Synopsis

Tobacco use is a pervasive public health problem and the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States. This article reviews the epidemiology of tobacco use in youth, with a description of cigarettes, alternative tobacco product, and poly-tobacco use patterns among the general population and among adolescents with psychiatric and/or substance use disorders. The article also provides an update on the diagnosis and assessment of tobacco use disorder in adolescents, with a particular focus on the clinical management of tobacco use in adolescents with co-occurring disorders.

Keywords: Smoking, Tobacco Products, Tobacco Use Disorder, Adolescent, Young Adult, Smoking Cessation

Introduction/Background

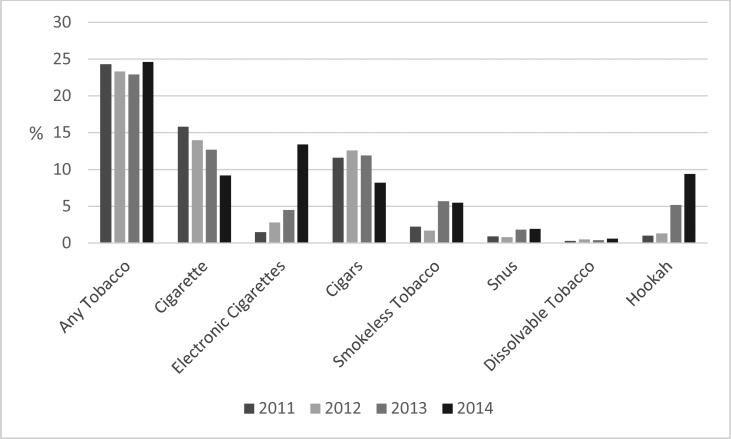

Tobacco use is a pervasive public health problem and the leading cause of preventable morbidity and mortality in the United States.1 The treatment of adolescent cigarette smoking and tobacco use disorders, in particular, continues to be a substantial public health priority. Adolescence is a critical period for neurodevelopment, and nicotine exposure during adolescence causes addiction, sustained tobacco use into adulthood, and may have lasting adverse consequences for brain development.1-3 Almost all (88% )of adult smokers start before the age of 18, and adolescents have difficulty quitting successfully.1 Although rates of cigarette use have declined in the past decade, according the Center for Disease Control's 2014 National Youth Tobacco Survey, 9.2% of high school students and 2.5% of middle school students reported current (past-month) cigarette use (Fig. 1).4 Additionally, as rates of cigarette smoking are falling, rates of alternative tobacco product (including electronic cigarettes and hookah), and dual (using cigarettes with another product) or poly-tobacco use (using any 3 or more products) remain prevalent.5,6 Many adolescents are also exposed to second hand tobacco smoke.7 Adolescents with psychiatric and/or substance use disorders are at particularly high risk for becoming tobacco dependent and are even less likely to quit than other youth.

Figure 1.

Estimated percentage of high school students who used tobacco in the preceding 30 days, by tobacco product — National Youth Tobacco Survey, United States, 2011–2014

Adapted from Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, Husten CG, Neff LJ, Apelberg BJ, Bunnell RE, Choiniere CJ, King BA, Cox S, McAfee T, Caraballo RS. Tobacco use among middle and high school students - United States, 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(14):381-385; with permission.

The 2012 U.S. Surgeon General's Report “Preventing Tobacco Use among Youth and Young Adults” describes tobacco use as a “multi-determined behavior”, with many biological, psychosocial, and environmental factors influencing its progression.1 (Box 1) Successful prevention programs have aimed to ameliorate the impact of these factors by promoting self-efficacy, refusal skills and decreasing access to tobacco products, however tobacco use continues to substantially impact the health and well-being of youth.8,9 However, if smoking continues at the current rate among youth in this country, 5.6 million of today's Americans younger than 18 (1 out of 13 youth) will die early from a smoking-related illness.10 This article will review the epidemiology of tobacco use (including cigarette, alternative tobacco product and dual/poly-tobacco use patterns) among adolescents and review the highlights of the clinical presentation, diagnosis and management of tobacco use disorders in youth.

Epidemiology

Cigarette Use

Every day, approximately 3,200 youths <18 years old initiate cigarette smoking, and 700 youths begin daily smoking. There has been a decline in cigarette smoking rates over the last 40 years. The decrease in cigarette smoking is likely due to many factors, including restrictions on advertising, taxation of cigarettes, and smoke-free laws.10 In 2014, 9.8% of high school students and 2.5% of middle school students reported past-month cigarette use. In 2013, 18.9% of 18-24 year olds reported current cigarette use.4 Historically, cigarettes have been the most common tobacco product that is used exclusively among youth (rather than in combination with another tobacco products).6 Cigarette smoking rates differ by race/ethnicity as well as geographic regions. In 2013, the prevalence of past-month cigarette smoking was higher among white students than black or Hispanic students.11 Cigarette smoking rates are also higher among youth residing in nonmetropolitan areas.12

Electronic Cigarettes (E-cigarettes)

E-cigarettes are currently the most commonly used tobacco product by U.S. adolescents.4 There are several different types of e-cigarettes, including disposable, cartridge and tank style e-cigarettes, and adolescents may refer to them by a variety of names including vape pens, e-pens, e-hookah and vape sticks (Figure 2). E-cigarette liquid (“e-juice”) contain contains nicotine, propylene glycol, vegetable glycerin, flavorants, and various additives.13 Puffing the E-cigarette (“vaping”) activates a heating element in the atomizer, and the liquid in the cartridge is vaporized into a mist that is inhaled. When youth initiate e-cigarette use, they often start with a flavored E-cigarette.14 Cartridges with nicotine typically contain 0 to 36 mg of nicotine per milliliter of solution.15 Therefore, a 5-mL vial of an 18 mg/mL solution contains 90 mg of nicotine. If accidentally or deliberately ingested, this would dose of nicotine could result in intoxication or death.16

Figure 2.

Electronic Cigarettes

From Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-Cigarettes: A Scientific Review. Circulation. 2014;129(19):1972-1986; with permission.

In 2014, 13.4% of high school students and 3.9% of middle school students reported current E-cigarette use.4 From 2011 to 2014 the prevalence of ever E-cigarette use tripled among both middle school and high school students, indicating increased experimentation.4 E-cigarettes especially appeal to cigarette smokers, however a growing proportion of e-cigarette users are non-smokers.17 Leventhal et. al demonstrated among a school-based cohort of 14-year-old high school students in Los Angeles, CA that, among students who had never used a combustible tobacco product (including cigarettes), ever-use of e-cigarettes at baseline (as compared to never-use of e-cigarettes) was positively associated with combustible cigarette and hookah use six months later.18 These emerging findings contribute to the public health community's concern that E-cigarettes may serve as a gateway product to combustible tobacco use, as well as a product with unknown safety and long-term health effects.19,20 The increasing prevalence of E-cigarette use may be attributed to heavy marketing and advertising in youth-dominated media outlets such as social networking and Internet sites, their low price, and misperception that E-cigarettes are a safer alternative to traditional cigarettes.21,22

Cigars, cigarillos and little cigars

The U.S. Department of the Treasury defines cigars as “any roll of tobacco wrapped in leaf tobacco or in any substance containing tobacco.”29 The US Department of Agriculture has classified cigars into 3 types:

-

(1)

little cigars (weighing less than 3 lb. per thousand);

-

(2)

cigarillos (weighing 3-10 lb. per thousand); and

-

(3)

large cigars (weighing more than 10 lb. per thousand) (Table 1).

Little cigars are comparable to cigarettes with regard to shape and size, they often have a filter, and adolescents may describe them as cigarettes during a clinical interview.23

Table 1.

Rate of adolescent lifetime psychiatric disorders and nicotine dependence

| By wave 5 |

||

|---|---|---|

| Baseline % | Total % | |

| Nicotine dependenceb | ||

| Ever 1+ criterion | 27.9 | 53.7 |

| Ever 3+ criteria | 10.4 | 26.1 |

| Total n ≤ | (714) | (814) |

| Anxietya | ||

| Social phobia | 3.7 | 6.3 |

| Panic | ||

| Attacks, no disorder | 2.2 | 3.8 |

| Disorder | 2.6 | 3.4 |

| Generalized anxiety | 2.3 | 4.1 |

| Any anxiety | 8.6 | 14.1 |

| Moodb | ||

| Major depression | 14.5 | 17.9 |

| Dysthymia | 1.0 | 1.7 |

| Any mood | 15.0 | 18.8 |

| Disruptivea | ||

| Attention-deficit hyperactivity | 2.1 | 2.9 |

| Oppositional defiant | 11.4 | 14.2 |

| Conduct | 14.2 | 21.2 |

| Any disruptive | 21.4 | 29.5 |

| Any psychiatric disorder | 33.9 | 43.2 |

| Total n | (814) | (814) |

*P < 0.05

**P < 0.01

***P < 0.001.

Baseline: wave 3 reports

baseline: wave 1 reports.

Adapted from Griesler PC, Hu MC, Schaffran C, Kandel DB. Comorbid psychiatric disorders and nicotine dependence in adolescence. Addiction. 2011;106(5): 1010-1020; with permission.

According to the 2014 National Youth Tobacco Survey, 8.2% of high school students and 1.9% of middle school students reported current cigar use. The prevalence of current cigar use among high school males (10.8%) was approximately double that of high school females (5.5%).4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently reported that between 2011 and 2014, cigar use decreased, which reflects the general trend of decreasing popularity of traditional combustible tobacco products among youth.

Cigar use often co-occurs with cigarette use.24, 33 The combination of cigars and cigarettes is the most common combination of dual product use among older adolescents and young adults. Similar to E-cigarettes, youth often report that cigars are appealing due to flavors.14

Smokeless Tobacco (SLT)

Despite recent declines in cigarette use among youths, declines in SLT have stalled in recent years.2 In the United States, popular forms of SLT include chewing tobacco or moist snuff. Chewing tobacco is made of long strands of tobacco, whereas snuff tobacco is a fine-grained and comes in a moist blend that usually is used orally.2

Snus and dissolvables are novel SLT products that have become increasingly available over the last 10 years. Snus are made of non-fermented, heat-cured, finely grained tobacco and are spit-free and consumed via pouches, which are placed between the cheek and gum.25 Snus have been used in Sweden since the early 19th century, but were introduced to the US in 2006.26 Snus are now marketed by major US tobacco companies with cigarette brand names (e.g., Marlboro Snus, Camel Snus).26 Dissolvables are another novel SLT that comes in pellets, strips, or sticks. They are designed to be held and dissolved in the mouth for between 3 (strips) and 30 (sticks) minutes.45 Similar to snus, dissolvables were recently introduced in US markets and bear cigarette brand names (e.g., Camel Orbs, Camel Strips).46

In 2014, 5.5 % of high school students and 1.6% of middle school students reported current SLT use, and a majority used chew/dip. Snus and dissolvables are less popular with 1.9 and 0.6% of high school students reporting current use, respectively. White males have the highest prevalence of SLT use as measured by multiple national surveys, including the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, Monitoring the Future, and the National Youth Tobacco Survey.11,12 Similar to other tobacco products, increasing age, male cigarette smoking, perceived friend approval as well as male gender predicts smokeless tobacco use.27,28

Hookah

Hookah, also known as narghile, hubble-bubble, shisha, and waterpipe, delivers a form of combustible tobacco. Commonly flavored, inhaling through the waterpipe pulls the burning tobacco's smoke through the waterpipe's water reservoir and then through a tube to which the mouthpiece is attached. Many adolescents believe that hookah smoking is relatively safe.29 Compared to the smoke from a single cigarette, the smoke from one hookah session contains up to 40 times the tar, 2 times the nicotine, 10 times the carbon monoxide and 30-50 times the carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.30-32

In 2014, 5.4% of high school students and 1.3% of middle school students reported current hookah use, 4 with rates increasing between 2011 and 2014. Hookah use increases with age and has increased in popularity among young adults. A survey of a national sample of young adults found that 25% of the sample had ever used hookah and 4% reported past 30–day use.33 Predictors of hookah smoking in college and high school students include peer pressure/social acceptability, the perception that hookah is not harmful or addictive, the presence of a family member who uses hookah, and curiosity.33

Dual Use and Poly-tobacco Use

Rates of dual and poly-tobacco use are increasing. In 2012, 6.7% of middle and high school students reported use of only one tobacco product, while 3.6% reported use of two tobacco products and 4.3% reported use of three or more tobacco products.6 In 2014, 13% of youth report using two or more tobacco products in the past month.6 Compared with those who exclusively use cigarettes, those who use cigarettes and any other form of tobacco are more likely to be male, have greater receptivity to tobacco advertising, and are more likely to use flavored tobacco products.6 Dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes in particular is also associated with the use of alcohol and other drugs, rebelliousness, sensation-seeking, and behavioral dysregulation.34 Poly-tobacco use is additionally associated black, non-Hispanic ethnicity, living with someone who uses tobacco, and perceived prevalence of peers using tobacco.6

Comorbidity with Mental Health or Developmental Disorders

Adolescents with mental health or developmental disorders may be particularly vulnerable to tobacco use. This comorbidity may be explained by a common vulnerability to both psychiatric disorders and smoking (familial/genetic or environmental), the need for self-medication, and/or common neurobiological alterations.1 Although the link between mental health disorders and tobacco use has been described extensively in adults, there is very little data describing the association among youth. Among adolescents receiving inpatient psychiatric treatment, the prevalence of cigarette of smoking has been reported to be as high as 60%.35 A 2002 review by Upadhyaya and found that adolescent cigarettes smoking is highly associated with disorders involving disruptive behavior (such as oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and ADHD), major depressive disorders, and drug and alcohol use.36 More recently, a longitudinal study of 814 adolescent lifetime cigarette smokers assessed the presence of psychiatric disorders with the Diagnostic interview schedule for children version IV.37,38 Adolescents and their parents completed five waves of data over 2 years. Overall, 33.9% reported any psychiatric disorder. (Table 2) Additionally, 60.5% of adolescents meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) criteria for nicotine dependence reported a history of a psychiatric disorders, whereas only 30.3% of adolescents with 0 symptoms of nicotine dependence reported any psychiatric disorder.

Table 2.

Smoking Cessation Pharmacotherapy

| Medication | Dosing | Initial treatment duration | Adverse effects | Contraindications | Available | Studied in Adolescents? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine Replacement Therapy | ||||||

| Nicotine patch | If >10 cigarettes/d → 21-mg patch daily; if ≤10 cigarettes/d → 14-mg patch | 8 wk | Local skin reactions, insomnia and/or vivid dreams | Pregnancy, * severe skin conditions | OTC | Yes |

| Nicotine gum | 4-mg piece if smoking ≥25 cigarettes/d, otherwise 2-mg piece. Use every 1-2 h PRN | 12 wk | Mouth soreness, hiccups, dyspepsia, jaw ache | Pregnancy, unstable angina or arrhythmias | OTC | Yes |

| Nicotine lozenge | 4-mg lozenge if smoking first cigarette within 30 min of waking, otherwise 2-mg lozenge. Use every 1-2 h PRN | 12 wk | Nausea, hiccups, heartburn, headache, cough | Pregnancy, unstable angina or arrhythmias | OTC | No |

| Nicotine inhaler | 1 puff PRN, up to 6-16 cartridges/d | 24 wk | Mouth and throat irritation, cough, rhinitis | Pregnancy, severe reactive airway disease, unstable angina or arrhythmias | Rx | No |

| Nicotine nasal spray | 1 spray each nostril, every 1-2 h PRN | 12-24 wk | Nasal irritation, nasal congestion, change in sense of smell and taste | Pregnancy, severe reactive airway disease, severe nasal disease, unstable angina or arrhythmias | Rx | Yes |

| Non-Nicotine Replacement Therapies | ||||||

| Varenicline | 0.5 mg daily × 3 d, then 0.5 mg twice a day × 4 d, then 1 mg twice a day | 12 wk | Nausea, insomnia, vivid dreams. Rare cases of agitation, changes in behavior, and suicidal ideation | Pregnancy, use cautiously in patients with psychiatric illness | Rx | No |

| Bupropion sustained release | 150 mg daily × 3 d, then increase to 150 mg twice a day | 7-12 wk | Insomnia, dry mouth. Lowers seizure threshold | Pregnancy, seizure disorder, eating disorder. Use of an MAO inhibitor in the past 14 d | Rx | Yes |

Adapted from Baldassarri SR, Toll BA, Leone FT. A Comprehensive Approach to Tobacco Dependence Interventions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(4):481-488; with permission.

Data regarding the temporality of psychiatric disorders and tobacco use remains equivocal.1 The aforementioned longitudinal cohort of adolescent smokers found that psychiatric disorders (including mood disorders) preceded the onset of tobacco use (1.3–2.4 years lower) and first nicotine dependence criterion (2.5–3.7 years lower).38 However, a 2009 systematic review of longitudinal studies examining association between depression and smoking in adolescents concluded that the relationship between depression and smoking is bidirectional.39

There are only a few studies which examine the co-occurrence of psychiatric disorders with dual use or alternative tobacco product use. A longitudinal cohort study of 486 high school students who reported past-month cigarette smoking found that, cigar, cigarillo and little cigar users showed higher levels of depression, anxiety, and antisocial behavior than nonusers, even after adjustment for frequency of cigarette smoking.40

Comorbidity with Substance Use Disorders

Use of illicit drugs or alcohol greatly increase the likelihood of tobacco use and dependence among adolescents. Studies have found that up to 80% of youth with substance use disorders report past-month tobacco use, many report daily smoking, and many become highly dependent, long-term tobacco users.36,41 For example, a recent study of 34 substance use treatment programs found that 48% of the 1,062 adolescents met criteria for tobacco dependence, 58% reported weekly tobacco use, and the sample reported a mean of 5 cigarettes smoked per day.42 Several studies have demonstrated that levels of tobacco use persist despite decreases in alcohol or drug use during substance use treatment,41,43 indicating the targeted interventions for smoking cessation are needed for youth receiving substance use treatment.

Clinical Presentation

The general examination may reveal signs that increase the probability of tobacco use. For example, the presence of smoke-odored clothing, a bottle for chew/dip spit, or cigarette packs may clue the clinician to ask more detailed questions about tobacco use. Adolescents rarely present with clinical signs that are present in adults, such as stained teeth or fingernails, wrinkles, or a hoarse voice. Adolescents in nicotine withdrawal may present with irritability, anxiety and agitation, and may ask “how long will I be here (because I need to smoke a cigarette)?”

Tobacco contains the psychoactive drug nicotine, which is central nervous system stimulant. The immediate effects of nicotine administration are tachycardia, hypertension, increased respiration, enhanced memory storage, improved concentration, and appetite suppression. Nicotine produces withdrawal symptoms about one hour after the last dose. Withdrawal symptoms are not life threatening, are usually self-limited, and include irritability, annoyance, anxiety, and cravings for nicotine.

Diagnosis

The primary method of diagnosing tobacco use is through the confidential psychiatric or medical interview. The type of tobacco product used, and the frequency and intensity of use is gauged through adolescent self-report. The 2015 American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) Clinical Practice Policy to Protect Children from Tobacco, Nicotine and Tobacco Smoke endorses several questions from the American College of Chest Physicians Tobacco Treatment Toolkit to screen for and characterize adolescent tobacco use (Box 2).20 Of note, the clinician should specifically ask about non-cigarette tobacco products, such as hookah and e-cigarettes, as adolescents may not immediately identify them as tobacco products.20

Tobacco Use Disorder is a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) diagnosis assigned to individuals who are dependent on the drug nicotine. The DSM-5 replaces the DSM-IV-TR categories of nicotine abuse and dependence with an overarching category called tobacco use disorder. The criteria for DSM-5 tobacco use disorder are the same as those for other substance use disorders. However, adolescents who smoke rarely experience significant social/occupational dysfunction due to tobacco use as many of their friends and family members may smoke, thus normalizing the behavior.

Clinicians may choose to assess the severity of cigarette smoking dependence through use of the Hooked on Nicotine Checklist or the modified Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (both available through the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute-University of Washington Library http://lib.adai.washington.edu/). Adolescents may score positively on these assessments (indicating symptoms of tobacco dependence) soon after they start smoking intermittently, and do not need to be daily or long-term smokers to report signs of addiction.44,45 Data from the 2012 National Youth Tobacco Survey demonstrated that adolescent tobacco users reported symptoms of dependence even with low levels of tobacco use.46

Breath carbon monoxide can be used to assess the presence of smoking in the last 24 hours, however in practice is rarely used outside of intensive smoking cessation treatment programs (such as contingency management based programs). Cotinine, a metabolite of nicotine, can be found in urine, saliva and blood for up to 7 days after tobacco use, but is rarely used in clinical practice to guide treatment.

According to the 2006 American Psychiatric Association's (APA) Practice Guideline for Treatment of Patients with Substance Use Disorders, 47 additional points should be incorporated into the assessment of tobacco use in patients with psychiatric disorders to determine the appropriate time for treatment initiation (Box 3).

In the case of severe psychiatric comorbidity, the clinician must weigh the risks of benefits of initiating or delaying treatment for tobacco dependence.20,47 Regardless of the timing, all adolescents with comorbid psychiatric disorders should be offered the opportunity to participate in smoking cessation treatment at some point during their psychiatric treatment course.

Brief Summary of Clinical Management

Many professional organizations endorse the importance of cigarette and tobacco cessation counseling. The 2006 APA Substance Use Treatment Guidelines encourage mental health clinicians to assess smoking status with all patients and to assist smokers in quitting.47 Additionally, both the 2008 Public Health Service's Guideline 48 and the 2015 AAP policy statement on tobacco20 recommend that all clinicians ask adolescent and young adult patients about tobacco use and provide a strong message regarding the importance of total abstinence from tobacco use. These guidelines acknowledge that smoking cessation may be more difficult for smokers with psychiatric disorders, and treatment may need to be more intensive.

Clinical management of tobacco use consists of behavioral and pharmacologic interventions, which can be used in combination.48 In general, behaviorally-based programs for smoking cessation in adolescents may be most beneficial for adolescents with mild degrees of dependence. The addition of pharmacotherapy can be considered for moderate to severely tobacco-dependent adolescents who want to stop smoking.20

Behavioral Interventions for Tobacco Use Disorders

Although a comprehensive review of the behavioral interventions for tobacco use disorders is beyond the scope of this review, several systematic reviews have outlined the evidence base surrounding these interventions for adolescents. Stanton and Grimshaw's 2013 Cochrane Review “Tobacco cessation interventions for young people” found that most studies used complex interventions that incorporated strategies from multiple health behavior theories.49 Common modalities included motivational enhancement, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and stage-based interventions using the transtheoretical model (TTM). The meta-analysis demonstrated that TTM resulted in a pooled risk ratio (RR) of 1.56 at one year (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.21 to 2.01) for cessation, motivational enhancement resulted in a RR off 1.60 (95% CI 1.28 to 2.01), and trials of CBT did not result in statistically significant changes in abstinence.

The U.S. Public Health Service 2008 Guideline and the AAP 2015 Clinical Practice Policyrecommends brief counseling for treating adolescent smokers. 20,48 The guidelines recommend the 5A model of care (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange follow-up). In this model, the clinician is encouraged to Ask all adolescents about tobacco use and about secondhand smoke exposure. Next, the clinician should Advise cessation through use of a strong message describing the personal health risks for the patient and the benefits of quitting. Advice should also address protection of oneself and others from secondhand smoke exposure. Through use of the questions/measures described above, the clinician should then Assess level of nicotine addiction, as well as readiness to make a quit attempt and/or initiate treatment. Then the clinician should assist the patient in formulating an appropriate tobacco cessation plan, which could include use of behavioral treatments and pharmacotherapy. Lastly, clinicians should Arrange for follow-up within two weeks wherein they discuss the patient's progress with the quit attempt.

Pharmacotherapy

Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT including patch, gum, inhaler and nasal spray), bupropion and varenicline are approved for the treatment of smoking cessation in adults (Table 2).50 However, there are limited studies which evaluate the efficacy of various pharmacotherapies for adolescent smoking cessation, therefore the Food and Drug Administration's labeling indicates these medications for adults older than 18 years.

In 2013, the Cochrane Group for Systemic Reviews reviewed studies evaluating the efficacy of interventions to promote smoking cessation in youth.51 The review identified one study evaluating the efficacy of nicotine replacement therapy in adolescents that met the inclusion criteria of being a randomized controlled trial/controlled trial. This double-blind, double-dummy, randomized trial of 120 adolescent daily smokers compared nicotine patch (21 mg), nicotine gum (2 and 4 mg), and a placebo patch and gum. All study participants also received cognitive-behavioral group therapy. Intent-to-treat analyses of all randomized participants showed biochemically-confirmed prolonged abstinence rates of 18% for the active-patch group, 6.5% for the active-gum group, and 2.5% for the placebo group, with a statistically significant difference between the patch and placebo group.52 A meta-analysis of 8 studies evaluating the efficacy of NRT for smoking cessation in adolescents found that abstinence rates ranged from 6.5% for the nicotine gum to 28% for the nicotine patch at 10 weeks, however these abstinence rates were not statistically significant when compared to placebo.53 Compliance with NRT varied, ranging from 29% to 85%, however adverse event rates were low.

The 2013 Cochrane Review also identified 2 studies evaluating bupropion for adolescent smoking cessation and did not find a statistically significant benefit of this pharmacotherapy.23,24 Although varenicline is approved for use in adults greater than 18 (and should be used with caution in adults with co-occurring psychiatric disorders) there are no current published studies of its use in adolescents.54 Given this evidence, the AAP recently recommended that clinicians should consider using nicotine replacement therapy for adolescents with moderate to severe substance use disorder.20 Additionally, given the lack of data regarding the safety and efficacy of e-cigarettes, the AAP also recommends that providers advise adolescents that these products should not be used for tobacco cessation.20

Considerations with Co-Occurring Psychiatric Disease or Substance Use Disorders

There are few published studies evaluating smoking cessation interventions in adolescents with co-occurring psychiatric or substance use disorders. A meta-analysis of smoking cessation trials in adults with depression, found that the addition of psychosocial mood management to standard smoking cessation treatment improved long term abstinence rates in adults with both current and past depression.55 However, there are no systematic evaluations of smoking cessation treatments in adolescents with depression. A randomized trial of 191 adolescents hospitalized in an inpatient psychiatric unit found similar rates of abstinence when comparing motivational interviewing and brief advice for treating nicotine dependence.56 At 12 months, quit rates were 14% and 9% for the motivational intervention and brief advice conditions, respectively.

A systematic review of 17 studies evaluating smoking cessation treatments among adults in substance use treatment or recovery found that NRT, behavioral support, and combination approaches appeared to increase smoking abstinence in those treated for substance use disorders.57 However, similar to psychiatric disorders there are few studies which evaluate effective interventions for adolescents with substance use disorders. For example a controlled efficacy study of 54 adolescents in substance abuse treatment compared a six-session tobacco-cessation intervention to a wait-list control group. Adolescents receiving the tobacco-cessation intervention had significantly greater point-prevalence abstinence at three-month follow-up than did those in the control group, in addition to fewer days of substance use.58 Overall, studies in adults and adolescents have shown that tobacco cessation during substance use treatment is associated with increased abstinence from other substances, decreased substance use overall, and lowered risk for relapse of alcohol and drugs.59,60

Summary

Despite great advances in tobacco control, tobacco use and secondhand smoke exposure continues to substantially impact youth. Rates of cigarette use are falling, however use of e-cigarettes, hookah and other alternative tobacco products are increasing. Youth with psychiatric or substance use disorders are particularly vulnerable to develop tobacco use disorders. All clinicians should screen adolescents for all forms of tobacco use, and provide behavioral and, when indicated, pharmacologic support for quitting. There is a small body of literature evaluating smoking cessation interventions in youth with psychiatric or substance use disorders, and future research should aim to refine smoking cessation techniques for this important population. Given the large body of evidence supporting the deleterious health effects of tobacco use during adolescence, clinicians should give a strong message on the importance of tobacco abstinence.

Box 1: Risk Factors for Tobacco Use.

Lower socio-economic status

Lower levels of academic achievement

High levels of access to tobacco products

Lack of skills (self-efficacy, refusal skills) necessary to avoid tobacco

Perceptions that tobacco use is normative and not harmful

Use of tobacco by significant others and approval of tobacco use among those persons,

Lack of parental support

From U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Preventing Tobacco Use among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, 2012.

Box 2: Questions to Screen for the Severity of Tobacco use in Adolescents.

Do any of your friends use tobacco? Do you friends use e-cigarettes, e-hookah, or vape? (this question may help open the conversation, especially for younger adolescents)

Have you ever tried a tobacco product? Which tobacco products have you used? Have you tried an e-cigarette, e-hookah, or vape?

How many times have you tried (name of tobacco product)?

How often do you use (name of tobacco product)?

Adapted from Section on Tobacco Control. Clinical Practice Policy to Protect Children From Tobacco, Nicotine, and Tobacco Smoke. Pediatrics. 2015; with permission.

Box 3: Considerations for Patients with Co-Occurring Psychiatric Disorders.

Psychiatric reasons for concern about whether this is the best time for cessation- i.e. new therapies, patient currently in crisis, other pressing psychiatric problem

The likelihood that cessation would worsen the non-nicotine-related psychiatric disorder

Signs or symptoms of other undiagnosed psychiatric or substance use disorders that might interfere with efforts to quit tobacco use

The patient's current ability to use coping skills for cessation.

From Kleber HD, Weiss RD, Anton RF, et. al. Treatment of patients with substance use disorders, second edition. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(8 Suppl):5-82; with permission.

Key Points.

Tobacco use is prevalent among adolescents, and alternative tobacco product (i.e. electronic cigarettes and hookah) use rates are rising.

Adolescents with psychiatric and/or substance use disorders are at particularly high risk of experiencing tobacco dependence and having difficulty with quitting.

Several practice guidelines recommend that clinicians ask adolescents about tobacco use and provide a strong messages regarding the importance of abstinence from all tobacco products.

Clinical management of tobacco use consists of behavioral and pharmacologic interventions, which can be used in combination.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: The Authors have nothing to disclose.

Contributor Information

Deepa R. Camenga, Yale School of Medicine, 464 Congress Avenue, Suite 260, New Haven, CT 06519.

Jonathan D. Klein, Julius B. Richmond Center, American Academy of Pediatrics, Elk Grove Village, IL, jklein@aap.org. Ph: 847-434-4322.

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RF, McDonald CG, Bergstrom HC, et al. Adolescent nicotine induces persisting changes in development of neural connectivity. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;55:432–443. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.019. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fuhrmann D, Knoll LJ, Blakemore SJ. Adolescence as a Sensitive Period of Brain Development. Trends Cogn Sci. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.07.008. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arrazola RA, Singh T, Corey CG, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students - United States, 2011-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(14):381–385. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arrazola RA, Dube SR, Kaufmann RB, et al. Tobacco use among middle and high school students United States, 2000-2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(33):1063–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee YO, Hebert CJ, Nonnemaker JM, et al. Youth tobacco product use in the United States. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):409–415. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3202. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Homa DM, Neff LJ, King BA, Caraballo RS, et al. Vital signs: disparities in nonsmokers' exposure to secondhand smoke--United States, 1999-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(4):103–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas RE, McLellan J, Perera R. School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;4:CD001293. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001293.pub3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001293.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grucza RA, Plunk AD, Hipp PR, et al. Long-term effects of laws governing youth access to tobacco. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(8):1493–1499. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301123. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2012.301123. Pmc3710295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . The Health Consequences of Smoking 50 years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; Atlanta, GA: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kann L, Kinchen S, Shanklin SL, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance--United States, 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2014;63(Suppl 4):1–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Subgroup Trends Among Adolescents in the Use of Various Licit and Illicit Drugs, 1975-2013 (Monitoring the Future Occcasional Paper 81) Institute of Social Research. The University of Michigan; Ann Arbor, MI: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grana R, Glantz SA. [October 20, 2015];Background paper on E-cigarettes (electronic nicotine delivery systems) Available online at http://escholarship.org/uc/item/13p2b72n2013.

- 14.Ambrose BK, Day HR, Rostron B, et al. Flavored tobacco product use among us youth aged 12-17 years, 2013-2014. JAMA. 2015:1–3. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13802. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cameron JM, Howell DN, White JR, et al. Variable and potentially fatal amounts of nicotine in e-cigarette nicotine solutions. Tob Control. 2014;23(1):77–78. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050604. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hajek P, Etter J-F, Benowitz N, Eissenberg T, et al. Electronic cigarettes: Review of use, content, safety, effects on smokers, and potential for harm and benefit. Addiction. 2014;109(11):1801–1810. doi: 10.1111/add.12659. doi: 10.1111/add.12659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bunnell RE, Agaku IT, Arrazola RA, et al. Intentions to smoke cigarettes among never-smoking US middle and high school electronic cigarette users: National Youth Tobacco Survey, 2011-2013. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(2):228–235. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu166. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu166. PMC4515756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leventhal AM, Strong DR, Kirkpatrick MG, et al. Association of electronic cigarette use with initiation of combustible tobacco product smoking in early adolescence. JAMA. 2015;314(7):700–707. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8950. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.8950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grana RA. Electronic cigarettes: a new nicotine gateway? J Adolesc Health. 2013:135–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.11.007. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Section on Tobacco Control Clinical Practice Policy to Protect Children From Tobacco, Nicotine, and Tobacco Smoke. Pediatrics. 2015 doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3108. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ambrose BK, Rostron BL, Johnson SE, et al. Perceptions of the relative harm of cigarettes and e-cigarettes among U.S. youth. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2 Suppl 1):S53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.016. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong G, Morean ME, Cavallo DA, et al. Reasons for Electronic Cigarette Experimentation and Discontinuation Among Adolescents and Young Adults. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(7):847–854. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu257. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntu257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delnevo CD, Hrywna M. “A Whole ’Nother Smoke” or a Cigarette in Disguise: How RJ Reynolds Reframed the Image of Little Cigars. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(8):1368–1375. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101063. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.101063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cohn A, Cobb CO, Niaura RS, et al. The Other Combustible Products: Prevalence and Correlates of Little Cigar/Cigarillo Use Among Cigarette Smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv022. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galanti MR, Rosendahl I, Wickholm S. The development of tobacco use in adolescence among “snus starters” and “cigarette starters”: an analysis of the Swedish “BROMS” cohort. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10(2):315–323. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825858. doi: 10.1080/14622200701825858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mejia AB, Ling PM. Tobacco industry consumer research on smokeless tobacco users and product development. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):78–87. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.152603. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2008.152603. Pmc2791252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tomar SL, Hatsukami DK. Perceived risk of harm from cigarettes or smokeless tobacco among U.S. high school seniors. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9(11):1191–1196. doi: 10.1080/14622200701648417. doi: 10.1080/14622200701648417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Agaku IT, Ayo-Yusuf OA, Vardavas CI, et al. Use of conventional and novel smokeless tobacco products among US adolescents. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):e578–586. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0843. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith JR, Novotny TE, Edland SD, et al. Determinants of hookah use among high school students. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(7):565–572. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr041. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eissenberg T, Shihadeh A. Waterpipe tobacco and cigarette smoking: direct comparison of toxicant exposure. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37(6):518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.014. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.07.014. 2805076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sepetdjian E, Shihadeh A, Saliba NA. Measurement of 16 polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in narghile waterpipe tobacco smoke. Food Chem Toxicol. 2008;46(5):1582–1590. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2007.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shihadeh A, Saleh R. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, carbon monoxide, “tar”, and nicotine in the mainstream smoke aerosol of the narghile water pipe. Food Chem Toxicol. 2005;43(5):655–661. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villanti AC, Cobb CO, Cohn AM, et al. Correlates of hookah use and predictors of hookah trial in U.S. young adults. Am J Prev Med. 2015;48(6):742–746. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.010. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wills TA, Knight R, Williams RJ, et al. Risk factors for exclusive e-cigarette use and dual e-cigarette use and tobacco use in adolescents. Pediatrics. 2015;135(1):e43–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0760. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0760. PMC4279062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramsey SE, Brown RA, Strong DR, et al. Cigarette smoking among adolescent psychiatric inpatients: prevalence and correlates. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2002;14(3):149–153. doi: 10.1023/a:1021134503026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Upadhyaya HP, Deas D, Brady KT, et al. Cigarette smoking and psychiatric comorbidity in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(11):1294–1305. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200211000-00010. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200211000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, et al. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39(1):28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Griesler PC, Hu MC, Schaffran C, et al. Comorbid psychiatric disorders and nicotine dependence in adolescence. Addiction. 2011;106(5):1010–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03403.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39*.Chaiton MO, Cohen JE, O'Loughlin J, et al. A systematic review of longitudinal studies on the association between depression and smoking in adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-356. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schuster RM, Hertel AW, Mermelstein R. Cigar, cigarillo, and little cigar use among current cigarette-smoking adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(5):925–931. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts222. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts222. PMC3621583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cole J, Stevenson E, Walker R, et al. Tobacco use and psychiatric comorbidity among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;43(1):20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.024. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coleman-Cowger VH, Catlin ML. Changes in tobacco use patterns among adolescents in substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2013;45(2):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.02.004. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shelef K, Diamond GS, Diamond GM, Myers MG. Changes in Tobacco Use Among Adolescent Smokers in Substance Abuse Treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2009;23(2):355–361. doi: 10.1037/a0014517. doi: 10.1037/a0014517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scragg R, Wellman RJ, Laugesen M, DiFranza JR. Diminished autonomy over tobacco can appear with the first cigarettes. Addict Behav. 2008;33(5):689–698. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.12.002. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DiFranza JR, Coleman M, St Cyr D. A Comparison of the Advertising and Accessibility of Cigars, Cigarettes, Chewing Tobacco, and Loose Tobacco. Prev Med. 1999;29(5):6–6. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0553. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Apelberg BJ, Corey CG, Hoffman AC, Schroeder MJ, Husten CG, Caraballo RS, Backinger CL. Symptoms of Tobacco Dependence Among Middle and High School Tobacco Users: Results from the 2012 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(2, Supplement 1):S4–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.013. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleber HD, Weiss RD, Anton RF. Treatment of patients with substance use disorders, second edition. American Psychiatric Association. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(8 Suppl):5–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fiore MC, Jaen CR, Baker TB, Bailey WC, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Public Health Services; Rockville, MD: May, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stanton W, Baade P, Moffatt J. Predictors of smoking cessation processes among secondary school students. Substance Use and Misuse. 2006;41(13):1683–1694. doi: 10.1080/10826080601006284. doi: 10.1080/10826080601006284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baldassarri SR, Toll BA, Leone FT. A Comprehensive Approach to Tobacco Dependence Interventions. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015;3(4):481–488. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.04.007. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51*.Stanton A, Grimshaw G. Tobacco cessation interventions for young people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:Cd003289. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub5. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003289.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moolchan ET, Robinson ML, Ernst M, et al. Safety and efficacy of the nicotine patch and gum for the treatment of adolescent tobacco addiction. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):e407–414. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1894. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53*.King JL, Pomeranz JL, Merten JW. A systematic review and meta-evaluation of adolescent smoking cessation interventions that utilized nicotine replacement therapy. Add Behav. 2015;52:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.08.007. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bailey SR, Crew EE, Riske EC, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of pharmacotherapies to aid smoking cessation in adolescents. Paediatr Drugs. 2012;14(2):91–108. doi: 10.2165/11594370-000000000-00000. doi: 10.2165/11594370-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55*.van der Meer RM, Willemsen MC, Smit F, et al. Smoking cessation interventions for smokers with current or past depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;8:Cd006102. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006102.pub2. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006102.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brown RA, Ramsey SE, Strong DR, et al. Effects of motivational interviewing on smoking cessation in adolescents with psychiatric disorders. Tobacco control. 2003;12(Suppl 4):IV3–10. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.suppl_4.iv3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57*.Thurgood SL, McNeill A, Clark-Carter D, et al. A Systematic Review of Smoking Cessation Interventions for Adults in Substance Abuse Treatment or Recovery. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015 doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv127. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Myers MG, Brown SA. A controlled study of a cigarette smoking cessation intervention for adolescents in substance abuse treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(2):230–233. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.2.230. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.19.2.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Dios MA, Vaughan EL, Stanton CA, et al. Adolescent tobacco use and substance abuse treatment outcomes. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37(1):17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.09.006. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60*.Prochaska JJ, Delucchi K, Hall SM. A meta-analysis of smoking cessation interventions with individuals in substance abuse treatment or recovery. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(6):1144–1156. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1144. 10.1037/0022-006x.72.6.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grana R, Benowitz N, Glantz SA. E-Cigarettes: A Scientific Review. Circulation. 2014;129(19):1972–1986. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.007667. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.114.007667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]