Abstract

We report the imaging features of a rare sinonasal myxoma situated over the right nasolacrimal duct in a 5-month-old male. We emphasize the importance of including sinonasal myxomas in the list of differential diagnostic possibilities when encountering a nasolacrimal gland mass in an infant, and describe the CT and MRI characteristics of this rare entity.

Introduction

Myxomas of the head and neck in infants are rare, representing fewer than 0.5% of all paranasal sinus and nasal tumors in the pediatric and adult population overall (1). Myxomas are benign, locally invasive mesenchymal neoplasms that are usually found in the mandible and are believed to arise from an odontogenic, osteogenic, or soft-tissue origin (1, 2). Nonodontogenic myxomas arise in the nasolabial region and are termed sinonasal myxomas. These tumors are exceedingly rare, and few well-documented cases have been reported, almost exclusively in children (2). In this case report, we present the CT and MRI findings of a sinonasal myxoma in a 5-month-old boy. Imaging findings, particularly on the diffusion-weighted MRI sequence, improved our ability to accurately differentiate these rare tumors from other lesions that can arise within or around the nasolacrimal duct in an infant. The final diagnosis of sinonasal myxoma ultimately relies on the microscopic analysis of the tissue, which is included in this report. Although rare, the possible diagnosis of sinonasal myxoma should be kept in mind when considering the usual differential diagnosis of an expansile mass over the nasolacrimal duct in an infant, especially when imaging features support this diagnosis.

Case Report

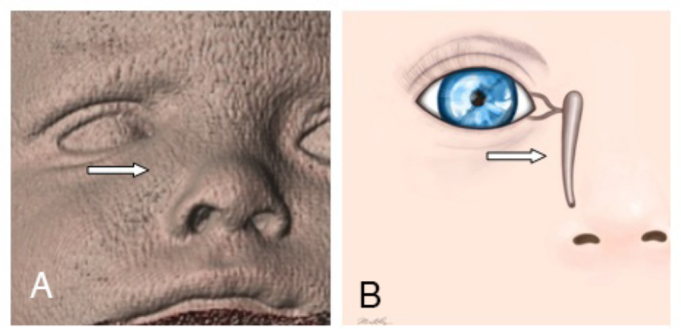

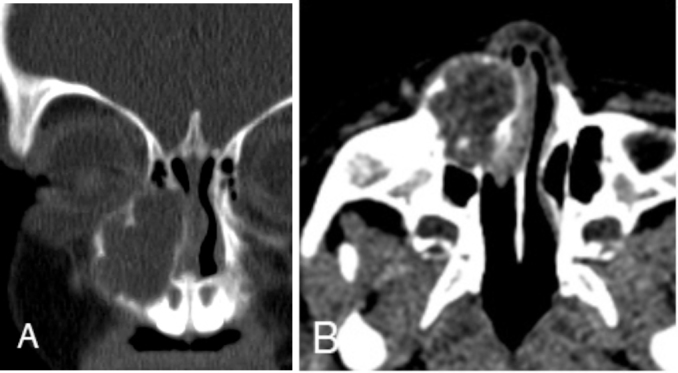

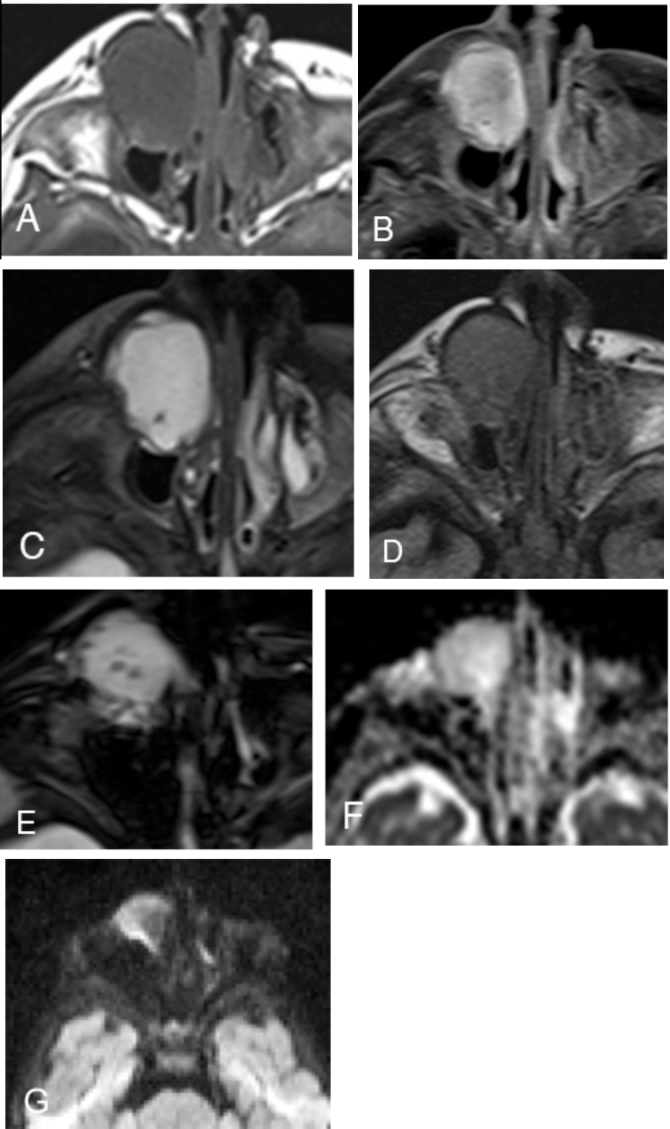

A 5-month-old male infant developed asymptomatic focal right nasolabial swelling over the right nasomaxillary crease that extended over the right cheek (Fig. 1). The mass caused nasolacrimal duct obstruction and epiphora on the right side. After treatment with antibiotics, there was no appreciable change in swelling. A CT scan revealed an expansile, low-attenuation, cystic-appearing mass eroding and protruding into the right nasal cavity and right inferior orbital wall, without bony lysis or intraorbital extension (Figs. 2A-B). A followup MRI examination revealed a well-marginated, T1-hypointense (Fig. 3A), heterogeneously enhancing lesion (3B) that was homogeneously T2-hyperintense (3C). There was incomplete fluid suppression on the T2 FLAIR images (Fig. 3D). Small susceptibility artifacts within the mass were noted on the gradient echo (GRE) sequence, possibly due to calcifications or microhemorrhage (Fig. 3E). Bright signal was present on the ADC map, compatible with facilitated diffusion (Fig. 3F). The general differential diagnosis of an expansile mass situated over the lacrimal gland includes dacryocystocele, dermoid or epidermoid cyst, encephalocele, nasal glioma, hemangioma, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, lymphoma, or sinonasal myxoma.

Fig. 1.

A. 3D surface-rendered image from a CT showing nasolabial swelling over the topography of the right nasolacrimal duct. B. Illustration of the nasolacrimal duct corresponding to the area of swelling. Illustration courtesy of Mia S. Kelly, BA (copyright 2015).

Fig. 2.

Unenhanced CT (coronal and axial) images (A and B) reveal an expansile, lobulated, circumscribed, low-attenuation, soft-tissue mass centered over the right nasomaxillary groove and eroding into the left nasal cavity and inferomedial floor of the right orbit, without bony lysis.

Fig. 3.

A. T1W unenhanced axial image shows homogeneous T1 hypointensity in a well-circumscribed, low-attenuation mass over the right nasolacrimal gland. B. Avid homogeneous enhancement is seen on the post-contrast, fat-saturated T1 view. C. Homogeneous T2 prolongation is seen throughout the lesion except for a punctate focus of low T2 signal posteriorly. D. FLAIR-weighted images show intermediate signal (lack of fluid suppression), which suggests that the lesion is either solid or that it is a cyst containing proteinaceous material. E. GRE axial images reveal several small oval susceptibility artifacts that could represent degraded blood products or mineralization. F. ADC map in axial plane shows high signal within the lesion, indicative of facilitated diffusion.

The presence of enhancement did not support the possibility of a dacryocystocele, encephalocele, epidermoid, dermoid, or nasal glioma (3). There was no T1 shortening to suggest the characteristic fatty component of a dermoid cyst, and there was no restricted diffusion to suggest an epidermoid cyst. There was no bony lysis to support the possibility of a rhabdomyosarcoma or other aggressive neoplasm.

On the ADC map, there was no low signal that would correspond to a highly cellular lesion such as neuroblastoma or lymphoma. Furthermore, bony lysis, characteristically seen in non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the nasal cavity, was not seen (4). The cystic nature of the lesion did not comply with the imaging findings that are characteristic for hemangiomas. There was no connection with the intracranial structures to suggest an encephalocele.

Therefore, based on the CT and MRI findings of an avidly enhancing right nasolacricmal/sinonasal mass causing bony remodeling and increased diffusivity, sinonasal myxoma was favored as the most likely etiology in this case.

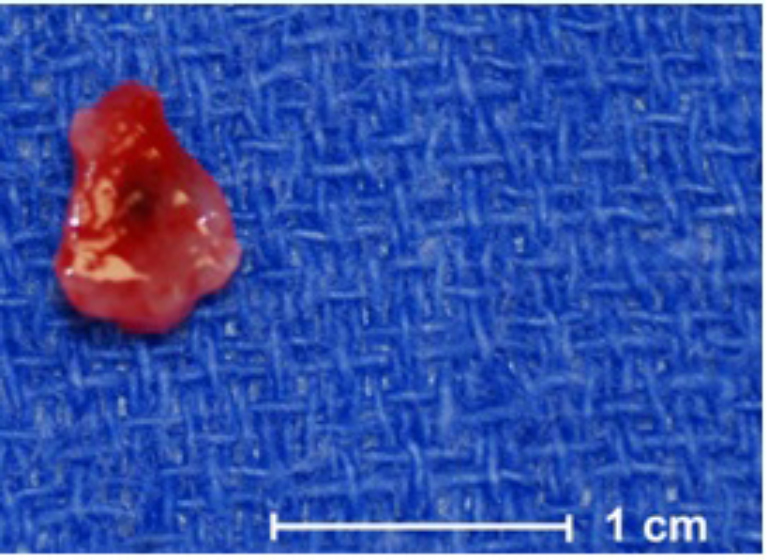

Right endoscopic sinus surgery was performed to open, debulk, and biopsy the right nasolacrimal mass. During surgery, bony expansion without osseous erosion was observed. The mass itself was gelatinous, gray, not vascular, and located medial to and distinct from the right nasolacrimal duct, which was preserved (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Grossly, the biopsy and resection specimen consisted of pink, glistening, gelatinous soft tissue.

Histological analysis revealed loose myxoid tissue interspersed with stellate and spindled fibroblasts, characteristic of a sinonasal myxoma, confirming myxoma (Fig. 5). There was minimal cytoatypia without mitotic activity. Histologically, the tissue did not resemble rhabdomyosarcoma, so vimentin staining was felt to be unnecessary. Immunohistochemical stain for ALK1 was negative in the lesional cells. Cytogenetic analysis performed on a portion of the resection specimen revealed a normal 46, XY male karyotype.

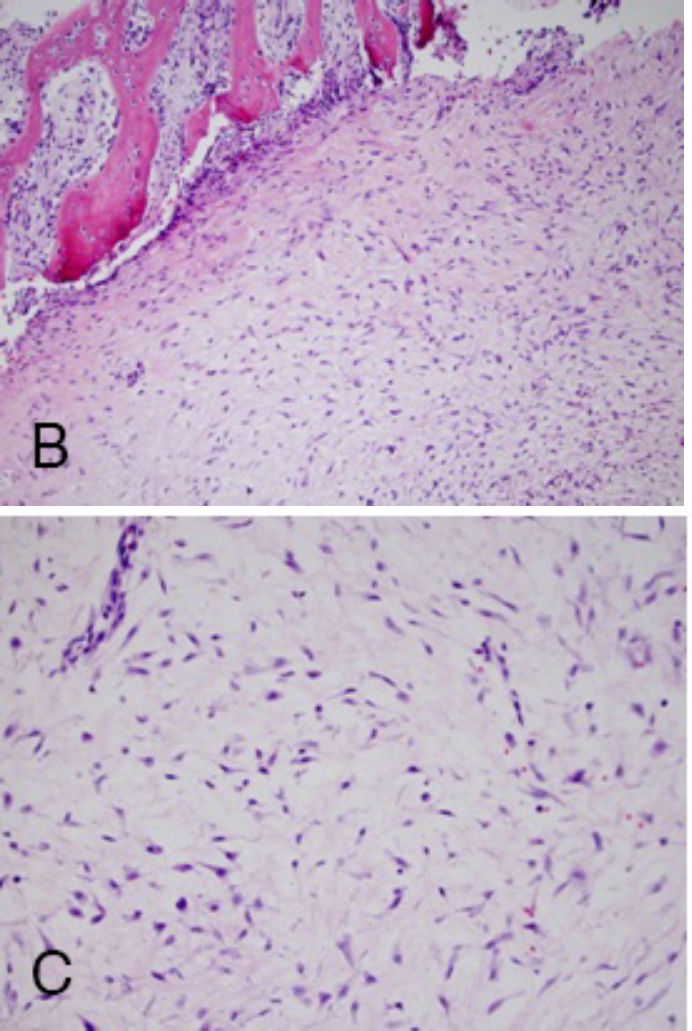

Fig. 5.

A. Histologically, the tumor is composed of loose, myxoid tissue with numerous stellate and spindled fibroblasts. There was minimal cytoatypia, with small bland nuclei and no discernable mitotic activity. There was focal acute hemorrhage, but no necrosis was seen. B. The stroma was superficially infiltrated between bony spicules, eliciting reactive changes including osteoblastic rimming.

Discussion

A previous review of maxillofacial myxomas in infants reported from 1991 to 2010 revealed 14 cases in infants younger than 24 months, all of which spared the mandible. Of the 14 cases, only 8 were purely sinonasal. The age range was 11–20 months, with 9 boys and 6 girls (2). In addition, a case of a sinonasal myxoma was reported in a 12-month-old boy in 2010 involving the nasolacrimal duct itself (5). To our knowledge, the child in our case is the youngest reported infant with a sinonasal myxoma, presenting at 5 months of age. While CT and MRI results have previously been described in a few other similar case reports, we could find no prior description of the MRI diffusion or GRE findings in sinonasal myxomas.

Presurgical diagnosis is important in the management of a sinonasal myxoma, because this type of lesion does not respond to chemotherapy and is poorly responsive to radiotherapy (6). Because of the unencapsulated and infiltrative nature of these tumors, extensive surgery is often required to achieve clear resection margins (7). In one unfortunate reported case, a myxoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses extensively invaded the brain and orbits, causing blindness (8).

Preoperative planning in this case was facilitated by the CT and MR imaging findings. CT showed an expansile erosive mass centered over the right nasolacrimal duct, with bony remodeling but no bony destruction. MRI showed homogeneous avid enhancement, facilitated diffusion, and punctuate susceptibility artifacts on the GRE sequence. Combined, these CT and MRI findings were unique features that appeared to be specific for the suspected sinonasal myxoma. No other type of lesion in this location should, in theory, exhibit these imaging characteristics. Minimally invasive endoscopic biopsy was performed to confirm the diagnosis. Our patient then required two additional surgeries to achieve total tumor resection. He has since been stable without recurrence.

In summary, we have reported the unique MRI findings in a rare case of sinonasal myxoma in a 5-month-old male to emphasize the importance of including this entity in the differential diagnosis when encountering a nasolacrimal lesion. Furthermore, this case demonstrates that presurgical diagnostic accuracy can be improved by including DWI as well as GRE sequences to the MRI protocol when encountering sinonasal lesions. Improved presurgical diagnosis can improve outcome and optimize cosmesis in cases of sinonasal myxomas located in or around the nasolacrimal duct.

References

- 1.Valles-Valles DR, Vera-Torres AM, Rodriguez-Martinez HA, Rodriguez-Reyes AA. Periocular myxoma in a child. Case Reports in Ophthalmological Medicine. 2012:739094. doi: 10.1155/2012/739094. [PubMed] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Safadi A, Fliss DM, Issakov J, Kaplan I. Infantile sinonasal myxoma: A unique variant of maxillofacial myxoma. J. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;59:558–563. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2010.10.007. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabhar R, Resto VA, Robson CD. Nasal glioma and encephalocele: Diagnosis and management. Laryngoscope. 2003 Dec;113(12):2069–2077. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200312000-00003. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chalastras T., Eleteriadou A., Giotakis J. Non-Hodgkins lymphoma of nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. A clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study. ACTA Otorhinolaryngologica Italica. 2007;27:6–9. [PubMed] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Iatrou IA, Theologie-Lygidakis N, Leventis MD, Michail-Strantzia C. Sinonasal myxoma in an infant. J Craniofac Surg. 2010 Sep;21(5):1659–1751. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181ef680a. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.James D.R., Lucas V.S. Maxillary myxoma in a child of 11 months. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 1987;15:42–44. doi: 10.1016/s1010-5182(87)80014-8. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slootweg PJ, Wittkampf ARM. Myxoma of the jaws, an analysis of 15 cases. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 1986;14:46–48. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0503(86)80258-2. [PubMed] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunchaisri N. Myxoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses: Report of a case. J Med Assoc Thai. 2002, Jan;85(1):120–124. [PubMed] abstract only. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]