Abstract

The United States is engaged in ongoing dialogue around mental illness. To assess trends in this national discourse, we studied the volume and content of a random sample of 400 news stories about mental illness from the period 1995–2014. Compared to news stories in the first decade of the study period, those in the second decade were more likely to mention mass shootings by people with mental illnesses. The most frequently mentioned topic across the study period was violence (55 percent overall) divided into categories of interpersonal violence or self-directed (suicide) violence, followed by stories about any type of treatment for mental illness (47 percent). Fewer news stories, only 14 percent, described successful treatment for or recovery from mental illness. The news media’s continued emphasis on interpersonal violence is highly disproportionate to actual rates of violence among those with mental illnesses. Research suggests that this focus may exacerbate social stigma and decrease support for public policies that benefit people with mental illnesses.

The United States is engaged in an ongoing dialogue around mental illness. Over the course of a lifetime, nearly half of all Americans will meet the criteria for a mental health disorder.1 Mental illness is now the leading cause of disability in the United States,2 but only about 40 percent of those affected receive treatment.3 Poor treatment rates are a function of multiple factors, including the historically separate financing and delivery of mental health services in the United States, provider shortages, and stigma.4–6 The past two decades have witnessed growing national awareness and discussion of these issues,7 as well as debate of policy options to close the mental health treatment gap.4,8 At the same time, considerable national dialogue has been devoted to the role of mental illness in interpersonal violence, a topic prompted in recent years by a series of high-profile mass shootings in which the perpetrator had a documented or purported serious mental illness, such as schizophrenia.9,10 Rising rates of suicide, particularly among members and veterans of the US military; the overrepresentation of people with mental illness in the criminal justice system; and the development of new therapies have also been a recent focus of the national discourse over mental illness.11–13

An established method for assessing the national dialogue around societal issues such as mental illness is analysis of news media coverage, which is viewed as both reflecting and shaping public discourse.14,15 News coverage reflects public discourse by reporting on the views and positions of the policy makers, advocacy groups, researchers, members of the public, and others engaged in issue debates, often directly quoting the key players.15 News coverage shapes public discourse and attitudes about societal issues in two main ways: agenda setting and issue framing.14,16 By focusing news coverage on certain topics, the news media influence which issues audiences deem important and in need of public policy response (agenda setting).14 By highlighting certain aspects of issues, the news media can influence public opinion about and preferred solutions to societal problems (known as “issue framing”).14

Descriptive studies of US news media content from the 1980s and 1990s showed that news stories about mental illness emphasized interpersonal violence.17,18 Most recently, Otto Wahl and colleagues examined news stories about mental illness that were published in six high-circulation US newspapers in a single year, 1999, and found that dangerousness was the most common theme in coverage, with more than a quarter of news stories involving accounts of violent criminal activity by people with mental illnesses.17 Wahl and his colleagues’ findings are consistent with studies of news coverage of mental illness in other nations, including Canada,19 the United Kingdom,20 New Zealand,21 and Spain.22 Emphasis on interpersonal violence in news coverage of mental illness is concerning given that most people with mental illnesses are never violent and only about 4 percent of interpersonal violence in the United States is attributable to mental illness.23 News coverage linking interpersonal violence to mental illness has been shown to exacerbate already high levels of social stigma toward those with mental illnesses.24 This emphasis on violence instead of other mental illness–related topics might contribute to a societal focus on enacting public safety–oriented policies, such as mandatory treatment and firearm restrictions, at the expense of public health–oriented policies designed to foster recovery.9,25,26

No prior US studies have either examined the content of recent news coverage of mental illness or assessed trends in coverage over time. To fill these gaps, in our study we analyzed the volume and content of news coverage of mental illness over the past two decades, from 1995 to 2014. In addition to examining the topics and policies discussed in news stories about mental illness over this period, we assessed three types of news media messages shown in prior research to influence public attitudes about societal issues and support for policy: mentions of specific causes of mental illness (for example, neurobiological, trauma, and family-related causes), mentions of the consequences of mental illness (for example, criminal justice system involvement, stigma, and premature mortality), and individual depictions of people with mental illnesses (for example, a person with mental illness involved in the criminal justice system, undergoing successful treatment, or experiencing homelessness). Research shows that news media mentions of the causes and consequences of societal problems can influence audiences’ perceptions of the importance of an issue, attributions of responsibility for solving the problem, and endorsement of certain types of policy options that target the causes and address the consequences emphasized in the messages.27–30 Public attitudes about groups of people affected by societal problems—in this case, mental illness—are influenced by news media depictions of specific individuals who exemplify the problem in question, even if the individual depicted is not representative of the larger group.31

Study Data And Methods

APPROACH AND STUDY SAMPLE

We conducted a quantitative content analysis of a random sample of 400 US news stories about mental illness published or aired by high-circulation and high-viewership print and television news sources during 1995–2014.We used the LexisNexis and ProQuest online news archives to identify news stories focused on mental illness. News sources included three of the highest-circulation national newspapers in the United States during the study period (USA Today, Wall Street Journal, and Washington Post); one of the highest-circulation newspapers in each of the four US census regions (New York Times, Chicago Tribune, Atlanta Journal Constitution, and Los Angeles Times); evening news programs on three national television networks (ABC, NBC, and CBS); and all CNN news programs. All of the individual news sources selected were the highest-circulation or -viewership news source available for the twenty-year study period in the LexisNexis or ProQuest online archives.

NEWS COVERAGE SELECTION

We searched the headlines of print news stories and television transcripts (LexisNexis and ProQuest include headlines for television transcripts, which, like newspaper headlines, summarize the topic of the news story) for news stories between 1995 and 2014 using the following search terms: “mental illness” or “mental health” or “mental” or “psych” or “depression” or “schizo” or “bipolar” or “anxiety” or “ptsd” or “adhd” or “attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder” or “attention deficit disorder” or “post-traumatic stress disorder” or “suicide.” The search returned 22,730 news stories. We selected a simple random sample of stories, excluding those not focused on mental illness (news stories were included if the majority of the story described any topic related to clinical mental illnesses; news stories about more general mental well-being topics, such as stress relief, were excluded), until we achieved an analytic sample of 400 randomly selected news stories. News stories and editorials with 100 or fewer words were excluded, as were letters to the editor, book reviews, and obituaries. The final study sample included 362 print news stories, 13 print opinion pieces, and 25 television news stories.

More than half of news stories mentioned some type of violence related to mental illness.

MEASURES

To assess the content of news stories about mental illness, we developed a sixty-nine-item structured coding instrument (see Supplemental Exhibit 1 in the online Appendix)32 that captured items in five domains: specific topics in news coverage about mental illness, causes of mental illness, consequences of mental illness, individual depictions of people with mental illnesses, and public policies related to mental illness. We measured mentions of fifteen specific topics in news coverage including interpersonal violence, suicide, and treatment. Six specific causes of mental illness were measured, including stressful life events and genetics or biology. Likewise, six specific consequences of mental illness were coded, including criminal justice involvement and premature mortality. Nine different types of individual depictions were captured, including people with mental illnesses committing interpersonal violence or experiencing discrimination. Finally, we coded eleven specific public policies related to mental illness, including policies to expand inpatient treatment and community-based services.

All measures were dichotomous items. Two of this article’s authors (Alene Kennedy-Hendricks and Seema Choksy) pilot-tested the instrument on a small subset of twenty articles and refined it based on pilot results. Once the instrument was finalized, a random sample of 25 percent (n = 100) of news stories was double-coded by the same two authors to assess interrater reliability for each dichotomous yes-no item in the coding instrument. All items met conventional standards for adequate reliability, with kappa values of 0.69 or higher (see the Appendix).32 Data were collected and analyzed from August to December 2015.

DATA ANALYSIS

We calculated the proportion of news stories mentioning each measure. To assess whether news coverage of mental illness changed over time, we used chi-square tests to compare the proportion of news stories mentioning a given measure in the first decade of the study period (1995–2004) versus the second decade (2005–14). We ran logistic regression models, controlling for news story word count and adjusting standard errors for lack of independence within news sources, to examine correlations between news media mentions of specific mental illness topics, causes, and consequences and mentions of mental illness treatment policies. We calculated predicted probabilities to illustrate the results of these models. We also conducted sensitivity analyses using chi-square tests to examine differences across five-year periods (1995–99 versus 2000–04 versus 2005–09 versus 2010–14).

LIMITATIONS

Our results should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. Our sample did not include the local television, blogs, and other online sources through which many Americans now access at least some of their news. Unfortunately, given that our study period spans twenty years, systematically analyzing such news sources was not feasible. Our exclusion of local television news sources is also an important limitation since a majority of Americans note local news as their primary news source,33 and it is not clear whether local news would follow the same coverage patterns that we observed in the national and regional news sources in our sample.

Second, assessing how news media coverage of mental illness was associated with public attitudes during our study period was outside the scope of this study.

Third, because of our sampling approach, the majority of the study sample (94 percent) consisted of print news stories, which means that we were unable to test for systematic differences in coverage by news medium.

Finally, our analysis did not permit us to explain trends in news coverage of mental illness, which might be driven by competing issues in the news cycle or the shifting landscape of news coverage over time.

Study Results

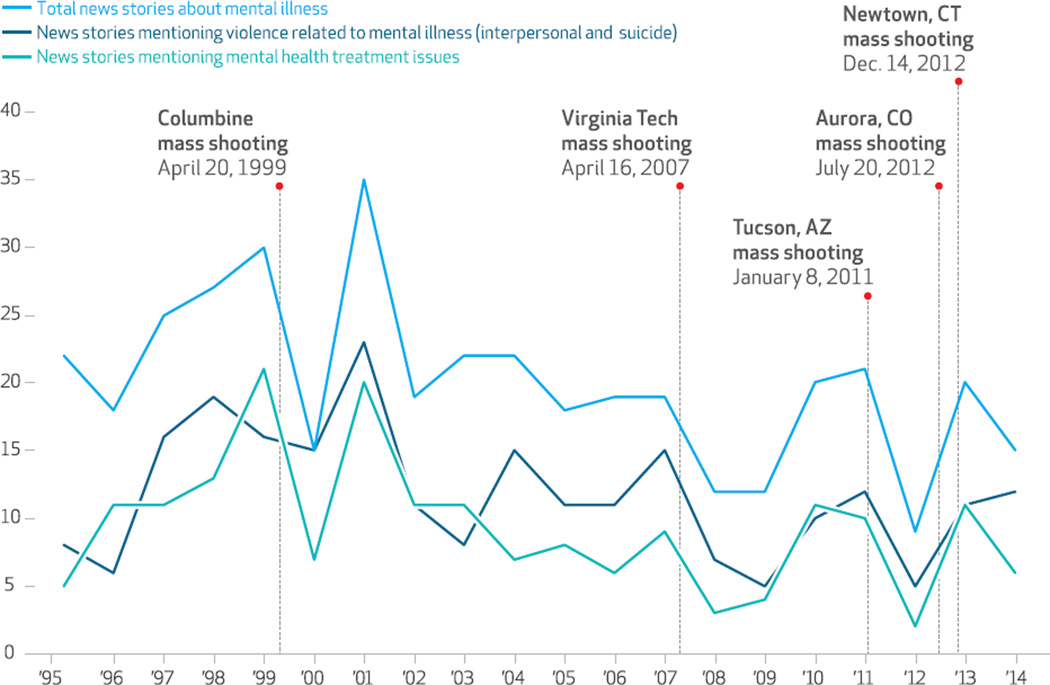

The volume of news coverage about mental illness trended downward over time (Exhibit 1). The two most frequently mentioned specific topics in news coverage about mental illness were violence—including both interpersonal violence and suicide—and mental health treatment issues.

Exhibit 1.

Volume of US news coverage focused on mental illnesses overall, by mention of violence, and by mention of treatment

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of news media data, 1995–2014. NOTE N = 400 news stories.

Across the two decades of news coverage examined, there were no differences in the issues mentioned in news stories about mental illness (Exhibit 2). Overall, 55 percent of news stories mentioned violence related to mental illness, either interpersonal violence (38 percent) or suicide (29 percent), and nearly half mentioned treatment (47 percent). Of the latter, issues surrounding access to, funding for, and quality of treatment for mental illness were most frequently mentioned (26 percent, 19 percent, and 16 percent, respectively). Fourteen percent of news stories mentioned successful treatment for or recovery from mental illness.

Exhibit 2.

Specific topics mentioned in news coverage about mental illness, 1995–2014

| 1995–2014 (N = 400) |

1995–2004 (n = 235) |

2005–14 (n = 165) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Any type of violence related to mental illness | 219 | 55 | 127 | 54 | 92 | 56 |

| Interpersonal violence related to mental illness | 152 | 38 | 92 | 39 | 60 | 36 |

| Self-directed violence (suicide) related to mental illness | 114 | 29 | 66 | 28 | 48 | 29 |

| Any type of treatment of mental illness | 187 | 47 | 117 | 49 | 70 | 42 |

| Access to treatment for mental illness | 102 | 26 | 63 | 27 | 39 | 24 |

| Funding for treatment for mental illness | 76 | 19 | 48 | 20 | 28 | 17 |

| Quality of treatment for mental illness | 65 | 16 | 41 | 17 | 24 | 15 |

| Description of successful treatment for or recovery from mental illness | 55 | 14 | 33 | 14 | 22 | 13 |

| Ineffective or unsuccessful treatment | 26 | 7 | 13 | 6 | 13 | 8 |

| Development of a new medication or treatment for mental illness | 17 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 9 | 5 |

| Iatrogenic effects of treatment (for example, negative side effects) | 11 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 2 |

| Separation of treatment for mental illness and general medical care | 9 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Insurance coverage of treatment for mental illness | 49 | 12 | 33 | 14 | 16 | 10 |

| Neurobiological basis of mental illness | 39 | 10 | 21 | 9 | 18 | 11 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of news media data, 1995–2014. NOTE No results were significant (p < 0.05) after the use of chi-square tests to compare the proportion of news stories mentioning a given measure in the first decade of the study period (1995–2004) versus the second decade (2005–14).

News coverage of mental illness and interpersonal violence focused on gun violence and mass shootings. In the subset of news stories about mental illness that mentioned interpersonal violence (n = 152), nearly three-quarters depicted a specific violent event committed by a person with or purported to have a mental illness (Exhibit 3). The most frequent type of events depicted were gun violence events generally and, more specifically, family violence events, mass shootings, and school shootings. News media descriptions of mass shootings by individuals with mental illnesses increased over the course of the study period, from 9 percent of all news stories in 1994–2004 to 22 percent in 2005–14 (p < 0.05). The proportion of newspaper stories about interpersonal violence related to mental illness that appeared on the front page increased from 1 percent in the first decade of the study period to 18 percent in the second decade (p < 0.001).

Exhibit 3.

Content and type of news stories about mental illness and interpersonal violence, 1995–2014

| 1995–2014 (N = 152) |

1995–2004 (n = 92) |

2005–14 (n = 60) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| NEWS STORY MENTIONED: | ||||||

| Depiction of specific violent event committed by a person with mental illness | 113 | 74 | 68 | 74 | 45 | 75 |

| Gun violence event | 41 | 27 | 22 | 24 | 19 | 32 |

| Mass shooting event | 21 | 14 | 8 | 9 | 13 | 22** |

| School shooting event | 13 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 12 |

| Family violence event | 22 | 14 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 17 |

| STATEMENTS ABOUT MENTAL ILLNESSES AND INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE | ||||||

| Mental illness increases the risk of interpersonal violence | 57 | 38 | 34 | 37 | 23 | 38 |

| Most people with mental illnesses are not violent toward others | 12 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 3 | 5 |

| It is difficult to predict interpersonal violence in people with mental illnesses | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| SPECIFIC DIAGNOSES MENTIONED IN THE CONTEXT OF INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE | ||||||

| Schizophrenia | 26 | 17 | 14 | 15 | 12 | 20 |

| Depression | 16 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 4 | 7 |

| Bipolar disorder | 4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Psychotic symptoms mentioned in the context of interpersonal violence | 25 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 8 | 13 |

| RISK FACTORS FOR VIOLENCE | ||||||

| Drug use | 8 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 2 | 3 |

| Stressful life event precipitating violence | 8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Alcohol use | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Abuse or trauma | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| TYPE OF NEWS STORY | ||||||

| Print news | 129 | 85 | 77 | 84 | 52 | 87 |

| Front page | 12 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 18**** |

| Print opinion | 8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Television news | 18 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 5 | 8 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of news media data, 1995–2014. NOTE Significance was determined by the use of chi-square tests to compare the proportion of news stories mentioning a given measure in the first decade of the study period (1995–2004) versus the second decade (2005–14).

p < 0.05

p < 0.001

There were very few differences in news media mentions of the causes, consequences, and individual depictions of mental illness in the first versus second decade of the study period (Exhibit 4). The most frequently mentioned causes of mental illness over the entire study period were stressful life events (17 percent) and genetics or biology (14 percent). The most frequently mentioned consequences of mental illness overall were criminal justice involvement (29 percent) and stigma or discrimination (25 percent). The most frequently occurring individual depiction was of a person with mental illness committing interpersonal violence (28 percent). Only 7 percent of news stories over the entire study period included a depiction of successful treatment or recovery by a person with mental illness.

Exhibit 4.

Causes, consequences, and individual depictions of mental illness in US news coverage, 1995–2014

| 1995–2014 (N = 400) |

1995–2004 (n = 235) |

2005–14 (n = 165) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| News story mentioned: | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Any cause of mental illness | 140 | 35 | 71 | 30 | 69 | 42 |

| Stressful life event | 67 | 17 | 37 | 16 | 30 | 18 |

| Genetics or biology | 57 | 14 | 37 | 16 | 20 | 12 |

| Military or war involvement | 26 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 21 | 13**** |

| Trauma or abuse | 25 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 14 | 9 |

| Family environment or upbringing | 12 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Any consequence of mental illness | 223 | 56 | 131 | 56 | 92 | 56 |

| Criminal justice system involvement | 115 | 29 | 75 | 32 | 40 | 24 |

| Stigma or discrimination | 99 | 25 | 53 | 23 | 46 | 28 |

| Employment problems | 53 | 13 | 27 | 11 | 26 | 16 |

| Housing problems | 44 | 11 | 29 | 12 | 15 | 9 |

| Premature mortality | 6 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Any individual depiction of a person with mental illness | 187 | 47 | 108 | 46 | 79 | 47 |

| Depiction of interpersonal violence by a person with mental illness | 113 | 28 | 68 | 29 | 45 | 27 |

| Depiction of criminal justice system involvement by a person with mental illness | 82 | 21 | 55 | 23 | 27 | 16 |

| Depiction of suicide by a person with mental illness | 61 | 15 | 36 | 15 | 25 | 15 |

| Depiction of a person with mental illness experiencing unemployment | 32 | 8 | 13 | 6 | 19 | 12*** |

| Depiction of successful treatment or recovery by a person with mental illness | 29 | 7 | 18 | 8 | 11 | 7 |

| Depiction of unsuccessful treatment by a person with mental illness | 24 | 6 | 12 | 5 | 12 | 7 |

| Depiction of discrimination experienced by a person with mental illness | 24 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 11 | 7 |

| Depiction of a person with mental illness experiencing homelessness | 16 | 4 | 9 | 4 | 7 | 4 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of news media data, 1995–2014. NOTE Significance was determined by the use of chi-square tests to compare the proportion of news stories mentioning a given measure in the first decade of the study period (1995–2004) versus the second decade (2005–14).

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Over the twenty-year period, about a quarter of all news stories about mental illness mentioned a specific public policy issue (24 percent) (Exhibit 5). Policies related to the treatment of mental illness were the most frequently mentioned category of policy (14 percent of news stories).

Exhibit 5.

US news coverage of mental health policy issues, 1995–2014

| 1995–2014 (N = 400) |

1995–2004 (n = 235) |

2005–14 (n = 165) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| News story mentioned: | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % |

| Any mental health policy | 95 | 24 | 55 | 23 | 40 | 24 |

| Treatment-related policies | 55 | 14 | 32 | 14 | 23 | 14 |

| Policies to expand community-based outpatient mental health treatment | 40 | 10 | 24 | 10 | 16 | 10 |

| Policies to expand inpatient mental health treatment | 13 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Mandatory treatment policiesa | 12 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

| ACA provisions related to mental health treatment | 1 | <1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| US military or veteran mental health screening and treatment policies | 18 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 14 | 8 |

| Mental health insurance parity policiesb | 15 | 4 | 14 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| Criminal justice diversion policiesc | 13 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Mental illness–focused firearm policies | 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Disability policies related to mental illness | 4 | 1 | 1 | <1 | 3 | 2 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of news media data, 1995–2014. NOTES No results were significant (p < 0.05) after the use of chi-square tests to compare the proportion of news stories mentioning a given measure in the first decade of the study period (1995–2004) versus the second decade (2005–14). ACA is Affordable Care Act.

For example, inpatient commitment or assisted outpatient treatment policies.

For example, state insurance parity laws or the federal Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008.

For example, pretrial diversion policies or mental health court policies.

News media mentions of treatment for mental illness, interpersonal violence, and criminal justice system involvement were positively correlated with mentions of mental health treatment policies (see Supplemental Exhibits 2–6 in the Appendix).32 Stories that mentioned mental health treatment topics had higher predicted probabilities of also mentioning any treatment-related public policies, compared to other news stories (27 percent versus 2 percent). These included policies to expand community-based outpatient services (19 percent versus 5 percent) and policies to expand inpatient services (7 percent versus 1 percent). News stories mentioning interpersonal violence related to mental illness had higher predicted probabilities of mentioning any treatment-related policies (22 percent versus 8 percent), policies to expand inpatient treatment (7 percent versus 1 percent), and mandatory treatment policies (9 percent versus 3 percent) than stories that did not mention interpersonal violence. Stories that mentioned criminal justice involvement as a consequence of mental illness had higher predicted probabilities of also mentioning any treatment-related policy (23 percent versus 10 percent), compared to other news stories. These included policies to expand community-based outpatient services (14 percent versus 8 percent), policies to expand inpatient mental health services (8 percent versus 1 percent), and mandatory treatment policies (6 percent versus 2 percent). News stories mentioning military or war involvement were more likely than other news stories to also mention policies to improve mental health screening and treatment of US military and veteran populations (62 percent versus 1 percent).

Coverage has continued to emphasize interpersonal violence in a way that is highly disproportionate to actual rates of such violence.

Sensitivity analyses showed no differences in trends in the content of news coverage about mental illness over time when time was measured in five-year periods versus decades (results not shown; available from the authors on request).

Discussion

The volume of US print and television news coverage of mental illness trended downward from 1995 through 2014, aligning with the secular trend in the downsizing of newspapers. This downsizing trend had a disproportionate effect on the volume of science reporting, which might have contributed to the decreasing volume of news coverage of mental illness observed in this study.34 The content of news stories about mental illness changed very little during those twenty years. Overall, the most frequently mentioned topics pertained to interpersonal violence, suicide, and treatment of mental illness. Policies to improve or expand treatment were also the most frequently mentioned category of mental health policies, although such policies were mentioned in only 14 percent of stories. Criminal justice involvement was the most frequently mentioned consequence of mental illness, and when the news media portrayed a specific individual with mental illness, that individual was most frequently depicted as having committed an act of interpersonal violence.

More than half of news stories mentioned some type of violence related to mental illness. News stories were more likely to mention interpersonal violence than suicide, despite the fact that research indicates that suicide is much more directly related to mental illness than interpersonal violence.23 While the proportion of news stories mentioning interpersonal violence did not change over the two ten-year periods studied, these news stories were more likely to appear on the front page of newspapers in the second decade of the study period, which suggests that the prominence of this issue relative to other topics reported by the news media has increased. Our finding that the share of news stories mentioning mass shootings increased substantially in the most recent decade was consistent with another recently published study showing that the majority of US news coverage of mental illness and gun violence from 1997 to 2012 focused on mass shootings.10 These findings raise troubling implications for social stigma toward people with mental illnesses in the United States. Multiple studies have demonstrated a positive association between news coverage of violence by people with mental illnesses and stigma,24,35,36 and the news media’s emphasis on interpersonal violence over the two decades we studied mirrors unchanging levels of stigma toward people with mental illnesses in the United States.7,37 A 2013 experimental study found that exposure to a news story describing a mass shooting by an individual with a history of mental illness significantly exacerbated already high levels of social stigma toward people with mental illnesses.24

In contrast, a recent study found that depictions of people with mental illnesses receiving successful treatment and living productive lives in the community decreased levels of social stigma.38 However, we found that only 14 percent of news stories included any mention of the possibility of successful treatment or recovery, and only 7 percent included the type of individual depiction of a person in successful treatment shown to be effective at reducing stigma.38 Social stigma toward people with mental illnesses, which was mentioned as a consequence of mental illness in a quarter of all news stories, is important for several reasons. Social stigma and related discriminatory behavior is associated with low rates of mental health treatment seeking and adherence,39 and with a host of negative outcomes such as homelessness, unemployment, and criminal justice involvement.40 Furthermore, high social stigma is associated with lower levels of public support for policies that benefit people with mental illnesses, such as insurance parity and expanded government funding for treatment.41

Interestingly, news stories about interpersonal violence more frequently mentioned mental health treatment policies than other news stories did. While effective treatment can prevent the small subset of interpersonal violence resulting directly from mental illness—for example, violent actions prompted by psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations or delusions—most interpersonal violence in US society is not caused by mental illness and therefore not preventable by treatment.9,23 Nonetheless, in recent years many advocacy groups and policy makers have argued for improving the mental health treatment system as a strategy for addressing high rates of gun violence generally, and mass shootings specifically, in the United States.9,26,42 Research suggests that this policy approach, advanced partly in an attempt to shift public attention and political momentum away from strengthening US gun laws, will not meaningfully address gun violence in America and might reinforce the link between mental illness and violence in the public psyche.23,42,43

Our study period coincided with US military involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan, which likely influenced news media content in several domains. News stories that mentioned military or war involvement as a cause of mental illness were more likely than other news stories to also mention policies to improve mental health screening and treatment for members and veterans of the US military. Despite the fact that suicide disproportionately affects these groups, news stories about suicide were no more or less likely than other stories to mention policies in this category.

Conclusion

News media coverage of mental illness changed very little during 1995–2014. Coverage has continued to emphasize interpersonal violence in a way that is highly disproportionate to actual rates of such violence among the US population with mental illness. Initiatives to educate reporters and the opinion leaders they use as sources regarding the relationship between mental illness and interpersonal violence are needed, as are efforts to increase news media depictions of successful treatment for and recovery from mental illness, which have the potential to reduce harmful social stigma toward this population.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Emma E. McGinty, Email: bmcginty@jhu.edu, Department of Health Policy and Management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and co–deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Mental Health and Addiction Policy Research, in Baltimore, Maryland.

Alene Kennedy-Hendricks, Department of Health Policy and Management, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Seema Choksy, Department of Internal Medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

Colleen L. Barry, Department of Health Policy and Management, with a joint appointment in the Department of Mental Health, both at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and is codirector of the Johns Hopkins Center for Mental Health and Addiction Policy Research.

NOTES

- 1.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Institute of Mental Health. Bethesda (MD): NIMH; 2015. [cited 2016 Apr 26]. U.S. leading categories of diseases/disorders [Internet] Available from: http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/disability/us-leading-categories-of-diseases-disorders.shtml. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang PS, Demler O, Kessler RC. Adequacy of treatment for serious mental illness in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(1):92–98. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.1.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frank RG, Glied SA. Better but not well: mental health policy in the United States since 1950. Baltimore (MD): Johns Hopkins University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunningham PJ. Beyond parity: primary care physicians’ perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 2009;28(3):w490–w501. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hogan MF. The President’s New Freedom Commission: recommendations to transform mental health care in America. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(11):1467–1474. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.11.1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, Medina TR, Phelan JC, Link BG. “A disease like any other”? A decade of change in public reactions to schizophrenia, depression, and alcohol dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(11):1321–1330. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barry CL, Huskamp HA. Moving beyond parity—mental health and addiction care under the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):973–975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1108649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glied S, Frank RG. Mental illness and violence: lessons from the evidence. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(2):e5–e6. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGinty EE, Webster DW, Jarlenski M, Barry CL. News media framing of serious mental illness and gun violence in the United States, 1997–2012. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):406–413. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuehn BM. Soldier suicide rates continue to rise: military, scientists work to stem the tide. JAMA. 2009;301(11):1111–1113. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.LeardMann CA, Powell TM, Smith TC, Bell MR, Smith B, Boyko EJ, et al. Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former US military personnel. JAMA. 2013;310(5):496–506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.65164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Steadman HJ, Osher FC, Robbins PC, Case B, Samuels S. Prevalence of serious mental illness among jail inmates. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(6):761–765. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.6.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scheufele DA, Tewksbury D. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: the evolution of three media effects models. J Commun. 2007;57(1):9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graber DA, Dunaway J. Mass media and American politics. Thousand Oaks (CA): CQ Press; 2014. pp. 272–308. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCombs M. Agenda setting function of mass media. Public Relat Rev. 1977;3(4):89–95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wahl OF, Wood A, Richards R. Newspaper coverage of mental illness: is it changing? Psychiatr Rehabil Skills. 2002;6(1):9–31. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wahl OF. Mass media images of mental illness: a review of the literature. J Comm Psychol. 1992;20(4):343–352. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Day DM, Page S. Portrayal of mental illness in Canadian newspapers. Can J Psychiatry. 1986;31(9):813–817. doi: 10.1177/070674378603100904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Philo G, Secker J, Platt S, Henderson L, McLaughlin G, Burnside J. The impact of the mass media on public images of mental illness: media content and audience belief. Health Educ J. 1994;53(3):271–281. [Google Scholar]

- 21.New Zealand Mental Health Commission. Discrminating times? A resurvey of New Zealand print media reporting on mental health [Internet] Wellington: Mental Health Commission; 2005. Jun, [cited 2016 May 4]. Available from: http://www.hdc.org.nz/media/199605/discriminating%20times.%20a%20re-survey%20of%20nz%20print%20media%20reporting%20on%20mental%20health%20june%2005.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aragonès E, López-Muntaner J, Ceruelo S, Basora J. Reinforcing stigmatization: coverage of mental illness in Spanish newspapers. J Health Commun. 2014;19(11):1248–1258. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.872726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Swanson JW, McGinty EE, Fazel S, Mays VM. Mental illness and reduction of gun violence and suicide: bringing epidemiologic research to policy. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(5):366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGinty EE, Webster DW, Barry CL. Effects of news media messages about mass shootings on attitudes toward persons with serious mental illness and public support for gun control policies. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(5):494–501. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13010014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider A, Ingram H. Social construction of target populations: implications for politics and policy. Am Polit Sci Rev. 1993;87(2):334–347. [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGinty EE, Webster DW, Barry CL. Gun policy and serious mental illness: priorities for future research and policy. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(1):50–58. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barry CL, Brescoll VL, Brownell KD, Schlesinger M. Obesity metaphors: how beliefs about the causes of obesity affect support for public policy. Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):7–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00546.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Iyengar S. Framing responsibility for political issues. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 1996;546(1):59–70. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kingdon JW. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. Second. Washington (DC): Pearson; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gollust SE, Niederdeppe J, Barry CL. Framing the consequences of childhood obesity to increase public support for obesity prevention policy. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(11):e96–e102. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zillman D, Brosius H-B. Exemplification in communication: the influence of case reports on the perception of issues. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 33.Pew Research Center’s Journalism Project. State of the news media 2014 [Internet] Washington (DC): Pew Research Center; 2014. Mar 26, [cited 2016 Apr 26]. Available from: http://www.journalism.org/packages/state-of-the-news-media-2014/ [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pew Research Center. The changing newsroom: what is being gained and what is being lost in America’s daily newspapers? [Internet] Washington (DC): The Center; 2008. Jul 21, [cited 2016 Apr 26]. Available from: http://www.journalism.org/2008/07/21/the-changing-newsroom-2/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thornton JA, Wahl OF. Impact of a newspaper article on attitudes toward mental illness. J Comm Psych. 1996;24(1):17–25. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H. The effect of violent attacks by schizophrenic persons on the attitude of the public towards the mentally ill. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(12):1721–1728. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00065-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phelan JC, Link BG, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public conceptions of mental illness in 1950 and 1996: what is mental illness and is it to be feared? J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(2):188–207. [Google Scholar]

- 38.McGinty EE, Goldman HH, Pescosolido B, Barry CL. Portraying mental illness and drug addiction as treatable health conditions: effects of a randomized experiment on stigma and discrimination. Soc Sci Med. 2015;126:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pescosolido BA, Medina TR, Martin JK, Long JS. The “backbone” of stigma: identifying the global core of public prejudice associated with mental illness. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):853–860. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barry CL, McGinty EE. Stigma and public support for parity and government spending on mental health: a 2013 national opinion survey. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(10):1265–1268. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Metzl JM, MacLeish KT. Mental illness, mass shootings, and the politics of American firearms. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):240–249. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubin R. Mental health reform will not reduce US gun violence, experts say. JAMA. 2016;315(2):119–121. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.