course of therapy [10].

Our second case was unique in its early age of onset. Possibly a chronic ‘dermatitis’ eventually led to CTCL. Clinical possibilities of eczematous dermatitis and vitiligo were considered, but unresponsiveness to prolonged treatment raised suspicion and histopathology and phenotyping provided the correct diagnosis.

Additional investigations eg CT scan of chest/abdomen/pelvis and bone marrow aspirate are required for stage IIB and above. First line of therapy in Stage IA-IIB (termed skin directed therapy) includes topical steroid, nitrogen mustard, phototherapy/photochemotherapy and total skin electron beam. Systemic therapy with variable efficacy includes extracorporeal photopheresis, immunotherapy, chemotherapy and bone marrow transplantation. A plethora of emerging newer systemic treatments hold promise viz histone deacetylase inhibitors, lymphocyte-targeted-monoclonal antibodies and combinations with bexarotene [12].

Post-remission maintenance with gradually reducing frequency of intermittent PUVA is administered for five years. Cure is defined as freedom from disease for eight years after discontinuation of all therapies [13].

To conclude, management of CTCL requires a multidisciplinary approach. The diagnosis rests on compatible clinical (morphology and distribution) and histological features. It can only be stressed that in every chronic skin disease resistant to treatment, lymphoma has to be considered as a differential diagnosis.

Conflicts of Interest

None identified

References

- 1.Mackie RM. Cutaneous lymphomas and lymphocytic infiltrates. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, Breathnach SM, editors. Vol. 1. Blackwell Science Ltd; Oxford: 1998. pp. 2373–2384. (Rook/ Wilkinson/ Ebling. Textbook of Dermatology). 6th Ed. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whittaker SJ, Marsden JR, Spittle M, Russel JR. Joint British Association of Dermatologists and UK Cutaneous Lymphoma Group guidelines for the management of primary cutaneous Tcell lymphomas. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:1095–1107. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2003.05698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willemze R, Jaffe E, Berg G. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005;105:3768–3785. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinkus H. Alopecia mucinosa: inflammatory plaques with alopecia characterized by root-sheath mucinosis. Arch Dermatol. 1957;76:419–424. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1957.01550220027005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nickoloff BJ, Wood C. Benign idiopathic versus mycosisfungoides-associated follicular mucinosis. Paediatr Dermatol. 1985;2:201–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.1985.tb01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sentis HJ, Willemze R, Scheffer E. Alopecia mucinosa progressing into mycosis fungoides: a long-term follow-up study of two patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1988;10:478–486. doi: 10.1097/00000372-198812000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser-Andrews E, Ashton R, Russell-Jones R. Pilotropic mycosis fungoides presenting with multiple cysts, comedones and alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 1999;140:141–144. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martínez-González MC, Verea-Hernando MM, Yebra-Pimentel MT, Del Pozo J, Mazaira M, Fonseca E. Imiquimod in mycosis fungoides. Eur J Dermatol. 2008;18:148–152. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2008.0352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deeths MJ, Chapman JT, Dellavalle RP, Zeng C, Aeling JL. Treatment of patch and plaque stage mycosis fungoides with imiquimod 5% cream. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akaraphanth R, Douglass MC, Lim HW. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides: treatment and a 6 1/2 year follow-up of nine patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:33–39. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(00)90006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ardigo M, Borroni G, Muscardin L, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Hypopigmented mycosis fungoides in Caucasian patients: A clinicopathologic study of seven cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49:264–270. doi: 10.1067/s0190-9622(03)00907-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bagot M. Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL)-classification, staging and treatment options. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:3–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assaf C, Sterry W. Cutaneous lymphoma. In: Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, Gilchrest BA, Paller AS, Leffell DJ, editors. Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7th ed. McGraw Hill; New York: 2008. pp. 1386–1401. [Google Scholar]