Abstract

The hypothesis of metabolically healthy obesity posits that adverse health effects of obesity are largely avoided when obesity is accompanied by a favorable metabolic profile. We tested this hypothesis with depressive symptoms as the outcome using cross-sectional data on obesity, metabolic health and depressive symptoms. Data were extracted from 8 studies and pooled for individual-participant meta-analysis with 30,337 men and women aged 15 to 105 years (mean age=46.1). Clinic measures included height, weight, and metabolic risk factors (high blood pressure, high triglycerides, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high C-reactive protein, and high glycated hemoglobin). Depressive symptoms were assessed using clinical interview or standardized rating scales. The pooled sample comprised 7,673 (25%) obese participants (body mass index≥30kg/m2). Compared to all non-obese individuals, the odds ratio for depressive symptoms was higher in metabolically unhealthy obese individuals with 2 or more metabolic risk factors (1.45; 95%CI=1.30, 1.61) and for metabolically healthy obese with ≤1 metabolic risk factor (1.19; 95%CI=1.03, 1.37), adjusted for sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Metabolically unhealthy obesity was associated with higher depression risk (odds ratio=1.23, 95%CI=1.05, 1.45) compared to metabolically healthy obesity. These associations were consistent across studies with no evidence for heterogeneity in estimates (all I2-values<4%). In conclusion, obese persons with a favorable metabolic profile have a slightly increased risk of depressive symptoms compared with non-obese, but the risk is greater when obesity is combined with an adverse metabolic profile. These findings suggest that metabolically healthy obesity is not a completely benign condition in relation to depression risk.

Keywords: Adolescent; Adult; Psychiatric Status Rating Scales; Risk Factors; Age Distribution; Young Adult; Aged; Aged, 80 and over; Blood Pressure; Body Mass Index; C-Reactive Protein; Cross-Sectional Studies; Female; Depression; Health Status; Hemoglobin A, Glycosylated; Humans; Lipids; Male; Middle Aged; Obesity

Introduction

Obesity is an established risk factor for cardiovascular disease and some cancers, but may also affect mental health.1–5 Summary estimates from meta-analyses of observational studies support an increased risk of depression among the obese,1, 4, 6 although this association may not be universal.7–9 It has been suggested that the adverse health consequences of obesity may depend on whether other metabolic risk factors are present.10–15 Not all obese individuals suffer from common metabolic complications of obesity, such as high blood pressure, high triglycerides, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and elevated inflammatory markers, and such obesity is regarded as metabolically healthy.16 The hypothesis of “metabolically healthy obesity” postulates that obesity is not a health risk in those free from metabolic abnormalities,13 but evidence for the hypothesis is inconsistent across health outcomes.12, 16, 17

Only few studies have examined the metabolically healthy obesity hypothesis in relation to mental health. The hypothesis was recently tested in the English Longitudinal Study of Aging (ELSA),18 in which obesity appeared to be associated with depression risk more strongly in metabolically unhealthy obese than in metabolically healthy obese participants. However, the difference between the obesity groups was modest, and it is unknown whether these results are apparent in other populations. We pooled individual-participant data from 8 studies with over 30,000 men and women aged 15 to 105 years. In doing so, we are able to examine whether obesity is differentially associated with depressive symptoms in metabolically healthy and unhealthy individuals, and also whether specific metabolic risk factors, if any, contribute to this difference.

Methods

Participants

We searched the data collections of the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR; http://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/) and the Economic and Social Data Service (ESDS; http://www.esds.ac.uk/) to identify eligible large-scale cohort studies. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they contained data on obesity, five metabolic risk factors (blood pressure, HDL, triglycerides, blood glucose, and CRP inflammation), and depressive symptoms, and had a sufficiently large sample size (n>1000). We located 7 such cohorts: the Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Aging Study (CRELES; n=1731) from 2005;19 the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS; n=1214) biomarker sub-study from 2004–2009;20 the British National Child Development Study (NCDS; n=7237) biomedical sub-study from 2002–2004;21 the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III; n=7790) from 1988–1994; the three more recent continuous National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) from 2005–2006 (n=1998), 2007–2008 (n=2238), and 2009–2010 (n=2406).22, 23 In addition, we included data from the British Whitehall II study (n=5723),24 which we have previously used to examine the association between obesity and mental health.25–27 All the studies included are well characterized (details of the cohorts available in Online Supplementary Material) and were approved by the relevant local ethics committees.

Measures

In all studies, height and weight were measured in a medical examination. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kg/(height in m)2. Obesity was defined as BMI ≥ 30kg/m2 and overweight as BMI≥25kg/m2 but below 30kg/m2. Metabolic risk markers included high blood pressure (>130mmHg systolic or >85mmHg diastolic), high triglycerides (>1.7mmol/L), low HDL cholesterol (<1.03mmol/L in men, <1.29mmol/L in women), impaired glucose metabolism (glycated hemoglobin HA1c > 6%), and high C-reactive protein (CRP>3.0mg/dL), as used previously in the definition of metabolically healthy obesity.28 Except for the NCDS sample, in which detailed medication information was not available, high blood pressure was assigned also to individuals using hypertensive medication, and high blood glucose was assigned to individuals using diabetic medication. Metabolically unhealthy obesity was defined as having a BMI ≥ 30kg/m2 and 2 or more metabolic risk factors (high blood pressure, high triglycerides, low HDL cholesterol, impaired glucose metabolism, high CRP). Metabolically healthy obesity refers to obese individuals with no or one metabolic risk factor.

Depressive symptoms were assessed with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D)29 in MIDUS and Whitehall II; Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)30 in CRELES; depression score of the Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R)31 mental health interview in NCDS; Diagnostic Interview Schedule (DIS)32 in NHANES III; and Depression Screening Questionnaire based on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)33 in the 3 continuous NHANES studies. All depression measures were categorized into dichotomous outcome variables using predefined thresholds.

Statistical analysis

We examined the association of obesity (0=BMI<30, 1=BMI≥30) and metabolic health status (0=no or one metabolic risk factor, 1=two or more metabolic risk factors) with a binary depressive symptoms outcome using logistic regression, adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity (0=White/Caucasian, 1=Black/African, 2=Other) in the basic model. Individuals with BMI≤18.5 were excluded from the analysis. The associations of obesity and depressive symptoms in metabolically healthy and unhealthy individuals were calculated based on the main and interaction effects of the logistic regression model. The cohort-specific estimates were then pooled in a random-effect meta-analysis, and heterogeneity between studies was examined by I2 statistic. To examine whether metabolic health moderated the associations of overweight with depressive symptoms, the analysis was repeated with overweight (BMI above 25kg/m2 but below 30kg/m2) as the body weight risk group, using normal weight as the reference category, and excluding obese and underweight individuals from the analysis. Appropriate sampling weights were used in CRELES and all NHANES studies.

In additional analysis, the models were further adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, smoking (0=non-smoker, 1=ex-smoker, 2=current smoker), physical activity (self-reported frequency of leisure-time moderate and/or vigorous activity), alcohol consumption (self-reported frequency of drinking alcohol), and educational level (or occupational level in Whitehall II). Metabolically unhealthy individuals may also carry more weight, especially abdominal visceral fat,34 than their metabolically healthy counterparts in the same obesity category, which might be related to differences in depressive symptoms. This possibility was examined by adjusting the analysis for waist circumference. To avoid overlap between obesity status and waist circumference in the same model, we created a new variable indicating the participant’s deviation from the average waist circumference of his/her obesity status group (non-obese or obese), and included the interaction effect between this variable and obesity status in the analysis to take into account differences in waist circumference among the non-obese and obese participants.

In order to keep the number of participants constant across different models, all missing values of covariates were imputed using linear regression imputation with age, sex, and race/ethnicity as the predictor variables. Less than 5% of the observations were imputed in each study. We used logistic regression to investigate the associations of covariates with metabolically healthy obesity (outcome variable 0=metabolically healthy obese, 1=metabolically unhealthy obese). For this analysis, alcohol consumption, physical activity, and education were standardized into z-scores (mean=0, SD=1) in each study to make the estimates comparable across studies for a meta-analysis; waist circumference and smoking status were used as unstandardized variables.

Results

Study-specific characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. Depending on the study, 16% to 46% of obese participants were defined as metabolically healthy, that is, with no more than 1 metabolic risk factor. In the pooled analysis with normal weight as the reference category, obesity was associated with higher risk of depressive symptoms (OR=1.35, CI=1.22, 1.50) whereas overweight was not (OR=1.01, CI=0.92, 1.11). The risk of depressive symptoms increased in a dose-response pattern with increasing number of metabolic risk factors with odds ratios of 1.00 (no metabolic risks, reference group), 1.32 (one risk factor), 1.45 (two risk factors), 1.99 (three risk factors), and 2.06 (four or five risk factors). A linear trend analysis indicated that the risk of depressive symptoms was OR=1.22 (CI=1.15, 1.29) higher for every additional metabolic risk factor in the pooled sample.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included cohorts

| CRELES | MIDUS | NCDS | NHANES III | NHANES 2005 | NHANES 2007 | NHANES 2009 | Whitehall II | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants (n) | 1,731 | 1,214 | 7,237 | 7,790 | 1,998 | 2,238 | 2,406 | 5,723 |

| Age (Years, SD) | 73.2 (8.3) | 54.6 (11.7) | 46.0 | 26.8 (7.1) | 45.1 (19.8) | 49.4 (18.4) | 48.0 (18.4) | 61.0 (5.9) |

| Age range (min-max) | 60–105 | 34–84 | 46 | 15–39 | 18–85 | 18–80 | 18–80 | 50–74 |

| Sex (% females) | 54.7 (946) | 56.3 (683) | 49.7 (3,594) | 53.7 (4,187) | 50.8 (1,014) | 49.7 (1,112) | 51.4 (1,236) | 28.1 (1,606) |

| Ethnic background | ||||||||

| White/Caucasian | - | 93.6 (934) | - | 28.2 (2,193) | 48.5 (969) | 47.9 (1,072) | 47.8 (1,150) | 92.4 (5,284) |

| Black/African | - | 2.7 (27) | - | 32.9 (2,566) | 22.9 (458) | 18.7 (419) | 16.4 (394) | 4.8 (272) |

| Other | - | 3.7 (37) | - | 38.9 (3,031) | 28.6 (571) | 33.4 (747) | 35.8 (862) | 2.9 (163) |

| Depressive symptoms | 9.7 (168) | 16.1 (195) | 16.5 (1,195) | 4.9 (383) | 5.9 (118) | 8.4 (188) | 8.6 (206) | 15.0 (861) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2, SD) | 26.9 (4.8) | 29.7 (6.5) | 27.3 (4.8) | 26.2 (5.8) | 29.1 (7.2) | 28.8 (6.2) | 29.2 (6.8) | 26.8 (4.3) |

| Normal weight | 37.1 (643) | 23.6 (287) | 34.6 (2,502) | 51.0 (3,976) | 31.2 (623) | 28.7 (643) | 28.0 (673) | 36.1 (2,066) |

| Overweight | 40.9 (708) | 35.7 (433) | 41.9 (3,030) | 28.4 (2,213) | 32.7 (654) | 35.7 (798) | 34.5 (831) | 45.2 (2,584) |

| Obese | 22.0 (380) | 40.7 (494) | 23.6 (1,705) | 20.6 (1,601) | 36.1 (721) | 35.6 (797) | 37.5 (902) | 18.7 (1,073) |

| Hypertension | 81.2 (1,406) | 67.1 (814) | 41.6 (3,007) | 20.0 (1,560) | 41.7 (834) | 45.5 (1,018) | 44.0 (1,058) | 54.7 (3,128) |

| Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) | 27.2 (470) | 37.9 (460) | 4.1 (300) | 5.7 (443) | 15.7 (314) | 23.3 (521) | 22.5 (542) | 8.4 (481) |

| Low HDL cholesterol | 58.5 (1,013) | 29.7 (361) | 11.0 (793) | 34.6 (2,699) | 21.8 (435) | 28.6 (641) | 30.7 (739) | 10.7 (614) |

| High triglycerides | 44.2 (765) | 27.5 (334) | 49.6 (3,589) | 20.1 (1,563) | 30.1 (601) | 29.8 (667) | 26.5 (638) | 25.8 (1,478) |

| Metabolic risk factors | ||||||||

| None | 5.8 (100) | 14.4 (175) | 29.0 (2,096) | 45.5 (3,541) | 31.5 (630) | 28.9 (647) | 29.7 (714) | 29.4 (1,683) |

| One | 22.2 (385) | 27.8 (338) | 32.3 (2,337) | 33.7 (2,629) | 33.0 (659) | 30.1 (674) | 30.8 (742) | 36.5 (2,091) |

| Two | 29.6 (513) | 25.0 (304) | 26.7 (1,931) | 15.6 (1,217) | 22.0 (439) | 23.1 (516) | 21.8 (525) | 21.8 (1,246) |

| Three | 28.9 (501) | 20.3 (246) | 9.3 (671) | 4.5 (351) | 9.3 (185) | 11.7 (262) | 12.0 (288) | 8.9 (510) |

| Four | 12.5 (216) | 9.1 (111) | 2.5 (178) | 0.6 (49) | 3.6 (71) | 5.4 (120) | 4.9 (119) | 2.9 (165) |

| Five | 0.9 (16) | 3.3 (40) | 0.3 (24) | 0.0 (3) | 0.7 (14) | 0.8 (19) | 0.7 (18) | 0.5 (28) |

| Metabolically healthy obese (%) * | 14.8 | 22.1 | 32.4 | 52.9 | 43.8 | 43.1 | 44.8 | 37.3 |

Note: Values are unweighted percentages (and numbers) of participants unless otherwise indicated. Data are shown for participants included in the main analyses. CRELES=Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Aging Study, MIDUS=Midlife in the United States, NCDS=British National Child Development Study, NHANES=National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.

Percentage of obese (BMI≥30) participants.

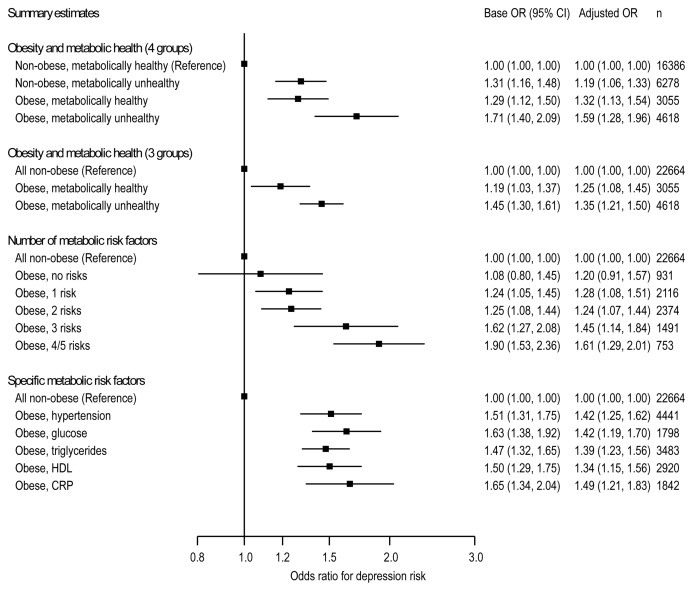

Figure 1 shows that compared to metabolically healthy non-obesity, higher risk of depressive symptoms was observed both for metabolically unhealthy non-obesity (OR=1.31, CI=1.16, 1.48) and metabolically healthy obesity (OR=1.29, CI=1.12, 1.50). This association with depressive symptoms was significantly stronger for metabolically unhealthy obesity (OR=1.71, CI=1.40, 2.09), as indicated by the non-overlapping confidence intervals and point estimates of the two groups. There was no evidence for heterogeneity in the effect sizes for these associations across studies (all I2 = 0%, p>0.57). The association between overweight (BMI between 25kg/m2 and 30kg/m2) and depressive symptoms appeared to be stronger for metabolically unhealthy overweight (OR=1.29, CI=0.84, 1.99) than for metabolically healthy overweight (OR=0.98, CI=0.87, 1.11) but these associations were not statistically significant, as indicated by the overlapping point estimates and confidence intervals of the two groups.

Figure 1.

Pooled estimates across 8 studies for the risk of depressive symptoms associated in obese individuals compared to non-obese individuals (total n=30,337). Metabolically healthy status is defined as having ≤1 metabolic risk factors. The base models are adjusted for age, sex, and race/ethnicity. The fully adjusted models are further adjusted for smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption, education, and waist circumference deviation from the person’s obesity group mean waist circumference value. See online supplementary material for study-specific results.

Figure 1 also shows that compared to all non-obese participants (metabolically healthy or unhealthy), depression risk was higher for metabolically unhealthy obesity (OR=1.45, CI=1.30, 1.61) than for metabolically healthy obesity (OR=1.19, CI=1.03, 1.37). The risk of depressive symptoms associated with obesity increased almost linearly with the number of metabolic risk factors, but there were no substantial differences between specific metabolic risk factors in contributing to this association (Figure 1). Obese individuals with no metabolic risk factors did not have elevated depression risk (OR=1.08) although adjusting for baseline covariates increased this summary estimate to OR=1.20 (CI=0.91, 1.57; Figure 1).

Compared to metabolically healthy obesity, metabolically unhealthy obesity was associated with OR=1.23 (CI=1.05, 1.45) higher depression risk in the base model adjusted for sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Among the obese individuals only, higher risk of being metabolically unhealthy compared to being metabolically healthy was associated with current smoking (OR=1.50, CI=1.28, 1.76), lower physical activity (OR=0.83 per 1SD difference, CI=0.76, 0.90), higher waist circumference (OR=1.27 per 5cm, CI=1.21, 1.33), and lower education (OR=0.81 per 1SD difference, CI=0.74, 0.88) but not alcohol consumption. Adjusting for smoking, physical activity, alcohol consumption, waist circumference deviation, and education attenuated the risk difference in depressive symptoms between metabolically healthy and unhealthy obesity (OR=1.10, CI=0.93, 1.30 in the fully adjusted model). The increasing depression risk associated with increasing number of metabolic risk factors co-occurring with obesity was also attenuated but remained substantially similar to the base model, as reported in the “Adjusted OR” column of Figure 1.

Details of the study-specific results are reported in Supplementary Figures 1 to 11.

Comment

Results from 8 cohort studies with over 30,000 participants suggest that metabolically healthy and unhealthy obesity is associated with an increased risk of depressive symptoms, but the metabolically unhealthy obese have 23% higher odds of depressive symptoms compared to the metabolically healthy obese (defined as no more than 1 metabolic risk factor). The elevated depression risk associated with obesity increased almost linearly with increasing number of metabolic risk factors co-occuring with obesity. These findings support the hypothesis of metabolically healthy obesity in depression,18 but only partly as the risk of depressive symptoms among metabolically healthy obese was higher than in persons with normal weight.

The main strength of the current study is its multi-cohort design with a large pooled sample size. While results from literature-based meta-analyses can be biased by selective publication of positive results, the present analysis was based on publicly available databases and not published results. It is reasonable to assume that these datasets are generally representative of observational cohort studies in the United States and United Kingdom, so the present results are unlikely to be subject to a major publication bias. With the large pooled sample size, we were able to quantify robustly associations that could not have been estimated precisely in single studies. Depressive symptoms were assessed with clinical interviews in two of the eight cohorts studies and with three different self-rating scales in six of the other cohort studies. This variability did not seem to introduce substantial heterogeneity in the associations, as the risk for depressive symptoms associated with obesity was consistent across cohorts.

The present analysis was based on cross-sectional data, so temporal direction of the association could not be investigated. Longitudinal data suggest that the association between obesity and depression is bidirectional, so that obesity increases later depression risk and depression increases later obesity risk.1 Similar bidirectional associations have been reported for associations between metabolic syndrome and depression,35 and diabetes and depression,36 suggesting that obesity, metabolic abnormalities, and depressive symptoms may be connected via multiple pathways. A recent report from a 2 year follow-up of study members in the ELSA,18 using a 2-year longitudinal setting, showed that metabolically unhealthy obese people had a higher risk of future depression than the metabolically unhealthy obese.”

The mechanisms determining metabolically healthy and unhealthy obesity states are not well known.11, 12, 16, 17 One crucial factor may be where the person’s fat is stored, with excess visceral fat being more detrimental for metabolic health than excess subcutaneous fat.16 In addition, our current analysis showed that people classified as metabolically healthy obese and metabolically unhealthy obese have different health characteristics, such as lower smoking prevalence, higher physical activity and higher educational level, suggesting that both physiological and behavioral factors may be involved. There are also several common biological states that link obesity and metabolic factors to depression, including inflammation,37–39 impaired glycaemic control40,41 and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) axis.42, 43 A different set of factors may distinguish the depression risk of metabolically healthy obese individuals from non-obese individuals, including negative self-image, social stigma and discrimination, functional limitations in daily life, and physical inactivity.3, 44, 45

In conclusion, the present results from a pooled analysis of men and women aged 15 to 105 indicate that metabolically healthy obesity is associated with higher risk of depressive symptoms than being non-obese, and that this elevated risk increases with increasing number of metabolic risk factors co-occuring with obesity. The findings suggest that metabolically healthy obesity is not a completely benign condition in relation to mental health risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Academy of Finland (grant numbers: 124322, 124271 and 132944); the BUPA Foundation, UK; Medical Research Council (MRC, K013351); the US National Institutes of Health (R01HL036310; R01AG034454), and the Finnish Work Environment Fund. The Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology is supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the Economic and Social Research Council, the Medical Research Council and the University of Edinburgh as part of the cross-council Lifelong Health and Wellbeing initiative. MH is supported by the British Heart Foundation (RE/10/005/28296). G.D.B. is a Wellcome Trust Fellow. M.K. is an Economic and Social Research Council Professor.

Footnotes

None of the authors have any conflicting interests.

The study sponsors did not contribute to the study design and had no role in data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or the writing of the report.

References

- 1.Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx B, et al. Overweight, obesity, and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67:220–229. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wardle J, Chida Y, Gibson EL, Whitaker KL, Steptoe A. Stress and adiposity: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Obesity. 2011;19:771–778. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markowitz S, Friedman MA, Arent SM. Understanding the relation between obesity and depression: Causal mechanisms and implications for treatment. Clin Psychol-Sci Pr. 2008;15:1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gariepy G, Nitka D, Schmitz N. The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obesity. 2010;34:407–419. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2009.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jokela M, Elovainio M, Keltikangas-Järvinen L, Batty GD, Hintsanen M, Seppälä I, et al. Body mass index and depressive symptoms: instrumental-variables regression with genetic risk score. Genes Brain Behav. 2012;11:942–948. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2012.00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Wit L, Luppino F, van SA, Penninx B, Zitman F, Cuijpers P. Depression and obesity: A meta-analysis of community-based studies. Psychiat Res. 2010;178:230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawlor DA, Hart CL, Hole DJ, Gunnell D, Smith GD. Body mass index in middle life and future risk of hospital admission for psychoses or depression: findings from the Renfrew/Paisley study. Psychol Med. 2007;37:1151–1161. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707000384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palinkas LA, Wingard DL, Barrett Connor E. Depressive symptoms in overweight and obese older adults: A test of the “jolly fat” hypothesis. J Psychosom Res. 1996;40:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(95)00542-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gariepy G, Wang JL, Lesage AD, Schmitz N. The longitudinal association from obesity to depression: Results from the 12-year National Population Health Survey. Obesity. 2010;18:1033–1038. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bluher M. The distinction of metabolically ‘healthy’ from ‘unhealthy’ obese individuals. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:38–43. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283346ccc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Denis GV, Obin MS. ‘Metabolically healthy obesity’: origins and implications. Mol Aspects Med. 2013;34:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Despres JP. What is “metabolically healthy obesity”? From epidemiology to pathophysiological insights. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2283–2285. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortega FB, Lee DC, Katzmarzyk PT, Ruiz JR, Sui X, Church TS, et al. The intriguing metabolically healthy but obese phenotype: cardiovascular prognosis and role of fitness. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:389–397. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Singh-Manoux A, Czernichow S, Elbaz A, Dugravot A, Sabia S, Hagger-Johnson G, et al. Obesity phenotypes in midlife and cognition in early old age: the Whitehall II cohort study. Neurology. 2012;79:755–762. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182661f63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamer M, Stamatakis E. Metabolically healthy obesity and risk of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2482–2488. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-3475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stefan N, Häring HU, Hu FB, Schulze MB. Metabolically healthy obesity: epidemiology, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinol. 2013;1:152–162. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips CM. Metabolically healthy obesity: Definitions, determinants and clinical implications. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2013;14:219–227. doi: 10.1007/s11154-013-9252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamer M, Batty GD, Kivimäki M. Risk of future depression in people who are obese but metabolically healthy: the English longitudinal study of ageing. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17:940–945. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosero-Bixby L, XF, WHD . CRELES: Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Aging Study, 2005 (Costa Rica Estudio de Longevidad y Envejecimiento Saludable) [Computer file] Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2010. Sep 13, ICPSR26681-v2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryff CD, Seeman T, Weinstein M. National Survey of Midlife Development in the United States (MIDUS II): Biomarker Project, 2004–2009 [Computer file] Vol. 2010 Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]; 2010. Sep 24, ICPSR29282-v1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Power C, Elliott J. Cohort profile: 1958 British birth cohort (National Child Development Study) Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35:34–41. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey Data. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shay CM, Ning H, Daniels SR, Rooks CR, Gidding SS, Lloyd-Jones DM. Status of cardiovascular health in US adolescents: prevalence estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 2005–2010. Circulation. 2013;127:1369–1376. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.001559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marmot M, Brunner E. Cohort profile: The Whitehall II study. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:251–256. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kivimäki M, Batty GD, Singh-Manoux A, Nabi H, Sabia S, Tabak AG, et al. Association between common mental disorder and obesity over the adult life course. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195:149–155. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.057299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kivimäki M, Lawlor DA, Singh-Manoux A, Batty GD, Ferrie JE, Shipley MJ, et al. Common mental disorder and obesity-insight from four repeat measures over 19 years: prospective Whitehall II cohort study. BMJ. 2009;339:b3765. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kivimäki M, Jokela M, Hamer M, Geddes J, Ebmeier K, Kumari M, et al. Examining overweight and obesity as risk factors for common mental disorder using FTO genotype-instrumented analysis: the Whitehall II study, 1985–2004. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:421–429. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wildman RP, Muntner P, Reynolds K, McGinn AP, Rajpathak S, Wylie-Rosett J, et al. The obese without cardiometabolic risk factor clustering and the normal weight with cardiometabolic risk factor clustering: prevalence and correlates of 2 phenotypes among the US population (NHANES 1999–2004) Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1617–1624. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Radloff LS. The CED-D scale: Self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psych Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA, Brooks JOr, Friedman L, Gratzinger P, Hill RD, et al. Proposed factor structure of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Int Psychogeriatr. 1991;3:23–28. doi: 10.1017/s1041610291000480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G. Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardized assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med. 1992;22:465–486. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700030415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule. Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koster A, Stenholm S, Alley DE, Kim LJ, Simonsick EM, Kanaya AM, et al. Body fat distribution and inflammation among obese older adults with and without metabolic syndrome. Obesity. 2010;18:2354–2361. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pan A, Keum N, Okereke OI, Sun Q, Kivimaki M, Rubin RR, et al. Bidirectional association between depression and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1171–1180. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Renn BN, Feliciano L, Segal DL. The bidirectional relationship of depression and diabetes: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:1239–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Raison CL, Miller AH. The evolutionary significance of depression in pathogen host defense (PATHOS-D) Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:15–37. doi: 10.1038/mp.2012.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Capuron L, Su S, Miller AH, Bremner JD, Goldberg J, Vogt GJ, et al. Depressive symptoms and metabolic syndrome: Is inflammation the underlying link? Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:896–900. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kivimaki M, Shipley MJ, Batty GD, Hamer M, Akbaraly TN, Kumari M, et al. Long-term inflammation increases risk of common mental disorder: a cohort study. Mol Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pan A, Ye X, Franco OH, Li H, Yu Z, Zou S, et al. Insulin resistance and depressive symptoms in middle-aged and elderly Chinese: findings from the Nutrition and Health of Aging Population in China Study. J Affect Disord. 2008;109:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kivimäki M, Tabak AG, Batty GD, Singh-Manoux A, Jokela M, Akbaraly TN, et al. Hyperglycemia, type 2 diabetes, and depressive symptoms: the British Whitehall II study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1867–1869. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Musselman DL, Evans DL, Nemeroff CB. The relationship of depression to cardiovascular disease: epidemiology, biology, and treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:580–592. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bornstein SR, Schuppenies A, Wong ML, Licinio J. Approaching the shared biology of obesity and depression: the stress axis as the locus of gene-environment interactions. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:892–902. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Malhotra S, Nelson EB, Keck PE, Nemeroff CB. Are mood disorders and obesity related? A review for the mental health professional. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:634–651. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jokela M, Hintsanen M, Hakulinen C, Batty GD, Nabi H, Singh-Manoux A, et al. Association of personality with the development and persistence of obesity: a meta-analysis based on individual-participant data. Obes Rev. 2013;14:315–323. doi: 10.1111/obr.12007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.